Published online Jan 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i1.54

Peer-review started: October 19, 2019

First decision: November 11, 2019

Revised: December 9, 2019

Accepted: December 14, 2019

Article in press: December 14, 2019

Published online: January 6, 2020

Processing time: 79 Days and 13.8 Hours

Distant metastasis, particularly visceral metastasis (VM), represents an important negative prognostic factor for prostate cancer (PCa) patients. However, due to the lower rate of occurrence of VM, studies on these patients are relatively rare. Consequently, studies focusing on prognostic factors associated with PCa patients with VM are highly desirable.

To investigate the prognostic factors for overall survival (OS) in PCa patients with lung, brain, and liver metastases, respectively, and evaluate the impact of site-specific and number-specific VM on OS.

Data on PCa patients with VM were extracted from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database between 2010 and 2015. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were used to analyze the association between clinicopathological characteristics and survival of patients with different site-specific VM. Kaplan-Meier analyses and Log-rank tests were performed to analyze the differences among the groups.

A total of 1358 PCa patients with site-specific VM were identified from 2010 to 2015. Older age (> 70 years) (P < 0.001), higher stage (T3/T4) (P = 0.004), and higher Gleason score (> 8) (P < 0.001) were found to be significant independent prognostic factors associated with poor OS in PCa patients with lung metastases. Higher stage (T3/T4) (P = 0.047) was noted to be the only independent risk factor affecting OS in PCa patients with brain metastases. Older age (> 70 years) (P = 0.010) and higher Gleason score (> 8) (P = 0.001) were associated with shorter OS in PCa patients with liver metastases. PCa patients with isolated lung metastases exhibited significantly better survival outcomes compared with PCa patients with other single sites of VM (P < 0.001). PCa patients with a single site of VM exhibited a superior OS compared with PCa patients with multiple sites of VM (P < 0.001).

This is the first Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-based study to determine prognostic factors affecting OS in PCa patients with different site-specific VM. Clinical assessments of these crucial prognostic factors become necessary before establishing a treatment strategy for these patients with metastatic PCa.

Core tip: Our study was the first Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-based study to determine prognostic factors affecting overall survival in prostate cancer (PCa) patients with different site-specific visceral metastases. For PCa patients with lung metastases, older age, advanced T stage, and higher Gleason score were independent prognostic factors for overall survival. For PCa patients with liver metastases, older age and higher Gleason score were the significant independent prognostic factors affecting survival rates, while only the advanced T stage was found to be an independent prognostic factor for PCa patients with brain metastases in our study.

- Citation: Cui PF, Cong XF, Gao F, Yin JX, Niu ZR, Zhao SC, Liu ZL. Prognostic factors for overall survival in prostate cancer patients with different site-specific visceral metastases: A study of 1358 patients. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(1): 54-67

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i1/54.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i1.54

Prostate cancer (PCa) represents the second most frequently diagnosed malignancy with an estimated 1.3 million new cases diagnosed and the fifth leading cause of cancer death in men with 359000 associated deaths worldwide in 2018[1]. For the majority of men with localized PCa, the five-year survival rate is almost 100% following standard treatment of radical prostatectomy[2,3]. However, in 17% of patients with localized disease, development of advanced metastatic disease is inevitable, and 20%-30% of metastatic cases develop visceral metastases (VM)[4-7]. Distant metastasis, particularly VM, represents an important negative prognostic factor, which results in reduced health-related quality of life and a significant increase in cancer-related mortality[6,8-11]. Accumulating evidence suggests that the incidence rates of newly diagnosed metastatic PCa have significantly increased, which is becoming a severe public health concern in the USA[12-14]. While, overall, the most frequent sites for metastatic PCa are bone and regional lymph nodes, dissemination to the lung, brain, and liver may also occur[15]. Notably, studies have revealed evidence for important differences in the survival rate between patients with VM and bone or lymph metastases[16]. Thus, the knowledge of the sites of metastases becomes crucial to investigate appropriate treatments and assess prognosis for PCa patients. However, due to the lower rate of occurrence of VM, studies on those patients are relatively rare. Consequently, studies focusing on prognostic factors associated with PCa with VM are highly desirable.

Using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, the present study aimed to identify the independent prognostic factors for PCa patients with specific sites of VM. This study also evaluated the impact of site-specific and number-specific VM on the survival of PCa patients with metastatic PCa. Furthermore, we also described the distribution of visceral metastatic sites in patients with PCa.

For the present study, the data were obtained from the SEER program of the USA National Cancer Institute, which consists of a consortium of 18 regional cancer registries with accurate and consistent data collection and contains representative cancer statistics from an estimated 28% of the American population. SEER is an authentic source of population-based information on cancer incidence and survival in the United States since 1973. The SEER registries routinely collect data on patient demographics and clinicopathological characteristics including primary tumor site, morphology, and stage at diagnosis; first course of treatment; and follow-up for vital status. Moreover, cancer data are updated to capture vital status, survival time, and cause of death. Follow-up interval in the original seven tumor registries of SEER now exceeds 40 years.

As the detailed information about distant metastatic sites was not available before 2010, therefore, we identified and collected data of all the PCa patients with VM diagnosed between 2010 and 2015.

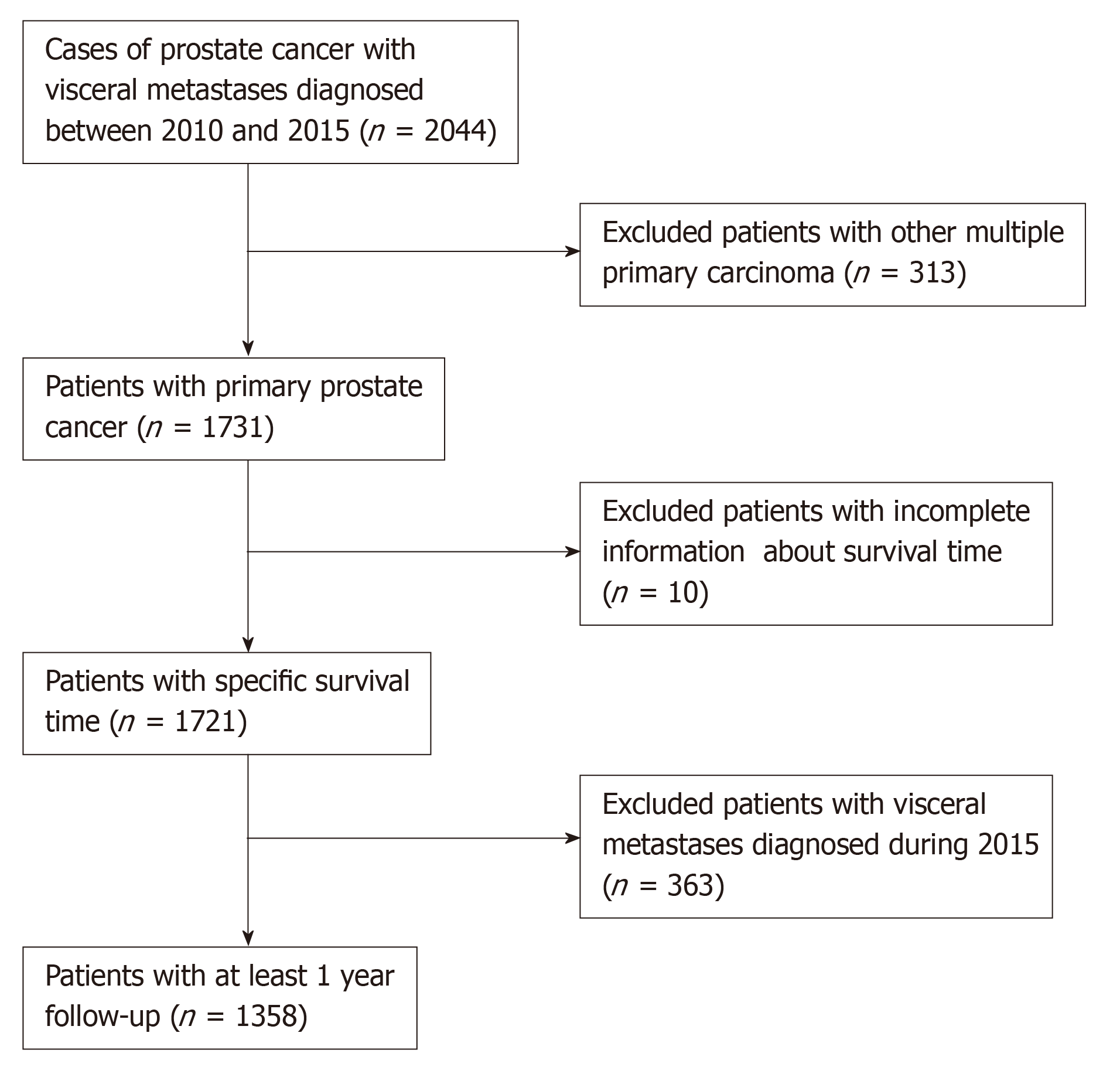

Eventually, a total of 1385 eligible patients were included in this study after exclusion of patients based on the criteria (Figure 1). The clinical characteristics included age at diagnosis (≤70 and >70 years old), race (Black, White, and other), marital status (married and unmarried), tumor grade (well-differentiated/moderately and poorly differentiated/undifferentiated), T stage (T1/T2 and T3/T4), N stage (N0 and N1), prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level (≤10 and >10 ng/mL), Gleason score (GS) (≤8 and >8), bone metastases (BM) (no and yes), site of VM (lung, brain, and liver), number of visceral sites involved (1 and >1). The unknown clinical data were categorized as an unknown category.

The primary endpoint of the study was prognostic factors. We investigated independent prognostic factors for PCa patients with different sites of VM and different numbers of visceral metastatic sites. We also evaluated the overall survival (OS) as the secondary endpoint of the study. Survival time was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of death from any cause, death from PCa, or the last follow-up. The impact of covariates including site-specific metastatic anatomical sites and number of visceral metastatic sites on OS was also evaluated.

The demographic and clinicopathological characteristics of the study population and frequency distributions of the metastatic sites were recorded. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the significant differences between the survival curves were assessed by the Log-rank test. Independent variables were first analyzed using univariate analysis. Significantly associated variables identified by univariate analysis were then entered into a Cox proportional hazards regression model for multivariate analysis, yielding hazard ratios (HR). Two-sided P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA 15.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) and SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). All data were extracted using SEER*Stat Software version 8.3.5 (Information Management Sercives, Inc. Calverton, MD, USA).

Overall, a total of 1358 patients with PCa meeting the eligibility criteria were included in the study. Table 1 presents the demographic and clinicopathological characteristics of PCa patients with VM. Of all the patients included, 981 (72.2%) had been married, 962 (70.8%) were Whites, 665 (49.0%) had undifferentiated or poorly differentiated PCa, 1021 (75.2%) exhibited elevated serum PSA levels of more than 10 ng/mL, and 1071 (78.9%) had BM.

| Variable | n (%) | |

| Marital status | Married | 981 (72.2) |

| Never married | 303 (22.3) | |

| Unknown | 74 (5.4) | |

| Age (yr) | ≤ 70 | 698 (51.4) |

| > 70 | 660 (48.6) | |

| Race | Black | 305 (22.5) |

| White | 962 (70.8) | |

| Other | 87 (6.4) | |

| Unknown | 4 (0.3) | |

| Grade | I/II | 52 (3.8) |

| III/IV | 665 (49.0) | |

| Unknown | 641 (47.2) | |

| T stage | T1/T2 | 520 (38.3) |

| T3/T4 | 344 (25.3) | |

| Unknown | 494 (36.4) | |

| N stage | N0 | 586 (43.2) |

| N1 | 442 (32.5) | |

| Unknown | 330 (24.3) | |

| PSA (ng/mL) | ≤ 10 | 136 (10.0) |

| > 10 | 1021 (75.2) | |

| Unknown | 201 (14.8) | |

| Gleason score | ≤ 8 | 307 (22.6) |

| 9 | 280 (20.6) | |

| 10 | 76 (5.6) | |

| Unknown | 695 (51.2) | |

| Bone metastases | No | 280 (20.6) |

| Yes | 1071 (78.9) | |

| Unknown | 7 (0.5) | |

| Number of metastatic sites | 1 | 1154 (85.0) |

| > 1 | 204 (15.0) | |

Table 2 depicts the pattern of VM for patients with PCa. A total of 1579 visceral sites were identified in the 1358 patients. The majority of patients exhibited lung metastases (n = 932, 59.0%), followed by liver (n = 507, 32.1%) and brain metastases (n = 140, 8.9%). Regarding the number of metastatic sites, 1154 (85.0%) patients had a single visceral metastasis, 187 (13.8%) had metastasis at different two sites including lung + brain (1.8%), lung + liver (11.6%), and liver + brain (0.4%), and 17 (1.2%) had metastasis at three different sites.

| Number of sites of visceral metastases | n |

| One | 1154 |

| Lung | 733 |

| Brain | 94 |

| Liver | 327 |

| Two | 187 |

| Lung + Brain | 24 |

| Lung + Liver | 158 |

| Liver + Brain | 5 |

| Three | 17 |

| Lung + Brain + Liver | 17 |

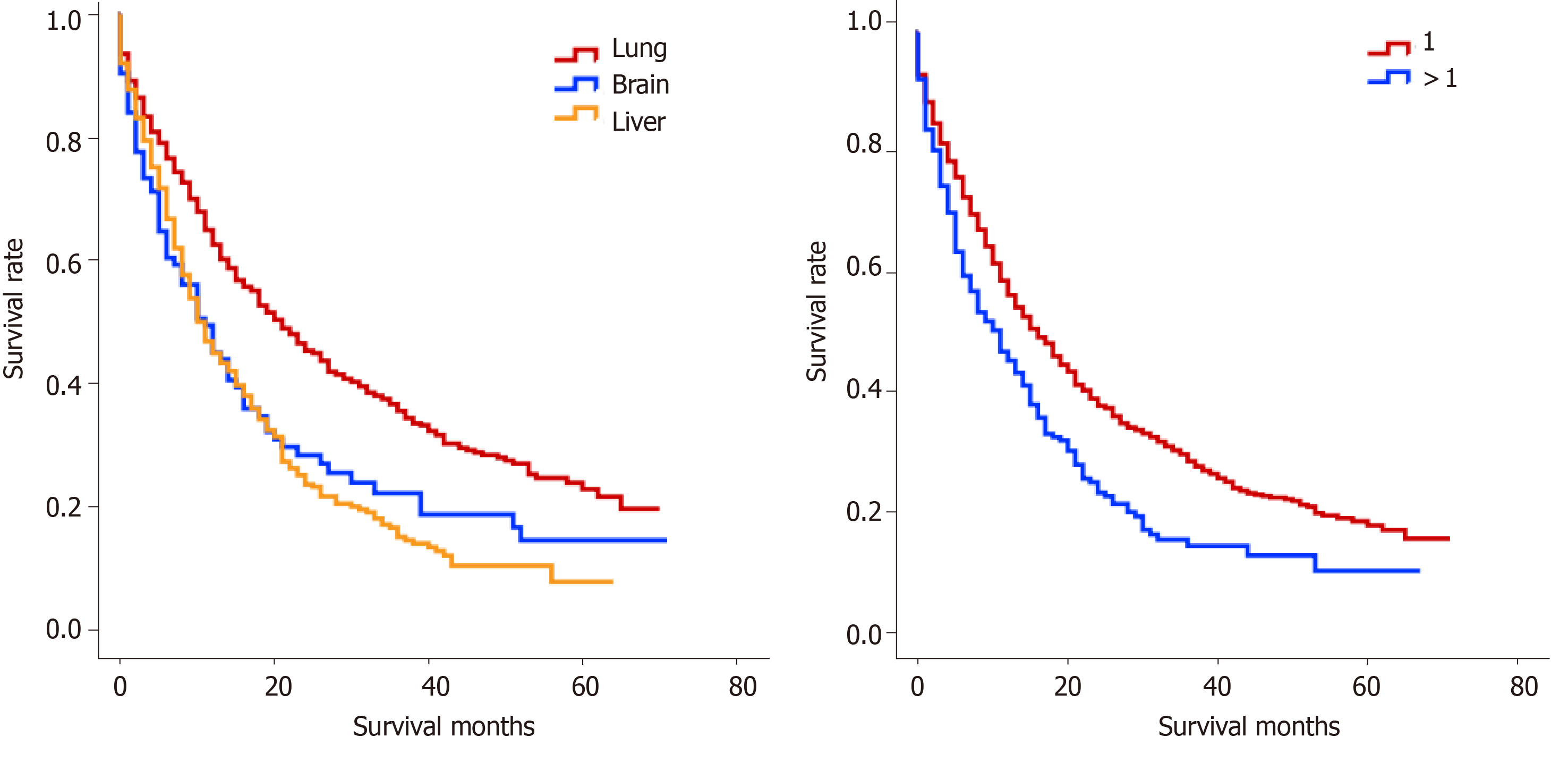

For PCa patients with a single site of VM, the median OS of patients with lung, brain, and liver metastases was 16 mo, 10 mo, and 10 mo, respectively (P < 0.001, Figure 2A). Moreover, the median OS of PCa patients with a single site of VM (14 mo) was significantly longer than that of PCa patients with multiple sites of VM (10 mo) (P < 0.001, Figure 2B).

Univariate Cox analysis for PCa patients with only one site of VM showed that age, grade, T stage, GS, BM, and the site of VM were significantly associated with OS (Table 3). However, for PCa patients with multiple sites of VM, age, T stage, and GS were significantly correlated with the survival time (Table 4). Overall, the univariate Cox model of the entire cohort indicated that age, grade, T stage, GS, BM, and the number of visceral metastatic sites were significantly associated with OS (Table 5).

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multiple analysis | ||||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | Ref. | |||||

| Never married | 1.030 | 0.873-1.215 | 0.726 | |||

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Age (yr) | ||||||

| ≤ 70 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| > 70 | 1.557 | 1.353-1.792 | < 0.001 | 1.593 | 1.265-2.007 | < 0.001 |

| Race | ||||||

| Black | Ref. | |||||

| White | 1.140 | 0.963-1.351 | 0.129 | |||

| Other | 0.788 | 0.565-1.100 | 0.162 | |||

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Grade1 | ||||||

| I/II | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| III/IV | 1.577 | 1.005-2.473 | 0.047 | 1.125 | 0.642-1.973 | 0.681 |

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| T stage | ||||||

| T1/T2 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| T3/T4 | 1.239 | 1.034-1.486 | 0.020 | 1.025 | 0.799-1.314 | 0.849 |

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| N stage | ||||||

| N0 | Ref. | |||||

| N1 | 1.162 | 0.988-1.368 | 0.070 | |||

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | |||

| PSA (ng/mL) | ||||||

| ≤ 10 | Ref. | |||||

| > 10 | 0.887 | 0.698-1.129 | 0.331 | |||

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Gleason score | ||||||

| ≤ 8 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| > 8 | 1.736 | 1.401-2.151 | < 0.001 | 1.609 | 1.260-2.055 | < 0.001 |

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Bone metastases | ||||||

| No | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Yes | 1.282 | 1.071-1.534 | 0.007 | 1.406 | 1.053-1.877 | 0.021 |

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Lung | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Brain | 1.548 | 1.209-1.983 | 0.001 | 1.257 | 0.778-2.029 | 0.350 |

| Liver | 1.682 | 1.444-1.959 | < 0.001 | 1.857 | 1.460-2.361 | < 0.001 |

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | Ref. | |||||

| Never married | 0.817 | 0.536-1.246 | 0.348 | |||

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Age (yr) | ||||||

| ≤ 70 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| > 70 | 1.545 | 1.137-2.101 | 0.005 | 2.354 | 1.337-4.145 | 0.003 |

| Race | ||||||

| Black | Ref. | |||||

| White | 0.964 | 0.649-1.430 | 0.855 | |||

| Other | 1.178 | 0.577-2.406 | 0.653 | |||

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Grade1 | ||||||

| I/II | Ref. | |||||

| III/IV | 1.607 | 0.587-4.399 | 0.356 | |||

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | |||

| T stage | ||||||

| T1/T2 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| T3/T4 | 2.127 | 1.410-3.208 | < 0.001 | 2.086 | 1.203-3.617 | 0.009 |

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| N stage | ||||||

| N0 | Ref. | |||||

| N1 | 0.936 | 0.648-1.352 | 0.724 | |||

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | |||

| PSA (ng/mL) | ||||||

| ≤ 10 | Ref. | |||||

| > 10 | 0.763 | 0.496-1.173 | 0.218 | |||

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Gleason score | ||||||

| ≤ 8 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| > 8 | 1.713 | 1.073-2.735 | 0.024 | 2.203 | 1.243-3.905 | 0.007 |

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| No | Ref. | |||||

| Yes | 0.827 | 0.569-1.203 | 0.321 | |||

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | Ref. | |||||

| Never married | 0.984 | 0.844-1.147 | 0.838 | |||

| unknown | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Age (yr) | ||||||

| ≤ 70 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| > 70 | 1.543 | 1.358-1.753 | < 0.001 | 1.672 | 1.353-2.065 | < 0.001 |

| Race | ||||||

| Black | Ref. | |||||

| White | 1.130 | 0.967-1.320 | 0.125 | |||

| Other | 0.838 | 0.620-1.134 | 0.252 | |||

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Grade1 | ||||||

| I/II | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| III/IV | 1.586 | 1.052-2.392 | 0.028 | 1.158 | 0.695-1.927 | 0.573 |

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| T stage | ||||||

| T1/T2 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| T3/T4 | 1.352 | 1.147-1.594 | < 0.001 | 1.236 | 0.990-1.543 | 0.061 |

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| N stage | ||||||

| N0 | Ref. | |||||

| N1 | 1.143 | 0.985-1.327 | 0.078 | |||

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | |||

| PSA (ng/mL) | ||||||

| ≤ 10 | Ref. | |||||

| > 10 | 0.836 | 0.678-1.030 | 0.092 | |||

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Gleason score | ||||||

| ≤ 8 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| > 8 | 1.710 | 1.407-2.077 | < 0.001 | 1.636 | 1.308-2.047 | < 0.001 |

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Bone metastases | ||||||

| No | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Yes | 1.205 | 1.025-1.417 | 0.024 | 1.323 | 1.019-1.716 | 0.035 |

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 1 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| > 1 | 1.446 | 1.222-1.712 | < 0.001 | 1.850 | 1.396-2.451 | < 0.001 |

For PCa patients with a single site of VM, multivariate Cox analysis revealed that the site of VM was an independent risk factor for OS. As compared to PCa patients with lung metastases, PCa patients with metastases to the liver had a significantly poorer OS (HR = 1.857; 95%CI: 1.460-2.361; P < 0.001). Furthermore, age > 70 years old (HR = 1.593; 95%CI: 1.265-2.007; P < 0.001), GS > 8 (HR = 1.609; 95%CI: 1.260-2.055; P < 0.001), and BM (HR = 1.406; 95%CI: 1.053-1.877; P = 0.021) were found to be significant independent prognostic factors for poor OS (Table 3).

Multivariate Cox analysis for PCa patients with multiple sites of VM group revealed that age > 70 years old (HR = 2.354; 95%CI: 1.337-4.145; P = 0.003), T3/T4 stage, (HR = 2.086; 95%CI: 1.203-3.617; P = 0.009) and GS > 8 (HR = 2.203; 95%CI: 1.243-3.905; P = 0.007) were significantly associated with an inferior OS (Table 4).

However, multivariate Cox analysis for the entire cohort indicated that some metastatic sites were the only significant independent prognostic factor affecting OS. Furthermore, PCa patients with multiple sites of VM had a significantly worse survival compared with those with a single site of VM (HR = 1.850; 95%CI: 1.396–2.451; P < 0.0001). Moreover, older age (>70 years) (HR = 1.672; 95%CI: 1.353-2.065; P < 0.0001), higher GS (>8) (HR = 1.636; 95%CI: 1.308-2.047; P < 0.0001), and BM (HR = 1.323; 95%CI: 1.019-1.716; P = 0.035) were also found to be statistically significant independent prognostic factors for poor OS (Table 5).

For PCa patients with lung metastases, age, grade, T stage, GS, and BM were significantly associated with OS as revealed by univariate Cox regression analysis (Table 6), and multivariate Cox analysis indicated that older age (>70 years) (HR = 2.084; 95%CI: 1.601-2.712; P < 0.001), advanced T3/T4 stage (HR = 1.490; 95%CI: 1.135-1.958; P = 0.004), higher GS > 8 (HR = 1.735; 95%CI: 1.315-2.289; P < 0.001) were noticeably associated with a shorter OS (Table 7).

| Variable | Lung | Brain | Liver | ||||||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Married | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| Never married | 0.924 | 0.757-1.127 | 0.436 | 1.169 | 0.738-1.853 | 0.506 | 0.950 | 0.754-1.198 | 0.667 |

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Age (yr) | |||||||||

| ≤ 70 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| > 70 | 1.728 | 1.471-2.029 | < 0.001 | 1.502 | 1.025-2.202 | 0.037 | 1.349 | 1.111-1.637 | 0.003 |

| Race | |||||||||

| Black | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| White | 1.078 | 0.888-1.310 | 0.447 | 1.130 | 0.685-1.865 | 0.632 | 1.130 | 0.892-1.432 | 0.310 |

| Other | 0.824 | 0.572-1.187 | 0.299 | 1.562 | 0.652-3.741 | 0.317 | 0.923 | 0.568-1.499 | 0.745 |

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Grade1 | |||||||||

| I/II | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| III/IV | 2.063 | 1.098-3.877 | 0.024 | 2.416 | 0.741-7.874 | 0.144 | 1.332 | 0.788-2.253 | 0.284 |

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| T stage | |||||||||

| T1/T2 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| T3/T4 | 1.476 | 1.203-1.811 | < 0.001 | 1.786 | 1.015-3.145 | 0.044 | 1.318 | 1.033-1.681 | 0.026 |

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| N stage | |||||||||

| N0 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| N1 | 1.136 | 0.942-1.368 | 0.182 | 0.957 | 0.587-1.559 | 0.859 | 1.128 | 0.903-1.410 | 0.289 |

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| PSA (ng/mL) | |||||||||

| ≤ 10 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| > 10 | 0.779 | 0.603-1.005 | 0.055 | 1.506 | 0.752-3.017 | 0.248 | 0.781 | 0.581-1.049 | 0.101 |

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Gleason score | |||||||||

| ≤ 8 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| > 8 | 1.848 | 1.446-2.361 | < 0.001 | 1.322 | 0.661-2.643 | 0.430 | 1.533 | 1.154-2.036 | 0.003 |

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Bone metastases | |||||||||

| No | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 1.246 | 1.013-1.533 | 0.038 | 1.258 | 0.748-2.115 | 0.388 | 1.029 | 0.817-1.296 | 0.807 |

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Variable | Lung | Brain | Liver | ||||||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Age (yr) | |||||||||

| ≤ 70 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| > 70 | 2.084 | 1.601-2.712 | < 0.001 | 0.994 | 0.553-1.785 | 0.983 | 1.499 | 1.099-2.043 | 0.010 |

| Grade1 | |||||||||

| I/II | Ref. | ||||||||

| III/IV | 2.031 | 0.879-4.692 | 0.097 | ||||||

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | ||||||

| T stage | |||||||||

| T1/T2 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| T3/T4 | 1.490 | 1.135-1.958 | 0.004 | 1.785 | 1.007-3.163 | 0.047 | 1.021 | 0.737-1.414 | 0.900 |

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Gleason score | |||||||||

| ≤ 8 | Ref. | Ref. | |||||||

| > 8 | 1.735 | 1.315-2.289 | < 0.001 | 1.688 | 1.224-2.327 | 0.001 | |||

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Bone metastases | |||||||||

| No | Ref. | ||||||||

| Yes | 1.327 | 0.961-1.833 | 0.086 | ||||||

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | ||||||

With respect to PCa patients with brain metastases, univariate Cox analysis identified that age and T stage were significantly associated with OS (Table 6); however, only T stage (P = 0.047) was found to be an independent predictor of OS as revealed by multiple Cox regression analysis (Table 7).

As for PCa patients with liver metastases, univariate Cox analysis showed that older age, advanced T stage, and higher GS were significantly associated with a poor OS (Table 6); however, multivariate Cox analysis showed that older age and higher GS were significant independent prognostic factors for OS. Taken together, PCa patients who were more than 70 years old had a shorter survival time than younger patients (HR = 1.499; 95%CI: 1.099-2.043; P = 0.010), and PCa patients with a GS > 8 exhibited a worse survival outcomes compared to those with a GS ≤ 8 (HR = 1.688; 95%CI: 1.224-2.327; P = 0.001) (Table 7).

Metastasis is the predominant cause of most cancer-related mortality. The sub-groups of metastatic PCa include oligometastatic disease and widely disseminated cancer. The progression of these sub-groups follows different courses and different treatment strategies are implicated based on disease status. Notably, the criteria to distinguish metastatic volume are based primarily on the number of detectable lesions and sites of metastases[17]. Moreover, there was no general agreement on a standard definition of oligometastatic metastases in PCa; however, the essential principle of non-VM was universally acceptable[18,19]. Currently, extensive researches have focused on the identification of oligometastatic PCa. However, there is a paucity of studies investigating patients with VM, particularly the metastatic disease detected at first diagnosis. Using this population-based study, we aimed to investigate the distribution of different patterns of metastases and evaluate the relationship between patterns of metastases and OS in PCa with VM, to provide valuable prognostic data to be beneficial to clinicians. Our analysis suggested that the location of VM and the number of metastatic sites were independent prognostic factors affecting OS for PCa patients with VM. Notably, the study also identified independent prognostic factors for patients with different sites of VM (lung metastases, brain metastases, and liver metastases) and different numbers of visceral sites (1 site and >1 site).

This study revealed that the lung was the most common visceral metastatic site among patients with PCa, followed by the liver, while distant metastases to the brain were relatively infrequent; the distribution characteristics of the three site-specific metastases were similar to previous studies including an autopsy study[20-22]. It is worth mentioning that PCa patients with VM which were analyzed in this study were confirmed at initial diagnosis and the sample size of cases with VM was much larger than that of previously published studies. We also found that regardless of sites the disease metastasized to, the majority of patients exhibited only a single site metastasis, which is consistent with a previous study[18]. However, some studies presented conflicting results. A study with a small sample size, including six patients with hepatic metastases at initial diagnosis with metastatic PCa, suggested that liver metastases were a late complication in the progression of PCa[23]. Similarly, a report by McCutcheon et al[24] indicated that the cases of brain metastases from PCa were sporadic, and always invariably presented as part of late complications in patients with widespread metastases.

Furthermore, only a few studies had investigated the influence of the number of distant metastases on the survival of patients with PCa. Recently, Gandaglia et al[16] found that patients with single-site metastasis had a significantly longer OS and cancer-specific survival compared to those with multiple metastatic sites. Another study also found that patients with ≤ 5 metastatic lesions had significantly higher survival rates than those with more than 5 lesions[19]. Both of these studies demonstrated that there was a significant correlation between the number of metastatic lesions and the survival time of patients with PCa; however, these observations were obtained by evaluating the PCa patients with distant metastases, not the strictly VM. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the impact of the number of visceral metastatic sites on OS of patients with PCa. Overall, the findings of the present study indicated that PCa patients with single-site VM had a longer OS than PCa patients with multiple sites of VM.

Further, we also extended our analysis to evaluate the influence of the sites of VM on the OS of patients with PCa. Notably, the present study further confirmed that distant metastases to the liver and brain had a comparable survival time with a median OS of 10 mo, while metastases to the lung showed a significantly increased survival (16 mo) for PCa patients with VM. Over recent years, only fewer studies have examined the effect of distant metastatic sites on the survival of patients with PCa. In this context, Halabi et al[22] found that metastatic sites in men with metastatic castration-resistant PCa (mCRPC) were significantly associated with a poor survival rate. The study also showed that PCa patients with liver metastases exhibited the worst median OS, as compared to PCa patients with lung metastases (13.5 mo vs 19.4 mo, P < 0.05). Recently, Pond et al[11] retrospectively analyzed a TAX 327 phase 3 trial and concluded that PCa patients with liver metastases had a markedly shorter median OS than PCa patients with lung metastases (10.0 mo vs 14.4 mo, P < 0.05). Consistent with these findings, our data also indicated that liver metastases might be an independent risk factor for OS than lung metastases; however, no significant difference was observed in OS between PCa patients with liver and brain metastases. It is worth noting here that previous studies were mostly conducted on patients with mCRPC and not in patients presenting with metastatic disease at diagnosis. Pouessel et al[23] found that liver metastasis from PCa was usually related to the histological type of neuroendocrine differentiation, and it represented a negative risk factor in PCa, which was very prone to developing mCRPC and increased significantly hazard ratio for death.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is also the first study to investigate the prognostic risk factors for site-specific VM in patients with PCa. We found that older age (>70 years), advanced (T3/T4) stage, and higher GS (>8) could be critical independent factors to anticipate a reduced survival of patients with lung metastases. Interestingly, for PCa patients with liver metastases, older patients had a shorter survival rate than younger patients and PCa patients with a higher GS also exhibited a poor prognosis compared with PCa patients with a lower GS. For PCa patients with brain metastases, older age (>70 years) and advanced T3/T4 stage had statistical significance in univariate Cox analysis and Kaplan-Meier analysis; however, only T stage was found to be a significant independent predictor of OS in PCa patients with brain metastases by multiple Cox analysis. Therefore, clinicians must take into consideration these important risk factors and individualized treatments accordingly.

Furthermore, the present study also analyzed the prognostic risk factors for single-site metastasis and multiple sites of VM. For patients with single-site VM, our findings indicated that older age (>70 years), higher GS (>8), and BM could independently affect the survival of PCa patients with VM. Conversely, older age (>70 years), higher GS (>8), and advanced T3/T4 stage were independent unfavorable prognosis factors for patients with multiple sites of VM.

Importantly, we noted that the patient’s age contributed significantly to the OS of patients, as older age (>70 years) was an independent prognosis factor for PCa patients with different patterns of VM. Previously, the majority of studies have been dedicated to studying the association of age with PCa. Of note, Mandel et al[25] found that older patients (age ≥ 75 years) were more likely to exhibit a higher proportion of poor Gleason grade disease and most likely to present with invasive tumor compared with younger patients with PCa, and also demonstrated that older age (≥75 years) was independent risk factors for worse biochemical recurrence-free and metastasis-free survival. Another series of studies also confirmed that older patients were more commonly diagnosed with high-risk and advanced stage PCa[26,27]. The age-specific difference in risk classification may be explained by the low rate of PSA testing in older men[28], while other studies attributed the poor survival to inappropriate treatment strategies[29-31]. In the majority of cases, more active management was not provided to the patients with good performance status. Therefore, clinicians should articulate effective and rational medical management based on the overall status of older patients.

Moreover, we also found that lymph node status did not affect the OS of PCa patients with lung, brain, or liver metastases. A retrospective study on selected patients with newly diagnosed metastatic PCa from the STAMPEDE trial also found that there were significant differences in failure-free survival and OS between subgroups of patients with positive lymph node metastases and without lymph nodes involvement[32]. It was quite apparent that metastases to the lymph nodes always represented a strong prognostic factor in patients with PCa; however, it failed to predict survival for PCa patients with VM.

VM infrequently occur among patients with PCa. However, our study with a large sample size was a population-based assessment of the atypical metastases, which was the major advantage of this study compared to previous studies. However, there were several limitations to this study. First, the type of variables through the SEER database was limited, for example, limited data were available for change of PSA levels during the course of the disease, the sequence of treatments, type of treatments, and performance status, which might have a significant impact on survival rates. Second, our study was only focused on three major sites of VM (lung, brain, and liver); however, other metastatic sites have also been found to contribute significantly to the poor outcome of PCa. Third, techniques used for confirming the diagnosis of VM were unavailable. Moreover, as a retrospective study, inherent biases were inevitable.

In conclusion, the lung was the most frequent site of VM in a patient with PCa; however, PCa patients with lung metastases exhibited a better OS. Furthermore, patients with multiple sites of VM exhibited an inferior OS compared to patients with a single site of VM. For PCa patients with lung metastases, older age, advanced T stage, and higher GS were independent prognostic factors for OS. For PCa patients with liver metastases, older age and higher GS were the significant independent prognostic factors affecting survival rates, while only advanced T stage was found to be an independent prognostic factor for PCa patients with brain metastases in our study.

The present study is the first SEER-based study to determine prognostic factors affecting OS in PCa patients with different site-specific VM. Furthermore, this population-based study also demonstrated that site-specific VM exhibited differential effects on the survival of patients with metastatic PCa. Therefore, clinical assessments of these prognostic factors become necessary before establishing a treatment strategy for these patients with metastatic PCa.

Metastases to distant organs may significantly threaten quality of life and survival in men with prostate cancer (PCa). There is sufficient evidence to support that the incidence rates of newly diagnosed metastatic PCa have significantly increased, which is becoming a severe public health concern in the United States.

Bone is the most commonly involved organ in PCa, and substantial studies explore characteristics of PCa patients with liver metastases. However, due to the lower rate of occurrence of visceral metastases (VM), studies on those patients are relatively rare.

To identify the prognostic factors for overall survival (OS) in PCa patients with VM and evaluate the impact of site-specific and number-specific VM on OS.

The records of PCa patients with VM in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database, diagnosed between 2010 and 2015, were obtained. Cox regression analysis was used to identify the independent prognostic factors. Kaplan-Meier analyses and Log-rank tests were performed to analyze the differences among the groups.

Older age, higher stage, and higher Gleason score were found to be significant independent prognostic factors associated with a poor OS in PCa patients with lung metastases. Higher stage was noted to be the only independent risk factor affecting OS in PCa patients with brain metastases. Older age and higher Gleason score were associated with a shorter OS in PCa patients with liver metastases. PCa patients with isolated lung metastases exhibited significantly better survival outcomes compared with PCa patients with other single sites of VM. PCa patients with a single site of VM exhibited a superior OS compared with PCa patients with multiple sites of VM.

Our research identifies prognostic factors affecting OS in PCa patients with different site-specific VM. Patients with lung metastases or with a single site of VM have a better prognosis.

Special attention should be paid to those patients with poor factors. Clinical assessments of these crucial prognostic factors become necessary before establishing a treatment strategy for these patients with metastatic PCa. However, the type of accessible data through the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program is limited, and the relationship between other variables such as change of PSA levels during the course of the disease and survival need to be investigated.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited Manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Que J S-Editor: Wang YQ L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53206] [Cited by in RCA: 55838] [Article Influence: 7976.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (132)] |

| 2. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11573] [Cited by in RCA: 13167] [Article Influence: 1881.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 3. | Schymura MJ, Sun L, Percy-Laurry A. Prostate cancer collaborative stage data items--their definitions, quality, usage, and clinical implications: a review of SEER data for 2004-2010. Cancer. 2014;120 Suppl 23:3758-3770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Scosyrev E, Messing EM, Mohile S, Golijanin D, Wu G. Prostate cancer in the elderly: frequency of advanced disease at presentation and disease-specific mortality. Cancer. 2012;118:3062-3070. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR, Horti J, Pluzanska A, Chi KN, Oudard S, Théodore C, James ND, Turesson I, Rosenthal MA, Eisenberger MA; TAX 327 Investigators. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1502-1512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4284] [Cited by in RCA: 4356] [Article Influence: 207.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Goodman OB, Flaig TW, Molina A, Mulders PF, Fizazi K, Suttmann H, Li J, Kheoh T, de Bono JS, Scher HI. Exploratory analysis of the visceral disease subgroup in a phase III study of abiraterone acetate in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2014;17:34-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | de Bono JS, Oudard S, Ozguroglu M, Hansen S, Machiels JP, Kocak I, Gravis G, Bodrogi I, Mackenzie MJ, Shen L, Roessner M, Gupta S, Sartor AO; TROPIC Investigators. Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: a randomised open-label trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1147-1154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2344] [Cited by in RCA: 2423] [Article Influence: 161.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nørgaard M, Jensen AØ, Jacobsen JB, Cetin K, Fryzek JP, Sørensen HT. Skeletal related events, bone metastasis and survival of prostate cancer: a population based cohort study in Denmark (1999 to 2007). J Urol. 2010;184:162-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 253] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rigaud J, Tiguert R, Le Normand L, Karam G, Glemain P, Buzelin JM, Bouchot O. Prognostic value of bone scan in patients with metastatic prostate cancer treated initially with androgen deprivation therapy. J Urol. 2002;168:1423-1426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Armstrong AJ, Garrett-Mayer E, de Wit R, Tannock I, Eisenberger M. Prediction of survival following first-line chemotherapy in men with castration-resistant metastatic prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:203-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Pond GR, Sonpavde G, de Wit R, Eisenberger MA, Tannock IF, Armstrong AJ. The prognostic importance of metastatic site in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2014;65:3-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Doctor SM, Tsao CK, Godbold JH, Galsky MD, Oh WK. Is prostate cancer changing?: evolving patterns of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer. 2014;120:833-839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Weiner AB, Matulewicz RS, Eggener SE, Schaeffer EM. Increasing incidence of metastatic prostate cancer in the United States (2004-2013). Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2016;19:395-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hu JC, Nguyen P, Mao J, Halpern J, Shoag J, Wright JD, Sedrakyan A. Increase in Prostate Cancer Distant Metastases at Diagnosis in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:705-707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gandaglia G, Abdollah F, Schiffmann J, Trudeau V, Shariat SF, Kim SP, Perrotte P, Montorsi F, Briganti A, Trinh QD, Karakiewicz PI, Sun M. Distribution of metastatic sites in patients with prostate cancer: A population-based analysis. Prostate. 2014;74:210-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 244] [Cited by in RCA: 379] [Article Influence: 34.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gandaglia G, Karakiewicz PI, Briganti A, Passoni NM, Schiffmann J, Trudeau V, Graefen M, Montorsi F, Sun M. Impact of the Site of Metastases on Survival in Patients with Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol. 2015;68:325-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tosoian JJ, Gorin MA, Ross AE, Pienta KJ, Tran PT, Schaeffer EM. Oligometastatic prostate cancer: definitions, clinical outcomes, and treatment considerations. Nat Rev Urol. 2017;14:15-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 22.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sweeney CJ, Chen YH, Carducci M, Liu G, Jarrard DF, Eisenberger M, Wong YN, Hahn N, Kohli M, Cooney MM, Dreicer R, Vogelzang NJ, Picus J, Shevrin D, Hussain M, Garcia JA, DiPaola RS. Chemohormonal Therapy in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:737-746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1943] [Cited by in RCA: 2091] [Article Influence: 209.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Singh D, Yi WS, Brasacchio RA, Muhs AG, Smudzin T, Williams JP, Messing E, Okunieff P. Is there a favorable subset of patients with prostate cancer who develop oligometastases? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58:3-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bubendorf L, Schöpfer A, Wagner U, Sauter G, Moch H, Willi N, Gasser TC, Mihatsch MJ. Metastatic patterns of prostate cancer: an autopsy study of 1,589 patients. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:578-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1179] [Cited by in RCA: 1266] [Article Influence: 50.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (35)] |

| 21. | Vinjamoori AH, Jagannathan JP, Shinagare AB, Taplin ME, Oh WK, Van den Abbeele AD, Ramaiya NH. Atypical metastases from prostate cancer: 10-year experience at a single institution. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199:367-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Halabi S, Kelly WK, Ma H, Zhou H, Solomon NC, Fizazi K, Tangen CM, Rosenthal M, Petrylak DP, Hussain M, Vogelzang NJ, Thompson IM, Chi KN, de Bono J, Armstrong AJ, Eisenberger MA, Fandi A, Li S, Araujo JC, Logothetis CJ, Quinn DI, Morris MJ, Higano CS, Tannock IF, Small EJ. Meta-Analysis Evaluating the Impact of Site of Metastasis on Overall Survival in Men With Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1652-1659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in RCA: 347] [Article Influence: 38.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Pouessel D, Gallet B, Bibeau F, Avancès C, Iborra F, Sénesse P, Culine S. Liver metastases in prostate carcinoma: clinical characteristics and outcome. BJU Int. 2007;99:807-811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | McCutcheon IE, Eng DY, Logothetis CJ. Brain metastasis from prostate carcinoma: antemortem recognition and outcome after treatment. Cancer. 1999;86:2301-2311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Mandel P, Kriegmair MC, Kamphake JK, Chun FK, Graefen M, Huland H, Tilki D. Tumor Characteristics and Oncologic Outcome after Radical Prostatectomy in Men 75 Years Old or Older. J Urol. 2016;196:89-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Tosoian JJ, Alam R, Gergis C, Narang A, Radwan N, Robertson S, McNutt T, Ross AE, Song DY, DeWeese TL, Tran PT, Walsh PC. Unscreened older men diagnosed with prostate cancer are at increased risk of aggressive disease. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2017;20:193-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Delongchamps NB, Wang CY, Chandan V, Jones RF, Threatte G, Jumbelic M, de la Roza G, Haas GP. Pathological characteristics of prostate cancer in elderly men. J Urol. 2009;182:927-930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Cooperberg MR, Moul JW, Carroll PR. The changing face of prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8146-8151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 249] [Cited by in RCA: 249] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Droz JP, Albrand G, Gillessen S, Hughes S, Mottet N, Oudard S, Payne H, Puts M, Zulian G, Balducci L, Aapro M. Management of Prostate Cancer in Elderly Patients: Recommendations of a Task Force of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology. Eur Urol. 2017;72:521-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Droz JP, Aapro M, Balducci L, Boyle H, Van den Broeck T, Cathcart P, Dickinson L, Efstathiou E, Emberton M, Fitzpatrick JM, Heidenreich A, Hughes S, Joniau S, Kattan M, Mottet N, Oudard S, Payne H, Saad F, Sugihara T. Management of prostate cancer in older patients: updated recommendations of a working group of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e404-e414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Droz JP, Balducci L, Bolla M, Emberton M, Fitzpatrick JM, Joniau S, Kattan MW, Monfardini S, Moul JW, Naeim A, van Poppel H, Saad F, Sternberg CN. Management of prostate cancer in older men: recommendations of a working group of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology. BJU Int. 2010;106:462-469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | James ND, Spears MR, Clarke NW, Dearnaley DP, De Bono JS, Gale J, Hetherington J, Hoskin PJ, Jones RJ, Laing R, Lester JF, McLaren D, Parker CC, Parmar MKB, Ritchie AWS, Russell JM, Strebel RT, Thalmann GN, Mason MD, Sydes MR. Survival with Newly Diagnosed Metastatic Prostate Cancer in the "Docetaxel Era": Data from 917 Patients in the Control Arm of the STAMPEDE Trial (MRC PR08, CRUK/06/019). Eur Urol. 2015;67:1028-1038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 271] [Cited by in RCA: 309] [Article Influence: 28.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |