Published online Aug 26, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i24.105244

Revised: April 1, 2025

Accepted: May 13, 2025

Published online: August 26, 2025

Processing time: 145 Days and 17.7 Hours

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare and aggressive skin cancer with high incidence in older and immunocompromised patients. Its occurrence in the nasal dorsum is extremely rare and poses significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.

We report the case of a 65-year-old woman with diabetes mellitus and hyper

This case highlights the importance of considering MCC in the differential diagnosis of nasal masses, and integrated management.

Core Tip: Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare, aggressive neuroendocrine skin cancer often misdiagnosed owing to its non-specific presentation. This case report details the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges of MCC in the nasal dorsum of a patient with diabetes and hypertension. Emphasizing multidisciplinary collaboration, it highlights the role of advanced imaging, histopathological analysis, and tailored treatment strategies. By sharing insights from a unique clinical scenario, this report adds to the growing body of literature on MCC and underscores the importance of early recognition and comprehensive care in managing atypical presentations of this malignancy.

- Citation: Abuharb AIA, Alzamil AF, Alqarni KS, Alsudays AM, Alqahtani SM, Alahmadi RM, Mutairy ASA, Alghamdi FR. Merkel cell carcinoma presenting as a nasal dorsum mass: A case report and literature review. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(24): 105244

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i24/105244.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i24.105244

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is an uncommon neuroendocrine carcinoma of the skin that predominantly affects sun-exposed areas in older and immunocompromised individuals. The incidence of MCC is low; however, an increase in cases has been observed, likely attributed to heightened awareness of the disease and improved diagnostic methods[1,2]. MCC incidence rises sharply with age; 0.1, 1.0, and 9.8 per 100000 person-years for ages 40–44, 60–64, and 85+, respectively. With the aging population, United States cases are projected to reach 2835 in 2020 and 3284 by 2025[3]. MCC has non-specific physical attributes and typically manifests as a red or pink lesion measuring less than 2 cm. MCC also typically presents intravascular invasion, an increased risk of local recurrence, and distant metastasis, resulting in a high death rate even after surgical excision and treatment[4,5].

In this case report, we comprehensively describe the management approach for nasal dorsum MCC in a patient with diabetes mellitus and hypertension. We emphasize the diagnostic challenges and therapeutic considerations necessitated in this unique clinical scenario. This report will contribute to the growing body of knowledge on MCC by providing unique insights into the management of a rare presentation involving the nasal dorsum, a site not commonly associated with MCC. The implications of this study extend beyond individual patient care, highlighting the importance of accurate diagnosis in atypical presentations, the utility of advanced imaging techniques such as PET-CT, and the role of a multidisciplinary approach in achieving optimal outcomes. Furthermore, it underscores the necessity of heightened awareness among clinicians for early detection, particularly in patients with significant comorbidities, to improve survival rates and reduce recurrence risks in MCC cases.

A 65-year-old woman, with a 10-year history of diabetes mellitus and hypertension and no smoking history, presented with a rapidly enlarging mass in her nasal dorsum.

One year prior, the lesion had the appearance of a 1 cm × 1 cm pimple. The mass was erroneously diagnosed as a hemangioma based on early physical examination and imaging studies. However, significant growth over the following 2 months necessitated referral to our otorhinolaryngology clinic.

A 65-year-old woman with a 10-year history of diabetes mellitus and hypertension, with no history of smoking.

The patient did not mention any notable personal or family history besides the chronic conditions stated above.

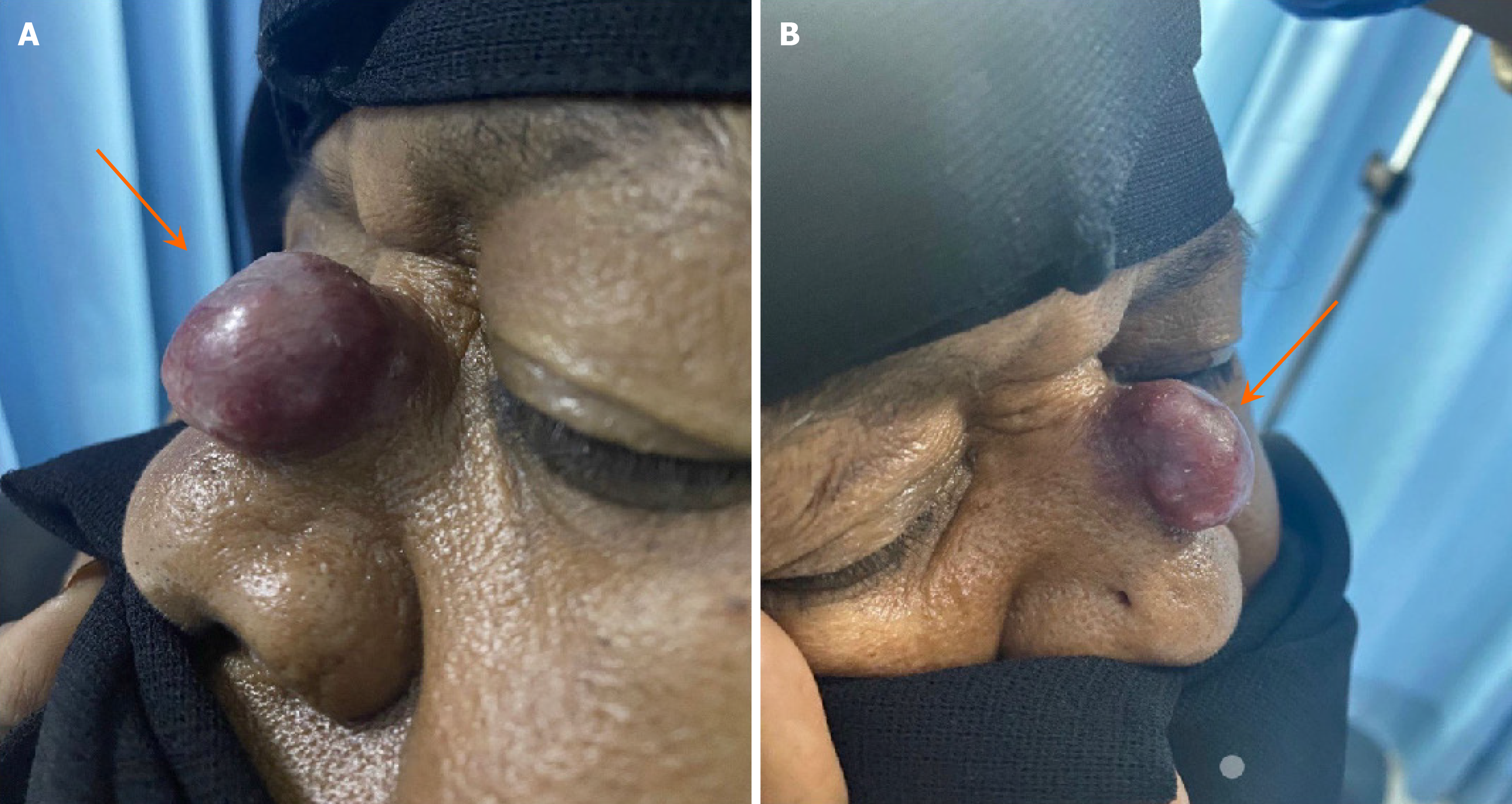

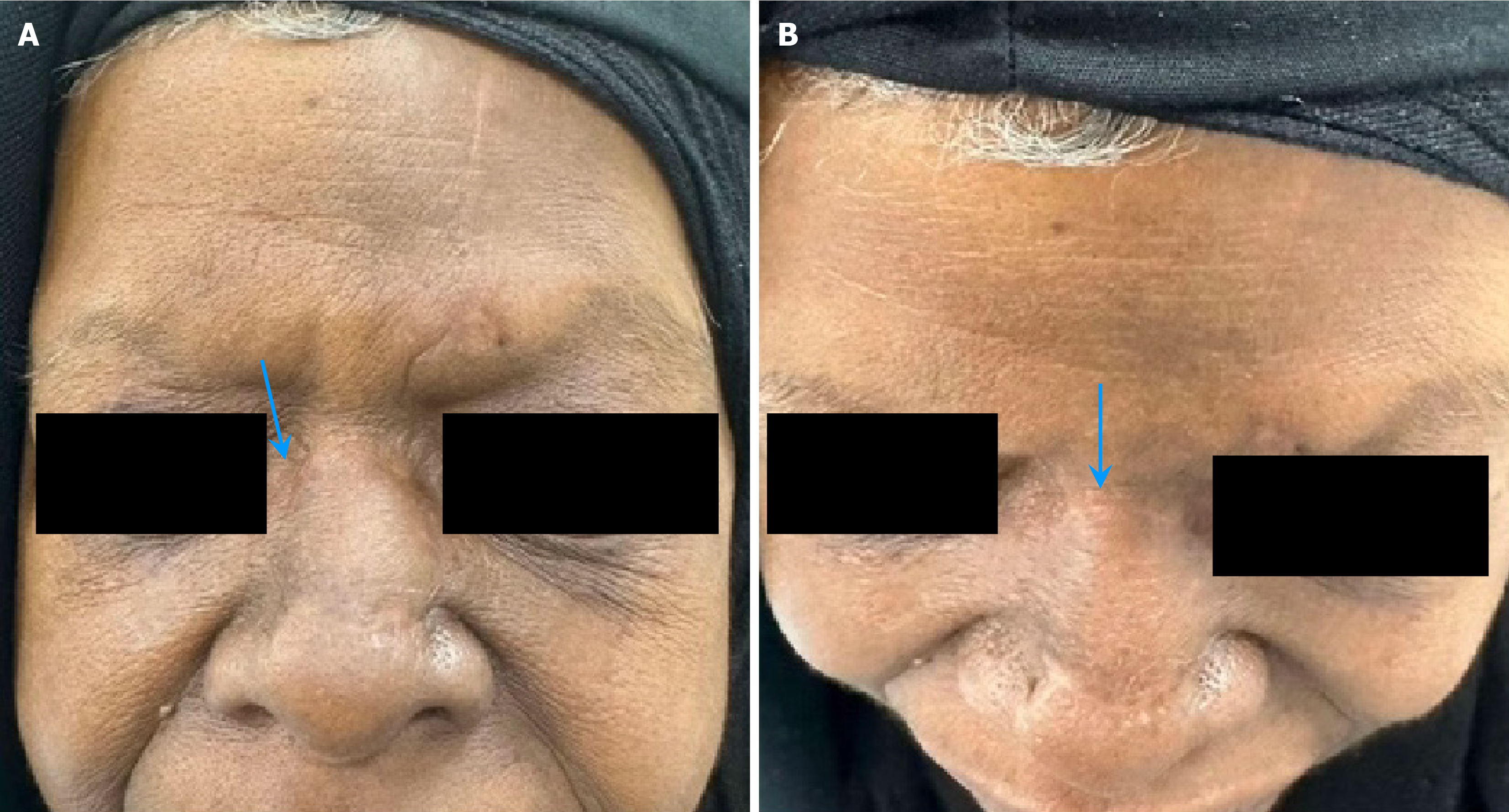

Upon initial presentation, we examined the head and neck, with particular attention to the nasal region. The mass on the nasal dorsum was noted as a large 3 cm × 2 cm pedunculated mass with a wide base over the nasal dorsum (middle 1/3), purple (reddish blue) in color. The remaining head and neck examinations were unremarkable, with no palpable neck lymphadenopathy. Additionally, endoscopic examination revealed no abnormalities in the nasal cavity, and neurological examination identified intact function of all the cranial nerves (CN I–XII) (Figure 1).

The biopsy of the suspected lymph nodes confirmed the diagnosis of MCC, characterized by neoplastic cells positive for pan-CK, CK20, CK (LMW), CK (AE3), Cam 5.2 (dot-like perinuclear), synaptophysin, and focal chromogranin. The cells tested negative for CK7, CK5/6, TTF1, desmin, actin, S100, CD45, CD3, CD5, and CD20. The Ki-67 proliferative index was approximately 70%, indicating a high-grade neuroendocrine tumor. The primary tumor, measuring 2.8 cm in greatest dimension, was located on the nasal dorsum and affected the epidermis, dermis, and skeletal muscle fibers. Histologically, the tumor exhibited an infiltrative growth pattern with lymphovascular invasion and brisk tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. No second malignancy was identified. The pathological staging (AJCC 8th edition) was pT2 Nx. These microscopic and immunohistochemical findings indicate MCC.

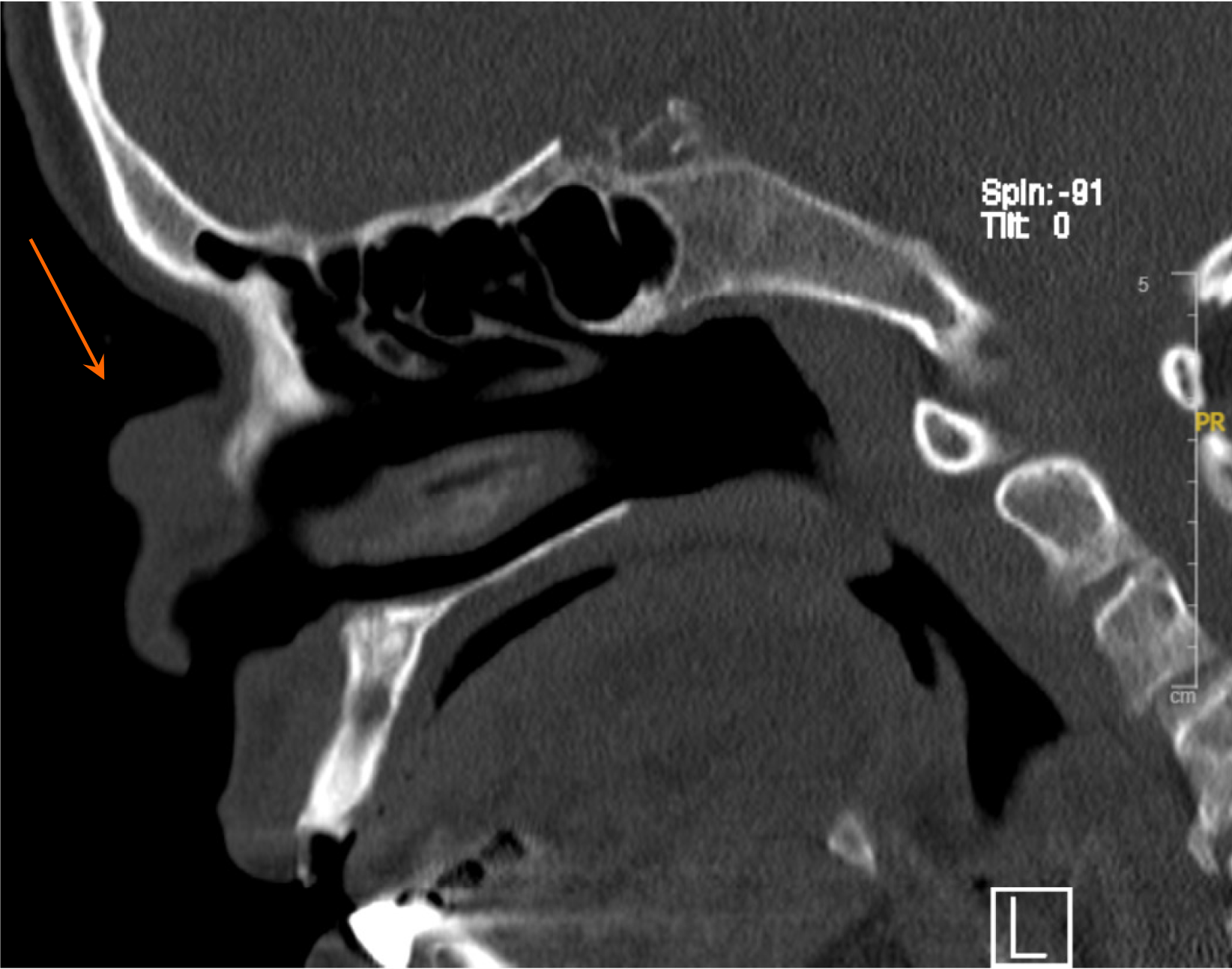

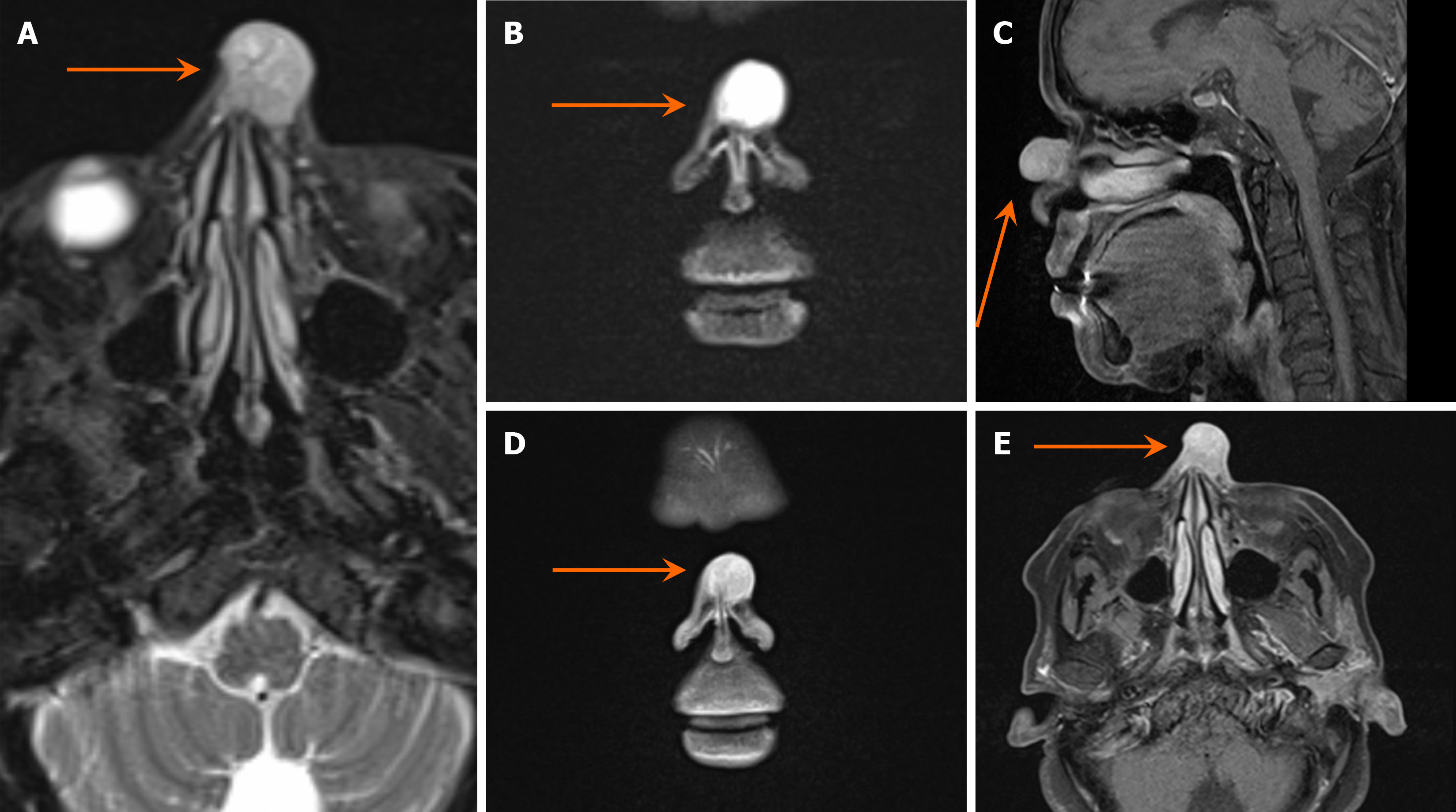

Doppler ultrasound imaging revealed a superficial heterogeneous soft tissue mass with a hypoechoic appearance and prominent internal vascularity with arterial flow. Subsequently, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the paranasal sinuses was performed. The MRI depicted a midline cutaneous pedunculated nasal mass that measured 1.8 cm × 1.9 cm × 1.9 cm and featured heterogeneous signals that were predominantly high on T2-weighted images and isointense on T1, along with homogeneous contrast enhancement. The mass was associated with an underlying bone defect but had no intracranial extension or other significant lesions, except for mild inflammatory changes in the left maxillary sinus. This raised the suspicion of either a primary skin lesion or hemangioma (Figures 2 and 3). The preliminary diagnosis was hemangioma owing to the initial clinical appearance and imaging characteristics of the lesion. The mass presented as a reddish blue pedunculated growth, a description commonly associated with vascular lesions such as hemangiomas. Additionally, Doppler ultrasound revealed a superficial heterogeneous soft tissue mass with prominent internal vascularity and arterial flow, findings typical of hemangiomas. Furthermore, the MRI depicted a well-defined, midline cutaneous lesion with no intracranial extension or significantly associated abnormalities, supporting the assumption of a benign vascular lesion. These features, combined with the patient’s unremarkable head and neck examination, led to the initial diagnosis of hemangioma.

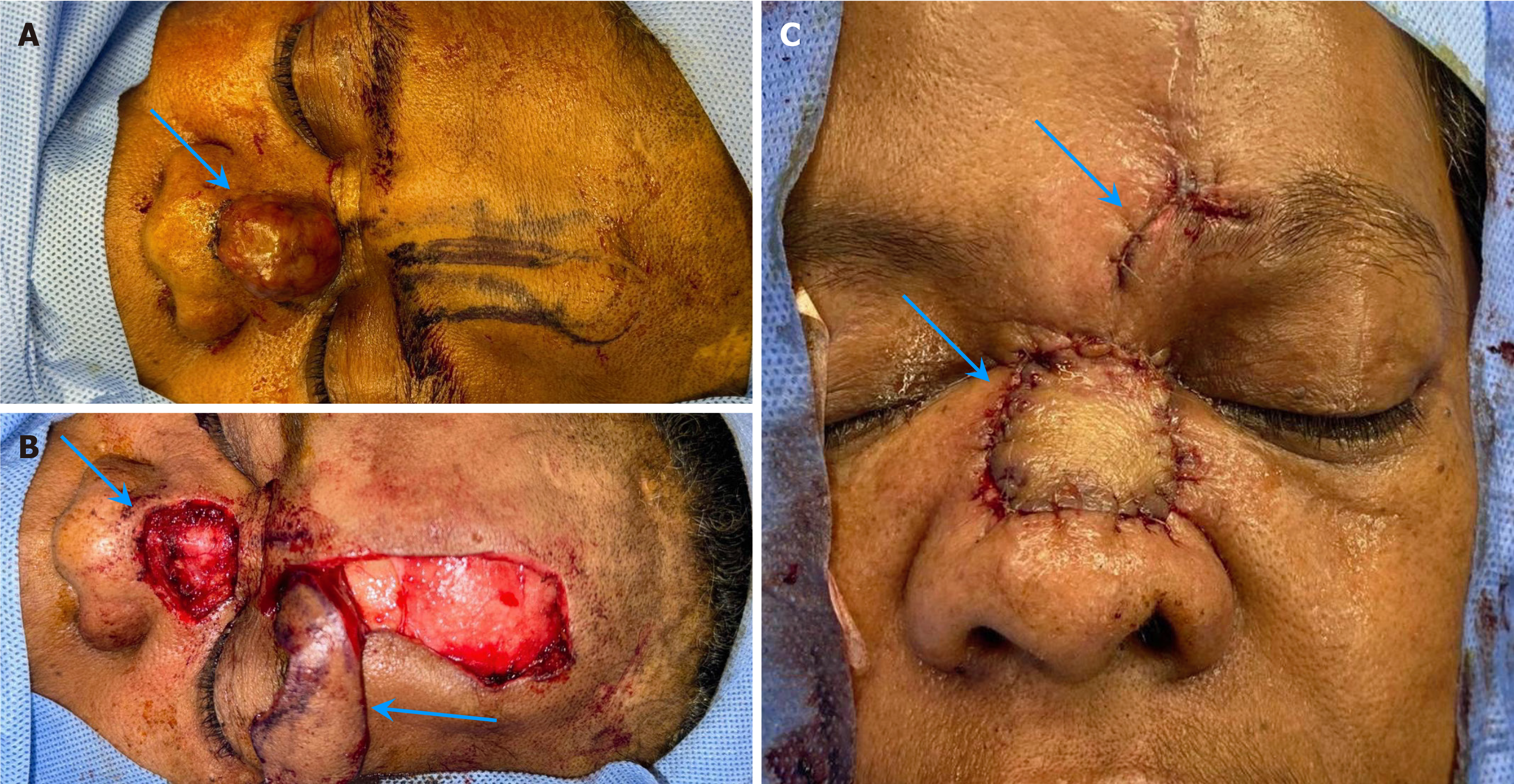

Following the initial surgical intervention to remove the mass, which involved a wide local excision, the defect was repaired using a paramedian forehead flap. Unfortunately, the histopathological examination revealed MCC with positive margins (Figure 4). Owing to this concerning finding, the patient was referred to a tumor board for further discussion and management planning.

Following the patient’s referral to the tumor board and a review of the findings, a multidisciplinary decision was made to proceed with a whole-body positron emission tomography (PET)–CT scan. The head and neck PET-CT scan revealed intensely hypermetabolic upper cervical lymphadenopathy, with specific findings that included a right level 1B lymph node measuring 1.8 cm × 2.8 cm, left level 2A lymph node measuring 0.9 cm × 1.6 cm, and left level 2B lymph node measuring 0.9 cm in diameter.

Biopsy of the suspected lymph nodes confirmed the diagnosis of MCC, characterized by neoplastic cells positive for pan-CK, CK20, CK (LMW), CK (AE3), Cam 5.2 (dot-like perinuclear), synaptophysin, and focal chromogranin. The cells were negative for CK7, CK5/6, TTF1, desmin, actin, S100, CD45, CD3, CD5, and CD20. The Ki-67 proliferative index was approximately 70%, supporting a high-grade neuroendocrine tumor. The primary tumor was located on the nasal dorsum, measuring 2.8 cm in greatest dimension, and involving the epidermis, dermis, and skeletal muscle fibers. Histologically, the tumor showed an infiltrative growth pattern, with lymphovascular invasion and brisk tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. No second malignancy was identified. Pathological staging (AJCC 8th edition) was pT2 Nx. These microscopic and immunohistochemical findings are consistent with MCC. CT scans of the abdomen, pelvis, and chest revealed no evidence of metastatic disease. Subsequently, we decided to perform bilateral neck dissection with adjuvant therapy to address the locoregional metastasis identified on PET-CT.

The patient underwent modified radical neck dissection from level 1 to 5 lymph nodes bilaterally. The preoperative staging indicated T2N2M0 disease. The pathology report revealed metastatic carcinoma in a total of seven lymph nodes across the right and left levels 1B and left levels 2, 3, and 4 (2/2 in right 1 B, 1/1 in left 1 B, 2/6 in left 2, 3, and 4). A subsequent PET-CT scan showed no residual activity at the primary site or previously dissected submandibular lymph nodes. However, it revealed an increase in the size and metabolic activity of the previously noted bilateral level 2 and 3 cervical lymph nodes. The patient was considered a high-risk patient due to the previously mentioned TNM staging, lymph node metastasis, positive margins from the first excision, and positive lymphovasculer invasion.

Based on these findings, the tumor board established this patient as high risk and opted for radiation therapy as the initial treatment, with surgery reserved as a salvage option if the patient did not respond to radiation.

The patient completed the treatment course including 30 sessions of radiation therapy and showed complete response to the treatment with no clinical evidence of residual disease after six months of follow-up (Figure 5).

MCC primarily affects the head and neck, and frequently spreads to lymph nodes. Its risk factors include sun exposure, immunosuppression, and older age. Early detection improves outcomes, aided by dermoscopy and imaging (ultrasound, MRI, and PET) to assess tumor size and metastasis[6-9].

MCC management focuses on surgical excision with clear margins and sentinel lymph node biopsy to guide treatment. Radiotherapy reduces recurrence risk, while immunotherapy shows promise for advanced cases. A multimodal approach may be needed for high-risk patients. Accurate diagnosis is crucial, as MCC mimics other skin cancers, requiring biopsy and pathology to ensure appropriate treatment[10-12].

In this case, a 65-year-old woman with comorbidities (hypertension and diabetes mellitus) presented with a nasal MCC requiring a paramedian forehead nasal flap and supraomohyoid neck dissection, followed by adjuvant radiotherapy. Despite lymph node involvement in right level 1B and left levels 2B and 2A, no post-surgical complications were observed, and the patient responded well to treatment. This highlights the importance of a multidisciplinary approach and careful tailoring to manage comorbid conditions.

Comparatively, a case in 2022 (56-year-old man) involved a bilateral supraomohyoid neck dissection and adjuvant radiotherapy, with no lymph node involvement or post-surgical complications[13]. Both cases demonstrate effective management of MCC with a surgical and radiotherapeutic approach, but our case is notable for its higher lymph node involvement, likely due to delayed detection caused by the atypical presentation.

A 2018 (83-year-old woman) and a 1987 (61-year-old man) case involved tumor excision alone, with no post-surgical complications or lymph node involvement in the 2018 case, but regional lymph node involvement in the 1987 case[14-16]. This suggests that tumor excision alone may be sufficient in cases with low risk, but lymph node involvement may warrant additional treatment strategies as in our case[14-16].

A 2010 case (63-year-old woman) illustrated a more aggressive disease course with cervical and supracervical lymph node involvement. The management involved tumor excision, bilateral neck dissection, and adjuvant chemotherapy (etoposide) and radiotherapy, but the patient had significant post-surgical complications, including acute necrotic pancreatitis and chronic cholecystitis[16]. In contrast, we avoided chemotherapy due to the patient’s comorbid conditions and demonstrated favorable outcomes, highlighting the need for individualized treatment based on patient factors[16].

Similarly, a 2000 case (79-year-old man) underwent a paramedian forehead nasal flap and neck dissection with adjuvant radiotherapy, resulting in no post-surgical complications[17]. However, lymph node involvement was limited to a single sentinel node in the right neck, compared to the more extensive nodal involvement in our case. This difference underscores the aggressive potential of MCC in some patients, even with similar management[17].

Lastly, a 1995 case (78-year-old woman) involved comorbid chronic lymphatic leukemia and asthma, requiring wide tumor excision and skin grafting along with adjuvant radiotherapy. This case was further complicated by lymph node involvement, including enlarged nodes behind the left jaw and neck. Unlike our case, where the disease was confined to cervical lymph nodes, this case shows the role of systemic comorbidities in influencing disease progression[18].

In summary, our case aligns with cases of the typical demographic of MCC patients, as most are older adults, often in their 60s–80s. Unlike cases with minimal nodal involvement or no comorbidities[13,17], ours involved significant comorbidities (hypertension and diabetes) and extensive lymph node metastases, necessitating a more aggressive approach with surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy, while avoiding chemotherapy. Despite these factors, our case, like most others, had no post-surgical complications, in contrast to the 2010 case[16], which demonstrated severe morbidity, further highlighting the importance of individualized, multidisciplinary management tailored to clinical and pathological features (Table 1).

| Ref. | Age (years) | Sex | Comorbid condition | Management | Post-surgical complications | Lymph nodes involvement | Follow up duration/ outcome |

| Swanson et al[12] | 56 | Male | None | Bilateral supraomohyoid neck dissection with adjuvant radiotherapy | None | None | At 30-month follow-up, magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography showed no locoregional recurrence |

| De Sousa Machado et al[13] | 83 | Female | None | Tumor excision | None | None | This patient had surgery only and remained disease-free for over 10 years |

| Nagase et al[14] | 63 | Female | None | Tumor excision + bilateral neck dissection + adjuvant chemotherapy(etoposide) and radiotherapy | Acute necrotic pancreatitis and chronic cholecystitis | Cervical and supracervical | The patient was last hospitalized in September 2008 for pneumonia and died 17 months after Merkel cell carcinoma diagnosis due to rapid health decline |

| Rocamora et al[15] | 79 | Male | None | Paramedian forehead nasal flap and right supraomohyoid neck dissection+ adjuvant radiotherapy | None | Right neck level 1 sentinel node | No evidence of disease at 16 months follow-up postoperatively |

| Gessner et al[16] | 61 | Male | History of basal cell carcinoma | Tumor excision | None | Regional lymph nodes involvement | At 18 months, the patient was well with no signs of local or systemic disease |

| Zeitouni et al[17] | 78 | Female | Well controlled chronic lymphatic leukemia and asthma | Wide excision of the tumor involving the nasal tip, dorsum of the left side of the nose, and adjacent cheek, with clearance up to the periosteum of the maxilla + skin grafting was performed after the excision with adjuvant radiotherapy | Left parotic mass | Enlarged lymph nodes behind the left jaw angle operation, enlarged left neck lymph node | Currently under follow-up with no clinical evidence of residual disease |

| This case | 65 | Female | Hypertension, diabetes mellitus | Paramedian forehead nasal flap + modified radical neck dissection + adjuvant radiotherapy of 30 sessions | None | Right level 1B, left level 2B and 2A | No clinical evidence of residual disease after 6 months follow-up |

MCC, particularly in rare locations such as the nasal dorsum, presents significant challenges for diagnosis and management. This case report highlights the critical need to suspect atypical presentations, importance of a comprehensive diagnostic approach, and role of a multidisciplinary team in managing such complex patients, especially those with significant comorbidities. Early detection is crucial for improving outcomes, yet diagnosing MCC in uncommon sites remains difficult due to its non-specific appearance. Further research and case reports are essential to develop standardized guidelines for managing MCC in unusual locations.

We express our sincere gratitude to the patient and their family for their cooperation and willingness to allow their case to contribute to medical knowledge. We also thank Prince Sultan Military Medical City for their support and aid in managing this case and providing the necessary resources for this report. We have ensured that all information has been anonymized, and confidentiality has been maintained to protect the patient's identity, and obtained written informed patient consent for the publication of figures related to the patients’ condition in which the patient may be identifiable.

| 1. | Brady M, Spiker AM. Merkel Cell Carcinoma of the Skin. 2023 Jul 17. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2025. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Siqueira SOM, Campos-do-Carmo G, Dos Santos ALS, Martins C, de Melo AC. Merkel cell carcinoma: epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis and treatment of a rare disease. An Bras Dermatol. 2023;98:277-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Paulson KG, Park SY, Vandeven NA, Lachance K, Thomas H, Chapuis AG, Harms KL, Thompson JA, Bhatia S, Stang A, Nghiem P. Merkel cell carcinoma: Current US incidence and projected increases based on changing demographics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:457-463.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 358] [Article Influence: 44.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Becker JC, Stang A, DeCaprio JA, Cerroni L, Lebbé C, Veness M, Nghiem P. Merkel cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 390] [Article Influence: 48.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Albores-Saavedra J, Batich K, Chable-Montero F, Sagy N, Schwartz AM, Henson DE. Merkel cell carcinoma demographics, morphology, and survival based on 3870 cases: a population based study. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:20-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 373] [Cited by in RCA: 378] [Article Influence: 23.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bell D. Sinonasal Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Current Challenges and Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment, with a Focus on Olfactory Neuroblastoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2018;12:22-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | American Cancer Society. Merkel cell skin Cancer - Merkel cell carcinoma, n.d. 20/11/2024. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/merkel-cell-skin-cancer.html. |

| 8. | American Cancer Society. Merkel cell carcinoma treatment (PDQ®). Available from: https://www.cancer.gov/types/skin/hp/merkel-cell-treatment-pdq. |

| 9. | Zaggana E, Konstantinou MP, Krasagakis GH, de Bree E, Kalpakis K, Mavroudis D, Krasagakis K. Merkel Cell Carcinoma-Update on Diagnosis, Management and Future Perspectives. Cancers (Basel). 2022;15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | American Cancer Society. Treating Merkel cell carcinoma based on the extent of the cancer. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/merkel-cell-skin-cancer/treating/common-treatments-by-extent.html. |

| 11. | Andea A, Mefcalf J, Satter E, Adsay V. Metastatic Basal Cell Carcinoma with Neuroendocrine Differentiation or Merkel Cell Carcinoma? J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:73-73. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Swanson MS, Sinha UK. Diagnosis and management of merkel cell carcinoma of the head and neck: current trends and controversies. Cancers (Basel). 2014;6:1256-1266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | De Sousa Machado A, Silva A, Brandao J, Meireles L. Merkel Cell Carcinoma: An Otolaryngological Point of View of An Unusual Sinonasal Mass. Cureus. 2022;14:e31676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Nagase K, Inoue T, Koba S, Narisawa Y. Case of probable spontaneous regression of Merkel cell carcinoma combined with squamous cell carcinoma without surgical intervention. J Dermatol. 2018;45:858-861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Rocamora A, Badía N, Vives R, Carrillo R, Ulloa J, Ledo A. Epidermotropic primary neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma of the skin with Pautrier-like microabscesses. Report of three cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:1163-1168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gessner K, Wichmann G, Boehm A, Reiche A, Bertolini J, Brus J, Sterker I, Dietzsch S, Dietz A. Therapeutic options for treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;268:443-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zeitouni NC, Cheney RT, Delacure MD. Lymphoscintigraphy, sentinel lymph node biopsy, and Mohs micrographic surgery in the treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:12-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gupta RK, Teague CA. Aspiration cytodiagnosis of metastatic Merkel-cell carcinoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 1995;12:259-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |