Published online Jun 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i17.4159

Peer-review started: March 22, 2023

First decision: April 11, 2023

Accepted: May 9, 2023

Article in press: May 9, 2023

Published online: June 16, 2023

Processing time: 81 Days and 22.5 Hours

Gallstone ileus is a rare complication of gallstone disease in which a stone enters the enteric lumen and causes mechanical obstruction usually by bilioenteric fistula. Gallstone ileus accounts for 25% of all bowel obstructions among the population > 65 years of age. Despite medical advances over the last decades, gallstone ileus is still associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality.

An 89-year-old man with a history of gallstones was admitted to the Gastroenterology Department of our hospital, complaining of vomiting and cessation of bowel movements and flatus. Abdominal computed tomography showed cholecystoduodenal fistula and upper jejunum obstruction due to gallstones, pneumatosis in the gallbladder, and pneumobilia indicating Rigler’s triad. Considering the high risk of surgical management, we performed propulsive enteroscopy and laser lithotripsy twice to relieve the bowel occlusion. However, the intestinal obstruction was not relieved by the less invasive procedure. Then, the patient was transferred to the Department of Biliary-pancreatic Surgery. The patient underwent the one-stage procedure including laparoscopic duodenoplasty (fistula closure), cholecystectomy, enterolithotomy, and repair. After surgery, the patient presented with complications of acute renal failure, postoperative leak, acute diffuse peritonitis, septicopyemia, septic shock, and multiple organ failure, and finally died.

Early surgical intervention is the mainstay of treatment for gallstone ileus. For elderly patients with significant comorbidities, enterolithotomy alone is advised.

Core Tip: Gallstone ileus is a rare complication of gallstone disease that is common in elderly patients, with high mortality. In this case of gallstone ileus, abdominal imaging showed classical Rigler’s triad including ectopic gallstone, intestinal obstruction, and pneumobilia. We performed propulsive enteroscopy and laser lithotripsy twice but failed to remove the stone. Finally, the patient underwent the one-stage procedure including laparoscopic duodenoplasty (fistula closure), cholecystectomy, and enterolithotomy. However, the patient presented with several complications including acute renal failure and finally died. Early surgical intervention is the main treatment for gallstone ileus. For elderly patients with significant comorbidities, enterolithotomy alone is advised.

- Citation: Fan WJ, Liu M, Feng XX. Endoscopic and surgical treatment of jejunal gallstone ileus caused by cholecystoduodenal fistula: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(17): 4159-4167

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i17/4159.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i17.4159

Gallstone disease represents a major public health problem. There are several complications of gallstones, including the Mirizzi syndrome, gallstone ileus, and gallstone pancreatitis[1]. Gallstone ileus is a rare complication of gallstone disease complicating about 0.5% of gallstone disease[2] in which a stone enters the enteric lumen and causes mechanical obstruction. Gallstone ileus accounts for 1%-4% of all causes of mechanical bowel obstruction but accounts for 25% of all bowel obstructions in the population > 65 years of age[3], indicating that it mainly affects the elderly population. The mortality of gallstone ileus is high, which ranges in the literature from 7% to 30% (average 18%)[4]. Herein, we present a patient with jejunal gallstone ileus caused by cholecystoduodenal fistula who was treated by endoscopy and surgery.

An 89-year-old man presented to the Gastroenterology Department of our hospital complaining of vomiting for 4 d.

The patient developed vomiting 4 d ago after eating milk and fruits, which appeared as projectile vomiting with epigastric distension. He did not have obvious abdominal pain. He reported having had neither bowel movements nor flatus.

The patient had a history of gallstones for 10 years with intermittent right upper quadrant pain that was treated conservatively. He also had a history of hypertension and diabetes. About 50 years ago, he had a history of pulmonary tuberculosis and schistosomiasis.

The patient had a history of moderate drinking but no smoking. He denied a history of allergies and had an unremarkable family history.

The patient’s temperature was 36.2 °C, heart rate was 77 beats per min, respiratory rate was 20 breaths per min, and blood pressure was 137/74 mmHg. Abdominal examination showed slight abdominal tenderness in the epigastric abdomen without rebound tenderness. Abdominal auscultation showed hyperactive bowel sounds in the right abdomen. Lung and heart examinations were normal.

After admission, blood analysis showed normal findings for routine blood examination, liver and renal function, coagulation function, troponin, and procalcitonin. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein was increased (26.1 mg/L; normal range: < 1 mg/L).

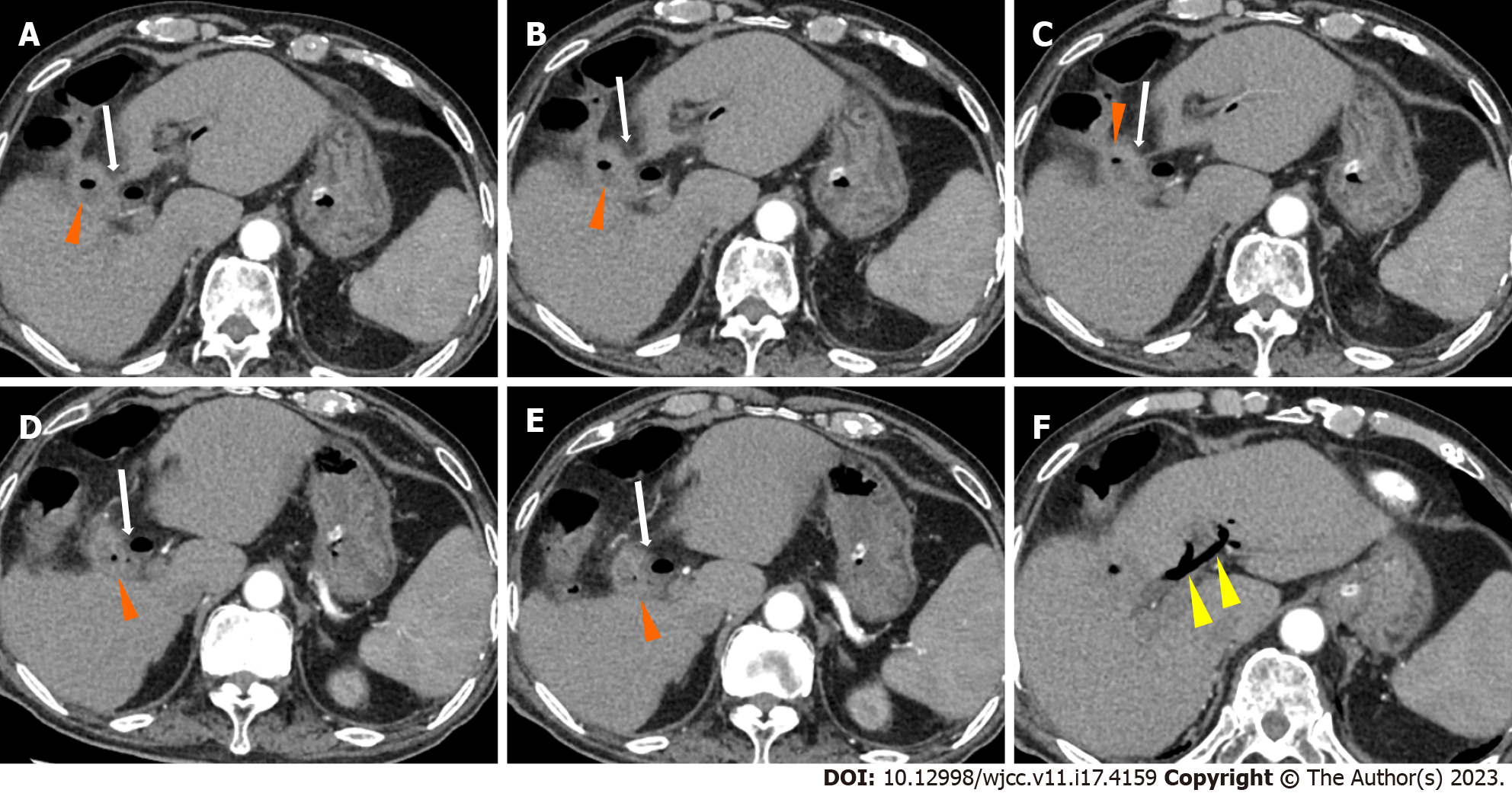

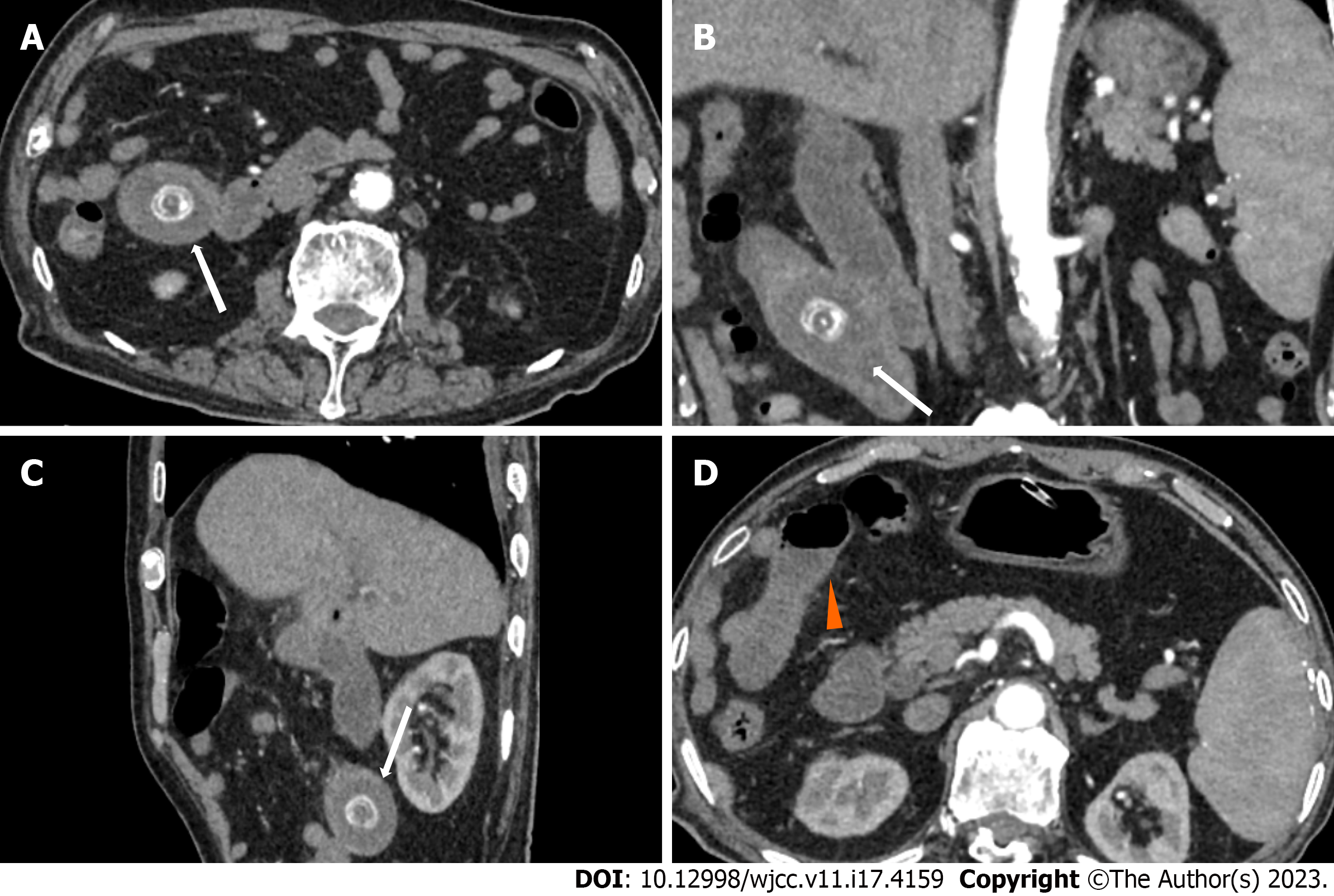

Abdominal contrast computed tomography (CT) showed a normal shape of the liver with dilatation of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic ducts. Pneumatosis was observed in the gallbladder, and the gallbladder communicated with the duodenal bulb (Figures 1 and 2). A stone was shown in the upper jejunum with proximal intestinal effusion and dilatation (Figure 3). CT showed cholecystoduodenal fistula and upper jejunum obstruction due to a gallstone. Cholecystitis and pneumobilia (Figure 1) were also observed. This combination of radiologic findings of an ectopic gallstone, small bowel obstruction, and pneumobilia is known as Rigler’s triad and aroused concern about gallstone ileus. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography showed short T2 signal as long as 25 mm in the upper jejunum with proximal intestinal dilatation and cholecystoduodenal fistula (Figure 4).

Jejunal gallstone ileus, cholecystoduodenal fistula, cholecystitis, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, and diabetes; postoperative leak, acute diffuse peritonitis, septicopyemia, septic shock, multiple organ failure, myocardial damage, acute renal failure, coagulation disorder and pulmonary infection.

After admission, ceftriaxone sodium and sulbactam sodium (3 g bid) were used as anti-infective treatments. Octreotide acetate (0.3 mg Q12H) was given intravenously to reduce intestinal secretion. Esomeprazole (40 mg QD) was used to reduce gastric acid secretion. Also, a nasogastric tube was inserted and gastrointestinal decompression was used for fluid drainage. Other nutrition support treatments were given, including amino acid and lipid emulsion. Gastrointestinal surgeon consultation determined that the patient had no indication for emergency surgery.

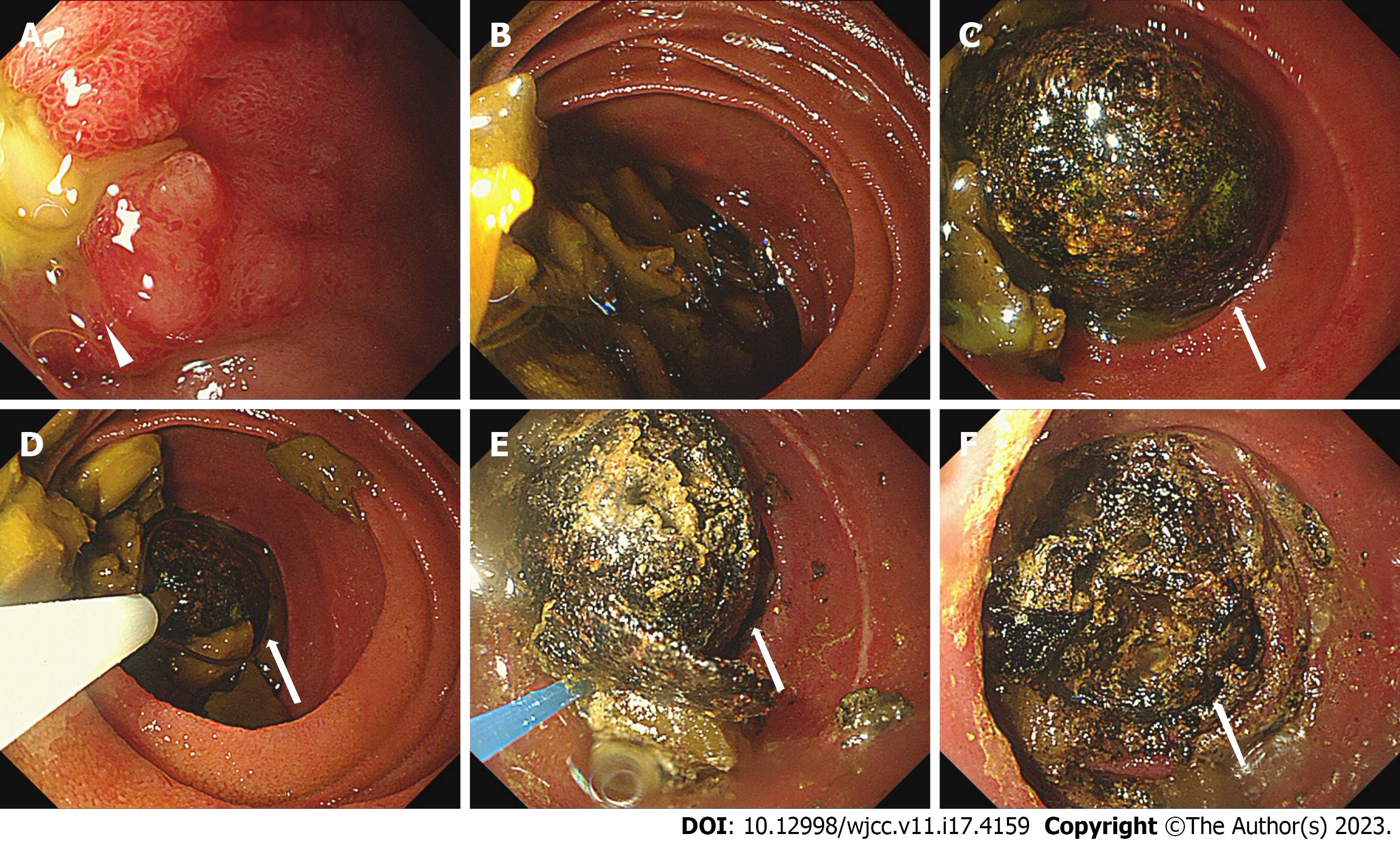

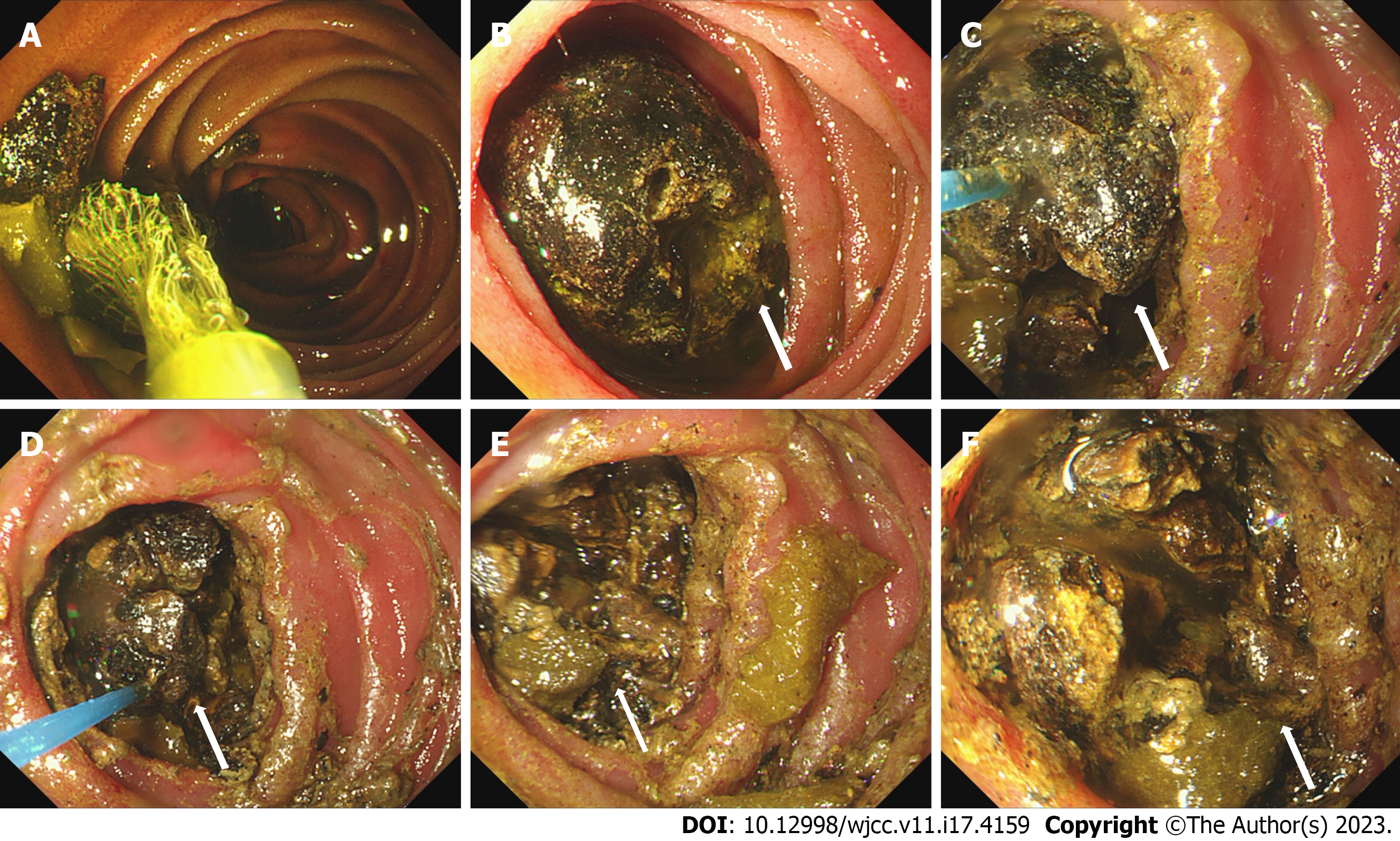

We performed propulsive enteroscopy and found a deep ulcer in the duodenal bulb close to the pylorus with yellow purulent secretion on the surface and mucosal edema (Figure 5). We could see a stone incarceration in the upper jejunum 1.4 m from the incisor (Figure 5). Food residue was abundant proximal to the gallstone, and we used a basket and snare to remove the food residue (Figure 5). We failed to take out the stone with a basket, snare, or titanium clip. Then, we performed laser lithotripsy and injected sodium bicarbonate on the stone (Figure 5). Two days later, we performed propulsive enteroscopy for a second time and found that the stone was smaller than before. We performed laser lithotripsy and injected sodium bicarbonate again (Figure 6).

Four days after the second propulsive enteroscopy, the patient still did not have passage of gas by the anus, and gastrointestinal decompression drainage yielded 800-1000 mL per day. The patient was transferred to the Department of Biliary-pancreatic Surgery. Eight days after transfer, the patient underwent laparoscopic duodenoplasty (fistula closure), cholecystectomy, enterolithotomy, and repair. Intraoperative exploration showed severe inflammation and edema around the gallbladder, cholecystoduodenal fistula formation, and jejunal gallstone ileus. The gallbladder was removed, a cauliflower drainage tube was placed around the duodenal fistula, and purse-string suturing of the full layer was performed. Then, the jejunum was cut, the gallstone was removed, and the intestine wall was sutured. Drainage tubes in the foramen of Winslow and pelvic cavity were placed. Two days after the surgery, the patient presented with tachycardia (170 beats per min), routine blood tests revealed a normal white blood cell count (7.13 × 109 cells/L), mild anemia (hemoglobin of 117.0 g/L; normal range: 130.0-175.0 g/L), hypoproteinemia (32.5 g/L; normal range: 35.0-52.0 g/L), and elevated levels of urea (14.74 mmol/L; normal range: 1.7-8.3 mmol/L), creatinine (149 µmol/L; normal range: 59-104 µmol/L), and NT-proBNP (5458 pg/mL; normal range: < 486 pg/mL). Troponin was normal. Electrocardiograph showed atrial fibrillation. Cardiac ultrasound showed pulmonary arterial hypertension (44 mmHg), enlargement of the right heart, and tricuspid insufficiency. Deslanoside (0.2 mg, intravenous injection) and amiodarone hydrochloride (0.3 mg, intravenous pump) were given, and the patient returned to sinus rhythm. Two days after the surgery, the patient developed hypourocrinia and became anuric. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit.

Then, the patient presented with hyperpyrexia (39 °C) and disturbance of consciousness. Blood tests showed an increase of white blood cells (10.11 × 109 cells/L, neutrophilic granulocyte percentage 90.5%), coagulation abnormalities involving prothrombin time (57.9 s; normal range: 11.5-14.5 s) and international normalized ratio (6.02; normal range: 0.8-1.2), and elevated troponin (5476.8 pg/mL; normal range: ≤ 34.2 pg/mL), NT-proBNP (31194 pg/mL), and creatinine (347 µmol/L). Procalcitonin was elevated at 31.01 ng/mL (normal range: < 0.05 ng/mL). High-sensitivity C-reactive protein was increased at 220.0 mg/L. Drainage fluid culture was positive for Enterococcus faecium, which was sensitive to vancomycin, tigecycline, linezolid, and teicoplanin. Meropenem (1.0 g Q8H for 16 d), tigecycline (50 mg Q12H for 4 d), linezolid (0.6 g Q12H for 7 d), and teicoplanin (400 mg QD for 4 d) were applied as anti-infective treatments.

The patient was given continuous renal replacement therapy for four times. Intravenous plasma transfusion, coronary dilating drugs, and other supporting treatments were also given. The patient presented with abdominal tenderness and rebound tenderness, exudate around the drainage tube, and hypotension. Doctors replaced the abdominal drainage tube and used noradrenaline and pituitrin to maintain blood pressure. The patient manifested a decrease in platelet count after use of linezolid, and he received teicoplanin. After treatment, his urine volume gradually recovered, and vital signs were stable. Nineteen days after the surgery, blood tests showed a decrease of white blood cell count (2.48 × 109 cells/L), moderate anemia (hemoglobin of 61.0 g/L), and elevated levels of creatinine (225 µmol/L), troponin (44.7 pg/mL), NT-proBNP (3229 pg/mL), and procalcitonin (1.74 ng/mL). He was transferred to the Department of Biliary-pancreatic Surgery.

Cefoperzone sodium and tazobactam sodium (2.5 g bid) were given as anti-infective treatment. Twenty-three days after the surgery, the patient presented with lethargy and mouth breathing. Blood tests showed no obvious change. Five days later, the patient was in a coma, and the pupils were unresponsive to light. Abdominal CT showed postoperative changes of the gallbladder and partial intestine with exudative effusion around the operative region. Chest CT showed infection in the right lung. Head CT showed low density in the left basal ganglia region and bilateral anterior horns of lateral ventricles, indicating cerebral infarction.

On the next day, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit again and received anti-infective therapy and other supportive treatments including enteral nutrition, maintenance of electrolytes, and oxygen therapy. Five days later, the patient presented with a decrease in blood pressure and oxyhemoglobin saturation and finally died.

The term “gallstone ileus” was first coined by Bartolin in 1654 and referred to the mechanical intestinal obstruction caused by impaction of a gallstone that had migrated from the gallbladder toward the intestine[5]. Although gallstone ileus is a rare complication of gallstone disease, it is an important disease in elderly patients. Despite medical advances over the last decades, gallstone ileus is still associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality. The mortality rate of gallstone ileus decreased from about 70% at the beginning of the last century to approximately 15%-20%[6].

Obstructing gallstones generally migrate to the bowel via bilioenteric fistulas, the most common of which is a fistulous connection from the gallbladder to the duodenum (85% of cases)[3]. Pericholecystic inflammation after episodes of cholecystitis causes adhesions between the biliary and enteric systems. The pressure between the gallstones and the wall of the gallbladder leads to necrosis, erosion, and fistula formation. The impacted stones are usually greater than 2.0-2.5 cm in diameter. The presentation of gallstone ileus is often nonspecific, which contributes to the delay of diagnosis. The average time between symptom onset and presentation is 4-8 d[7], and physical examination may be nonspecific. CT scanning is widely accepted as the investigation of choice in bowel obstruction. Our patient manifested classic radiologic findings of Rigler’s triad on CT, including intestinal obstruction, aberrant gallstone in the intestine, and pneumobilia.

There is no consensus regarding therapeutic timing and surgical procedure for gallstone ileus. The main therapeutic goal is to relieve the bowel occlusion by removing the stone. Surgical management is generally required. Usually radiological indications for urgent surgical intervention include established or impending bowel perforation, signs of bowel ischemia, or evidence of significant intra-abdominal bleeding[4]. Considering surgical management in these elderly patients who may be frail with multiple comorbidities and a high risk of morbidity and mortality, we first chose endoscopic management, which is less invasive, for this patient. Endoscopic laser lithotripsy is a safe and feasible treatment option, and its benefit is precise targeting of the stone with minimal tissue injury[8]. Some doctors suggested that endoscopic management should always be considered before a surgical approach[9], but our attempts were unsuccessful due to the size and hardness of the impacted stone. Studies showed that only 10% of stones can be removed endoscopically[10].

The patient was finally transferred to the surgery treatment. Debate currently exists regarding the appropriate surgical strategy for emergency treatment of gallstone ileus. The most common surgeries include enterolithotomy alone or enterolithotomy with cholecystectomy and fistula repair (one-stage procedure). Our patient was an elderly patient comorbid with hypertension, diabetes, and atrial fibrillation, and he underwent the one-stage procedure by laparoscopy and presented several complications after surgery, including acute renal failure, myocardial damage, acute diffuse peritonitis, septicopyemia, septic shock, multiple organ failure, and finally death.

In the largest review of the literature, by Reisner et al[11], the one-stage procedure had a 16.9% mortality rate compared with 11.7% for enterolithotomy alone, and 80% of patients were treated by enterolithotomy alone. A logistic regression analysis also showed that the one-stage procedure had a significantly higher complication rate due to prolonged operative time, and this procedure should be reserved for selected groups of patients with cholecystitis and gangrenous gallbladder or residual gallstones at the time of operation[11]. For high-risk patients with multiple comorbidities or intra-abdominal inflammation or adhesions, enterolithotomy alone should be recommended[12]. The most common postoperative complications include acute renal failure, urinary tract infection, ileus, anastomotic leak, intra-abdominal abscess, enteric fistula, and wound infection[7].

The patient underwent surgery 18 d after admission due to conservative treatment, endoscopic therapy, and management of other comorbidities. The previous literature generally described a median delay between admission and surgical intervention of 2-37 d[4]. Early surgical intervention in the management of gallstone ileus is of key importance and is the mainstay of treatment, although conservative therapy can be indicated in elderly patients with rapid improvement of clinical symptoms. For our patient, his symptoms were not relieved after two endoscopic management attempts. We assume that the death was related to several surgical complications.

Gallstone ileus should be suspected in all cases admitted to the emergency service with acute intestinal obstruction with a history of cholelithiasis, especially in the elderly. Early surgical intervention is the mainstay of treatment for gallstone ileus. For elderly patients with significant comorbidities, enterolithotomy alone is advised. The one-stage procedure including cholecystectomy with fistula repair is independently associated with a higher prevalence of mortality and should be reserved for selected cases in otherwise healthy patients.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Oley MH, Indonesia; Takahashi K, Japan S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Zaliekas J, Munson JL. Complications of gallstones: the Mirizzi syndrome, gallstone ileus, gallstone pancreatitis, complications of "lost" gallstones. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88:1345-1368, x. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Farrell I, Turner P. A simple case of gallstone ileus? J Surg Case Rep. 2015;2015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ploneda-Valencia CF, Gallo-Morales M, Rinchon C, Navarro-Muñiz E, Bautista-López CA, de la Cerda-Trujillo LF, Rea-Azpeitia LA, López-Lizarraga CR. Gallstone ileus: An overview of the literature. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2017;82:248-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chang L, Chang M, Chang HM, Chang AI, Chang F. Clinical and radiological diagnosis of gallstone ileus: a mini review. Emerg Radiol. 2018;25:189-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yakan S, Engin O, Tekeli T, Calik B, Deneçli AG, Coker A, Harman M. Gallstone ileus as an unexpected complication of cholelithiasis: diagnostic difficulties and treatment. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2010;16:344-348. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Zuegel N, Hehl A, Lindemann F, Witte J. Advantages of one-stage repair in case of gallstone ileus. Hepatogastroenterology. 1997;44:59-62. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Dunphy L, Al-Shoek I. Gallstone ileus managed with enterolithotomy. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hendriks S, Verseveld MM, Boevé ER, Roomer R. Successful endoscopic treatment of a large impacted gallstone in the duodenum using laser lithotripsy, Bouveret's syndrome: A case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:2458-2463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Scuderi V, Adamo V, Naddeo M, Di Natale W, Boglione L, Cavalli S. Gallstone ileus: monocentric experience looking for the adequate approach. Updates Surg. 2018;70:503-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Baharith H, Khan K. Bouveret syndrome: when there are no options. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;29:17-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Reisner RM, Cohen JR. Gallstone ileus: a review of 1001 reported cases. Am Surg. 1994;60:441-446. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Doko M, Zovak M, Kopljar M, Glavan E, Ljubicic N, Hochstädter H. Comparison of surgical treatments of gallstone ileus: preliminary report. World J Surg. 2003;27:400-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |