Published online May 24, 2025. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v16.i5.106409

Revised: March 29, 2025

Accepted: April 25, 2025

Published online: May 24, 2025

Processing time: 84 Days and 0.7 Hours

Designing a feasible risk prediction model for advanced colorectal neoplasia (ACN) can enhance colonoscopy screening efficiency. Abdominal obesity is as

To propose and evaluate a modified scoring model incorporating waist-hip ratio for the prediction of ACN.

A total of 6483 patients who underwent their first screening or diagnostic co

Age, male gender, smoking, and wait-to-hip ratio were identified as independent risk factors for ACN, and a 7-point scoring model was developed. The prevalence of ACN was 3.3%, 9.3% and 18.5% in participants with scores of 0-2 [low risk (LR)], 3–4 [moderate risk (MR)], and 5–7 [high risk (HR)], respectively, in the derivation cohort. With the scoring model, 49.9%, 38.4%, and 11.7% of patients in the validation cohort were categorized as LR, MR, and HR, respectively. The corresponding prevalence rates of ACN were 5.0%, 10.3%, and 17.6%, respectively. The C-statistic of the new scoring model was 0.66, which was higher than that of the Asia-Pacific Colorectal Screening model (0.63).

A modified scoring model incorporating waist-hip ratio has an improved predictive performance in the prediction of ACN.

Core Tip: Designing a feasible risk prediction model for advanced colorectal neoplasia (ACN) can greatly improve the efficiency of colonoscopy screening. Abdominal obesity is associated with development of colorectal cancer. We proposed and evaluated a modified scoring model incorporating waist-hip ratio for the prediction of ACN in a Chinese population. Results showed that the modified scoring model had an improved predictive performance than the Asia-Pacific Colorectal Screening model in the prediction of ACN.

- Citation: Liu ZH, Cai ZL, Tong XJ, Sun YY, Zhuang XY, Yang XF, Fan JK. Modified scoring model incorporating waist-hip ratio for predicting advanced colorectal neoplasia. World J Clin Oncol 2025; 16(5): 106409

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v16/i5/106409.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v16.i5.106409

Colorectal cancer (CRC) ranks as the third most prevalent cancer diagnosis globally and represents the second primary contributor to cancer-associated fatalities[1]. It is estimated that 550000 new CRC cases and 290000 deaths occurred in China in 2020, making it the second most common cancer and the fifth leading cause of cancer-related mortality[2]. The neoplastic progression primarily originates from benign colorectal adenomatous polyps through the adenoma-carcinoma progression pathway, with advanced adenomas characterized by diameters exceeding 10 mm, presence of high-grade dysplastic changes, or villous architectural components[3]. Current preventive strategies emphasize timely identification and excision of colorectal adenomatous lesions, particularly advanced colorectal adenomas (CRAs). Clinical investigations demonstrate 53%-72% reduction in CRC incidence rates coupled with notable mortality decline following systematic endoscopic screening and polyp removal interventions[4]. While international protocols recommend initial screening colonoscopy for individuals beyond 50 years, this invasive diagnostic modality demands significant healthcare resources and carries potential procedural risks, contributing to limited global implementation-particularly within developing nations. Implementing risk stratification strategies for screening candidates could optimize resource allocation by identifying high-risk individuals requiring prioritized endoscopic evaluation.

The Asia-Pacific Consensus Recommendations[5] advocate a risk-stratified methodology utilizing the Asia-Pacific Colorectal Screening (APCS) criteria[6]. This scoring framework evaluates variables including age, gender, smoking history, and familial CRC background as predictors for advanced colorectal neoplasia (ACN). A revised APCS scoring model developed in Hong Kong integrates body mass index (BMI) as an additional parameter, demonstrating reasonable accuracy in identifying individuals at risk for ACN[7,8]. Emerging evidence highlights abdominal obesity metrics-particularly waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio-as superior predictive indicators for oncological risk compared to generalized obesity measures. The pathophysiological mechanism involves metabolically active visceral adipose tissue (VAT), which secretes numerous bioactive adipocytokines implicated in carcinogenesis[9-11].

In the present study, we developed a modified scoring model that incorporates waist-hip ratio as a parameter for predicting ACN in a Chinese population. The discriminatory performance of the new scoring system was evaluated in a validation cohort and compared with that of the APCS[6] and the BMI-modified APCS model[8].

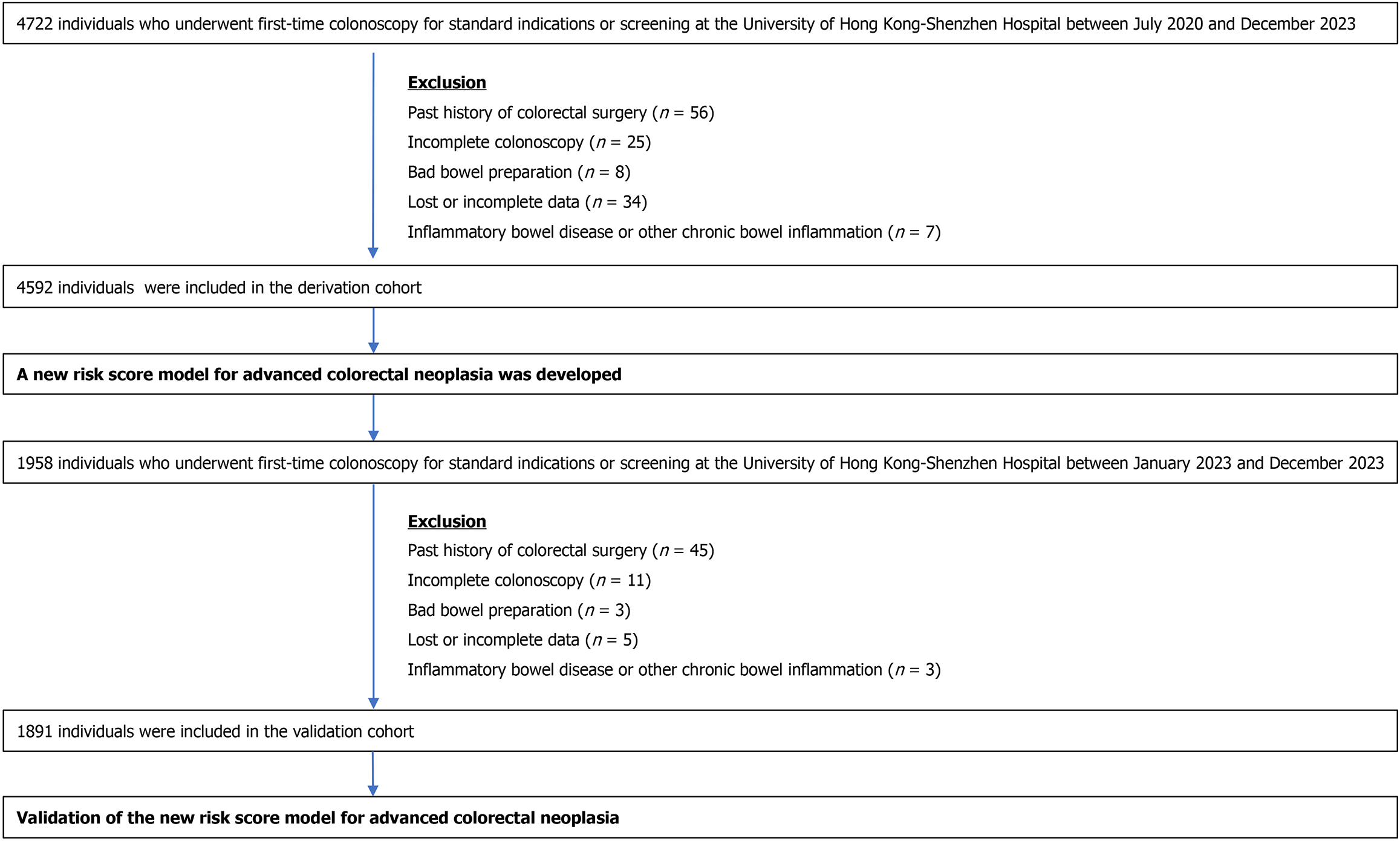

Patients aged ≥ 18 years old who underwent first-time colonoscopy for standard indications or screening at the University of Hong Kong-Shenzhen Hospital between 01/07/2020 and 31/12/2023 were recruited. Patients with a history of colectomy, poor bowel preparation, incomplete colonoscopy, inflammatory bowel disease, or other chronic bowel inflammation and those who refused to participate in the study were excluded. The study inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Figure 1.

Research assistants conducted in-person interviews to gather comprehensive patient information encompassing medical histories, coexisting health conditions, substance use patterns, hereditary cancer risks, prescribed medications, exercise routines, and symptomatic presentations. Body indices, including weight, height, waist circumference, and hip circumference, were measured and recorded.

Current smoking was classified as consuming a minimum of one cigarette daily within the past year[12,13]. Alcohol intake exceeding 140 grams weekly was categorized as regular consumption[12,13]. Physical activity involving cycling, swimming, or brisk walking for over 30 minutes daily was considered regular exercise when performed three or more times weekly[12,13]. Aspirin utilization was identified as daily intake of aspirin for a minimum of three consecutive months within the past year[12,13]. A positive family history of CRC was determined by having one or more first-degree relatives diagnosed with the condition, regardless of age[12,13].

Height assessment was conducted with a wall-mounted stadiometer, while body mass quantification employed a hospital-calibrated digital weighing instrument. Anthropometric measurements included waist circumference determination at the mid-point between the lowest rib margin and iliac crest using non-elastic measuring tape, with subjects maintaining erect posture. Concurrently, hip circumference evaluation was performed at the maximal gluteal protrusion inferior to the iliac crest, maintaining horizontal tape alignment during upright stance[12,13].

Colonoscopy procedures were conducted either directly by qualified endoscopists or under their professional guidance. In alignment with established colonoscopy quality guidelines, practitioners maintained a minimum withdrawal time exceeding six minutes during examinations. All identified colonic polyps underwent removal procedures compliant with internationally accepted surgical protocols. Excised tissue samples received initial pathological analysis from a certified specialist, followed by comprehensive reassessment conducted by a senior pathologist.

The derivation cohort enrolled patients who underwent first-time colonoscopy at our center between 01/07/2020 and 31/12/2022. Participants in the derivation cohort were divided into ACN and non-ACN groups based on their colonoscopy findings. Whereas validation cohort enrolled patients who underwent first-time colonoscopy at our center between 01/01/2023 and 31/12/2023.

In the derivation cohort, associations between ACN and clinical parameters were examined through Pearson's χ² analysis. Evaluated variables encompassed demographic characteristics (age, gender), lifestyle factors (regular exercise, smoking, alcohol consumption), medical history components [family history of CRC, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) usage, cholecystectomy], clinical symptoms (abdominal discomfort, altered bowel patterns, rectal bleeding), and anthropometric measurements [BMI, wait-to-hip ratio (WHR), and waist circumference]. For identification of independent predictors, multivariable logistic regression was employed on variables showing preliminary associations (P < 0.05) in univariate screening. All analyses utilized two-tailed tests with statistical significance threshold set at α = 0.05. The predictive scoring system incorporated regression coefficients derived from multivariable analysis, where each risk factor's weight was calculated by doubling the β-coefficient before rounding to whole numbers. Individual risk scores represented cumulative sums of weighted component values.

Within the validation cohort, subjects were stratified into three distinct risk categories according to their assessment scores: (1) Low risk (LR); (2) Moderate risk (MR); and (3) High risk (HR). The occurrence rates of ACN across these stratified groups were systematically analyzed. Model calibration was assessed through the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, with P-values exceeding 0.05 suggesting adequate calibration between predicted probabilities and actual outcomes. Comparative analysis of predictive performance was conducted using C-statistics and receiver ope

Statistical Package for Social Science (version 23.0; Chicago, IL, United States) was used for data analysis. The relationships between ACN and the clinical factors of the derivation cohort were examined by univariate analyses using the χ2 test. A BMI ≥ 23 kg/m2 was chosen as the cut-off for BMI, based on the World Health Organization (WHO) definition of being overweight for Asian populations. All variables with initial P values < 0.05 in the univariate analysis were analyzed in a binary logistic regression model to identify independent risk factors for ACN. Two-sided P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Written consents were obtained from the participants for research data collection and study purposes with identities kept confidential. The Ethics Committee of the University of Hong Kong-Shenzhen Hospital approved this study in July 2019 (No. [2019]228).

The derivation cohort enrolled 4722 patients who underwent first-time colonoscopy in our center between July 2020 and December 2022. Patients with past colorectal surgery (n = 56), incomplete colonoscopy (n = 25), poor bowel preparation

Compared with the derivation cohort, the validation cohort was older (47.1 years ± 12.4 years vs 45.8 years ± 12.4 years), and the waist circumference, WHR, and prevalence of hypertension and hyperlipemia were higher in the validation cohort, probably due to the older age of the validation cohort (P < 0.05) (Table 1). Mean value of BMI were similar in the derivation and validation cohorts (23.4 kg/m2 ± 3.3 kg/m2vs 23.3 kg/m2 ± 3.3 kg/m2). The incidences of CRA (34.3% vs 32.0%), ACN (8.5% vs 8.1%), and CRC (1.1% vs 1.3%) were not significantly different between the two cohorts (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

| Derivation cohort (n = 4592) | Validation cohort (n = 1891) | P value | |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 45.8 ± 12.4 | 47.1 ± 12.4 | 0.000 |

| Sex, male | 2458 (53.5) | 1035 (54.7) | 0.381 |

| Regular excise | 2090 (45.6) | 670 (35.4) | 0.000 |

| Smoking | 809 (17.6) | 378 (20.0) | 0.029 |

| Alcohol consumption | 606 (13.2) | 352 (18.6) | 0.000 |

| Use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | 105 (2.3) | 89 (4.7) | 0.000 |

| Hypertension | 542 (11.8) | 276 (14.6) | 0.003 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 222 (4.9) | 104 (5.5) | 0.289 |

| Hyperlipemia | 410 (8.9) | 266 (14.1) | 0.000 |

| Colorectal cancer family history | 347 (7.6) | 136 (7.2) | 0.640 |

| Post-cholecystectomy | 130 (2.9) | 34 (1.8) | 0.015 |

| Rectal bleeding | 199 (4.3) | 90 (4.8) | 0.499 |

| Change of bowel habit | 275 (6.0) | 120 (6.3) | 0.585 |

| Abdominal pain | 731 (15.9) | 354 (18.7) | 0.105 |

| Body mess index (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 23.3 ± 3.3 | 23.4 ± 3.3 | 0.264 |

| Waist circumference (cm), mean ± SD | 82.5 ± 10.3 | 83.4 ± 10.8 | 0.003 |

| Waist-hip ratio, mean ± SD | 0.885 ± 0.79 | 0.891 ± 0.89 | 0.014 |

| Normal/diverticulum/colitis/neuroendocrine neoplasms/hyperplastic polyps | 3124 (68.0) | 1241 (65.6) | 0.061 |

| Advanced colorectal neoplasia | 372 (8.1) | 161 (8.5) | 0.582 |

| Cancer | 58 (1.3) | 20 (1.1) | 0.490 |

In the univariate analysis, male gender, older age, smoking, regular intake of NSAIDs, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, BMI > 23 kg/m2, large waist circumference, and high WHR were associated with a higher ACN prevalence, while alcohol consumption, family history of CRC, excise, change of bowel habit, abdominal pain and post-cholecystectomy were not associated with the prevalence of ACN (P > 0.05) (Table 2). Multivariate regression analysis revealed that male gender, age, smoking, and increased WHR were independent risk factors for the prevalence of ACN (P < 0.05). In the multivariate regression analysis, WHR, but not BMI, was independently associated with the prevalence of ACN. Compared with females, males had an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) of ACN incidence of 1.49 (95%CI: 1.14–1.93). Compared with participants aged < 40 years, participants aged 40–49 years, 50–59 years, 60–69 years, and ≥ 70 years had AORs of ACN incidence of 3.11 (95%CI: 2.17–4.44), 3.93 (95%CI: 2.71–5.71), 5.56 (95%CI: 3.70–8.35), and 6.10 (95%CI: 3.64–10.2), respectively. Smokers had an AOR of 1.50 (95%CI: 1.14–1.98) for ACN compared with non-smokers, and participants with high WHR had an AOR of 1.46 (95%CI: 1.11–1.92) for ACN development, compared with participants with normal WHR.

| Clinical feature | Total | Advanced colorectal neoplasia | |||||

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||||

| Present (n = 372) | Absent (n = 4220) | OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | ||

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 2134 | 134 (6.3) | 2000 (93.7) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Male | 2458 | 238 (9.7) | 2220 (90.3) | 1.54 (1.26-1.89) | 0.000 | 1.49 (1.14-1.93) | 0.003 |

| Age (years) | |||||||

| < 40 | 1636 | 46 (2.8) | 1590 (97.2) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| 40–49 | 1315 | 111 (8.4) | 1204 (91.6) | 3.00 (2.15-4.20) | 3.11 (2.17-4.44) | ||

| 50–59 | 934 | 101 (10.8) | 833 (89.2) | 3.85 (2.74-5.41) | 3.93 (2.71-5.71) | ||

| 60–69 | 519 | 81 (15.6) | 438 (84.4) | 5.56 (3.92-7.87) | 5.56 (3.70-8.35) | ||

| ≥ 70 | 188 | 33 (17.6) | 155 (84.4) | 6.25 (4.10-9.52) | 0.000 | 6.10 (3.64-10.2) | 0.000 |

| Regular exercise | |||||||

| No | 2491 | 193 (7.7) | 2298 (92.3) | 1 (ref) | |||

| Yes | 2091 | 177 (8.5) | 1914 (91.5) | 1.09 (0.90-1.33) | 0.373 | ||

| Smoking | |||||||

| No | 3783 | 275 (7.3) | 3508 (92.7) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Yes | 809 | 97 (12.0) | 712 (88.0) | 1.65 (1.33-2.05) | 0.000 | 1.50 (1.14-1.98) | 0.004 |

| Alcohol drinking | |||||||

| No | 3986 | 314 (7.9) | 3673 (92.1) | 1 (ref) | |||

| Current or past drinker | 606 | 58 (9.6) | 548 (90.4) | 1.21 (0.93-1.59) | 0.158 | ||

| Regular intake of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | |||||||

| No | 4437 | 350 (7.9) | 4087 (92.1) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Yes | 105 | 18 (17.0) | 87 (83.0) | 2.16 (1.340-3.32) | 0.001 | 1.11 (0.64-1.93) | 0.707 |

| Hypertension | |||||||

| No | 4050 | 296 (7.3) | 3754 (92.7) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Yes | 542 | 76 (14.0) | 466 (86.0) | 1.92 (1.51-2.43) | 0.000 | 1.13 (0.83-1.54) | 0.423 |

| Diabetes mellitus | |||||||

| No | 4370 | 342 (7.8) | 4028 (92.2) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Yes | 222 | 30 (13.5) | 192 (86.5) | 1.72 (1.21-2.43) | 0.003 | 0.92 (0.60-1.42) | 0.718 |

| Hyperlipemia | |||||||

| No | 4182 | 324 (7.7) | 3858 (92.3) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Yes | 410 | 48 (11.7) | 362 (88.3) | 1.51 (1.13-2.01) | 0.005 | 1.03 (0.74-1.45) | 0.848 |

| Colorectal cancer family history | |||||||

| No | 4239 | 344 (8.1) | 3895 (91.9) | 1 (ref) | |||

| Yes | 347 | 28 (8.1) | 319 (91.9) | 1.01 (0.69-1.44) | 0.976 | ||

| Post cholecystectomy | |||||||

| No | 4462 | 357 (8.0) | 4105 (92.0) | 1 (ref) | |||

| Yes | 130 | 15 (11.5) | 115 (88.5) | 1.43 (0.88-2.33) | 0.154 | ||

| Rectal bleeding | |||||||

| No | 4393 | 349 (7.9) | 4044 (92.1) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Yes | 199 | 23 (11.6) | 176 (88.4) | 1.51 (0.97-2.37) | 0.068 | 1.55 (0.97-2.45) | 0.064 |

| Change of bowel habit | |||||||

| No | 4317 | 348 (8.1) | 3969 (91.9) | 1 (ref) | |||

| Yes | 275 | 24 (8.7) | 251 (91.3) | 1.09 (0.71-1.68) | 0.695 | ||

| Abdominal pain | |||||||

| No | 3861 | 320 (8.3) | 3541 (91.7) | 1 (ref) | |||

| Yes | 731 | 52 (7.1) | 679 (92.9) | 0.85 (0.63-1.15) | 0.286 | ||

| Body mass index (kg/m²) | |||||||

| ≤ 23 | 1961 | 121 (6.2) | 1840 (93.8) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| > 23 | 2621 | 249 (9.5) | 2372 (90.5) | 1.54 (1.25-1.90) | 0.000 | 1.10 (0.84-1.44) | 0.500 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | |||||||

| Normal | 2865 | 203 (7.1) | 2662 (92.9) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Higher (> 90, males; > 80, females) | 1727 | 169 (9.8) | 1558 (90.2) | 1.38 (1.14-1.68) | 0.001 | 0.90 (0.68-1.20) | 0.487 |

| Waist-hip ratio | |||||||

| Normal | 2957 | 190 (6.4) | 2767 (93.6) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Higher (> 0.9, males; > 0.85, females) | 1635 | 182 (11.1) | 1453 (88.9) | 1.73 (1.43-2.11) | 0.000 | 1.46 (1.11-1.92) | 0.006 |

An 7-point scoring model for the prediction of ACN was developed based on the beta coefficient for the four independent risk factors identified in the multivariate analysis, including male sex (score: 1), age < 40 years (score: 0), age of 40–49 years (score: 2), age of 50–59 years (score: 3), age of 60–69 years (score: 3), age > 70 years (score: 4), smoking (score: 1), and high WHR (score: 1) (Table 3). The prevalence of ACN increased from 2.5% to 26.3% in the order of calculated risk scores from 0 to 7 in the derivation cohort (Table 4). A score of 2 indicated a significantly lower prevalence of ACN than the overall prevalence (4.6% vs 8.1%), and a score of 5 indicated a significantly higher prevalence of ACN than the overall prevalence (17.4% vs 8.1%) in the derivation cohort. Therefore, scores ≤ 2 were assigned as LR, scores 5 were assigned as HR, and a score of 3 or 4 had a prevalence of ACN close to the overall prevalence (9.3% vs 8.1%) and was therefore assigned as MR. The prevalence of ACN in the derivation cohort was 3.3%, 9.3 %, and 18.5% in the LR, MR, and HR groups, respectively (Table 4).

| Clinical features | Odds ratio (95%CI) | Beta coefficient | Risk score | P value |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 1 (ref) | 0 | 0 | |

| Male | 1.49 (1.14-1.93) | 0.396 | 1 | 0.003 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| < 40 | 1 (ref) | 0 | 0 | |

| 40–49 | 3.11 (2.17-4.44) | 1.134 | 2 | |

| 50–59 | 3.93 (2.71-5.71) | 1.370 | 3 | |

| 60–69 | 5.56 (3.70-8.35) | 1.715 | 3 | |

| ≥ 70 | 6.10 (3.64-10.2) | 1.807 | 4 | 0.000 |

| Smoking | ||||

| No | 1 (ref) | 0 | 0 | |

| Yes | 1.50 (1.14-1.98) | 0.406 | 1 | 0.004 |

| Waist-hip ratio | ||||

| Normal | 1 (ref) | 0 | 0 | |

| Higher (> 0.9, males; > 0.85, females) | 1.46 (1.11-1.92) | 0.378 | 1 | 0.006 |

| Score | Proportion of individuals with ACN | 95%CI | Subgroups | Proportion of individuals with ACN | 95%CI |

| 0 | 2.5% (13/530) | 1.3–4.2 | Low-risk group (0–2) | 3.3% (63/1938) | 2.4-4.0 |

| 1 | 2.6% (19/730) | 1.6–4.0 | |||

| 2 | 4.6% (31/678) | 3.1–6.4 | |||

| 3 | 7.3% (69/944) | 5.7–9.2 | Moderate-risk group (3–4) | 9.3% (185/1983) | 8.3-10.9 |

| 4 | 11.2% (116/1039) | 9.3–13.2 | |||

| 5 | 17.4% (84/482) | 14.1–21.1 | High-risk group (5–7) | 18.5% (124/671) | 15.6-21.6 |

| 6 | 20.6% (35/170) | 14.8–27.5 | |||

| 7 | 26.3% (5/19) | 9.1–51.2 | |||

| Total | 8.1% (372/4592) | 7.3–8.9 | |||

In the validation cohort, 49.9%, 38.4 %, and 17.6% of patients were classified as LR, MR, and HR, respectively. The prevalences of ACN in the LR, MR, and HR groups of the validation cohort were 5.1%, 10.4%, and 16.2%, respectively. Compared with the LR group, the MR and HR groups had higher risks of ACN (AOR = 2.03 and AOR = 3.16, res

| Risk tier (risk score) | Derivation cohort | Validation cohort | Validation cohort (male) | Validation cohort (female) | |||||||

| Number of subjects | ACN | Number of subjects | ACN | Relative risk (95%CI) | Number of subjects | ACN | Relative risk (95%CI) | Number of subjects | Advanced colorectal neoplasia | Relative risk (95%CI) | |

| Low risk (0–2) | 1938 (42.2) | 63 (3.3) | 943 (49.9) | 47 (5.0) | 1 (ref) | 356 (34.4) | 16 (4.5) | 1 (ref) | 587 (68.6) | 31 (5.3) | 1 (ref) |

| Moderate risk (3–4) | 1983 (43.2) | 185 (9.3) | 727 (38.4) | 75 (10.3) | 2.07 (1.46-2.94) | 489 (47.2) | 42 (8.6) | 1.91 (1.09-3.34) | 238 (27.8) | 33 (13.9) | 2.62 (1.65-4.18) |

| High risk (5–7) | 671 (14.6) | 124 (18.5) | 221 (11.7) | 39 (17.6) | 3.55 (2.38-5.26) | 190 (18.4) | 32 (16.8) | 3.75 (2.11-6.67) | 31 (3.6) | 7 (22.6) | 4.27 (2.05-8.93) |

| Total | 4592 | 372 (8.1) | 1891 | 161 (8.5) | 1035 (54.7) | 90 (8.7) | 856 (45.3) | 71 (8.3) | |||

| Validation cohort (risk score model of this study) (age, male, smoking, and high wait-to-hip ratio) | Validation cohort (according to APCS model) (age, male, smoking, family history of CRC) | Validation cohort (according to modified APCS model) (age, male, smoking, family history of CRC and body mass index ) | ||||||

| Risk tier (risk score) | ACN | Relative risk (95%CI) | Risk tier (risk score) | ACN | Relative risk (95%CI) | Risk tier (risk score) | Advanced colorectal neoplasia | Relative risk (95%CI) |

| LR (0-2) | 47 (5.0) | 1 | LR (0-1) | 46 (5.1) | 1 | LR (0) | 15 (4.9) | 1 |

| MR (3-4) | 75 (10.3) | 2.07 (1.46-2.94) | MR (2-3) | 81 (10.4) | 2.03 (1.48-2.87) | MR (1–2) | 86 (7.7) | 1.58 (0.93-2.70) |

| HR (5-7) | 39 (17.6) | 3.55 (2.38-5.26) | HR (4-7) | 34 (16.2) | 3.16 (2.09-4.81) | HR (3–6) | 60 (12.9) | 2.65 (1.53-4.57) |

| Hosmer-lemeshow goodness-of-fit statistic | 0.71 | Hosmer-lemeshow goodness-of-fit statistic | 0.59 | Hosmer-lemeshow goodness-of-fit statistic | 0.27 | |||

| C-statistic | 0.66 ± 0.02 | C-statistic | 0.63 ± 0.02 | C-statistic | 0.62 ± 0.02 | |||

This single-center cross-sectional study clarified the prevalence and risk factors of ACN by examining a Chinese population and building a scoring model to predict the risk of ACN. Male sex, age, smoking, and WHR were found to be independent risk factors for ACN and were incorporated as parameters in the new scoring model for predicting ACN. A 7-point scoring model was built, in which male gender, smoking, and high WHR were all weighted as 1 point, while age had the largest weight, reaching 4 points when the patient was 70 years old. This model indicates that age plays the most important role in ACN development. Male gender and smoking are two common risk factors for most human malignancies and associated with the development of ACN and have been included as parameters in many risk models for ACN, such as the APCS and BMI-modified APCS models. Alcohol consumption is a suspected risk factor for CRC. However, it was not associated with ACN in this study, which is consistent with the results of other previous studies conducted in Asian countries, indicating that the association between alcohol consumption and the development of CRC requires further study[7,8]. The discriminative ability of the new risk model was assessed in the validation cohort and compared with that of the APCS and BMI-modified APCS models. The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit and C-statistics of the new model were 0.71 and 0.66, respectively, which were better than those of the APCS model (0.59 and 0.63, respectively) and the BMI-modified APCS model (0.27 and 0.62, respectively), indicating that the new model has a better predictive value for ACN risk.

The WHO defines overweight or obesity as excessive fat accumulation in the body, which may have negative effects on general health[13]. Obesity is associated with cancer incidence and even mortality and is a risk factor for many different types of cancer, including CRC[14,15]. BMI is the most commonly used indicator of obesity and has been shown to be a risk factor for CRC[16]. Several risk scoring models of ACN had included BMI as a scoring parameter. There are two types of obesity based on the distribution of body fat: (1) Peripheral; and (2) Central. Peripheral obesity refers to excessive adipose tissue that accumulates mainly in the trunk, whereas central obesity (also named abdominal obesity) refers to excessive adipose tissue that accumulates in the abdominal cavity, including the adipose tissue of the omentum or mesentery[17,18]. The carcinogenic effects of obesity are suspected to be associated with adipose tissue, particularly VAT. Visceral fat is an endocrine organ that produces a variety of proteins, hormones, and cytokines that are referred to as adipokines, including adiponectin, leptin, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor alpha[19]. The underlying mechanism of the positive association between central obesity and CRA may be an imbalance in the adipokines produced by visceral fat. An imbalance in adipokines contributes to carcinogenesis and promotes the development of various kinds of tumors[20]. The WHR is a simple clinical indicator of abdominal obesity. Some studies have demonstrated that WHR may be a better indicator than BMI for predicting CRC risk[9-11]. In this study, we investigated the link between BMI, WHR, metabolic syndrome (including hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia), and the incidence of ACN. Multivariate analysis revealed that WHR, but not BMI, was an independent risk factor for ACN.

Approximately 35% of patients with CRC have a family history of CRC, and the underlying mechanisms may be genetic factors, co-exposure, or a combination of both[21]. The family history of CRC is generally considered as a HR factor for the development of CRC. A study reported that individuals with two or more false discovery rates (FDRs) with CRC or individuals with one FDR diagnosed with CRC before the age of 50 years had a significantly increased risk of CRC, in whom the relative risk of developing CRC was almost three times that in the general population[22]. However, the same study suggested that only 5%–7% of patients with CRC are affected by a clearly defined inherited CRC sy

The participants in this study were younger than those in most previous studies in the world because only people aged > 50 years can participate in screening programs in most countries. However, with the plenty supply of medical resources, colonoscopy for screening purposes can be performed on demand in China, with self-financed manner. Many young people request a screening colonoscopy because of concerns about CRC, regardless of whether they have symptoms. The results showed that 2.8% of people aged < 40 years were diagnosed with ACN, and 8.4% of people aged 40–49 years had ACN, which was close to the detection rate in people aged 50–59 years (10.8%). Therefore, people aged 40-50 years should not ignore the risk of ACN. The beginning age for colonoscopy screening in the current Chinese guidelines is 40 years[24].

Most predictive risk score models for ACN are based on large-scale colonoscopy screening programs. Currently, there is no standard colonoscopy screening program in China. The subjects of this study were patients who visited the hospital for first-time colonoscopy, and some had symptoms such as rectal bleeding, abdominal pain, or changes in bowel habits. However, the statistical analysis showed that these symptoms were not directly related to the ACN detection rate, similar to the findings of a previous study in Australia[25]. This may because that these symptoms are non-specific. For example, rectal bleeding may be related to anal diseases, such as hemorrhoids, anal fissures, and enteritis, especially in young people. Changes in abdominal pain or bowel habits may be related to acute and chronic enteritis, intestinal dysfunction, or dietary changes. The proposed stratification tool shows potential for implementation in community-based screening programs and gastroenterology referrals across China. By prioritizing high-risk cohorts for endoscopic evaluation, this approach could facilitate timely detection and management of ACN, ultimately improving patient prognoses through early therapeutic interventions.

While the current risk assessment framework demonstrates notable progress in evaluating ACN susceptibility, certain limitations persist. A critical concern involves insufficient inclusion of younger demographics potentially susceptible to ACN development. Given that CRC manifestations in younger populations frequently occur without traditional risk indicators, subsequent iterations could investigate supplementary biomarkers-potentially genomic or proteomic sig

In conclusion, we developed a modified scoring model incorporating waist-hip ratio for the prediction of ACN in a Chinese population. Comparative analysis revealed the refined model demonstrated superior predictive accuracy compared to the APCS system and BMI-modified APCS system during validation testing. Future investigations involving extensive multi-institutional longitudinal studies are warranted to evaluate the clinical applicability of this novel stratification tool.

| 1. | Keum N, Giovannucci E. Global burden of colorectal cancer: emerging trends, risk factors and prevention strategies. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:713-732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 777] [Cited by in RCA: 1586] [Article Influence: 264.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Chen Y, Chen T, Fang JY. Burden of gastrointestinal cancers in China from 1990 to 2019 and projection through 2029. Cancer Lett. 2023;560:216127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Corley DA, Jensen CD, Marks AR, Zhao WK, Lee JK, Doubeni CA, Zauber AG, de Boer J, Fireman BH, Schottinger JE, Quinn VP, Ghai NR, Levin TR, Quesenberry CP. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1298-1306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1251] [Cited by in RCA: 1561] [Article Influence: 141.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Shaukat A, Kahi CJ, Burke CA, Rabeneck L, Sauer BG, Rex DK. ACG Clinical Guidelines: Colorectal Cancer Screening 2021. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:458-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 460] [Article Influence: 115.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sung JJY, Chiu HM, Lieberman D, Kuipers EJ, Rutter MD, Macrae F, Yeoh KG, Ang TL, Chong VH, John S, Li J, Wu K, Ng SSM, Makharia GK, Abdullah M, Kobayashi N, Sekiguchi M, Byeon JS, Kim HS, Parry S, Cabral-Prodigalidad PAI, Wu DC, Khomvilai S, Lui RN, Wong S, Lin YM, Dekker E. Third Asia-Pacific consensus recommendations on colorectal cancer screening and postpolypectomy surveillance. Gut. 2022;71:2152-2166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Yeoh KG, Ho KY, Chiu HM, Zhu F, Ching JY, Wu DC, Matsuda T, Byeon JS, Lee SK, Goh KL, Sollano J, Rerknimitr R, Leong R, Tsoi K, Lin JT, Sung JJ; Asia-Pacific Working Group on Colorectal Cancer. The Asia-Pacific Colorectal Screening score: a validated tool that stratifies risk for colorectal advanced neoplasia in asymptomatic Asian subjects. Gut. 2011;60:1236-1241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Sekiguchi M, Kakugawa Y, Matsumoto M, Matsuda T. A scoring model for predicting advanced colorectal neoplasia in a screened population of asymptomatic Japanese individuals. J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:1109-1119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sung JJY, Wong MCS, Lam TYT, Tsoi KKF, Chan VCW, Cheung W, Ching JYL. A modified colorectal screening score for prediction of advanced neoplasia: A prospective study of 5744 subjects. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;33:187-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jung YS, Kim NH, Yang HJ, Park SK, Park JH, Park DI, Sohn CI. Association between waist circumference and risk of colorectal neoplasia in normal-weight adults. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35:43-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Liu ZH, Zhang GX, Zhang H, Jiang L, Deng Y, Chan FSY, Fan JKM. Association of body fat distribution and metabolic syndrome with the occurrence of colorectal adenoma: A case-control study. J Dig Dis. 2021;22:222-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mili N, Paschou SA, Goulis DG, Dimopoulos MA, Lambrinoudaki I, Psaltopoulou T. Obesity, metabolic syndrome, and cancer: pathophysiological and therapeutic associations. Endocrine. 2021;74:478-497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kang HW, Kim D, Kim HJ, Kim CH, Kim YS, Park MJ, Kim JS, Cho SH, Sung MW, Jung HC, Lee HS, Song IS. Visceral obesity and insulin resistance as risk factors for colorectal adenoma: a cross-sectional, case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:178-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Nam SY, Kim BC, Han KS, Ryu KH, Park BJ, Kim HB, Nam BH. Abdominal visceral adipose tissue predicts risk of colorectal adenoma in both sexes. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:443-50.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gunter MJ, Alhomoud S, Arnold M, Brenner H, Burn J, Casey G, Chan AT, Cross AJ, Giovannucci E, Hoover R, Houlston R, Jenkins M, Laurent-Puig P, Peters U, Ransohoff D, Riboli E, Sinha R, Stadler ZK, Brennan P, Chanock SJ. Meeting report from the joint IARC-NCI international cancer seminar series: a focus on colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:510-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lauby-Secretan B, Scoccianti C, Loomis D, Grosse Y, Bianchini F, Straif K; International Agency for Research on Cancer Handbook Working Group. Body Fatness and Cancer--Viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:794-798. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2163] [Cited by in RCA: 2422] [Article Influence: 269.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bhaskaran K, Douglas I, Forbes H, dos-Santos-Silva I, Leon DA, Smeeth L. Body-mass index and risk of 22 specific cancers: a population-based cohort study of 5·24 million UK adults. Lancet. 2014;384:755-765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1017] [Cited by in RCA: 1190] [Article Influence: 108.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gao X, Zhang W, Wang Y, Pedram P, Cahill F, Zhai G, Randell E, Gulliver W, Sun G. Serum metabolic biomarkers distinguish metabolically healthy peripherally obese from unhealthy centrally obese individuals. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2016;13:33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Grassi G, Dell'Oro R, Facchini A, Quarti Trevano F, Bolla GB, Mancia G. Effect of central and peripheral body fat distribution on sympathetic and baroreflex function in obese normotensives. J Hypertens. 2004;22:2363-2369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Balistreri CR, Caruso C, Candore G. The role of adipose tissue and adipokines in obesity-related inflammatory diseases. Mediators Inflamm. 2010;2010:802078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 314] [Cited by in RCA: 336] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Coussens LM, Zitvogel L, Palucka AK. Neutralizing tumor-promoting chronic inflammation: a magic bullet? Science. 2013;339:286-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 849] [Cited by in RCA: 866] [Article Influence: 72.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kastrinos F, Samadder NJ, Burt RW. Use of Family History and Genetic Testing to Determine Risk of Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:389-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Roos VH, Mangas-Sanjuan C, Rodriguez-Girondo M, Medina-Prado L, Steyerberg EW, Bossuyt PMM, Dekker E, Jover R, van Leerdam ME. Effects of Family History on Relative and Absolute Risks for Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:2657-2667.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Dekker E, Tanis PJ, Vleugels JLA, Kasi PM, Wallace MB. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2019;394:1467-1480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1570] [Cited by in RCA: 3029] [Article Influence: 504.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 24. | Li N, Lu B, Luo C, Cai J, Lu M, Zhang Y, Chen H, Dai M. Incidence, mortality, survival, risk factor and screening of colorectal cancer: A comparison among China, Europe, and northern America. Cancer Lett. 2021;522:255-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 59.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Corte C, Zhang L, Chen J, Westbury S, Shaw J, Yeoh KG, Leong R. Validation of the Asia Pacific Colorectal Screening (APCS) score in a Western population: An alternative screening tool. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:370-375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |