Copyright

©2011 Baishideng Publishing Group Co.

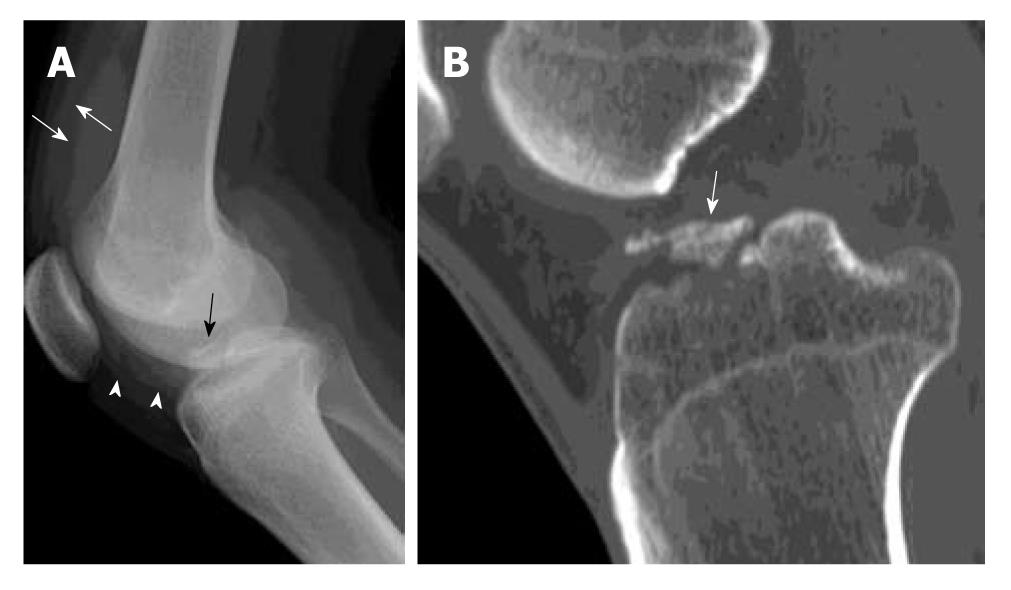

Figure 1 Avulsion fracture of tibial spine.

A 20-year-old man suffered knee injury during a football match. A: Lateral radiograph of the knee shows a displaced avulsion fracture of the anterior cruciate ligament (black arrow) at the anterior intercondylar eminence of tibia. The fracture fragment is completely elevated from the native bone. Increased soft tissue opacity in the suprapatellar pouch (white arrows) and infrapatellar pouch (white arrowheads) is in keeping with haemarthrosis; B: Reformatted sagittal computed tomography image of the same patient through the mid tibial plateau shows a displaced avulsion fracture of the tibial intercondylar eminence (white arrow).

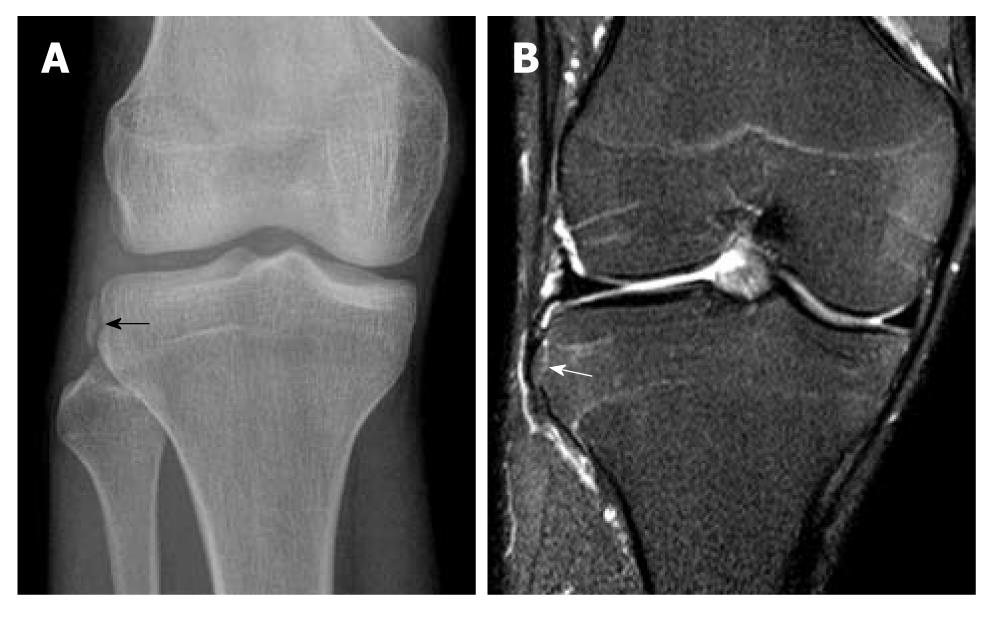

Figure 2 Segond fracture.

A 30-year-old man suffered knee injury during a basketball match. A: Frontal radiograph of the right knee shows an avulsion fracture fragment at the lateral tibial rim (black arrow) compatible with Segond fracture. This fracture is frequently associated with a torn anterior cruciate ligament which also happened in this patient (not shown); B: A coronal T2-weighted fat suppression magnetic resonance image of the same patient. Corresponding site reveals a minimally displaced Segond fracture (white arrow) which may be easily missed in this patient with no significant bone bruise or oedema.

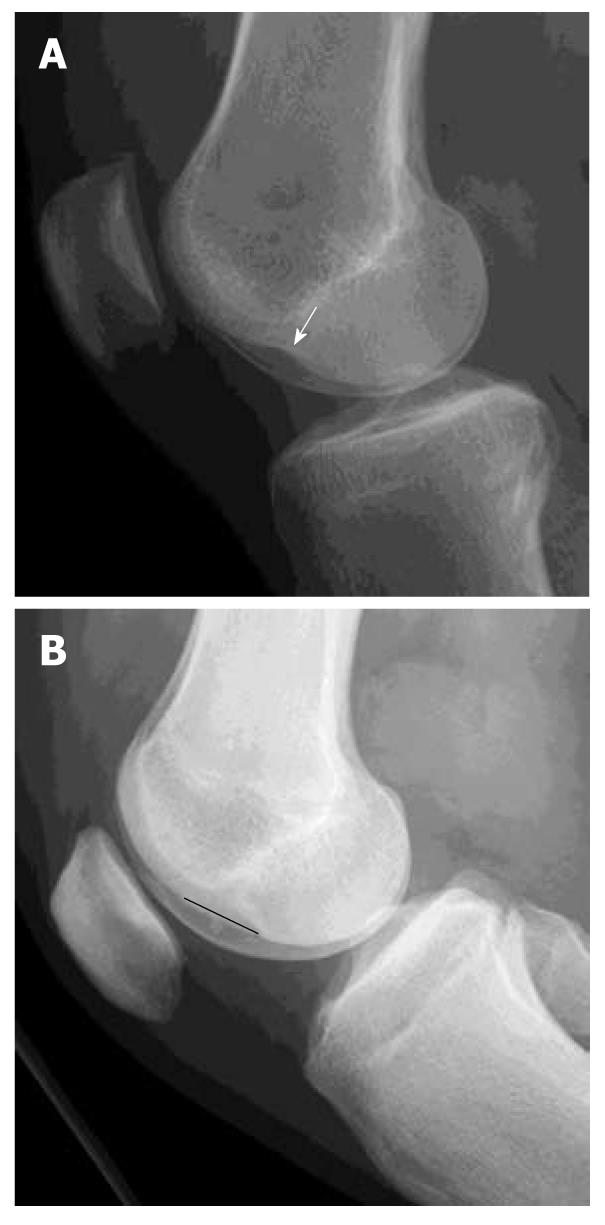

Figure 3 Osteochondral injury lateral femoral condyle.

Lateral radiographs of two patients with complete anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear. A: Deep notch sign is abnormal deepening of the condylofemoral sulcus larger than 1.5 mm (white arrow); B: Long notch sign is abnormal lengthening of the condylofemoral sulcus (black straight line). These two signs are suggestive of osteochondral fracture of the lateral femoral condyle and highly associated with ACL tear though these are not very common findings.

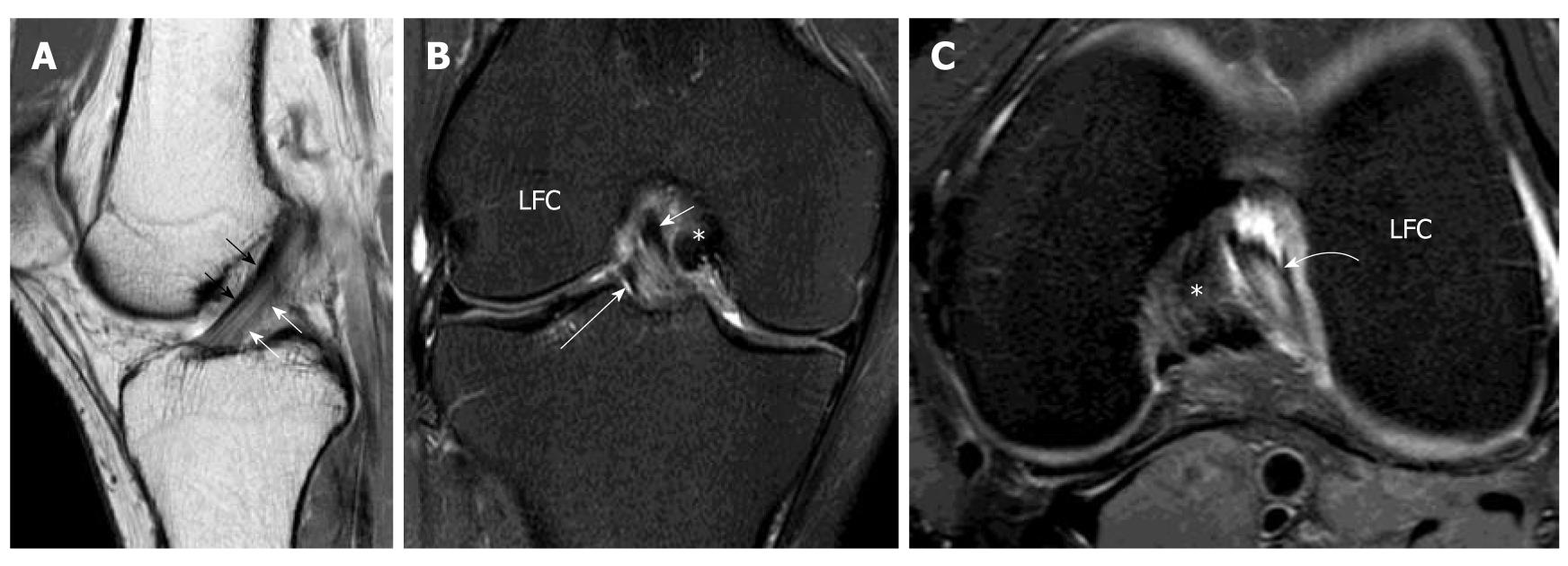

Figure 4 Normal anterior cruciate ligament.

Volunteer, 24-year-old man with no history of injury and clinical instability. Sagittal intermediate-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) of the knee. A: Demonstrates a normal anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) which is characterized by a taut, continuous, low signal intensity fibres extending from the tibial plateau anteriorly to the medial aspect of the lateral femoral condyle. The more anterior portion of ACL is the anteromedial (AM) bundle (black arrows) while the more posterior portion is posterolateral (PL) bundle (white arrows). They cannot be well delineated from each other on this sagittal image. The PL bundle shows higher signal intensity than AM bundle. Coronal T2-weighted fat suppression MR knee image; B: The mid and distal ACL in the intercondylar fossa. The fibres are running superiorly and laterally within the intercondylar fossa from tibial attachment to the lateral femoral condyle (LFC). The more medial portion is the AM bundle (white short arrow) while the lateral portion is the PL bundle (white long arrow). Axial intermediate-weighted fat suppression MR image; C: Normal mid substance of ACL (curved white arrow). The ACL is elliptical in appearance because it is running obliquely to the scan plane. The two bundles cannot be differentiated from each other. *: Posterior cruciate ligament.

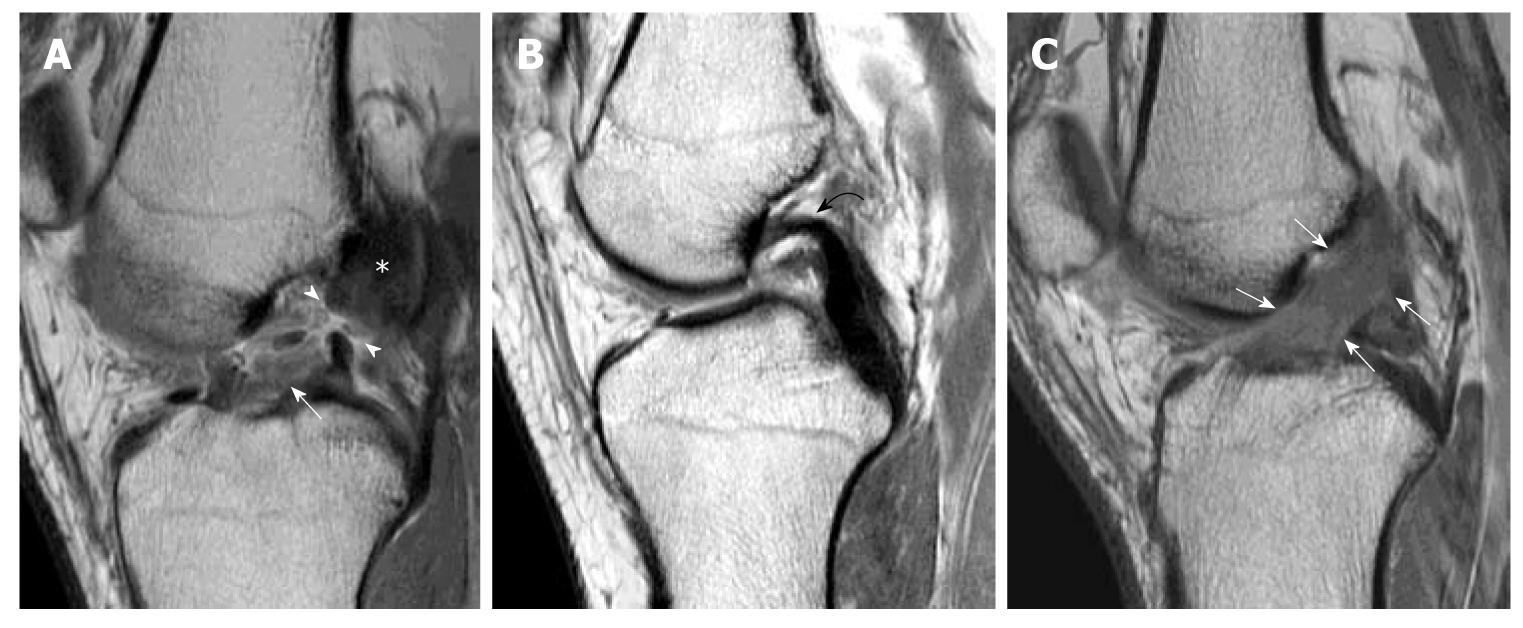

Figure 5 Primary signs of anterior cruciate ligament tear.

Sagittal intermediate-weighted images of three different patients showing different patterns of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear. A: Typical appearance of ACL tear at the mid-substance with fibres discontinuity of ACL (arrowheads). Residual stumps on femoral (asterisk) and tibial sides (white arrow) are lax, thickened and increased in signal intensity; B: Chronic ACL tear with absence of normal ACL fibres compatible with complete resorption of fibres. PCL (Curved black arrow); C: Acute high grade intrasubstance tear as characterized by thickening and oedematous change of ACL fibres which show increased signal intensity (white arrows). The fibres are still in continuity suggestive of partial ACL tear.

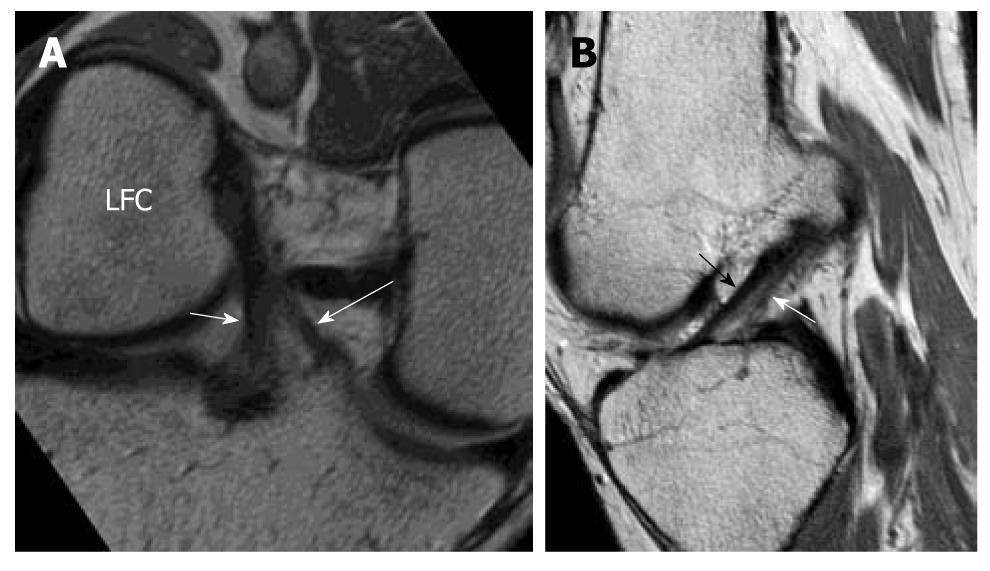

Figure 6 High resolution imaging normal anterior cruciate ligament in oblique coronal and oblique sagittal planes.

Volunteer of a 31-year-old man with no history of injury and clinical instability. Note that the AM bundle (white long arrow) and PL bundle (white short arrow) can be well depicted on the oblique coronal image at the tibial attachment but not at the femoral attachment and not by the oblique sagittal image.

Figure 7 High resolution imaging anterior cruciate ligament in oblique axial plane.

A: Oblique axial image can clearly delineate the two bundles and assess each bundle separately; AM bundle (long white arrow) PL bundle (short white arrow). B: Partial tear of the anterior cruciate ligament. Oblique axial image at the femoral side shows thickening and hyperintense signal intensity of the AM bundle (black long arrow) while fibres are absent in the region of the PL bundle (black short arrow). Features are compatible with high grade partial AM bundle tear and complete PL tear which were confirmed in arthroscopy. LFC: Lateral femoral condyle; *: Posterior cruciate ligament; F: Fibular head.

Figure 8 Partial tear of the anterior cruciate ligament.

Sagittal intermediate-weighted image of partial anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear. The ACL appears lax, concave in appearance (white arrow) and increased in signal intensity. However, the fibres are still in continuity suggestive of partial ACL tear.

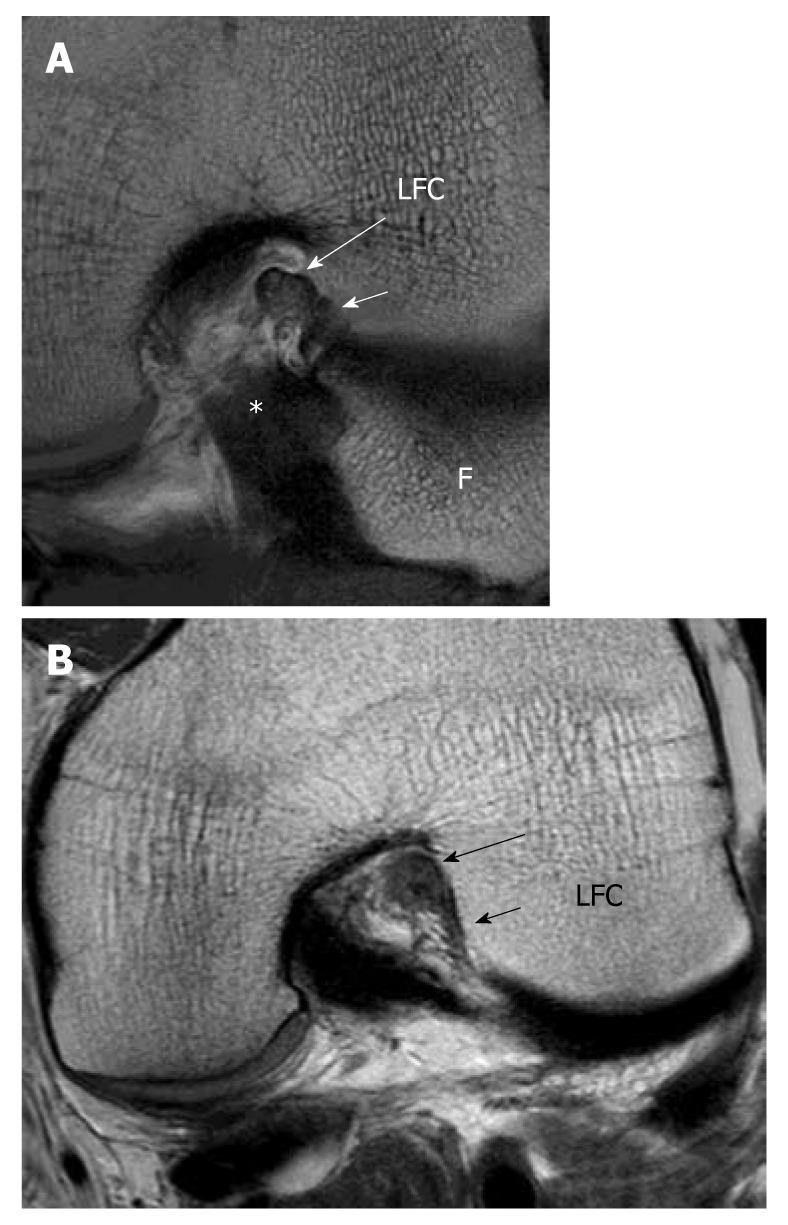

Figure 9 Magnetic resonance knee in partial flexion.

Volunteer, 31-year-old man with no history of injury and clinical instability. Sagittal intermediate-weighted magnetic resonance image in full extension. A: And 30 degree of knee flexion; B: Demonstrates the usefulness of knee flexion. When the knee is extended, sagittal image shows features suspicious of an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear. When the knee is flexed, a gap (black arrow) is clearly present confirming the presence of an ACL tear.

Figure 10 Bone bruises.

A 26-year-old man suffered knee injury. Sagittal T2-weighted fat suppression magnetic resonance knee image shows that there are bone rises (asterisks) present in the mid-lateral femoral condyle and posterolateral tibial plateau which indicate that the mechanism of injury is internal rotation of the tibia in valgus stress injury. This pattern of bone bruise has a high association of anterior cruciate ligament complete tear which is present in this patient (not shown).

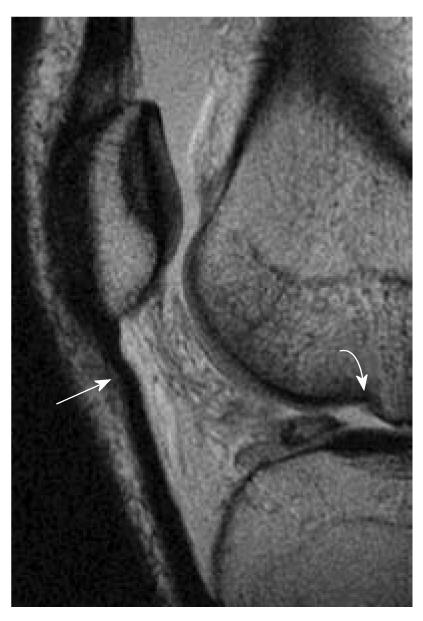

Figure 11 Patellar buckling sign and lateral femoral notch sign.

A 37-year-old man who suffered knee injury. Osteochondral injury and patellar buckling sign. Sagittal intermediate-weighted magnetic resonance image demonstrates a deep depression of the middle portion of the lateral femoral condyle (curved white arrow). Normal condylopatellar sulcus should be smaller than 1.5 mm. Notch depth between 1 and 2 mm is suggestive and over 2 mm is diagnostic of anterior cruciate ligament tear. Buckling of proximal patellar tendon (white arrow) also indicates the underlying anterior cruciate ligament tear.

Figure 12 Uncovered posterior horn lateral meniscus and anterior tibial translation.

A 32-year-old man who suffered knee injury. Sagittal intermediate-weighted magnetic resonance image of complete anterior cruciate ligament tear patient. The anterior displacement of the tibial translation is measured as the distance between two lines parallel to the picture frame (white lines). At the mid-sagittal plane of lateral femoral condyle, a line is drawn through the most posterior corner of the lateral tibial plateau, and the second line is tangent to the most posterior aspect of the lateral femoral condyle. Anterior tibial translation between 5 and 7 mm is suggestive and over 7 mm is diagnostic of anterior cruciate ligament tear. Note that the lateral meniscus also intersects the tangent to posterior margin of tibia and represents the uncovered posterior horn of lateral meniscus.

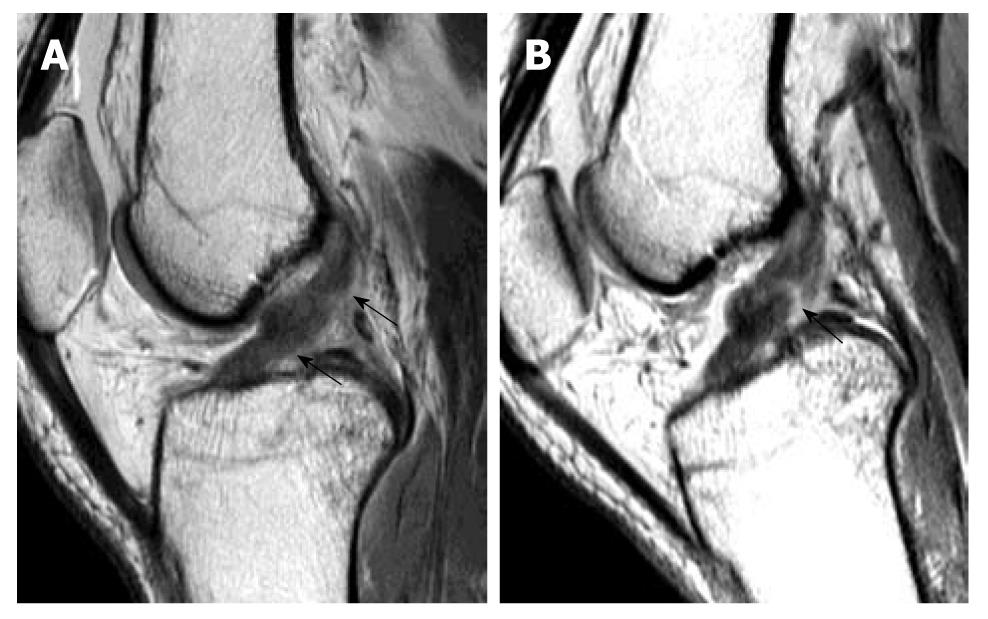

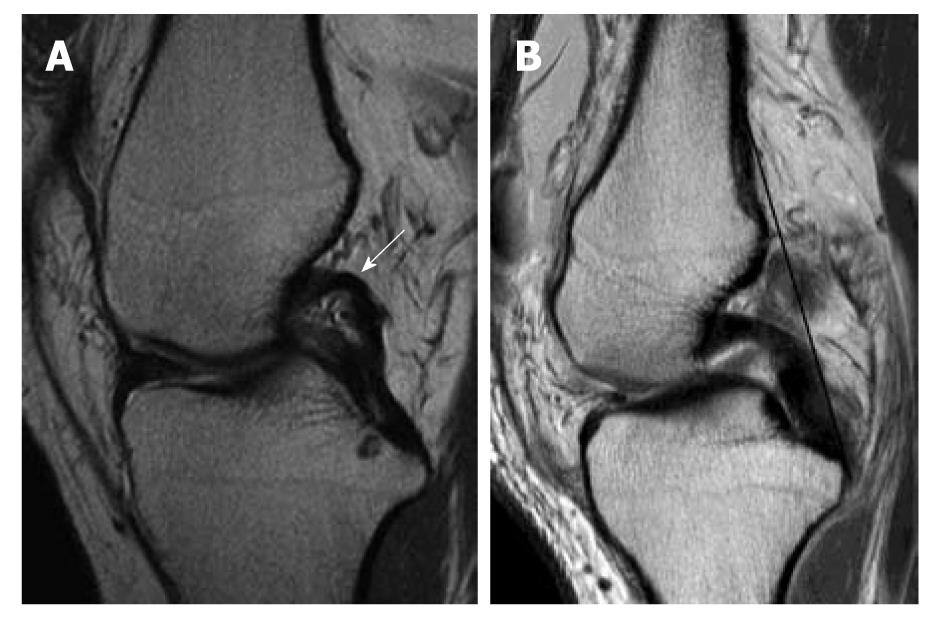

Figure 13 Posterior cruciate ligament buckling and Posterior cruciate ligament line sign.

Sagittal intermediate-weighted magnetic resonance knee image of a completely torn anterior cruciate ligament. A: Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) buckling sign. The PCL is considered to be hyperbuckled if any portion of its posterosuperior border is concave (white arrow); B: The PCL line sign. A line tangential to the posterior margin of the PCL is drawn (black line) and if this tangent does not intersect the posterior cortex of the femur within 5cm of its distal end, the PCL line is considered to be positive.

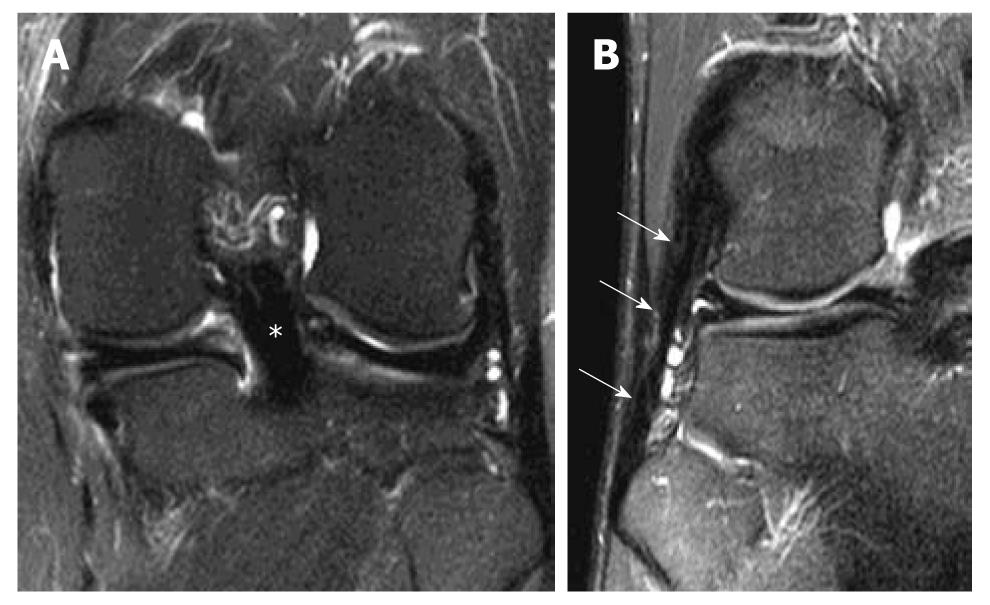

Figure 14 Coronal whole posterior cruciate ligament and lateral collateral ligament sign.

Coronal T2-weighted fat suppression magnetic resonance knee images of two different patients with complete anterior cruciate ligament tear show that A: The entire posterior cruciate ligament (*); B: Entire lateral collateral ligament (white arrows) can be seen in a single coronal image.

Figure 15 Shearing of fat pad.

Sagittal T2-weighted fat suppression magnetic resonance image shows a fracture of Hoffa’s fat pad that has isolated a segment of fat (white arrows).

Figure 16 Peripheral vertical tear in a patient with complete anterior cruciate ligament tear.

Sagittal intermediate-weighted magnetic resonance image demonstrates a peripheral vertical tear (white arrows) extending of the posterior horn of lateral meniscus. This kind of peripheral vertical tear can be easily missed and is frequently associated with anterior cruciate ligament tear.

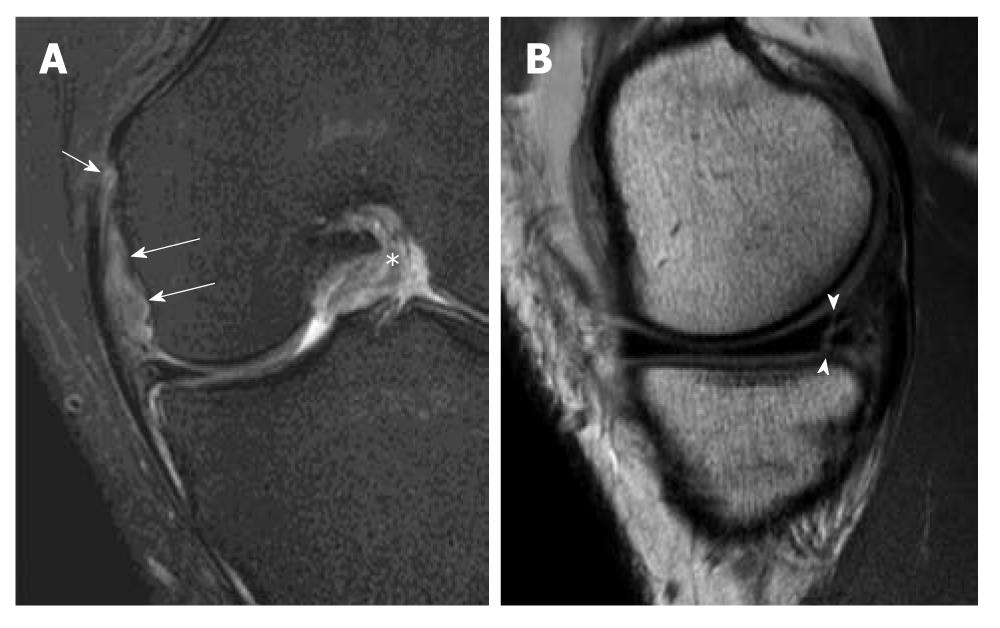

Figure 17 O’ Donoghue’s triad.

Magnetic resonance images of a patient with complete anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear showing O’ Donoghue’s triad. A: Coronal T2-weighted fat suppression magnetic resonance (MR) image demonstrates complete tear of the meniscofemoral ligament (white long arrows) and femoral attachment of the medial collateral ligament (white short arrow). Note that the ACL in the intercondylar fossa has a substantial tear (asterisk); B: Sagittal intermediate-weighted MR image shows an associated vertical and horizontal (complex) peripheral tear at the posterior horn of medial meniscus (arrowheads). These injuries constitute the classical “O Donoghue’s triad”.

Figure 18 Posterolateral corner injury.

A 25-year-old man suffered knee injury during a football match. A: Axial intermediate-weighted; B: Coronal T2-weighted fat suppression images of a patient with acute complete anterior cruciate ligament tear (white arrowhead). Oedema with thickening of the lateral collateral ligament and partial disruption of the fibres are present at the femoral origin (L). The posterior capsule and the oblique popliteal ligament (OPL) also show thickening and oedematous change. There is mild sprain of the femoral insertion of the popliteus tendon (P). The popliteofibular ligament is severely swollen and oedematous suggestive of high grade partial tear (curved black arrow).

Figure 19 Celery stalk sign (mucoid degeneration).

Sagittal intermediate-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) image. A: Enlargement of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) (white arrows) with increased signal intensity compatible with mucoid degeneration. Low-signal-intensity fibres running parallel to the long axis of high signal ACL i.e. celery stalk sign; B: Axial intermediate-weighted fat suppression MR image shows cystic change within the ACL (white arrows) predominantly in the PL bundle. LFC: Lateral femoral condyle.

Figure 20 Pericruciate ganglion cyst.

Sagittal intermediate-weighted MR image shows a ganglion cyst (white arrows) arising from proximal posterior half of ligament.

- Citation: Ng WHA, Griffith JF, Hung EHY, Paunipagar B, Law BKY, Yung PSH. Imaging of the anterior cruciate ligament. World J Orthop 2011; 2(8): 75-84

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v2/i8/75.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v2.i8.75