Published online Oct 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i28.8557

Peer-review started: May 25, 2021

First decision: June 15, 2021

Revised: June 23, 2021

Accepted: August 9, 2021

Article in press: August 9, 2021

Published online: October 6, 2021

Processing time: 126 Days and 5.2 Hours

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and patients with DLBCL typically present rapidly growing masses. Lymphoma involving muscle is rare and accounts for only 5%; furthermore, multiple muscles and soft tissue involvement of DLBCL is unusual. Due to unusual clinical manifestation, accurate diagnosis could be delayed.

A 61-year-old man complained of swelling, pain and erythematous changes in the lower abdomen. Initially, soft tissue infection was suspected, however, skin lesion did not respond to antibiotics. 18Fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography-computed tomography demonstrated FDG uptake not only in the skin and subcutaneous tissue of the abdomen but also in the abdominal wall muscles, peritoneum, perineum, penis and testis. DLBCL was confirmed by biopsy of the abdominal wall muscle and subcutaneous tissue. After intensive treatment including chemotherapy with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone, central nervous system prophylaxis (intrathecal injection of methotrexate, cytarabine and hydrocortisone) and orchiectomy, he underwent peripheral blood stem cell mobilization for an autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Despite intensive treatment, the disease progressed rapidly and the patient showed poor outcome (overall survival, 9 mo; disease free survival, 3 mo).

The first clinical manifestation of soft tissue DLBCL involving multiple muscles was similar to the infection of the soft tissue.

Core tip: The majority of diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCLs) initially present in lymph nodes as rapidly growing masses. Herein, we report an unusual case of DLBCL involving multiple muscles and soft tissue and appearing as soft tissue inflammation. Soft tissue biopsy was performed because there was no response to antibiotics, and DLBCL was confirmed. Despite aggressive chemotherapy and central nervous system (CNS) prophylaxis, the disease recurred with CNS invasion and progressed rapidly. This case highlights that skin invasions of aggressive lymphoma should be considered if there is a soft tissue infection that is unresponsive to antibiotics or progresses rapidly.

- Citation: Lee CH, Jeon SY, Yhim HY, Kwak JY. Disseminated soft tissue diffuse large B-cell lymphoma involving multiple abdominal wall muscles: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(28): 8557-8562

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i28/8557.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i28.8557

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common histologic subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and typically presents with rapidly growing lymph nodes in the neck or abdomen[1]. However, approximately 40% of DLBCL cases are initially present in extranodal sites, such as the gastrointestinal tract, central nervous system (CNS), breast, or testis. These are referred to as primary extranodal DLBCL[2,3]. Among them, lymphoma involving muscle accounts for only 5%; furthermore, multiple muscles and soft tissue involvement of DLBCL is unusual. Here, we report a case of soft tissue DLBCL disseminated to multiple abdominal wall muscles, skin, and subcutaneous tissue of the abdomen/perineum and scrotum. The first clinical manifestation was similar to that of soft tissue infection, and the disease progressed rapidly in a short period of time.

A 61-year-old man visited the emergency room complaining of lower abdominal wall swelling and pain.

The patient presented with a history of lower abdominal swelling and discomfort that started two weeks before admission and gradually worsened. He was examined at a primary medical center before visiting our hospital and was suspected of having soft tissue inflammation, such as Fournier gangrene or cellulitis.

The patient had no pertinent previous medical history.

The patient did not have any relevant family history.

The lower abdomen, penis, and scrotum were edematous and the skin showed erythematous changes. He complained of mild pain on palpation.

An initial laboratory test revealed that lactate dehydrogenase level of 1570 IU/L (normal range, 140-280 IU/L) and creatine kinase level of 1028 IU/L (normal range, 22-198 IU/L). The other blood test results were normal.

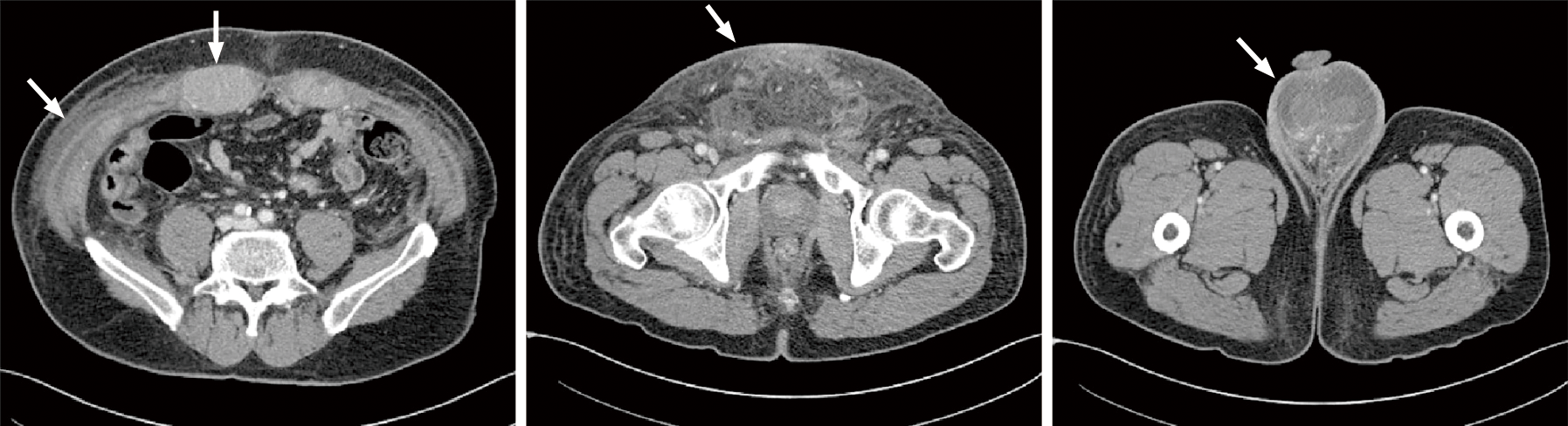

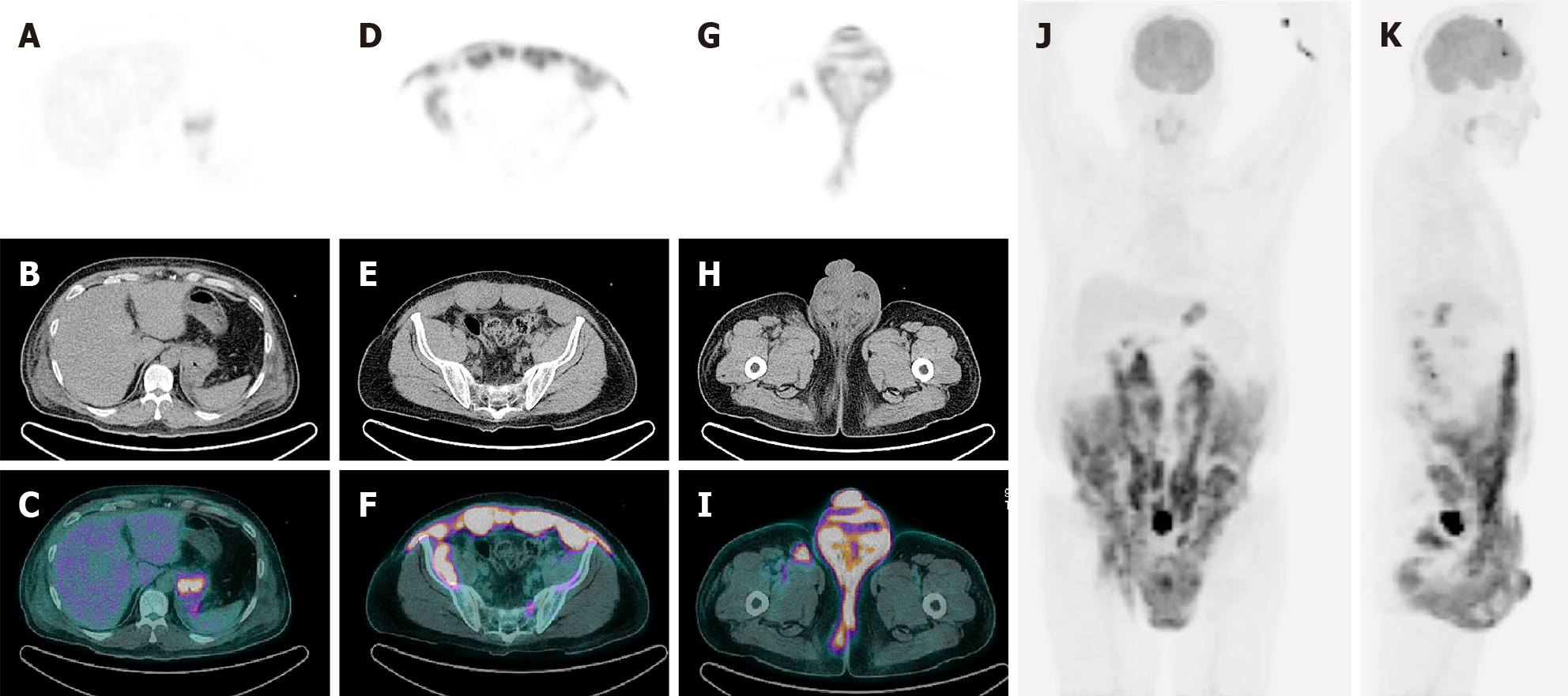

To evaluate the cause of the skin and genital lesions, a computed tomography (CT) scan was performed and soft tissue infiltration involving abdominal wall muscles, groin area, peritoneum, and retroperitoneal cavity was detected (Figure 1). Subsequently, 18Fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography-CT (18F-FDG PET-CT) was performed, and diffuse FDG uptake was detected throughout the abdominal wall muscles, skin, and subcutaneous tissue of the lower abdomen, peritoneum, perineum, anus, penis, testis, and cardia of the stomach (Figure 2).

A soft tissue infection was suspected and antibiotics were administered; however, the skin lesions did not improve. Ultrasonography-guided percutaneous biopsy of the abdominal muscles and endoscopic biopsy of the stomach were performed. DLBCL, not otherwise specified, germinal center B-cell like immunophenotype was confirmed (positive for CD20, CD10, BCL6, BCL2, and MYC). Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis was conducted to determine whether it was a double-hit or triple-hit lymphoma, and MYC rearrangement was detected.

The patient received six cycles of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone (R-CHOP) plus CNS prophylaxis (intrathecal injection of methotrexate, cytarabine, and hydrocortisone) and subsequently, underwent orchiectomy. Considering the aggressive nature of the disease, we planned an autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (auto-HSCT), and peripheral blood stem cell mobilization with dexamethasone, cytarabine, and cisplatin was performed.

Despite aggressive treatment, the disease recurred with CNS invasion one month after peripheral blood stem cell harvest. In subsequence to high-dose methotrexate therapy, three cycles of rituximab, ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide, and dexamethasone were administered as salvage therapy. Unfortunately, the patient died four weeks after salvage chemotherapy due to rapid disease progression. The overall survival and disease-free survival rates were 9 mo and 3 mo, respectively.

The patient initially presented with edema, pain, and erythematous changes in the lower abdomen and scrotum. Subsequently, soft tissue infection or inflammation was suspected and intravenous antibiotics were administered. However, the skin lesions did not show any improvement. CT revealed diffuse soft tissue infiltration in the lower abdomen and perineum; therefore, we assumed that an aggressive cancer, such as soft tissue sarcoma, arose from the abdominal wall. Subsequently, 18F-FDG PET/CT was performed, and diffuse FDG uptake in the abdominal wall muscles, including the rectus abdominis, external/internal oblique muscles, transverse abdominis, and iliacus muscles was detected. Additionally, 18F-FDG PET-CT revealed diffuse involvement of the skin and subcutaneous tissue in the lower abdomen, peritoneum, anus, penis, scrotum, testis, and stomach. Tissue samples were obtained from the abdominal wall muscle and stomach, and DLBCL was confirmed unexpectedly. Although some cases of muscle involvement of lymphoma, especially primary skeletal muscle DLBCL, have been reported to date[4-6], skeletal muscle involvement is rare and accounts for approximately 5% of extranodal lymphomas[7]. The most common sites of skeletal muscle lymphoma were the extremities and presented as painful and palpable masses. It is very rare and unusual that DLBCL initially presents as diffuse infiltration without mass formation in multiple skeletal muscles and soft tissues. This makes differentiating lymphoma from soft tissue infections challenging.

Ultrasonography is the most widely used medical imaging modality to evaluate abdominal pain or masses; however, ultrasonography features of lymphomas involving muscles are non-specific and heterogeneous. Ultrasonography shows an ill-defined hypoechoic solid mass with irregular or poorly defined margins, coarsening of fibro-adipose septa, and swelling of muscle bundles[8,9]. On the other hand, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is considered as the most useful modality to assess muscular lymphoma. Tumors show equal to slightly increased signal intensity on T1-weighted images and intermediate signal intensity compared with fat tissue on T2-weighted images. Diffuse homogeneous enhancement is usually demonstrated; however, peripheral, thick, band-like or marginal septal enhancement as well as thick irregular enhancement of both deep and superficial fascia may be found[10]. Therefore, further evaluation such as MRI is required if there is difficulty distinguishing soft tissue inflammation from lymphoma by ultrasound.

After six cycles of R-CHOP plus CNS prophylaxis, the case patient underwent orchiectomy, and peripheral blood stem cell mobilization was performed for auto-HSCT. However, despite aggressive and intensive therapy, the disease recurred with CNS invasion one month after stem cell mobilization. Although the patient received salvage therapy immediately; he died because of rapid disease progression. The overall survival and disease-free survival rates were 9 mo and 3 mo, respectively. DLBCL with testicular invasion is associated with poor outcomes and CNS relapse. After rituximab was introduced for the treatment of DLBCL, the eradication of systemic disease resulted in improvements, leading to a decrease in the risk of recurrence[11]. However, the rate of CNS relapse is still high, and treatment is challenging[12]. In the current patient, CNS relapse occurred despite receiving CNS prophylaxis. The underlying pathophysiology of DLBCL invading immune-privileged sites has been investigated to date. It has been observed that lymphoma cells invading immune-privileged sites can escape from host immunity owing to loss of human lymphocyte antigen expression on the tumor cell surface and high levels of somatic hypermutation in the immunoglobulin heavy chain genes[13]. Booman et al[14] reported that the tumor cells of primary DLBCL of immune-privileged sites share a mutation in the suppressor of p53 and apoptosis pathway. For these reasons, lymphoma involving immune-privilege sites is more aggressive than nodal disease. MYC rearrangement is an adverse prognostic factor and has been reported in 10% of DLBCL patients[15]. The 2 year overall survival of MYC rearrangement-positive patients was 35%, which was significantly lower than that of DLBCL patients without MYC rearrangement (67%)[15]. MYC rearrangement is also involved in double-hit or triple-hit lymphoma with BCL2 and BCL6 rearrangements. Since these high-grade lymphomas have a very poor prognosis, it is essential to evaluate the gene rearrangement of BCL2, BCL6, and MYC. This patient was also considered to have a double-hit or triple-hit lymphoma. However, we were not able to conduct BCL2 and BCL6, FISH, or next generation sequencing; a sufficient amount of tissue for mutation tests could not be obtained with core needle biopsy. Treatment had to be started immediately due to rapid progression; therefore, there was no time to complete additional biopsies.

In this report, we present an unusual case of DLBCL with diffuse muscle and soft tissue invasion which initially appeared to be soft tissue infection or inflammation. Due to unusual clinical manifestations, the first diagnosis was incorrect, and the disseminated extranodal invasion resulted in poor clinical outcomes. We suggest that skin invasions of aggressive lymphoma must be considered in differential diagnosis if there is a soft tissue infection that is unresponsive to antibiotics or progresses rapidly.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Mu PY, Yi XL S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Guo X

| 1. | Liu Y, Barta SK. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: 2019 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and treatment. Am J Hematol. 2019;94:604-616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 319] [Article Influence: 53.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Møller MB, Pedersen NT, Christensen BE. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: clinical implications of extranodal versus nodal presentation--a population-based study of 1575 cases. Br J Haematol. 2004;124:151-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Li S, Young KH, Medeiros LJ. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Pathology. 2018;50:74-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 459] [Cited by in RCA: 433] [Article Influence: 61.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kandel RA, Bédard YC, Pritzker KP, Luk SC. Lymphoma. Presenting as an intramuscular small cell malignant tumor. Cancer. 1984;53:1586-1589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhang L, Lin Q, Zhang L, Dong L, Li Y. Primary skeletal muscle diffuse large B cell lymphoma: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2015;10:2156-2160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Matikas A, Oikonomopoulou D, Tzannou I, Bakiri M. Primary abdominal muscle lymphoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Glass AG, Karnell LH, Menck HR. The National Cancer Data Base report on non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Cancer. 1997;80:2311-2320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Beggs I. Primary muscle lymphoma. Clin Radiol. 1997;52:203-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lim CY, Ong KO. Imaging of musculoskeletal lymphoma. Cancer Imaging. 2013;13:448-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chun CW, Jee WH, Park HJ, Kim YJ, Park JM, Lee SH, Park SH. MRI features of skeletal muscle lymphoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195:1355-1360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kwak JY. Treatment of diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Korean J Intern Med. 2012;27:369-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kridel R, Telio D, Villa D, Sehn LH, Gerrie AS, Shenkier T, Klasa R, Slack GW, Tan K, Gascoyne RD, Connors JM, Savage KJ. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with testicular involvement: outcome and risk of CNS relapse in the rituximab era. Br J Haematol. 2017;176:210-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Booman M, Douwes J, Legdeur MC, van Baarlen J, Schuuring E, Kluin P. From brain to testis: immune escape and clonal selection in a B cell lymphoma with selective outgrowth in two immune sanctuaries [correction of sanctuariesy]. Haematologica. 2007;92:69-71. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Booman M, Szuhai K, Rosenwald A, Hartmann E, Kluin-Nelemans H, de Jong D, Schuuring E, Kluin P. Genomic alterations and gene expression in primary diffuse large B-cell lymphomas of immune-privileged sites: the importance of apoptosis and immunomodulatory pathways. J Pathol. 2008;216:209-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | de Jonge AV, Roosma TJ, Houtenbos I, Vasmel WL, van de Hem K, de Boer JP, Maanen T van, Werf GL-van der, Beeker A, Timmers GJ, Schaar CG, Soesan M, Poddighe PJ, Jong D de, Chamuleau MED. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with MYC gene rearrangements: Current perspective on treatment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with MYC gene rearrangements; case series and review of the literature. Eur J Cancer. 2016;55:140-146. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |