Published online Mar 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i7.2322

Peer-review started: October 5, 2021

First decision: November 8, 2021

Revised: November 22, 2021

Accepted: January 19, 2022

Article in press: January 19, 2022

Published online: March 6, 2022

Processing time: 147 Days and 14.6 Hours

Gall bladder neuroendocrine tumors (GB-NETs) are rare, accounting for less than 0.5% of all NETs. They usually lack specific symptoms and are difficult to diagnose preoperatively. In most cases, GB-NETs are incidentally found after cholecystectomy for large polyps or cholelithiasis, causing acute or chronic cholecystitis. The coexistence of GB-NET and GB adenocarcinoma is very rare.

We report a case of synchronous but separate GB-NET and adenoma with high-grade dysplasia in a patient who had undergone surgery for a progressively growing GB polypoid lesion. To the best of our knowledge, simultaneous separation of NETs and cancer in the GB has not been reported.

Coexistent GB carcinoid tumor and adenocarcinoma is rare. A surveillance program is needed for these large GB polyps.

Core Tip: Gall bladder (GB) polyps are commonly found in routine abdominal ultrasound examination; however, GB carcinoid tumors are rare, especially with the coexistence of an adenocarcinoma component. Physicians should be aware of rapidly growing GB polyps; in those cases, imaging examinations such as contrast-enhanced computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are needed to elucidate the nature of these lesions.

- Citation: Hsiao TH, Wu CC, Tseng HH, Chen JH. Synchronous but separate neuroendocrine tumor and high-grade dysplasia/adenoma of the gall bladder: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(7): 2322-2329

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i7/2322.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i7.2322

A neuroendocrine tumor (NET) is a heterogeneous tumor, first reported and identified as a carcinoid tumor by Oberndorfer in 1907. NETs originate and spread from neuroendocrine cells and peptidergic neural crest Kulchitsky cells (silver-addicted cells)[1]. The first case of a primary carcinoid tumor of the gall bladder (GB) was reported by Joel in 1929[2]. Primary GB-NETs are very rare, and in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (commonly known as SEER) registry, only 278 cases were reported between 1973 and 2005. The incidence of GB-NETs is less than 0.74/100,000, and represents 0.5% of all NETs and approximately 2% of all GB malignancies[3]. They rarely occur because there are no neuroectodermal cells in the GB. Multipotent stem cells or neuroendocrine cells involved in intestinal or gastric metaplasia of the GB epithelium have recently been considered the origin of GB-NETs[4].

Here, we report a rare case of coexistent but separate NET and adenocarcinoma in situ in the GB.

A 61-year-old woman presented to the outpatient department with an abnormal magnetic resonance image (MRI) finding. She had undergone a medical checkup in another hospital, where she was advised to have a 1-2 cm segment of narrow lumen at the distal common bile duct (CBD) assessed further in another MRI study (Figure 1).

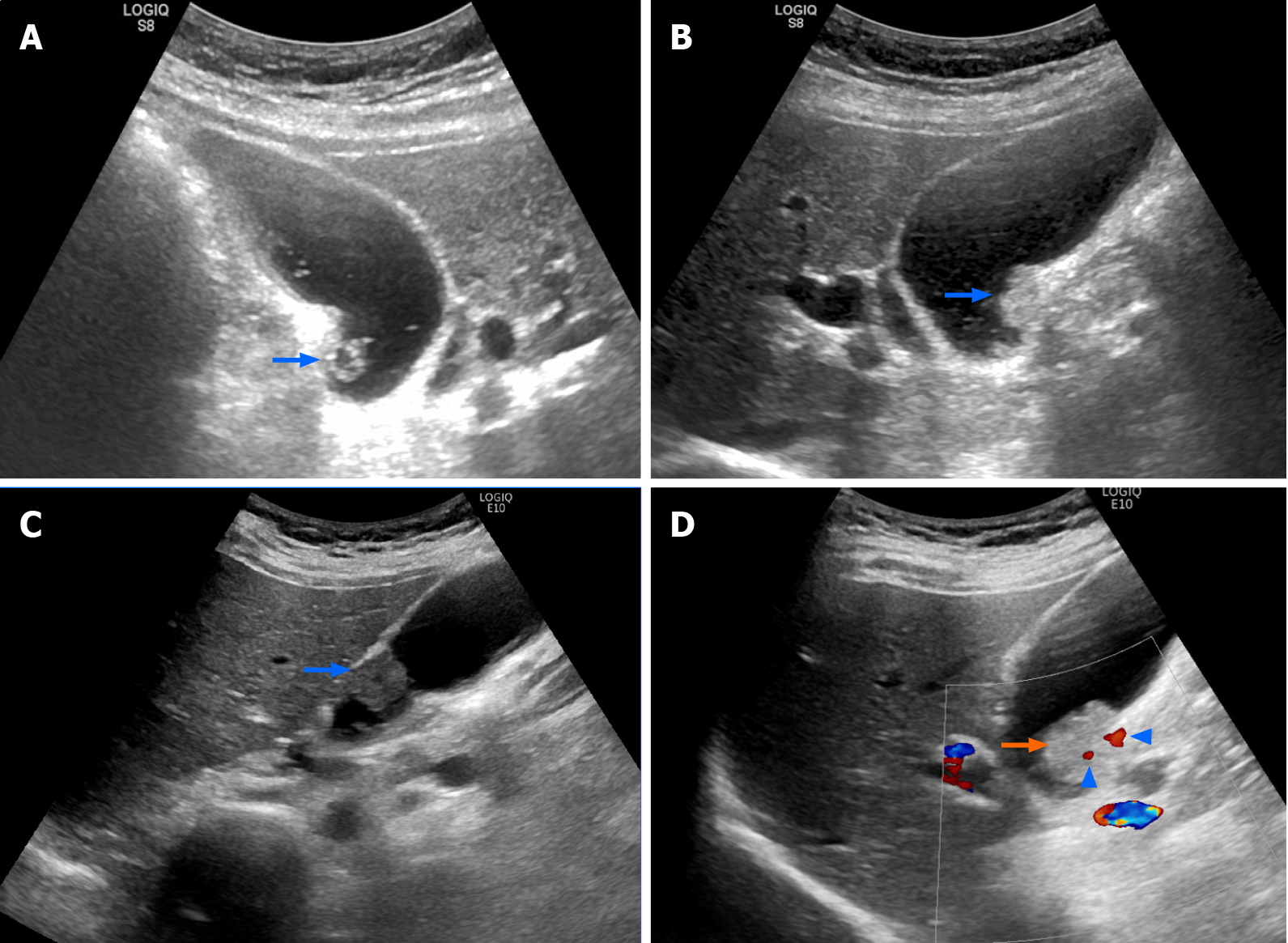

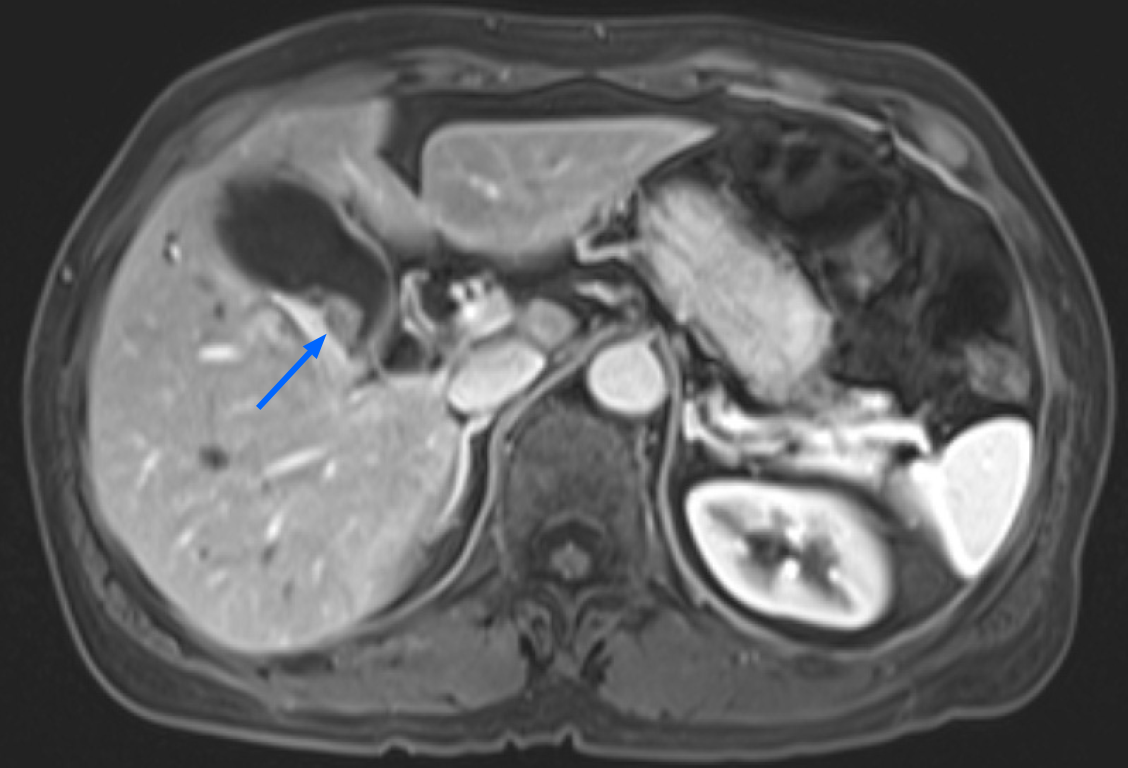

The patient denied having upper or right hypochondrial pain, and no jaundice was observed. She did not have fever or chills. Immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) levels were slightly elevated (246 mg/dL; normal range: < 200 mg/dL), and initial abdominal ultrasound (US) showed a mildly thickened distal CBD wall and an approximately 1 cm polypoid lesion in the GB (Figure 2A); therefore, IgG4-related cholangitis was suspected. Because the patient had no symptoms, she underwent regular abdominal US exams and measurement of blood IgG4 Levels at 6- to 12-mo intervals. However, the 1-year follow-up abdominal US showed that the GB polyp had grown (Figure 2B). After another 6 mo, the polyp was even larger and more hypoechoic in appearance (Figure 2C). After an additional 6 mo, abdominal US with Doppler revealed a 2 cm polypoid tumor (Figure 2D). Contrast MRI T2-weighted images revealed a 2-cm tumor near the neck of the GB (Figure 3). Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography showed that the morphology of the stricture segment of the distal CBD was not significantly changed. The patient subsequently underwent surgery.

The patient’s medical history was unremarkable.

The patient’s family history was unremarkable.

The patient’s physical examination was unremarkable. Her abdomen was soft, nontender and nondistended, with no palpable mass.

Laboratory examinations, including complete blood count and blood chemistry tests, revealed that white blood cell count (9051/mL) and serum levels of C-reactive protein (0.72 mg/dL), alkaline phosphatase (82 IU/L), gamma-glutamyl transferase (32 IU/L), aspartate transaminase (19 U/L), and alanine aminotransferase (28 U/L) were all within normal limits. Serological tests for hepatitis B antigen, anti-hepatitis C antibody, alpha-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 were negative. The IgG4 Level at follow-up was also within the normal range.

Two years later, abdominal US showed that the GB polypoid lesion had progressively increased to greater than 2 cm in size. Contrast MRI T2-weighted images (Figure 3) revealed a 2-cm tumor near the neck of the GB, and malignancy was highly suspected.

This consultation was not undertaken.

GB neuroendocrine tumor grade 2 and synchronous adenocarcinoma in situ.

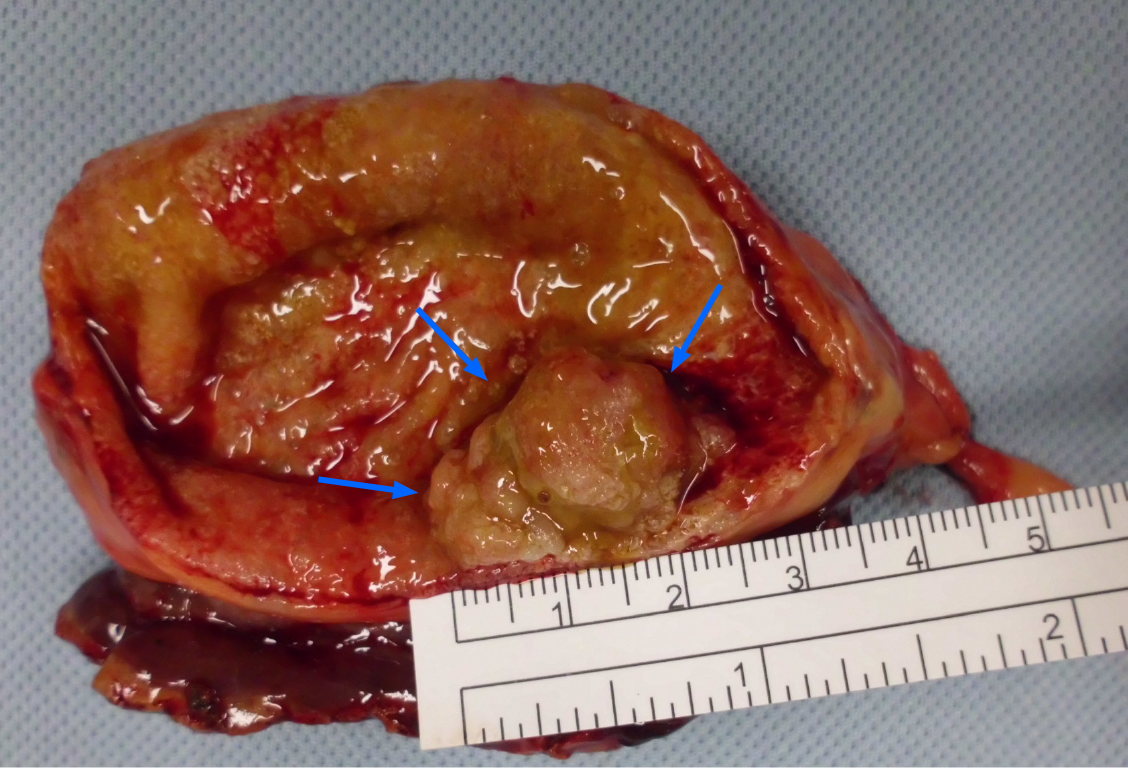

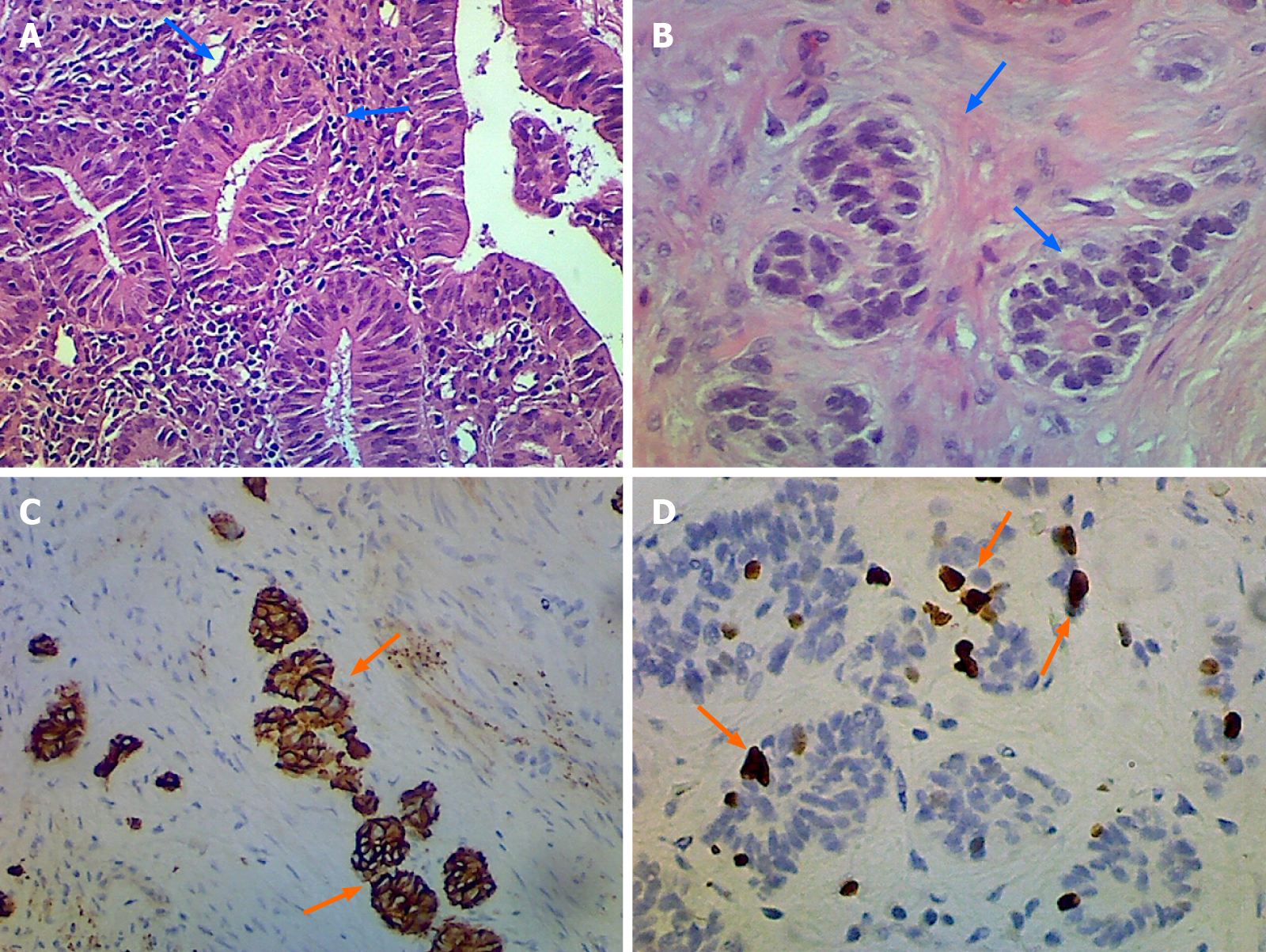

Radical laparoscopic cholecystectomy with partial liver tissue resection was subsequently performed (Figure 4). The intraoperative findings revealed no evidence of inflammation in the peri-GB area. The CBD looked negative for overall abnormalities but there were tumor features noted in its appearance. However, the outer surface of the GB in the liver bed showed no tumor invasion. The pathological findings are tubulo-villous adenoma with high-grade dysplasia and gall bladder neuroendocrine tumor grade 2 (Figure 5).

After a 1-year follow up, the patient’s postoperative course was uneventful, with no recurrence. Regarding the CBD stricture, we suggest that patients receive endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography brush cytology or endoscopic US with fine-needle aspiration biopsy.

More than 75% of GB cancers are adenocarcinomas, although many variant forms of GB carcinoma have been pathologically described[4]. GB-NETs are relatively rare histological tumors, accounting for 0.5% of all NET cases and only 2.1% of GB cancer cases[3]. Preoperative diagnosis of GB-NETs is difficult as patients tend to have no specific symptoms, and the radiological findings are not different from those of other GB tumors. Physicians rarely encounter patients with carcinoid tumors because they are often diagnosed postoperatively or postmortem.

The origin of GB carcinoid tumors is of great interest in relation to mucosal metaplasia. Recent investigations have shown that neuroendocrine cells are not present in normal GB mucosa, while their mucosa with gastric and/or intestinal metaplasia expresses a variety of multipotent stem cells or neuroendocrine cell transformation to secrete serotonin, glucagon, histamine, gastrin, or somatostatin substance[5-9]. In a study of 103 GB patients with cholelithiasis, 12 (11.7%) had intestinal metaplasia. Of these cases, CGA and serotonin were expressed in 83.3% and 50% of patients, respectively[10]. Cholelithiasis is the most important risk factor for GB cancer worldwide and is more prevalent in women; both GB adenocarcinomas and GB-NETs are also more common among women (68%)[11]. In the study by Maitra et al[12], 12 patients with GB small cell carcinoma had a positive history of gallstones; moreover, 6 of the patients were positive for CGA and neuron-specific enolase, and 7 patients had foci of adenocarcinoma. Most GB adenocarcinomas also exhibit a gastric/intestinal type of differentiation and CGA-positive cells[13,14]. There are several reports on the coexistence of GB-NETs and GB adenocarcinomas, and the possibility of a direct transition between the tumors remains an intriguing issue. A case report by Shimizu et al[15] demonstrated that, pathologically, giant GB tumor has atypical cells with small round-to-oval nuclei and sparse eosinophilic cytoplasm; near this small cell proliferation was a focus of tubular adenocarcinoma, which showed a zone of transition from the small cell neuroendocrine pattern. In 2017, the World Health Organization (commonly known as WHO) updated the classification of NETs into three new categories (grades 1, 2, and 3 NETs) according to the proliferative ability of the tumor[16]. Noda et al[17] published an article related to carcinoid tumors of the GB with differentiated adenocarcinoma, and Sakaki et al[18] reported a case of GB adenocarcinoma with florid neuroendocrine cell nests. Mixed endocrine non-endocrine neoplasms have been proposed for combined adenocarcinomas and neuroendocrine carcinomas. According to a previous investigation, coexistent GB-NETs and GB adenocarcinomas are interspersed with each other under a mucosal metaplastic background, indicating the transition between these tumors. However, this phenomenon was not observed in our case. The GB-NET maintained a distance from the GB adenocarcinoma, and no intestinal metaplasia was detected. In addition, the GB failed to show the presence of cholelithiasis, and only mild cholecystitis was observed. These conditions differ from those reported in the literature.

The treatment guidelines for GB-NETs are based on tumor grading. Surgery is the most efficient and only curative treatment. However, with the exception of functional NETs, which can be detected early when the tumor is still small, most NETs are large at diagnosis and thus definitive surgery is not feasible. The prognosis of GB neuroendocrine carcinoma is worse than that of other GB carcinomas, given its highly malignant biological behavior. Maitra et al[12] and Soga[19] reported that the 5-year survival rates are 8.3% and 0.0%, respectively. Traditional chemotherapy using streptozotocin, fluorouracil, doxorubicin, cisplatin, and etoposide is a mainstay treatment for grade 3 neuroendocrine cell carcinoma of the GB, but there are no reported cases of long-term survival. Remarkably, our case of synchronous early GB adenocarcinoma and grade II GB-NET (WHO) was completely resected by surgery, and there was no need for adjuvant therapy.

IgG4-related sclerosing disease (IgG4-RD), a systemic inflammatory syndrome characterized by obliterative phlebitis and extensive infiltration of IgG4-positive plasma cells and lymphocytes with fibrosis in multiple organs including the digestive tract[20-22], has been increasingly recognized in the past few years. IgG4-RD is a benign disease that often mimics malignant behavior; however, to date, there are no reports in the English-language literature of any association with malignant potential. In our case, the patient was suspected to have this disease due to distal CBD stricture and elevated IgG4 Level; hence, it is critical to differentiate IgG4-RD from the unknown nature of a biliary stricture. The possibility of pancreatic cancer, autoimmune pancreatitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, CBD cancer, and IgG4 sclerosing cholangitis should be considered in patients with distal CBD stricture. We used imaging examinations to thoroughly investigate the narrow distal CBD of this patient. Because the patient refused any invasive procedure, tissue acquisition was not performed and no definite diagnosis could be made. The patient underwent regular abdominal US exams in follow-up. After 2 years, a progressively growing GB polypoid lesion was detected, and she agreed to undergo surgery. Interestingly, histopathological examination revealed concomitant but separate adenocarcinoma and NET in the GB. Six-month follow-ups are recommended for patients with polyps of 6-9 mm in size, and elective cholecystectomy should be considered if the polyps are greater than 10 mm in diameter[23]. If patients refuse prompt surgery, follow-up investigation modalities should include enhanced computed tomography, contrast MRI, or contrast-enhanced harmonic endoscopic US[24]. In our patient, the nature of the biliary stricture was not elucidated, but the GB polyp was treated. Synchronous or metachronous GB and CBD cancer has been reported in the literature; however, this is often related to congenital anomalous biliopancreatic duct union[25]. In our patient, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography scan did not reveal the presence of a long common channel of the biliopancreatic duct.

GB carcinoid tumors are rare, especially coexisting with an adenocarcinoma component. Most combined GB carcinoid tumors and adenocarcinoma show GB-NETs with adenocarcinoma differentiation or vice versa and are often associated with cholelithiasis and/or cholecystitis. Surgical cholecystectomy is the treatment of choice for this disease. We present a case of concomitant but separate GB adenocarcinoma and GB-NET without transition changes or evident cholecystitis. The mechanism underlying the transformation of GB adenocarcinoma to GB-NETs requires further investigation in the future.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Taiwan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Salimi M, Yap RV S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 2003;97:934-959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1848] [Cited by in RCA: 1851] [Article Influence: 84.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Joel W. Karzinoid der Gallenblase. Z Allg Pathol. 1929;46:1. |

| 3. | Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, Dagohoy C, Leary C, Mares JE, Abdalla EK, Fleming JB, Vauthey JN, Rashid A, Evans DB. One hundred years after "carcinoid": epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3063-3072. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3022] [Cited by in RCA: 3244] [Article Influence: 190.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Eltawil KM, Gustafsson BI, Kidd M, Modlin IM. Neuroendocrine tumors of the gallbladder: an evaluation and reassessment of management strategy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:687-695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Delaquerriere L, Tremblay G, Riopelle JL. Argentaffine cells in chronic cholecystitis. Arch Pathol. 1962;74:142-151. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Laitio M. Goblet cells, enterochromaffin cells, superficial gastric-type epithelium and antral-type glands in the gallbladder. Beitr Pathol. 1975;156:343-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Laitio M. Morphology and histochemistry of non-tumorous gallbladder epithelium. A series of 103 cases. Pathol Res Pract. 1980;167:335-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Albores-Saavedra J, Nadji M, Henson DE, Ziegels-Weissman J, Mones JM. Intestinal metaplasia of the gallbladder: a morphologic and immunocytochemical study. Hum Pathol. 1986;17:614-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yamamoto M, Nakajo S, Miyoshi N, Nakai S, Tahara E. Endocrine cell carcinoma (carcinoid) of the gallbladder. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:292-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sakamoto H, Mutoh H, Ido K, Satoh K, Hayakawa H, Sugano K. A close relationship between intestinal metaplasia and Cdx2 expression in human gallbladders with cholelithiasis. Hum Pathol. 2007;38:66-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Randi G, Franceschi S, La Vecchia C. Gallbladder cancer worldwide: geographical distribution and risk factors. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1591-1602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 523] [Cited by in RCA: 575] [Article Influence: 30.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Maitra A, Tascilar M, Hruban RH, Offerhaus GJ, Albores-Saavedra J. Small cell carcinoma of the gallbladder: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular pathology study of 12 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:595-601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kushima R, Lohe B, Borchard F. Differentiation towards gastric foveolar, mucopeptic and intestinal goblet cells in gallbladder adenocarcinomas. Histopathology. 1996;29:443-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Albores-Saavedra J, Nadji M, Henson DE, Angeles-Angeles A. Entero-endocrine cell differentiation in carcinomas of the gallbladder and mucinous cystadenocarcinomas of the pancreas. Pathol Res Pract. 1988;183:169-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Shimizu T, Tajiri T, Akimaru K, Arima Y, Yoshida H, Yokomuro S, Mamada Y, Taniai N, Mizuguchi Y, Kawahigashi Y, Naito Z. Combined neuroendocrine cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder: report of a case. J Nippon Med Sch. 2006;73:101-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Choe J, Kim KW, Kim HJ, Kim DW, Kim KP, Hong SM, Ryu JS, Tirumani SH, Krajewski K, Ramaiya N. What Is New in the 2017 World Health Organization Classification and 8th American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging System for Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms? Korean J Radiol. 2019;20:5-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Noda M, Miwa A, Kitagawa M. Carcinoid tumors of the gallbladder with adenocarcinomatous differentiation: a morphologic and immunohistochemical study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:953-957. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Sakaki M, Hirokawa M, Sano T, Horiguchi H, Wakatsuki S, Ogata S. Gallbladder Adenocarcinoma with Florid Neuroendocrine Cell Nests and Extensive Paneth Cell Metaplasia. Endocr Pathol. 2000;11:365-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Soga J. Primary endocrinomas (carcinoids and variant neoplasms) of the gallbladder. A statistical evaluation of 138 reported cases. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2003;22:5-15. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Takahashi K, Ito H, Katsube T, Tsuboi A, Hashimoto M, Ota E, Mita K, Asakawa H, Hayashi T, Fujino K, Okamoto S. Immunoglobulin G4-related sclerosing cholecystitis presenting as gallbladder cancer: a case report. Surg Case Rep. 2015;1:120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ohara H, Okazaki K, Tsubouchi H, Inui K, Kawa S, Kamisawa T, Tazuma S, Uchida K, Hirano K, Yoshida H, Nishino T, Ko SB, Mizuno N, Hamano H, Kanno A, Notohara K, Hasebe O, Nakazawa T, Nakanuma Y, Takikawa H; Research Committee of IgG4-related Diseases; Research Committee of Intractable Diseases of Liver and Biliary Tract; Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan; Japan Biliary Association. Clinical diagnostic criteria of IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis 2012. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2012;19:536-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kitagawa S, Zen Y, Harada K, Sasaki M, Sato Y, Minato H, Watanabe K, Kurumaya H, Katayanagi K, Masuda S, Niwa H, Tsuneyama K, Saito K, Haratake J, Takagawa K, Nakanuma Y. Abundant IgG4-positive plasma cell infiltration characterizes chronic sclerosing sialadenitis (Küttner's tumor). Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:783-791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 293] [Cited by in RCA: 269] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wiles R, Thoeni RF, Barbu ST, Vashist YK, Rafaelsen SR, Dewhurst C, Arvanitakis M, Lahaye M, Soltes M, Perinel J, Roberts SA. Management and follow-up of gallbladder polyps : Joint guidelines between the European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology (ESGAR), European Association for Endoscopic Surgery and other Interventional Techniques (EAES), International Society of Digestive Surgery - European Federation (EFISDS) and European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE). Eur Radiol. 2017;27:3856-3866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Choi JH, Seo DW, Choi JH, Park DH, Lee SS, Lee SK, Kim MH. Utility of contrast-enhanced harmonic EUS in the diagnosis of malignant gallbladder polyps (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:484-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Rajekar H. Synchronous Gall Bladder and Bile Duct Cancer: A Short Series of Seven Cases and a Brief Review of Literature. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2017;7:115-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |