Published online Aug 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i15.3284

Peer-review started: December 25, 2019

First decision: March 27, 2020

Revised: May 15, 2020

Accepted: July 22, 2020

Article in press: July 22, 2020

Published online: August 6, 2020

Processing time: 224 Days and 18.9 Hours

Because of atypical clinical symptoms, lymphoma is easily confused with infectious diseases. Extranodal nasal-type natural killer/T-cell lymphoma (NKTL) is more common, and there are few cases of eyelid site onset and intracranial infiltration, which increases the difficulty of diagnosis. This disease usually has a very poor prognosis and there are few reports of recovery.

A 3-year-old boy was admitted to our hospital due to an initial misdiagnosis of "eyelid cellulitis" and failed antibiotic treatment. He was characterized by fever, right eyeball bulging, convulsions, and abnormal liver function. His blood Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) DNA was positive (8.798 × 104 copies/mL), and remained positive for about half a year. The cranial imaging examination suggested a space-occupying lesion in the right eyelid, with the right temporal lobe and meninges involved. The boy underwent ocular mass resection. The pathological diagnosis was NKTL. He was diagnosed as having NKTL with intracranial infiltration, combined with chronic active EBV infection (CAEBV). Then he underwent systemic chemotherapy and intrathecal injection. The boy suffered from abnormal blood coagulation, oral mucositis, diarrhea, liver damage, and severe bone marrow suppression but survived. Finally, the tumor was completely relieved and his blood EBV-DNA level turned negative. The current follow-up has been more than 2 years and his condition is stable.

This case suggests that chemotherapy combined with intrathecal injection may have a good effect on intracranial infiltrating lymphoma and CAEBV, which deserves further study and discussion.

Core tip: Natural killer/T-cell lymphoma (NKTL) is rare to see with the eyelid site onset and intracranial infiltration, which increases the difficulty of diagnosis and suggests a very poor prognosis. We present the case of a 3-year-old boy who was initially misdiagnosed with ocular cellulitis but finally diagnosed with NKTL with ocular involvement, intracranial infiltration, and chronic active Epstein-Barr virus infection. He achieved complete remission through chemotherapy. Ocular involvement and intracranial infiltration are rare in NKTL cases and are associated with a poor prognosis, but the boy responded well to chemotherapy, which deserves further study and discussion.

- Citation: Li N, Wang YZ, Zhang Y, Zhang WL, Zhou Y, Huang DS. Natural killer/T-cell lymphoma with intracranial infiltration and Epstein-Barr virus infection: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(15): 3284-3290

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i15/3284.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i15.3284

Mature natural killer/T-cell lymphoma (NKTL) shows a high prevalence in children and adolescents in Central and South American and Asian populations, with many cases being associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection. However, the genetic basis remains unknown[1]. NKTL shows atypical clinical symptoms that are easily confused with infectious diseases, leading to delays in diagnosis. EBV infection-associated NKTL with orbital and intracranial infiltration is rare, which increases the difficulty of diagnosis and has a poor prognosis. We report here a misdiagnosed case of chemotherapy-sensitive EBV-associated NKTL with intracranial infiltration.

A 3-year-old boy was admitted to our hospital complaining of intermittent fever with a protruding right eye for more than 1 mo.

In the preceding month, despite no obvious cause of fever, a peak body temperature of 39.2 °C was recorded, with right eyelid swelling and progressive aggravation. He was taken to a local hospital and anti-infection treatments were given but failed, following which the boy was admitted to our hospital.

The boy had a free previous medical history and his growth and development were normal.

Several enlarged lymph nodes could be touched on both sides of the submandibular and in front of the ear, up to about 1.5 cm × 1.5 cm, without obvious tenderness. The right orbit was markedly red and swollen, and the right eyelid was swollen and valgus, covering part of the eyeball. No other abnormal findings were found.

Routine blood tests showed a normal white blood cell count, mainly lymphocytes; significantly increased liver function indexes; EBV early antigen IgG positivity; and EBV viral capsid antigen IgM positivity. His blood EBV-DNA was positive (8.798 × 104 copies/mL) and remained positive for about half a year. Immunodeficiency gene test showed that the interleukin-2-inducible T-cell kinase (ITK) gene of the boy and his mother had a heterozygous mutation of c.1741C>T/p. R581W, and the father was normal. But no abnormalities were found in electrocardiogram and other laboratory examinations.

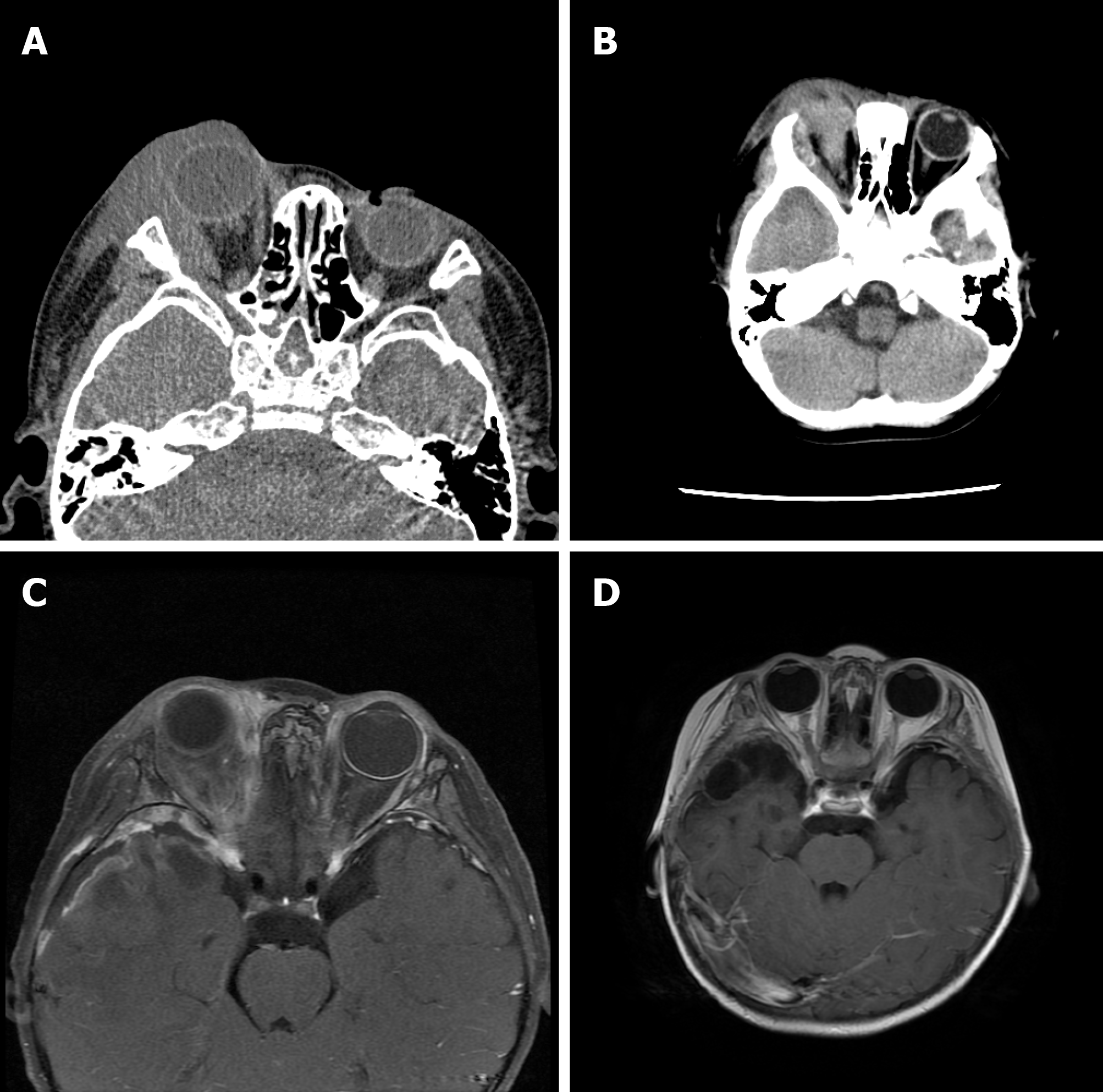

An initial imaging evaluation by eyelid computed tomography (CT, Figure 1A) at the local hospital showed abnormal signals in the right rectus muscle, right lacrimal gland, and right eyelid, and no abnormalities were found in chest X-ray.

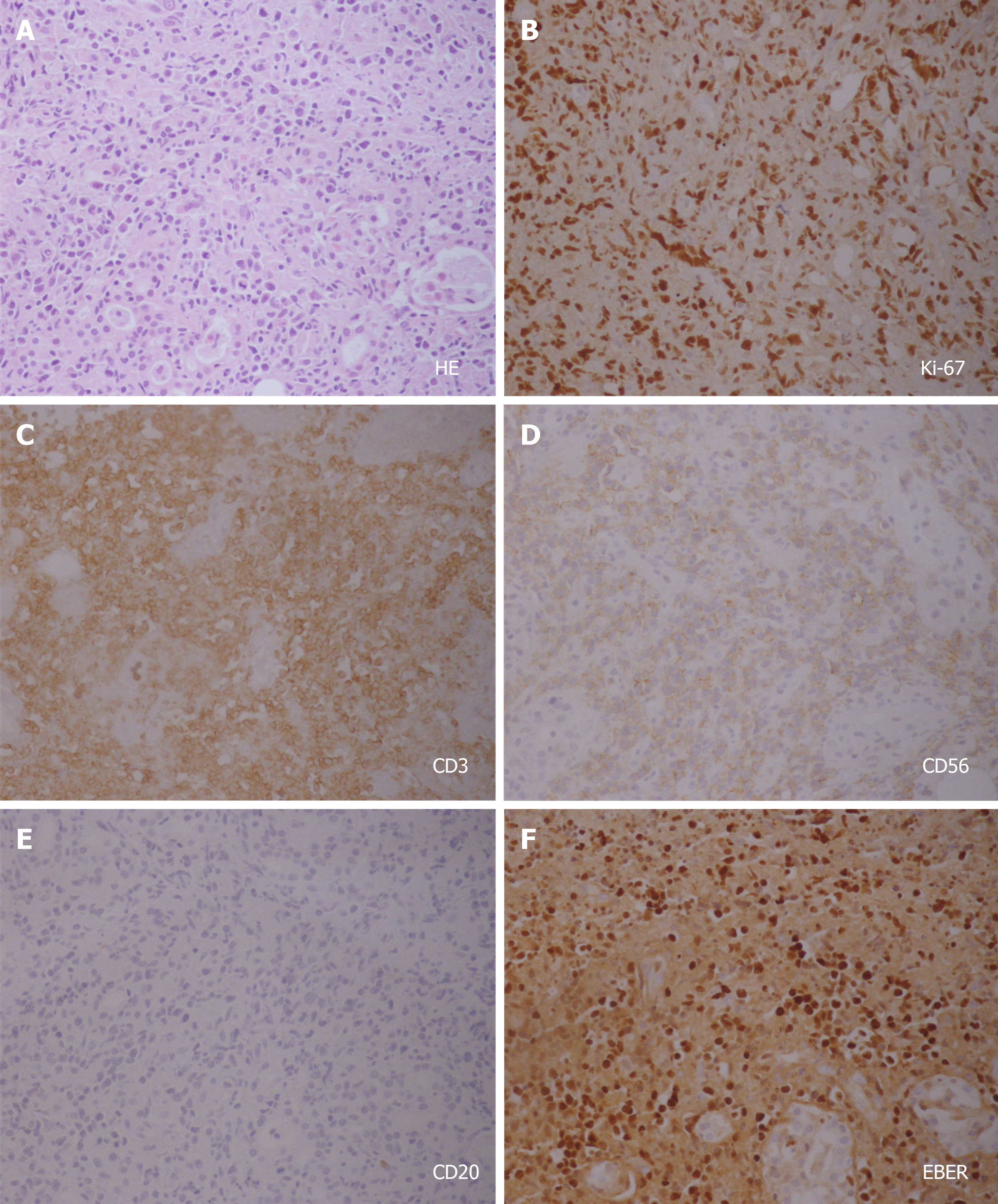

Since this boy was suggested with EBV infection, we used intravenous ganciclovir antiviral therapy, but his body temperature did not improve, and his eye protrusion was further aggravated. The boy then underwent ocular mass resection. Frozen pathology indicated the possibility of rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS). On the second postoperative day, the boy suffered two episodes of convulsions. A CT scan (Figure 1B) showed that the lesion range had increased, involving the temporal lobe. The AVCP chemotherapy regimen was initiated to actively control the disease, in line with the RMS pathology results. Immunohistochemistry showed LCA+, CD99-, CD2+, CD5-, CD20-, CD3+, CD43-, CD79a-, CD38+, PAX-5-, CD138-, CgA-, Syn-, CD56+, CD4-, CD7-, CD30-, CD21-, CD8+ > CD4+, TdT-, CD1a-, MyoD1-, Myogenin-, TIA 1+, GrB+, P53-, Performin-, EBER+, and a Ki-67 index of 80% (Figure 2). A final pathological diagnosis of NKTL was made at our hospital and the other famous hospital, but the other hospital pathology consultation considered EBV-positive T-cell lymphoid tissue proliferative disease, grade III (tumor stage).

The final diagnosis of the presented case was NKTL with intracranial infiltration and chronic EBV infection.

Over the following 3 mo, the boy underwent two cycles of SMILE chemotherapy (ifosfamide 1.5 g/m2, days 2-5; etoposide 75 mg/m2, days 2-5; pegaspargase 2500 IU/m2, day 1; methotrexate 2 g/m2, day 1; methylprednisolone 40-60 mg/m2, days 1-5) and one cycle of VIPD (ifosfamide 1.2 g/m2, days 1-3; etoposide 100 mg/m2, days 2-3; cisplatin 33 mg/m2, days 1-3; dexamethasone 15 mg/m2, days 1-4). Lumbar puncture with intrathecal injection of chemotherapy drugs (dexamethasone 5 mg, cytarabine 25 mg, and methotrexate 10 mg) was also given weekly. The boy’s body temperature gradually decreased to normal, the right eye tumor retracted, and his blood EB-DNA level decreased to 5.765 × 102 copies/mL. Positron emission tomography/CT showed no abnormal fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake in intracranial and orbital lesions, FDG uptake in the cervical lymph nodes was mild, no abnormal FDG uptake was observed in other sites, and complete tumor remission and chronic active EBV infection was considered. In the following months, two cycles of SMILE and one cycle of VIPD chemotherapy were given along with weekly intrathecal injection. His blood EBV-DNA finally turned negative, and brain enhanced nuclear magnetic resonance (Figure 1D) showed no residual lesions (Table 1). The boy recovered from both chronic active EBV infection (CAEBV) and NKTL.

| Before treatment | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Pathology | Frozen pathology: RMS | NKTL | ||||||

| Regimens | Ganciclovir and antibiotic | AVCP | SMILE | SMILE | VIPD | SMILE | SMILE | VIPD |

| Intrathecal injection | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| CSF tests | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | ||

| CSF Flow cytometry | Negative | Negative | ||||||

| CSF-NSE (ng/mL) | 21.7 | 25.5 | 21.4 | 19.7 | 17.1 | 16.2 | ||

| Blood-NSE (ng/mL) | 68.3 | 31.9 | 27.6 | |||||

| LDH (U/L) | 733 | 372 | 354 | 202 | 277 | 221 | 205 | 263 |

| ALT (U/L) | 207 | 113 | 33.3 | 103 | 72 | 22.6 | 76.2 | 46 |

| Blood EB-DNA (copies/mL) | 8.798 × 104 | 7.699 × 104 | 5.765 × 102 | 1.115 × 103 | Negative | |||

| Imaging examination | Eyelid CT and Head CT | Eyelid MRI | PET-CT | Brain enhanced MR-Figure4 | ||||

| Chest X-ray/CT | Normal | PET-CT | Normal | |||||

| Abdominal ultrasound | Normal | Normal | PET-CT | Normal | ||||

| Lymph node ultrasound | Reactive hyperplasia-neck | PET-CT | Reactive hyperplasia-neck | |||||

| Bone marrow | Negative | Negative | Negative | |||||

| Chemotherapy complications | Low fibrinogenemia, oral mucositis, diarrhea, bronchial pneumonia, neutropenia with fever, liver function damage, myocardial damage, and severe myelosuppression | |||||||

After completion of chemotherapy, the parents refused further examination and treatment such as radiation therapy or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Currently, the boy has survived for more than two years without disease.

NKTL with eyelid involvement and intracranial infiltration is rare, and the literature indicates that the prognosis is poor[2,3]. Wang et al[4] reported the case of a 34-year-old man with extranodal nasal-type NKTL involving the middle cranial fossa. He underwent three cycles of chemotherapy and intrathecal injection. Tumor progression was temporarily controlled, but he died of neutropenia and severe infection.

This boy presenting with primary tumor in the eyelid with intracranial infiltration was highly risky, with a potentially extremely poor prognosis. He was treated with systemic chemotherapy and intrathecal injection only, without other treatments such as radiotherapy and transplantation, yet the tumor was completely relieved and the child has survived for 2 years without disease. This suggests that systemic chemotherapy and intrathecal injection may be effective for the treatment of intracranial invasive NKTL. This boy also experienced abnormal blood coagulation, oral mucositis, diarrhea, intermittent fever and liver damage, severe bone marrow suppression, and other abnormalities during the course of chemotherapy, but fortunately he survived and achieved remission.

Another noteworthy issue is the diagnosis of the condition. Owing to significant clinical and pathological overlap, the precise distinction between T/NK-cell lymphoproliferative disorder in children and young adults (TNKLPDC) and other EBV-associated NKTL is difficult to establish. Studies have shown that p53, EZH2, and survivin are similarly highly expressed in both conditions[5]. However, the expression of aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 in TNKLPDC was significantly higher, while the gene overexpressed in advanced malignant tumors was enriched in NKTL. This result is consistent with the different clinical manifestations between these two diseases.

TNKLPDC is a systemic disease with systemic symptoms or abnormal findings, often accompanied by bone marrow involvement and cytopenia, with a long history and gradually increasing aggravation, while NKTL often begins with local lesions, then becomes progressively exacerbated and spreads[6], clinically manifesting as invasive solid tumors. Patients with TNKLPDC can remain stable for many years without treatment, and some CAEBV patients will develop aggressive lymphoma. It is believed that the main clinical finding of CAEBV is inflammation, and CAEBV rarely has solid tumors[7]. The boy in our case had a protruding mass that gradually increased in size. MRI showed a soft tissue mass in the right eyelid with invasive growth and intracranial infiltration. These clinical manifestations of invasive solid tumor, combined with the pathological findings, led to a final diagnosis of NKTL. As mentioned above, the history of TNKLPDC is prolonged and its progression is slow, but this boy showed clinical symptoms of a solid space-occupying tumor shortly after the onset of the disease, so we did not think that there was enough evidence to confirm the clinical progression from TNKLPDC to NKTL. In addition, among the three-level classification proposed by Ohshima, A3 is a monomorphic lymphoproliferative disorder of monoclonal T- or NK cells, and is equivalent to EBV-related T/NK lymphoma/leukemia[8], and in 2016, CAEBV was classified under EBV-positive T- or NK- cell neoplasms in the revised WHO classification of tumors of hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues[7]. Whether the two are worth distinguishing remains inconclusive[9]. The only effective treatment strategy for a cure currently is allo-HSCT. Findings indicate that the effects of allo-HSCT were partially due to the replacement and reconstruction of the hematopoietic and immune systems by allogeneic grafts since immunological dysfunction plays a pivotal role in the development of CAEBV. Although the boy in this case did not receive HSCT, he was relieved by chemotherapy and his blood EBV-DNA turned negative, which is very rare. The reasons are considered as follows. On the one hand, the boy does not have a mutation of a known pathogenic immunodeficiency gene. Although there is a heterozygous mutation in the ITK gene (as described below), the mother who also carries the heterozygous mutation is healthy. Research also suggests that the prognosis of children is generally better than that of adults[7], and we speculate that this may be due to the development of childhood immune function. This case suggests that chemotherapy may have a certain effect. However, although the boy has been disease-free for more than 2 years, it cannot be ruled out that there may be a relapse in the future, and long-term follow-up is required.

Both the boy and his mother displayed a heterozygous mutation in the ITK gene c.1741C>T/p. R581W, which has not been reported in the past. ITK is a member of the Tec kinase family and is currently believed to play an important role in differentially regulating T-cell activation, proliferation, and differentiation, and NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity[9]. Recent studies have found that ITK gene defects may lead to instability of ITK protein, loss of NKT cells, and immune dysfunction, eventually leading to EBV-related hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, B-cell lymphoid hyperplasia with hepatosplenomegaly, or Hodgkin’s lymphoma[10,11], and the prognosis is extremely poor. In this case, the boy presented with EBV-positive NKTL. His mother is in good health, despite the ITK mutation. Unfortunately, we have not been able to perform further examinations, but combined with previous studies, attention should be paid to ITK gene defects in children with EBV-associated lymphoproliferative disorders.

Only scarce reports of NKTL with intracranial infiltration have been reported, which often has a poor prognosis. We suggest that appropriate chemotherapy combined with intrathecal injection may be effective for NKTL with intracranial infiltration and CAEBV. Based on the opinions of the parents of the boy and the reasons for the existing testing conditions, immunostaining for EBNA-2, LMP-1, and the monoclonality of EBV infection in the lymphoma cells was not completed, and there was no further research on ITK gene mutations in our study, which is very regrettable. It is hoped that more studies will explore similar diseases in the future.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Nagasawa M, Saito M S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Pillai V, Tallarico M, Bishop MR, Lim MS. Mature T- and NK-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma in children and young adolescents. Br J Haematol. 2016;173:573-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zuhaimy H, Aziz HA, Vasudevan S, Hui Hui S. Extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma presenting as orbital cellulitis. GMS Ophthalmol Cases. 2017;7:Doc04. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cruz AA, Valera FC, Carenzi L, Chahud F, Barros GE, Elias J. Orbital and central nervous system extension of nasal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;30:20-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wang H, Xia X, Qian C. Extranodal natural killer/T cell lymphoma, nasal type in the middle cranial fossa: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e12028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Park S, Ko YH. Epstein-Barr virus-associated T/natural killer-cell lymphoproliferative disorders. J Dermatol. 2014;41:29-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zhou XG, Zhang YL, Xie JL, Huang YH, Zheng YY, Li WS, Chen H, Liu F, Pan HX, Wei P, Wang Z, Hu YC, Yang KY, Xiao HL, Wu MJ, Yin WH, Mei KY, Chen G, Yan XC, Meng G, Xu G, Li J, Tian SF, Zhu J, Song YQ, Zhang WJ. [The understanding of Epstein-Barr virus associated lymphoproliferative disorder]. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2016;45:817-821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Arai A. Advances in the Study of Chronic Active Epstein-Barr Virus Infection: Clinical Features Under the 2016 WHO Classification and Mechanisms of Development. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ohshima K, Kimura H, Yoshino T, Kim CW, Ko YH, Lee SS, Peh SC, Chan JK; CAEBV Study Group. Proposed categorization of pathological states of EBV-associated T/natural killer-cell lymphoproliferative disorder (LPD) in children and young adults: overlap with chronic active EBV infection and infantile fulminant EBV T-LPD. Pathol Int. 2008;58:209-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zheng F, Li J, Zha H, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Cheng F. ITK Gene Mutation: Effect on Survival of Children with Severe Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis. Indian J Pediatr. 2016;83:1349-1352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Huck K, Feyen O, Niehues T, Rüschendorf F, Hübner N, Laws HJ, Telieps T, Knapp S, Wacker HH, Meindl A, Jumaa H, Borkhardt A. Girls homozygous for an IL-2-inducible T cell kinase mutation that leads to protein deficiency develop fatal EBV-associated lymphoproliferation. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1350-1358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ghosh S, Bienemann K, Boztug K, Borkhardt A. Interleukin-2-inducible T-cell kinase (ITK) deficiency - clinical and molecular aspects. J Clin Immunol. 2014;34:892-899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |