Published online Dec 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i24.6480

Peer-review started: September 11, 2020

First decision: September 24, 2020

Revised: September 28, 2020

Accepted: October 20, 2020

Article in press: October 20, 2020

Published online: December 26, 2020

Processing time: 98 Days and 22.9 Hours

Status epilepticus in patients with hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a rare but serious condition that is refractory to antiepileptic drugs, and current treatment plans are vague. Diagnosis may be difficult without a clear history of cirrhosis. Liver transplantation (LT) is effective to alleviate symptoms, however, there are few reports about LT in the treatment of status epilepticus with HE. To our knowledge, this is the first report of status epilepticus present as initial manifestation of HE.

A 59-year-old woman with a 20-year history of heavy drinking was hospitalized for generalized tonic-clonic seizures. She reported no history of episodes of HE, stroke, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, ascites or gastrointestinal bleeding. Neurological examination revealed a comatose patient, without papilledema. Laboratory examination suggested liver cirrhosis. Plasma ammonia levels upon admission were five times normal. Brain computed tomography (CT) was normal, while abdominal CT and ultrasound revealed mild ascites, liver cirrhosis and splenomegaly. Electroencephalography (EEG)showed diffuse slow waves rhythm, consistent with HE, and sharp waves during ictal EEG corresponding to clinical semiology of focal tonic seizures. The symptoms were reversed by continuous antiepileptic treatment and lactulose. She was given oral levetiracetam, and focal aware seizures occasionally affected her 10 mo after LT.

Status epilepticus could be an initial manifestation of HE. Antiepileptic drugs combined with lactulose are essential for treatment of status epilepticus with HE, and LT is effective to prevent the relapse.

Core Tip: The incidence of status epilepticus with hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is low, but it is a life-threatening condition. To our best knowledge, this is the first report of status epilepticus present as the initial manifestation of HE. Appropriate antiepileptic drugs and lactulose are the keys to prevent neurological impairment in the early stage. The prognosis is closely related to timely identification and treatment of protopathic disease. In this case, antiepileptic drug treatment is still needed after liver transplantation, suggesting that liver transplantation does have a definite role in treating status epilepticus with HE based on decompensated alcoholic liver cirrhosis. Results at her 10 mo follow-up are encouraging.

- Citation: Cui B, Wei L, Sun LY, Qu W, Zeng ZG, Liu Y, Zhu ZJ. Status epilepticus as an initial manifestation of hepatic encephalopathy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(24): 6480-6486

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i24/6480.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i24.6480

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a brain dysfunction syndrome caused by liver insufficiency and/or portosystemic shunting. It is characterized by a wide clinical spectrum ranging from mild neuropsychological symptoms to altered consciousness or coma[1,2]. It typically presents with alteration in behavior, impairment of consciousness and alterations in motor tone[2]. According to the report of Adams and Foley[3], seizures occur in one-third of cases of end-stage of liver disease, while Rudler et al[4] reported that only 0.7% of patients present with status epilepticus in cirrhosis. Status epilepticus can be a manifestation of HE[5,6]. The incidence and pathophysiology of status epilepticus in patients with HE are still not clear, and its presence suggests a poor prognosis[6-8]. It is difficult to identify status epilepticus from HE in the absence of a history of severe liver diseases. There are no reports of status epilepticus as the initial symptom of HE. We report an intriguing case of a 59-year-old woman with status epilepticus as an initial manifestation of HE.

A 59-year-old female patient was admitted to our hospital for generalized tonic-clonic seizures for several hours with loss of consciousness.

She had a history of heavy alcohol consumption, approximately 100 g/d for more than 20 years, as well as elevated transaminases for 5 years without any examinations and treatments.

She had a 4-year history of hypertension and was treated with antihypertensive drugs. History of HE, epilepsy, stroke, brain trauma or hepatitis B/C virus infection was denied.

The patient had no significant personal and family history.

A comatose patient was observed on admission, and further clinical examination revealed no local neurological disorder or papilledema. Signs of decompensated cirrhosis showed mild jaundice, splenomegaly and lower extremity edema.

Laboratory data showed anemia, thrombopenia, increased transaminases, ammonia and total bilirubin, decreased albumin and potassium and prolonged international normalized ratio (INR) and prothrombin time (PT). On admission, the patient’s plasma ammonium (NH4+) level was 210 μmol/L (reference range: 0-45 μmol/L); platelet count, 44 × 109/L (reference range: 100-300 × 109/L); aspartate transaminase, 58 U/L (reference range: 8-40 U/L); albumin, 24 g/L (reference range: 35-55 g/L); total bilirubin, 117.8 μmol/L (reference range: 3.4-20.5 μmol/L); blood potassium, 2.8 mmol/L (reference range: 3.5-5.5 mmol/L); INR, 2.01 (reference range: 0.8-1.2); and PT, 22.6 s (reference range: 10.2-14.3 s). Hepatitis B and C antigens were negative.

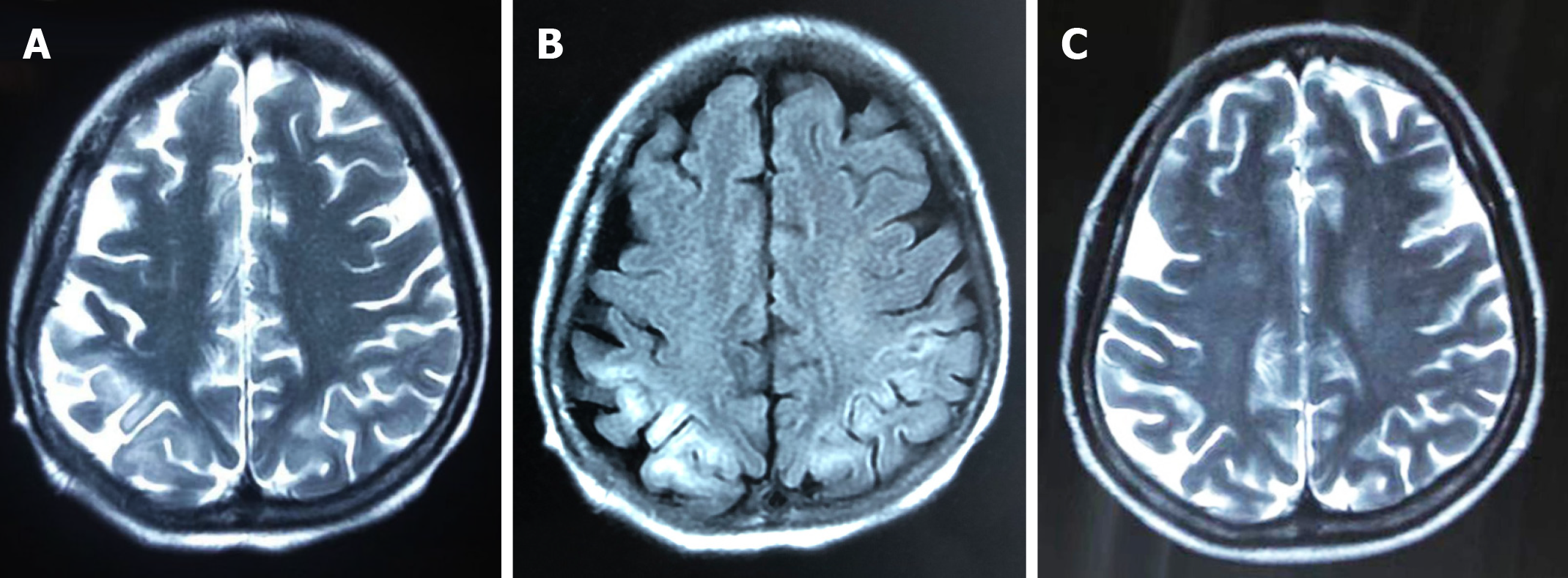

Brain computed tomography (CT) was normal. Abdominal CT and ultrasound revealed mild ascites, liver cirrhosis and splenomegaly. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed mild hyperintensities in the bilateral frontal and parietal lobes on T2-weighted sequences (Figure 1A) and hyperintensities on fluid low attenuation inversion recovery(FLAIR)-weighted sequences, similar to hypoxic/ischemic-like encephalopathy (Figure 1B). The hyperintensity area of MRI was significantly reduced after 2 mo (Figure 1C).

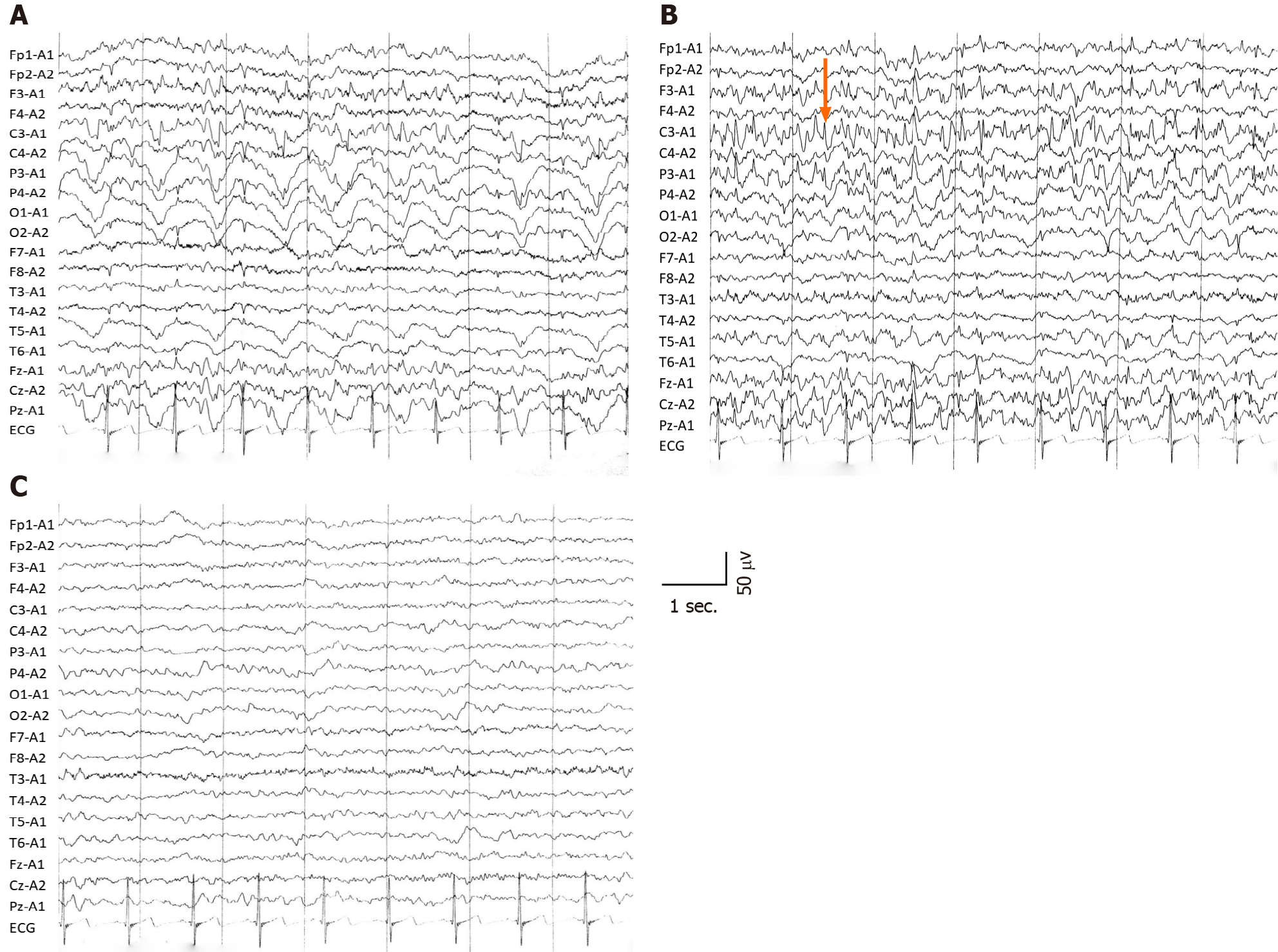

Interictal electroencephalography (EEG) showed diffuse slow waves in the parieto-occipital lobe (Figure 2A), and ictal EEG revealed sharp waves in the left parietal regions (Figure 2B). Two months after symptom onset, background EEG activity was significantly improved (Figure 2C). According to the clinical symptoms, laboratory data, radiological examination and the patient’s responses to treatment, status epilepticus with HE and decompensated alcoholic liver cirrhosis were diagnosed.

Intravenous midazolam was the initial therapy, but there was little improvement in seizures and consciousness level. Based on the laboratory results, we suspected status epilepticus related to HE. HE was resolved after 24 h therapy with lactulose, rifaximin and branched chain amino acids, and status epilepticus was resolved with continuous intravenous midazolam, which confirmed our diagnosis. Five days later, she presented with focal impaired awareness seizures, characterized by right upper extremity tonic. After 2 wk, she recovered from the episodes by increasing the dose of levetiracetam and lactulose. The level of consciousness returned to normal, seizures were terminated and blood ammonia decreased to 57 μmol/L. Levetiracetam and lactulose were continuously used. She underwent liver transplantation (LT) 3 mo after onset of disease. No complications were observed after LT. And the operation was completed in liver trasnsplantation center of Beijing Friendship Hospital, Capital Medical University.

During the first month after the operation, epileptic seizures were more frequent than before the surgery and returned to normal by adjusting the medication. It has been 10 mo since the operation, and she was followed up in the clinic. The patient was in stable condition with good consciousness level. She continued to receive levetiracetam for epilepsy and tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil for immunosuppressive treatment. Focal aware seizures lasting less than 5 sec affected her occasionally.

HE is a clinical hallmark of patients with advanced liver disease and is always a sign of deterioration[2]. Status epilepticus is a rare but life-threatening manifestation of HE[5,6,9]. It is interesting that an excitatory neurotransmission condition can manifest with a condition characterized by neuroinhibition. There are few reports concerning the mechanisms of epilepsy in HE, so the pathophysiology remains unknown. Some events of nonconvulsive status epilepticus, which resemble grade 4 HE, were misdiagnosed as HE episodes[6,8], so it is important to identify HE and status epilepticus for patients.

Alcoholic cirrhosis is more likely to cause epilepsy[4,10]. There may be several reasons for this. First, the character of alcohol is lipophilic, which easily binds to lecithin in the brain, causing degeneration, dehydration and loss or necrosis of brain cells via neurotoxicity, leading to atrophy of brain cells and diffuse brain atrophy[11]. Additionally, chronic alcohol addiction increases blood concentration of excitotoxic substances such as glutamate, aspartate and homocysteine, and alcohol withdrawal further increases the plasma level of homocysteine, lowers seizure threshold and increases the possibility of prolonged or sustained onset[12]. The “kindling” model is another underlying possible cause of seizures, which means that alcohol increases the excitability of the limbic system and subcortical structures[13]. Second, blood ammonia plays an important role in the pathogenesis by causing brain edema, energy failure and neurotransmitter alterations. Ammonia can diffuse freely across the blood–brain barrier, leading to excessive production of glutamine by glutamine synthetase in astrocytes and overactivation of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors, which can cause cell edema or even death. Moreover, hyperammonemia alters protein synthesis and exhausts the intermediate products of cell energy metabolism, leading to cell swelling, proteolysis, mitochondrial degradation and free-radical production. The effects of hyperammonemia depend on the sensitivity of the brain and are possibly reversible, so it may be a potential mechanism for treatment[14,15]. Third, with the increased permeability of the blood–brain barrier, other factors such as short-chain free fatty acids, phenols, thiols and pseudo-neurotransmitters have also been implicated[5,16]. Other under-recognized factors such as undiagnosed neurodegenerative disorders or aging may contribute to seizures in those patients, and further research on the underlying mechanisms are needed.

MRI showed mild, high signal intensity in bilateral frontoparietal lobes on T2-weighted images, while high signal intensity in FLAIR-weighted sequences was the same as in hypoxic/ischemic-like encephalopathy. Timely and effective treatment could improve prognosis and reduce the hyperintensities in MRI. Some potential reasons are related to the alterations in neuroimaging.

As mentioned above, seizures are caused by many factors that affect brain metabolism or structure and can lead to brain damage. Seizures correspond to high energy consumption and blood flow increase; therefore, when the equilibrium of blood flow and energy demand in the focal region is disrupted, lactate is released by anaerobic metabolism, resulting in destruction of the blood–brain barrier. Animal models demonstrate that, if seizures are prolonged, they can cause failure of Na+/K+-ATPase pumps, leading to cell edema or even irreversible brain damage[17]. Hypoxia or neurotransmitter imbalance caused by HE is responsible for these changes. Acute hyperammonemia selectively affects the white matter and insular and perirolandic regions, causing hypomyelination, myelination delay and cystic changes in white matter, although these changes are reversible at the beginning. Ultimately, the severity of damage depends on the duration of hyperammonemia, sensitivity of brain and age of the patient[15,18-20].

Chronic liver disease with HE is often reversible and treatable, while acute fulminant HE can lead to diffuse swelling of the brain and structural damage of the brainstem, which are difficult to treat[2]. The mortality rate reaches 50% in patients with severe HE and cirrhosis within 1 year[21,22]. A retrospective study found that the prognosis of cirrhosis patients with epileptiform discharge is poor[7]. In-hospital mortality in patients with cirrhosis and status epilepticus can reach 75%[4]. We suppose that the increase in frequency of seizures after LT is due to the rapid correction of metabolism function. The purpose of therapy is to terminate seizures quickly and reverse HE actively to prevent serious neuronal damage.

The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver guidelines recommend lactulose combined with the nonsystemic antibiotic rifaximin to prevent recurrence of HE, and the combination can reduce mortality[1]. At present, there are no standard treatments for status epilepticus with cirrhosis. Guidelines from the American Epilepsy Society suggest that intramuscular midazolam and intravenous lorazepam, diazepam and phenobarbital are established and effective initial treatments in adults with convulsive status epilepticus (Level A), while in children, intravenous lorazepam and diazepam are recommended (Level A). If the seizure lasts for more than 20 min, secondary therapy with intravenous fosphenytoin, valproic acid, levetiracetam or phenobarbital is recommended. If all the above measures fail, and seizure exceeds 40 min, repeating second-line therapy or anesthetic doses of thiopental, midazolam, pentobarbital or propofol is necessary[23]. EEG is recommended to monitor the discharge activity during treatment. Diazepam is risky in patients with liver disease because it may aggravate or induce HE[1,24], so intravenous midazolam was our first choice. Antiepileptic drugs need to be taken continuously to prevent relapse. Levetiracetam, lacosamide, topiramate, gabapentin and pregabalin are recommended first, and drugs undergoing extensive hepatic metabolism such as phenytoin, valproate and carbamazepine are the last resort[24]. Plans for drug withdrawal should be developed and executed in consultation with neurologists according to EEG and clinical symptoms[25].

Slow wave rhythm was a marked EEG change in patients with HE[7], and sharp waves were located in the left parietal region in the ictal stage, consistent with the clinical symptoms of the present patient. The background activities of EEG were improved with continuous treatment, and combined with laboratory data, the diagnosis of status epilepticus as the initial manifestation of HE based on decompensated alcoholic cirrhosis was supported.

Although not all manifestations are reversible by LT[1], it remains the final option for HE. Some reports suggest that damage to the central nervous system is reversible when elevated blood ammonia concentration does not exceed 200-400 mg/dL[26], and continuous improvement in cognition has been observed during the first year post-LT[10]. It has been also reported that 10% of patients present with seizures post-LT[9]. Seizure is not an indication for LT, and more attention should be paid to seizures prior to LT to prevent fatal status epilepticus post-LT. However, there are lack of efficient neurological evaluations that can be undertaken to assess the degree of damage and the possibility of recovery for those patients. Effective measures are urgently needed to evaluate neurological dysfunction and to identify patients with a potential benefit from LT. The data of this study support the idea that LT is effective to treat status epilepticus in patients with HE.

In view of the high mortality of status epilepticus with HE, early diagnosis and treatment play a crucial role in prognosis. To prevent progressive deterioration of liver function, it is important to select the proper antiepileptic drugs. Although not all neurological symptoms can be improved, LT remains the final option for status epilepticus with HE in alcoholic liver cirrhosis.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: El Amrousy D S-Editor: Chen XF L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Vilstrup H, Amodio P, Bajaj J, Cordoba J, Ferenci P, Mullen KD, Weissenborn K, Wong P. Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 Practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver. Hepatology. 2014;60:715-735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1583] [Cited by in RCA: 1405] [Article Influence: 127.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Wijdicks EFM. Hepatic Encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | ADAMS RD, FOLEY JM. The neurological disorder associated with liver disease. Res Publ Assoc Res Nerv Ment Dis. 1953;32:198-237. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Rudler M, Marois C, Weiss N, Thabut D, Navarro V; Brain-Liver Pitié-Salpêtrière Study Group (BLIPS). Status epilepticus in patients with cirrhosis: How to avoid misdiagnosis in patients with hepatic encephalopathy. Seizure. 2017;45:192-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Tanaka H, Ueda H, Kida Y, Hamagami H, Tsuji T, Ichinose M. Hepatic encephalopathy with status epileptics: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:1793-1794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Eleftheriadis N, Fourla E, Eleftheriadis D, Karlovasitou A. Status epilepticus as a manifestation of hepatic encephalopathy. Acta Neurol Scand. 2003;107:142-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ficker DM, Westmoreland BF, Sharbrough FW. Epileptiform abnormalities in hepatic encephalopathy. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1997;14:230-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Delanty N, French JA, Labar DR, Pedley TA, Rowan AJ. Status epilepticus arising de novo in hospitalized patients: an analysis of 41 patients. Seizure. 2001;10:116-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Weiss N, Thabut D. Neurological Complications Occurring After Liver Transplantation: Role of Risk Factors, Hepatic Encephalopathy, and Acute (on Chronic) Brain Injury. Liver Transpl. 2019;25:469-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Allampati SK, Mullen KD. Understanding the impact of neurologic complications in patients with cirrhosis. SAGE Open Med. 2019;7:2050312119832090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Meyer-Wahl JG, Braun J. Epileptic seizures and cerebral atrophy in alcoholics. J Neurol. 1982;228:17-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Leach JP, Mohanraj R, Borland W. Alcohol and drugs in epilepsy: pathophysiology, presentation, possibilities, and prevention. Epilepsia. 2012;53 Suppl 4:48-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ballenger JC, Post RM. Kindling as a model for alcohol withdrawal syndromes. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:1-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 350] [Cited by in RCA: 295] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Albrecht J. Roles of neuroactive amino acids in ammonia neurotoxicity. J Neurosci Res. 1998;51:133-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gropman AL, Summar M, Leonard JV. Neurological implications of urea cycle disorders. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2007;30:865-879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wszolek ZK, Aksamit AJ, Ellingson RJ, Sharbrough FW, Westmoreland BF, Pfeiffer RF, Steg RE, de Groen PC. Epileptiform electroencephalographic abnormalities in liver transplant recipients. Ann Neurol. 1991;30:37-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Canas N, Breia P, Soares P, Saraiva P, Calado S, Jordão C, Vale J. The electroclinical-imagiological spectrum and long-term outcome of transient periictal MRI abnormalities. Epilepsy Res. 2010;91:240-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Dolman CL, Clasen RA, Dorovini-Zis K. Severe cerebral damage in ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. Clin Neuropathol. 1988;7:10-15. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Harding BN, Leonard JV, Erdohazi M. Ornithine carbamoyl transferase deficiency: a neuropathological study. Eur J Pediatr. 1984;141:215-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kornfeld M, Woodfin BM, Papile L, Davis LE, Bernard LR. Neuropathology of ornithine carbamyl transferase deficiency. Acta Neuropathol. 1985;65:261-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Fichet J, Mercier E, Genée O, Garot D, Legras A, Dequin PF, Perrotin D. Prognosis and 1-year mortality of intensive care unit patients with severe hepatic encephalopathy. J Crit Care. 2009;24:364-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | García-Martínez R, Simón-Talero M, Córdoba J. Prognostic assessment in patients with hepatic encephalopathy. Dis Markers. 2011;31:171-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Glauser T, Shinnar S, Gloss D, Alldredge B, Arya R, Bainbridge J, Bare M, Bleck T, Dodson WE, Garrity L, Jagoda A, Lowenstein D, Pellock J, Riviello J, Sloan E, Treiman DM. Evidence-Based Guideline: Treatment of Convulsive Status Epilepticus in Children and Adults: Report of the Guideline Committee of the American Epilepsy Society. Epilepsy Curr. 2016;16:48-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 808] [Cited by in RCA: 781] [Article Influence: 86.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Vidaurre J, Gedela S, Yarosz S. Antiepileptic Drugs and Liver Disease. Pediatr Neurol. 2017;77:23-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Strozzi I, Nolan SJ, Sperling MR, Wingerchuk DM, Sirven J. Early versus late antiepileptic drug withdrawal for people with epilepsy in remission. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015:CD001902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Summar ML, Dobbelaere D, Brusilow S, Lee B. Diagnosis, symptoms, frequency and mortality of 260 patients with urea cycle disorders from a 21-year, multicentre study of acute hyperammonaemic episodes. Acta Paediatr. 2008;97:1420-1425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |