Published online Aug 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i8.108704

Revised: June 3, 2025

Accepted: June 19, 2025

Published online: August 19, 2025

Processing time: 100 Days and 2.3 Hours

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is commonly accompanied by neuropsychiatric sym

To explore the relationship between anxiety-depression status and psychological resilience in patients with PD and to identify associated risk factors.

A total of 188 consecutive patients with PD treated at our institution between January 2023 and December 2024 were enrolled. Anxiety was assessed using the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), depressive symptoms were measured with the Geriatric Depression scale (GDS), and psychological resilience was evaluated using the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Pearson correlation ana

The mean BAI score was 22.05 ± 10.52 (indicative of moderate anxiety), the mean GDS score was 15.81 ± 5.49 (mild depression), and the mean CD-RISC score was 51.03 ± 9.32 (moderate resilience). Correlational analysis revealed an inverse relationship between psychological resilience and both anxiety and depression scores, whereas anxiety and depression were positively correlated. Univariate analysis identified disease duration, disease severity, comorbidity burden, gross monthly household income, educational attainment, BAI scores, and GDS scores as variables significantly associated with psychological resilience. Multivariate regression analysis showed that advanced disease stage, a high comorbidity burden, lower gross monthly household income, lower educational attainment, and elevated anxiety and depression scores were independent predictors of reduced psychological resilience.

The findings highlight the prevalence of anxiety and depression among patients with PD and the presence of moderate psychological resilience. Patients with advanced disease stages, multiple comorbidities, lower socio

Core Tip: Current research on the relationship between anxiety-depression states and psychological resilience in patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) remains limited, particularly regarding a comprehensive analysis of associated risk factors. This study identified a significant inverse relationship between the severity of anxiety and depression symptoms and the levels of psychological resilience in patients with PD. Furthermore, several key factors were found to significantly inhibit psychological resilience, including a high comorbidity burden, socioeconomic disadvantages (specifically low income and limited educational attainment), and severe emotional symptoms, as assessed using the Beck Anxiety Inventory and Geriatric Depression Scale scores.

- Citation: Cai YX, Wang YJ, Liu J. Association between anxiety-depression status and psychological resilience in patients with Parkinson’s disease: A risk factor analysis. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(8): 108704

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i8/108704.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i8.108704

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder pathologically characterized by α-synuclein aggregation and basal ganglia dysfunction[1,2]. Epidemiological data indicate a rising global burden, with the number of PD cases reaching 11.77 million in 2021 and mortality in 2023 more than doubling compared to levels in 2000, disproportionately affecting older adults and males[3,4]. Disease progression is influenced by various factors, including age, gender, ethnicity, excessive dairy consumption, rapid eye movement, sleep behavior disorders, and traumatic brain injury. Clinical manifestations include motor symptoms (e.g., tremors, rigidity, bradykinesia, and postural instability) and nonmotor symptoms (e.g., dementia and uroclepsia)[5]. Notably, neuropsychiatric comorbidities-particularly anxiety and depression-commonly co-occur with PD and may precede the onset of motor symptoms. These symptoms serve as potential early biomarkers, underscoring their diagnostic value in the early detection and management of PD[6,7]. Such psychiatric disturbances severely impair cognitive function, social engagement, and overall quality of life[8].

Psychological resilience refers to an individual’s capacity to maintain or restore psychological homeostasis in the face of adversity, trauma, or significant stressors[9]. This dynamic process involves the effective utilization of intrinsic cognitive-emotional regulation strategies and extrinsic social support systems to mitigate psychological distress and facilitate recovery. The development of psychological resilience varies considerably among individuals and is shaped by life experiences, sociocultural contexts, and targeted therapeutic interventions[10]. Growing evidence suggests that psychological resilience may exert neuroprotective effects. Rosano et al[11] reported that higher levels of psychological resilience may protect against cognitive decline in neurodegenerative conditions and serve as a buffer against mood disorders, suggesting potential clinical relevance for resilience-focused interventions. Similar outcomes have been observed in adolescent populations, where psychological resilience functions both as a mediator of emotional distress and as a moderator in the association between familial support and psychological well-being[12]. In a study by Yao et al[13], positive psychology interventions based on the Positive Emotion, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accom

Despite existing insights, the relationship between psychological resilience and affective symptoms in patients with PD remains underexplored, and the associated risk factors are not well understood. This study proposes a significant association between the severity of anxiety and depression and the levels of psychological resilience in patients with PD while also identifying modifiable risk factors. The findings are expected to offer valuable insights into the following: (1) The psychological profile of patients with PD; (2) The interaction between resilience and emotional distress; and (3) Evidence-based approaches for developing targeted psychological interventions, such as resilience-building programs, to optimize nonpharmacological management strategies. Additionally, identifying risk factors associated with reduced resilience may facilitate the early detection of vulnerable patient subgroups that could benefit from timely clinical int

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Diagnosis of idiopathic PD based on established diagnostic criteria[14]; (2) Age 60 years or older; (3) Current treatment with anti-PD medications; (4) Adequate cognitive function for verbal/written communication; and (5) Availability of complete medical records. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Secondary Parkinsonism or Parkinsonism-plus syndromes; (2) Recent significant life events potentially affecting emotional status; (3) History of epilepsy; (4) Major organ dysfunction; or (5) Other severe systemic comorbidities. Using these criteria, 188 consecutive patients with PD treated at Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, between January 2023 and December 2024 were enrolled.

Trained research staff administered standardized surveys, providing consistent instructions to explain the objectives and procedures of the study. Participants completed the self-report questionnaires independently, whenever feasible. For individuals with physical limitations, the investigator orally presented the questions and recorded the responses. All questionnaires (n = 188) were distributed, verified for completeness, and collected during the same visit, resulting in a 100% valid response rate (188/188).

Demographic and clinical data: A structured questionnaire was designed to collect baseline characteristics, including gender, age, disease duration, disease severity, comorbidity burden, marital status, gross monthly household income, and educational attainment. Disease severity was assessed using the Hoehn & Yahr (H&Y) Staging System[15], with stages 1-2 classified as early PD and stages 3-5 as advanced PD. A high comorbidity burden included conditions such as hyper

Anxiety assessment: The severity of anxiety was evaluated using the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)[16], a 21-item self-report scale with item scores ranging from 0 to 3 and a total range of 0 to 63. Scores were stratified as follows: < 10, normal; 10-15, mild anxiety; 16-25, moderate anxiety; and 25, severe anxiety.

Depression assessment: Depressive symptoms were assessed using the 30-item Geriatric Depression scale (GDS)[17], a dichotomous (yes/no) questionnaire assessing emotional and behavioral symptoms, such as feelings of emptiness, worry about the future, crying, and hopelessness. The total scores were classified as follows: 0-10 (normal), 11-20 (mild depression), and 21-30 (moderate-to-severe depression).

Psychological resilience: Psychological resilience was assessed using the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC)[18], which consists of 25 items divided into three subscales: Tenacity (13 items), strength (8 items), and optimism (4 items). Responses were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (always), yielding total scores ranging from 0 to 100. Classification criteria for the levels of psychological resilience in this study were established based on Connor and Davidson’s original research and international consensus. Participants were grouped into three categories based on their psychological resilience: Low (< 50 points), moderate (50-79 points), and high (≥ 80 points). Higher scores indicate greater levels of psychological resilience. The scale exhibited good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.89.

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 24.0. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SEM, while categorical variables are expressed as counts and percentages [n (%)]. Differences between groups for categorical variables were assessed using χ2 tests. Associations among BAI, GDS, and CD-RISC scores were evaluated using Pearson correlation coefficients. Multivariate logistic regression was conducted to identify predictors of psychological resilience. Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed P value of less than 0.05.

The average BAI score among patients with PD was 22.05 ± 10.52, indicating varying levels of anxiety severity. Specifically, 28.19% of the patients exhibited mild anxiety, 32.98% moderate anxiety, and 26.60% severe anxiety, while 12.23% reported no symptoms of anxiety. Similarly, the mean GDS score was 15.81 ± 5.49, with 60.64% of patients having mild depression and 21.28% moderate-to-severe depression. Notably, 18.09% of the patients showed no depressive symptoms. Detailed results are presented in Table 1.

| Indicators | Normal | Mild | Moderate | Severe |

| BAI (points) | 22.05 ± 10.52 | |||

| 23 (12.23) | 53 (28.19) | 62 (32.98) | 50 (26.60) | |

| GDS (points) | 15.81 ± 5.49 | |||

| 34 (18.09) | 114 (60.64) | 40 (21.28) | ||

The mean total score on the CD-RISC was 51.03 ± 9.32. Subscale analysis showed mean scores of 27.44 ± 7.04 for tenacity, 16.42 ± 5.36 for strength, and 7.16 ± 2.75 for optimism. Categorizing resilience levels, 42.55% of patients had low resilience, 56.91% had moderate resilience, and only 0.53% had high resilience scores. Detailed results are presented in Table 2.

| Indicators | Low resilience | Moderate resilience | High resilience |

| CD-RISC (points) | 51.03 ± 9.32 | ||

| 80 (42.55) | 107 (56.91) | 1 (0.53) | |

| Tenacity (score) | 27.44 ± 7.04 | ||

| Strength (score) | 16.42 ± 5.36 | ||

| Optimism (score) | 7.16 ± 2.75 | ||

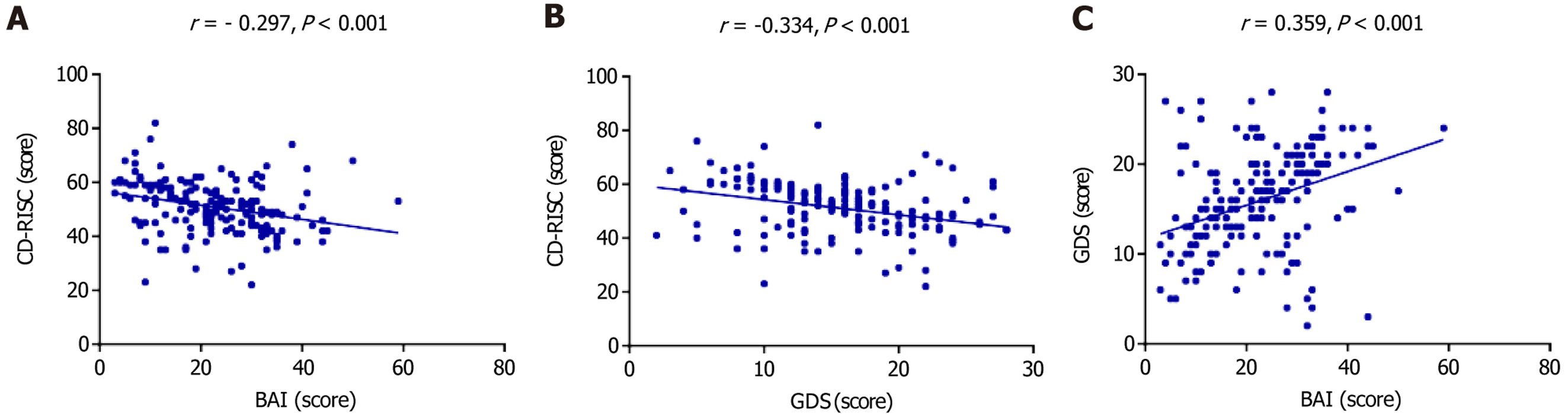

Pearson correlation analysis revealed significant associations among the psychological variables. Both BAI and GDS scores showed significant negative correlations with CD-RISC scores (P < 0.001). Additionally, a significant positive correlation was observed between BAI and GDS scores (P < 0.001). These relationships are illustrated in Figure 1.

Univariate analysis revealed no significant association between psychological resilience and gender, age, or marital status (P > 0.05). However, several clinical and socioeconomic variables were significantly associated with resilience scores, including disease duration, disease severity (as measured using the H&Y staging system), comorbidity burden, gross monthly household income, educational attainment, and both BAI and GDS scores (P < 0.05). Detailed results of the univariate analysis are presented in Table 3.

| Factors | n | Low resilience group (n = 80) | High resilience group (n = 108) | χ2 | P value |

| Gender | 0.598 | 0.439 | |||

| Male | 121 | 54 (67.50) | 67 (62.04) | ||

| Female | 67 | 26 (32.50) | 41 (37.96) | ||

| Age (years) | 1.933 | 0.164 | |||

| 60-69 | 105 | 40 (50.00) | 65 (60.19) | ||

| ≥ 70 | 83 | 40 (50.00) | 43 (39.81) | ||

| Disease duration (years) | 5.058 | 0.025 | |||

| < 5 | 86 | 29 (36.25) | 57 (52.78) | ||

| ≥ 5 | 102 | 51 (63.75) | 51 (47.22) | ||

| H&Y stage | 5.636 | 0.018 | |||

| Early stage | 108 | 38 (47.50) | 70 (64.81) | ||

| Advanced stage | 80 | 42 (52.50) | 38 (35.19) | ||

| Number of comorbidities | 7.085 | 0.029 | |||

| 0 | 65 | 22 (27.50) | 43 (39.81) | ||

| 1 | 77 | 31 (38.75) | 46 (42.59) | ||

| ≥ 2 | 46 | 27 (33.75) | 19 (17.59) | ||

| Marital status | 0.038 | 0.846 | |||

| Married | 140 | 59 (73.75) | 81 (75.00) | ||

| Unmarried/divorced/widowed | 48 | 21 (26.25) | 27 (25.00) | ||

| Gross monthly household income (yuan) | 4.339 | 0.037 | |||

| < 4000 | 113 | 55 (68.75) | 58 (53.70) | ||

| ≥ 4000 | 75 | 25 (31.25) | 50 (46.30) | ||

| Educational attainment | 7.955 | 0.005 | |||

| < Senior high school | 107 | 55 (68.75) | 52 (48.15) | ||

| ≥ Senior high school | 81 | 25 (31.25) | 56 (51.85) | ||

| BAI (points) | 6.004 | 0.014 | |||

| < 22 | 90 | 30 (37.50) | 60 (55.56) | ||

| ≥ 22 | 98 | 50 (62.50) | 48 (44.44) | ||

| GDS (points) | 4.644 | 0.031 | |||

| < 16 | 90 | 31 (38.75) | 59 (54.63) | ||

| ≥ 16 | 98 | 49 (61.25) | 49 (45.37) |

A multivariate binary logistic regression analysis was performed using CD-RISC scores as the dependent variable and the variables identified as significant in the univariate analysis (disease duration, H&Y stage, comorbidity burden, gross monthly household income, educational attainment, BAI, GDS) as independent variables. The analysis identified advanced disease severity (as indicated by a higher H&Y stage), a high comorbidity burden, and higher BAI and GDS scores as independent predictors of lower psychological resilience (P < 0.05). Conversely, higher gross monthly household income and advanced educational attainment were significant protective factors associated with increased psychological resilience (P < 0.05). The variable coding scheme and detailed regression results are presented in Tables 4 and 5, respectively.

| Factors | Variable | Assignment |

| CD-RISC (points) | Y | ≥ 50 = 0, < 50 = 1 |

| Disease duration (years) | X1 | < 5 = 0, ≥ 5 = 1 |

| H&Y stage | X2 | Early stage = 0, advanced stage = 1 |

| Number of comorbidities | X3 | 0 = 0, 1 = 1, ≥ 2 = 2 |

| Gross monthly household income | X4 | < 4000 = 0, ≥ 4000 = 1 |

| Educational attainment | X5 | < senior high school = 0, ≥ senior high school = 1 |

| BAI (points) | X6 | < 22 = 0, ≥ 22 = 1 |

| GDS (points) | X7 | < 16 = 0, ≥ 16 = 1 |

| Factors | β | SE | Wald | P value | Exp (β) | 95%CI | |

| Lower bound | Upper bound | ||||||

| Disease duration (years) | 0.597 | 0.338 | 3.123 | 0.077 | 1.817 | 0.937 | 3.523 |

| H&Y stage | 0.782 | 0.340 | 5.282 | 0.022 | 2.187 | 1.122 | 4.261 |

| Number of comorbidities | 0.518 | 0.223 | 5.411 | 0.020 | 1.679 | 1.085 | 2.598 |

| Gross monthly household income | -0.927 | 0.356 | 6.800 | 0.009 | 0.396 | 0.197 | 0.794 |

| Educational attainment | -0.972 | 0.344 | 7.995 | 0.005 | 0.378 | 0.193 | 0.742 |

| BAI (points) | 0.722 | 0.335 | 4.635 | 0.031 | 2.059 | 1.067 | 3.973 |

| GDS (points) | 0.804 | 0.338 | 5.664 | 0.017 | 2.234 | 1.152 | 4.330 |

Depression and anxiety are prevalent neuropsychiatric manifestations in patients with PD and are frequently associated with disabling behaviors and adverse clinical outcomes[19]. To improve therapeutic strategies and patient outcomes, our study evaluated key psychological dimensions-depression, anxiety, and psychological resilience-in patients with PD.

The findings indicate that patients with PD exhibited moderate anxiety levels (BAI: 22.05 ± 10.52) and mild depressive symptoms (GDS: 15.81 ± 5.49). These results are consistent with Salari et al[20], who, using the Persian version of the BAI-II, reported similar anxiety levels (18.34 ± 11.37), with moderate anxiety being the most prevalent (29.9%). This alignment persists despite potential confounding factors, including: (1) Differences in the distribution of disease stage (with our cohort including a higher proportion of advanced PD cases); (2) Variations in assessment tool versions; and (3) Cross-cultural differences in symptom reporting. Similarly, the findings of our study on depression severity align with those of Rojo et al[21], whose large-scale study (n = 353) revealed a predominance of mild depressive symptoms among patients with PD. The pathophysiological basis of these psychiatric symptoms is likely multifactorial. Clinically, anxious patients with PD often exhibit more severe motor dysfunction, diverse nonmotor symptoms, and significant impairments in daily functioning. At the molecular level, the observed psychopathology may be associated with elevated levels of hydroxyl radicals and tumor necrosis factor-α, along with reduced nitric oxide production[22].

Furthermore, L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine may contribute to mood disturbances in PD by disrupting noradrenergic and serotonergic neurotransmission, potentially exacerbating anxiety and depressive symptoms[23].

Our findings also indicate that patients with PD exhibited moderate levels of psychological resilience, as reflected by a mean CD-RISC score of 51.03 ± 9.32. This result is consistent with that of Yang et al[24], who reported similar resilience levels in a cohort of 111 patients with PD.

Correlational analyses revealed the following three key patterns: (1) A significant positive association between anxiety and depressive symptoms; (2) An inverse relationship between anxiety and psychological resilience; and (3) A negative correlation between depressive symptoms and psychological resilience. These findings align with previous research showing a significant positive correlation between depression severity and anxiety levels in patients with PD[25], as well as established resilience-depression linkages[26].

Univariate analysis identified associations between psychological resilience and several factors, including disease duration, disease severity, comorbidity burden, socioeconomic status, educational attainment, and the severity of both anxiety and depressive symptoms. Subsequent multivariate modeling using binary logistic regression delineated distinct risk and protective factors: Advanced disease stage (higher H&Y), a higher comorbidity burden, and higher BAI and GDS scores were significant risk factors, while higher gross monthly household income and advanced educational attainment exhibited protective effects. These findings indicate that patients with advanced disease stages have multiple comor

The identified risk factors for reduced psychological resilience in patients with PD appear to function through distinct yet interrelated biological and psychosocial pathways. A high comorbidity burden may precipitate a cascade of physiological stressors, including neuroendocrine dysfunction, increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines that exacerbate neuroinflammation, and adverse effects associated with polypharmacy. Together, these factors can amplify physical and psychological stress, ultimately compromising psychological resilience. Low socioeconomic disadvantages manifest through two primary mechanisms: Limited financial resources (reflected in lower gross monthly household income) limit access to supportive healthcare services, while lower educational attainment (≤ 12 years) is associated with reduced health literacy and impaired development of adaptive coping mechanisms. Clinically, the interplay between anxiety, depression, and psychological resilience is characterized by bidirectional relationships, where high BAI and GDS scores not only reflect the severity of current mood disturbances but may also predict further declines in resilience, potentially mediated by maladaptive cognitive-behavioral patterns and reduced neuroplasticity[27-30].

This study presents a novel preliminary assessment of anxiety, depression, and psychological resilience in patients with PD, delineating the distribution of severity levels across these three psychological domains. These findings are crucial for evaluating the necessity and urgency of timely psychological interventions in this patient group. Furthermore, the study identifies potential correlations between anxiety and depression and levels of psychological resilience, laying the groundwork for future research into potential causal relationships. Most importantly, this study innovatively identifies key predictors of psychological resilience, thereby developing a quantifiable metric for risk stratification and informing targeted intervention strategies in patients with PD.

Despite its contributions, the study has several limitations. First, the single-center recruitment approach may introduce selection bias, suggesting the need for future studies to adopt multicenter designs and include patients with more heterogeneous psychiatric profiles. Second, the cross-sectional nature of this study limits its ability to establish causal relationships between psychological resilience and anxiety or depression. Longitudinal studies are needed to examine these dynamic interactions over time. Last, the lack of randomized controlled trials prevents definitive conclusions regarding whether enhancing psychological resilience can alleviate emotional distress in patients with PD, highlighting a critical direction for future clinical research.

In summary, this study provides compelling evidence that psychological resilience is significantly and inversely associated with the severity of both anxiety and depression in patients with PD. Furthermore, advanced disease stage, higher comorbidity burden, lower socioeconomic status (reflected by low household income and limited educational attainment), and more severe psychiatric symptoms (based on BAI and GDS scores) are key negative predictors of psychological resilience.

| 1. | Morris HR, Spillantini MG, Sue CM, Williams-Gray CH. The pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. Lancet. 2024;403:293-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 296] [Article Influence: 296.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ye H, Robak LA, Yu M, Cykowski M, Shulman JM. Genetics and Pathogenesis of Parkinson's Syndrome. Annu Rev Pathol. 2023;18:95-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 94.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Luo Y, Qiao L, Li M, Wen X, Zhang W, Li X. Global, regional, national epidemiology and trends of Parkinson's disease from 1990 to 2021: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Front Aging Neurosci. 2024;16:1498756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ben-Shlomo Y, Darweesh S, Llibre-Guerra J, Marras C, San Luciano M, Tanner C. The epidemiology of Parkinson's disease. Lancet. 2024;403:283-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 251.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Prajjwal P, Flores Sanga HS, Acharya K, Tango T, John J, Rodriguez RSC, Dheyaa Marsool Marsool M, Sulaimanov M, Ahmed A, Hussin OA. Parkinson's disease updates: Addressing the pathophysiology, risk factors, genetics, diagnosis, along with the medical and surgical treatment. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2023;85:4887-4902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Funayama M, Nishioka K, Li Y, Hattori N. Molecular genetics of Parkinson's disease: Contributions and global trends. J Hum Genet. 2023;68:125-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 44.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kalinderi K, Papaliagkas V, Fidani L. Current genetic data on depression and anxiety in Parkinson's disease patients. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2024;118:105922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Toloraia K, Meyer A, Beltrani S, Fuhr P, Lieb R, Gschwandtner U. Anxiety, Depression, and Apathy as Predictors of Cognitive Decline in Patients With Parkinson's Disease-A Three-Year Follow-Up Study. Front Neurol. 2022;13:792830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | George T, Shah F, Tiwari A, Gutierrez E, Ji J, Kuchel GA, Cohen HJ, Sedrak MS. Resilience in older adults with cancer: A scoping literature review. J Geriatr Oncol. 2023;14:101349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ali DA, Figley CR, Tedeschi RG, Galarneau D, Amara S. Shared trauma, resilience, and growth: A roadmap toward transcultural conceptualization. Psychol Trauma. 2023;15:45-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rosano A, Bicaj M, Cillerai M, Ponzano M, Cabona C, Gemelli C, Caponnetto C, Pardini M, Signori A, Uccelli A, Schenone A, Ferraro PM. Psychological resilience is protective against cognitive deterioration in motor neuron diseases. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2024;25:717-725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ye B, Lau JTF, Lee HH, Yeung JCH, Mo PKH. The mediating role of resilience on the association between family satisfaction and lower levels of depression and anxiety among Chinese adolescents. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0283662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yao Y, Wang CJ, Yin SY, Xu GZ, Cheng YF, Huang QQ, Jin Y. Effects of positive psychology intervention based on the PERMA model on psychological status and quality of life in patients with Parkinson's disease. Heliyon. 2024;10:e36902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Höglinger G; German Parkinson’s Guidelines Committee, Trenkwalder C. Diagnosis and treatment of Parkinson´s disease (guideline of the German Society for Neurology). Neurol Res Pract. 2024;6:30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Muñoz-Mata BG, Dorantes-Méndez G, Piña-Ramírez O. Classification of Parkinson's disease severity using gait stance signals in a spatiotemporal deep learning classifier. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2024;62:3493-3506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Snodgrass MA, Bieu RK, Schroeder RW. Development of a Symptom Validity Index for the Beck Anxiety Inventory. Clin Neuropsychol. 2024;1-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cavdar VC, Ballica B, Aric M, Karaca ZB, Altunoglu EG, Akbas F. Exploring depression, comorbidities and quality of life in geriatric patients: a study utilizing the geriatric depression scale and WHOQOL-OLD questionnaire. BMC Geriatr. 2024;24:687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wojujutari AK, Idemudia ES, Ugwu LE. Evaluation of reliability generalization of Conner-Davison Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-10 and CD-RISC-25): A Meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2024;19:e0297913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Weintraub D. Management of psychiatric disorders in Parkinson's disease : Neurotherapeutics - Movement Disorders Therapeutics. Neurotherapeutics. 2020;17:1511-1524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Salari M, Zali A, Ashrafi F, Etemadifar M, Sharma S, Hajizadeh N, Ashourizadeh H. Incidence of Anxiety in Parkinson's Disease During the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. Mov Disord. 2020;35:1095-1096. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Rojo A, Aguilar M, Garolera MT, Cubo E, Navas I, Quintana S. Depression in Parkinson's disease: clinical correlates and outcome. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2003;10:23-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lian T, Zhang W, Li D, Guo P, He M, Zhang Y, Li J, Guan H, Zhang W, Luo D, Zhang W, Wang X, Zhang W. Parkinson's disease with anxiety: clinical characteristics and their correlation with oxidative stress, inflammation, and pathological proteins. BMC Geriatr. 2024;24:433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Eskow Jaunarajs KL, Angoa-Perez M, Kuhn DM, Bishop C. Potential mechanisms underlying anxiety and depression in Parkinson's disease: consequences of l-DOPA treatment. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:556-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yang M, Xue J, Kong X, Liu W, Wang Y, Zou Y, Wang L, Dong C. Correlation of psychological resilience with social support and coping style in Parkinson's disease: A cross-sectional study. J Adv Nurs. 2024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Reynolds GO, Hanna KK, Neargarder S, Cronin-Golomb A. The relation of anxiety and cognition in Parkinson's disease. Neuropsychology. 2017;31:596-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | de Figueiredo JM, Zhu B, Patel AS, Kohn R, Koo BB, Louis ED. Differential impact of resilience on demoralization and depression in Parkinson disease. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1207019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Wang Z, Wei H, Xin Y, Qin W. Advances in the study of depression and anxiety in Parkinson's disease: A review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2025;104:e41674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Shen Y, Guo X, Han C, Wan F, Ma K, Guo S, Wang L, Xia Y, Liu L, Lin Z, Huang J, Xiong N, Wang T. The implication of neuronimmunoendocrine (NIE) modulatory network in the pathophysiologic process of Parkinson's disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2017;74:3741-3768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Najafi F, Mansournia MA, Abdollahpour I, Rohani M, Vahid F, Nedjat S. Association between socioeconomic status and Parkinson's disease: findings from a large incident case-control study. BMJ Neurol Open. 2023;5:e000386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kwok JYY, Choi EPH, Chau PH, Wong JYH, Fong DYT, Auyeung M. Effects of spiritual resilience on psychological distress and health-related quality of life in Chinese people with Parkinson's disease. Qual Life Res. 2020;29:3065-3073. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |