Published online Aug 28, 2025. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v17.i8.107463

Revised: June 10, 2025

Accepted: August 6, 2025

Published online: August 28, 2025

Processing time: 157 Days and 11.5 Hours

Diverticulitis is an infection of the diverticular sacs protruding from the intestinal wall. It typically presents as elevated inflammatory markers and left lower quadrant abdominal pain. Although clinical symptoms and biomarkers are es

Core Tip: Abdominal pain is one of the most common complaints leading to emergency department visits. A significant proportion of patients presenting with elevated inflammatory markers are diagnosed with diverticular disease, including diverticulitis and its complications. A standardized classification system and computed tomography imaging are crucial for ensuring accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment. This review provides a comprehensive overview of the imaging findings, classification, and complications of diverticulitis.

- Citation: Simsar M, Yuruk YY, Sahin O, Sahin H. Radiological insights into diverticulitis: Clinical manifestations, complications, and differential diagnosis. World J Radiol 2025; 17(8): 107463

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v17/i8/107463.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v17.i8.107463

Intestinal diverticula are pouches involving the mucosa, submucosa, and muscular layers of the intestinal wall. Pseudodiverticula are associated with advanced age and formed by the protrusion of the mucosa and submucosa through the circular muscle layer of the colon[1]. The term diverticulosis refers to asymptomatic pseudodiverticula, while diver

The annual incidence of colonic diverticulitis in the United States is 209 cases per 100000 individuals[3]. Although the pathophysiology of diverticular disease has not been clearly defined, factors such as fiber deficiency and microbiota are thought to play a role in the onset of the disease. The fiber content in the diet influences the size and consistency of stool. Without enough fiber intraluminal pressure can increase causing the herniation of the colonic mucosa through weak areas in the muscular layer. Other factors, such as altered neuromuscular activity and genetics, also contribute to the development of diverticular disease[4]. The retraction and entrapment of submucosal blood vessels within the diverticula combined with fecal obstruction of the diverticular orifice promote bacterial overgrowth and prolonged exposure within the lumen. These events initiate ischemic processes that heighten the risk of inflammation, thereby leading to the onset of diverticulitis[5].

The clinical recognition of acute colonic diverticulitis (ACD) can be challenging because left lower quadrant pain, leukocytosis, and fever are common symptoms. Radiology is crucial in differentiating diverticulitis from other diseases with similar findings and guiding treatment decisions, including conservative management, percutaneous drainage, and surgical intervention[6].

A structured literature review was conducted using the PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases between January and June 2025. The following MeSH terms and keywords were used: “Diverticulitis”, “complicated diverticulitis”, “Hinchey classification”, “Sartelli classification”, “Segmental colitis associated with diverticulosis”, “colorectal cancer”, “deep learning”, and “computed tomography”. Studies published in English over the past decade were included to reflect contemporary clinical practice and technological advancements. All computed tomography (CT) images used in this review were retrospectively retrieved in anonymized form from the institutional Picture Archiving and Communication System with approval from the local institutional review board. No identifiable patient information was included.

Diverticular disease is investigated through radiological imaging and endoscopic procedures. Although endoscopy can provide valuable diagnostic information, its use is limited in cases of acute diverticulitis due to the risk of perforation and bleeding[7]. At this point the role of radiology becomes crucial. Historically, barium enema studies were conducted. Currently, ultrasound (US) and CT are preferred due to their ability to detect intraluminal and extracolonic pathologies such as abscess formation[8].

US is typically the first-line imaging modality. It is a practical modality in situations where radiation exposure should be avoided, such as during pregnancy and in patients who are lean. However, its diagnostic accuracy is dependent on the experience of the operator, and its effectiveness is reduced when evaluating deep abdominal regions in patients with obesity[7,9].

According to various meta-analyses, research studies, and systematic reviews, there are no statistically significant differences in the sensitivity and specificity of US and CT. However, CT demonstrates clear superiority in identifying complicated cases and detecting alternative or coexisting pathologies unrelated to diverticulitis. These advantages contribute to the ability of CT to provide comprehensive prognostic information[8,10,11].

Contrast-enhanced CT imaging in the portal venous phase is recommended. This approach is beneficial for assessing complicated diverticulitis because CT grading after the initial episode is crucial for predicting prognosis. Contrast-enhanced CT is superior to non-contrast studies in evaluating complicated cases. Additionally, the portal venous phase efficiently detects complications such as pylephlebitis. If there is clinical suspicion of diverticular bleeding, arterial-phase CT angiography is advised as it can localize the source of bleeding and reveal any structural causes. This information helps guide catheter-based angiographic procedures. Oral contrast is generally not recommended due to limited diagnostic benefits and the difficulty of administration. However, rectal contrast may be considered in suspected fistula cases[7,12,13].

Advantages of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are the lack of ionizing radiation, superior soft tissue contrast, and suitability for repeated imaging when necessary. MRI also offers significant advantages in special patient populations such as pregnant individuals. In cases where US findings are inconclusive, particularly during pregnancy, there has been a growing shift toward using non-contrast MRI as a second-line imaging modality[14]. However, MRI also has notable limitations, including longer acquisition times, higher costs, and reduced availability in emergency settings when compared with CT. While MRI has shown comparable sensitivity and specificity to CT in diagnosing ACD, further studies are needed to establish its broader clinical utility[15].

In the existing literature the radiological features of diverticular disease have predominantly been described for CT due to its rapid accessibility and widespread availability. Furthermore, most staging classifications are based on CT imaging. This review primarily focused on the CT findings associated with diverticular disease.

In 1978, Hinchey et al[16] classified patients with acute diverticulitis into four stages based on intraoperative findings as follows: Stage 1 represented pericolic phlegmon; stage 2 described intraabdominal abscess; stage 3 involved purulent peritonitis; and stage 4 was characterized by fecal peritonitis resulting from a large perforation. With advancements in CT technology and its increasing utilization over time, Kaiser et al[17] integrated imaging findings into Hinchey’s intraoperative classification and created the Modified Hinchey Classification in 2005. This modification introduced stage 0 and subdivided stage 1 into 1A and 1B. Stage 0 was defined as colonic wall thickening in patients with clinical symptoms. Stage 1A was defined as colonic wall thickening accompanied by pericolic phlegmon, and stage 1B was defined as colonic wall thickening with an associated pericolic or mesocolic abscess.

The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) developed the AAST grading system for ACD. This classification provided more accurate guidance for surgical decision-making than the Hinchey classification. It yielded similar predictive outcomes for complications and procedural interventions. The AAST grading system evaluated patients clinically, radiologically, operatively, and pathologically to categorize disease severity from stage 1, representing mild disease, to stage 5, indicating severe disease[18,19].

In 2015 the World Society of Emergency Surgery introduced the Sartelli classification, which is based on radiological findings. According to this classification, patients are divided into two main groups: Complicated and uncomplicated. Complicated cases are further categorized into four stages, with stages 1 and 2 subdivided into subgroups A and B[20]. The detailed staging criteria of the classification systems are presented in a comparative table (Table 1).

| Stage | Hinchey classification[16] | Modified Hinchey classification by Kaiser et al[17] | AAST grade[18] | WSES classification by Sartelli et al[20] |

| 0 | N/A | Mild clinical diverticulitis | N/A | Uncomplicated diverticulitis |

| 1 | Pericolic abscess or phlegmon | 1A: Confined pericolic inflammation-phlegmon | Colonic inflammation | 1A: Pericolic air bubbles or little pericolic fluid without abscess |

| 1B: Pericolic-mesocolic abscess | 1B: Abscess ≤ 4 cm | |||

| 2 | Pelvic, distant intrabdominal, or retroperitoneal abscess | Pelvic, distant intraabdominal, or retroperitoneal abscess | Colon microperforation or pericolic phlegmon without abscess | 2A: Abscess > 4 cm |

| 2B: Distant air (> 5 cm from inflamed bowel segment) | ||||

| 3 | Generalized purulent peritonitis | Generalized purulent peritonitis | Localized pericolic abscess | Diffuse fluid without distant free air (no hole in colon) |

| 4 | Generalized fecal peritonitis | Generalized fecal peritonitis | Distant and/or multiple abscesses | Diffuse fluid with distant free air (persistent hole in the colon |

| 5 | N/A | N/A | Free colonic perforation with generalized peritonitis | N/A |

The staging systems for diverticulitis have specific advantages and limitations. Although the Hinchey classification holds historical significance, it relies on intraoperative findings and lacks sufficient detail for imaging-based staging. The Modified Hinchey system adapts these principles to include radiological use yet remains relatively simplistic. The AAST classification combines clinical, radiological, and surgical factors to create a comprehensive classification system; however, its complexity may limit its routine use. The World Society of Emergency Surgery endorses the Sartelli classification and provides a thorough CT-based approach for clinical staging. It is simpler than the AAST classification and is easily applicable in routine emergency settings. This review presented the approach to acute diverticulitis primarily through the framework of the Sartelli classification.

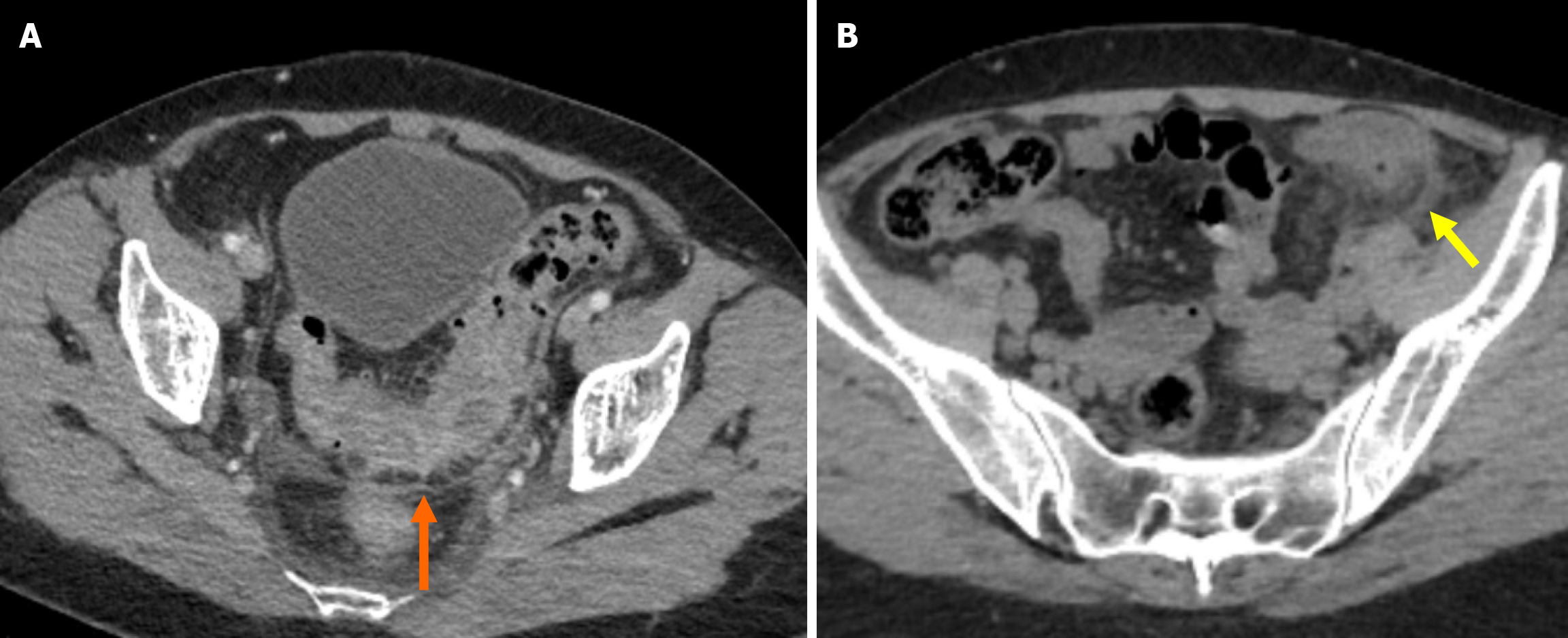

The thickening of the colonic wall with diverticula is defined as an increase in the density of the pericolic fat[20]. A hallmark feature of ACD is the moderate focal thickening of the colonic wall accompanied by disproportionately pronounced fat stranding. Additional indicative signs of the inflammatory process include mesenteric vessel engorgement, commonly referred to as the centipede sign, and fluid accumulation at the root of the sigmoid mesentery, known as the comma sign (Figure 1)[21-23].

The thickness of the colonic wall is determined by measuring the maximum distance perpendicular to the central axis from the serosal to the mucosal surface, excluding extramural components such as abscesses and the lumen of the filled bowel segment. In cases where the lumen cannot be identified, the total serosa-to-serosa distance is measured and divided by two. The wall thickness is considered normal for a distended segment up to 3 mm and in a collapsed segment up to 8 mm (Figure 2)[22,24,25].

Diverticular inflammation in complicated cases is often associated with microperforation/perforation and abscess formation. The Sartelli classification emphasizes imaging findings more than the Hinchey classification. It categorizes complicated diverticulitis in stages 3 and 4 based on the presence of extraluminal gas and fluid either adjacent to or distant from the inflamed bowel loop. In contrast the Hinchey classification differentiates these stages based on purulent or fecal peritonitis. Sartelli et al[26] subdivided staging according to abscess size, using 4 cm as the threshold to distinguish between stages 1B and 2A. These criteria aid clinicians in determining the appropriate treatment approach and the most suitable intervention[16,20,26].

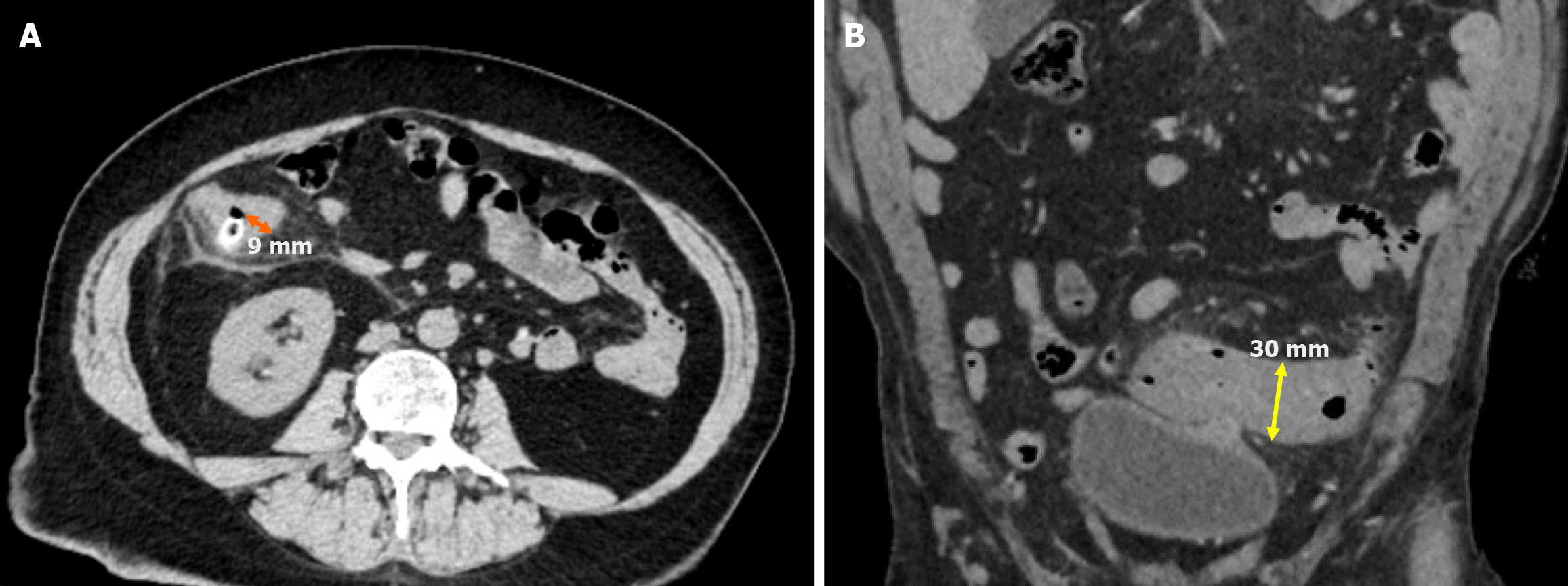

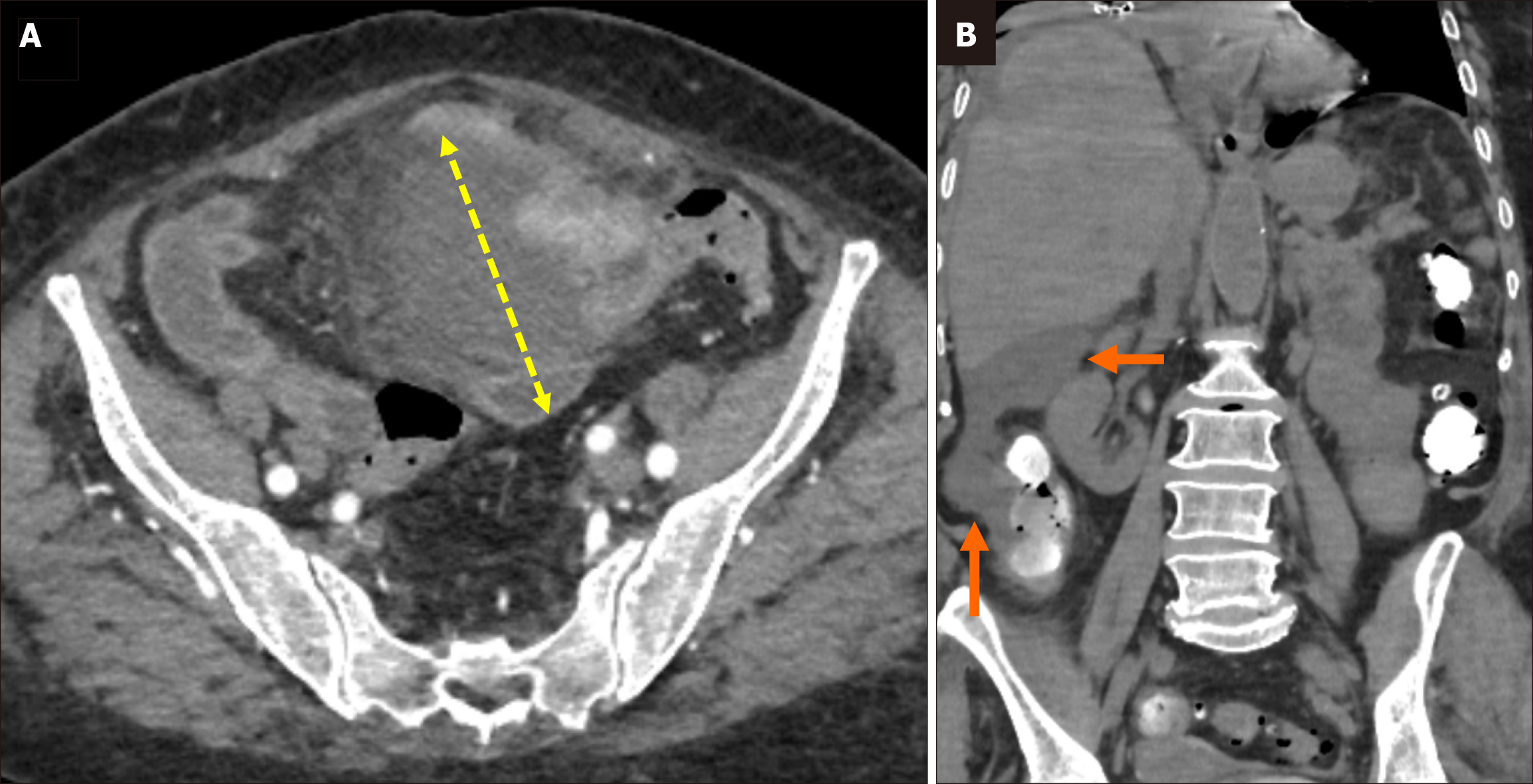

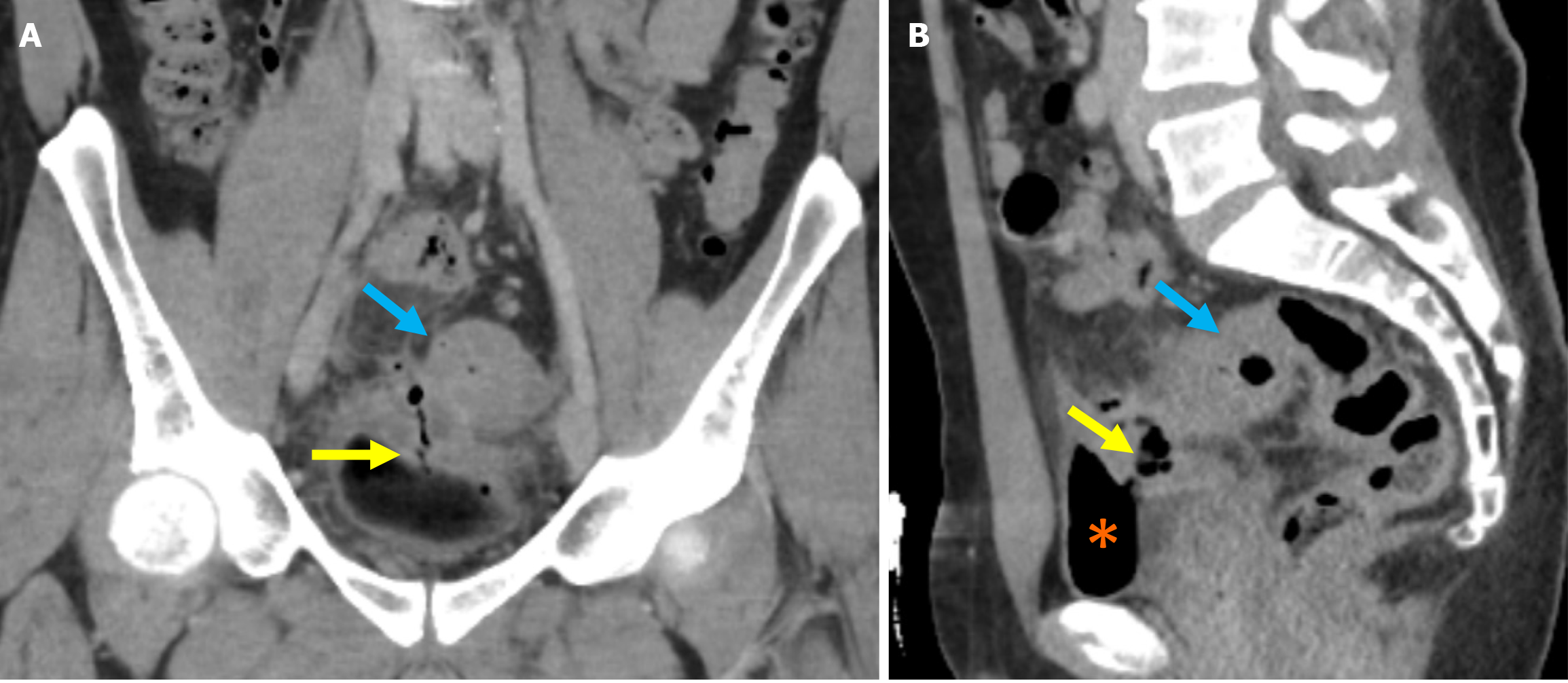

Stage 1A: Diverticular inflammation with microperforation without abscess formation and/or peritoneal involvement is the defining characteristic of stage 1A. On CT imaging it appears as pericolic air pockets or a small amount of pericolic fluid. In patients without evidence of distant air on CT, broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy is considered sufficient for management (Figure 3A).

Stage 1B: Stage 1B is defined as the presence of an abscess with a diameter of less than 4 cm. Treatment options include antibiotic therapy or percutaneous drainage (Figure 3B).

Stage 2A: Stage 2A is defined as the presence of an abscess with a diameter of more than 4 cm. Treatment options include antibiotic therapy or percutaneous drainage (Figure 4A).

Stage 2B: Stage 2B is characterized by the presence of distant air located more than 5 cm from the affected colonic loop without widespread peritoneal fluid. Although surgical intervention is generally preferred, conservative management may be considered in selected cases (Figure 4B).

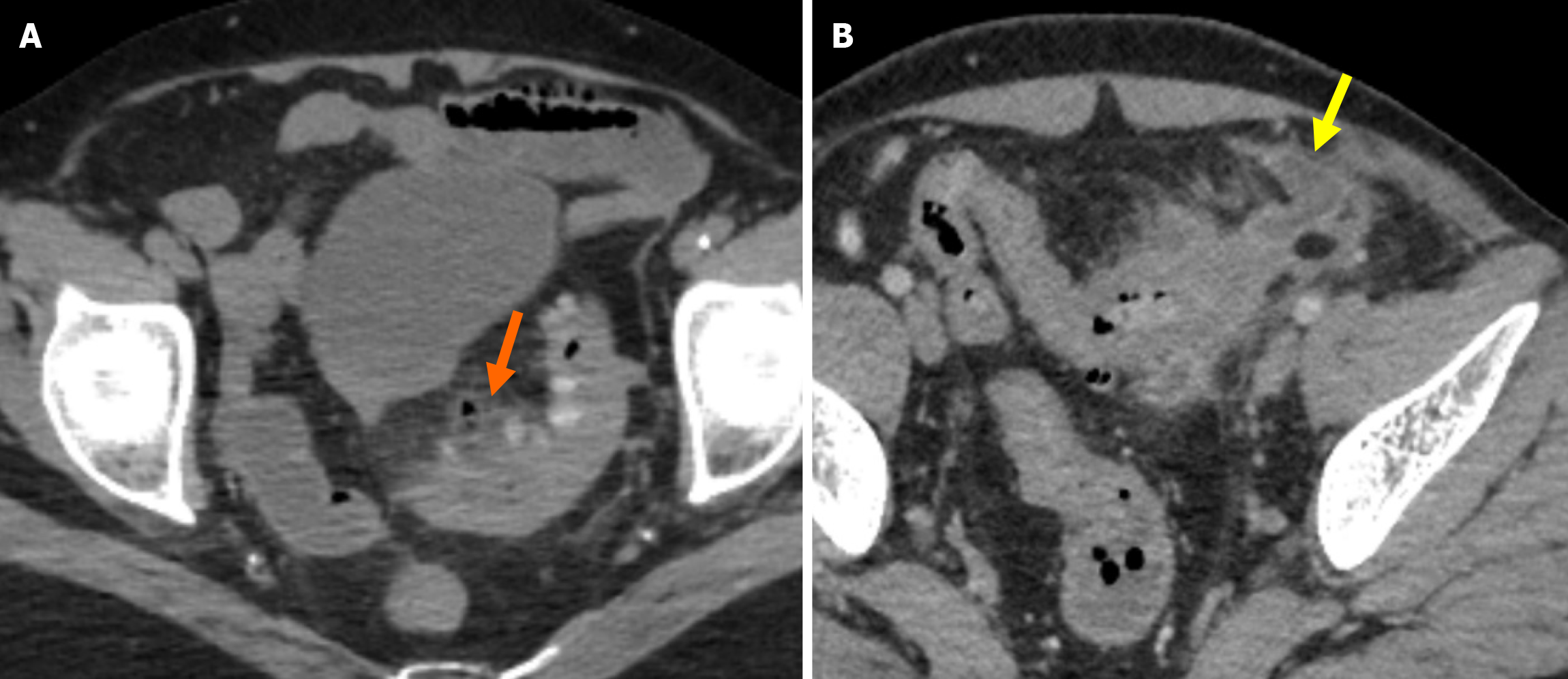

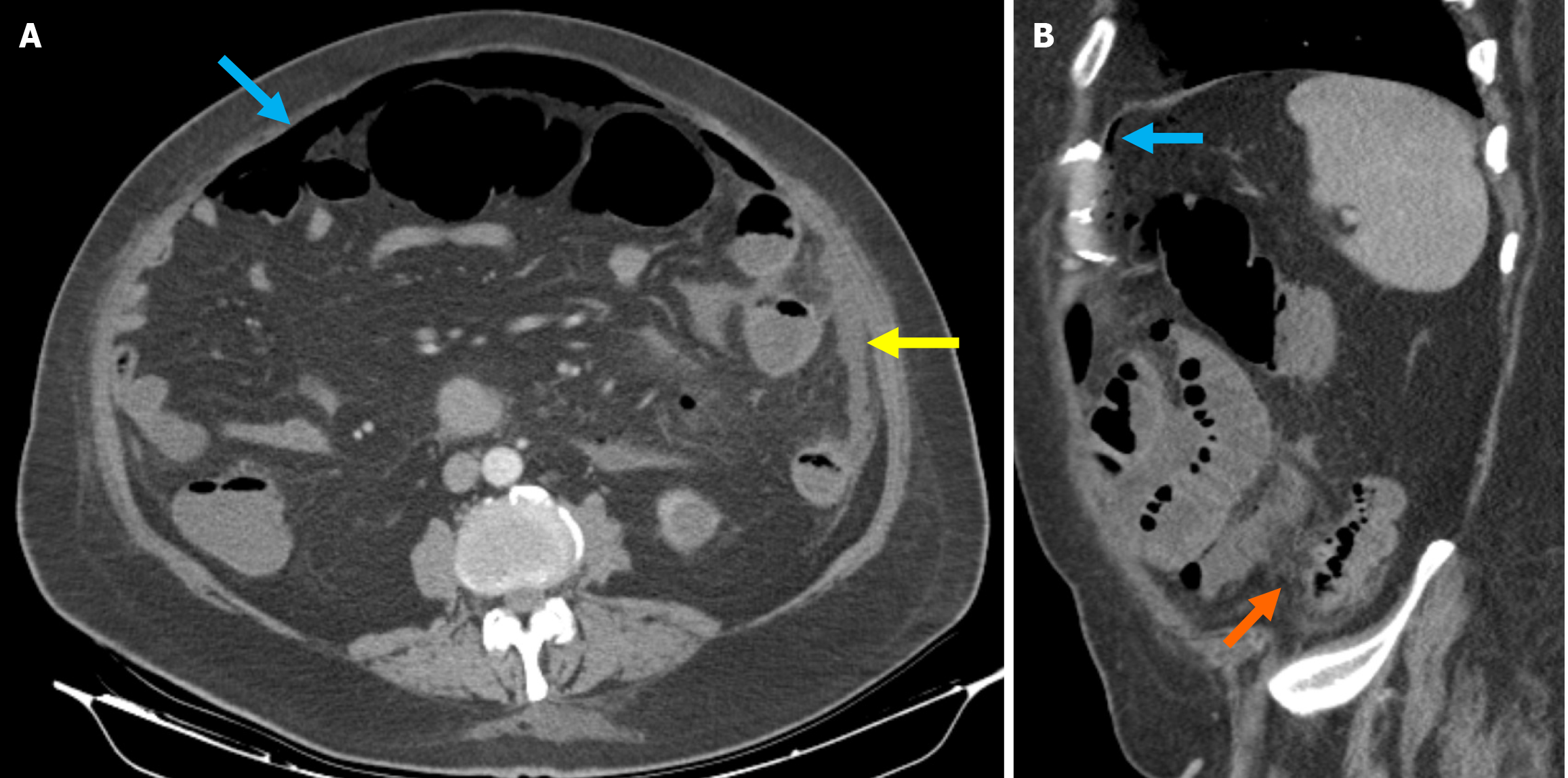

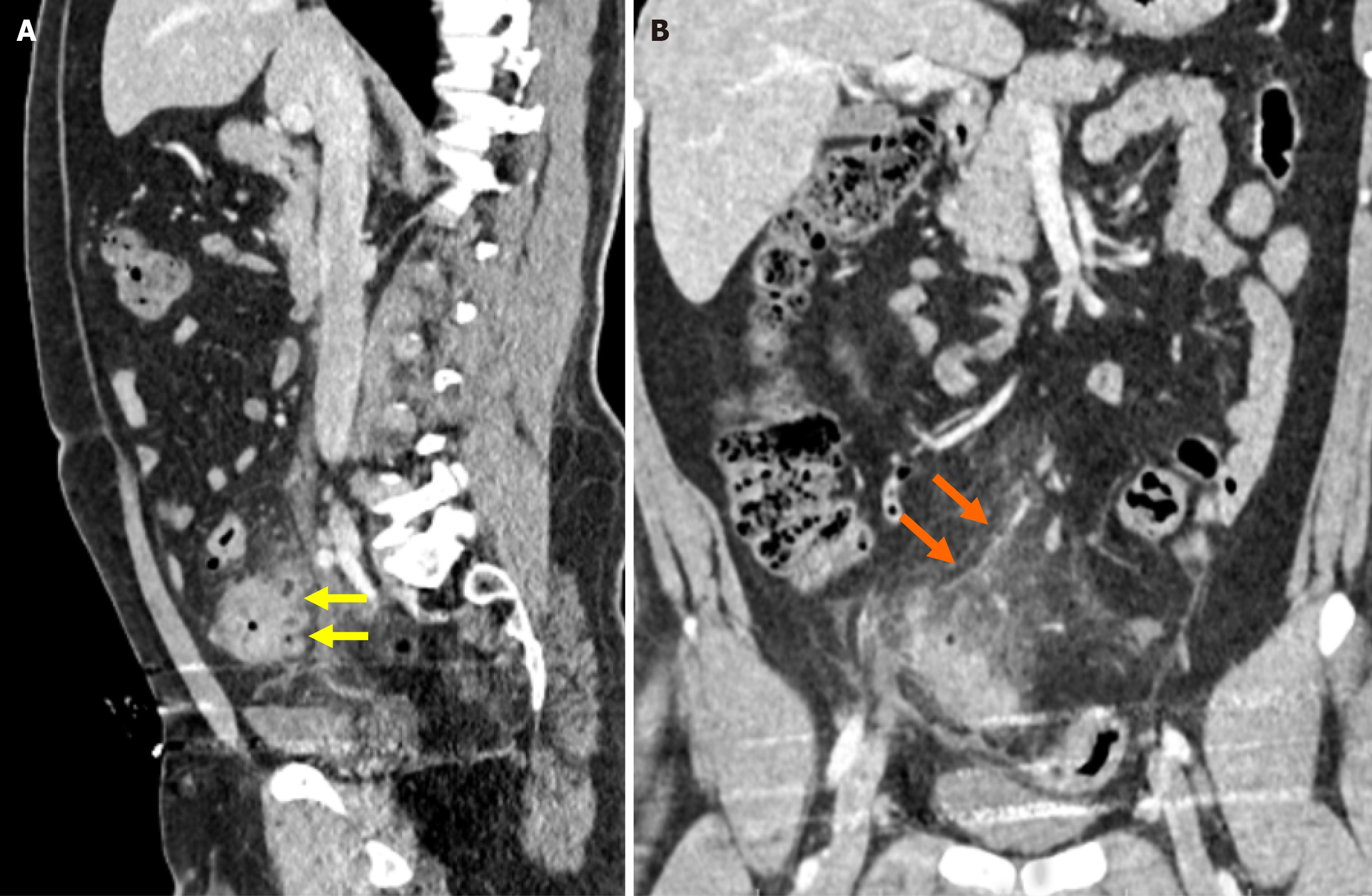

Stage 3: Stage 3 is defined as the presence of widespread fluid in at least two distant abdominal quadrants without free air. Treatment typically involves peritoneal lavage and colonic resection (Figure 5).

Stage 4: Stage 4 is characterized by the presence of widespread fluid and distant free air secondary to diverticular perforation. Hartmann’s resection is the preferred treatment approach (Figure 6).

Small perforations frequently occur during diverticulitis and are commonly managed with antibiotics and supportive care. However, uncontrolled perforations may lead to severe complications such as abscess formation, pylephlebitis, bowel obstruction, hemorrhage, and fistula, which all necessitate aggressive interventions. Recognizing and appro

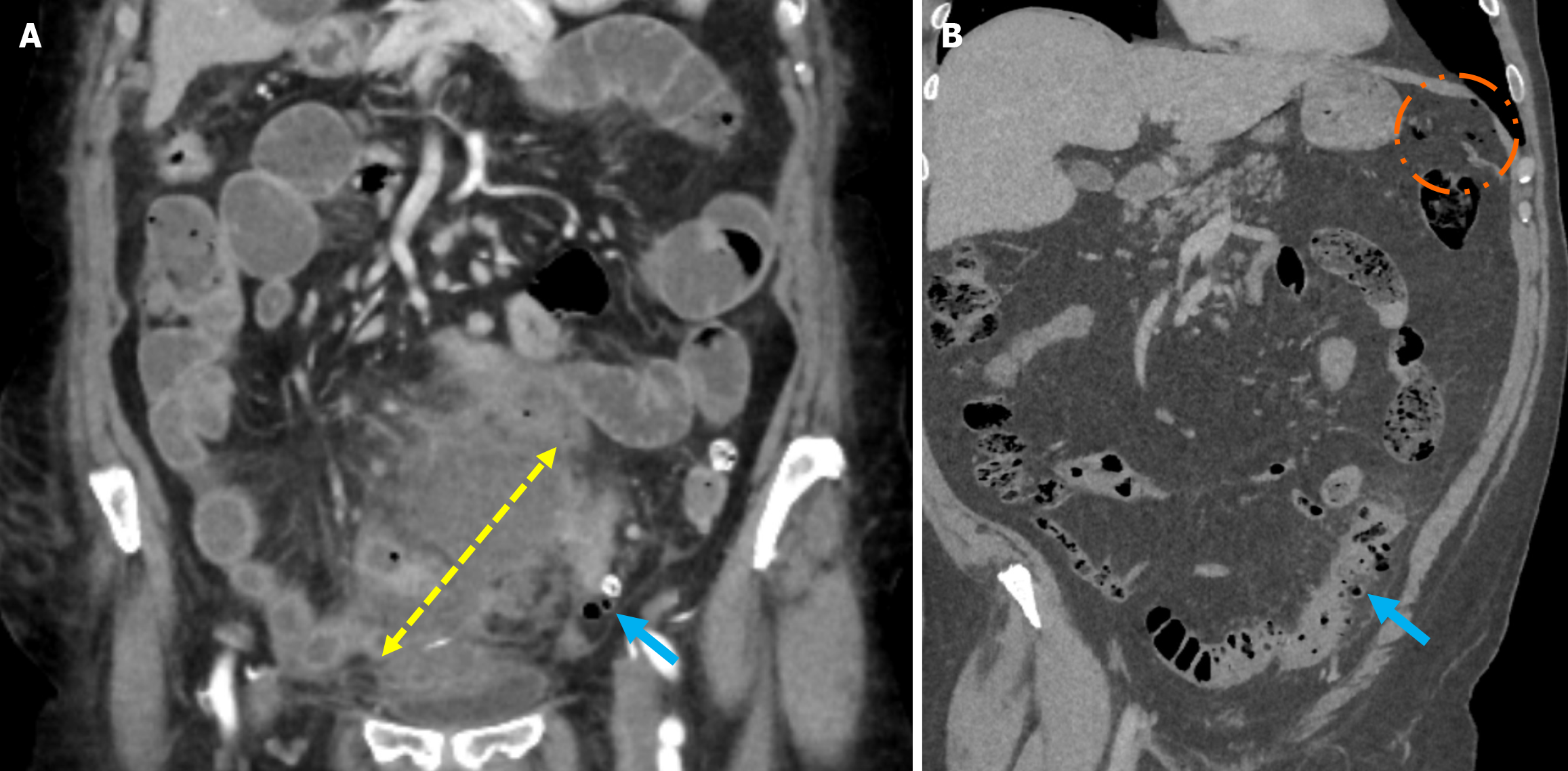

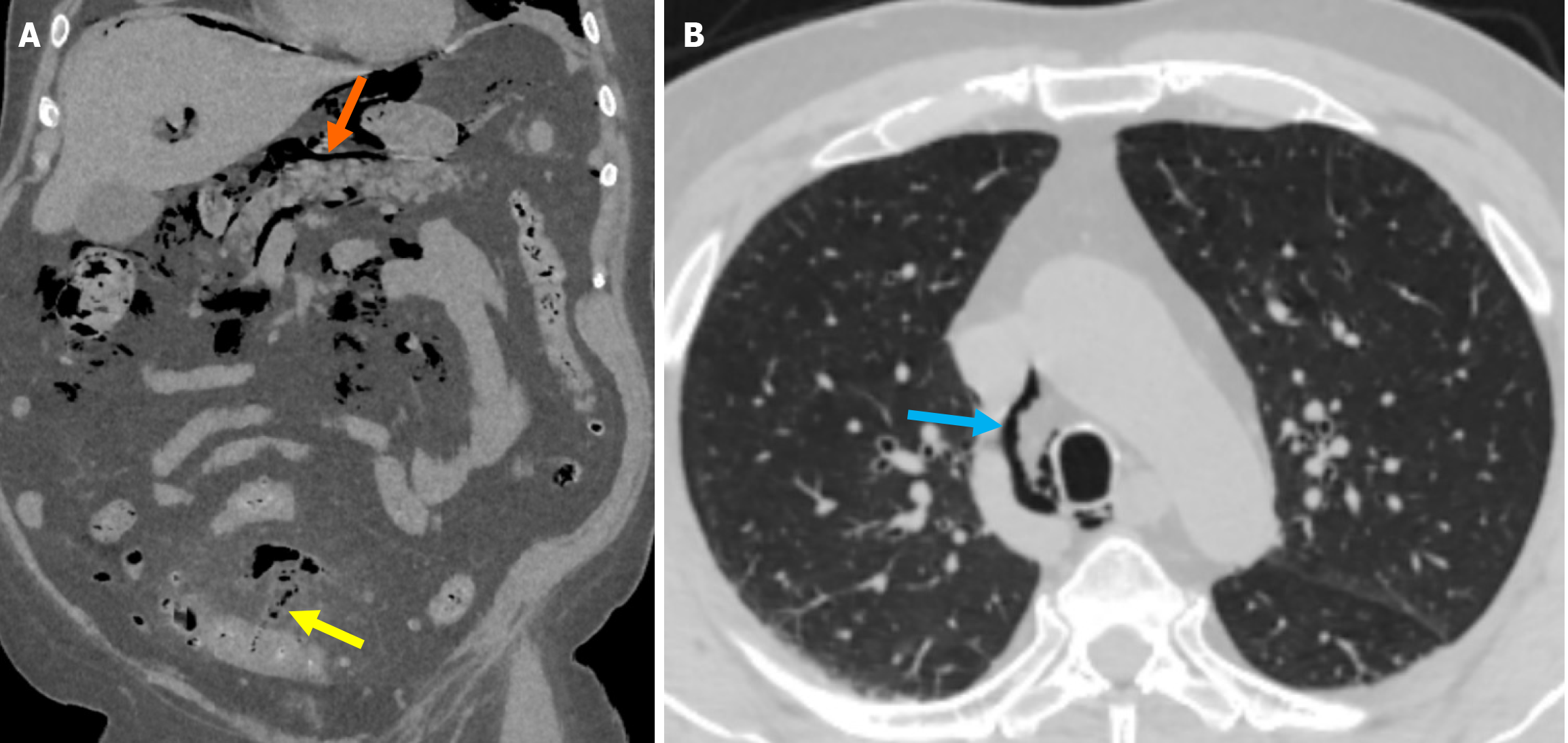

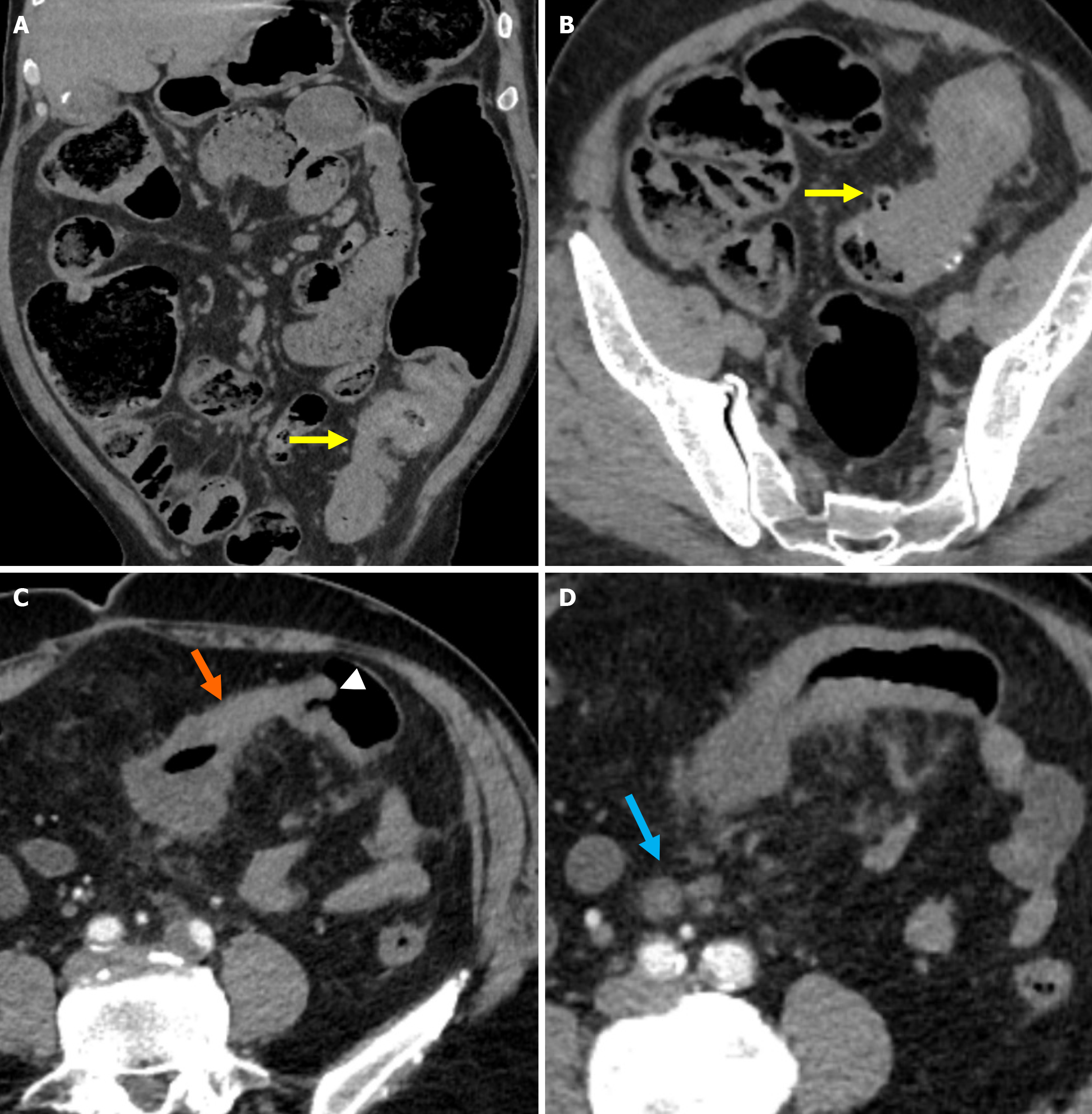

Perforation: Severe inflammation of the diverticulum can lead to bacterial overgrowth, impaired perfusion, hypoxia, necrosis, and loss of intestinal wall integrity, ultimately resulting in perforation[5]. Perforations typically occur in sigmoid colonic diverticulitis. They are characterized by localized free air adjacent to the inflamed colon, which remains self-contained. Clinical findings depend on the perforation site in cases where diverticular perforation is not self-limiting. Perforations on the peritoneal surface result in intraperitoneal free air, whereas those occurring on the mesenteric surface may allow free air to track retroperitoneally, potentially extending to the perirenal space, mediastinum, or even the scrotal sac[4,6,27-29]. Perforation can be directly identified on CT as bowel wall integrity disruption, extraluminal gas, and leakage of contrast material. Indirect signs include segmental wall thickening, inflammatory fat stranding, and the presence of an abscess (Figure 7)[6].

Abscess: Abscess formation can occur intramurally, pericolic, or at a distant location and typically develops as a pro

Abscesses secondary to diverticulitis can develop in distant organs such as the liver, lungs, spine, and brain. Microorganisms may translocate through mucosal defects, enter the portal system, and spread hematogenously to the liver and other organs. The formation of abscesses in distant organs significantly increases the morbidity and mortality associated with the disease[30,31].

A tubo-ovarian abscess should be considered in the differential diagnosis and as a possible consequence of di

Fistula: Two mechanisms are thought to play a role in fistula formation. The first involves direct erosion and adhesion of the ruptured diverticulum to the adjacent tissue due to the inflammatory process. The second mechanism occurs when a diverticular abscess erodes the surrounding tissue and forms a fistula[34].

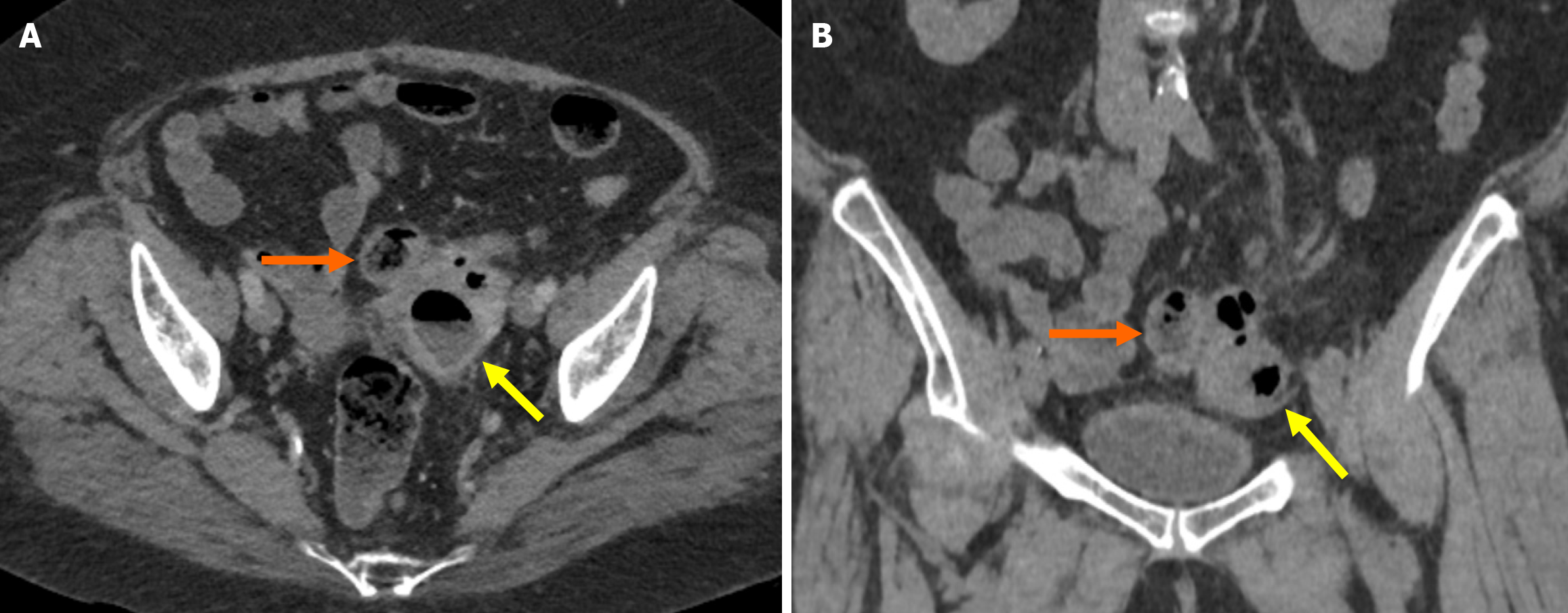

The most common fistula occurs between the sigmoid colon and the bladder. This occurrence presents as recurrent urinary tract infections, fecaluria, and pneumaturia. On CT imaging the loss of fat plane separation between the colonic loop and the bladder and the thickening of the adjacent colonic and bladder walls is observed. Additionally, the presence of air within the bladder and the passage of contrast material from a rectal or urinary foley catheter through the fistula are diagnostic findings[35,36]. Another common cause of vesicointestinal fistula is Crohn’s disease (CD). However, CD-related fistulas typically occur between the terminal ileum and the bladder and primarily affect the right side of the bladder. Fistulas secondary to diverticulitis most commonly involve the left posterior aspect of the bladder[27].

Depending on the location of diverticulitis, fistulous tracts will less commonly develop toward adjacent bowel loops, the uterus, gallbladder, vagina, or the skin[37]. Myometrial abscess formation and free air within the endometrial cavity are commonly observed in colo-uterine fistulas[38]. Fluid-sensitive sequences can depict the fistulous tract as a fluid-filled channel on MRI and CT, aiding in the diagnosis (Figure 9).

Pylephlebitis: Pylephlebitis is ascending septic thrombophlebitis. It is not specific to diverticulitis, occurring in other intraabdominal infections. Pylephlebitis is a rare condition, with an incidence ranging from 0.37 to 2.7 cases per 100000 person-years. It typically presents as nonspecific symptoms such as abdominal pain, leading to delayed diagnosis. The condition may progress to septic shock and carries a mortality rate of 8.7%-32.0%[39]. The primary treatment for py

The affected mesenteric vessels are associated with the venous structures responsible for draining the colonic segment involved in diverticulitis. For example, the sigmoid colon is the most commonly affected site in diverticulitis, and phlebitis initially manifests in the local venous structures draining the sigmoid colon, followed by thrombus formation in the inferior mesenteric vein and portal vein. In more advanced cases, pulmonary septic thromboembolism secondary to diverticulitis has also been reported[13,41,42].

Early hepatic abnormalities are characterized by non-opacified intrahepatic branches of the portal vein and central or peripheral regions of low attenuation, resulting from reduced intrahepatic blood flow. Hepatic abscess formation may occur if appropriate treatment is not administered. Then a more complex therapeutic approach is necessary (Figure 10)[13].

Bleeding: Diverticular bleeding is the leading cause of lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage[43]. Although endoscopy facilitates the diagnosis and treatment of diverticular bleeding, studies have shown that the combination of colonoscopy following contrast-enhanced CT improves the detection rate of the bleeding source[44].

Diverticular bleeding typically results from hemorrhage of an ectatic vessel within a chronic diverticular focus. Since early intervention is crucial for effective management, a colonoscopy within the first 12-24 hours is recommended. In cases of massive bleeding, the utility of a colonoscopy may be limited due to the need for bowel preparation and procedural constraints. Therefore, CT angiography is often preferred because it does not require prior preparation and is not restricted by the bleeding volume. The presence of intraluminal contrast extravasation following intravenous contrast administration suggests active bleeding. Oral contrast administration is not recommended in patients suspected of bleeding as it may obscure extravasation. On non-contrast imaging, hyperdense intraluminal content may indicate hemorrhage, while dynamic studies demonstrating contrast extravasation in the portal venous phase further support the presence of active bleeding[4,45,46].

Patients with chronic diverticulitis experience abdominal pain and obstructive symptoms lasting for at least 2 months without fever or leukocytosis. Pathological findings demonstrate that fibrosis is linked to acute or chronic inflammatory changes[47]. Recurrent acute diverticular episodes lead to chronic muscular hypertrophy, wall thickening, and fibrosis of the colon, ultimately resulting in luminal narrowing. This condition may mimic or obscure malignancy, and differentiation is made through CT imaging and endoscopic evaluation[4].

The most significant findings supporting diverticulitis on CT imaging include pericolic inflammation and segmental involvement exceeding 10 cm. Findings indicative of colon cancer include the presence of pericolic lymph nodes and a luminal mass[48,49]. The absence of diverticula in the affected segment and the presence of the shoulder phenomenon (wall thickening that forms a mass with an abrupt, perpendicular transition to the adjacent colonic mucosa) are additional distinguishing features of colon cancer. The luminal narrowing is also frequently associated with this finding[4,48,49]. In some patients, follow-up imaging and colonoscopy evaluation can provide a more accurate diagnosis (Figure 11)[4].

Segmental colitis associated with diverticulosis (SCAD) is characterized by active chronic luminal mucosal inflammation involving the colonic segment affected by diverticulitis. It is most frequently localized in the sigmoid colon, and the disease often presents with rectal bleeding. Differentiation from other conditions, such as CD, ulcerative colitis, and infectious colitis, can be challenging[50].

In elderly patients with a history of diverticulitis attacks and isolated inflammation localized to the sigmoid colon, SCAD should be considered. Diagnosis of SCAD requires a combination of endoscopic findings and clinical history. The preservation of the proximal colon and rectum and the typical older age of affected patients distinguishes SCAD from ulcerative colitis. However, SCAD shares similar CT findings with CD. In CD the gastrointestinal tract (most notably the terminal ileum) is affected in a segmental pattern. The length of segmental inflammation is greater in SCAD cases than in CD and diverticulitis. While diverticulitis typically presents with inflammation centered around the diverticular areas, SCAD is characterized by mucosal inflammation within the interdiverticular regions. Systemic symptoms such as fever and diarrhea are more frequently observed in infectious colitis[51,52].

In a study conducted by Urquhart et al[53], CT features associated with SCAD were described as concentric colonic wall thickening not centered around the diverticula, prominent mesenteric vascularity, and mild pericolic inflammation. The length of the affected segment in the sigmoid colon was greater in SCAD compared with CD and diverticulitis. Moreover, findings such as inflamed diverticula and pericolic fat stranding were less commonly observed in SCAD than in diverticulitis.

The growing presence of artificial intelligence (AI) in radiology is evident across all stages of the imaging process. AI enables faster and clearer image generation, helping clinicians make more confident diagnoses and informed treatment plans[54]. AI also enables precise analysis of numerous quantitative imaging features that are imperceptible to human senses through techniques such as radiomics and deep learning. By assessing and quantifying body composition, AI can provide valuable insights into disease severity and progression[54,55].

In a 2022 study conducted within a healthcare-focused AI competition, CT datasets were developed to evaluate six abdominal emergencies including diverticulitis. Diverticulitis was identified as the most challenging to detect due to the imaging similarities with other conditions, the scarcity of representative cases, and the lack of prominent distinguishing features. Despite typical CT signs such as bowel wall thickening and pericolic fat stranding, it often mimics pathologies like appendicitis or colitis, complicating its diagnosis[56].

AI has become increasingly prevalent in radiology, and current research on its application to diverticulitis has mainly concentrated on its role in differentiating diverticulitis from colorectal cancer. In a study conducted by Ziegelmayer et al[57], a cohort of 585 patients with a history of surgery for either colorectal cancer or acute diverticulitis was evaluated using a three-dimensional convolutional neural network. On the test set the model achieved a sensitivity of 83.3% and a specificity of 86.6%. Radiologist-only readings yielded a sensitivity of 77.6% and a specificity of 81.6%. When AI-supported radiologists were involved, sensitivity increased to 85.6% and specificity to 91.3%. Furthermore, the false-negative rate decreased from 22.0% to 14.3%.

The improvement in diagnostic accuracy for imaging interpretation in patients with colorectal cancer or acute diverticulitis is clinically significant. It is important because both conditions may require emergency surgery in the event of perforation; however, the surgical approaches differ substantially. Colorectal cancer typically necessitates oncological resection of the affected bowel segment along with the regional lymphatic basin, whereas limited resection of the diseased bowel segment is often sufficient in cases of acute diverticulitis[58].

Limitations of this narrative review should be acknowledged. One limitation was the inclusion of only English-language papers. The recent emergence of certain conditions as distinct entities and the limited availability of prospective studies on these topics also posed challenges during the preparation of this manuscript. Because SCAD was described only recently, there are limited dedicated imaging features and related studies, which may affect the generalizability of the findings. Few prospective studies have concentrated on the use of AI in diverticular disease. Further studies are warranted to confirm the role of new tools, such as AI, across various clinical situations.

Diverticular disease is a prevalent gastrointestinal disorder, and its incidence continues to increase due to evolving dietary habits and lifestyle changes in modern populations. The presenting symptoms leading to hospital admission depend on whether the disease is complicated or uncomplicated. The advantages of utilizing US for assessing diverticular disease are the ease of use, no risks associated with ionizing radiation, cost-effectiveness, and diagnostic accuracy comparable with CT. However, US is less effective than CT in identifying complicated diverticular disease and differentiating from other mimicking pathologies, which limits its use in these clinical scenarios. CT is crucial in diagnosing, identifying complications, and guiding disease staging using the Sartelli classification.

The stage of the disease can be determined to allow clinicians to predict the clinical course and select from a broad spectrum of treatment options ranging from conservative management to percutaneous drainage or surgical intervention. In addition to providing valuable information about diverticulitis, CT imaging is critical for differentiating alternative diagnoses and identifying concurrent pathologies during diagnosis and follow-up. In SCAD cases imaging alone is insufficient, and diagnosis requires integrating clinical findings and endoscopic features.

As in numerous medical domains, AI is increasingly important in the radiological evaluation of diverticulitis, with recent promising efforts focusing on its effectiveness in differentiating it from colorectal cancer. For radiologists, understanding the current staging systems and recognizing the imaging findings associated with common complications are essential to facilitate effective communication with surgeons and gastroenterologists and to ensure accurate diagnosis and appropriate management planning for patients.

| 1. | Feuerstein JD, Falchuk KR. Diverticulosis and Diverticulitis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:1094-1104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Young-Fadok TM. Diverticulitis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1635-1642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bharucha AE, Parthasarathy G, Ditah I, Fletcher JG, Ewelukwa O, Pendlimari R, Yawn BP, Melton LJ, Schleck C, Zinsmeister AR. Temporal Trends in the Incidence and Natural History of Diverticulitis: A Population-Based Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1589-1596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 240] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sugi MD, Sun DC, Menias CO, Prabhu V, Choi HH. Acute diverticulitis: Key features for guiding clinical management. Eur J Radiol. 2020;128:109026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wedel T, Barrenschee M, Lange C, Cossais F, Böttner M. Morphologic Basis for Developing Diverticular Disease, Diverticulitis, and Diverticular Bleeding. Viszeralmedizin. 2015;31:76-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sessa B, Galluzzo M, Ianniello S, Pinto A, Trinci M, Miele V. Acute Perforated Diverticulitis: Assessment With Multidetector Computed Tomography. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2016;37:37-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Flor N, Maconi G, Cornalba G, Pickhardt PJ. The Current Role of Radiologic and Endoscopic Imaging in the Diagnosis and Follow-Up of Colonic Diverticular Disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2016;207:15-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Liljegren G, Chabok A, Wickbom M, Smedh K, Nilsson K. Acute colonic diverticulitis: a systematic review of diagnostic accuracy. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9:480-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kandagatla PG, Stefanou AJ. Current Status of the Radiologic Assessment of Diverticular Disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2018;31:217-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Laméris W, van Randen A, Bipat S, Bossuyt PM, Boermeester MA, Stoker J. Graded compression ultrasonography and computed tomography in acute colonic diverticulitis: meta-analysis of test accuracy. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:2498-2511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ripollés T, Sebastián-Tomás JC, Martínez-Pérez MJ, Manrique A, Gómez-Abril SA, Torres-Sanchez T. Ultrasound can differentiate complicated and noncomplicated acute colonic diverticulitis: a prospective comparative study with computed tomography. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2021;46:3826-3834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tiralongo F, Di Pietro S, Milazzo D, Galioto S, Castiglione DG, Ini' C, Foti PV, Mosconi C, Giurazza F, Venturini M, Zanghi' GN, Palmucci S, Basile A. Acute Colonic Diverticulitis: CT Findings, Classifications, and a Proposal of a Structured Reporting Template. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13:3628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Balthazar EJ, Gollapudi P. Septic thrombophlebitis of the mesenteric and portal veins: CT imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2000;24:755-760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kechagias KS, Katsikas-Triantafyllidis K, Geropoulos G, Giannos P, Zafeiri M, Tariq-Mian I, Paraskevaidi M, Mitra A, Kyrgiou M. Diverticulitis during pregnancy: A review of the reported cases. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:942666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jerjen F, Zaidi T, Chan S, Sharma A, Mudliar R, Soomro K, Jimenez Y, Reed W. Magnetic Resonance Imaging for the diagnosis and management of acute colonic diverticulitis: a review of current and future use. J Med Radiat Sci. 2021;68:310-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hinchey EJ, Schaal PG, Richards GK. Treatment of perforated diverticular disease of the colon. Adv Surg. 1978;12:85-109. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Kaiser AM, Jiang JK, Lake JP, Ault G, Artinyan A, Gonzalez-Ruiz C, Essani R, Beart RW Jr. The management of complicated diverticulitis and the role of computed tomography. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:910-917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 419] [Cited by in RCA: 347] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Choi J, Bessoff K, Bromley-Dulfano R, Li Z, Gupta A, Taylor K, Wadhwa H, Seltzer R, Spain DA, Knowlton LM. Prospectively Assigned AAST Grade versus Modified Hinchey Class and Acute Diverticulitis Outcomes. J Surg Res. 2021;259:555-561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Shafi S, Aboutanos M, Brown CV, Ciesla D, Cohen MJ, Crandall ML, Inaba K, Miller PR, Mowery NT; American Association for the Surgery of Trauma Committee on Patient Assessment and Outcomes. Measuring anatomic severity of disease in emergency general surgery. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76:884-887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sartelli M, Moore FA, Ansaloni L, Di Saverio S, Coccolini F, Griffiths EA, Coimbra R, Agresta F, Sakakushev B, Ordoñez CA, Abu-Zidan FM, Karamarkovic A, Augustin G, Costa Navarro D, Ulrych J, Demetrashvili Z, Melo RB, Marwah S, Zachariah SK, Wani I, Shelat VG, Kim JI, McFarlane M, Pintar T, Rems M, Bala M, Ben-Ishay O, Gomes CA, Faro MP, Pereira GA Jr, Catani M, Baiocchi G, Bini R, Anania G, Negoi I, Kecbaja Z, Omari AH, Cui Y, Kenig J, Sato N, Vereczkei A, Skrovina M, Das K, Bellanova G, Di Carlo I, Segovia Lohse HA, Kong V, Kok KY, Massalou D, Smirnov D, Gachabayov M, Gkiokas G, Marinis A, Spyropoulos C, Nikolopoulos I, Bouliaris K, Tepp J, Lohsiriwat V, Çolak E, Isik A, Rios-Cruz D, Soto R, Abbas A, Tranà C, Caproli E, Soldatenkova D, Corcione F, Piazza D, Catena F. A proposal for a CT driven classification of left colon acute diverticulitis. World J Emerg Surg. 2015;10:3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Minordi LM, Larosa L, Berte G, Pecere S, Manfredi R. CT of the acute colonic diverticulitis: a pictorial essay. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2020;26:546-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Fernandes T, Oliveira MI, Castro R, Araújo B, Viamonte B, Cunha R. Bowel wall thickening at CT: simplifying the diagnosis. Insights Imaging. 2014;5:195-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Pereira JM, Sirlin CB, Pinto PS, Jeffrey RB, Stella DL, Casola G. Disproportionate fat stranding: a helpful CT sign in patients with acute abdominal pain. Radiographics. 2004;24:703-715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Dickerson EC, Chong ST, Ellis JH, Watcharotone K, Nan B, Davenport MS, Al-Hawary M, Mazza MB, Rizk R, Morris AM, Cohan RH. Recurrence of Colonic Diverticulitis: Identifying Predictive CT Findings-Retrospective Cohort Study. Radiology. 2017;285:850-858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wiesner W, Mortelé KJ, Ji H, Ros PR. Normal colonic wall thickness at CT and its relation to colonic distension. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2002;26:102-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sartelli M, Weber DG, Kluger Y, Ansaloni L, Coccolini F, Abu-Zidan F, Augustin G, Ben-Ishay O, Biffl WL, Bouliaris K, Catena R, Ceresoli M, Chiara O, Chiarugi M, Coimbra R, Cortese F, Cui Y, Damaskos D, De' Angelis GL, Delibegovic S, Demetrashvili Z, De Simone B, Di Marzo F, Di Saverio S, Duane TM, Faro MP, Fraga GP, Gkiokas G, Gomes CA, Hardcastle TC, Hecker A, Karamarkovic A, Kashuk J, Khokha V, Kirkpatrick AW, Kok KYY, Inaba K, Isik A, Labricciosa FM, Latifi R, Leppäniemi A, Litvin A, Mazuski JE, Maier RV, Marwah S, McFarlane M, Moore EE, Moore FA, Negoi I, Pagani L, Rasa K, Rubio-Perez I, Sakakushev B, Sato N, Sganga G, Siquini W, Tarasconi A, Tolonen M, Ulrych J, Zachariah SK, Catena F. 2020 update of the WSES guidelines for the management of acute colonic diverticulitis in the emergency setting. World J Emerg Surg. 2020;15:32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 41.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Onur MR, Akpinar E, Karaosmanoglu AD, Isayev C, Karcaaltincaba M. Diverticulitis: a comprehensive review with usual and unusual complications. Insights Imaging. 2017;8:19-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kim SH, Shin SS, Jeong YY, Heo SH, Kim JW, Kang HK. Gastrointestinal tract perforation: MDCT findings according to the perforation sites. Korean J Radiol. 2009;10:63-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Fosi S, Giuricin V, Girardi V, Di Caprera E, Costanzo E, Di Trapano R, Simonetti G. Subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastinum, pneumoretroperitoneum, and pneumoscrotum: unusual complications of acute perforated diverticulitis. Case Rep Radiol. 2014;2014:431563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Linsen PVM, Schrier VJMM. Decoding pylephlebitis: Tracing the path of infected thrombosis and liver abscesses. Radiol Case Rep. 2023;18:3820-3823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Navarrete D, Patil S, Dandachi D. Acute Streptococcus constellatus Pyogenic Liver Abscess Due to an Atypical Presentation of Sigmoid Diverticulitis Complicated by Pericolonic Abscess. Cureus. 2020;12:e10940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Metz Y, Nagler J. Diverticulitis presenting as a tubo-ovarian abscess with subsequent colon perforation. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;3:70-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Protopapas AG, Diakomanolis ES, Milingos SD, Rodolakis AJ, Markaki SN, Vlachos GD, Papadopoulos DE, Michalas SP. Tubo-ovarian abscesses in postmenopausal women: gynecological malignancy until proven otherwise? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;114:203-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Small WP, Smith AN. Fistula and conditions associated with diverticular disease of the colon. Clin Gastroenterol. 1975;4:171-199. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Najjar SF, Jamal MK, Savas JF, Miller TA. The spectrum of colovesical fistula and diagnostic paradigm. Am J Surg. 2004;188:617-621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Coakley KM, Davis BR, Kasten KR. Complicated Diverticular Disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2021;34:96-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Woods RJ, Lavery IC, Fazio VW, Jagelman DG, Weakley FL. Internal fistulas in diverticular disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31:591-596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Choi PW. Colouterine fistula caused by diverticulitis of the sigmoid colon. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 2012;28:321-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Maejima T, Hashimoto E, Hirose K, Miyazaki K, Suzuki M, Maeno T. Pylephlebitis Secondary to Diverticulitis Diagnosed by Abdominal Ultrasound and Computed Tomography. Cureus. 2024;16:e73358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Gajendran M, Muniraj T, Yassin M. Diverticulitis complicated by pylephlebitis: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Jevtic D, Gavrancic T, Pantic I, Nordin T, Nordstrom CW, Antic M, Pantic N, Kaljevic M, Joksimovic B, Jovanovic M, Petcu E, Jecmenica M, Milovanovic T, Sprecher L, Dumic I. Suppurative Thrombosis of the Portal Vein (Pylephlebits): A Systematic Review of Literature. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Wali L, Shah A, Sleiman S, Hogsand T, Humphries S. Acute pylephlebitis secondary to perforated sigmoid diverticulitis: A case report. Radiol Case Rep. 2021;16:1504-1507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Nagata N, Niikura R, Ishii N, Kaise M, Omata F, Tominaga N, Kitagawa T, Ikeya T, Kobayashi K, Furumoto Y, Narasaka T, Iwata E, Sugimoto M, Itoi T, Uemura N, Kawai T. Cumulative evidence for reducing recurrence of colonic diverticular bleeding using endoscopic clipping versus band ligation: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36:1738-1743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Nagata N, Niikura R, Aoki T, Moriyasu S, Sakurai T, Shimbo T, Shinozaki M, Sekine K, Okubo H, Watanabe K, Yokoi C, Yanase M, Akiyama J, Uemura N. Role of urgent contrast-enhanced multidetector computed tomography for acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding in patients undergoing early colonoscopy. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:1162-1172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Nagata N, Ishii N, Manabe N, Tomizawa K, Urita Y, Funabiki T, Fujimori S, Kaise M. Guidelines for Colonic Diverticular Bleeding and Colonic Diverticulitis: Japan Gastroenterological Association. Digestion. 2019;99 Suppl 1:1-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Schreyer AG, Layer G; German Society of Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (DGVS) as well as the German Society of General and Visceral Surgery (DGAV) in collaboration with the German Radiology Society (DRG). S2k Guidlines for Diverticular Disease and Diverticulitis: Diagnosis, Classification, and Therapy for the Radiologist. Rofo. 2015;187:676-684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Sheiman L, Levine MS, Levin AA, Hogan J, Rubesin SE, Furth EE, Laufer I. Chronic diverticulitis: clinical, radiographic, and pathologic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:522-528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Chintapalli KN, Chopra S, Ghiatas AA, Esola CC, Fields SF, Dodd GD 3rd. Diverticulitis versus colon cancer: differentiation with helical CT findings. Radiology. 1999;210:429-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Lips LM, Cremers PT, Pickhardt PJ, Cremers SE, Janssen-Heijnen ML, de Witte MT, Simons PC. Sigmoid cancer versus chronic diverticular disease: differentiating features at CT colonography. Radiology. 2015;275:127-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Schembri J, Bonello J, Christodoulou DK, Katsanos KH, Ellul P. Segmental colitis associated with diverticulosis: is it the coexistence of colonic diverticulosis and inflammatory bowel disease? Ann Gastroenterol. 2017;30:257-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Cassieri C, Brandimarte G, Elisei W, Lecca GP, Goni E, Penna A, Picchio M, Tursi A. How to Differentiate Segmental Colitis Associated With Diverticulosis and Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50 Suppl 1:S36-S38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Freeman HJ. Segmental Colitis Associated with Diverticulosis (SCAD). Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2023;25:130-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Urquhart SA, Ewy MW, Flicek KT, Fidler JL, Sheedy SP, Harmsen WS, Chedid VG, Coelho-Prabhu N. Clinical and Radiographic Characteristics in Segmental Colitis Associated With Diverticulosis, Diverticulitis, and Crohn's Disease. Gastro Hep Adv. 2024;3:901-909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Loper MR, Makary MS. Evolving and Novel Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Abdominal Imaging. Tomography. 2024;10:1814-1831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Rogers W, Thulasi Seetha S, Refaee TAG, Lieverse RIY, Granzier RWY, Ibrahim A, Keek SA, Sanduleanu S, Primakov SP, Beuque MPL, Marcus D, van der Wiel AMA, Zerka F, Oberije CJG, van Timmeren JE, Woodruff HC, Lambin P. Radiomics: from qualitative to quantitative imaging. Br J Radiol. 2020;93:20190948. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 40.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Koç U, Sezer EA, Özkaya YA, Yarbay Y, Beşler MS, Taydaş O, Yalçın A, Evrimler Ş, Kızıloğlu HA, Kesimal U, Atasoy D, Oruç M, Ertuğrul M, Karakaş E, Karademir F, Sebik NB, Topuz Y, Aktan ME, Sezer Ö, Aydın Ş, Varlı S, Akdoğan E, Ülgü MM, Birinci Ş. Elevating healthcare through artificial intelligence: analyzing the abdominal emergencies data set (TR_ABDOMEN_RAD_EMERGENCY) at TEKNOFEST-2022. Eur Radiol. 2024;34:3588-3597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Ziegelmayer S, Reischl S, Havrda H, Gawlitza J, Graf M, Lenhart N, Nehls N, Lemke T, Wilhelm D, Lohöfer F, Burian E, Neumann PA, Makowski M, Braren R. Development and Validation of a Deep Learning Algorithm to Differentiate Colon Carcinoma From Acute Diverticulitis in Computed Tomography Images. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2253370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Maguire LH, Alavi K, Sudan R, Wise PE, Kaiser AM, Bordeianou L. Surgical Considerations in the Treatment of Small Bowel Crohn's Disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;21:398-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |