Published online Nov 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i21.3524

Peer-review started: April 8, 2019

First decision: August 1, 2019

Revised: August 26, 2019

Accepted: September 9, 2019

Article in press: September 9, 2019

Published online: November 6, 2019

Processing time: 216 Days and 10.9 Hours

The perivascular epithelioid cell tumour (PEComa) family of tumours mainly includes renal and hepatic angiomyolipomas, pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis and clear cell “sugar” tumour of the lung. Several uncommon tumours with similar morphological and immunophenotypical characteristics arising at a variety of sites (abdominal cavity, digestive tract, retroperitoneum, skin, soft tissue and bones) are also included in the PEComa family and are referred to as PEComas not otherwise specified.

We present a 37-year-old female patient who underwent resection of an 8.5 cm × 8 cm × 4 cm retroperitoneal tumour, which eventually was diagnosed as PEComa of uncertain biological behaviour. Three years after the operation, the patient remains without any evidence of recurrence. A search was performed in the Medline and EMBASE databases for articles published between 1996 and 2018, and we identified 31 articles related to retroperitoneal and perinephric PEComas. We focused on sex, age, maximum dimension, histological and immunohistochemical characteristics of the tumour, follow-up and long-term outcome. Thirty-four retroperitoneal (including the present one) and ten perinephric PEComas were identified, carrying a malignant potential rate of 44% and 60%, respectively. Nearly half of the potentially malignant PEComas presented with or developed metastases during the course of the disease.

Retroperitoneal PEComas are not as indolent as they are supposed to be. Radical surgical resection constitutes the treatment of choice for localized disease, while mammalian target of the rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors constitute the most promising therapy for disseminated disease. The role of mTOR inhibitors as adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapies needs to be evaluated in the future.

Core tip: The retroperitoneal space represents the third most frequent location for perivascular epithelioid cell tumours (PEComas) not otherwise specified development. Half were stratified as potentially malignant, and nearly half of the potentially malignant tumours presented with or developed metastases during the course of the disease. Thus, retroperitoneal PEComas are not as indolent as they are supposed to be. Radical surgical resection constitutes the treatment of choice for localized disease, while mammalian target of the rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors constitute the most promising therapy for disseminated disease. The role of mTOR inhibitors as adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapies needs to be evaluated in the future.

- Citation: Touloumis Z, Giannakou N, Sioros C, Trigka A, Cheilakea M, Dimitriou N, Griniatsos J. Retroperitoneal perivascular epithelioid cell tumours: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(21): 3524-3534

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i21/3524.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i21.3524

Perivascular epithelioid cell tumour (PEComa) was first included in the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumours as a distinctive entity in 2002, defined as “a mesenchymal tumour composed of histologically and immunohistochemically distinctive perivascular epithelioid cells”[1]. PEComa family tumours mainly included renal and hepatic angiomyolipomas (AMLs), lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM), lymphangiomyoma and clear cell “sugar” tumour (CCST) of the lung. In 2004, the WHO classification of tumours subdivided AML further into classic AML and epithelioid AML, defining epithelioid AML as “a potentially malignant mesenchymal neoplasm, characterized by a proliferation of predominantly epithelioid cells”[2].

Currently, PEComas are considered a group of ubiquitous neoplasms sharing morphological, immunohistochemical, ultrastructural and genetic distinctive features[3], which typically express smooth muscle and melanocytic[4] as well as lymphatic vascular[5] markers. Several uncommon tumours with similar morphological and immunophenotypical characteristics arising at a variety of sites (abdominal cavity, digestive tract, retroperitoneum, skin, soft tissue and bones)[6] are also included in the PEComa family and are referred to as PEComas not otherwise specified (PEComas NOS)[7]. However, some authors[8,9] argue that the terminology used for non-pulmonary PEComas is confusing.

Although reviews for renal epithelioid AMLs, extrarenal AMLs, gastrointestinal PEComas and gynaecological PEComas have been published, a thorough review of retroperitoneal PEComas is missing. Regarding a case of retroperitoneal tumour resection that was postoperatively diagnosed as PEComa, we conducted a review of all published reports on retroperitoneal and perinephric PEComas, evaluating their biological behaviour in both sites, as well as possible differences between them.

A 37-year-old Caucasian female patient was investigated for persistently abnormal alkaline phosphatase (ALP) plasma values.

Although the patient remained asymptomatic, repeated liver function tests over a 9-mo period revealed persistently increased ALP plasma values.

The patient had a nonsignificant past medical history, no history of recent illness and/or trauma and was not receiving any medication at the time of referral.

The patient was a nonsmoker and had no personal or family history of other diseases.

The clinical examination was unremarkable.

All haematological and biochemical laboratory results were reported within normal limits except elevated ALP (> 500 IU/L). Tumour markers were reported as within normal limits.

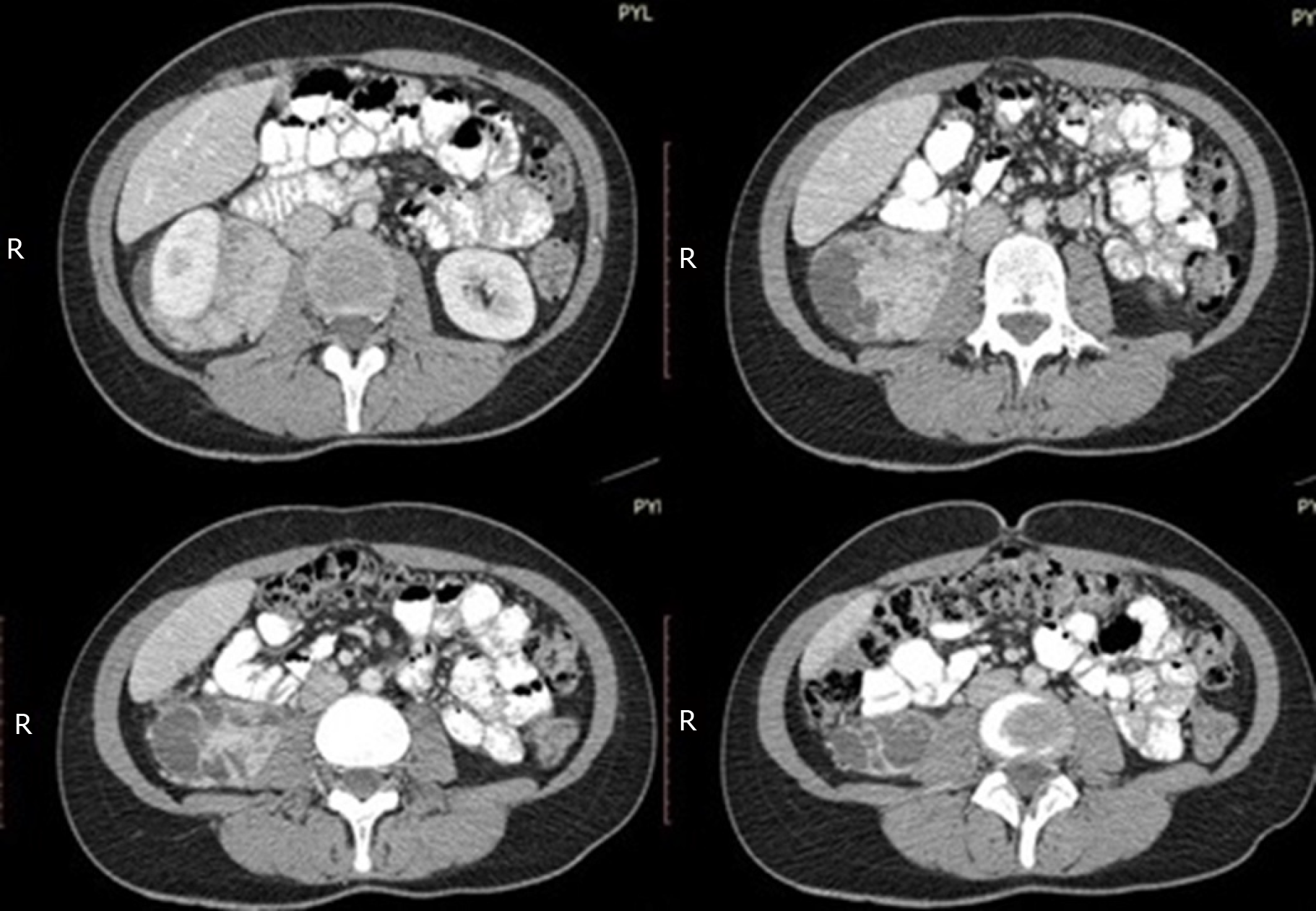

A liver ultrasound scan revealed gallbladder sludge and multiple focal lesions in the hepatic parenchyma. An abdominal computer tomography (CT) scan disclosed multiple focal lesions of the liver enhancing during the arterial phase and as an incidental finding an 8.5 cm × 8 cm × 4 cm solid and heterogeneous retroperitoneal mass anterior to the right psoas muscle and posterior and inferior to the right kidney, which encapsulated the right ureter in its whole length and inferiorly to the level of the right lobe of the liver, abutting the right kidney anteriorly and laterally (Figure 1).

A pig-tail catheter was first placed in the right ureter, after which the patient underwent exploratory laparotomy through a midline incision under general endotracheal anaesthesia. Cholecystectomy and excision of the retroperitoneal mass were performed, while multiple Tru-cut biopsies from the liver lesions were taken. Her postoperative course was uneventful, and she was discharged on the 5th postoperative day.

The gallbladder’s sludge was considered the aetiology for the abnormal ALP, while the malignant nature of the retroperitoneal tumour could not be excluded based on imaging findings.

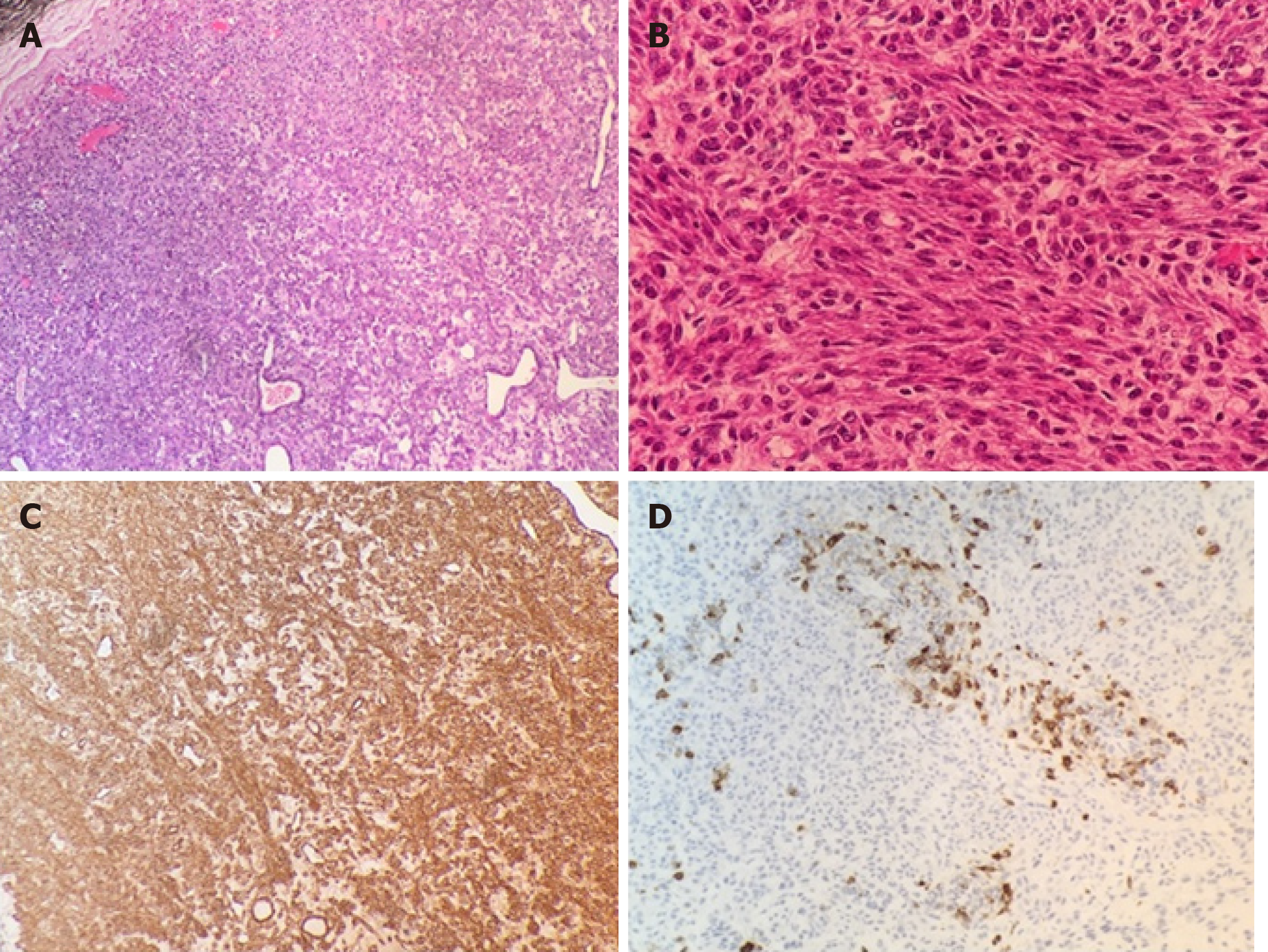

Pathological examination with haematoxylin and eosin staining of the retroperitoneal mass revealed a completely resected encapsulated tumour composed of polygonal or spindle cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm and mildly atypical nuclei arranged in bundles around compressed, thin-walled vascular channels. Less than 1 mitosis per 10 high-power field (HPF) was present, while necrosis was absent. The immunohistochemical staining results were as follows: Desmin (+ diffuse), SMA (+ diffuse), HMB-45 (+ focal), PgR (+ diffuse), melan-A (-), CD34 (-), CD117 (-), S-100 (-), ER (-), Ki67 < 2%. The tumour was classified as “retroperitoneal PEComa of uncertain biological behaviour” (Figure 2).

Histological examination of the gallbladder disclosed “chronic cholecystitis”, while the biopsies from the liver were diagnostic of “focal nodular hyperplasia”.

After three years from the initial operation, the patient remains asymptomatic without any evidence of local or distant recurrence.

The Medline and EMBASE databases were searched using as key words the terms “perivascular epithelioid cell tumour(s)”, “PEComa(s)”, “retroperitoneal PEComa(s)”, “perinephric PEComa(s)”, “extrarenal PEComa(s)”, “non-pulmonary PEComa(s)” and “PEComa NOS” in several combinations.

For assessment of the published reports, we used the following terminology: (1) Renal classic AML, for AMLs confined to the kidney; (2) Renal epithelioid AML, for AMLs with epithelioid variant confined to the kidney; (3) Extrarenal AML, for AMLs developed at any extrarenal site; (4) Retroperitoneal AMLs, for pure retroperitoneal AMLs completely separately from the kidney(s); (5) Gastrointestinal PEComas, for tumours developed in the abdominal cavity or the digestive tract; (6) Gynaecological PEComas; (7) Perinephric PEComas, for tumours developed between Gerota’s and Zuckerkanld’s fascia[10]; and (8) Retroperitoneal PEComas, for retroperitoneal tumours completely separately from the kidney(s) and with a histology report other than AML.

We included articles between 1996 and 2018; the final search was conducted in December 2018. All articles with at least an abstract in the English language were considered eligible for inclusion. Thirty articles were identified, and the following parameters were studied: Sex, age, maximum dimension of the tumour, histological and immunohistochemical characteristics of the tumour, follow-up and long-term outcome.

AMLs constitute the most common, well-described and well-studied member of the PEComa family of tumours. On the other hand, non-renal AMLs/non-pulmonary PEComas are seldom reported. Approximately 120 renal epithelioid AMLs[11], fewer than 100 extrarenal AMLs[8,9], 50 gastrointestinal PEComas[12] and 78 gynaecological PEComas[13] have been reported so far in the English literature. In the present review, 33 (34 including the present case) retroperitoneal and 10 perinephric PEComas cases were identified[4,14-43], making retroperitoneal space the third most frequent location for PEComas NOS development (Table 1).

| Author | Ref. | Year | Localization | No. patients | Sex/age | Maximum diameter (cm) | Biological behavior stratification based on Folpe et al[44] criteria | Follow-up (mo) | Long-term outcome |

| Audard | [14] | 2004 | Retroperito-neal | 1 | M/45 | 21 | Malignant | NA | NA |

| Gunia | [15] | 2005 | Perinephric | 1 | F/57 | 5.3 | Uncertain | 8 | No recurrence |

| Shin | [16] | 2008 | Retroperito-neal | 1 | F/47 | 19 | Malignant | NA | NA |

| Hornick | [17] | 2008 | Retroperito-neal | 10 | F/43 | 9 | 10 sclerosing PEComas | NA | NA |

| F/46 | 4.5 | 64 | No recurrence | ||||||

| F/50 | 11.5 | 6 Uncertain | 51 | No recurrence | |||||

| F/51 | 22 | 2 Malignant | 22 | No recurrence | |||||

| F/59 | NA | 2 NA | 39 | No recurrence | |||||

| F/53 | 4.5 | 15 | NA | ||||||

| F/73 | 9 | 23 | No recurrence | ||||||

| F/47 | 28 | 10 | No recurrence | ||||||

| F/49 | 6.1 | NA | NA | ||||||

| F/48 | 19 | NA | NA | ||||||

| Lans | [18] | 2009 | Retroperito-neal | 1 | F/28 | 15 | Malignant | 5 | No recurrence |

| Koening | [19] | 2009 | Retroperito-neal | 1 | F/27 | 10 | Malignant | NA | NA |

| Subbiah | [20] | 2010 | Retroperito-neal | 1 | F/58 | 17 | NA | 48 | Liver and lung metastases |

| Wagner | [21] | 2010 | Retroperito-neal | 1 | M/65 | 20 | NA | 36 | Multifocal retroperitoneal recurrence |

| Suemitsu | [22] | 2010 | Retroperito-neal | 1 | M/39 | Confirmation of malignancy retros-pectively | 216 | Lung metastases | |

| deLeon | [23] | 2010 | Retroperito-neal | 1 | F/76 | 15 | Malignant | 48 | Brain, T-spine, sacrum metastases |

| Retroperito-neal | 1 | F/38 | 7 | Malignant | 70 | Progressive disease | |||

| Kumar | [24] | 2010 | Perinephric | 1 | F/54 | 8 | Malignant (=gross infiltration of IVC) | NA | NA |

| Valiathan | [25] | 2011 | Perinephric | 1 | F/50 | 8 | Sclerosing PEComa | NA | NA |

| Uncertain | |||||||||

| Alguraan | [26] | 2012 | Perinephric | 1 | F/43 | 12.8 | Malignant | NA | NA |

| Santi | [27] | 2012 | Retroperito-neal | 1 | F/66 | 8.5 | Sclerosing PEComa | 24 | No recurrence |

| Uncertain | |||||||||

| Rekhi | [28] | 2012 | Retroperito-neal | 1 | F/56 | 5 | Sclerosing PEComa | NA | NA |

| Uncertain | |||||||||

| Yang | [29] | 2012 | Perinephric | 1 | F/21 | 2.5 | Malignant | 3 | No recurrence |

| Theodosopoulos | [30] | 2012 | Retroperito-neal | 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Wu | [31] | 2013 | Retroperito-neal | 1 | F/55 | 7.5 | Malignant | 7 | Liver metastases |

| Guglielmetti | [32] | 2013 | Retroperito-neal | 1 | M/42 | 2.5 | Benign | 38 | No recurrence |

| Dickson | [4] | 2013 | Retroperito-neal | 2 | F/24 | 25 | Malignant | 22 | Complete response |

| F/40 | 16 | Complete response | |||||||

| Perinephric | 1 | M/65 | 36 | Death due to metastatic disease | |||||

| Pata | [33] | 2014 | Retroperito-neal | 1 | F/66 | 12 | Uncertain | 12 | No recurrence |

| Wildgruber | [34] | 2014 | Retroperito-neal | 1 | M/75 | 15 | Benign | NA | NA |

| Oh | [35] | 2014 | Retroperito-neal | 1 | F/68 | 9 | Malignant | NA | Liver and Bone metastases |

| Morosi | [36] | 2014 | Retroperito-neal | 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Nakanishi | [37] | 2014 | Perinephric | 1 | F/51 | 20 | Malignant | 5 | Death due to disease progression |

| Liang | [38] | 2015 | Retroperito-neal | 1 | F/51 | 20 | Malignant | 7 | No recurrence |

| Bhanushali | [39] | 2015 | Perinephric | 1 | F/55 | 7 | Uncertain | NA | NA |

| To | [40] | 2015 | Retroperito-neal | 1 | F/52 | 8.5 | Sclerosing PEComa | 23 | No recurrence |

| NA | |||||||||

| Danilewicz | [41] | 2017 | Perinephric | 1 | F/66 | 1.5 | Malignant | NA | NA |

| Cihan | [42] | 2018 | Perinephric | 1 | F/42 | 9 | Benign | 24 | Intra-abdominal metastases |

| Singer | [43] | 2018 | Retroperito-neal | 1 | F/70 | 33 | Malignant | 1 | No recurrence |

| Present Case | Retroperito-neal | 1 | F/37 | 8.5 | Uncertain | 38 | No recurrence | ||

| 10 34 |

PEComas are considered neoplasms of unknown origin. According to a hypothesis, PEComas derive from undifferentiated cells of the neural crest, since they express several melanocytic markers[3]. Another hypothesis proposed that they have a smooth muscle origin with possible molecular alterations, leading to the expression of melanocytic markers[44]. A third hypothesis supported that the expression of melanocytic markers is acquired and related to chromosomal translocations or mutations affecting the pathway of melanosomal protein expression during tumour development[45]. The most recent theory, however, addressed that both PEComas and gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs) have a common origin from telocytes, since markers expressed in telocytes (e.g., S-100, SMA, VEGF) are also expressed in PEComas[46].

AML and LAM have been proposed to be strongly associated with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), an inherent autosomal dominant syndrome resulting from heterozygous mutations of either the TSC1 or TSC2 tumour suppressor gene, causing a multisystem development of benign tumours[47]. Although renal AMLs develop in > 50% of TSC patients[47], less than 20% of AML patients have underlying TSC[48]. Thus, most AML cases arise sporadically, a fact probably related to new mutations[45], inactivating mutations, or difficulties in detection of mutations by conventional methods in either gene or due to the presence of additional still unidentified causative (TSC) loci[49]. In three reports of the present study[4,21,33], cytogenetic analysis was performed, but only one[4] concluded a loss of heterozygosity in the TSC2 gene.

PEComas are composed of nests and sheets of mainly epithelioid and occasionally spindled cells with clear to granular eosinophilic cytoplasm. The proportions of the two parts may vary significantly. Epithelioid cells are located immediately perivascular, while spindle cells are located away from the vessel’s wall. Usually, PEC surrounds the blood vessels, arranging radially around the lumen, forming bunch- and web-shaped structures, while in a minority of cases, it has a focal association with the blood vessel walls. In all cases, PEC replaces the normal smooth muscle and collagen in the muscular wall of the vessel[17,38,41]. A sclerosing variant of PEComa with predominant sclerotic and hyalinized stroma has also been reported[17,25,27,28,40].

A diagnosis of PEComa is usually established postoperatively by histology. Based on the CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings, however, an accurate preoperative diagnostic rate does not exceed 31% and 40%, respectively, for AMLs and is 0% for any other histological subtype[50]. In particular, retroperitoneal PEComas are usually diagnosed preoperatively as well-differentiated liposarcomas[36].

The diagnosis is based on immunohistochemistry. Co-expression of melanocytic markers such as melan-A and/or HMB-45 (expressed in epithelioid cells) and smooth muscle markers such as smooth muscle actin, pan-muscle actin, muscle myosin, and calponin (expressed in spindle cells) is considered diagnostic[14-43].

The biologic behaviour of PEComas remains unclear. Folpe et al[51] proposed the following: (1) Tumour size > 5 cm; (2) Mitotic rate > 1/50 HPF; (3) High nuclear grade and cellularity; (4) Presence of necrosis; (5) Vascular invasion; and (6) An infiltrative growth pattern, as risk factors for malignancy, stratifying the biological behaviour of PEComas as (1) being benign (tumours < 5 cm with one risk feature), (2) having uncertain malignant potential (tumours > 5 cm with no other risk features), and (3) being malignant (tumours with two or more risk features). Although Folpe’s criteria have been criticized[7], they continue to have utility, especially in helping to categorize lesions with low malignant potential. Applying Folpe’s criteria, the present study revealed that among the 34 retroperitoneal PEComas, 15 were malignant (44%), 10 (29%) exhibited uncertain biological behaviour, and 2 (6%) exhibited benign behaviour, while in 7 cases, the status was not stated. Among the 10 perinephric tumours, 6 were malignant (60%), 3 (30%) exhibited uncertain biological behaviour and 1 (10%) exhibited benign behaviour. There are clearly no differences in the malignant potential between the published retroperitoneal and perinephric PEComas. The literature addresses that the biological behaviour of the non-pulmonary PEComa family tumours varies widely. Renal classic AML constitutes an otherwise benign lesion, although rare cases of sarcomatous transformation have been described[52]. Renal epithelioid AML resembles the biological behaviour of renal cell carcinoma with a 17% recurrence rate, 49% metastatic rate and 33% death rate[53,54]. Extrarenal AML only occasionally develops malignant biological behaviour[8]; 52% of gastrointestinal[12] and 50% of gynaecological PEComas[55] have malignant potential, while sclerosing PEComa pursues an indolent course, unless associated with a frankly histologically malignant component[17].

The present study adds to our knowledge that 45% of retroperitoneal and 60% of perinephric PEComas have malignant potential. Moreover, 7 out of 15 (47%) potentially malignant retroperitoneal PEComas presented with or developed metastases in the course of the disease, while 2 out of the 6 (33%) potentially malignant perinephric PEComas developed metastases. Based on the above, we postulate that retroperitoneal PEComas are not as indolent as they are supposed to be, since 20%-21% of all reported cases presented with or developed metastases in the course of the disease. The above findings should be taken into consideration in designing therapeutic strategies and surveillance.

Since retroperitoneal PEComas cannot easily be differentiated from sarcomas and because half of them may develop a potentially malignant biological behaviour, radical surgical resection (usually organ sparing) constitutes the treatment of choice for localized disease[3,15,18,23,38,56]. Chemo-, immune- and/or radiotherapy have little efficacy[3,12,18,56,57].

Cytogenetic studies disclosed that the proteins encoded by the TSC1 (hamartin) and TSC2 (tuberin) genes are involved in cell proliferation and differentiation through the inhibition (negative regulation) of the mammalian target of the rapamycin (mTOR) kinase signalling pathway[58]. Thus, loss of heterozygosity of the TSC1 and mainly TSC2 genes[47] inactivates the tuberin/hamartin complex, leading to mTOR activation, further promoting translational initiation and cell growth[59]. Kenerson et al[47] discovered activation of the mTOR cascade in 15 out of 15 sporadic AML cases, while Pan et al[59] found loss of heterozygosity, leading to mTOR activation, in 11 out 12 PEComa patients. Activation of mTOR through loss of the TSC1/TSC2 complex seems to be a consistent and critically pathogenic event in PEComas[21,45], a finding that indicates a potential benefit from the use of mTOR inhibitors in patients with locally advanced, unresectable, metastatic or recurrent PEComas.

mTOR inhibitors act as cytostatic rather than cell death agents, regulating the cell cycle at the G1 phase[60], in several types of TSC1/TSC2 deficient cell lines in vitro[61]. Currently, the effectiveness of mTOR inhibitors on non-AML/non-pulmonary PEComas of advanced stage, at any localization, is limited. In the only available review, Dickson et al[4] reported complete response in 5, partial response in 1 and progression of disease in 5 out of 11 enrolled patients. Later, Wagner et al[21] reported clinical response in 2 out of 3 enrolled patients, and Starbuck et al[62] also noticed clinical response in 2 out of 3 enrolled patients, while Batereau et al[63] reported complete response in both patients treated.

TFE3 gene rearrangements are increasingly described in PEComas[64], seen in 9 out of 38 cases studied from broad spectrum locations[65]. Eighty percent of TFE3-negative PEComas harbour TSC2 mutations[65]. However, PEComas harbouring TFE3 gene rearrangements are thought to form a morphologically similar but biologically distinctive subgroup, as they lack the TSC2 alterations characteristic of conventional ones[66]. Lack of TSC2 involvement in TFE3 rearranged PEComas has been proposed as an explanation for the non-response to mTOR inhibitors[62,66].

In cases of retroperitoneal sarcomas, neoadjuvant chemotherapy is not the standard of care but can occasionally be considered when complete resection is uncertain[67]. The present review, however, disclosed that this strategy has been applied only once[4] in retroperitoneal PEComas.

Administration of mTOR inhibitors as adjuvant therapy may be beneficial for patients at high risk for recurrence. Although the present study disclosed that half of the potentially malignant retroperitoneal PEComas will develop metastases, the rarity of the disease does not allow conclusive results because the “cost-benefit” analysis remains a major concern.

An optimal routine follow-up policy is also not available for PEComa cases. We propose a sensible approach to following the sarcoma guidelines for follow-up[68]. Thus, high-risk patients may be followed every 3 mo for the first 3 years, then twice a year up to the fifth year and annually thereafter, while low-risk patients may be followed every 6 mo for the first 5 years and then annually.

Overall, 44 retroperitoneal PEComas have been reported in the English literature, making retroperitoneal space the third most frequent location for PEComas NOS development. Half were stratified as potentially malignant, and nearly half of the potentially malignant tumours presented with or developed metastases during the course of the disease. Thus, retroperitoneal PEComas are not as indolent as they are supposed to be. Radical surgical resection constitutes the treatment of choice for localized disease, while mTOR inhibitors constitute the most promising therapy for disseminated disease. The role of mTOR inhibitors as adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapies needs to be evaluated in the future.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Greece

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kaypaklı O, Liu J, Vento S S-Editor: Ma RY L-Editor: A E-Editor: Qi LL

| 1. | Folpe AL. Neoplasms with perivascular epithelioid cell differentiation (PEComas). In: Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F, editors. Pathology and genetics of tumours of soft tissue and bone. Lyon, France: IARC Press 2002; 221-222. |

| 2. | Amin MB. Epithelioid angiomyolipoma. In: Eble JN, Sauter G, Epstein JI, Sesterhenn IA, editors. Pathology and penetics Tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs. Lyon, France: IARC Press 2004; 68-69. |

| 3. | Martignoni G, Pea M, Reghellin D, Zamboni G, Bonetti F. PEComas: the past, the present and the future. Virchows Arch. 2008;452:119-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 337] [Cited by in RCA: 372] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dickson MA, Schwartz GK, Antonescu CR, Kwiatkowski DJ, Malinowska IA. Extrarenal perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComas) respond to mTOR inhibition: clinical and molecular correlates. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:1711-1717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Glasgow CG, Taveira-Dasilva AM, Darling TN, Moss J. Lymphatic involvement in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1131:206-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. PEComa: what do we know so far? Histopathology. 2006;48:75-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 341] [Cited by in RCA: 318] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bleeker JS, Quevedo JF, Folpe AL. "Malignant" perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasm: risk stratification and treatment strategies. Sarcoma. 2012;2012:541626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Venyo AK. A Review of the Literature on Extrarenal Retroperitoneal Angiomyolipoma. Int J Surg Oncol. 2016;2016:6347136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Minja EJ, Pellerin M, Saviano N, Chamberlain RS. Retroperitoneal extrarenal angiomyolipomas: an evidence-based approach to a rare clinical entity. Case Rep Nephrol. 2012;2012:374107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Heller MT, Haarer KA, Thomas E, Thaete FL. Neoplastic and proliferative disorders of the perinephric space. Clin Radiol. 2012;67:e31-e41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sun DZ, Campbell SC. Atypical Epithelioid Angiomyolipoma: A Rare Variant With Malignant Potential. Urology. 2018;112:20-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chen Z, Han S, Wu J, Xiong M, Huang Y, Chen J, Yuan Y, Peng J, Song W. A systematic review: perivascular epithelioid cell tumor of gastrointestinal tract. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e3890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kwon BS, Suh DS, Lee NK, Song YJ, Choi KU, Kim KH. Two cases of perivascular epithelioid cell tumor of the uterus: clinical, radiological and pathological diagnostic challenge. Eur J Med Res. 2017;22:7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Audard V, Dorel-Le Théo M, Trincard MD, Charitanski D, Selmas VB, Vieillefond A. [A large para-renal PEComa]. Ann Pathol. 2004;24:271-3; quiz 227. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Gunia S, Awwadeh L, May M, Roedel S, Kaufmann O. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) with perirenal manifestation. Int J Urol. 2005;12:489-492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Shin JS, Spillane A, Wills E, Cooper WA. PEComa of the retroperitoneum. Pathology. 2008;40:93-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Sclerosing PEComa: clinicopathologic analysis of a distinctive variant with a predilection for the retroperitoneum. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:493-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lans TE, van Ramshorst GH, Hermans JJ, den Bakker MA, Tran TC, Kazemier G. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor of the retroperitoneum in a young woman resulting in an abdominal chyloma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:389-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Koenig AM, Quaas A, Ries T, Yekebas EF, Gawad KA, Vashist YK, Burdelski C, Mann O, Izbicki JR, Erbersdobler A. Perivascular epitheloid cell tumour (PEComa) of the retroperitoneum - a rare tumor with uncertain malignant behaviour: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Subbiah V, Trent JC, Kurzrock R. Resistance to mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor therapy in perivascular epithelioid cell tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:e415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wagner AJ, Malinowska-Kolodziej I, Morgan JA, Qin W, Fletcher CD, Vena N, Ligon AH, Antonescu CR, Ramaiya NH, Demetri GD, Kwiatkowski DJ, Maki RG. Clinical activity of mTOR inhibition with sirolimus in malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumors: targeting the pathogenic activation of mTORC1 in tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:835-840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 269] [Cited by in RCA: 278] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Suemitsu R, Takeo S, Uesugi N, Inoue Y, Hamatake M, Ichiki M. A long-term survivor with late-onset-repeated pulmonary metastasis of a PEComa. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;16:429-431. [PubMed] |

| 23. | de León DC, Pérez-Montiel D, Bandera A, Villegas C, Gonzalez-Conde E, Vilchis JC. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor of abdominal origin. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2010;14:173-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kumar S, Lal A, Acharya N, Sharma V. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumour (PEComa) of the inferior vena cava presenting as an adrenal mass. Cancer Imaging. 2010;10:77-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Valiathan M, Sunil B, Rao L, Geetha V, Hedge P. Sclerosing PEComa: a histologic surprice. Afr J Urol. 2011;17:97-100. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Alguraan Z, Agcaoglu O, El-Hayek K, Hamrahian AH, Siperstein A, Berber E. Retroperitoneal masses mimicking adrenal tumors. Endocr Pract. 2012;18:335-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Santi R, Franchi A, Villari D, Paglierani M, Pepi M, Danielli D, Nicita G, Nesi G. Sclerosing variant of PEComa: report of a case and review of the literature. Histol Histopathol. 2012;27:1175-1181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Rekhi B, Sable M, Desai SB. Retroperitoneal sclerosing PEComa with melanin pigmentation and granulomatous inflammation-a rare association within an uncommon tumor. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2012;55:395-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Yang B, Wang L, Wu Z, Li M, Wang H, Sheng J, Huang J, Liao S, Sun Y. Synchronous transperitoneal laparoscopic resection of right retroperitoneal schwannoma and left kidney monotypic PEComa in the presence of a duplicated inferior vena cava (IVC). Urology. 2012;80:e7-e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Theodosopoulos T, Psychogiou V, Yiallourou AI, Polymeneas G, Kondi-Pafiti A, Papaconstantinou I, Voros D. Management of retroperitoneal sarcomas: main prognostic factors for local recurrence and survival. J BUON. 2012;17:138-142. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Wu JH, Zhou JL, Cui Y, Jing QP, Shang L, Zhang JZ. Malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumor of the retroperitoneum. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6:2251-2256. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Guglielmetti G, De Angelis P, Mondino P, Terrone C, Volpe A. PEComa of soft tissues can mimic lymph node relapse in patients with history of testicular seminoma. Can Urol Assoc J. 2013;7:E651-E653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Pata G, Tironi A, Solaini L, Tiziano T, Ragni F. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor located retroperitoneally with pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis: report of a case. Surg Today. 2014;44:572-576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Wildgruber M, Becker K, Feith M, Gaa J. Perivascular epitheloid cell tumor (PEComa) mimicking retroperitoneal liposarcoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Oh HW, Kim TH, Cha RR, Kim NY, Kim HJ, Jung WT, Lee OJ, Lee JH. [A case of malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumor of the retroperitoneum with multiple metastases]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2014;64:302-306. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Morosi C, Stacchiotti S, Marchianò A, Bianchi A, Radaelli S, Sanfilippo R, Colombo C, Richardson C, Collini P, Barisella M, Casali PG, Gronchi A, Fiore M. Correlation between radiological assessment and histopathological diagnosis in retroperitoneal tumors: analysis of 291 consecutive patients at a tertiary reference sarcoma center. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40:1662-1670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Nakanishi S, Miyazato M, Yonemori K, Tamashiro T, Yoshimi N, Saito S. [Perirenal malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumor originating from right retroperitoneum: a case report]. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2014;60:627-630. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Liang W, Xu C, Chen F. Primary retroperitoneal perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasm: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2015;10:469-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Bhanushali AH, Dalvi AN, Bhanushali HS. Laparoscopic excision of infra-renal PEComa. J Minim Access Surg. 2015;11:282-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | To VYK, Tsang JPK, Yeung TW, Yuen MK. Retroperitoneal sclerosing perivascular epithelioid cell tumour. Hong Kong J Radiol. 2015;18:51-56. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Danilewicz M, Strzelczyk JM, Wagrowska-Danilewicz M. Perirenal perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) coexisting with other malignancies: a case report. Pol J Pathol. 2017;68:92-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Cihan YB, Kut E, Koç A. Recurrence of retroperitoneal localized perivascular epithelioid cell tumor two years after initial diagnosis: case report. Sao Paulo Med J. 2019;137:206-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Singer E, Yau S, Johnson M. Retroperitoneal PEComa: Case report and review of literature. Urol Case Rep. 2018;19:9-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Stone CH, Lee MW, Amin MB, Yaziji H, Gown AM, Ro JY, Têtu B, Paraf F, Zarbo RJ. Renal angiomyolipoma: further immunophenotypic characterization of an expanding morphologic spectrum. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:751-758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Folpe AL, Kwiatkowski DJ. Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms: pathology and pathogenesis. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:1-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Ardeleanu C, Bussolati G. Telocytes are the common cell of origin of both PEComas and GISTs: an evidence-supported hypothesis. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:2569-2574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Kenerson H, Folpe AL, Takayama TK, Yeung RS. Activation of the mTOR pathway in sporadic angiomyolipomas and other perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms. Hum Pathol. 2007;38:1361-1371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Pleniceanu O, Omer D, Azaria E, Harari-Steinberg O, Dekel B. mTORC1 Inhibition Is an Effective Treatment for Sporadic Renal Angiomyolipoma. Kidney Int Rep. 2017;3:155-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Dabora SL, Jozwiak S, Franz DN, Roberts PS, Nieto A, Chung J, Choy YS, Reeve MP, Thiele E, Egelhoff JC, Kasprzyk-Obara J, Domanska-Pakiela D, Kwiatkowski DJ. Mutational analysis in a cohort of 224 tuberous sclerosis patients indicates increased severity of TSC2, compared with TSC1, disease in multiple organs. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:64-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 689] [Cited by in RCA: 664] [Article Influence: 27.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Tan Y, Zhang H, Xiao EH. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumour: dynamic CT, MRI and clinicopathological characteristics--analysis of 32 cases and review of the literature. Clin Radiol. 2013;68:555-561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Folpe AL, Mentzel T, Lehr HA, Fisher C, Balzer BL, Weiss SW. Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms of soft tissue and gynecologic origin: a clinicopathologic study of 26 cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1558-1575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 640] [Cited by in RCA: 636] [Article Influence: 33.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | McClymont K, Brown I, Hussey D. Test and teach. 53. Diagnosis: An interesting retroperitoneal mass. Pathology. 2007;39:164-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Lopez-Beltran A, Scarpelli M, Montironi R, Kirkali Z. 2004 WHO classification of the renal tumors of the adults. Eur Urol. 2006;49:798-805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 603] [Cited by in RCA: 622] [Article Influence: 32.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Nese N, Martignoni G, Fletcher CD, Gupta R, Pan CC, Kim H, Ro JY, Hwang IS, Sato K, Bonetti F, Pea M, Amin MB, Hes O, Svec A, Kida M, Vankalakunti M, Berel D, Rogatko A, Gown AM, Amin MB. Pure epithelioid PEComas (so-called epithelioid angiomyolipoma) of the kidney: A clinicopathologic study of 41 cases: detailed assessment of morphology and risk stratification. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:161-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Kudela E, Biringer K, Kasajova P, Nachajova M, Adamkov M. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumors of the uterine cervix. Pathol Res Pract. 2016;212:667-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Rutkowski PL, Mullen JT. Management of the "Other" retroperitoneal sarcomas. J Surg Oncol. 2018;117:79-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Musella A, De Felice F, Kyriacou AK, Barletta F, Di Matteo FM, Marchetti C, Izzo L, Monti M, Benedetti Panici P, Redler A, D'Andrea V. Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasm (PEComa) of the uterus: A systematic review. Int J Surg. 2015;19:1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Karbowniczek M, Henske EP. The role of tuberin in cellular differentiation: are B-Raf and MAPK involved? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1059:168-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Pan CC, Chung MY, Ng KF, Liu CY, Wang JS, Chai CY, Huang SH, Chen PC, Ho DM. Constant allelic alteration on chromosome 16p (TSC2 gene) in perivascular epithelioid cell tumour (PEComa): genetic evidence for the relationship of PEComa with angiomyolipoma. J Pathol. 2008;214:387-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Zhang CZ, Wang XD, Wang HW, Cai Y, Chao LQ. Sorafenib inhibits liver cancer growth by decreasing mTOR, AKT, and PI3K expression. J BUON. 2015;20:218-222. [PubMed] |

| 61. | Guertin DA, Sabatini DM. The pharmacology of mTOR inhibition. Sci Signal. 2009;2:pe24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 453] [Cited by in RCA: 460] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Starbuck KD, Drake RD, Budd GT, Rose PG. Treatment of Advanced Malignant Uterine Perivascular Epithelioid Cell Tumor with mTOR Inhibitors: Single-institution Experience and Review of the Literature. Anticancer Res. 2016;36:6161-6164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Batereau C, Knösel T, Angele M, Dürr HR, D'Anastasi M, Kampmann E, Ismann B, Bücklein V, Lindner LH. Neoadjuvant or adjuvant sirolimus for malignant metastatic or locally advanced perivascular epithelioid cell tumors: two case reports. Anticancer Drugs. 2016;27:254-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Thway K, Fisher C. PEComa: morphology and genetics of a complex tumor family. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2015;19:359-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Agaram NP, Sung YS, Zhang L, Chen CL, Chen HW, Singer S, Dickson MA, Berger MF, Antonescu CR. Dichotomy of Genetic Abnormalities in PEComas With Therapeutic Implications. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39:813-825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Malinowska I, Kwiatkowski DJ, Weiss S, Martignoni G, Netto G, Argani P. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComas) harboring TFE3 gene rearrangements lack the TSC2 alterations characteristic of conventional PEComas: further evidence for a biological distinction. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:783-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | van Houdt WJ, Zaidi S, Messiou C, Thway K, Strauss DC, Jones RL. Treatment of retroperitoneal sarcoma: current standards and new developments. Curr Opin Oncol. 2017;29:260-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Casali PG, Abecassis N, Aro HT, Bauer S, Biagini R, Bielack S, Bonvalot S, Boukovinas I, Bovee JVMG, Brodowicz T, Broto JM, Buonadonna A, De Álava E, Dei Tos AP, Del Muro XG, Dileo P, Eriksson M, Fedenko A, Ferraresi V, Ferrari A, Ferrari S, Frezza AM, Gasperoni S, Gelderblom H, Gil T, Grignani G, Gronchi A, Haas RL, Hassan B, Hohenberger P, Issels R, Joensuu H, Jones RL, Judson I, Jutte P, Kaal S, Kasper B, Kopeckova K, Krákorová DA, Le Cesne A, Lugowska I, Merimsky O, Montemurro M, Pantaleo MA, Piana R, Picci P, Piperno-Neumann S, Pousa AL, Reichardt P, Robinson MH, Rutkowski P, Safwat AA, Schöffski P, Sleijfer S, Stacchiotti S, Sundby Hall K, Unk M, Van Coevorden F, van der Graaf WTA, Whelan J, Wardelmann E, Zaikova O, Blay JY. ESMO Guidelines Committee and EURACAN. Soft tissue and visceral sarcomas: ESMO-EURACAN Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:iv51-iv67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 426] [Cited by in RCA: 459] [Article Influence: 65.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |