Published online Dec 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i36.11382

Peer-review started: August 21, 2021

First decision: September 12, 2021

Revised: September 22, 2021

Accepted: November 15, 2021

Article in press: November 15, 2021

Published online: December 26, 2021

Processing time: 123 Days and 23.8 Hours

Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPNs) are rare tumors of the pancreas. Typically, they occur in young females, often have characteristic imaging features, such as cystic components and calcification, and have few effects on the pancreatic duct.

A 31-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with the chief complaint of epigastric pain. There was only mild tenderness in his upper abdomen, and blood tests showed only a slight increase in alkaline phosphatase. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography showed a 40-mm-diameter, hypovascular mass in the head of the pancreas, and the main pancreatic duct upstream of the mass was severely dilated. Magnetic resonance imaging showed low intensity on T1-weighted images, with high intensity on T2-weighted image in some parts. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma was the primary differential diagnosis. Portal vein infiltration could not be ruled out, so this case was a candidate for neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Subsequently, endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration was performed, and pathological evaluation and immunostaining suggested a diagnosis of SPN. Thus, pancreatoduodenectomy was performed. One year after the operation, the patient is alive with no recurrence.

Main pancreatic duct dilatation is usually a finding of suspected pancreatic cancer. However, pancreatic duct dilatation can occur in SPN depending on the location and growth speed. Therefore, SPN should be considered in the differential diagnosis of tumors with pancreatic duct dilatation, and pathological evaluation by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration should be actively performed.

Core Tip: Main pancreatic duct dilatation is usually a suspected finding of pancreatic cancer. However, pancreatic duct dilatation can occur in solid pseudopapillary neoplasm (SPN) depending on the location and growth speed. Therefore, SPN should be considered as one of the differential diagnoses of tumors with pancreatic duct dilatation, and pathological evaluation by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration should be actively performed.

- Citation: Nakashima S, Sato Y, Imamura T, Hattori D, Tamura T, Koyama R, Sato J, Kobayashi Y, Hashimoto M. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas in a young male with main pancreatic duct dilatation: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(36): 11382-11391

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i36/11382.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i36.11382

Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPNs) are rare tumors of the pancreas. Typically, they occur in the body and tail of the pancreas in young females, often have characteristic imaging features, such as cystic components and calcification, and have a good prognosis with surgical treatment. Although SPNs are often relatively large, they have few effects on the pancreatic duct, and main pancreatic duct dilatation is rare. Their occurrence in males is also rare, and their clinical behavior in males is different from that in females. Therefore, it is more difficult to make an accurate preoperative diagnosis in males than in females. This report describes a young male patient who presented with abdominal pain due to a pancreatic mass with main pancreatic duct dilatation. There was no calcification, and the main pancreatic duct upstream of the mass was highly dilated, so pancreatic cancer was strongly suspected. However, it was possible to diagnose SPN by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA), and radical resection was successfully performed. We report a rare case of SPN in a young man with severe dilatation of the main pancreatic duct.

A 31-year-old man was admitted to the emergency department of our hospital with the chief complaint of epigastric pain.

His symptoms started several days earlier and had worsened in the last 12 h.

He had been treated for alcoholic hepatitis about five years ago at another hospital, and since then he has reduced his drinking but has not stopped drinking.

Nothing in particular.

His temperature was 36.8 °C, heart rate was 58 bpm, respiratory rate was 12 breaths per minute, blood pressure was 118/72 mmHg, and oxygen saturation on room air was 98%. There was no abnormality on examination other than mild tenderness in his upper abdomen.

Blood tests showed only a slight increase in alkaline phosphatase, and no increase in inflammatory markers or pancreatic enzymes (Table 1).

| Laboratory examination | |

| Hematologic test | |

| White blood cells | 6.3 × 103/μL |

| Red blood cells | 4.62 × 106/μL |

| Hemoglobin | 14.2 g/dL |

| Platelet count | 203 × 103/μL |

| Hematocrit | 41.7% |

| Mean corpuscular volume | 90.3 fL |

| Coagulation | |

| APTT | 26.9 s |

| PT | 103.1% |

| PT INR | 0.98 |

| Fibrinogen | 182.4 mg/dL |

| D-dimer | 0.4 mg/mL |

| Tumor marker | |

| CEA | 1.4 μg/L |

| CA19-9 | 11 U/mL |

| DUPAN-2 | < 25 U/mL |

| SPan-1 | < 10.0 U/mL |

| Chemistry | |

| Total protein | 7.1 g/dL |

| Albmin | 5.0 g/dL |

| AST | 21 U/L |

| ALT | 26 U/L |

| LDH | 162 U/L |

| ALP | 429 U/L |

| γ-GT | 28 U/L |

| Total bilirubin | 0.5 mg/dL |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 17 mg/dL |

| Creatinine | 0.80 mg/dL |

| Na | 141 mmol/L |

| K | 4.0 mmol/L |

| Cl | 104 mmol/L |

| Ca | 9.4 mmol/L |

| CRP | 0.01 mg/dL |

| Amylase | 130 U/L |

| Lipase | 53 U/L |

| Elastase1 | 215 ng/dL |

| IgG | 713 mg/dL |

| IgG4 | 38 mg/dL |

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography showed a 40-mm-diameter, hypovascular mass in the head of the pancreas. The inside was uneven, and there was a cyst-like, low-density area in some parts. The boundaries were relatively clear. The lesion was heterogeneously and slightly enhanced as the phase progressed. The main pancreatic duct upstream of the mass was severely dilated to 7 mm (Figure 1). The patient quickly improved with conservative treatment, but was evaluated further. Abdominal ultrasonography showed a well-defined, circular, hypoechoic mass in the head of the pancreas (Figure 2). Magnetic resonance imaging showed low intensity on T1- and T2-weighted images, with high intensity on T2-weighted image in some parts. The mass showed high intensity on diffusion-weighted images, and the main pancreatic duct upstream of the mass was extremely dilated on magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (Figure 3). 18F-fluorodexyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography also showed a strong increase in FDG uptake in the mass (Figure 4).

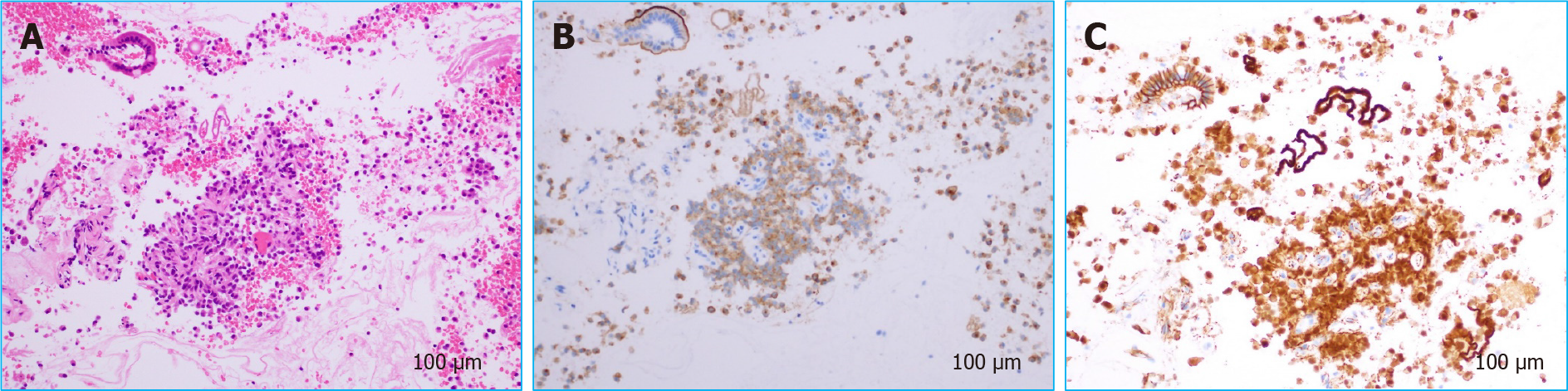

Although the patient was young, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma was the primary differential diagnosis, along with neuroendocrine tumor, adenosquamous carcinoma, anaplastic pancreatic cancer, mass-forming pancreatitis, etc. If this was pancreatic cancer, portal vein infiltration could not be ruled out, and he was a candidate for neoadjuvant chemotherapy. There were two ways to obtain a pathological diagnosis, by EUS-FNA and by pancreatic juice cytology from endoscopic retrograde pancreatography. EUS-FNA was chosen because of the risk of pancreatitis and the accuracy of diagnosis. A 22-gauge needle was used to puncture the mass from the descending duodenum (Figure 5). The pathological evaluation showed a pseudopapillary structure and a pseudorosette structure in some parts. Immunostaining showed that the tumor was β-catenin-positive and CD10-positive, suggesting a diagnosis of SPN (Figure 6).

The final diagnosis was SPN.

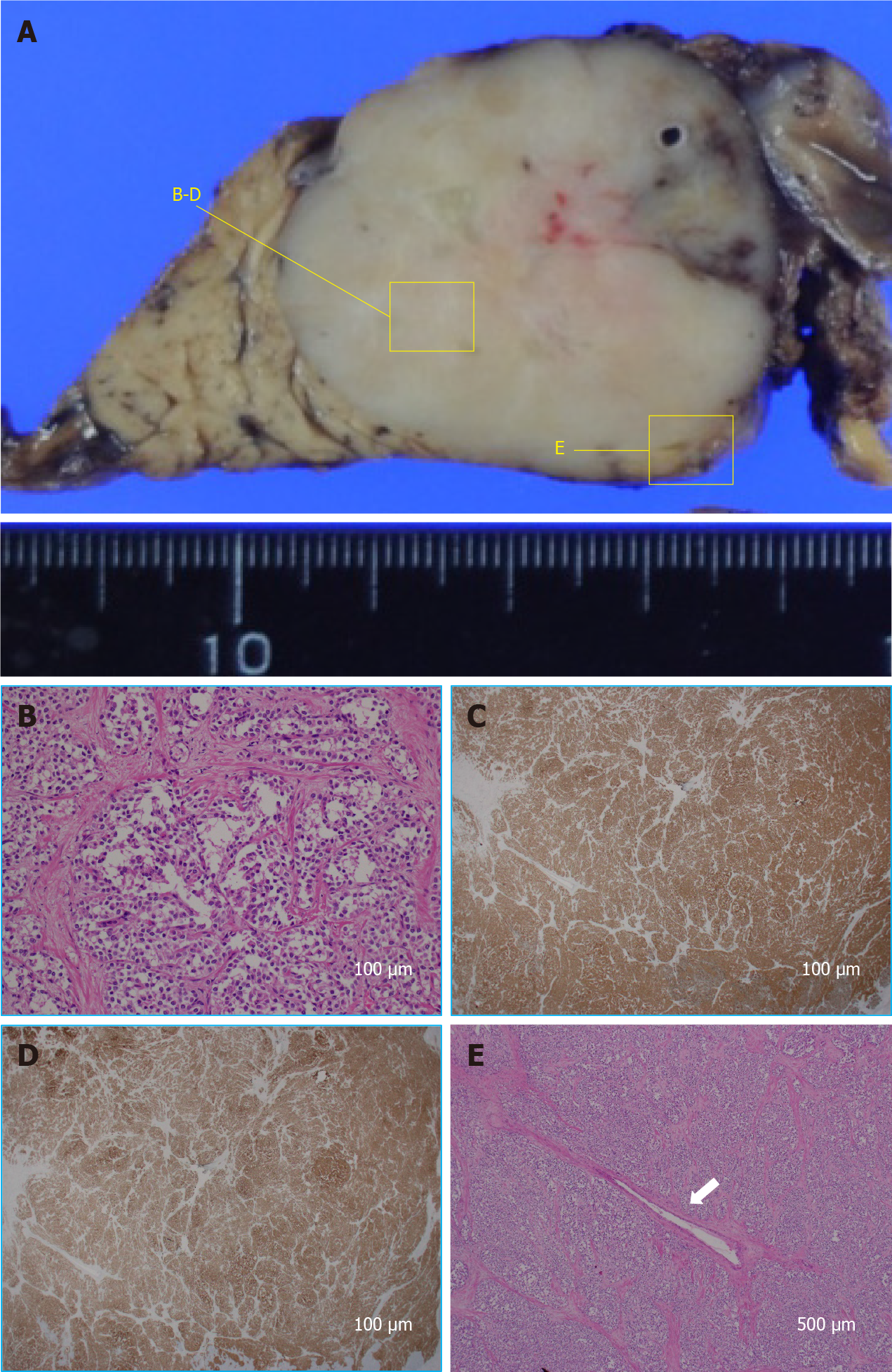

Surgical resection was considered appropriate in this case, and pancreatoduodenectomy was performed. There was no portal vein infiltration, and portal vein resection was not required. His chief complaint of epigastric pain improved after surgery.

The pathological findings of the resected specimen were also SPN (Figure 7), and radical resection was successfully performed. One year after the operation, the patient has survived with no recurrence.

SPN was first reported by Frantz in 1959 and was classified as a low-grade tumor of the pancreas in the World Health Organization’s disease classification in 1996[1,2]. Typically, it occurs in the body and tail of the pancreas in young woman, often has typical imaging features, such as cystic components and calcification, and has a good prognosis following surgical treatment. These tumors are rare, accounting for 0.3%-2.7% of all pancreatic tumors, and their histological origin and differentiation are still uncertain[3]. However, with the recent progress in imaging modalities, reports of SPN have increased, and its pathophysiology is gradually being elucidated. For example, in the past, male cases were rare, at around 3%-10%[3,4], but recent reports suggest that the rate may be as high as 23%-35%[5-8]. SPN has malignant potential, with 10%-15% already being malignant at the time of discovery, and 0.9%-6.2% demonstrating nearby organ infiltration and distant metastasis to the liver, peritoneum, and lungs[3,4,8]. Nevertheless, curability following surgical resection with negative margins for local cases is very high. On the other hand, even in cases with distant metastases, the therapeutic effect of batch resection including the metastases is also high, with reported improvement in overall survival and disease-free survival. In fact, a good prognosis has been reported, with a 5-year survival rate of over 90% for all degrees of SPN[3,4,6-8]. Therefore, accurate preoperative diagnosis is important to provide appropriate treatment at any stage.

In the present case, the patient was not female, the tumor was present in the head of the pancreas, and it was not accompanied by calcification. It was not a typical SPN, except that cystic components were suspected in some parts. Above all, pancreatic cancer was strongly suspected because of the severe dilatation of the main pancreatic duct. Main pancreatic duct dilatation is an important imaging finding as a tool for the early detection of pancreatic cancer. Pancreatic duct dilatation is sometimes observed in neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm, and chronic pancreatitis, etc., but when there is dilatation of the main pancreatic duct upstream of the pancreatic mass, the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer must be suspected. SPN is rarely associated with pancreatic duct dilatation. Lubezky et al[4] stated that none of their 32 SPN cases had pancreatic duct dilatation, and it is interesting that their cases did not show involvement of the pancreatic duct despite a relatively large mass. Moreover, Baek et al[9] reported that the absence of upstream pancreatic duct dilatation is useful for differentiating SPN from pancreatic ductal cancer, and Jang et al[10] also reported that pancreatic ductal cancer was significantly more frequently associated with pancreatic duct dilatation than was SPN. However, recent reports suggest that SPNs with dilatation of the main pancreatic duct are more common than expected. For example, De Robertis et al[11] reported that six (8.8%) of 68 SPNs present in the head and body of the pancreas in their case series had pancreatic duct dilatation. Li et al[12] also reported that three (12.5%) of the 24 SPNs present in the head and body of the pancreas in their cases had pancreatic duct dilatation. Liu et al[7] stated that pancreatic duct dilatation was observed in 25 (10.3%) of 243 consecutive SPN patients, although the details of their locations are unknown. From the previous reports, it seems that the frequency of pancreatic duct dilatation in cases with SPN of the head and body is about 10%, which is not uncommon. Although not a predominant location, it should be recognized that pancreatic duct dilatation may sometimes occur in SPNs present in the head and body of the pancreas. The above reports mention why there are cases of SPN with pancreatic duct dilatation. There is a certain proportion of SPNs with dilatation of the main pancreatic duct, but neither of them discusses the mechanism. Most pancreatic cancers have pancreatic duct dilatation because they occur in pancreatic ducts. On the other hand, even if the SPN is relatively large, it has little effect on the caudal pancreatic duct. As mentioned above, even if it occurs in the head and body of the pancreas, pancreatic duct dilatation occurs in only about 10%. Is it related to malignancy? Lee et al[13] reported that all four of the SPNs with main pancreatic duct dilatation in their series were malignant, and they presumed that pancreatic duct dilatation was caused by malignant transformation and infiltration of the pancreatic duct. On the other hand, De Robertis et al[11] stated that two of their six cases had direct tumor infiltration of the pancreatic duct, whereas the other four cases had ductal compression. Li et al[12] also reported that compression was the main cause of pancreatic duct dilatation in all three of their cases. Therefore, there is little relationship between malignancy and pancreatic duct dilatation, and compression is considered important. The present case was also not malignant, but the main pancreatic duct was severely dilated. Histological evaluation showed that the tumor surrounded the main pancreatic duct, compressing it from all directions.

We infer that compression is not the only factor involved in pancreatic duct dilatation. If it were the only cause, pancreatic duct dilatation should be correlated with size. In general, many SPNs are large and likely to compress the pancreatic duct, but pancreatic duct dilatation rarely occurs in practice. De Robertis et al[11] also reported that there was no difference in tumor size and presence of pancreatic duct dilatation in their series, and four of the six tumors with pancreatic duct dilatation had a relatively small diameter of 3 cm or less. That is, the association between size and pancreatic duct dilatation is not significant. We presume that growth speed is probably another factor. The present case had a past history of alcoholic hepatitis treated at another hospital about 5 years earlier. At that time, ultrasonography and computed tomography scan were performed, but no abnormality was found in the pancreas. Thus, it is considered that the tumor grew relatively rapidly in about 5 years. Both compression and growth speed may have led to pancreatic duct dilatation. No report has examined the relationship between SPN and pancreatic duct dilatation in the past, but the combination of compression and growth speed seems to be a sufficiently possible hypothesis based on the present patient’s clinical course. In the future, we would like to accumulate cases and increase their generalizability. This was not a typical case of SPN in that it had no characteristic features such as sex, location, or calcification, and it was accompanied by pancreatic duct dilatation. However, it is interesting because it may lead to the elucidation of the mechanism by which pancreatic duct dilatation can occur in SPNs.

In the present case, although pancreatic cancer was suspected, there was no distant metastasis even though portal vein infiltration was suspected. Therefore, the treatment policy aimed for conversion surgery after preoperative chemotherapy. However, when EUS-FNA was performed to make a histological diagnosis before chemotherapy, a pathological diagnosis of SPN was made, leading to a change in treatment policy. Several reports have shown the usefulness of EUS-FNA for SPN[14,15]. As mentioned above, it has been established that surgical resection is effective for SPN at any stage, and that EUS-FNA is important for accurate preoperative diagnosis and surgical planning. However, although SPNs often contain cystic components, EUS-FNA for cystic tumors is controversial in terms of safety. A multicenter study of FNA procedures in Europe by Karsenti et al[16] that evaluated the risk of tumor dissemination suggested that there was no recurrence or dissemination after surgery. On the other hand, Yamaguchi et al[17] reported the world’s first case of dissemination after EUS-FNA for SPN. Moreover, Virgilio et al[18] reported a case of cyst rupture caused by EUS-FNA for SPN. Lévy et al[19] and Lanke et al[20] stated that, since EUS-FNA is an invasive procedure, it is permissible to diagnose the lesion without histological evaluation and to proceed to surgical treatment in the presence of typical SPN imaging features, and that EUS-FNA should only be considered a diagnostic tool for atypical cases. Therefore, careful assessment of the indications for EUS-FNA is important. The present case had atypical characteristics, with no cystic component, which was a good indication for FNA; in fact, EUS-FNA led to the correct treatment policy and was very effective. Fortunately, there were no malignant findings, and complete resection with a negative surgical margin was obtained. A good prognosis can be expected, and the patient is still alive without recurrence.

Main pancreatic duct dilatation is usually a finding of suspected pancreatic cancer. However, pancreatic duct dilatation can occur in SPN depending on the location and growth speed. Therefore, SPN should be considered in the differential diagnosis of tumors with pancreatic duct dilatation, and pathological evaluation by EUS-FNA should be actively performed.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited manuscript; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Iwasaki E, Omiyale AO S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yan JP

| 1. | Franz V. Tumors of the pancreas, in atlas of tumor pathology, lst series, fascicle 27-28. Washington, DC, US Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 1959. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Klöppel G, Solcia E, Longnecker DS, Capella C, Sobin L. Histological typing of tumours of the exocrine pancreas. Springer Science & Business Media, 1996. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Papavramidis T, Papavramidis S. Solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas: review of 718 patients reported in English literature. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200:965-972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 512] [Cited by in RCA: 536] [Article Influence: 26.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Lubezky N, Papoulas M, Lessing Y, Gitstein G, Brazowski E, Nachmany I, Lahat G, Goykhman Y, Ben-Yehuda A, Nakache R, Klausner JM. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas: Management and long-term outcome. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43:1056-1060. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Milanetto AC, Gais Zürcher AL, Macchi L, David A, Pasquali C. Pancreatic solid pseudopapillary neoplasm in male patients: systematic review with three new cases. Updates Surg. 2021;73:1285-1295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wu J, Mao Y, Jiang Y, Song Y, Yu P, Sun S, Li S. Sex differences in solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas: A population-based study. Cancer Med. 2020;9:6030-6041. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Liu M, Liu J, Hu Q, Xu W, Liu W, Zhang Z, Sun Q, Qin Y, Yu X, Ji S, Xu X. Management of solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of pancreas: A single center experience of 243 consecutive patients. Pancreatology. 2019;19:681-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hanada K, Kurihara K, Itoi T, Katanuma A, Sasaki T, Hara K, Nakamura M, Kimura W, Suzuki Y, Sugiyama M, Ohike N, Fukushima N, Shimizu M, Ishigami K, Gabata T, Okazaki K. Clinical and Pathological Features of Solid Pseudopapillary Neoplasms of the Pancreas: A Nationwide Multicenter Study in Japan. Pancreas. 2018;47:1019-1026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Baek JH, Lee JM, Kim SH, Kim SJ, Lee JY, Han JK, Choi BI. Small (<or=3 cm) solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas at multiphasic multidetector CT. Radiology. 2010;257:97-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jang SK, Kim JH, Joo I, Jeon JH, Shin KS, Han JK, Choi BI. Differential diagnosis of pancreatic cancer from other solid tumours arising from the periampullary area on MDCT. Eur Radiol. 2015;25:2880-2888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | De Robertis R, Marchegiani G, Catania M, Ambrosetti MC, Capelli P, Salvia R, D'Onofrio M. Solid Pseudopapillary Neoplasms of the Pancreas: Clinicopathologic and Radiologic Features According to Size. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2019;213:1073-1080. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Li DL, Li HS, Xu YK, Wang QS, Chen RY, Zhou F. Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: clinical features and imaging findings. Clin Imaging. 2018;48:113-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lee JH, Yu JS, Kim H, Kim JK, Kim TH, Kim KW, Park MS, Kim JH, Kim YB, Park C. Solid pseudopapillary carcinoma of the pancreas: differentiation from benign solid pseudopapillary tumour using CT and MRI. Clin Radiol. 2008;63:1006-1014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jahangir S, Loya A, Siddiqui MT, Akhter N, Yusuf MA. Accuracy of diagnosis of solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas on fine needle aspiration: A multi-institution experience of ten cases. Cytojournal. 2015;12:29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | De Moura DTH, Coronel M, Ribeiro IB, Farias GFA, Choez MA, Rocha R, Toscano MP, De Moura EGH. The importance of endoscopic ultrasound fine-needle aspiration in the diagnosis of solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: two case reports. J Med Case Rep. 2018;12:107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Karsenti D, Caillol F, Chaput U, Perrot B, Koch S, Vuitton L, Jacques J, Valats JC, Poincloux L, Subtil C, Chabrun E, Williet N, Vanbiervliet G, Belkhodja H, Charachon A, Wangermez M, Coron E, Cholet F, Privat J, Le Baleur Y, Bichard P, Ah Soune P, Lecleire S, Palazzo M; from the GRAPHE. Safety of Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine-Needle Aspiration for Pancreatic Solid Pseudopapillary Neoplasm Before Surgical Resection: A European Multicenter Registry-Based Study on 149 Patients. Pancreas. 2020;49:34-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yamaguchi H, Morisaka H, Sano K, Nagata K, Ryozawa S, Okamoto K, Ichikawa T. Seeding of a Tumor in the Gastric Wall after Endoscopic Ultrasound-guided Fine-needle Aspiration of Solid Pseudopapillary Neoplasm of the Pancreas. Intern Med. 2020;59:779-782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Virgilio E, Mercantini P, Ferri M, Cunsolo G, Tarantino G, Cavallini M, Ziparo V. Is EUS-FNA of solid-pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas as a preoperative procedure really necessary and free of acceptable risks? Pancreatology. 2014;14:536-538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lévy P, Rebours V. The Role of Endoscopic Ultrasound in the Diagnosis of Cystic Lesions of the Pancreas. Visc Med. 2018;34:192-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lanke G, Ali FS, Lee JH. Clinical update on the management of pseudopapillary tumor of pancreas. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;10:145-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |