Published online Sep 26, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i27.108923

Revised: May 21, 2025

Accepted: June 17, 2025

Published online: September 26, 2025

Processing time: 102 Days and 1.2 Hours

Leiomyomas or fibroids commonly originate from the uterus; extrauterine leiomyomas are rare and most often arise from the broad ligament. Diagnosing broad ligament leiomyomas becomes particularly challenging when they undergo degenerative changes because their clinical and radiological features often mimic those of ovarian tumors. We report a rare case of a giant broad ligament fibroid with cystic degeneration, which was initially mistaken for an ovarian mass.

A 49-year-old woman presented with mild abdominal distension and pain as the only symptoms. Upon abdominal examination, a large mass measuring approximately 30 cm and extending from the pelvic cavity to just below the xiphoid process was identified. Both transvaginal ultrasound and contrast-enhanced computed tomography suggested an ovarian origin of the mass. However, laparotomy confirmed that the mass originated from the right broad ligament. The mass was separated from the uterus and bilateral ovaries, with no involve

Broad ligament myomas mimic ovarian tumors; accurate diagnosis and careful operation are critical to avoid complications and ensure safety.

Core Tip: This case highlights the diagnostic challenges posed by giant broad ligament fibroids, particularly in the presence of elevated cancer antigen 125 levels mimicking ovarian malignancy. Comprehensive imaging and histopathological evaluation remain critical for accurate diagnosis and surgical planning.

- Citation: Huang X, Yao Q, Wu YC, Liu SC. Diagnostic and surgical management of giant broad ligament myoma with cystic degeneration: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(27): 108923

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i27/108923.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i27.108923

Uterine leiomyomas occur in 20%-30% of women over the age of 35[1]. Depending on the tumor’s size and location, uterine fibroids may either remain asymptomatic or lead to symptoms such as abnormal uterine bleeding, anemia, pelvic pain, or pressure[2]. While most leiomyomas are located within the uterine body, they can also develop in other regions, such as the cervix or the broad ligament[3]. Broad ligament leiomyomas, however, account for only 6% to 10% of all uterine fibroids[4]. Although often asymptomatic[4], larger broad ligament fibroids can result in symptoms such as abdominal distension, abdominal pain, frequent urination, and constipation, often delaying diagnosis and treatment for many patients.

Cystic or degenerative changes are frequently observed in giant leiomyomas, further complicating preoperative differentiation from other pelvic pathologies. While advanced imaging modalities, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), play a crucial role in the diagnostic process, definitive confirmation typically relies on intraoperative assessment and histopathological evaluation.

Given the rarity of broad ligament leiomyomas, especially those presenting with atypical features such as cystic degeneration, case reports are essential for expanding the understanding of their clinical behavior and management. Herein, we describe a unique case of a giant broad ligament leiomyoma with cystic degeneration, highlighting its clinical presentation, diagnostic challenges, and surgical management. This case underscores the importance of including broad ligament leiomyomas in the differential diagnosis of complex pelvic masses and contributes valuable insights to the existing literature.

A 49-year-old woman presented to the surgical department with a 2-month history of lower abdominal pain and discomfort.

The patient experienced only mild, intermittent abdominal distension and pain in the lower abdomen for 2 months. She denied fever, weight loss, loss of appetite, night sweats, changes in bowel or bladder habits, rectal bleeding, or abnormal vaginal bleeding.

The patient’s medical history was notable only for two elective cesarean sections. She had not undergone routine physical examinations and reported no other significant medical history.

The patient was gravida 3, para 2, with one artificial termination of pregnancy. Her last childbirth occurred 30 years prior. She reported regular menstrual cycles with average pain and flow prior to menopause. The patient denied a history of smoking, alcohol consumption, substance abuse. She also reported no known drug or food allergies. Her dietary history indicated a preference for a balanced diet without significant dietary restrictions or notable deficiencies.

The patient’s family history was unremarkable, with no reported cases of gynecological malignancies, genetic disorders, or other hereditary conditions. There was no known history of uterine fibroids, ovarian tumors, or other relevant familial health issues.

The patient’s body mass index was 25.7 kg/m2, classifying her as overweight. Her general condition was fair, with no signs of icterus or pallor. Abdominal palpation revealed a large, firm-to-hard, nontender mass with restricted mobility extending from the pelvis to the xiphisternum. Vaginal examination indicated a smooth cervix, with pain on lifting. The uterus could not be distinguished from the mass, and bilateral forniceal fullness was noted.

Tumor markers, including cancer antigen (CA) 15-3, CA 19-9, β-human chorionic gonadotropin, carcinoembryonic antigen, and alpha-fetoprotein, were within the reference range. However, CA-125 was elevated at 107.56 IU/mL (normal range: 0.00–35.00 IU/mL), and HE4 was 63.21 pmol/L (normal range: 0.00–76.33 pmol/L).

Lower abdominal ultrasound revealed a retroverted uterus with an anteroposterior diameter of approximately 6.2 cm and no abnormal blood flow. A large, well-defined, mixed cystic-solid mass measuring 23 cm × 17 cm × 26 cm and spot-like blood flow signals were identified in the lower abdomen. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a large cystic-solid mass in the middle and lower abdomen and pelvis, measuring approximately 24 cm × 18 cm × 26 cm, with clear boundaries and predominantly cystic components. The lesion was closely associated with the right adnexa, and minimal fluid accumulation was noted in the lower abdomen and pelvic cavity. The mass caused intestinal compression and displacement, partial small intestine dilatation and fluid accumulation, and right ureter thinning. The radiological features raised suspicion of an ovarian tumor, particularly serous cystadenocarcinoma of right adnexal origin, as a primary differential diagnosis (Figure 1).

The preliminary diagnosis at the time of admission was a pelvic mass, with considerations of ovarian malignancy or other potential etiologies. After completing all auxiliary examinations, a multidisciplinary discussion was conducted with the relevant departments prior to surgery. The urologists carefully reviewed the CT findings and concluded that preoperative ureteral stent placement could be deferred. They recommended intraoperative consultation with the urology team, if necessary, to provide assistance during the procedure.

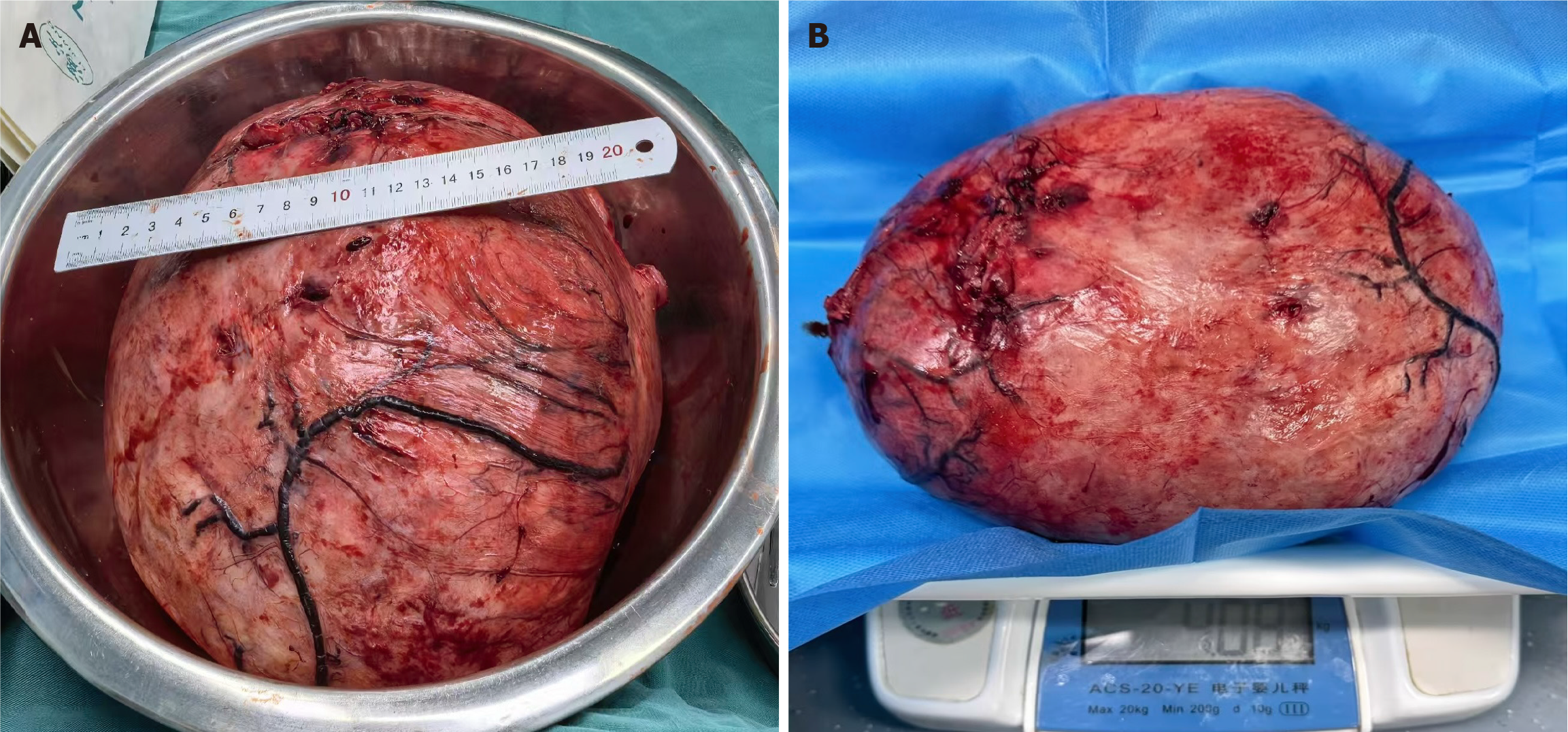

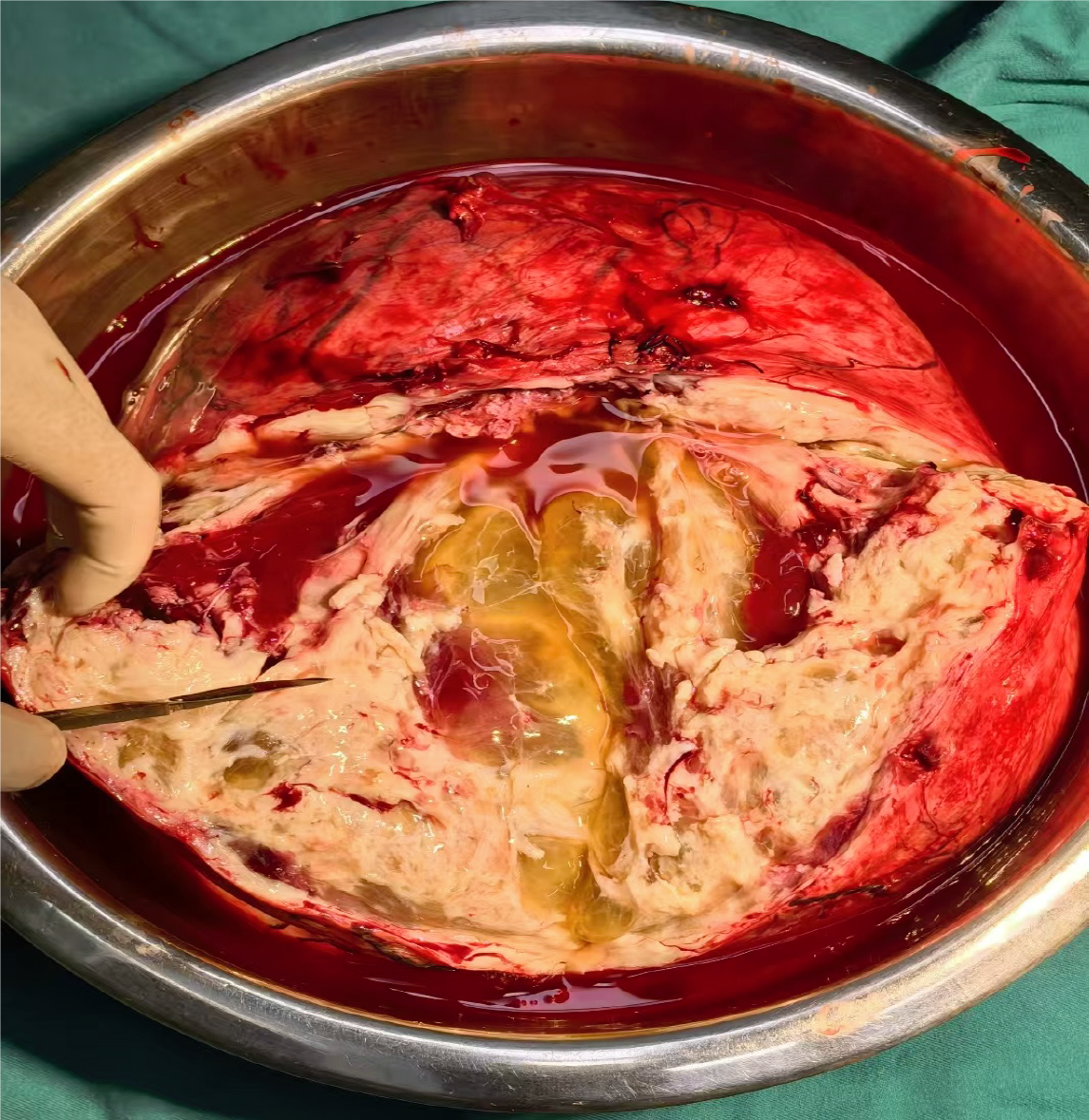

The patient underwent a planned laparotomy via a midline longitudinal incision. A large, tense mass that exhibited high surface tension was identified within the pelvic cavity. Under sterile conditions, puncture and aspiration were performed at the point of the highest tension, and approximately 1000 mL of light-yellow fluid was aspirated. The mass was subsequently sutured to restore anatomical integrity (Figure 2). Following decompression, the mass volume decreased, allowing for a considerably expanded surgical field.

The mass exhibited dilated surface blood vessels and was confirmed to originate from the right broad ligament (Figure 3). After decompression, the dimensions of the mass were approximately 22 cm × 20 cm × 15 cm (Figure 4). The mass was meticulously excised after freeing and preserving the ureter. The excised mass weighed approximately 4 kg (Figure 5).

Intraoperative frozen-section analysis indicated leiomyoma with cystic degeneration.

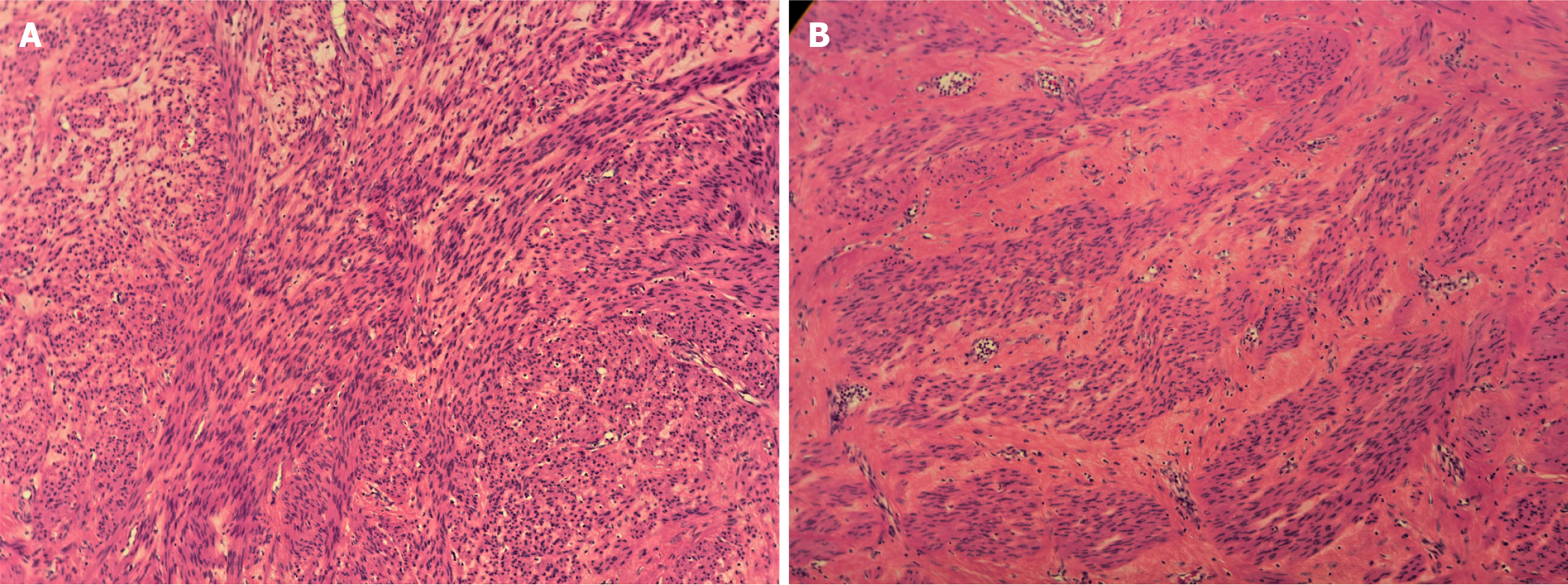

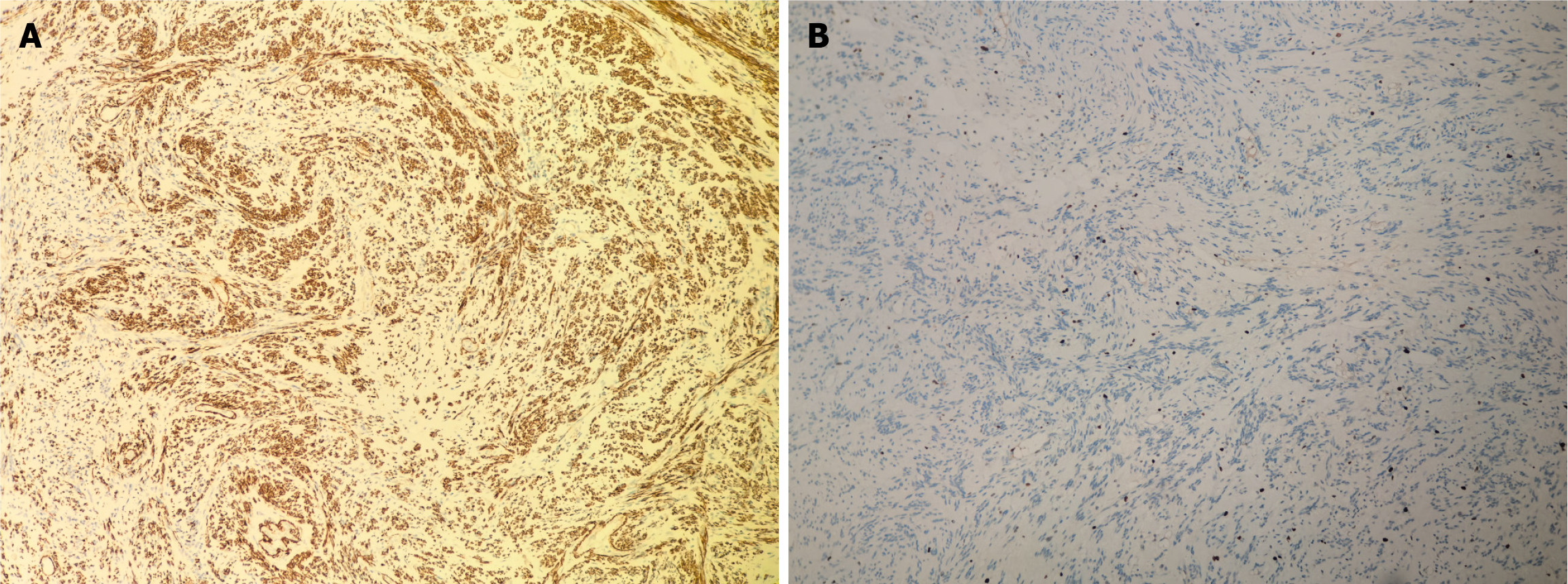

Following the patient’s and family’s wishes, the uterus and bilateral adnexa were preserved. The abdominal wound was sutured meticulously before closure. Postoperative examination revealed a multilocular cystic tumor containing significant fluid content (Figure 6). Postoperative specimens were subjected to hematoxylin–eosin staining, with an initial diagnosis of a leiomyogenic tumor (Figure 7). Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that the tumor cells were positive for SMA, caldesmon, desmin, ER, PR, FH, and vimentin, partially weakly positive for P53, and negative for CD117, DOG-1, CD34, S-100, SOX10, and STAT6. The Ki-67 proliferation index was approximately 1% (Figure 8). Based on the immunophenotype, the final diagnosis of leiomyoma with degeneration was confirmed.

No complications were noted during a 3-month follow-up.

Large abdominal masses can be categorized by their anatomical origins into intraperitoneal, retroperitoneal, and metastatic lesions. Primary retroperitoneal tumors commonly include mesenchymal neoplasms (e.g., liposarcoma, leiomyosarcoma), neurogenic tumors (e.g., schwannoma, paraganglioma), germ cell tumors (e.g., teratoma), and lymphomas[5]. Intraperitoneal masses frequently involve gastrointestinal sources (e.g., gastrointestinal stromal tumors, colorectal cancer), gynecological organs (e.g., ovarian tumors, uterine sarcoma), or the urinary system tumors (e.g., bladder cancer, renal cell carcinoma). Differential diagnosis relies heavily on imaging studies. Characteristically, retroperitoneal tumors demonstrate mass effect displacing retroperitoneal viscera (kidneys, ureters, great vessels) while maintaining a distinct plane of separation from intraperitoneal structures[6]. In the present case, imaging findings initially suggested a gynecological intraperitoneal neoplasm. Subsequent histopathological evaluation of the surgical specimen confirmed the diagnosis of a rare true broad ligament leiomyoma.

Broad ligament leiomyomas are categorized as false broad ligament fibroids, which are uterine tumors that extend into the broad ligament, and true broad ligament fibroids, which originate from the broad ligament’s subperitoneal connective tissue[7]. False broad ligament fibroids are located on the inside of the ureter and uterine blood vessels. Because of their rich blood supply, these tumors can grow to substantial sizes and undergo secondary changes, such as degeneration and necrosis. The differential diagnosis of broad ligament fibroids includes ovarian masses (both primary and metastatic tumors), broad ligament cysts, and lymphadenopathy. Our patient had a true broad ligament fibroid because it was anatomically separate from the uterus and adnexa and arose independently within the ligament itself.

Transvaginal ultrasonography, commonly used to assess pelvic masses, is often helpful in diagnosing broad ligament fibroids, as it allows for clear visualization of the uterus and ovaries relative to the mass[8]. However, diagnosing broad ligament fibroids preoperatively can be challenging; in our patient, the size of the mass obscured its origin. Although CT imaging can define the site and extent of the mass, MRI offers superior soft tissue characterization and is better at distinguishing broad ligament fibroids from other pelvic masses, including solid malignancies[8].

In our patient, MRI was not performed due to resource limitations and the patient’s financial constraints, representing a significant diagnostic limitation. Misdiagnosing atypical leiomyomas as malignant tumors can lead to unnecessary extensive surgeries and potential loss of uterine function, which might otherwise be avoided through less invasive procedures or nonsurgical treatments[9]. MRI is particularly valuable in such cases due to its high negative predictive value for benign leiomyomas and its ability to characteristic imaging features of leiomyomas, such as whorled and homogeneous low T2-weighted signal intensity[10,11]. The absence of MRI in our patient thus underscored a potential gap in optimizing the diagnostic and therapeutic pathway.

The patient’s mildly elevated CA-125 Levels further complicated the diagnostic process, initially leading to a misdiagnosis of metastatic ovarian cancer. Although CA-125 is most commonly associated with epithelial ovarian malignancies, it lacks specificity and may be elevated in various benign conditions[12]. Large uterine fibroids, including broad ligament fibroids, may cause CA-125 elevation through mechanical compression or traction on the peritoneum, leading to peritoneal irritation or mild inflammatory reactions. The likelihood of elevated CA-125 Levels increases with the size of the fibroid[13]. This phenomenon, often associated with pseudo-Meigs syndrome[14], can make the preoperative differentiation of benign lesions from malignant masses challenging.

Similar challenges have been documented, where benign gynecological conditions, such as fibroids and endometriosis, resulted in elevated CA-125 Levels, mimicking malignancy and leading to diagnostic errors[15]. For instance, a case report described a giant broad ligament fibroid with significantly elevated CA-125 Levels, initially suspected as advanced ovarian cancer, but later confirmed as benign upon histopathological examination[16].

Surgical excision remains the definitive treatment for broad ligament fibroids. Intraoperative frozen-section analysis is recommended to rule out malignancy; however, its accuracy is limited, and a definitive diagnosis often relies on the postoperative paraffin-section report[7].

Broad ligament fibroids present unique surgical challenges due to their location and proximity to vital pelvic structures. In our patient, the mass occupied the entire lower abdominal and pelvic cavity demonstrating marked cystic degeneration with tension. To reduce the tumor size and expand the surgical field, the mass was decompressed by aspirating approximately 1000 mL of light-yellow fluid at the point of highest tension. Subsequent inspection revealed dilated blood vessels on the tumor’s surface. Given the rich vascular supply of the broad ligament and its close proximity to the ureter and uterine vasculature, complications such as ureteral or uterine vessel injury and the formation of occult hematomas are among the most common intraoperative risks[17,18]. In this case, meticulous surgical dissection and careful identification and preservation of the ureter and adjacent structures allowed for the successful removal of the entire broad ligament myoma without significant complications.

The patient’s uterus and bilateral adnexa were preserved with respecting the patient’s desire. The intraoperative frozen-section analysis confirmed that the tumor was benign. Conservative surgery for broad ligament fibroids is associated with a high risk of complications, including pelvic sidewall hematoma, thermal injury to the colon, postoperative hypotension, incisional hernia, peritoneal hemorrhage requiring reoperation or rehospitalization, incisional cellulitis, and inadvertent salpingo-oophorectomy due to adhesions[15]. However, in this case, the patient experienced no postoperative complications. A follow-up abdominal ultrasound 1 month after surgery revealed no abnormalities.

Giant broad ligament myomas are rare and have varied presentation. Clinically and radiologically, they mimic ovarian malignancies, especially when cystic degeneration is present. In this case, the patient experienced only mild, intermittent abdominal distension and pain two months before admission. The diagnostic challenges included the lesion’s specific location, its massive size with accompanying cystic changes, and a mild elevation of CA-125. Surgical excision remains the definitive method for both the diagnosis and treatment of broad ligament myomas. Due to the narrowed surgical field and the anatomical distortion caused by the large lesion, careful surgical planning is essential. When necessary, preoperative ureteral stenting should be considered to help prevent injury to the ureter and surrounding structures, thereby minimizing surgical risks. The present case highlights the importance of considering broad ligament leiomyoma as a differential diagnosis for adnexal masses with both cystic and solid components. Additionally, careful surgical planning and techniques are essential to minimize potential harm to adjacent organs and ensure patient safety.

We express our gratitude to all colleagues who provided encouragement and constructive feedback during the course of this study.

| 1. | Fasih N, Prasad Shanbhogue AK, Macdonald DB, Fraser-Hill MA, Papadatos D, Kielar AZ, Doherty GP, Walsh C, McInnes M, Atri M. Leiomyomas beyond the uterus: unusual locations, rare manifestations. Radiographics. 2008;28:1931-1948. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 250] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Giuliani E, As-Sanie S, Marsh EE. Epidemiology and management of uterine fibroids. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2020;149:3-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 375] [Cited by in RCA: 303] [Article Influence: 60.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Awiwi MO, Badawy M, Shaaban AM, Menias CO, Horowitz JM, Soliman M, Jensen CT, Gaballah AH, Ibarra-Rovira JJ, Feldman MK, Wang MX, Liu PS, Elsayes KM. Review of uterine fibroids: imaging of typical and atypical features, variants, and mimics with emphasis on workup and FIGO classification. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2022;47:2468-2485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Huang PS, Sheu BC, Huang SC, Chang WC. Intraligamental Myomectomy Strategy Using Laparoscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23:954-961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gulati V, Swarup MS, Kumar J. Solid Primary Retroperitoneal Masses in Adults: An Imaging Approach. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2022;32:235-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Porrello G, Cannella R, Randazzo A, Badalamenti G, Brancatelli G, Vernuccio F. CT and MR Imaging of Retroperitoneal Sarcomas: A Practical Guide for the Radiologist. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sabbagh M, Almadloush H, Adwan D, Allahham O, Tomah B. Case report of preservative management of a giant broad ligament fibroid: A challenge in diagnosis and surgery. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2025;127:110888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rajanna DK, Pandey V, Janardhan S, Datti SN. Broad ligament fibroid mimicking as ovarian tumor on ultrasonography and computed tomography scan. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2013;3:8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Smith J, Zawaideh JP, Sahin H, Freeman S, Bolton H, Addley HC. Differentiating uterine sarcoma from leiomyoma: BET(1)T(2)ER Check! Br J Radiol. 2021;94:20201332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Omary RA, Vasireddy S, Chrisman HB, Ryu RK, Pereles FS, Carr JC, Resnick SA, Nemcek AA Jr, Vogelzang RL. The effect of pelvic MR imaging on the diagnosis and treatment of women with presumed symptomatic uterine fibroids. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2002;13:1149-1153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kubik-Huch RA, Weston M, Nougaret S, Leonhardt H, Thomassin-Naggara I, Horta M, Cunha TM, Maciel C, Rockall A, Forstner R. European Society of Urogenital Radiology (ESUR) Guidelines: MR Imaging of Leiomyomas. Eur Radiol. 2018;28:3125-3137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Felder M, Kapur A, Gonzalez-Bosquet J, Horibata S, Heintz J, Albrecht R, Fass L, Kaur J, Hu K, Shojaei H, Whelan RJ, Patankar MS. MUC16 (CA125): tumor biomarker to cancer therapy, a work in progress. Mol Cancer. 2014;13:129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 315] [Cited by in RCA: 357] [Article Influence: 32.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zou L, Lou J, Huang H, Xu L. Pseudo-Meigs syndrome caused by a rapidly enlarging hydropic leiomyoma with elevated CA125 levels mimicking ovarian malignancy: a case report and literature review. BMC Womens Health. 2024;24:445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yaguchi A, Ban K, Koshida Y, Fujikami Y, Ogura E, Terada A, Akagi K, Matsumoto H, Tobiume T, Okagaki A, Tatsumi K. Pseudo-Meigs Syndrome Caused by a Giant Uterine Leiomyoma with Cystic Degeneration: A Case Report. J Nippon Med Sch. 2020;87:80-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Badiner N, Fenster T. Incidence, Diagnosis and Treatment of Broad Ligament Fibroids in Women Undergoing Minimally Invasive (MIS) Myomectomy: A Chart Review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:S113-S114. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Abdelgawad M, Barghuthi L, Davis T, Omar M, Kamel OM, Gibbons J, Ragoza Y, Ismael H. Large uterine leiomyoma presenting as pseudo-Meigs' syndrome with an elevated ca125: a case report and literature review. J Surg Case Rep. 2022;2022:rjac253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kindinger LM, Setchell TE, Miskry TS. Broad ligament fibroids—a radiological and surgical challenge. Gynecol Surg. 2014;11:19-22. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 18. | Sakanaka M, Kohno K, Arai Y, Nishida M. Management of Seven Cases of Broad Ligament Fibroids Via Laparoscopic Surgery. Japan J Gynecol Obstet Endosc. 2013;29:79-83. [DOI] [Full Text] |