Published online Dec 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i35.12971

Peer-review started: June 22, 2022

First decision: August 4, 2022

Revised: August 16, 2022

Accepted: November 18, 2022

Article in press: November 18, 2022

Published online: December 16, 2022

Processing time: 174 Days and 20.6 Hours

Malignant atrophic papulosis is a rare and potentially lethal thrombo-occlusive microvasculopathy characterized by cutaneous papules and gastrointestinal perforation. The precise pathogenesis of this disease remains obscure.

We describe the case of a 67-year-old male patient who initially presented with cutaneous aubergine papules and dull pain in the epigastrium. One week after symptom onset, he was admitted to the hospital for worsening abdominal pain. Exploratory laparotomy showed patchy necrosis and subserosal white plaque lesions on the small intestinal wall, along with multiple perforations. Histological examination of the small intestine showed extensive hyperemia, edema, necrosis with varying degrees of inflammatory reactions in the small bowel wall, small vasculitis with fibrinoid necrosis and intraluminal thrombosis in the mesothelium. Based on the mentioned evidence, a diagnosis of malignant atrophic papulosis was made. We also present the case of a 46-year-old man with known cutaneous manifestations, abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting. His physical examination showed positive rebound tenderness. A computed tomography scan revealed free intraperitoneal air. He required surgical intervention on admission and then developed an esophageal perforation. He ultimately died of a massive hemor

In previously published cases of this disease, the cutaneous lesions initially appeared as small erythematous papules. Subsequently, the papules became porcelain-white atrophic depression lesions with a pink, telangiectatic peripheral rim. In one of the patients, the cutaneous lesions appeared as aubergine papules. The other patient developed multiple perforations in the gastrointestinal tract. Due to malignant atrophic papulosis affecting multiple organs, many authors speculated that it is not a specific entity. This case series serves as additional evidence for our hypothesis.

Core Tip: Malignant atrophic papulosis is a rare and potentially lethal thrombo-occlusive microvasculopathy characterized by cutaneous papules and gastrointestinal perforation.

- Citation: Li ZG, Zhou JM, Li L, Wang XD. Malignant atrophic papulosis: Two case reports. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(35): 12971-12979

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i35/12971.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i35.12971

Degos disease, also known as Kohlmeier-Degos disease, is a rare thrombo-occlusive microvasculopathy of unknown pathogenesis[1]. Only 200 to 300 cases have been described in the literature to date[2]. It was first reported by Kohlmeier[3] in 1941 and subsequently described as a separate entity by Degos[4] in 1942. The following 2 subtypes have been described: benign atrophic papulosis limited to the skin and malignant atrophic papulosis (MAP) that involves multiple organs[5]. MAP is a potentially lethal microvasculopathy characterized by cutaneous papules that appear on the patients’ skin with porcelain-white atrophy of the center and telangiectatic edge[2]. Moreover, MAP can lead to perforation, thrombosis and hemorrhage in the gastrointestinal and central nervous system[6-8]. It was also reported that the cardiovascular system can be affected by MAP[9].

The disease is thought to be caused by complement-mediated injury to endothelial cells and presents as cutaneous and systemic manifestations[10-12]. The precise mechanism remains obscure. It is suggested that the primary dysfunction of endothelial cells, coagulopathy and vasculitis may be the etiology[13]. The C5b-9 and IFN-α levels may play a pivotal role in vascular and muscle injuries[14]. For patients with MAP, no consistently effective treatment can disrupt the natural course of the disease[2]. According to a previous study, possible papulosis in internal systems can be found in 30% of cases, and it eventually contributes to bowel vasculopathy[15,16]. We described two patients with MAP who developed catastrophic bowel perforations and died of sepsis or massive hemorrhage. Our purpose in reporting a series of case reports was to record both the classic and unreported clinical features of MAP to further aid in disease diagnosis and prognostication.

Case 1: A 67-year-old male patient suffered from dull pain in the epigastrium and cutaneous aubergine papules for 1 wk. He complained of nausea, vomiting and worsening abdominal pain for 2 d.

Case 2: A 46-year-old male complained of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, cutaneous papules and scabs on both lower extremities for 2 d.

Case 1: This patient initially presented with a 1-wk history of cutaneous aubergine papules, which were approximately 0.2 cm-0.5 cm in diameter, on the torso and limbs, along with dull pain in the epigastrium. One week after symptom onset, he was admitted to the hospital for nausea, vomiting and worsening abdominal pain.

Case 2: This patient was admitted to the hospital for complaints of a 2-d history of abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, along with cutaneous papules and scabs on both lower extremities.

Case 1: This patient had a history of gastric ulcer for 3 years. He was not treated with a proton-pump inhibitor.

Case 2: He underwent appendectomy 7 mo prior, with a quick postoperative recovery.

Cases 1 and 2: There is no personal and family history.

Case 1: Physical examination revealed diffuse abdominal tenderness, muscle tension and rebound pain.

Case 2: The patient’s abdomen was rigid.

Case 1: The levels of cardiac markers, including myoglobin, troponin T, brain natriuretic peptide and creatine kinase isoenzyme MB, were elevated. Coagulation function tests showed that the results of the D-dimer assay were four times higher than the normal value. At the initial stage of hospitalization, a serum immunoglobulin assay showed that the levels of immunoglobulin A (IgA, 2800.00 mg/L) and IgM (1910.00 mg/L) were within the reference value range, but there were elevations in the levels of IgG (21.50 g/L) and IgE (74.80 IU/L).

Case 2: The levels of IgA, IgG, IgM and C3 were lower than the reference values. Similar to the previous patient, he had a significant rise in cardiac markers and D-dimer levels. Laboratory tests, including anti-keratin antibody, antinuclear antibody, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody and anti-ds DNA antibody, were within normal limits.

Case 1: A computed tomography scan of the abdomen revealed free intraperitoneal air and intraperitoneal free fluid (Figure 1A and B).

Case 2: A computed tomography scan revealed free intraperitoneal air (Figure 1C).

Cases 1 and 2: MAP, gastrointestinal tract perforation.

Case 1: Emergent exploratory laparotomy revealed that the patient had 800 mL of feculent contents in the peritoneal cavity, patchy necrosis and subserosal white plaque lesions on the small bowel wall and multiple perforations (Figure 2A and B). Considering the diffuse involvement of the small bowel, resection was performed 80 cm distal to the Treitz ligament and 10 cm proximal to the ileocecal region.

Case 2: The patient underwent a proximal ileostomy. The intraoperative findings included the multiple perforations found at the terminal ileum (Figure 2C).

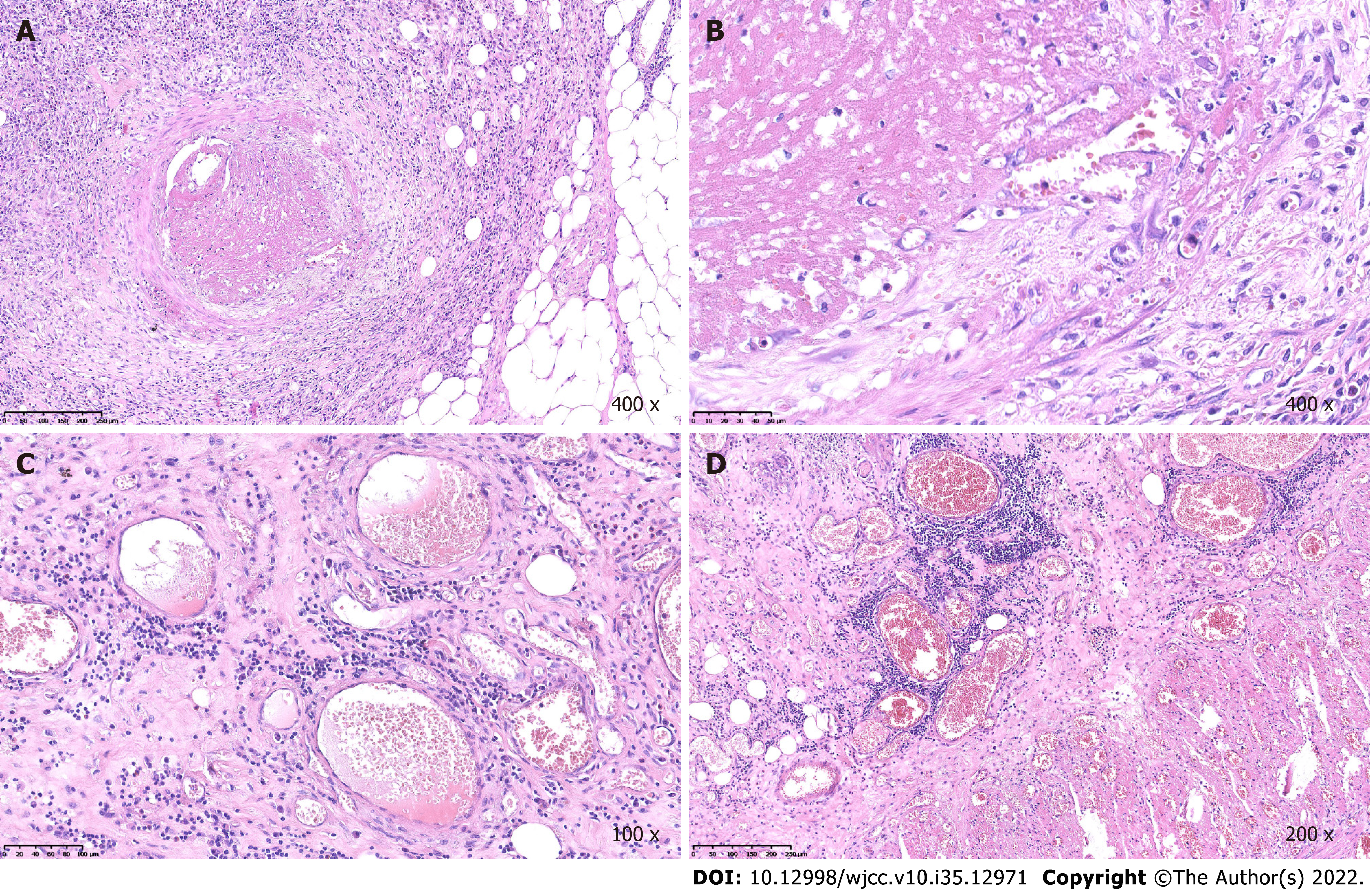

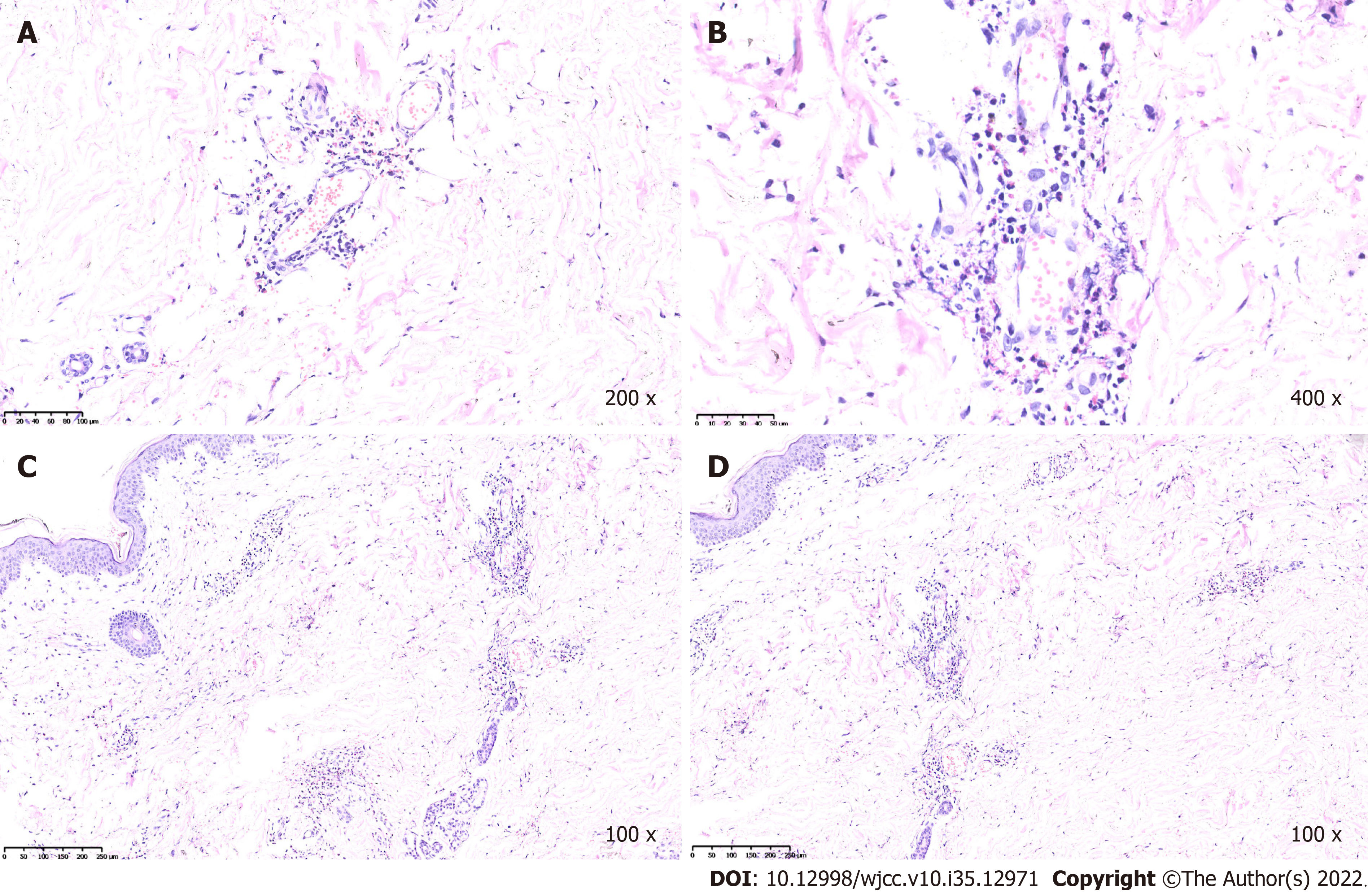

Case 1: During recovery, the aubergine papules reappeared on both lower extremities (Figure 3). Histological examination of the small bowel showed extensive hyperemia, edema, necrosis with varying degrees of inflammatory reaction, small vasculitis with fibrinoid necrosis and intraluminal thrombosis in the mesothelium (Figure 4A-D). A biopsy of the cutaneous lesions revealed that the endothelium of the small vessels in the dermis were swollen; eosinophils, neutrophils, lymphocytes and broken leukocytes were observed around the vessels. There was erythrocyte exosmosis (Figure 5A-D). Laboratory workup were persistently negative for anti-keratin antibody, antinuclear antibody, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody, anti-dsDNA antibody, anti-extractable nuclear antigen antibody repertoire and antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody. Based on the mentioned evidence, a diagnosis of malignant atrophic papulosis was made. During recovery, the patient developed fever and other symptoms of infection and was treated with intravenous ceftriaxone, which was ineffective. After that, the results of the bacterial culture that grew Escherichia coli showed that this bacteria was a carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Further anti-infection treatment with amikacin and meropenem was unsatisfactory. The patient’s condition gradually deteriorated, and he eventually died of sepsis and septic shock within 4 mo.

Case 2: Postoperative digestive tract radiography and gastroscopy revealed esophageal perforation (Figure 6A) and multiple ulcerations in the stomach (Figure 6B-D), respectively. The patient developed a massive hemorrhage from esophageal perforation and eventually died. In view of the patient’s bleeding condition, prior to his death, we administered blood replenishment treatment, performed abdominal exploration and found a large amount of hemorrhage from the esophagus. Subsequently, emergency gastroscopy was performed, and blood was seen and was coming from the perforation of the esophagus. An esophageal perforation with thoracic aorta hemorrhage was considered.

Historically, the diagnosis of Degos disease has been made clinically and confirmed histologically[8]. The initial cutaneous lesions appear as small, round, pink papules. Subsequently, the papules become a porcelain-white atrophic depressed lesion with a pink, telangiectatic peripheral rim[2,5,9]. These atrophic papules are usually scattered on the torso and limbs and are seldom distributed across the scalp, face, palms of the hands and soles of the feet. Cutaneous lesions seem to be the onset symptom and are present in almost all patients[17]. The first manifestations of the disease can appear at any time but predominantly appear between the second and fifth decades of life. Approximately 63.8% of patients develop systemic manifestations[18]. After the skin, the gastrointestinal tract is the next most common extracutaneous involved system[7]. The nervous system is the third most commonly involved system.

MAP is a rare and serious disease. Its common clinical symptoms are still not fully understood. There are many cases that have not been described, especially those that mimic or have similar presentations as our patients, who had symptoms such as hemorrhage and perforation[12,19]. The typical histological findings are noninflammatory and arterial thrombosis and wedge-shaped dermoepidermal necrotic lesions due to thrombotic occlusion of the small arteries in the corium[20,21]. MAP has been shown to be associated with infarcts of multiple organs, such as the skin, gastrointestinal tract, central nervous system, lung and myocardium[22].

The pathogenesis of Degos disease has been suspected to involve the complement cascade. Magro et al[14] discovered abundant deposits of C5b-9 within the cutaneous vasculature, implying that complement C5 inhibitors could be therapeutic. Eculizumab is a complement C5 inhibitor that prevents the cleavage of complement C5 into its proinflammatory components, and it is an effective therapy for delaying disease progression[12]. Treprostinil is a prostacyclin analogue that inhibits platelet aggregation and was recently reported as the mainstay therapy for MAP23. Several drugs, including aspirin, intravenous immunoglobulin, warfarin, corticosteroids, cyclosporin, methotrexate, azathioprine and heparin, have produced unsatisfactory results. MAP is a multiorgan microvasculopathy syndrome defined by cutaneous, gastrointestinal and central nervous system infarcts. More than half of patients die within 2-3 years, and the leading cause of death is gastrointestinal perforation. With the help of direct immunofluorescence, Pukhalskaya et al[24] found strong granular IgM deposition at the dermal-epidermal junction.

In the diagnosis and treatment of these 2 cases, a comprehensive multidisciplinary cooperation was organized with dermatologists, hematologists and pathologists. We mainly excluded some of the diseases that have similar clinical symptoms to MAP and understood the macro- and micropathological changes of MAP. Although the clinical manifestations of these cases are similar to those of Henoch-Schönlein purpura and Behçet’s disease (BD), they are different in terms of diagnosis and histopa

In the previously published cases, the cutaneous lesions initially appeared as small erythematous papules. Subsequently, the papules become porcelain-white atrophic depression lesions with a pink, telangiectatic peripheral rim. For the patient in case 1, the cutaneous lesions appeared as aubergine papules. We speculated that this disease is not a specific entity and is a distinctive pattern of the common endpoint of various vascular insults. The patient in case 2 manifested with skin lesions compatible with classic MAP. Nevertheless, according to the literature, gastrointestinal injuries are mainly concentrated in the lower digestive tract. Damage to the upper digestive tract (esophageal perforation and gastric ulcers in case 2) is rare. We speculate that MAP can lead to lesions in any organ of the gastrointestinal system. Since the levels of IgA, IgM and IgG in these two patients had completely different reactions to this disease, the influence of MAP on immunoglobulin remains uncertain.

In previously published cases of this disease, the cutaneous lesions initially appeared as small erythematous papules. Subsequently, the papules became porcelain-white atrophic depression lesions with a pink, telangiectatic peripheral rim. In one of the patients, the cutaneous lesions appeared as aubergine papules. The other patient developed multiple perforations in the gastrointestinal tract. Due to malignant atrophic papulosis affecting multiple organs, many authors speculated that it is not a specific entity. This case series serves as additional evidence for our hypothesis.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Pathology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Nakaji K, Japan; Shelat VG, Singapore S-Editor: Xing YX L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Hohwy T, Jensen MG, Tottrup A, Steiniche T, Fogh K. A fatal case of malignant atrophic papulosis (Degos' disease) in a man with factor V Leinden mutation and lupus anticoagulant. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86:245-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Theodoridis A, Makrantonaki E, Zouboulis CC. Malignant atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease) - a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kohlmeier W. Multiple Hautneknosen bei Thromboangiitis obliterans. Arch Dermatol Syphilol. 1941;181:783-784. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Degos R DJ, Tricot R. Dermatite papulosquameuse atrophiante. ull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1942;49:148-150. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lu JD, Sachdeva M, Silverberg OM, Shapiro L, Croitoru D, Levy R. Clinical and laboratory prognosticators of atrophic papulosis (Degos disease): a systematic review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16:203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | High WA, Aranda J, Patel SB, Cockerell CJ, Costner MI. Is Degos' disease a clinical and histological end point rather than a specific disease? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:895-899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Day W, Gabriel C, Kelly RE Jr, Magro CM, Williams JV, Werner A, Gifford L, Lapsia SP, Aguiar CL. Juvenile dermatomyositis resembling late-stage Degos disease with gastrointestinal perforations successfully treated with combination of cyclophosphamide and rituximab: case-based review. Rheumatol Int. 2020;40:1883-1890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Beato Merino MJ, Diago A, Fernandez-Flores A, Fraga J, García Herrera A, Garrido M, Idoate Gastearena MA, Llamas-Velasco M, Monteagudo C, Onrubia J, Pérez-González YC, Pérez Muñoz N, Ríos-Martín JJ, Ríos-Viñuela E, Rodríguez Peralto JL, Rozas Muñoz E, Sanmartín O, Santonja C, Santos-Briz A, Saus C, Suárez Peñaranda JM, Velasco Benito V. Clinical and Histopathologic Characteristics of the Main Causes of Vascular Occusion - Part II: Coagulation Disorders, Emboli, and Other. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2021;112:103-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wang HY, Zhang XL. A Case of Malignant Atrophic Papulosis With Multiple Complications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:2164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Burgin S, Stone JH, Shenoy-Bhangle AS, McGuone D. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 18-2014. A 32-Year-old man with a rash, myalgia, and weakness. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2327-2337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Umemura M, Miwa Y, Yanai R, Isojima S, Tokunaga T, Tsukamoto H, Takahashi R, Yajima N, Kasama T, Takahashi N, Sueki H, Yamaguchi S, Arai K, Takeuchi Y, Ohike N, Norose T, Yamochi-Onizuka T, Takimoto M. A case of Degos disease: demonstration of C5b-9-mediated vascular injury. Mod Rheumatol. 2015;25:480-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sathiyaraj A, Jayakumar P, McGlennon MR, Eckford JF, Anne SI. Bowel perforation from malignant atrophic papulosis treated with eculizumab. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2020;34:111-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ball E, Newburger A, Ackerman AB. Degos' disease: a distinctive pattern of disease, chiefly of lupus erythematosus, and not a specific disease per se. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:308-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Magro CM, Poe JC, Kim C, Shapiro L, Nuovo G, Crow MK, Crow YJ. Degos disease: a C5b-9/interferon-α-mediated endotheliopathy syndrome. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135:599-610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Beales IL. Malignant atrophic papulosis presenting as gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Theodoridis A, Konstantinidou A, Makrantonaki E, Zouboulis CC. Malignant and benign forms of atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease): systemic involvement determines the prognosis. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:110-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Jang MS, Park JB, Yang MH, Jang JY, Kim JH, Lee KH, Kim GT, Hwangbo H, Suh KS. Degos-Like Lesions Associated with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:215-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zouboulis CC, Theodoridis A, Makrantonaki E. Inflammation and thrombo-occlusive vessel signalling in benign atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Tummidi S, Nagendran P, Gedela S, Ramani JR, Shankaralingappa A. Degos disease: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2020;14:204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ali YN, Hamed M, Azita N. Lethal systemic degos disease with prominent cardio-pulmonary involvement. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:564-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Soter NA, Murphy GF, Mihm MC, Jr. Lymphocytes and necrosis of the cutaneous microvasculature in malignant atrophic papulosis: a refined light microscope study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;7:620-630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kaleta KP, Jarienė V, Theodoridis A, Nikolakis G, Zouboulis CC. Atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease) revisited: a cross-sectional study on 105 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Razanamahery J, Payet-Revest C, Mareschal A, Saizonou I, Bonnet L, Gil H, Humbert S, Magy-Bertrand N. Early failure of eculizumab in a patient with malignant atrophic papulosis: Is it time for initial combination therapy of eculizumab and treprostinil? J Dermatol. 2020;47:e22-e23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Pukhalskaya T, Stiegler J, Scott G, Richardson CT, Smoller B. Degos Disease (Malignant Atrophic Papulosis) With Granular IgM on Direct Immunofluorescence. Cureus. 2021;13:e12677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ozen S, Pistorio A, Iusan SM, Bakkaloglu A, Herlin T, Brik R, Buoncompagni A, Lazar C, Bilge I, Uziel Y, Rigante D, Cantarini L, Hilario MO, Silva CA, Alegria M, Norambuena X, Belot A, Berkun Y, Estrella AI, Olivieri AN, Alpigiani MG, Rumba I, Sztajnbok F, Tambic-Bukovac L, Breda L, Al-Mayouf S, Mihaylova D, Chasnyk V, Sengler C, Klein-Gitelman M, Djeddi D, Nuno L, Pruunsild C, Brunner J, Kondi A, Pagava K, Pederzoli S, Martini A, Ruperto N; Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation (PRINTO). EULAR/PRINTO/PRES criteria for Henoch-Schönlein purpura, childhood polyarteritis nodosa, childhood Wegener granulomatosis and childhood Takayasu arteritis: Ankara 2008. Part II: Final classification criteria. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:798-806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1067] [Cited by in RCA: 856] [Article Influence: 57.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Li C, Li L, Wu X, Shi J, Liu J, Zhou J, Wang L, Tian X, Zeng X, Zheng W. Clinical manifestations of Behçet's disease in a large cohort of Chinese patients: gender- and age-related differences. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39:3449-3454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Criteria for diagnosis of Behçet's disease. International Study Group for Behçet's Disease. Lancet. 1990;335:1078-1080. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Davatchi F, Chams-Davatchi C, Shams H, Shahram F, Nadji A, Akhlaghi M, Faezi T, Ghodsi Z, Sadeghi Abdollahi B, Ashofteh F, Mohtasham N, Kavosi H, Masoumi M. Behcet's disease: epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2017;13:57-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |