Published online Oct 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i20.3266

Peer-review started: June 4, 2019

First decision: August 1, 2019

Revised: August 23, 2019

Accepted: October 5, 2019

Article in press: October 5, 2019

Published online: October 26, 2019

Processing time: 151 Days and 8.6 Hours

Refractory ascites is a rare complication following orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT). The broad spectrum of differential diagnosis often leads to delay in diagnosis. Therapy depends on recognition and treatment of the underlying cause. Constrictive pericarditis is a condition characterized by clinical signs of right-sided heart failure. In the advanced stages of the disease, hepatic congestion leads to formation of ascites. In patients after OLT, cardiac etiology of ascites is easily overlooked and it requires a high degree of clinical suspicion.

We report a case of a 55-year-old man who presented with a refractory ascites three months after liver transplantation for alcoholic cirrhosis. Prior to transplantation the patient had a minimal amount of ascites. The transplant procedure and the early postoperative course were uneventful. Standard post-transplant work up failed to reveal any typical cause of refractory post-transplant ascites. The function of the graft was good. Apart from atrial fibrillation, cardiac status was normal. Eighteen months post transplantation the patient developed dyspnea and severe fatigue with peripheral edema. Ascites was still prominent. The presenting signs of right-sided heart failure were highly suggestive of cardiac etiology. Diagnostic paracentesis was suggestive of cardiac ascites, and further cardiac evaluation showed typical signs of constrictive pericarditis. Pericardiectomy was performed followed by complete resolution of ascites. On the follow-up the patient remained symptom-free with no signs of recurrent ascites and with normal function of the liver graft.

Refractory ascites following liver transplantation is a rare complication with many possible causes. Broad differential diagnosis needs to be considered.

Core tip: Refractory ascites following liver transplantation is a rare complication with many possible causes. Constrictive pericarditis is a disease characterized by clinical signs of right-sided heart failure which in the advanced stages can lead to hepatic congestion and formation of ascites. As a cause of refractory ascites it is easily overlooked and it requires a high degree of clinical suspicion. We present an uncommon case where refractory ascites occurred after successful liver transplantation for alcoholic cirrhosis and was caused by previously unknown constrictive pericarditis. Pericardiectomy led to complete resolution of the ascites, and the patient remained symptom free until today.

- Citation: Bezjak M, Kocman B, Jadrijević S, Gašparović H, Mrzljak A, Kanižaj TF, Vujanić D, Bubalo T, Mikulić D. Constrictive pericarditis as a cause of refractory ascites after liver transplantation: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(20): 3266-3270

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i20/3266.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i20.3266

Refractory ascites is a rare complication following orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT). It is defined as persistent ascites present for more than four weeks after a successful transplantation. It occurs in about 5% of patients after OLT and it is associated with reduced 1-year survival. Etiology may be diverse with the most common underlying causes being bacterial peritonitis, obstruction of portal or hepatic veins, graft rejection, and renal or cardiac dysfunction. Therapy depends on recognition and treatment of the underlying cause[1-4]. Constrictive pericarditis is a condition characterized by clinical signs of chronic right-sided heart failure, including peripheral edema and liver congestion. In the advanced stages of the disease, hepatic congestion leads to formation of ascites, as well as liver fibrosis and cirrhosis (cardiac cirrhosis). In patients after OLT, cardiac etiology of ascites is easily overlooked and it requires a high degree of clinical suspicion[5-8].

The purpose of this case report is to summarize the cases of refractory ascites caused by constrictive pericarditis that have been published to date, to evaluate the results and analyze the approach in differential diagnosis. Also, we present an uncommon case where refractory ascites caused by constrictive pericarditis occured in patient with a transplanted liver. A Pubmed literature search was performed for studies dealing with refractory ascites caused by constrictive pericarditis published between 2000 and 2018. Key words used were constrictive pericarditis, refractory ascites, reccurent ascites, liver transplantation, ascitic fluid, pericardiectomy. Only studies published in English were analyzed.

A 55-year-old caucasian man underwent OLT for alcoholic cirrhosis. Prior to transplantation the patient only had a minimal amount of ascites. Apart from atrial fibrillation he had no other comorbidities. The transplant procedure and the early postoperative course were uneventful. The patient was discharged home on the 9th post-operative day with normal liver function tests and in good general condition. Three months post transplantation he presented with prominent ascites resistant to conventional diuretic treatment.

All of the typical causes of post-transplant ascites were initially excluded. There were no signs of bacterial peritonitis, and paracentesis revealed ascitic fluid to be transudate. Doppler ultrasound and computed tomography were normal, showing patent anastomoses and no other morphological or vascular abnormalities. Liver biopsy showed no signs of graft failure or rejection. Liver function tests and other laboratory values were within normal limits. Apart from atrial fibrillation, there were no abnormalities in the cardiac status. Heart ultrasound showed mild mitral insufficiency with a slightly elevated pressure in the right ventricle. The ascites was explained by poorly regulated atrial fibrillation aggravated by mild anemia which upon correction improved slightly.

Apart from atrial fibrillation the patient had no significant past medical history prior to transplantation.

The patient had no significant personal or family history.

Eighteen months post transplantation he developed dyspnea with severe fatigue and peripheral edema with prominent ascites and a significant weight gain. The presenting signs of right-sided heart failure were highly suggestive of cardiac etiology.

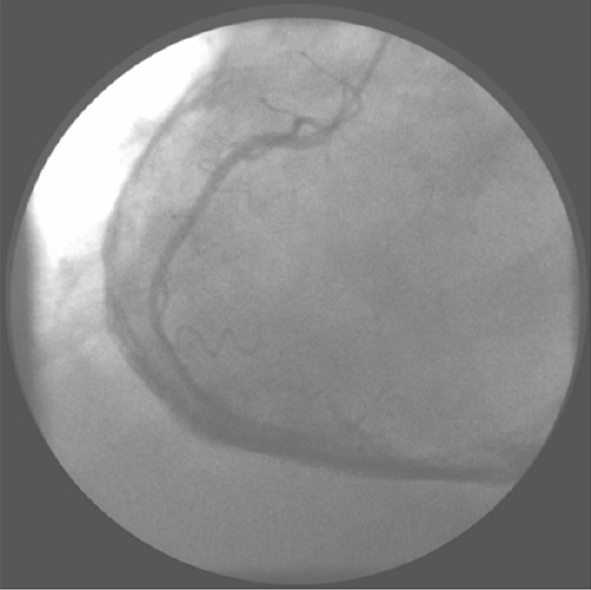

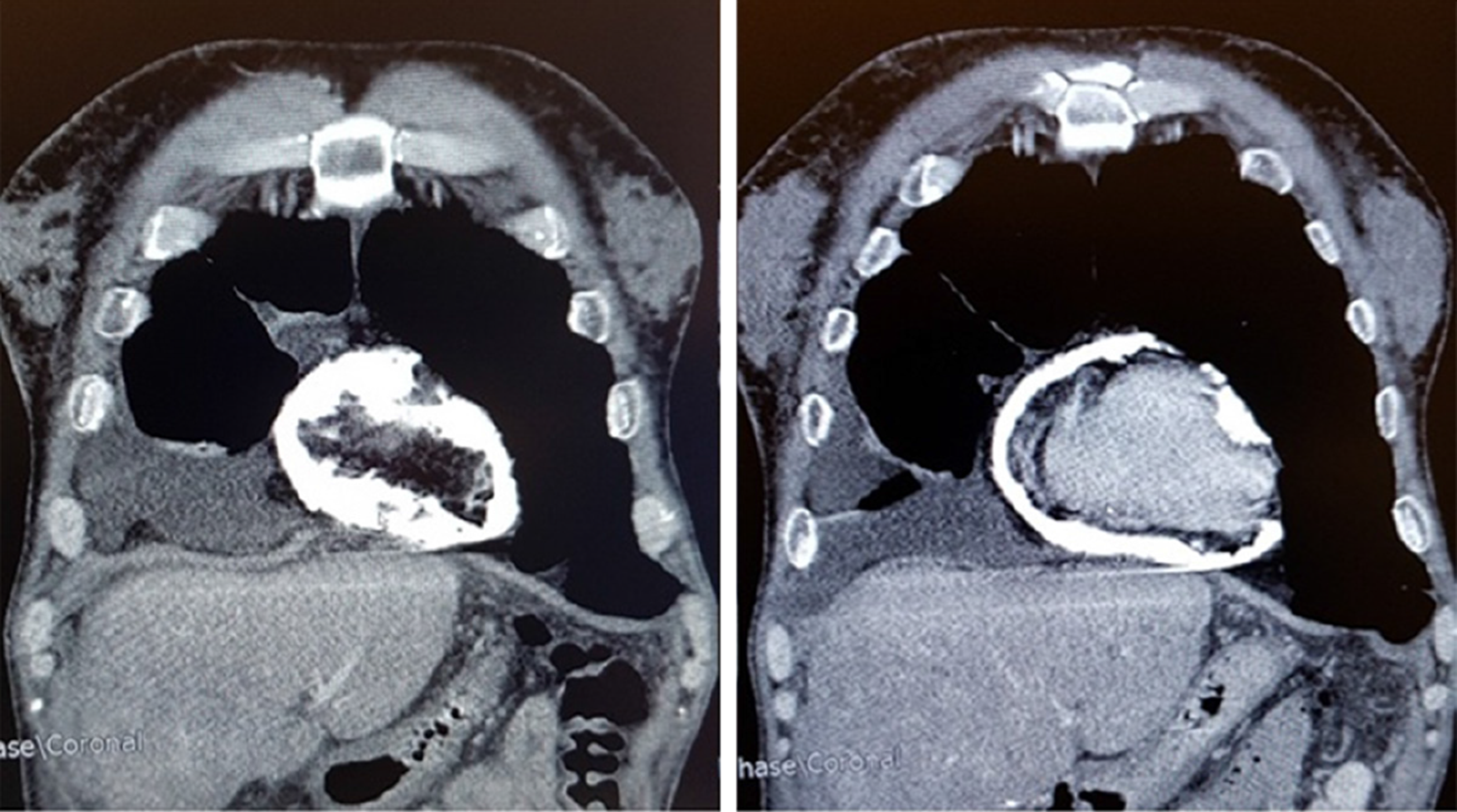

Cardiac catheterisation revealed slightly elevated pressures in all four chambers and equalization of diastolic chamber pressures also known as the square root sign. This is the typical presentation of constrictive pericarditis and computed tomography showed excessive pericardial calcifications (Figures 1 and 2). The patient underwent an open pericardiectomy. The procedure was complicated by acute kidney injury which required intermittent hemodialysis. This was followed by improvement of the patient’s general condition as well as of his renal function. There were no other complications related to the procedure. Following pericardiectomy, ascites improved dramatically with complete regression of all symptoms. On the follow-up the patient remained symptom-free with no signs of recurrent ascites and with normal function of the liver graft.

Constrictive pericarditis.

Total pericardiectomy.

After total pericardiectomy ascites improved dramatically with complete regression of all symptoms. On the follow-up the patient remained symptom-free with no signs of recurrent ascites and with normal function of the liver graft.

Refractory ascites after OLT is a rare complication occurring in about 5% of patients and it is usually a complication of the transplant procedure. The difficulties in the differential diagnosis of refractory ascites have been described and a delay in diagnosis is common[6-10]. Most common underlying causes are bacterial or fungal peritonitis, obstruction of the portal or hepatic veins and graft rejection. Patients with refractory ascites after liver transplantation often have prolonged hospital stay and reduced 1-year survival. The treatment should be directed at the cause of ascites[1,2]. In cases without an obvious cause of ascites, splenic artery embolization has been described as a good therapeutic measure improving intrahepatic hemodynamics after liver transplantation[2]. Constrictive pericarditis is a rare cause of refractory ascites after liver transplantation. There are also several case reports describing constrictive pericarditis after renal transplantation leading both to graft dysfunction and liver disease[11]. This disease of the pericardium was described as concretio cordis over 300 years ago and it is characterized by fibrosis and thickening of the pericardial wall and calcifications of the pericardium[5]. Due to the heart constriction, diastolic filling is impaired. The myocardium is not affected and early diastolic filling of the ventricle is normal, however, at one point the thickened pericardium prevents the ventricle from further expansion and restricts the cardiac blood flow. Disturbance of the blood flow leads to equalization of pressures in the right and left ventricles and higher pressure exerted on the interventricular septum, thus increasing the pressure in the splanchnic system. This explains the common clinical phenomenon, Kussmaul's sign, inspiratory distention of jugular veins. The most common etiology of constrictive pericarditis includes heart surgery, radiation therapy and idiopathic pericarditis. Tuberculosis remains an important etiological factor in undeveloped countries. Clinical presentation of the illness is characterized by the signs of right-sided heart failure, peripheral edema and hepatic congestion. In advanced stages, hepatic congestion can progress into fibrosis and cirrhosis, also known as cardiac cirrhosis, manifesting with edema and jaundice. Severe muscle wasting and cachexia are also described[5-7]. In some studies, ascites was present in 45% of patients with constrictive pericarditis[5]. Differential diagnosis includes right-sided heart failure due to restrictive cardiomyopathy, inferior vena cava obstruction, tricuspid valve dysfunction, hepatic diseases, abdominal malignancies and some rare causes such as right atrial myxoma[5,6]. Analysis of the ascites may be helpful, with a unique pattern associated with constrictive pericarditis. Relatively high serum-ascitic fluid albumin gradient (SAAG) above 1.1 g/dL and total protein concentration greater than 2.5 g/dL makes it an exudate with high SAAG. Such levels of total protein count are also typical of other postsinusoidal causes of ascites, in comparison with cirrhotic ascites which is usually a transudate with lower total protein count and high SAAG[12,13]. Echocardiography is the initial imaging method. The criteria pointing to the diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis include thickened pericardium, inspiratory shift of interventricular septum to the left described as “septal bounce“ due to pressure changes in the heart, non-collapsing inferior vena cava and reduced diastolic filling. Cardiac catheterization is considered the gold standard in the diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis. Simultaneous catheterization of both ventricles shows equalization of diastolic chamber pressures[5-8]. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are useful non-invasive diagnostic tools with excellent sensitivity (88%) and specificity (100%). They allow for direct visualization of the pericardial thickening and calcifications[7]. Pericardiectomy is the treatment of choice for symptomatic and severe constrictive pericarditis with surgical mortality of 6% and 7-year survival of about 88%[14,15].

Refractory ascites is a rare complication occurring after liver transplantation. Etiology is diverse, and if typical causes related to the transplantation are excluded, more uncommon reasons need to be considered. Constrictive pericarditis is a common cause of refractory ascites, however, only rarely described after liver transplantation. Good outcome of total pericardiectomy in the presented case underlines the importance of a correct and timely diagnosis.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: Croatia

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ramsay MA, Bramhall S S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: A E-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Gotthardt DN, Weiss KH, Rathenberg V, Schemmer P, Stremmel W, Sauer P. Persistent ascites after liver transplantation: etiology, treatment and impact on survival. Ann Transplant. 2013;18:378-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Runyon BA; AASLD Practice Guidelines Committee. Management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis: an update. Hepatology. 2009;49:2087-2107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 628] [Cited by in RCA: 613] [Article Influence: 38.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Quintini C, D'Amico G, Brown C, Aucejo F, Hashimoto K, Kelly DM, Eghtesad B, Sands M, Fung JJ, Miller CM. Splenic artery embolization for the treatment of refractory ascites after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2011;17:668-673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Saad WE, Darwish WM, Davies MG, Waldman DL. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts in liver transplant recipients for management of refractory ascites: clinical outcome. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21:218-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bergman M, Vitrai J, Salman H. Constrictive pericarditis: A reminder of a not so rare disease. Eur J Intern Med. 2006;17:457-464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lominadze Z, Kia L, Shah S, Parekh K, Levitsky J. Constrictive Pericarditis as a Cause of Refractory Ascites. ACG Case Rep J. 2015;2:175-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Howard JP, Jones D, Mills P, Marley R, Wragg A. Recurrent ascites due to constrictive pericarditis. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2012;3:233-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Van der Merwe S, Dens J, Daenen W, Desmet V, Fevery J. Pericardial disease is often not recognised as a cause of chronic severe ascites. J Hepatol. 2000;32:164-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kamio T, Hiraoka E, Obunai K, Watanabe H. Constrictive Pericarditis as a Long-term Undetermined Etiology of Ascites and Edema. Intern Med. 2018;57:1487-1491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Domingos Nunes GF, Fatela N, Ramalho F. Long-evolution ascites in a patient with constrictive pericarditis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2016;108:368-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Celebi ZK, Keven K, Sengul S, Sayin T, Yazicioglu L, Tuzuner A, Erturk S, Duman N, Erbay B. Constrictive pericarditis after renal transplantation: three case reports. Transplant Proc. 2013;45:953-955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Christou L, Economou M, Economou G, Kolettis TM, Tsianos EV. Characteristics of ascitic fluid in cardiac ascites. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:1102-1105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Giallourakis CC, Rosenberg PM, Friedman LS. The liver in heart failure. Clin Liver Dis. 2002;6:947-967, viii-viix. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bertog SC, Thambidorai SK, Parakh K, Schoenhagen P, Ozduran V, Houghtaling PL, Lytle BW, Blackstone EH, Lauer MS, Klein AL. Constrictive pericarditis: etiology and cause-specific survival after pericardiectomy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1445-1452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 298] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chowdhury UK, Subramaniam GK, Kumar AS, Airan B, Singh R, Talwar S, Seth S, Mishra PK, Pradeep KK, Sathia S, Venugopal P. Pericardiectomy for constrictive pericarditis: a clinical, echocardiographic, and hemodynamic evaluation of two surgical techniques. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:522-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |