Published online Nov 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i22.5555

Peer-review started: August 20, 2020

First decision: September 13, 2020

Revised: September 16, 2020

Accepted: October 1, 2020

Article in press: October 1, 2020

Published online: November 26, 2020

Processing time: 97 Days and 14 Hours

The Rex shunt was widely used as the preferred surgical approach for cavernous transformation of the portal vein (CTPV) in children that creates a bypass between the superior mesenteric vein and the intrahepatic left portal vein (LPV). This procedure can relieve portal hypertension and restore physiological hepatopetal flow. However, the modified procedure is technically demanding because it is difficult to make an end-to-end anastomosis of a bypass to a hypoplastic LPV. Many studies reported using a recanalized umbilical vein as a conduit to resolve this problem. However, the feasibility of umbilical vein recanalization for a Rex shunt has not been fully investigated.

To investigate the efficacy of a recanalized umbilical vein as a conduit for a Rex shunt on CTPV in children by ultrasonography.

A total of 47 children who were diagnosed with CTPV with prehepatic portal hypertension in the Second Hospital, Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University, were enrolled in this study. Fifteen children received a recanalized umbilical vein as a conduit for a Rex shunt surgery and were enrolled in group I. Thirty-two children received the classic Rex shunt surgery and were enrolled in group II. The sonographic features of the two groups related to intraoperative and postoperative variation in terms of bypass vessel and the LPV were compared.

The patency rate of group I (60.0%, 9/15) was significantly lower than that of group II (87.5%, 28/32) 7 d after (on the 8th d) operation (P < 0.05). After clinical anticoagulation treatment for 3 mo, there was no significant difference in the patency rate between group I (86.7%, 13/15) and group II (90.6%, 29/32) (P > 0.05). Moreover, 3 mo after (at the beginning of the 4th mo) surgery, the inner diameter significantly widened and flow velocity notably increased for the bypass vessels and the sagittal part of the LPV compared to intraoperative values in both shunt groups (P < 0.05). However, there was no significant difference between the two surgical groups 3 mo after surgery (P > 0.05).

For children with hypoplastic LPV in the Rex recessus, using a recanalized umbilical vein as a conduit for a Rex shunt may be an effective procedure for CTPV treatment.

Core Tip: Recanalized umbilical vein as a conduit for a Rex shunt was recently used to treat cavernous transformation of the portal vein. Fifteen children who received a recanalized umbilical vein as a conduit for a Rex shunt were included in group I, and the remaining 32 children who received a classic Rex shunt were included in group II. There was no difference in patency rate between the two groups after 3 mo of treatments. Diameter and flow velocity of bypass vessels in both two groups increased, and blood flow into the liver of both groups increased 3 mo after surgery.

- Citation: Zhang YQ, Wang Q, Wu M, Li Y, Wei XL, Zhang FX, Li Y, Shao GR, Xiao J. Sonographic features of umbilical vein recanalization for a Rex shunt on cavernous transformation of portal vein in children . World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(22): 5555-5563

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i22/5555.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i22.5555

Cavernous transformation of the portal vein (CTPV) refers to the formation of collateral vessels around the portal vein and is a sequelae of congenital dysplasia in the portal vein that consequently causes portal vein occlusion and portal hypertension[1]. Patients with CTPV tend to suffer from various complications, such as recurrent upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage and hypersplenism[2]. CTPV is the main cause of prehepatic portal hypertension in children[3,4]. It is estimated that approximately 10% of deaths in children with CTPV are due to shock from recurrent upper gastrointestinal bleeding[5].

Surgical intervention for CTPV treatment is difficult because of its irregular courses and the nature of vessels to bleed easily[6]. Traditional treatments for CTPV in children include paraesophagogastric devascularization and portosystemic shunt; however, paraesophagogastric devascularization has a high recurrence rate, and portosystemic shunt presents a high risk of liver damage. Compared to traditional methods, the Rex shunt procedure is a relatively new and effective surgical intervention for CTPV that creates a bypass to bring blood from the superior mesenteric vein to the intrahepatic left portal vein (LPV)[7,8]. The procedure can eliminate prehepatic block, relieve portal hypertension and restore hepatopetal flow[5,9-11]. The Rex shunt was also confirmed to be an effective procedure to improve the prognosis of children with CTPV[12,13]. However, the classic Rex shunt is limited to children for whom the sagittal portion of LPV cannot be easily exposed. For children with hypoplastic LPV in the Rex recessus, the shunt operation is technically demanding because it is difficult to make an end-to-end anastomosis of a bypass graft to a hypoplastic LPV[14]. Therefore, many studies have reported cases using a recanalized umbilical vein as a conduit for a Rex shunt to avoid this challenge[14,15]. However, the feasibility of a recanalized umbilical vein as a conduit for a Rex shunt in children with CTPV has not been fully investigated yet.

In the present study, we retrospectively evaluated the efficacy of a recanalized umbilical vein as a conduit for a Rex shunt in children with CTPV by ultrasonography after surgical treatment. Ultrasonography has been demonstrated to be a reliable tool for CTPV evaluation[16,17]. Our study aimed to find meaningful data of surgical treatments for CTPV.

Between March 2010 and March 2019, 47 children who were diagnosed with CTPV with portal hypertension by preoperative ultrasonography or computed tomography and received a Rex shunt in the Second Hospital, Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University, were enrolled. Among them, 15 children who received a recanalized umbilical vein as a conduit for a Rex shunt were enrolled in group I, including 10 boys and 5 girls aged 6 to 18 years (median age was 9.7 years). The bypass vessels included eight splenic veins, five gastric coronal veins and two internal jugular veins. The remaining 32 children who received a classic Rex shunt were enrolled in group II, including 18 boys and 14 girls aged 3 to 18 years (median age: 7.3 years). The bypass vessels included 18 splenic veins, 10 gastric coronary veins, 2 internal jugular veins and 2 great saphenous veins. Inclusion criteria were that the bypass vessels and the sagittal part of LPV were clearly observed by ultrasound after surgery; otherwise, they were excluded. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Second Hospital, Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University. Informed consent was obtained from each patient’s guardian.

Color Doppler ultrasonography was performed using a GE LOGIQ E9 ultrasound system and convex array probe (C1-5, 2-5 MHz, General Electric, United States). The inner diameter of the bypass vessel was detected on the longitudinal section. When measuring flow velocity, the angle between the long axis of vessels and the Doppler beams was < 60°.

All the children fasted for more than 6 h before the examination. The examination was performed while the child was in supine position, and to stay in calm, drugs were used if necessary to help him/her fall asleep. The ultrasound examination was performed by the same senior radiologist to avoid the interobserver variation.

The Rex shunt was considered a success when the shunt had sufficient patency, and postoperative hepatic function was maintained at the Child-Pugh A level for 3 mo[2]. Therefore, the detection indexes of two groups were compared 3 mo after the operation. The detection indexes were as follows: The inner diameter of bypass vessels and the sagittal part of LPV measured by conventional grayscale ultrasound; the flow filling and direction of blood in the sagittal part of the LPV, and the bypass vessels were observed by color Doppler flow imaging (CDFI); the spectral shape was observed by pulse Doppler; and the flow velocities were measured at the sagittal part of LPV and the middle segment of the bypass vessels.

SPSS software (version 22.0) was applied for statistical analysis. Continuous variables were presented as the mean ± standard deviation, and their normal distribution was analyzed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. According to the results of the normal distribution test, t test (normally distributed data) was used to compare the differences of the data during and after operation in group I and group II. Categorical data were presented as the number (percentage), and their difference was analyzed using the Chi-square (χ2) test or Fisher’s exact test. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

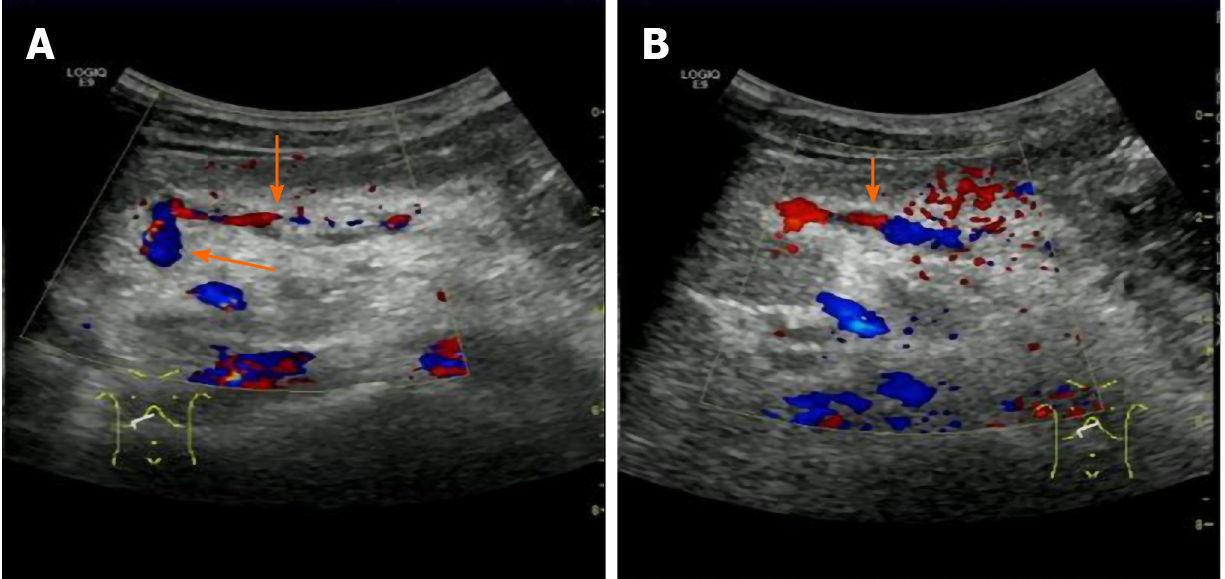

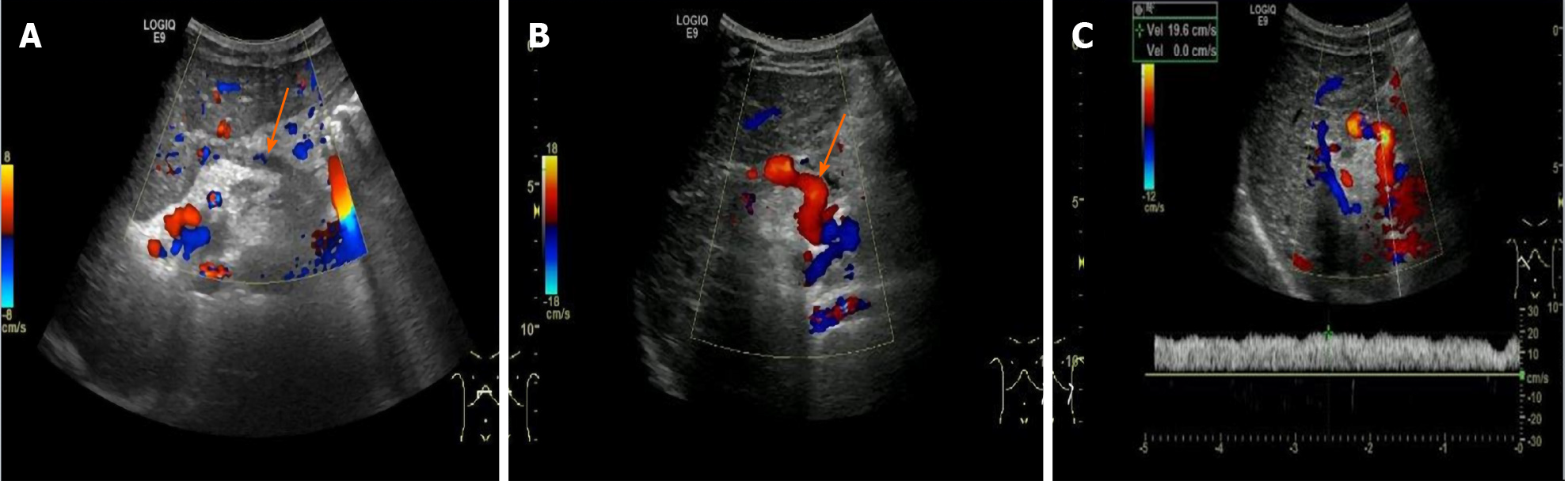

Table 1 shows the patency of the bypass vessels. Seven days after (on the 8th d) surgery, CDFI showed intermittent (Figure 1) or stellate blood flow signals (Figure 2) in the bypass vessels of four children in group I and one child in group II. Moreover, CDFI of two children in group I and three children in group II showed no blood flow signals (Figure 3) in the bypass vessels. These data suggested poor patency of the bypass vessels. The patency rate of group I (60.0%, 9/15) was significantly lower than that of group II (87.5%, 28/32) (P = 0.032).

| Group | Time | Thrombosis | Patency | P value |

| I | At 7 d after operation | 40.0% (6/15) | 60.0% (9/15) | 0.032 |

| II | 12.5% (4/32) | 87.5% (28/32) | ||

| I | At 3 mo after operation | 13.3% (2/15) | 86.7% (13/15) | 0.642 |

| II | 9.4% (3/32) | 90.6% (29/32) |

After clinical anticoagulation treatment for 3 mo, CDFI showed continuous blood flow signals of the bypass vessels (means improved patency) and in color of red (prompts blood flow towards the liver) of five children with intermittent or stellate blood flow signals in bypass vessels before. Moreover, no thrombosis was found in these cases after reperfusion until 1 year after surgery. However, in the other five patients without blood flow signals in the bypass vessels, blood flow signals were still not found after anticoagulation treatment, which means that the bypass vessels remained blocked. There was no significant difference in the patency rate between group I (86.7%, 13/15) and group II (90.6%, 29/32) (P = 0.642).

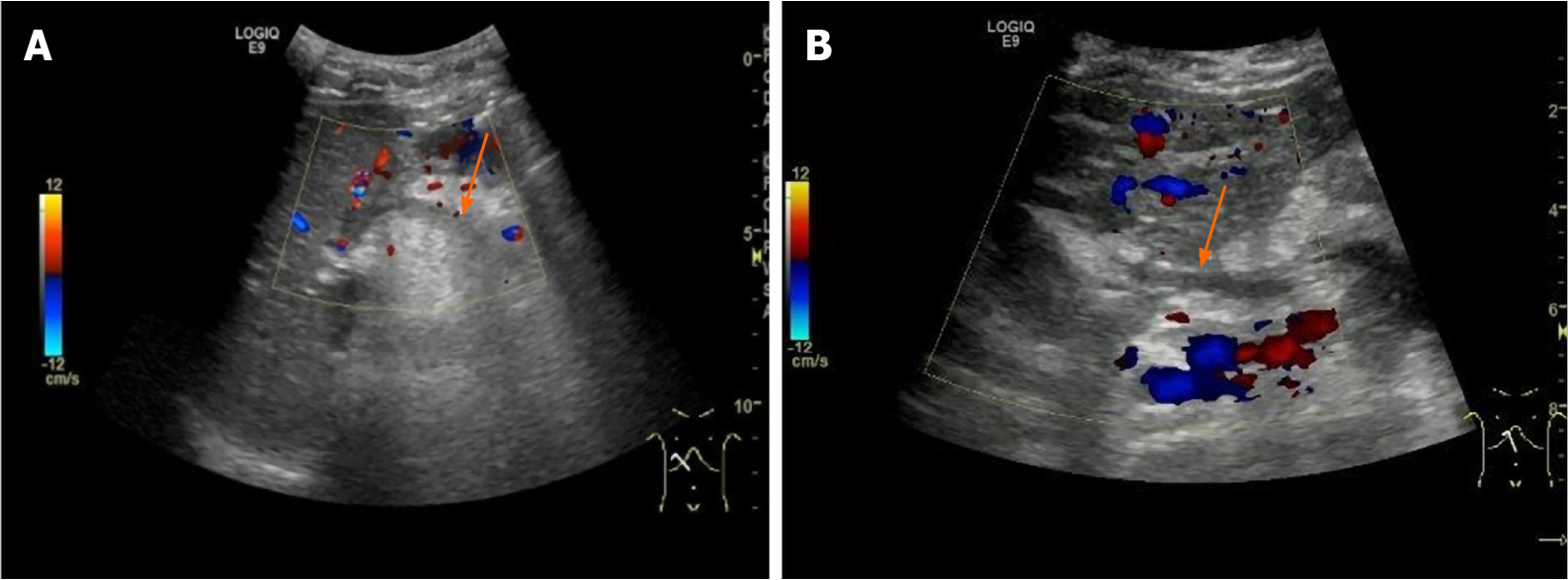

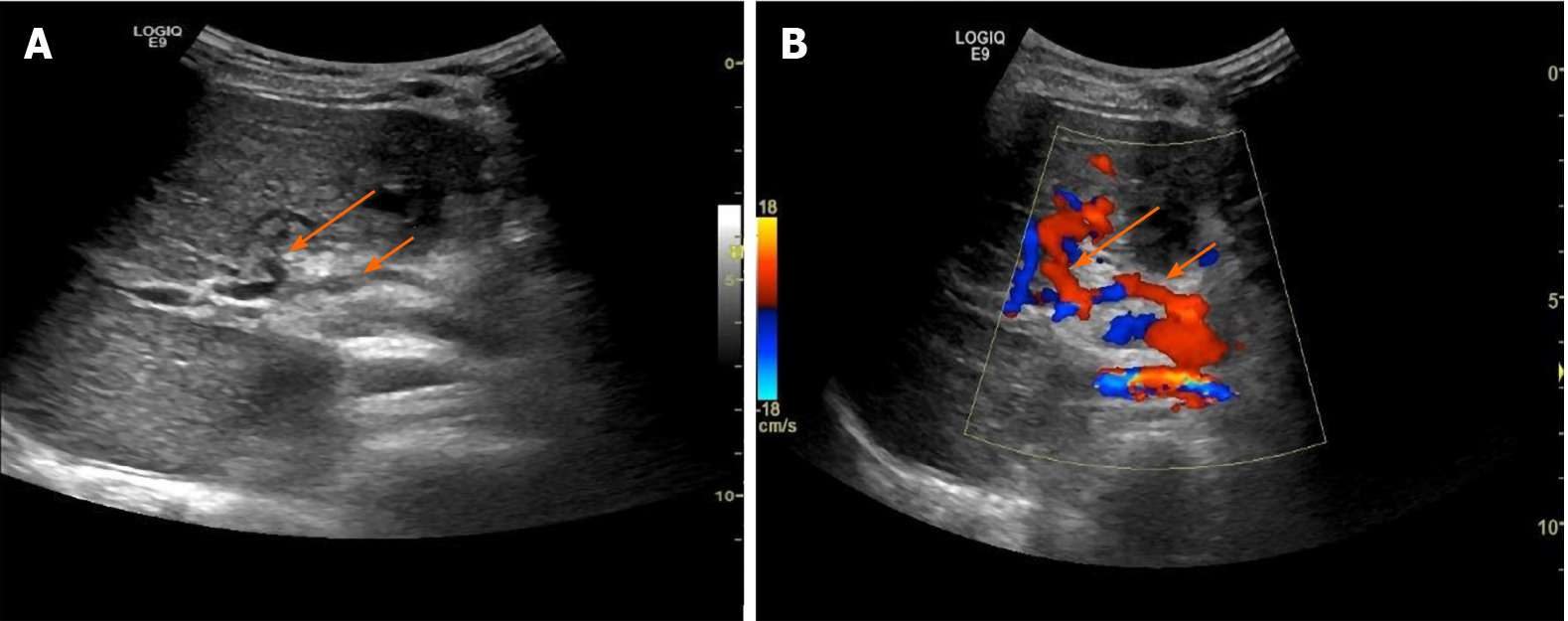

The inner diameter and flow velocity of bypass vessels in both groups increased 3 mo after operation (Table 2). Measurements of the inner diameter and flow velocity of bypass vessels were useful for evaluating the patency of bypass vessels. Postoperative ultrasonic imaging of bypass vessels were clear (Figure 4). The inner diameter significantly widened, and the flow velocity of the bypass vessels increased 3 mo after surgery compared with those values during surgery in both groups (P < 0.05).

| Time | Inner diameter in mm | Flow velocity in cm/s | ||

| Group I | Group II | Group I | Group II | |

| During operation | 5.01 ± 0.71 | 5.13 ± 0.32 | 14.81 ± 2.40 | 15.21 ± 1.83 |

| At 3 mo after operation | 5.47 ± 0.56 | 5.40 ± 0.56 | 16.85 ± 2.75 | 16.57 ± 2.61 |

| P value | 0.038 | 0.042 | 0.015 | 0.046 |

The blood flow into the liver in both groups increased 3 mo after operation (Table 3). The intraoperative and postoperative inner diameter and flow velocity of the sagittal part of the LPV were also measured to evaluate the blood flow into the liver. Three months after operation, we found that the inner diameter dramatically widened and flow velocity increased in the sagittal part of the LPV compared to those during operation in both groups (P < 0.001).

| Time | Inner diameter in mm | Flow velocity in cm/s | ||

| Group I | Group II | Group I | Group II | |

| During operation | 2.56 ± 0.43 | 2.42 ± 0.38 | 10.12 ± 2.37 | 9.73 ± 1.98 |

| At 3 mo after operation | 3.64 ± 0.57 | 3.70 ± 0.73 | 13.41 ± 1.89 | 13.12 ± 2.41 |

| P value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

The incidence of the inner diameter widening and flow velocity increase of bypass vessels and LPV were shown in Table 4. Specifically, in group I the bypass vessel inner diameter widened in 12 cases (80.0%), and the flow velocity increased in 10 cases (66.7%) over time. In group II, the bypass vessel inner diameter widened in 27 cases (84.3%), and the flow velocity increased in 23 cases (71.9%) over time. There was no significant difference between the two groups (P > 0.05). The inner diameter of the sagittal part of LPV widened in 12 cases (80.0%) in group I and 28 cases (87.5%) in group II, and the flow velocity increased in 11 cases (73.3%) in group I and 25 cases (78.1%) in group II. There were no significant differences between the two groups (P > 0.05).

| Outcome | Group I | Group II | P value |

| Incidence of inner diameter widening of bypass vessels | 80.0 (12/15) | 84.3 (27/32) | 1.000 |

| Incidence of flow velocity increase of bypass vessels | 66.7 (10/15) | 71.9 (23/32) | 0.983 |

| Incidence of inner diameter widening of left portal vein | 80.0 (12/15) | 87.5 (28/32) | 0.664 |

| Incidence of flow velocity increase of left portal vein | 73.3 (11/15) | 78.1 (25/32) | 1.000 |

CTPV is a relatively rare vascular deformity that is more commonly found in children. Complete or partial portal vein obstruction is a major cause of prehepatic portal hypertension in CTPV children[18]. The Rex bypass shunt is considered the gold-standard strategy[19], and it restores splanchnic venous blood circulation by creating a bypass vessel to direct blood flow from the LPV into the liver, thereby effectively reducing portal hypertension[20]. However, for children whose LPV is buried deep in the liver or children with LPV dysplasia, the liver tissue wound at the Rex recess could be larger and the anastomosis effect will be quite poor after operation.

During fetal development, the umbilical vein is used to shunt oxygenated umbilical cord blood to the LPV. Using the already connected umbilical vein for a meso-Rex bypass with a single anastomosis can restore hepatopetal perfusion and inflow of hepatotrophic substances thus reducing extrahepatic portal hypertension and its sequelae. The umbilical vein can be anastomosed to the superior mesenteric vein after mechanical dilatation thus maintaining its natural continuation with the LPV[21]. Facciuto et al[21] used a recanalized umbilical vein as a conduit for meso-Rex bypass and achieved decompression of the splanchnic venous system in three children with extrahepatic portal vein obstruction. Shinkai et al[14] reported the use of a recanalized umbilical vein as a conduit for bypass construction in two patients with extrahepatic portal vein obstruction and demonstrated that this method could restore intrahepatic portal vein perfusion. Additionally, a previous study showed that the Rex shunt has a 91% success rate and can remarkably improve gastrointestinal bleeding[2]. Chaves et al[22] conducted pre- and postoperative imaging of the meso-Rex bypass in children and young adults and demonstrated that bypass thrombosis was ribboned on computed tomography and typically hypoechoic on ultrasound. Chen et al[23] performed duplex sonographic evaluation of the meso-Rex bypass and detected acute thrombosis of the graft (no blood flow) in two patients on postoperative days 1 and 40. However, at present there are no reports of ultrasound application in postoperative observation of a recanalized umbilical vein as a conduit for the Rex shunt.

Postoperative bypass occlusion due to thrombosis is the most common complication of the Rex operation and the main complication resulting in surgical failure[22]. The patency of bypass blood vessels is an important indicator for the prognosis of Rex surgery. The patency of bypass blood vessels is consistent with platelet count and changes in esophageal and gastric varices under gastroscopy[24]. In this study, a small proportion of children whose postoperative bypass vessels could not be clearly visualized were not included in this study. Therefore, it is highly recommended to use computed tomography angiography for diagnosis in the clinic. Moreover, we found that thrombosis was more likely to occur in group I (recanalized umbilical vein as a conduit for the Rex shunt) than in group II on postoperative day 8 (7 d after surgery), but there was no significant difference in the total bypass vessel patency rate between the two groups 3 mo after surgery. The reason may be that although the liver round ligament may undergo reconstruction after birth, the layered structure of the medial membrane in the vascular wall remains intact histologically and no significant intimal hyperplasia was observed. On postoperative day 8, thrombosis formation may be related to the tendency of early umbilical cord blood vessels to spasm. After clinical treatment, the vasospasm was relieved, and the bypass vessels were easily recanalized. Thus, it has been recommended that a stent was routinely implanted with the midpoint at the anastomotic site, such that its proximal end was located in the umbilical portion of the LPV[25]. In this study, the safe length of the umbilical vein recommended by Yamanaka et al[26] was 3 cm for surgical recanalization as a conduit for the Rex shunt. This length could effectively prevent thrombosis because of the overlength umbilical vein.

Furthermore, Pokrovsky et al[27] reported that the bypass blood vessels dilate over time. In our study, the inner diameter of bypass vessels widened, and the blood flow velocity of the bypass vessels increased 3 mo after operation compared to those data during operation, which is consistent with the previous study. Additionally, there were no significant differences in the widened inner diameter and increased flow velocity of bypass vessels between the two groups indicating that the efficacy of using a recanalized umbilical vein as a conduit for a Rex shunt surgery is consistent with that of classic Rex surgery. On the other hand, Superina et al[28] confirmed that the recovery of portal vein blood flow into the liver not only reversed the symptoms of portal hypertension but also enhanced liver growth and synthesis function. Our results showed that the inner diameter dramatically widened and the flow velocity increased 3 mo after operation in the sagittal part of the LPV compared to those during operation, and no significant difference existed between the two groups. These data indicated that both two types of Rex surgery had favorable prognosis.

The present study used ultrasonography after surgical treatment to evaluate the efficacy of a recanalized umbilical vein as a conduit for a Rex shunt to treat CTPV in children, providing an effective reference for surgery. Although all measurements were taken by experienced physicians, measurement bias still cannot be entirely avoided. Moreover, the small simple size in the group with a recanalized umbilical vein might interfere with analysis of the overall data, resulting in statistical deviation. Last, the application of ultrasound was only a preliminary exploration, and it is still necessary to summarize and improve ultrasonic detection methods and conduct longer follow-up studies to inform postoperative evaluation of the efficacy of a recanalized umbilical vein as a conduit for a Rex shunt.

Thrombosis is likely to occur early after surgery in group I; however, after a clinically conservative treatment, most bypass thrombosis can be recanalized. Compared with group II, the total patency rate is not significantly different. Moreover, the inner diameter widened and the flow velocity increased for the sagittal part of LPV after surgery in group I, increasing the blood flow into the liver and consequently relieving extrahepatic portal hypertension. In group II, it had a consistent prognosis. For children with a hypoplastic LPV in the Rex recessus, using recanalized umbilical for bypass may be an effective procedure to treat CTPV. Due to its noninvasive, simple and nonradiative advantages, ultrasonography is an important tool to evaluate the prognosis of a recanalized umbilical vein for the treatment of CTPV in children.

The Rex shunt can restore hepatopetal flow and relieve portal hypertension by creating a bypass from the superior mesenteric vein to the intrahepatic left portal vein (LPV) in children with cavernous transformation of the portal vein (CTPV). Compared to traditional surgery, the problem of high risks of recurrence and liver damage can be better resolved. However, the improved shunt with an alternative conduit is technically demanding due to its difficulty in end-to-end anastomosis between a bypass graft and a hypoplastic LPV in the Rex recessus. Nevertheless, the feasibility of a recanalized umbilical vein as a replaceable conduit for a Rex shunt in pediatric patients with a hypoplastic LPV has not been fully explored.

We retrospectively studied the application of a Rex shunt with a recanalized umbilical vein for the treatment of pediatric CTPV along with a postoperative evaluation by ultrasonography to provide useful evidence for the surgical option.

To investigate the efficacy of a recanalized umbilical vein as a conduit for a Rex shunt on CTPV in children using ultrasonography.

A total of 47 children who were diagnosed with CTPV with portal hypertension were enrolled, including 15 children who received a recanalized umbilical vein as a conduit for a Rex shunt (group I), and 32 children received the classic Rex shunt (group II). The pre- and postoperative ultrasonic results associated with prognosis were compared between the two groups.

The Rex shunt with a recanalized umbilical vein achieved a similar postoperative outcome to the classic Rex shunt, confirming the availability of this modified procedure.

The improved Rex shunt using a recanalized umbilical vein was an effective approach to treat CTPV in children with a hypoplastic LPV. Meanwhile, ultrasonography can be a reliable imaging modality for the assessment of surgical results.

In this study, we focused on the feasibility of this modified Rex procedure in the treatment of pediatric CTPV. However, further long-term follow-up remains to be performed.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Radiology, Nuclear Medicine and Medical Imaging

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kastelein F, Sharma P S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Nasim M, Majid B, Tahir F, Majid Z, Irfan I. Cavernous Transformation of Portal Vein in the Setting of Protein C and Anti-thrombin III Deficiency. Cureus. 2019;11:e5779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wang RY, Wang JF, Sun XG, Liu Q, Xu JL, Lv QG, Chen WX, Li JL. Evaluation of Rex Shunt on Cavernous Transformation of the Portal Vein in Children. World J Surg. 2017;41:1134-1142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Young V, Rajeswaran S. Management of Portal Hypertension in the Pediatric Population: A Primer for the Interventional Radiologist. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2018;35:160-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lv Y, He C, Guo W, Yin Z, Wang J, Zhang B, Meng X, Cai J, Luo B, Wu F, Niu J, Fan D, Han G. Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt for Extrahepatic Portal Venous Obstruction in Children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;62:233-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wang RY, Wang JF, Liu Q, Ma N, Chen WX, Li JL. Combined Rex-bypass shunt with pericardial devascularization alleviated prehepatic portal hypertension caused by cavernomatous transformation of portal vein. Postgrad Med. 2017;129:768-776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chawla YK, Bodh V. Portal vein thrombosis. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2015;5:22-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Stenger AM, Broering DC, Gundlach M, Bloechle C, Ganschow R, Helmke K, Izbicki JR, Burdelski M, Rogiers X. Extrahilar mesenterico-left portal shunt for portal vein thrombosis after liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2001;33:1739-1741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wei Z, Rui SG, Yuan Z, Guo LD, Qian L, Wei LS. Partial splenectomy and use of splenic vein as an autograft for meso-Rex bypass: a clinical observational study. Med Sci Monit. 2014;20:2235-2242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | AteÅŸ O, Hakgüder G, Olguner M, Seçil M, Karaca I, Akgür FM. Mesenterico left portal bypass for variceal bleeding owing to extrahepatic portal hypertension caused by portal vein thrombosis. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:1259-1263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lautz TB, Keys LA, Melvin JC, Ito J, Superina RA. Advantages of the meso-Rex bypass compared with portosystemic shunts in the management of extrahepatic portal vein obstruction in children. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216:83-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dasgupta R, Roberts E, Superina RA, Kim PC. Effectiveness of Rex shunt in the treatment of portal hypertension. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:108-12; discussion 108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | de Ville de Goyet J, D'Ambrosio G, Grimaldi C. Surgical management of portal hypertension in children. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2012;21:219-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cortez AR, Kassam AF, Jenkins TM, Nathan CJ, Nathan JD, Alonso MH, Ryckman FC, Tiao GM, Bondoc AJ. The role of surgical shunts in the treatment of pediatric portal hypertension. Surgery. 2019;166:907-913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Shinkai M, Ohhama Y, Honda S, Kitagawa N, Mochizuki K, Take H, Hirata Y, Usui Y, Shibasaki J, Ueda H, Aida N. Recanalized umbilical vein as a conduit for mesenterico/porto-Rex bypass for patients with extrahepatic portal vein obstruction. Pediatr Surg Int. 2011;27:315-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Shinkai M, Mochizuki K, Kitagawa N, Take H, Usui H, Yamoto KN, Fujita S, Ohhama Y. Usefulness of a recanalized umbilical vein for vascular reconstruction in pediatric hepatic surgery. Pediatr Surg Int. 2016;32:553-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kessler A, Graif M, Konikoff F, Mercer D, Oren R, Carmiel M, Blachar A. Vascular and biliary abnormalities mimicking cholangiocarcinoma in patients with cavernous transformation of the portal vein: role of color Doppler sonography. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:1089-1095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hwang M, Thimm MA, Guerrerio AL. Detection of cavernous transformation of the portal vein by contrast-enhanced ultrasound. J Ultrasound. 2018;21:153-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kuy S, Dua A, Rieland J, Cronin DC 2nd. Cavernous transformation of the portal vein. J Vasc Surg. 2016;63:529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Superina R, Shneider B, Emre S, Sarin S, de Ville de Goyet J. Surgical guidelines for the management of extra-hepatic portal vein obstruction. Pediatr Transplant. 2006;10:908-913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhao H, Tsauo J, Zhang X, Li X. Regarding "The optimal procedure of modified Rex shunt for the treatment of extrahepatic portal hypertension in children". J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2018;6:421-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Facciuto ME, Rodriguez-Davalos MI, Singh MK, Rocca JP, Rochon C, Chen W, Katta US, Sheiner PA. Recanalized umbilical vein conduit for meso-Rex bypass in extrahepatic portal vein obstruction. Surgery. 2009;145:406-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Chaves IJ, Rigsby CK, Schoeneman SE, Kim ST, Superina RA, Ben-Ami T. Pre- and postoperative imaging and interventions for the meso-Rex bypass in children and young adults. Pediatr Radiol. 2012;42:220-32; quiz 271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chen W, Rodriguez-Davalos MI, Facciuto ME, Rachlin S. Experience with duplex sonographic evaluation of meso-rex bypass in extrahepatic portal vein obstruction. J Ultrasound Med. 2011;30:403-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ruan Z, Wu M, Shao C, Zhang Y, Zhang C, Zhang F, Zhao B. Effects of Rex-bypass shunt on the cavernous transformation of the portal vein in children: evaluation by the color Doppler ultrasonography. Insights Imaging. 2020;11:4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chen CL, Cheng YF, Huang V, Lin TL, Chan YC, Ou HY, Yong CC, Wang SH, Lin CC. P4 Stump Approach for Intraoperative Portal Vein Stenting in Pediatric Living Donor Liver Transplantation: An Innovative Technique for a Challenging Problem. Ann Surg. 2018;267:e42-e44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yamanaka N, Yasui C, Yamanaka J, Tanaka T, Ando T, Kuroda N, Okamoto E. Recycled use of reopened umbilical vein for venous reconstruction in hepatopancreatobiliary surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;190:497-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Pokrovsky AV, Ignat'ev IM, Gradusov EG. [Remote results of veno-venous bypass operations in post-thrombotic disease]. Angiol Sosud Khir. 2016;22:91-98. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Superina R, Bambini DA, Lokar J, Rigsby C, Whitington PF. Correction of extrahepatic portal vein thrombosis by the mesenteric to left portal vein bypass. Ann Surg. 2006;243:515-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |