Published online Apr 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i8.992

Peer-review started: December 19, 2018

First decision: January 19, 2019

Revised: February 21, 2019

Accepted: March 26, 2019

Article in press: March 26, 2019

Published online: April 26, 2019

Processing time: 128 Days and 19.5 Hours

Extranodal natural killer (NK) T-cell lymphoma (ENKTL), nasal type is a rare subtype of extranodal non-Hodgkin lymphoma characterized by vascular damage and necrosis. The lesions usually present in the nasal cavity and adjacent tissues, however, the disease originates from the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tract in 25% of cases. Since rectal involvement in ENKTL is rare, rectal symptoms in the course of ENKTL are often misdiagnosed and considered to be related to benign diseases such as rectal fistula or perianal abscess.

We report the case of a 24-year-old Han Chinese female who initially presented with a perianal abscess that was subsequently diagnosed as nasal type ENKTL. Due to typical perianal pain, perianal abscess was diagnosed and surgical incision and drainage were performed. After recurrent, severe anal hemorrhages leading to hypovolemic shock and multiple surgeries, a diagnosis of ENKTL was made. The patient’s condition gradually deteriorated, and she died shortly after initiation of chemotherapy.

Systemic and neoplastic diseases should be included in the differential diagnosis of any potentially benign perianal abscess complicated with recurrent hemorrhages.

Core tip: The case highlights the need to include systemic and neoplastic diseases in the differential diagnosis of any potentially benign perianal abscess complicated with recurrent hemorrhages. A 24-year-old Han Chinese female, initially diagnosed with perianal abscess, underwent the surgical incision and drainage. The symptoms and the results of imaging, laboratory analysis, and colonoscopic biopsy were non-specific. After recurrent, severe anal hemorrhages leading to hypovolemic shock and multiple surgeries, a final diagnosis of extranodal natural killer/T cell lymphoma was made based on the result of histopathological examination. The patient’s condition gradually deteriorated, and she died shortly after initiation of chemotherapy.

- Citation: Liu YN, Zhu Y, Tan JJ, Shen GS, Huang SL, Zhou CG, Huangfu SH, Zhang R, Huang XB, Wang L, Zhang Q, Jiang B. Extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma (nasal type) presenting as a perianal abscess: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(8): 992-1000

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i8/992.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i8.992

Extranodal nasal type NK/T-cell lymphoma (ENKTL), according to the 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms, is a type of invasive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma expressing NK cell (or less frequently T cell) markers. It is a rare disease that accounts for 2%-10% of malignant lymphomas and is most prevalent in Asia and South America[1]. It is most commonly observed in young and middle-aged males and the male to female ratio is about 2-4:1[2]. The nasal cavity is the most common primary site of ENKTL and adjacent tissues are often involved including the skin. Twenty-five percent of cases originate from extranasal tissues, including the gastrointestinal tract, lungs, skin, and testes. There have been only a few reports of ENKTL originating in the anorectal region.

Although the pathogenesis of ENKTL is not fully understood, it has been shown to be closely related to EBV infection[3,4]. The lesions are characterized by vascular invasion and destruction, significant necrosis, expression of cytotoxic molecules (i.e., granzyme B, perforin, and T cell-restricted intracellular antigen-1 [TIA-1]), and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection[5-8]. Typically, the cells are CD2 and CD56 positive, and surface CD3 negative[9-12]. Moreover, they are usually positive for cytotoxic molecules (such as granzyme B, TIA-1, and perforin), and negative for other T and NK cell-associated antigens, including CD4, CD5, CD8, CD16, and CD57[13-15].

While sinonasal ENKTL has a better prognosis than extranasal disease, its course is usually aggressive with rapid progression, and the prognosis is usually poor with a 5-year survival rate of approximately 30%[16] or even lower in more advanced stages[8,17,18]. Due to the non-specific symptoms, the disease is difficult to diagnose. Here we present a case of ENKTL in the rectum initially diagnosed and treated as a perianal abscess.

Anal discomfort for 22 d after surgery and fever for two days.

A 24-year-old female patient was admitted to our hospital for routine perianal abscess incision and drainage surgery. The surgery was performed in January 2016. Thirteen days after the surgery, she was discharged in good condition. Twenty-two days after the discharge, the patient was readmitted to the hospital because of anal discomfort that started just after the discharge. Two days before readmission, the patient developed a fever.

The patient reported no past illnesses.

The patient was previously healthy and her family history was unremarkable.

After admission, the doctor found that apart from a 2 cm surgical wound localized at the 6 o’clock position, a digital rectal examination revealed a prominent 3-4 cm lesion localized laterally from the surgical wound at the 7 o’clock position and extending upwards to the 11 o’clock position. Blood was present in the stool.

Routine laboratory analysis showed leukocytosis with neutrophilia (white blood cells 16.12 × 109/L, 81.91% neutrophils); increased levels of inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein: 15.2 mg/L; prealbumin: 106.00 mg/L; albumin: 30.60 g/L; total protein: 48.20 g/L), cholinesterase (111.00 U/L), and creatine kinase (21.00 U/L).

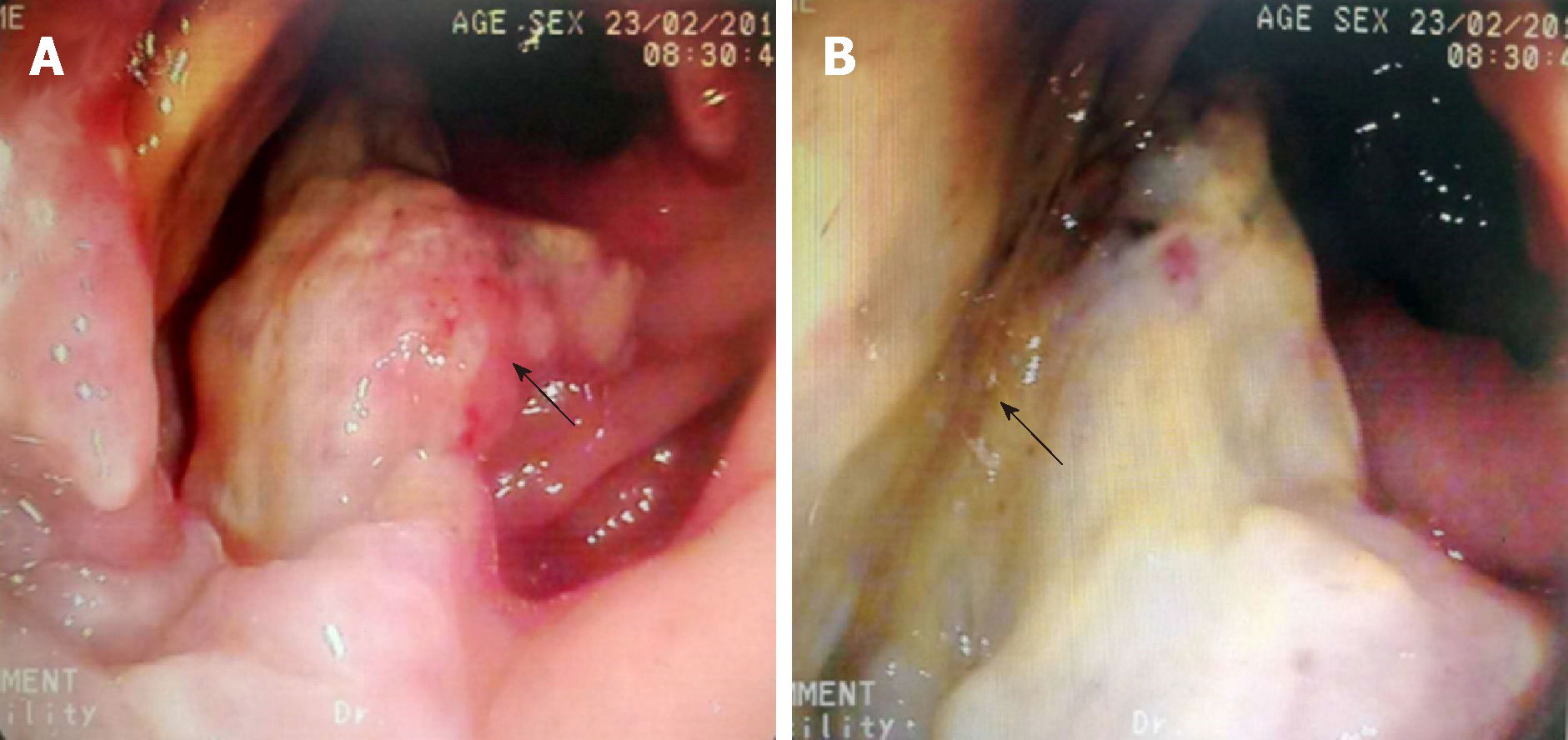

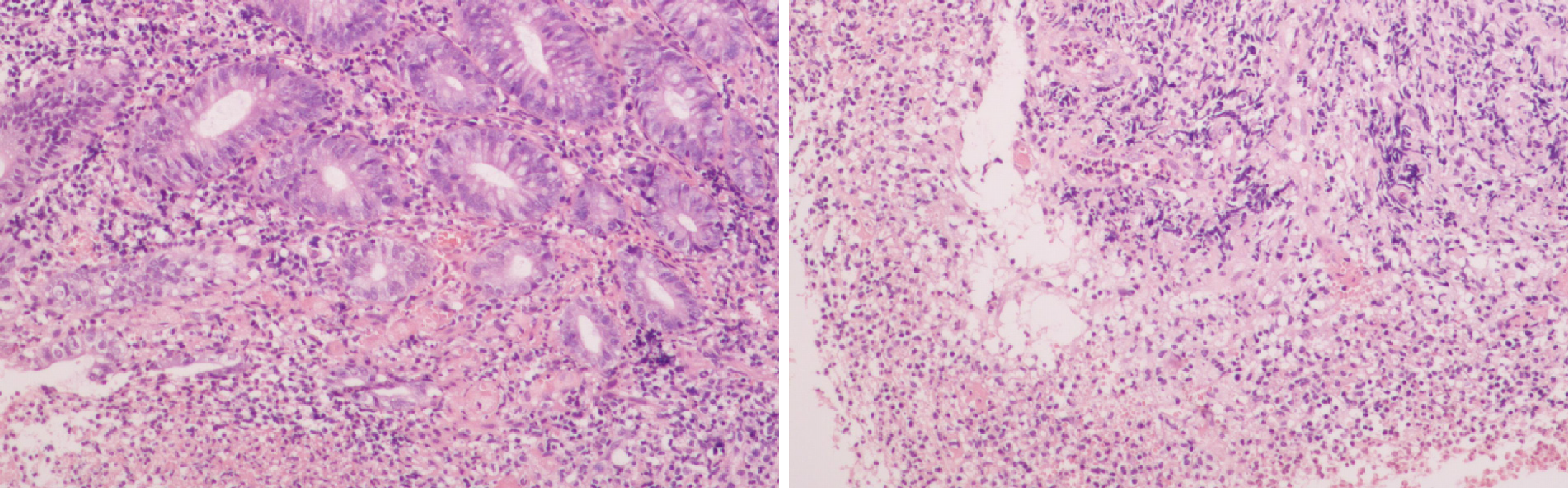

Endorectal ultrasonography showed a hypoechoic area under the mucosa located 5 cm laterally from the 8-12 o’clock position of the anal margin in the anal canal. The mass was diagnosed as a submucosal infection. Enteroscopy showed hyperplasia and adhesions on the rectal mucosa at the margin of the perianal incision, which was diagnosed as proctitis. Biopsy samples were taken during endoscopy (Figure 1). Pathological examination revealed moderate to severe acute and chronic mucositis, inflammatory necrosis, and granulation tissue hyperplasia (Figure 2).

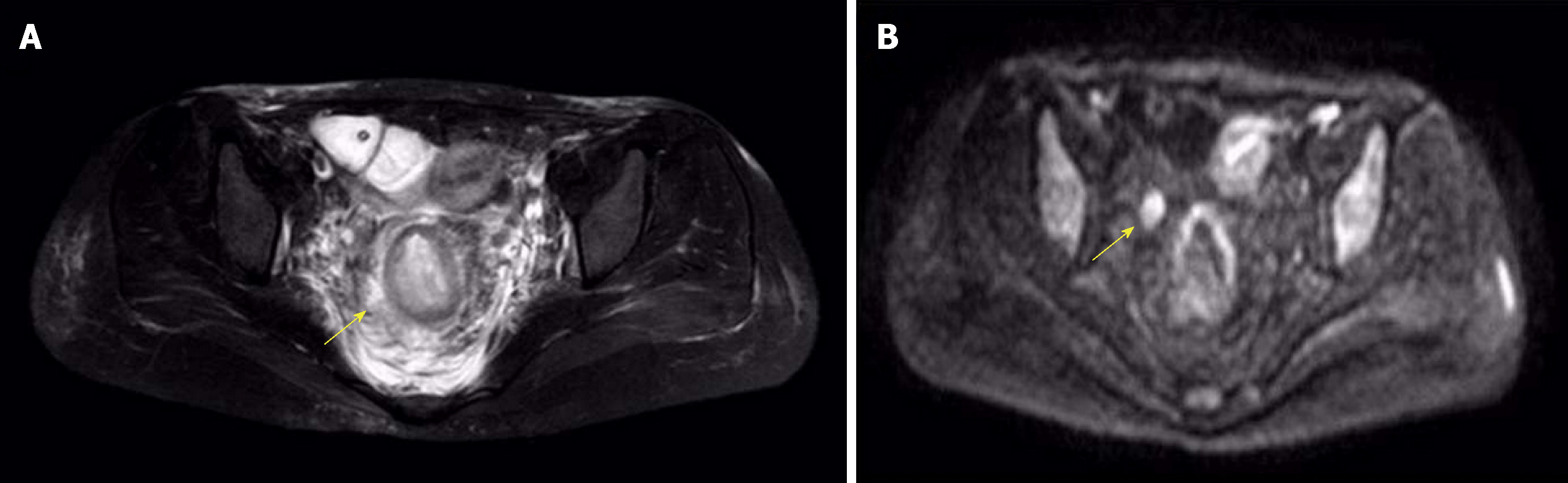

On days 3, 10, 16, and 23 of hospitalization, the patient underwent several anal exploration and hemostasis surgeries due to recurrent anal hemorrhage. The source of bleeding remained unidentified. Twenty-two days later, the patient was transferred to a secondary reference hospital for a laparoscopic assisted pelvic exploration and ileostomy. Excessive purulent secretions and necrotic tissue around the anus were observed in colonoscopy. In magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), thickening and edema of the rectum and external genital organs were observed along with multiple exudations and small lymph nodes around the rectum (Figure 3). After the surgery, continuous irrigations and drainage via an anal double cannula was performed. The patient was still feverish and suffered from very extensive, bloody discharge from the anus resulting in hypovolemic shock. Sigmoid colostomy with rectal and anal resection was suggested, but the patient did not consent to surgery and so after symptomatic treatment, she was discharged on request.

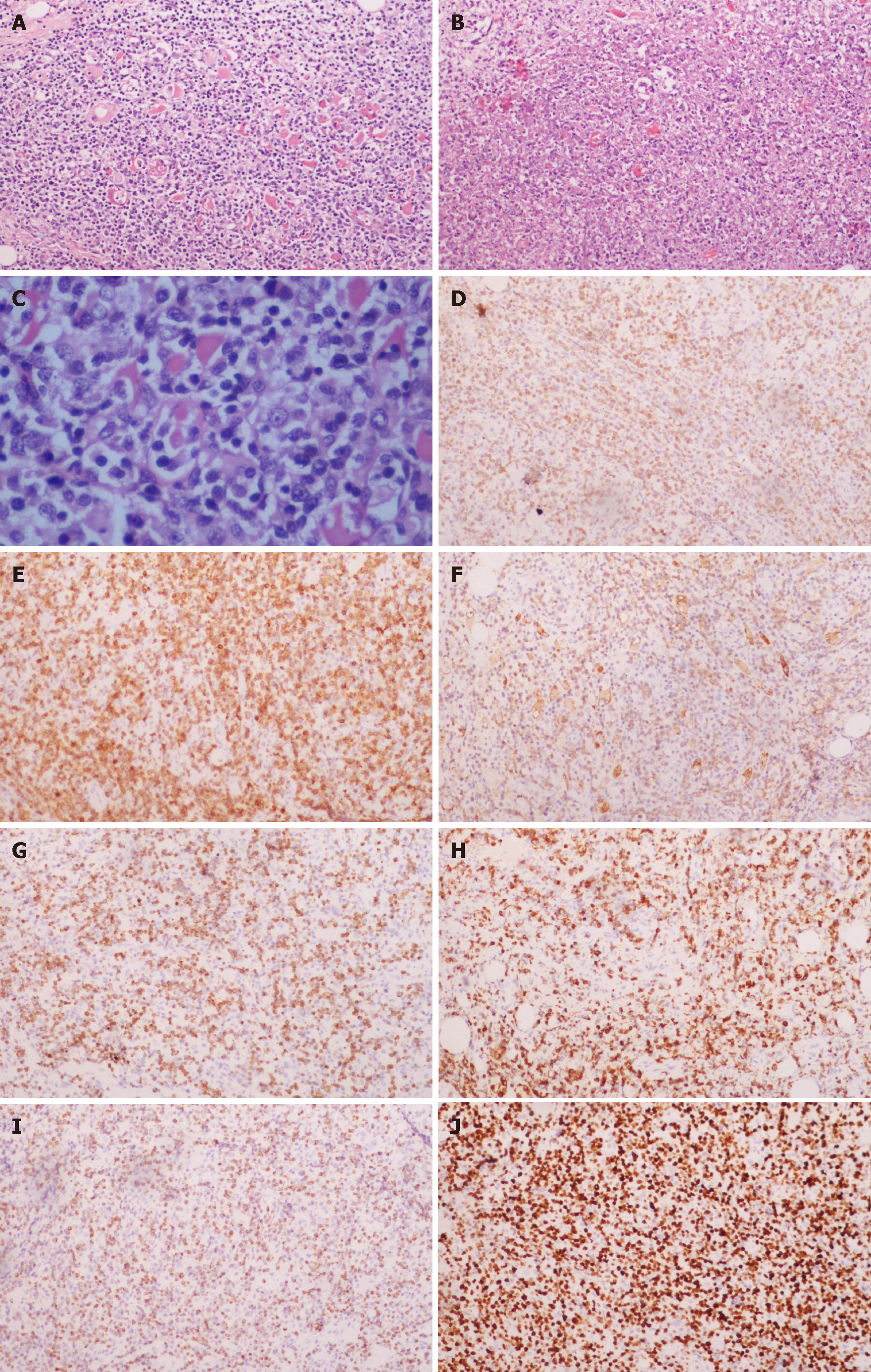

For the next 4 mo, the patient was treated conservatively in an outpatient clinic, however, the symptoms returned and the patient was readmitted to hospital. In addition to the perianal abscess, rectal vaginal fistula and inflammation of perianal tissue were diagnosed. On the seventh day of admission, the anorectal abscess was resected and the pelvic abscess was drained. A biopsy of the left inguinal lymph nodes was performed. Histopathological and immunohistochemical examinations showed the presence of CK (-), LCA (+), CD2 (+), CD3 (+), CD4 (-), CD5(-), CD8 (partial), CD56 (+), CD10 (-), CD20 (-), CD30 (partial), CD15 (-), CD79a (-), CD138 (-), CylinD1 (-), TIA (-), EMA (-), CD7 (-), granzyme B (+), perforin (+), and CD57 (-) cells that suggested a diagnosis of ENKTL (Figure 4). The Ki67 index was 65%.

Two weeks later, before the histopathological results were available, the patient was transferred to a tertiary reference hospital. The results of lymphocyte immunoassay are shown in Table 1.

| % | |

| CD3 | 91.7 |

| CD3+CD4+ | 49.8 |

| CD3+CD8+ | 39.6 |

| CD3+CD4+/CD3+CD8+ | 1.26 |

| B cells | 1.4 |

| NK cells | 5.1 |

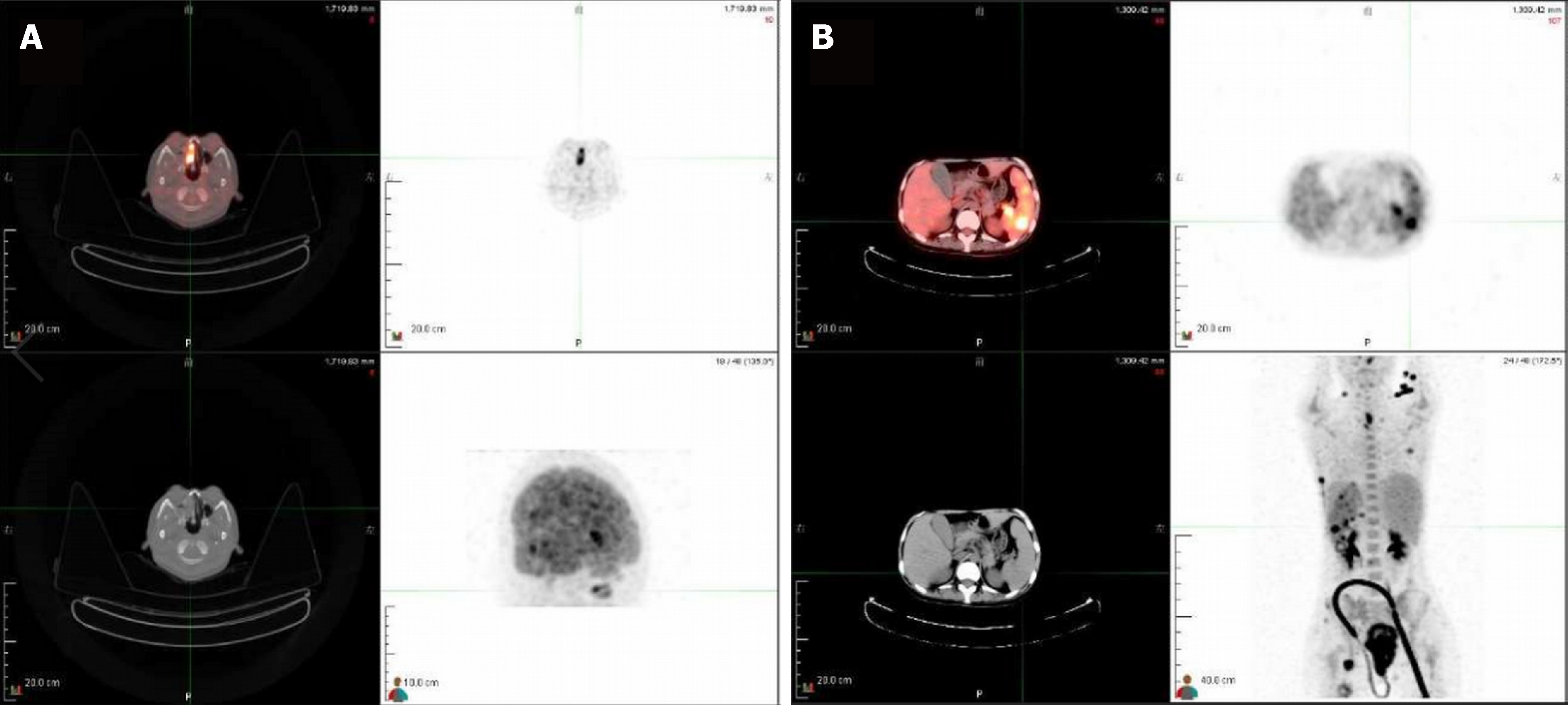

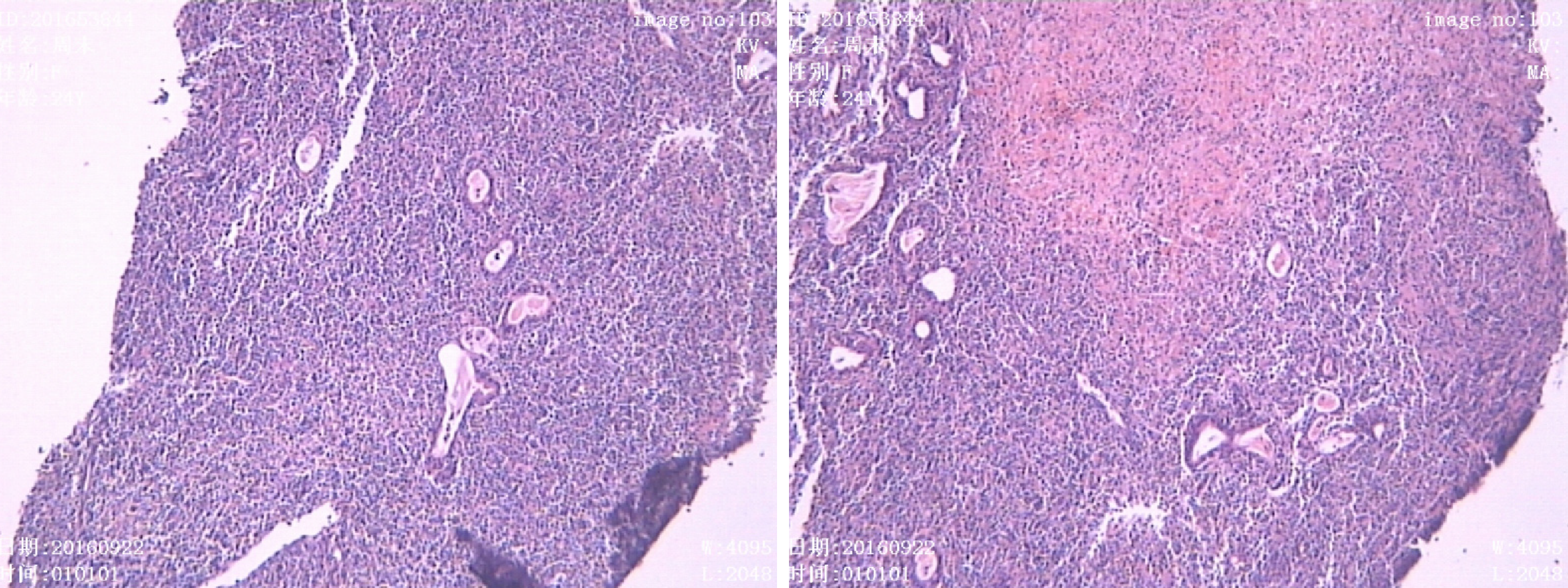

A PET-CT scan performed after the transfer showed a thickened rectal wall, pathological mass in the perianal area with multiple exudations and gas in the peripheral fat space, enlarged spleen, pathological mass in the right nasal cavity, and thickened posterior wall of the trachea. In the scan range, the skin was irregularly thickened and high-density, subcutaneous shadows were visible (left neck, chest, abdomen, and left hip). Generalized lymphadenopathy (bilateral axillary, abdominal, pelvic cavity, and left inguinal) was observed, in line with the diagnosis of lymphoma. In addition, signs of sinusitis and nodular foci of increased metabolism in left margin of L3 vertebral body and left iliac crest were visible (Figure 5). The images of nasopharyngeal biopsy were typical for ENKTL (Figure 6). Immunohistochemistry showed CD20 (-), CD3 (+), CD2 (+), CD56 (+), and TIA (+) cells with a Ki67 index of 90%. Fluorescent in situ hybridization showed the presence of EBV-encoded small RNAs (EBERs). A final diagnosis of stage IV ENKTL was made.

Two weeks after the admission, COP chemotherapy was initiated (cyclophosphamide 1.3 g on day 1, vincristine 4 mg on day 1, and prednisone 50 mg b.i.d on days 1-5). However, on day 1, a massive anal hemorrhage resulting in hypovolemic shock occurred. As a result, chemotherapy was stopped and shock management including intravascular fluid therapy and blood transfusions were implemented. The patient’s condition continued to deteriorate despite the treatment.

Three weeks later, the patient was transferred to Jiangbei People's Hospital for conservative maintenance therapy. Three days after the admission, continuous blood oozing from the anus was noted. Intravenous administration of a hemostatic agent (etamsylate and P-aminomethylbenzoic acid) was ineffective in stopping the bleeding. Coagulation panel showed activated partial thromboplastin time 58.40 s (reference value 20-40 s), fibrinogen 1.62 g/L (reference value 2-4 g/L), and D-dimer 2.94 µg/mL (reference value < 0.2 µg/mL). Because of suspected coagulopathy, daily infusions of red blood cells, cryoprecipitate, platelets, and plasma were introduced. Despite shock management, the patient's condition gradually deteriorated and she died 9 mo after presentation.

What could raise suspicion of ENKTL in a patient with typical symptoms of a common perianal abscess? The complicated postoperative course of the disease, including persistent fever and recurrent, massive anal hemorrhage resulting in hypovolemic shock not relieved after re-operation and antibiotic treatment, is not a typical course of perianal abscess and should prompt further diagnostic procedures[19]. However, as nasopharyngeal symptoms were not evident at the first admission and no abnormalities in imaging and routine laboratory analysis suggested a suspicion of systemic disease, malignancy was not included in the differential diagnosis at an early stage.

Pathological and immunohistochemical examinations of colonoscopy biopsies showed local inflammatory necrosis and inflammatory granulation tissue hyperplasia. This misleading result might be caused by the fact that routine colonoscopic biopsies are superficial and do not reach submucosal tissues potentially containing lymphoma cells. Therefore, one could not suggest changing the primary diagnosis. In such cases, a deep tissue biopsy may improve the accuracy of the diagnosis.

In the anal canal, lymphoid tissue is accumulated around the anus where lymphoma cells may block the internal glands of the anus and cause perianal abscess formation. Therefore, in the cases of perianal disease with unexplained blood in the stool, fever, anemia, weight loss, and other systemic symptoms, timely biopsy may facilitate accurate diagnosis and allow initiation of adequate treatment[20,21]. In addition, full-body imaging can further reduce the risk of misdiagnosis.

Lymphoma cases presenting with a perianal abscess are very rare. Ninety percent of the anorectal abscesses are caused by acute infection of the anal glands. In the remaining cases, the abscess is formed as a result of other diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, tuberculosis, or tumors. Gastrointestinal lymphoma is usually secondary to a wide range of lymph node diseases, and primary gas-trointestinal lymphoma is relatively rare[22-24]. There are a few reports on lymphomas in the anorectal area, including ENKTL originating from the rectum. Kakimoto et al[25] reported a case of refractory ulcerative colitis presenting with colonic submucosal tumors histopathologically diagnosed as ENKTL. Valbuena et al[26] reported a case of a male who underwent rectal resection for clinical suspicion of carcinoma. After histopathologic examination, it was diagnosed as classical Hodgkin lymphoma (nodular sclerosis type) involving the rectum.

We present a rare case of fatal, disseminated ENKTL with rectal involvement in which a perianal abscess was initially suggested. Non-specific symptoms and results of imaging, laboratory analysis, and colonoscopic biopsy did not suggest systemic disease and consequently the final diagnosis was delayed. Therefore, a complicated course of surgical treatment, recurrent hemorrhages, and rapid deterioration of patient’s condition should prompt further investigation, and systemic and neoplastic diseases should be included in the differential diagnosis of any potentially benign perianal abscess.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Lazăr DC, Williams R S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, Harris NL, Stein H, Siebert R, Advani R, Ghielmini M, Salles GA, Zelenetz AD, Jaffe ES. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127:2375-2390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4245] [Cited by in RCA: 5424] [Article Influence: 602.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Li YX, Fang H, Liu QF, Lu J, Qi SN, Wang H, Jin J, Wang WH, Liu YP, Song YW, Wang SL, Liu XF, Feng XL, Yu ZH. Clinical features and treatment outcome of nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma of Waldeyer ring. Blood. 2008;112:3057-3064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dobashi A, Tsuyama N, Asaka R, Togashi Y, Ueda K, Sakata S, Baba S, Sakamoto K, Hatake K, Takeuchi K. Frequent BCOR aberrations in extranodal NK/T-Cell lymphoma, nasal type. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2016;55:460-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sandell RF, Boddicker RL, Feldman AL. Genetic Landscape and Classification of Peripheral T Cell Lymphomas. Curr Oncol Rep. 2017;19:28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tse E, Kwong YL. Diagnosis and management of extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma nasal type. Expert Rev Hematol. 2016;9:861-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Au WY, Weisenburger DD, Intragumtornchai T, Nakamura S, Kim WS, Sng I, Vose J, Armitage JO, Liang R; International Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma Project. Clinical differences between nasal and extranasal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma: a study of 136 cases from the International Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma Project. Blood. 2009;113:3931-3937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 507] [Cited by in RCA: 607] [Article Influence: 35.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Suzuki R. Pathogenesis and treatment of extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma. Semin Hematol. 2014;51:42-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Horwitz SM, Ansell SM, Ai WZ, Barnes J, Barta SK, Choi M, Clemens MW, Dogan A, Greer JP, Halwani A, Haverkos BM, Hoppe RT, Jacobsen E, Jagadeesh D, Kim YH, Lunning MA, Mehta A, Mehta-Shah N, Oki Y, Olsen EA, Pro B, Rajguru SA, Shanbhag S, Shustov A, Sokol L, Torka P, Wilcox R, William B, Zain J, Dwyer MA, Sundar H. NCCN Guidelines Insights: T-Cell Lymphomas, Version 2.2018. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16:123-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Li CC, Tien HF, Tang JL, Yao M, Chen YC, Su IJ, Hsu SM, Hong RL. Treatment outcome and pattern of failure in 77 patients with sinonasal natural killer/T-cell or T-cell lymphoma. Cancer. 2004;100:366-375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Huang YH, Huang CT, Tan SY, Chuang SS. Primary gastric extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type, with acquisition of CD20 expression in the subcutaneous relapse: report of a case with literature review. J Clin Pathol. 2015;68:943-945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yahalom J, Illidge T, Specht L, Hoppe RT, Li YX, Tsang R, Wirth A; International Lymphoma Radiation Oncology Group. Modern radiation therapy for extranodal lymphomas: field and dose guidelines from the International Lymphoma Radiation Oncology Group. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;92:11-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 284] [Article Influence: 28.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Schorb E, Finke J, Ferreri AJ, Ihorst G, Mikesch K, Kasenda B, Fritsch K, Fricker H, Burger E, Grishina O, Valk E, Zucca E, Illerhaus G. High-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplant compared with conventional chemotherapy for consolidation in newly diagnosed primary CNS lymphoma--a randomized phase III trial (MATRix). BMC Cancer. 2016;16:282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kim SJ, Park S, Kang ES, Choi JY, Lim DH, Ko YH, Kim WS. Induction treatment with SMILE and consolidation with autologous stem cell transplantation for newly diagnosed stage IV extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma patients. Ann Hematol. 2015;94:71-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Takata K, Hong ME, Sitthinamsuwan P, Loong F, Tan SY, Liau JY, Hsieh PP, Ng SB, Yang SF, Pongpruttipan T, Sukpanichnant S, Kwong YL, Hyeh Ko Y, Cho YT, Chng WJ, Matsushita T, Yoshino T, Chuang SS. Primary cutaneous NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type and CD56-positive peripheral T-cell lymphoma: a cellular lineage and clinicopathologic study of 60 patients from Asia. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39:1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Au WY, Ma SY, Chim CS, Choy C, Loong F, Lie AK, Lam CC, Leung AY, Tse E, Yau CC, Liang R, Kwong YL. Clinicopathologic features and treatment outcome of mature T-cell and natural killer-cell lymphomas diagnosed according to the World Health Organization classification scheme: a single center experience of 10 years. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:206-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 241] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Vazquez A, Khan MN, Blake DM, Sanghvi S, Baredes S, Eloy JA. Extranodal natural killer/T-Cell lymphoma: A population-based comparison of sinonasal and extranasal disease. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:888-895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kirsch BJ, Chang SJ, Le A. Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Metabolism. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018;1063:95-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gill H, Liang RH, Tse E. Extranodal natural-killer/t-cell lymphoma, nasal type. Adv Hematol. 2010;2010:627401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wright WF. Infectious Diseases Perspective of Anorectal Abscess and Fistula-in-ano Disease. Am J Med Sci. 2016;351:427-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Nelson RL, Prasad ML, Abcarian H. Anal carcinoma presenting as a perirectal abscess or fistula. Arch Surg. 1985;120:632-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Marti L, Nussbaumer P, Breitbach T, Hollinger A. [Perianal mucinous adenocarcinoma. A further reason for histological study of anal fistula or anorectal abscess]. Chirurg. 2001;72:573-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Primary gastrointestinal lymphomas. Lancet. 1977;1:1191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Inghirami G, Chan WC, Pileri S; AIRC 5xMille consortium ‘Genetics-driven targeted management of lymphoid malignancies’. Peripheral T-cell and NK cell lymphoproliferative disorders: cell of origin, clinical and pathological implications. Immunol Rev. 2015;263:124-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Miyake MM, Oliveira MV, Miyake MM, Garcia JO, Granato L. Clinical and otorhinolaryngological aspects of extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma, nasal type. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;80:325-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kakimoto K, Inoue T, Nishikawa T, Ishida K, Kawakami K, Kuramoto T, Abe Y, Morita E, Murano N, Toshina K, Murano M, Umegaki E, Egashira Y, Okuda J, Tanigawa N, Hirata I, Katsu K, Higuchi K. Primary CD56+ NK/T-cell lymphoma of the rectum accompanied with refractory ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:576-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Valbuena JR, Gualco G, Espejo-Plascencia I, Medeiros LJ. Classical Hodgkin lymphoma arising in the rectum. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2005;9:38-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |