Published online Sep 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i27.8071

Peer-review started: February 24, 2021

First decision: May 6, 2021

Revised: May 19, 2021

Accepted: August 5, 2021

Article in press: August 5, 2021

Published online: September 26, 2021

Processing time: 203 Days and 17.8 Hours

Primary pancreatic paragangliomas are extremely rare tumors. Limited by the diagnostic efficacy of histopathological examination, their malignant behavior is thought to be associated with local invasion or metastasis, with only four malignant cases reported in the literature to date. As pancreatic paragangliomas share similar imaging features with other types of pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms, they are difficult to diagnose accurately without the support of pathological evidence. As primary pancreatic paragangliomas are rare, especially those accompanied by lymph node metastasis, there is currently no consensus on treatment. Herein, we report a case of primary pancreatic paraganglioma with lymph node metastasis.

A mass located in the pancreatic body was incidentally discovered on computed tomography in a 41-year-old Tibetan man. Distal pancreatectomy was subsequently performed and a 4.1 cm × 4.2 cm tumor was found embedded in the body of the pancreas during surgery. Histological examination confirmed the characteristics of paraganglioma in which the neoplastic chief cells were arranged in a classic Zellballen pattern under hematoxylin-eosin staining. Further, immunohistochemistry demonstrated that the sustentacular cells in the tumor tissue were positive for S-100 protein, and neoplastic cells and pancreatic draining lymph nodes were positive for chromogranin A and synaptophysin; thus, the presence of lymph node metastasis (two of the eight resected pancreatic draining lymph nodes) was also confirmed. A diagnosis of primary pancreatic paraganglioma with lymph node metastasis was finally established. The patient remained disease-free for 1 year after the surgery.

A definite diagnosis of pancreatic paraganglioma mainly depends on posto

Core Tip: Paragangliomas are rare neuroendocrine tumors that originate from autonomic nervous systems, with a morbidity of only 2 to 8 in 1000000 of the population. Paragangliomas arising from the pancreas are even less, local invasion or metastasis are thought to be associated with malignant behaviors, and only four of these cases have been reported to date. It is difficult to make an accurate preoperative diagnosis of pancreatic paraganglioma especially when the tumor is non-functioning. No standard therapeutic consensus has been reached yet. Herein, we present a case of primary pancreatic paraganglioma with lymph node metastasis and discuss the related issues.

- Citation: Jiang CN, Cheng X, Shan J, Yang M, Xiao YQ. Primary pancreatic paraganglioma harboring lymph node metastasis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(27): 8071-8081

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i27/8071.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i27.8071

Paragangliomas are rare neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) that originate from neural crest cells, with a morbidity of only 2 to 8 in 1000000 of the population and a malignancy rate of 10%-50%[1]. Diagnosis mainly relies on the pathology. Paragangliomas derived from the adrenal medulla are referred to as pheochromocytomas. Extra-adrenal paragangliomas can arise at sites where paraganglia are known to occur, including the parasympathetic nervous system of the head and neck, mediastinal compartments of the chest, and retroperitoneum of the abdomen[2-4]. Primary paragangliomas arising in the pancreas are extremely rare, as there have been only 19 cases reported worldwide to date[1,5-20], with four of these cases accompanied by lymph node metastasis or distant metastasis[10,11,14,20] (Table 1). The criteria for malignancy based on histopathological examination are not well defined; therefore, the presence of specific local invasion or metastasis is a reliable diagnostic feature[21]. Due to the rarity of this tumor, no standard therapeutic consensus has been reached. Currently, the preferred treatment for pancreatic paraganglioma is surgical resection[1,17]. In this paper, we report a case of primary pancreatic paraganglioma with lymph node metastasis and discuss the clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment strategies.

| Ref. | Sex | Age | Size (cm) | Location | Imaging features | Manifestation | Preoperative diagnosis | Therapy | Follow-up |

| Fujino et al[5], 1998 | M | 61 | 2.5 × 2.0 × 1.8 | Uncinate process | CT: A solid mass. MRI: An isointensity lesion. CA: A hypervascular tumor | NF | Pan-NEN | PD | 5 yr PO (TF) |

| Parithivel et al[6], 2000 | M | 85 | 6 | Head | CT: A highly vascular solid-cystic mass, no dilation of either biliary or pancreatic ducts | NF | NM | TLR | NM |

| Ohkawara et al[7], 2005 | F | 72 | 4 | Head | CT: A solid-cystic tumor rich in blood supply, no dilation of either biliary or pancreatic ducts | NF | Pan-NEN | RPH | NM |

| Kim et al[8], 2008 | F | 57 | 6.5 × 6 × 6 | Head | US: A hypervascular tumor. CT: Marked enhancement in the arterial phase, still well-enhancing in the portal venous phase, non-enhancing tubular-shaped portions could be seen inside. EUS: Echogenic mass with several anechoic portions | NF | Pancreatic islet cell tumor | PPPD | NM |

| He et al[9], 2011 | F | 40 | 4.5 × 4.2 | Uncinate process | CT: Well demarcated solid mass, dramatical enhancement in pancreatic and portal vein phase, several low density foci were observed. Distal pancreatic duct middle dilation | NF | NM | RPH | NM |

| Higa and Kapur[10], 2012 | F | 65 | 2.0 | Uncinate process | CT: A pancreatic mass with enhancement and mixed attenuation | NF | NM | PD | NM |

| Al-Jiffry et al[11], 2013 | F | 19 | 9.0 | Head | CT: Marked enhancement in the arterial phase and washed out in the venous phase | F | Pancreatic sarcoma | PD | 3 yr PO (TF) |

| Borgohain et al[12], 2013 | F | 55 | 17 × 19 | Tail | CT: A multi-cystic tumor. US: Highly vascular | NF | NM | TLR | 10 mo PO (TF) |

| Straka et al[13], 2014 | F | 53 | 8.5 | Head | CT: An extremely hypervascular tumor with abundant collateral vessels from the superior mesenteric artery | NF | NM | PPPD | 49 mo PO (TF) |

| Zhang et al[14], 2014 | F | 50 | 6 | Head | CT: A solid well-vascularized tumor, with multiple liver metastases | F | NM | Operation halted | 4 yr PO (TF) |

| Zhang et al[14], 2014 | M | 63 | 4 | Head | CT: Well-vascularized tumor | F | NM | Operation | 3 mo PO (TF) |

| Meng et al[15], 2015 | F | 54 | 3 × 2.5 | Head | US: An ill-defined hypoechoic mass, the blood flow signal was plentiful. CT: a poor-defined isodense mass, heterogeneous striking enhancement during the arterial phase, homogeneous marked enhancement during the venous phase | NF | NM | Operation | NM |

| Meng et al[15], 2015 | F | 41 | 4 × 4 | Head | US: A well-demarcated hypoechoic mass, some blood flow signal was seen. CT: a poor-defined mass with low and heterogeneous density, marked enhancement | NF | NM | Operation | NM |

| Misumi et al[16], 2015 | F | 47 | 1.5 × 1.2 | Head | US: A low-echoic tumor, CT: A well demarcated tumor, strongly enhanced in the arterial phase and still faintly enhanced in the portal vein phase. Feeding artery from the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery and the draining vein into the portal vein. no dilation of either biliary or pancreatic ducts | NF | Pan-NEN | PD | 1 yr PO (TF) |

| Ginesu et al[17], 2016 | M | 55 | 1.3 | Uncinate process | CT: Arterial phase hypervascularity and slow wash-out | NF | Pan-NEN | PPPD | 2 yr PO (TF) |

| Tulumuru et al[18], 2016 | F | 62 | 2.8 × 2.8 × 2.7 | Body | CT: Well-defined margin and avid homogeneous enhancement. No lymphadenopathy or metastasis | NF | Pan-NEN | DP | 1 yr PO (TF) |

| Lin et al[1], 2016 | F | 42 | 5.2 × 6.3 | Body | CT: Marked enhancement in the arterial phase, distal pancreatic duct dilation | NF | Pan-NEN | CP | 1 yr PO (TF) |

| Furcea et al[19], 2017 | F | 53 | 3.5 × 2.5 × 2.5 | Isthmus | US: Encapsulated hypoechoic, inhomogeneous tumor. CEUS: intense arterial enhancement, rich arterial vascularization | NF | Pan-NEN | CP | NM |

| Nonaka et al[20], 2017 | F | 68 | 2.2 × 2.2 × 1.7 | Head | EUS: Low-echoic nodule. No dilation of either biliary or pancreatic ducts. CT: enhanced during the arterial phase, weakly enhanced during the portal phase | NF | NM | PPPD | 1 yr PO (TF) |

An asymptomatic 41-year-old Tibetan man was referred to our hospital in January 2020 with a pancreatic tumor incidentally detected on computed tomography (CT).

The patient underwent a chest CT scan at a local medical institution because of chest tightness. Although no obvious abnormality was found in the chest, a space-occupying lesion was incidentally found in the pancreas, and the patient was referred to our hospital for further treatment.

The patient’s medical history was unremarkable. He had not been previously diagnosed with hyperparathyroidism or pituitary adenoma (to exclude the possibility of MEN-1 related disease).

There was no family history of cancer.

There were no specific positive findings during physical examination.

Routine laboratory test results on admission, including routine blood test results, coagulation test results, and levels of blood glucose, liver function, renal function, and serum tumor markers [carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), alpha-fetoprotein, carbohydrate antigen (CA) 12-5, CA 19-9, CA 15-3, and CA72-4], were within normal ranges.

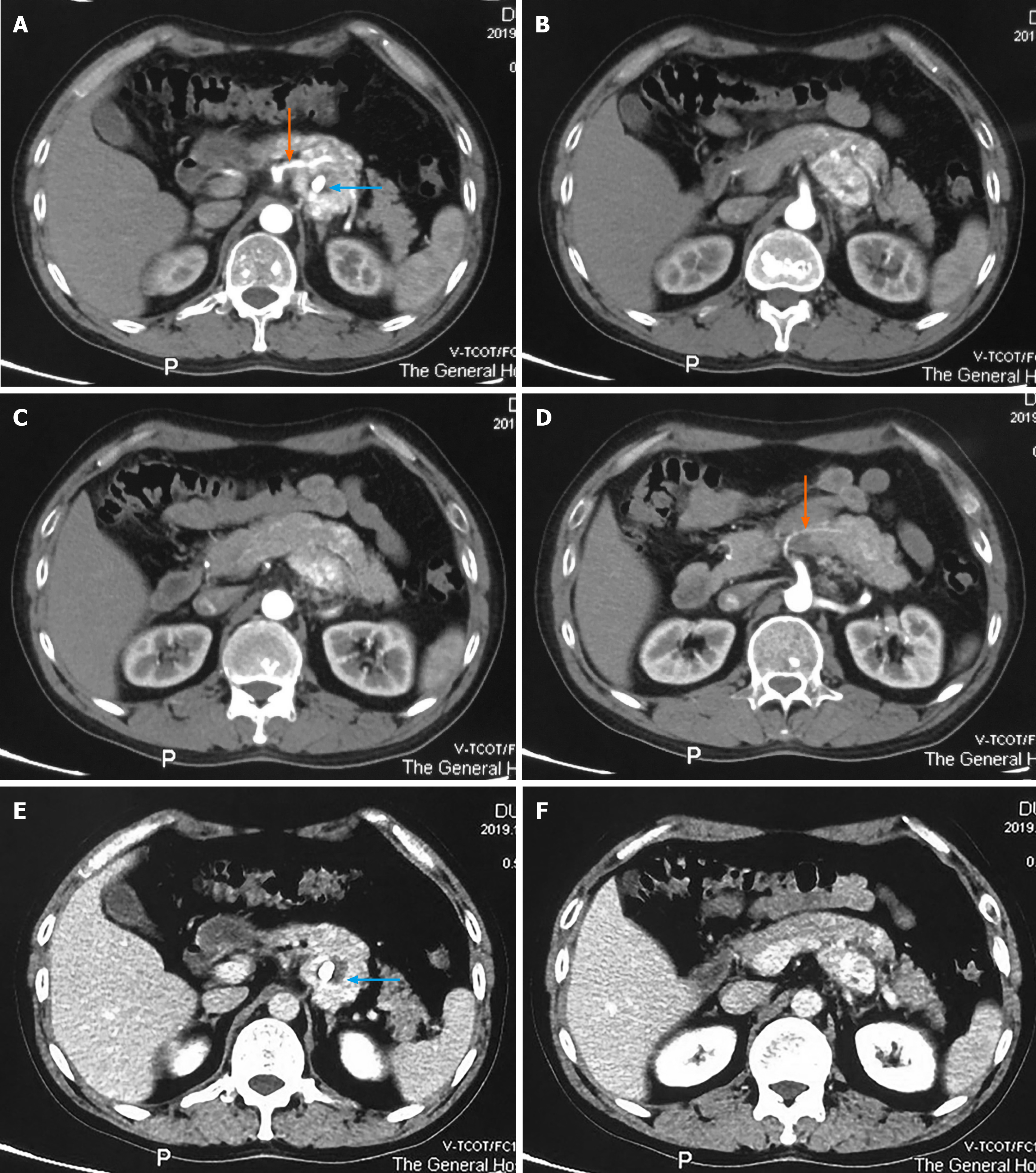

An abdominal CT scan revealed a 4.0 cm × 3.9 cm solid, heterogeneous soft tissue dense tumor behind the pancreatic body, and nodular calcification was also discovered. During the arterial phase, the tumor showed marked enhancement (Figure 1A-D), which was maintained, to a certain degree, during the venous phase (Figure 1E and F). Tumor enhancement was similar to that in the pancreas, and the tumor was not clearly demarcated from the adjacent pancreas, suggesting a pancreatic origin. The tumor was hypervascularized and supplied by a branch of the superior mesenteric artery (Figure 1A and D, orange arrows).

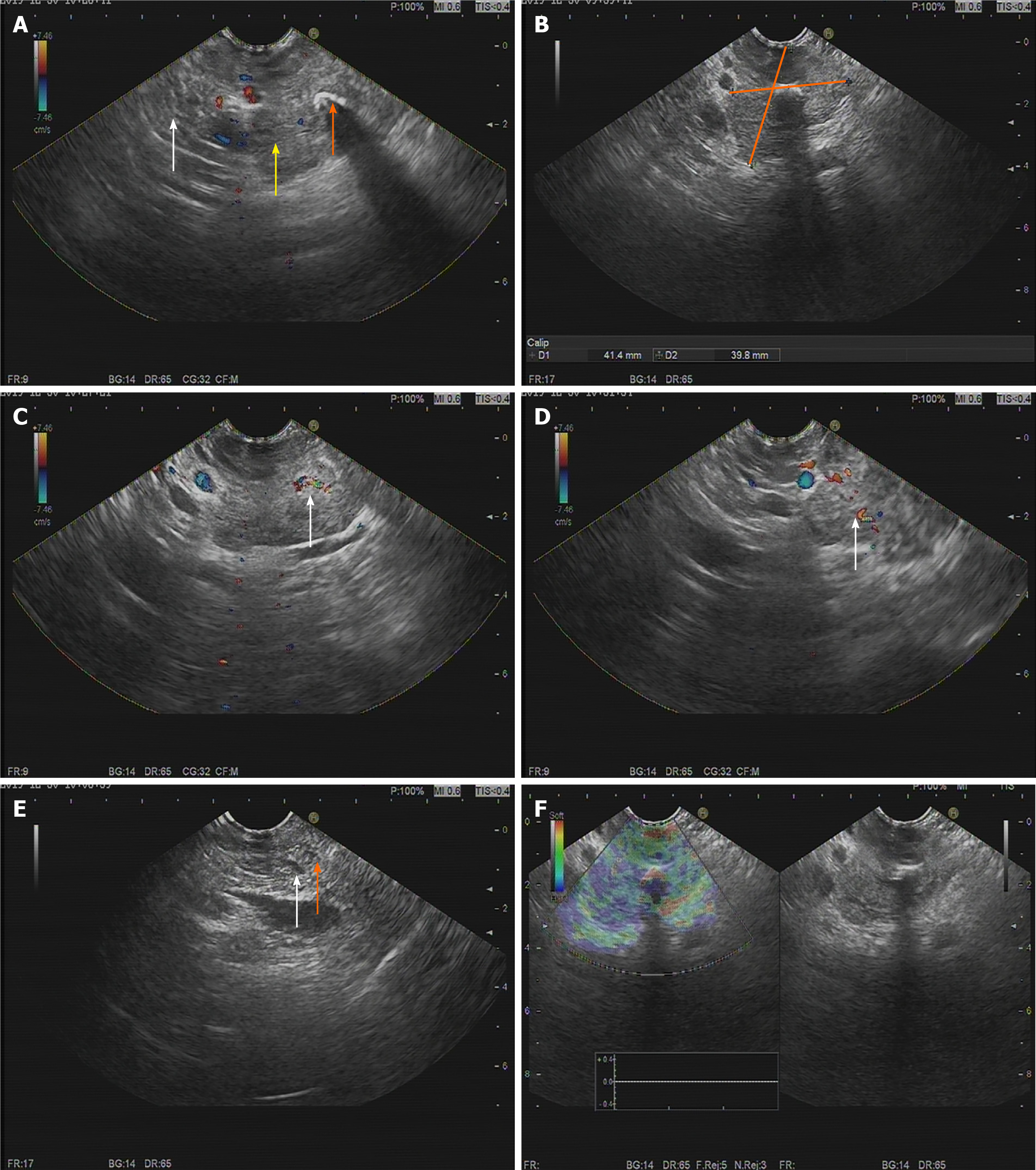

To further define the lesion, endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) was performed. EUS showed a 41.4 mm × 39.8 mm hypoechoic para-pancreatic solid mass with a modest blood flow signal. The tumor had an obscure boundary with the pancreas, and both the bile duct and pancreatic duct showed no dilation (Figure 2). Pathological examination by EUS-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) identified scattered glandular epithelial cells with slight pleomorphism, and malignancy could not be excluded.

Based on preoperative imaging features and EUS-guided FNA findings, a provisional diagnosis of pancreatic NEN (pan-NEN) was made.

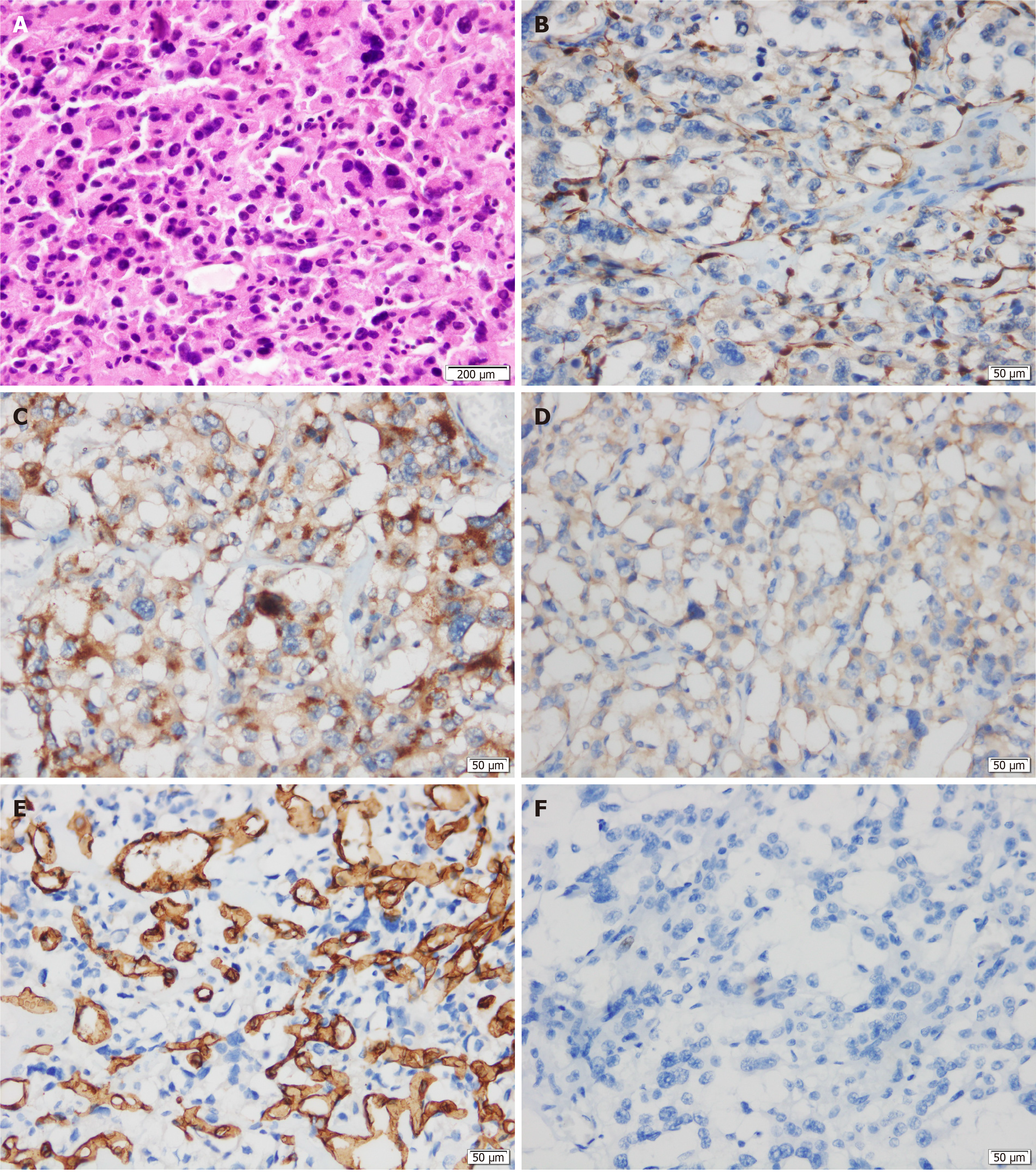

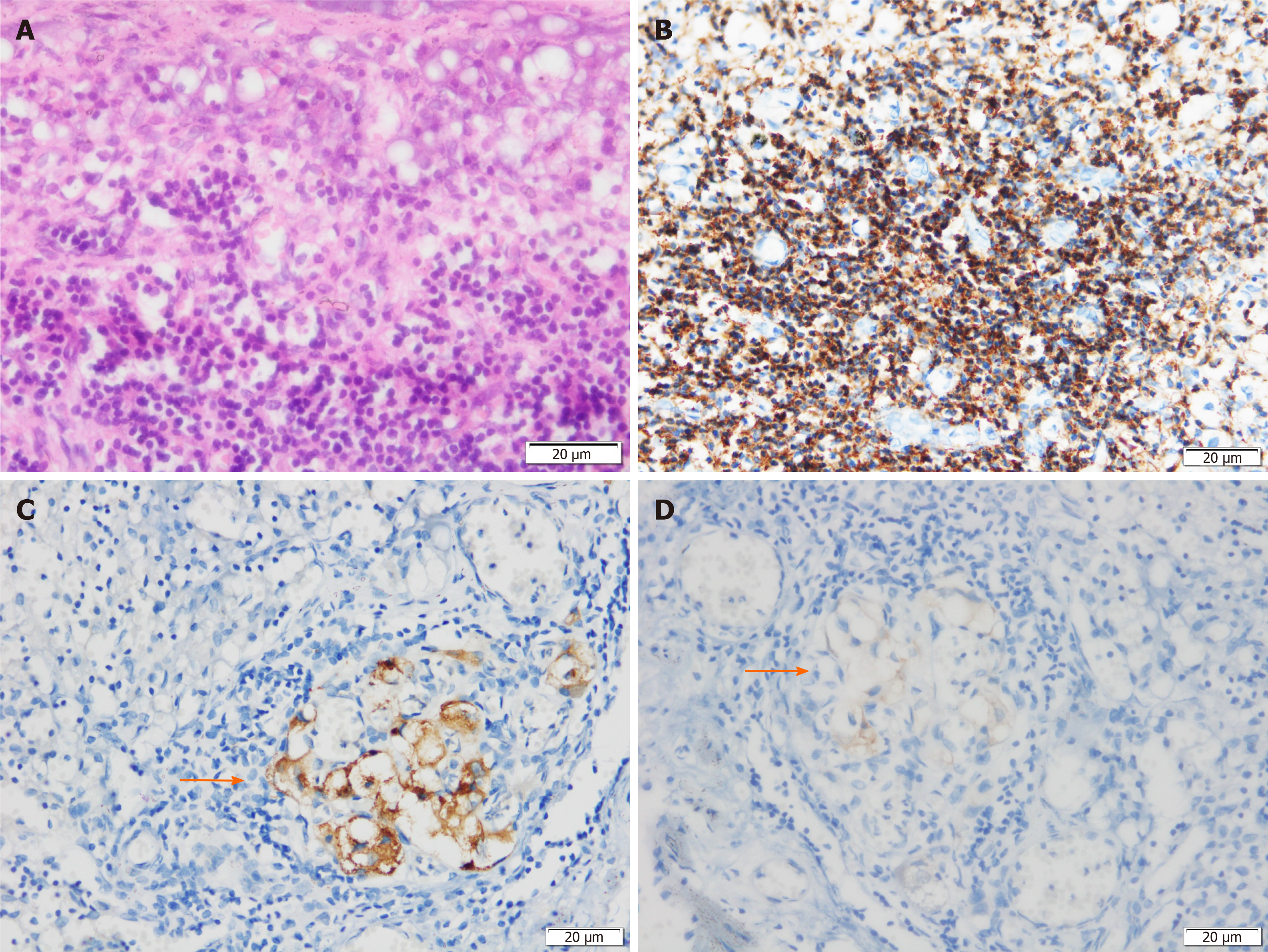

Histological examination showed that the neoplastic chief cells were arranged in a nest-like pattern, the cytoplasm was eosinophilic on hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining, the cell nest bulks were separated by capillary fibrous septa, forming the classic Zellballen pattern, and large and irregular cell nests were also observed (Figure 3A). Immunohistochemical analysis showed that the sustentacular cells in tumor tissue were positive for S-100 protein (Figure 3B), the neoplastic cells were positive for chromogranin A (CgA) (Figure 3C) and synaptophysin (Syn) (Figure 3D) but negative for cytokeratin (CK), and the surrounding fibrous septa were positive for CD34 (vascular endothelial cells, +, Figure 3E). The Ki-67 index was 2%, and no mitoses was observed (Figure 3F). Two of the eight resected pancreatic draining lymph nodes showed evidence of metastasis (Figure 4). The resection margin was free of residual tumor. Thus, combined with the histological and immunohistochemical features, a diagnosis of primary pancreatic paraganglioma with lymph node metastasis was established. Based on the pathological characteristics of the specimen and the non-functioning nature of the tumor, applying the Grading of Adrenal Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma scoring system[22], the case was considered to have a total score of 3 points, indicating that this was an intermediate risk case from the perspective of risk stratification.

On the basis of these findings, the patient underwent surgery. During the operation, a soft texture tumor was confirmed to originate from the posterior aspect of the pancreatic body, with massive tortuous veins distributed on the surface of the tumor, and no blood pressure fluctuation occurred when the tumor was palpated. Distal pancreatectomy (DP) was then performed, and the proximal pancreas including the tumor was transected using a linear stapler. The tumor was embedded in the body of the pancreas and was 4.1 cm × 4.2 cm in size. Intraoperative frozen section examination suggested the specimen to be a type of pan-NEN, malignancy could not be excluded, and dissection of superior/inferior pancreatic lymph nodes and celiac lymph nodes was performed. The resected specimens were sent for assessment based on the paraffin sections. The patient recovered well and no complications occurred.

The patient was safely discharged 11 d after surgery. A contrast-enhanced CT scan was performed during the follow-up period and the patient has remained disease-free for 1 year. The patient had a positive attitude towards the doctors’ treatment decisions. Follow-up of this patient is ongoing.

Extra-adrenal paraganglia are roughly symmetrically distributed in the body extending from the base of the skull to the pelvic floor, and this dispersed neuroendocrine system can be divided into two categories: Paraganglia related to parasympathetic nerves and those associated with sympathetic nerves. The former mainly includes jugulotympanic paraganglia, vagal paraganglia, carotid body paraganglia, and aorticopulmonary paraganglia, which are located at the base of the skull, neck, and anterior mediastinum; the latter is predominantly distributed along the sympathetic trunk of the posterior mediastinum and in the retroperitoneal cavity of the thoracolumbar paravertebral region. In addition, a small fraction of paraganglia can be found in the viscera such as the lungs, gallbladder, and urinary bladder[4].

Paragangliomas that arise from the adrenal medulla are referred to as pheochromocytomas, which are the most common type of paraganglioma[23]. The majority of extra-adrenal paragangliomas tend to originate in the middle ear, jugular foramen, carotid body, aorticopulmonary region, posterior mediastinum, and para-aortic region (especially Zuckerkandl’s body)[4]. Primary paragangliomas derived from the pancreas are particularly rare, and according to our comprehensive literature review, only 19 cases have been reported worldwide from 1998 till today[1,5-20]. Three patients showed evidence of lymph node metastasis[10,11,20] or invasion of vascular and peripancreatic adipose tissue[20], and one patient showed multiple liver metastases[14]. All treatments mentioned in the literature involved surgical resection. None of the retrieved studies proposed a systematic postoperative adjuvant therapy. Other reported cases did not originate from the pancreas but were probably the extension of a retroperitoneal paraganglioma that compressed the pancreas extrinsically, or were derived from ectopic paraganglia, which simulated a pancreatic mass.

It is difficult to accurately diagnose pancreatic paraganglioma preoperatively, especially when the tumor is non-functioning. Most patients were admitted with the chief complaint of abdominal pain or discomfort, or a pancreatic mass was incidentally found on an abdominal CT scan or on color Doppler ultrasonography (US)[15-18]. A few patients presented to the hospital with a history of hypertension, headache, and palpitation[14]. Unlike other pancreatic carcinomas, pancreatic paragangliomas rarely cause obvious dilatation of the biliary duct and obstructive jaundice even if the tumor is located in the head of the pancreas, but the pancreatic duct sometimes dilates to varying degrees[7,9,16]. An upper abdominal mass can occasionally be palpated during physical examination. Transabdominal US and contrast-enhanced CT are recommended as the routine imaging examinations. The lesion usually presents as a hypoechoic and inhomogeneous mass on US, and a rich blood signal can be detected on color Doppler flow imaging[8,12,15,19]. On contrast-enhanced ultrasound, the contrast agent is intensely captured by the mass in the early arterial phase, indicating rich arterial vascularization of the tumor[19]. Abdominal CT scanning often reveals a heterogeneous solid or cyst-solid soft tissue dense mass with a well-defined boundary[9,12,16]. Tumor location has been reported throughout the pancreas with the pancreatic head being the most common site. CT images of pancreatic paragangliomas have common features; the parenchyma of the mass shows marked enhancement in the arterial phase and still maintains a degree of enhancement in the venous phase[16,17,20]. However, these imaging features are not specific to pancreatic paragangliomas as they share similar characteristics with other types of pan-NENs, but can be distinguished from other pancreatic carcinomas which generally show poor enhancement in contrast-enhanced sequences. Furthermore, to make differential diagnosis, it is important to perform magnetic resonance imaging, because CT scans cannot distinguish pan-NENs from other types of hypervascular tumors, such as metastatic carcinoma or pancreatic cystadenoma[24].

Almost all patients with pancreatic paragangliomas show negative results for serum tumor markers such as CA 19-9, CA 12-5, and CEA. Because of the hypervascular nature of paragangliomas, aspiration biopsy can lead to significant bleeding[25], and biopsy may not necessarily capture tumor cells or tissue from the lesion, which may probably result in a negative finding and also implicitly increase the difficulty of diagnosis. Thus, the final diagnosis of paraganglioma based on postoperative histopathological and immunohistochemical examinations is more reliable. Following hematoxylin-eosin staining, the neoplastic chief cells are scattered or organ-like arranged, forming the classic Zellballen pattern, which is the most typical morphological pattern observed in paraganglioma. These nest-like structures may vary in size, and the neoplastic chief cell cytoplasm is eosinophilic and appears to have fine granules; nuclear pleomorphism and hyperchromatic nuclei can be obvious. The tumor cell nests are separated by vascularized fibrous septa, and the rich vascular structure can be clearly demonstrated by immunostaining for the endothelial cell marker CD34. Immunohistochemical staining with an anti-S-100 antibody can show the sustentacular cell network. Additionally, immunohistochemical results of the markers CgA, Syn, and neuro-specific enolase were also positive, but negative for CK. However, the basis of histopathological and immunohistochemical findings does not well define the diagnostic criteria for malignant paraganglioma, and it is generally thought that malignant behavior is associated with evidence of local invasion or metastasis[4,10]. To our knowledge, including the present case, malignant pancreatic paragangliomas account for 20% (4/20) of all cases.

To date, there is no therapeutic consensus for pancreatic paragangliomas, and surgical resection is the first treatment choice in most reports. The choice of operation depends on the tumor location in the pancreas, and tumors in the head or uncinate process of the pancreas can be treated by pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) or pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (PPPD); for cases with tumors located in the body or tail of the pancreas, local resection or DP can be chosen. The duration of postoperative follow-up reported in the literature ranges from 3 mo to 6 years, and all patients seemed to have an optimal prognosis and were tumor-free at the time of follow-up. Al-Jiffry et al[11] reported a case of malignant extra-adrenal pancreatic paraganglioma who remained disease-free for 36 mo after PD. Nonaka et al[20], who performed PPPD in a pancreatic paraganglioma patient harboring lymph node metastasis, reported that the patient was disease-free at the 12-mo follow-up examination. In our case, the patient underwent a successful radical resection and remained disease-free for more than 12 mo after the operation. Therefore, surgery may have a curative effect in patients with pancreatic paragangliomas with lymph node metastasis. However, due to the relatively short follow-up period, further verification is required.

Postoperative multimodal therapy may be necessary for pancreatic paragangliomas. High-dose [(131)I]-metaiodobenzylguanidine([(131I)]-MIBG) (492 mCi to 1160 mCi) has been verified to be effective in the management of metastatic paraganglioma, resulting in an overall complete response plus partial response rate of 22%[26]. Somatostatin analogs (SAs) such as octreotide, pasireotide, and lanreotide have been recommended for advanced pan-NENs and have demonstrated therapeutic benefits[27]. Although SAs have unknown effectiveness in patients with pancreatic paraganglioma, they may be a potential treatment for paraganglioma patients with positive SA receptors[28].

The present case report describes a rare primary paraganglioma arising in the body of the pancreas with lymph node metastasis and discusses the clinical presentation, diagnostic methods, and therapeutic options at full length. Definite diagnosis of pancreatic paraganglioma mainly depends on postoperative histopathological and immunohistochemical examinations, and DP with pancreatic draining lymph node dissection for such cases may achieve a curative effect. However, further assessment is needed during a long-term follow-up.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: Lisotti A, Primadhi RA, Sato H, Singh I S-Editor: Liu M L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Lin S, Peng L, Huang S, Li Y, Xiao W. Primary pancreatic paraganglioma: a case report and literature review. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14:19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Duncan AW, Lack EE, Deck MF. Radiological evaluation of paragangliomas of the head and neck. Radiology. 1979;132:99-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Drucker EA, McLoud TC, Dedrick CG, Hilgenberg AD, Geller SC, Shepard JA. Mediastinal paraganglioma: radiologic evaluation of an unusual vascular tumor. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;148:521-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lee KY, Oh YW, Noh HJ, Lee YJ, Yong HS, Kang EY, Kim KA, Lee NJ. Extraadrenal paragangliomas of the body: imaging features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:492-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fujino Y, Nagata Y, Ogino K, Watahiki H, Ogawa H, Saitoh Y. Nonfunctional paraganglioma of the pancreas: report of a case. Surg Today. 1998;28:209-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Parithivel VS, Niazi M, Malhotra AK, Swaminathan K, Kaul A, Shah AK. Paraganglioma of the pancreas: literature review and case report. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:438-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ohkawara T, Naruse H, Takeda H, Asaka M. Primary paraganglioma of the head of pancreas: contribution of combinatorial image analyses to the diagnosis of disease. Intern Med. 2005;44:1195-1196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kim SY, Byun JH, Choi G, Yu E, Choi EK, Park SH, Lee MG. A case of primary paraganglioma that arose in the pancreas: the Color Doppler ultrasonography and dynamic CT features. Korean J Radiol. 2008;9 Suppl:S18-S21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | He J, Zhao F, Li H, Zhou K, Zhu B. Pancreatic paraganglioma: A case report of CT manifestations and literature review. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2011;1:41-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Higa B, Kapur U. Malignant paraganglioma of the pancreas. Pathology. 2012;44:53-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Al-Jiffry BO, Alnemary Y, Khayat SH, Haiba M, Hatem M. Malignant extra-adrenal pancreatic paraganglioma: case report and literature review. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Borgohain M, Gogoi G, Das D, Biswas M. Pancreatic paraganglioma: An extremely rare entity and crucial role of immunohistochemistry for diagnosis. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;17:917-919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Straka M, Soumarova R, Migrova M, Vojtek C. Pancreatic paraganglioma - a rare and dangerous entity. Vascular anatomy and impact on management. J Surg Case Rep. 2014;2014:rju074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zhang L, Liao Q, Hu Y, Zhao Y. Paraganglioma of the pancreas: a potentially functional and malignant tumor. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Meng L, Wang J, Fang SH. Primary pancreatic paraganglioma: a report of two cases and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:1036-1039. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Misumi Y, Fujisawa T, Hashimoto H, Kagawa K, Noie T, Chiba H, Horiuchi H, Harihara Y, Matsuhashi N. Pancreatic paraganglioma with draining vessels. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:9442-9447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ginesu GC, Barmina M, Paliogiannis P, Trombetta M, Cossu ML, Feo CF, Addis F, Porcu A. Nonfunctional paraganglioma of the head of the pancreas: A rare case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;28:81-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tumuluru S, Mellnick V, Doyle M, Goyal B. Pancreatic Paraganglioma: A Case Report. Case Rep Pancreat Cancer. 2016;2:79-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Furcea L, Mois E, Al Hajjar N, Seicean A, Badea R, Graur F. Pancreatic gangliocytic paraganglioma - CEUS appearance. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2017;26:336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Nonaka K, Matsuda Y, Okaniwa A, Kasajima A, Sasano H, Arai T. Pancreatic gangliocytic paraganglioma harboring lymph node metastasis: a case report and literature review. Diagn Pathol. 2017;12:57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lack EE, Cubilla AL, Woodruff JM. Paragangliomas of the head and neck region. A pathologic study of tumors from 71 patients. Hum Pathol. 1979;10:191-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kimura N, Takekoshi K, Naruse M. Risk Stratification on Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma from Laboratory and Clinical Medicine. J Clin Med. 2018;7:242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Abbasi A, Wakeman KM, Pillarisetty VG. Pancreatic paraganglioma mimicking pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor. Rare Tumors. 2020;12:2036361320982799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Nakamura H, Tanaka S, Miyanishi K, Kawano Y, Osuga T, Ishikawa K, Yoshida M, Ohnuma H, Murase K, Takada K, Yamaguchi H, Nagayama M, Kimura Y, Takemasa I, Kato J. A case of hypervascular tumors in the liver and pancreas: synchronous hepatocellular carcinoma and pancreatic metastasis from renal cell carcinoma 36 years after nephrectomy. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9:932-937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Liew SH, Leong AS, Tang HM. Tracheal paraganglioma: a case report with review of the literature. Cancer. 1981;47:1387-1393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gonias S, Goldsby R, Matthay KK, Hawkins R, Price D, Huberty J, Damon L, Linker C, Sznewajs A, Shiboski S, Fitzgerald P. Phase II study of high-dose [131I]metaiodobenzylguanidine therapy for patients with metastatic pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4162-4168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Eriksson B. New drugs in neuroendocrine tumors: rising of new therapeutic philosophies? Curr Opin Oncol. 2010;22:381-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Forrer F, Riedweg I, Maecke HR, Mueller-Brand J. Radiolabeled DOTATOC in patients with advanced paraganglioma and pheochromocytoma. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;52:334-340. [PubMed] |