Published online Oct 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i28.8595

Peer-review started: May 25, 2021

First decision: June 25, 2021

Revised: July 1, 2021

Accepted: August 10, 2021

Article in press: August 10, 2021

Published online: October 6, 2021

Processing time: 125 Days and 23.7 Hours

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is a common non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. R-CHOP is a protocol for long-term chemotherapy for DLBCL patients. Long-term chemotherapy can lead to low immunity and increase the risk of opportunistic pathogen infections in immunocompromised patients.

We report a case of coinfection with Pneumocystis jirovecii (P. jirovecii) and Legionella pneumophila (L. pneumophila) in a patient with DLBCL. The patient was a 40-year-old female who was diagnosed with DLBCL and was admitted due to pulmonary infection. P. jirovecii and L. pneumophila were detected in her bronchoalveolar lavage fluid by hexamine silver staining, isothermal amplification and metagenomic sequencing.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of P. jirovecii and L. pneumophila coinfection found in a DLBCL patient. Clinicians should be aware of the risk of complicated infection in patients undergoing long-term chemotherapy.

Core Tip: Coinfection of Pneumocystis and Legionella is very rare. This is the first case of such infection in a patient with diffuse large B cell lymphoma. This case is significate for the detection of pathogens and the diagnosis and treatment of related diseases.

- Citation: Wu WH, Hui TC, Wu QQ, Xu CA, Zhou ZW, Wang SH, Zheng W, Yin QQ, Li X, Pan HY. Pneumocystis jirovecii and Legionella pneumophila coinfection in a patient with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(28): 8595-8601

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i28/8595.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i28.8595

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is a common type of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. R-CHOP is a protocol for long-term chemotherapy for DLBCL patients[1]. The common complications of R-CHOP include febrile neutropenia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, cardiotoxicity, peripheral neuropathy and so on. Long-term chemotherapy can also reduce the immunity of patients, which increases the possibility of the development of complex infections that are difficult to treat[2]. A variety of pathogenic microorganisms, such as bacteria, fungi and viruses, may cause infection in these patients. Immunocompromised populations are susceptible to Legionella and Pneumocystis infection, but Pneumocystis and Legionella coinfection in a patient is extremely rare. To date, only two studies have reported coinfection caused by Pneumocystis and Legionella in patients. Concurrent infection with Pneumocystis and Legionella was reported in a patient with adult T cell leukaemia in Japan[3]. Pneumocystis and Legionella coinfection was also reported in an infant with infantile spasms in Israel[4]. It is a major challenge for clinicians to correctly diagnose and treat diseases caused by coinfection with these two pathogens. Here, we report for the first time a case of severe pneumonia caused by Pneumocystis jirovecii (P. jirovecii) and Legionella pneumophila (L. pneumophila) coinfection in a patient with DLBCL.

The patient was a 40-year-old female who presented with high fever six months prior to admission.

Her medical history was notable for DLBCL. After two R-CHOP treatments, the patient still had symptoms of fever.

The patient was diagnosed with DLBCL in a local hospital two months before admission.

She was treated with the R-CHOP regimen (rituximab 600 mg day 0 +, cyclophosphamide 1.1 g day 1 +, doxorubicin 40 mg day 1 +, vincristine 4 mg day 1+ and prednisone 100 mg days 1-5) for two cycles.

The body temperature was 37.8 ℃, the blood pressure was 162/104 mmHg, the pulse was regular at 147 beats per minute (bpm), and the respiratory rate was 28 breaths/min. The patient had shortness of breath, and moist rales could be heard in both lungs.

Laboratory tests showed a white blood cell count of 7.17 × 109/L, red blood cell count of 2.86 × 1012/L, haemoglobin level of 95 g/L, platelet count of 403 × 109/L, and C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 277.6 mg/L. Bone marrow cytology showed that the proliferation of nucleated cells in the bone marrow was obviously active, and the proportion of granulocyte red cells was inverted. Lymphoid malignant tumour cells accounted for 22.5% of the total cells. Bone marrow immunohistochemistry showed that the patient was CD20 (+) and TDT (-).

After anti-infective treatment, the body temperature was 36.5 °C, oxygen saturation was 91.3%, white blood cell count was 12.32 × 109/L, lymphocyte classification was 1.0%, monocyte classification was 1.0%, neutrophil classification was 97.0% and CRP level was 79.0 mg/L.

For comparison, the normal values are as follows: the white blood cell count is 4.0-10.0 × 109/L, red blood cell count is 3.5-5.0 × 1012/L, haemoglobin level is 110 g/L, platelet count is 100-300 × 109/L, CRP level is 0-10 mg/L, lymphocyte classification is 20%-30%, monocyte classification is 3%-8% and neutrophil classification is 50%-70%.

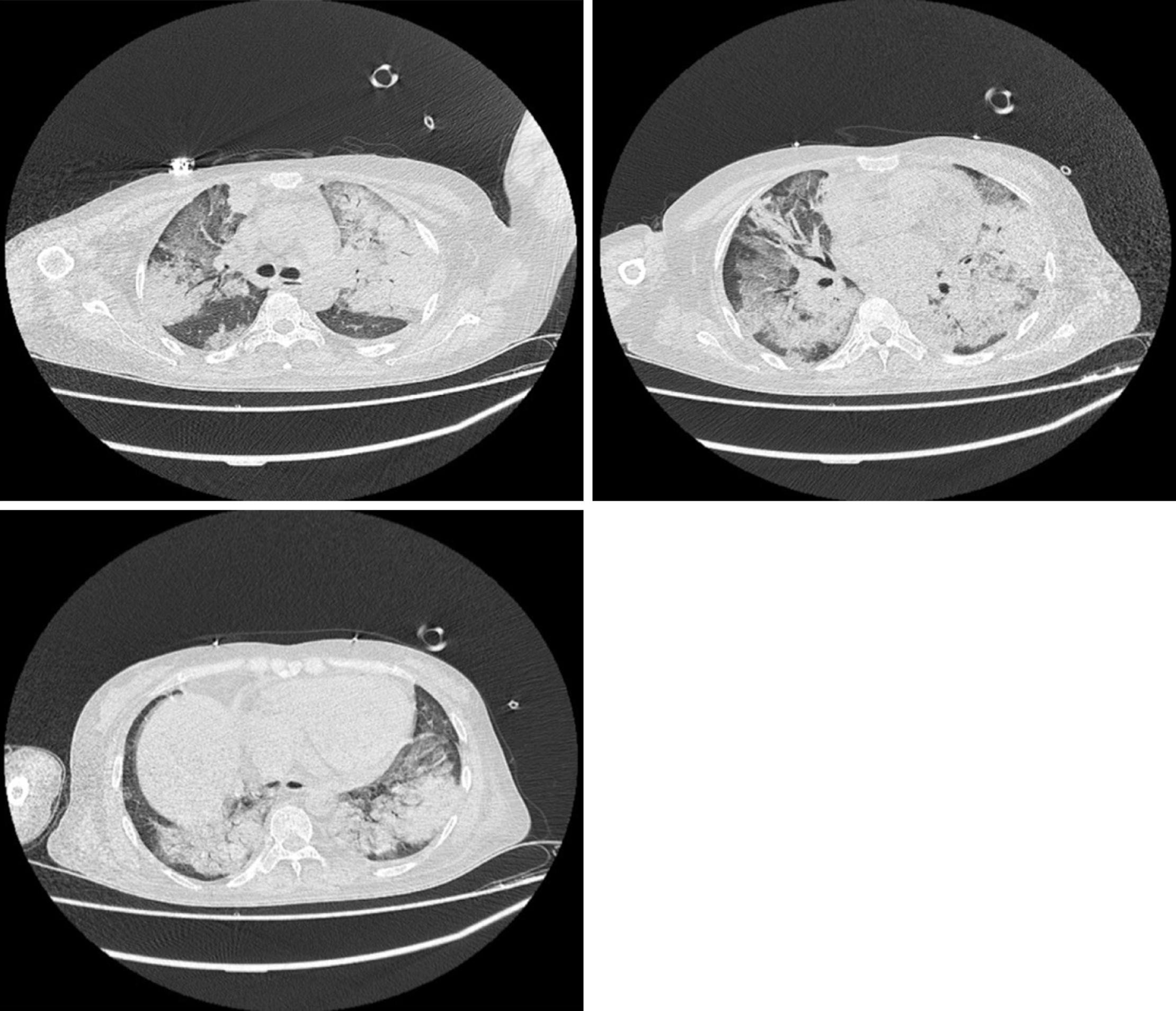

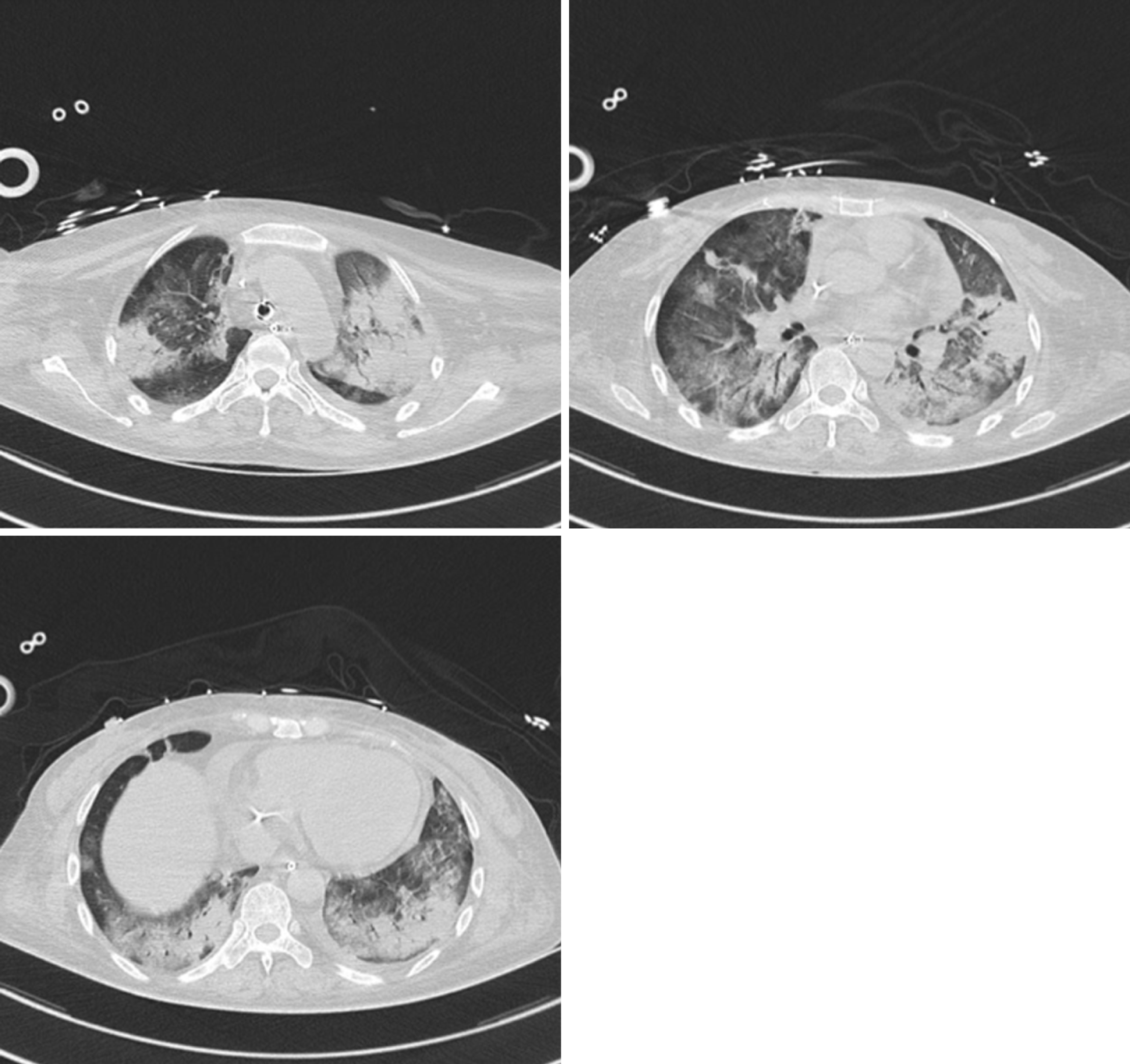

Chest computed tomography (CT) indicated multiple consolidation shadows and plaques in both lungs, and pulmonary oedema with inflammation was considered (Figure 1). After anti-infective treatment, chest CT showed that the consolidation of the lung disappeared slightly (Figure 2).

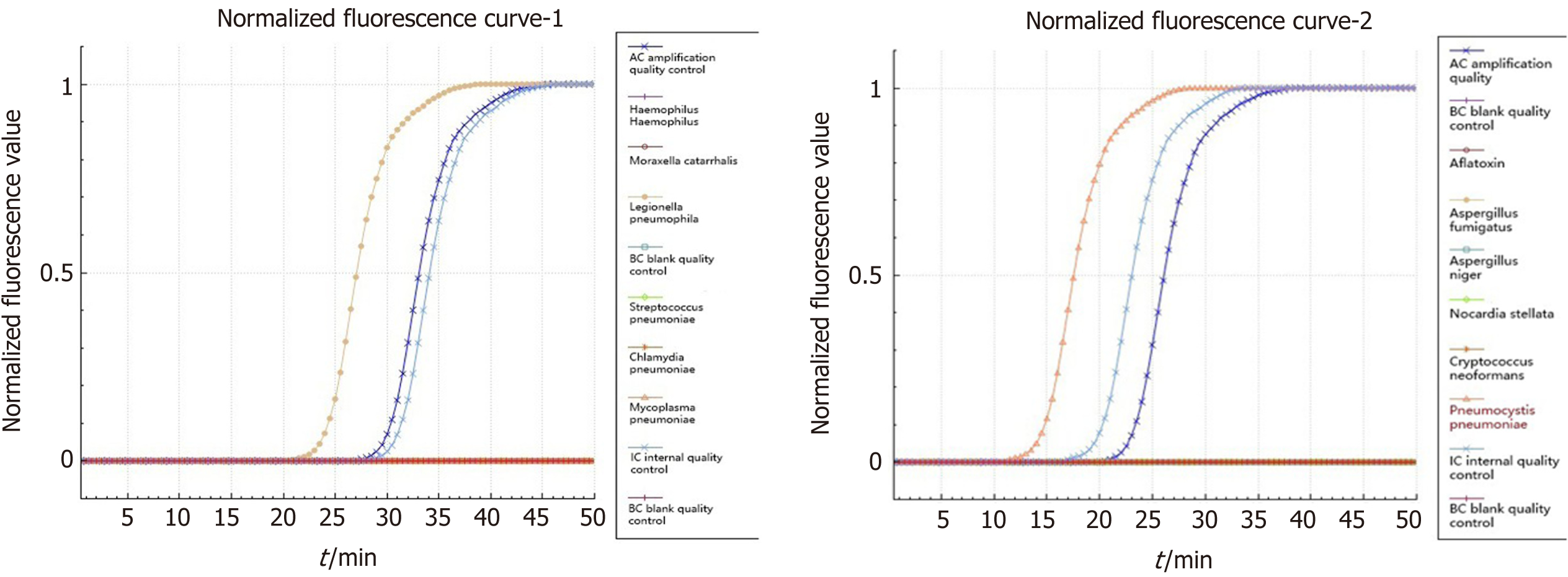

Pneumocystis was found in the patient's bronchoalveolar lavage fluid by hexamine silver staining (Figure 3). The patient's bronchoalveolar lavage fluid was sent to a third-party medical laboratory for next-generation sequencing because the present laboratory does not routinely carry out the molecular detection of pathogens. Sequence results showed that another pathogen, L. pneumophila, was also present in the patient’s bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. The previous diagnosis of P. jirovecii infection was also verified (Table 1). To verify the results of metagenome sequencing, Legionella culture and isothermal chip amplification were used to identify Legionella and Pneumocystis (Figure 4). After four days of bacterial culture, L. pneumophila grew on BCYE medium and was identified by the MALDI-TOF MS system (Figure 5).

| Types of pathogens | Number of sequences | Relative abundance |

| Legionella pneumophila | 363 | 64.82% |

| Pneumocystis jirovecii | 4758 | 99.69% |

P. jirovecii and L. pneumophila coinfection with DLBCL.

The patient was given imipenem 1 g q6h+, tigecycline 100 mg q12h+, and carprofen 5 mg qd for empirical anti-infective therapy. After the pathogens were identified as P. jirovecii and L. pneumophila, intravenous injection of 100 mL of levofloxacin was added to the treatment regimen, and compound sulfamethoxazole tablets (0.96 g q6h) were given orally. Since the patient's blood oxygen saturation fluctuated between 40% and 90%, she was given an endotracheal intubation ventilator to assist in breathing.

The patient’s condition improved after anti-infective treatment. However, the patient developed septic shock, considered to be a result of poor health status. B-ultrasound showed that her pancreas was enlarged with echo changes, which was considered drug-induced pancreatitis caused by long-term immunosuppression and the use of large-dose antibiotics. After one month of treatment in the intensive care unit, the patient finally died.

In this case, the patient suffered from diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. During long-term chemotherapy, the patient's immunity declined seriously, resulting in a complex infection. Through traditional staining and culture techniques combined with molecular diagnostic techniques, the pathogens responsible for the infection were finally identified as P. jirovecii and L. pneumophila.

Pneumocystis is a relatively primitive fungus in Ascomycota. Pneumocystidomycetes has only one order, one family and one genus. First discovered in the early 20th century, Pneumocystis lives in the lungs of humans and mammals. The first species identified was P. caterinii, thought to be a protozoan found in the lungs of mice. It was later found that P. jirovecii, which resides in human lungs, could cause Pneumocystis pneumonia in humans. Pneumocystis pneumonia is the most common disease in people with AIDS and in those with weakened immune systems[5]. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid smear microscopy is the gold standard for the diagnosis of Pneumocystis pneumonia. At present, empirical medicine has a great influence on the detection of Pneumocystis by hexamine silver staining. It is easy for Pneumocystis to be missed during detection in clinical laboratories after empirical therapy. In the present study, we found very few cases of Pneumocystis by microscopy after empirical treatment was performed. Compared with microscopy, molecular detection is a more efficient method for the diagnosis of Pneumocystis pneumonia. We further confirmed the presence of P. jirovecii in this patient by next-generation sequencing and isothermal chip amplification.

Legionella is a genus of gram-negative bacteria, and the most common and most virulent species in this genus is L. pneumophila, which was first discovered in 1976. Legionella spp. are mainly found in sewage and in the soil. Legionella spreads through the air and can lead to severe lung infections accompanied by systemic damage. Approximately 5%-15% of patients with severe pneumonia have an L. pneumophila infection[6]. Bacterial culture, urinary antigen detection and targeted PCR are common methods for Legionella detection. In China, the use of Legionella urinary antigen is limited, while targeted PCR is not available in most hospital laboratories. Bacterial culture, although effective, requires at least 72 h of culture time and may delay the treatment of critically ill patients. In this case, the presence of Pneumocystis was confirmed by hexamine silver staining. However, after anti-infection treatment, the patient still had lung symptoms. To further exclude other pathogenic bacterial infections, next-generation sequencing was performed. Notably, the results of next-generation sequencing confirmed coinfection caused by Pneumocystis and Legionella.

Sanger sequencing is considered to be a first-generation gene sequencing technology. A series of sequencing technologies developed since 2004 are known as next-generation sequencing technologies[7]. Next-generation sequencing can quickly provide a large amount of gene sequence data, which can be used to quickly sequence the whole genome, enabling broad identification of known and unexpected pathogens or even the discovery of new organisms[8]. Due to the lack of a unified standard, next-generation sequencing has not yet become a clinically recommended diagnostic technique. However, we can still use this method to aid disease prevention and diagnosis. Next-generation sequencing has played an important role in the early detection and prevention of infectious diseases. In 2011, there was an outbreak of haemorrhagic intestinal infection in Europe. Through genome sequencing, the pathogen was identified as Escherichia coli O104:H4, and its pathogenesis and transmission mechanisms were deduced through sequence analysis, which provided an important basis for clinical diagnosis and treatment[9]. In this case, we used metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) to detect pathogens. The sequencing platform was Illumina NextSeq 550, and the sequencing strategy was SE75. mNGS is a technology that does not rely on microbial culture, directly extracts nucleic acids from clinical samples for pathogen detection, and can provide results within 36 h. The Illumina NextSeq 500 sequencing platform uses the SE75 sequencing strategy and can provide 400 M high-quality reads within 11 h. A total of 13832533 DNA sequences (13.8 M reads, each 75 bp in length) were obtained, and 37984 sequences were obtained after removing the sequences derived from humans. The pathogenic microorganism database is a nonpublic database organized by the laboratory. The results showed that the number of sequences from P. jirovecii was 4758, and the relative abundance was 99.69%. The number of sequences from L. pneumophila was 363, and the relative abundance was 64.82%.

Our case is notable for several reasons. First, this is the first case report of P. jirovecii and L. pneumophila coinfection in a DLBCL patient. Second, this case reminds us to be aware of the possibility of mixed infection in immunosuppressed patients. Finally, next-generation sequencing has an important role in the diagnosis and treatment of mixed infections in immunodeficient patients. When the commonly used test methods cannot identify the causative pathogen of infections, next-generation sequencing can help clinicians save the lives of critically ill patients in a timely manner.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Infectious diseases

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Beraldo RF, Zhang X S-Editor: Liu M L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Rutherford SC, Leonard JP. DLBCL Cell of Origin: What Role Should It Play in Care Today? Oncology (Williston Park). 2018;32:445-449. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Jose Sandoval Sus, Samir Dalia, Rahul Mhaskar, Aniket Auseker, Julio Chavez, Lubomir Sokol. Intensified 14-Day Rituximab, Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, Vincristine and Prednisone (RCHOP14) Compared to R-CHOP (RCHOP21) in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials (RCT). Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018;18:S276-S277. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Arakaki N, Higa F, Tateyama M, Yamazato Y, Yara S, Ishimine T, Toyama M, Miyara T, Koide M, Saito A. Concurrent infection with Legionella pneumophila and Pneumocystis carinii in a patient with adult T cell leukemia. Intern Med. 1999;38:160-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Musallam N, Bamberger E, Srugo I, Dabbah H, Glikman D, Zonis Z, Kessel A, Genizi J. Legionella pneumophila and Pneumocystis jirovecii coinfection in an infant treated with adrenocorticotropic hormone for infantile spasm: case report and literature review. J Child Neurol. 2014;29:240-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gilroy SA, Bennett NJ. Pneumocystis pneumonia. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;32:775-782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Abu Khweek A, Amer AO. Factors Mediating Environmental Biofilm Formation by Legionella pneumophila. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Metzker ML. Sequencing technologies - the next generation. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:31-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4795] [Cited by in RCA: 4100] [Article Influence: 256.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chiu CY. Viral pathogen discovery. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2013;16:468-478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rohde H, Qin J, Cui Y, Li D, Loman NJ, Hentschke M, Chen W, Pu F, Peng Y, Li J, Xi F, Li S, Li Y, Zhang Z, Yang X, Zhao M, Wang P, Guan Y, Cen Z, Zhao X, Christner M, Kobbe R, Loos S, Oh J, Yang L, Danchin A, Gao GF, Song Y, Yang H, Wang J, Xu J, Pallen MJ, Aepfelbacher M, Yang R; E. coli O104:H4 Genome Analysis Crowd-Sourcing Consortium. Open-source genomic analysis of Shiga-toxin-producing E. coli O104:H4. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:718-724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 336] [Cited by in RCA: 311] [Article Influence: 22.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |