Published online Nov 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i32.11775

Peer-review started: May 12, 2022

First decision: August 4, 2022

Revised: August 9, 2022

Accepted: October 17, 2022

Article in press: October 17, 2022

Published online: November 16, 2022

Processing time: 180 Days and 1.3 Hours

Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (CRS/ HIPEC) for peritoneal surface malignancy can effectively control the disease, however it is also associated with adverse effects which may affect quality of life (QoL).

To investigate early perioperative QoL after CRS/HIPEC, which has not been discussed in Taiwan.

This single institution, observational cohort study enrolled patients who received CRS/HIPEC. We assessed QoL using the Taiwanese version of the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI-T) and European Organization Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30). Participants completed the questionnaires before CRS/HIPEC (S1), at the first outpatient follow-up (S2), and 3 mo after CRS/HIPEC (S3).

Fifty-eight patients were analyzed. There was no significant perioperative difference in global health status. Significant changes in physical and role functioning scores decreased at S2, and fatigue and pain scores increased at S2 but returned to baseline at S3. Multiple regression analysis showed that age and performance status were significantly correlated with QoL. In the MDASI-T questionnaire, distress/feeling upset and lack of appetite had the highest scores at S1, compared to fatigue and distress/feeling upset at S2, and fatigue and lack of appetite at S3. The leading interference items were working at S1 and S2 and activity at S3. MDASI-T scores were significantly negatively correlated with the EORTC QLQ-C30 results.

QoL and symptom severity improved or returned to baseline in most categories within 3 mo after CRS/HIPEC. Our findings can help with preoperative consultation and perioperative care.

Core Tip: Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (CRS/HIPEC) for peritoneal surface malignancy is associated with adverse effects which may affect quality of life (QoL). We aimed to investigate QoL after CRS/HIPEC, which has not previously been discussed in Taiwan. We prospectively enrolled patients from our center between 2018 and 2021. Our data showed that age and performance status were significantly correlated with QoL. In addition, QoL and symptom severity improved or returned to baseline in most categories within 3 mo after CRS/HIPEC. Our findings can help with preoperative consultation and perioperative care.

- Citation: Wang YF, Wang TY, Liao TT, Lin MH, Huang TH, Hsieh MC, Chen VCH, Lee LW, Huang WS, Chen CY. Quality of life and symptom distress after cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(32): 11775-11788

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i32/11775.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i32.11775

Peritoneal surface malignancy (PSM) is the spread of cancer cells inside the abdominal cavity, especially over the peritoneum, the membrane that covers the abdominal cavity. PSM was considered to be a terminal stage of cancer, and hence patients with PSM were often treated with palliative systemic therapies or supportive care[1-3]. PSM may cause abdominal distension, ascites, malnutrition, cachexia, and intestinal obstruction, which in turn can cause physical and mental discomfort, significantly reducing the quality of life (QoL) and shortening survival[1,4-6].

However, cytoreductive surgery (CRS) combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) has become a treatment option beyond palliative treatment for patients with PSM[1,7]. Although CRS/HIPEC can prolong survival, it can also cause adverse effects such as postoperative ileus, wound infection, intra-abdominal abscess, bleeding, symptomatic pleural effusion, anastomotic leakage, and renal damage[7-10]. Although some of these adverse effects are short term, some may persist for a long time. The potential survival benefit must therefore be weighed against a possible reduction in QoL associated with the procedure and its complications. In addition, uncertainty of the illness and facing aggressive treatment may affect the emotional well-being of the patient[11]. Therefore, the QoL after CRS/HIPEC is an important issue[4,5].

In recent years, several Western studies have investigated the QoL after CRS/HIPEC. In a systematic review, Shan et al[4] reported that CRS/HIPEC for PSM could confer small to medium benefits for health-related QoL. However, the authors concluded that the results should be interpreted with caution due to the small studies and varying follow-up duration. Several studies have reported that the QoL of patients usually declines after surgery, but then recovers to baseline and improves in 3 to 6 mo[2,3,5,6,12]. However, most of these reported were retrospective QoL or clinical data studies. In addition, only two studies on Asian patients have been reported, and although they reported that QoL would recover in 6-18 mo after CRS/HIPEC, they both enrolled a small number of patients[2,13]. Taken together, these previous studies have all focused on the QoL 3 mo or later after surgery. Investigations of perioperative QoL and symptom severity after CRS/HIPEC are limited. However, perioperative psychological distress and changes in QoL are crucial, because they may decrease treatment acceptance by the patients and affect perioperative care by the physicians.

HIPEC has been reimbursed by the National Health Insurance system since 2019 in Taiwan, and the number of patients undergoing CRS/HIPEC has gradually increased. Consequently, the impact on QoL of this treatment has also gradually become more important due to socio-economic considerations. Contemporary cancer treatment focuses on both survival and the relief of symptoms to improve function and the QoL of patients. Thus, we conducted this prospective study to investigate changes in QoL in the perioperative stage after CRS/HIPEC, and explore the factors associated with these changes.

This was a prospective, single institution, cohort study in Taiwan. The inclusion criteria were: (1) Patients who planned to receive CRS/HIPEC at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Chiayi from September 1, 2018 to February 28, 2021; and (2) patients aged ≥ 20 years. The exclusion criteria were: (1) Patients who had psychiatric disorders; (2) patients unable to understand the questionnaires; or (3) patients who were not willing to complete all questionnaires. The participants were asked to complete the questionnaires at three time points (first visit, before CRS/HIPEC; second visit, the first outpatient follow-up after CRS/HIPEC; and third visit, the outpatient visit 3 mo after CRS/HIPEC). We defined the first visit as S1, second visit as S2, and third visit as S3. Data were collected using the Taiwan version of the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI-T), and Traditional Chinese version of the Core Quality of Life Questionnaire compiled by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC QLQ-C30). All questionnaires were completed in face-to-face interviews with the researchers and patients. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chang Gung Medical Hospital (No. 201800726B0). The informed consent was obtained by all participants.

MD anderson symptom inventory: Symptom data were obtained using the MDASI-T[14], which contains 13 core symptom severity items and six interference items. Symptoms (pain, fatigue/tiredness, nausea, disturbed sleep, distress, shortness of breath, difficulty remembering, lack of appetite, drowsiness, dry mouth, sadness, vomiting, and numbness/tingling) were rated at their worst in the previous 24 h on a 0–10 scale, with 0 representing “not present” and 10 representing "as bad as you can imagine". The patients also rated the degree to which the symptoms interfered with various aspects of life during the past 24 h. Each interference item (general activity, mood, work [including both work outside the home and housework], relations with other people, walking ability, and enjoyment of life) was rated on a 0–10 scale, with 0 representing “did not interfere” and 10 representing “interfered completely”[15].

The health-related QoL was assessed using the EORTC QLQ-C30[16]. The questionnaire contains a total of 30 questions and covers five functional scales (physical, role, cognitive, emotional, and social function), three symptom scales (fatigue, pain, and vomiting), six symptom single item scales (dyspnea, insomnia, loss of appetite, constipation, diarrhea, and financial status), and a self-perceived global health status scale. Except for questions 29 and 30, which are answered on a scale from 1 to 7 points, the options for the other questions range from 1 (“Not at all”) to 4 (“Very much”). The scores are then converted into percent scores according to the questionnaire instruction manual. In the self-perceived global health status score and functional score, the higher the score, the better the patient’s function or QoL. While in the symptom score and single selection, the higher the score, the more severe the symptoms, meaning poor QoL.

All participants were reviewed by a multidisciplinary team (MDT) committee. The HIPEC procedure was indicated for: (1) Curative intent of peritoneal metastases from primary or recurrent malignancies with peritoneal metastases; (2) palliation to control ascites; and (3) adjuvant treatment for the prophylaxis of suspicious T4 disease from gastric cancer and colorectal cancer or tumor rupture during surgery. Before treatment, we evaluated the patient’s comprehensive medical history, physical examination, blood test, and imaging. All procedures were performed by the same HIPEC team at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chiayi, using a unified technique. The team performed CRS to remove all visible peritoneal lesions, then used the closed HIPEC technique with a PerformerTM HT system (RanD Biotech, Medolla, Italy). The perfusate was given at a dose of 2 L/m2 of body surface and temperature of 41-43 °C for 60-90 minutes according to the regimen[17]. The chemotherapeutic agents used included mitomycin, cisplatin, and doxorubicin.

Data on the patients’ characteristics, operative details, postoperative outcomes, and pathology were evaluated by the MDT committee. The prospectively collected data of the patients included demographics, pre-existing co-morbidities (diabetes, hypertension, and hepatitis), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, cancer type/disease status (primary or recurrence, histology type and grade, and peritoneal carcinomatosis index (PCI)), CRS/HIPEC parameters (chemotherapy regimen, duration, and completeness cytoreduction (CC) score[18], grade of postoperative complications according to the National Cancer Institute – Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE) v.5.0, and nutritional status according to the Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PGSGA) score.

The total sample size was calculated using Gpower version 3.1. The effect size was determined to be 0.25, and the study power and alpha value were set at 80% and 0.05, respectively. Based on these inputs, a minimum sample of 44 subjects was required. Demographic data and scale scores were reported with descriptive statistics, including number, percentage, mean (standard deviation) and median (range). The student’s t-test, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and Pearson's correlation coefficients were used to compare differences and correlations, respectively. Multiple regression analysis was used for inferential statistics. A two-sided P value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC).

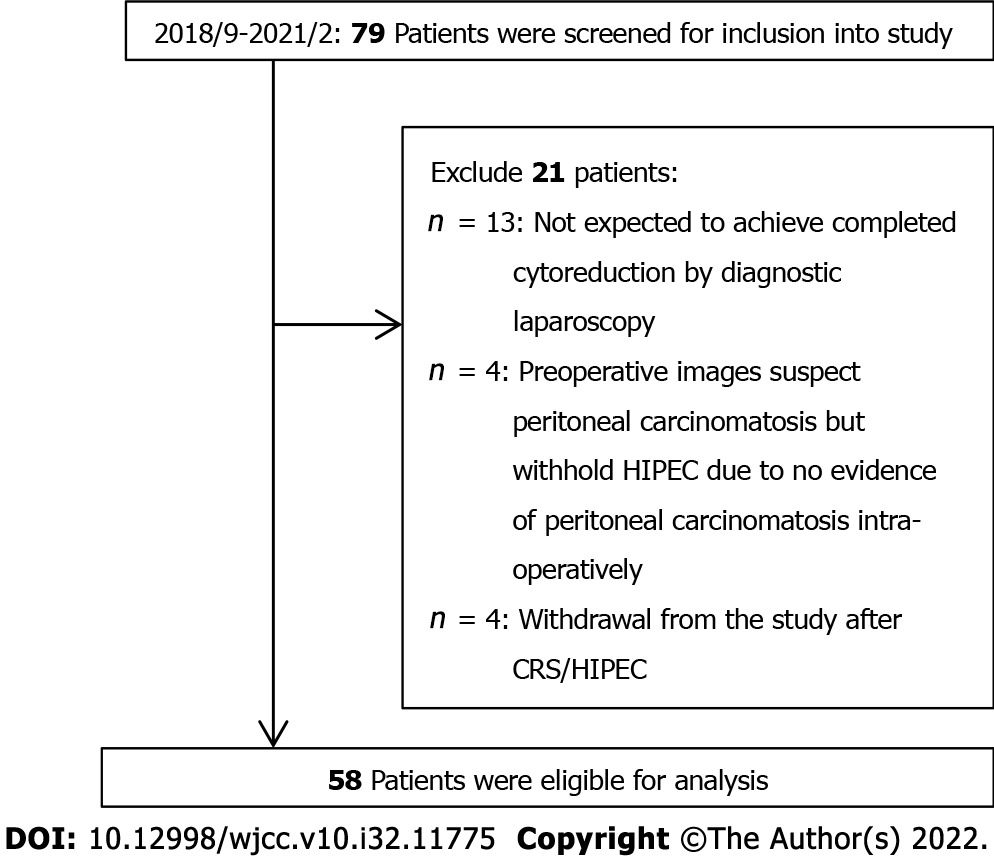

During the study period, 79 patients were screened preoperatively for enrollment into the study. However, 17 patients canceled the CRS/HIPEC procedure intraoperatively after the laparoscopic examination (13 because the disease was too extensive and cytoreduction could not be completed, and four who did not have PSM and refused to receive prophylactic HIPEC). After CRS/HIPEC, four patients withdrew from the study. Therefore, a total of 58 patients completed the study and were eligible for analysis (Figure 1). However, three patients returned to their original hospitals for further salvage therapy and did not complete the third questionnaire. The basic and disease characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. The median (range) age of all patients was 60 (22-78) years, and the most common cancer type was gastric cancer (46.6%). The median length of hospital stay was 13 days. Fifty-two patients (89.7%) had postoperative complications, of which grade I complications were the most common (72.4%). Forty-two patients (85.7%) had a PGSGA score of A.

| Variable | Number | Percentage |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 19 | 32.8 |

| Female | 39 | 67.2 |

| Age at CRS + HIPEC, years (median, range) | 60 (22-78) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 (mean, SD) | 24.3 (4.5) | |

| ECOG | ||

| 0-1 | 55 | 94.8 |

| 2 | 3 | 5.2 |

| Comorbidity | ||

| Hypertension | 17 | 29.3 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 11 | 19 |

| Hepatitis B | 5 | 8.6 |

| Hepatitis C | 6 | 10.3 |

| Primary or recurrent tumor | ||

| Primary | 41 | 70.7 |

| Recurrent | 17 | 29.3 |

| Primary cancer | ||

| Colorectal | 9 | 15.5 |

| Ovarian | 15 | 25.9 |

| Gastric | 27 | 46.6 |

| Others | 7 | 12.1 |

| Previous definitive surgery | ||

| No | 35 | 60.3 |

| Yes | 23 | 39.7 |

| Previous systemic chemotherapy | ||

| Never | 22 | 37.9 |

| 1st line | 23 | 39.7 |

| 2nd lines or more | 13 | 22.4 |

| PCI (median, range) | 5.5 (0-39) | |

| Completeness of cytoreduction score | ||

| 0 | 46 | 79.3 |

| 1 | 8 | 13.8 |

| 2 | 1 | 1.7 |

| 3 | 3 | 5.2 |

| Duration of peritonectomy, mins (median, range) | 240 (0-610) | |

| Length of hospital stay, days (median, range) | 13 (7-39) | |

| Surgical method | ||

| Laparotomy | 53 | 91.4 |

| Laparoscopy | 5 | 8.6 |

| HIPEC regimen | ||

| Cisplatin | 43 | 74.1 |

| Non-cisplatin | 15 | 25.9 |

| HIPEC indication | ||

| Adjuvant | 16 | 27.6 |

| Curative | 39 | 67.2 |

| Palliation | 3 | 5.2 |

| Duration of HIPEC, mins | ||

| 60 | 46 | 75.9 |

| 90 | 12 | 20.7 |

| Post-op complications | ||

| No | 6 | 10.3 |

| Yes | 52 | 89.7 |

| Post-op complications | ||

| Grade I | 42 | 72.4 |

| Grade II | 6 | 10.3 |

| Grade III | 3 | 5.2 |

| Grade IV | 1 | 1.7 |

| Nutrition (PGSGA score) | ||

| A | 42 | 85.7 |

| B | 7 | 14.3 |

The results of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and MDASI-T questionnaires are shown in Table 2. The average preoperative global health status scores at S1, S2, and S3 were 60.3, 56.6, and 64.4, respectively. The results showed a trend of a reduction in global health status after surgery and then an improvement at S3, however there was no statistical difference (P = 0.065). On the functional scale, there were significant decreases in the physical function (P = 0.001) and role function (P = 0.004) scores at S2, which then recovered to the preoperative baseline level at S3. In the symptom and multiple-item scales, fatigue (P = 0.004) and pain (P = 0.002) significantly increased at S2. The most significant improvement at S3 was in dyspnea (P = 0.041). In the MDASI-T questionnaire, there were no significant changes in the average scores for the severity of preoperative symptoms and the degree of interference with life between S1, S2, and S3 (Table 2). In the preoperative stage, the two symptom items with the highest scores were distress/feeling upset (2.2 ± 2.1) and lack of appetite (1.7 ± 2.4). After CRS/HIPEC, the two symptom items with the highest scores were fatigue (tiredness) (2.0 ± 1.8) and distress/feeling upset (2.0 ± 2.1) at S2, and fatigue (tiredness) (2.0 ± 1.6) and lack of appetite (1.7 ± 1.8) at S3. Regarding the interference items, the items with the highest scores were working (including housework) at S1 (2.1 ± 2.9) and S2 (2.2 ± 3.0) and activity at S3 (1.5 ± 1.5).

| Scales | Items | S1 (n = 58) | S2 (n = 58) | S3 (n = 55) | P value1 | The pairwise comparison between S1/S21 | The pairwise comparison between S2/S31 | The pairwise comparison between S1/S31 |

| QLQ-C30 | 30 | 53.5 (8.6) | 57.3 (9.8) | 54.0 (9.8) | 0.066 | 0.08 | 0.152 | 0.96 |

| Global health status | 2 | 60.3 (19.4) | 56.6 (15.4) | 64.4 (17.5) | 0.065 | 0.486 | 0.051 | 0.439 |

| Functional scales | 15 | |||||||

| Physical functioning | 5 | 82.2 (15.0) | 70.5 (19.0) | 80.6 (18.2) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.007 | 0.881 |

| Role functioning | 2 | 78.7 (23.9) | 64.1 (23.9) | 76.4 (25.2) | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.022 | 0.863 |

| Emotional functioning | 4 | 74.6 (14.8) | 78.3 (17.2) | 80.6 (17.8) | 0.152 | 0.449 | 0.743 | 0.134 |

| Cognitive functioning | 2 | 84.8 (17.2) | 85.3 (13.3) | 87.3 (18.4) | 0.7 | 0.981 | 0.807 | 0.697 |

| Social functioning | 2 | 76.4 (25.8) | 74.7 (22.8) | 82.7 (20.0) | 0.155 | 0.914 | 0.157 | 0.317 |

| Symptom scales | 13 | |||||||

| Fatigue | 3 | 26.2 (16.5) | 37.5 (21.7) | 32.1 (16.9) | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.269 | 0.215 |

| Pain | 2 | 14.9 (18.4) | 27.0 (19.5) | 14.2 (17.7) | < 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.978 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 2 | 9.8 (21.2) | 8.0 (16.0) | 12.7 (19.0) | 0.413 | 0.875 | 0.386 | 0.682 |

| Dyspnea | 1 | 12.1 (17.3) | 17.8 (20.0) | 9.7 (15.3) | 0.044 | 0.189 | 0.041 | 0.756 |

| Insomnia | 1 | 23.6 (27.2) | 24.1 (26.3) | 21.2 (22.6) | 0.813 | 0.992 | 0.815 | 0.876 |

| Appetite loss | 1 | 21.3 (23.9) | 27.6 (28.0) | 27.3 (22.3) | 0.311 | 0.361 | 0.998 | 0.408 |

| Constipation | 1 | 12.1 (23.9) | 12.1 (20.4) | 17.6 (25.5) | 0.357 | 1 | 0.424 | 0.424 |

| Diarrhea | 1 | 12.6 (19.6) | 11.5 (19.3) | 17.0 (21.2) | 0.314 | 0.949 | 0.316 | 0.485 |

| Financial difficulties | 1 | 21.3 (24.7) | 21.3 (26.3) | 17.0 (23.0) | 0.571 | 1 | 0.627 | 0.627 |

| MDASI-T | 19 | |||||||

| Symptom severity | 13 | 14.8 (12.5) | 16.8 (12.8) | 15.3 (15.2) | 0.726 | 0.722 | 0.836 | 0.98 |

| Degree of interference with life | 6 | 9.6 (9.5) | 10.7 (10.0) | 7.5 (8.6) | 0.186 | 0.791 | 0.166 | 0.468 |

Table 3 shows the relationships among the EORTC QLQ-C30 and its related factors using the student’s t-test, one-way ANOVA, and Pearson's correlation coefficients. The severity score was significantly negatively correlated with preoperative global health status (r = -0.48, P < 0.001), emotional function (r = -0.34, P < 0.01), and cognitive function (r = -0.54, P < 0.001). The score of the degree of interference with life was significantly negatively correlated with preoperative global health status and all functional scales (r = -0.39 to -0.54, P < 0.01).

| Characteristic | Global health status | Physical functioning | Role functioning | Emotional functioning | Cognitive functioning | Social functioning | ||||||||||||

| S1 | S2 | S3 | S1 | S2 | S3 | S1 | S2 | S3 | S1 | S2 | S3 | S1 | S2 | S3 | S1 | S2 | S3 | |

| Age | -0.55 | -0.96 | -0.01 | -0.61 | -2.291 | -1.01 | -0.79 | -0.83 | -2.261 | -0.49 | 1.08 | -0.81 | -0.7 | -0.5 | -1.11 | -1.21 | -2.071 | -1.99 |

| Sex | -0.67 | 0.14 | -1.11 | -0.03 | -0.18 | -0.07 | -1.33 | -0.01 | -1.43 | 0.31 | 0.33 | -0.15 | -0.44 | 0.6 | -0.07 | -0.56 | -0.24 | -0.69 |

| ECOG | 1.21 | -0.84 | 0.33 | 2.782 | 0.56 | 2.071 | 3.873 | -1.02 | 1.49 | 1.29 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 1.92 | 1.79 | -0.69 | -0.47 | -1.56 | -1.04 |

| HTN | -1.23 | -0.7 | -0.44 | -0.56 | -0.84 | -0.29 | -1.47 | -0.16 | -0.05 | -0.3 | 0.52 | -0.11 | 0.41 | -1.07 | -0.4 | -1.32 | -1.23 | -0.32 |

| DM | -0.05 | -0.41 | -2.03 | -0.06 | -0.32 | -2.07 | -0.7 | 0.48 | -0.97 | -0.48 | 0.7 | -1.2 | 0.96 | 0.55 | -0.83 | -0.77 | -1.41 | -1.58 |

| HBV | 0.24 | 0.24 | 1.03 | 1.39 | 0.96 | 0.76 | -0.12 | 0.4 | -0.03 | -0.07 | 1.13 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 1.55 | 0.5 | -2.711 | -0.54 | -0.07 |

| HCV | 1.2 | 0.18 | -0.75 | 0.95 | 0.36 | 0.08 | -0.49 | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.17 | 1.34 | 0.96 | -0.62 | -0.15 | 0.92 | -0.41 | 0.59 | -0.07 |

| Primary or recurrent tumor | -0.98 | -0.39 | -1.04 | -2.03 | -0.54 | -0.82 | -1.78 | -0.73 | -1.32 | -0.79 | 0.94 | 0.24 | -0.15 | 1.48 | 0.74 | -1.52 | 0.58 | -0.39 |

| Primary cancera | 1.36 | 1.43 | 1.36 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.48 | 0.43 | 0.6 | 0.43 | 0.63 | 0.36 | 0.63 | 1.12 | 0.59 | 1.12 | 1 | 0.93 | 1 |

| Previous definitive surgery | -1.33 | -0.83 | -1.16 | -1.25 | -1.12 | -1.14 | -0.81 | -0.66 | -0.51 | -0.63 | 0.92 | 0.27 | -0.78 | -0.07 | -0.26 | -1.31 | 0.24 | -0.4 |

| Previous systemic chemotherapy | -1.57 | -1.86 | -2.151 | -0.99 | -0.9 | -1.1 | -1.37 | -1.05 | -1.52 | -0.89 | 0.43 | -0.93 | 0.29 | 0.45 | -1 | -1.37 | -0.71 | -1.99 |

| PCIb | -0.05 | -0.02 | 0.1 | -0.15 | -0.12 | -0.13 | -0.15 | -0.12 | -0.05 | -0.22 | -0.04 | 0.04 | -0.11 | 0.03 | -0.01 | -0.01 | -0.05 | -0.05 |

| CCa | 0.93 | 1.14 | 0.48 | 1.03 | 1.07 | 0.37 | 0.53 | 1.07 | 0.29 | 1.45 | 0.06 | 0.35 | 0.38 | 0.53 | 0.3 | 0.72 | 0.85 | 0.13 |

| Duration of peritonectomy (min)b | -0.06 | -0.18 | 0.11 | 0.18 | -0.21 | 0.05 | 0.09 | -0.37 | -0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.09 | -0.14 | 0.04 | -0.03 | -0.09 | -0.04 | 0.05 |

| LOS (days)b | -0.13 | 0.14 | -0.03 | -0.02 | 0.1 | -0.07 | 0 | 0.06 | -0.12 | -0.01 | 0.2 | 0.03 | -0.26 | 0.13 | -0.05 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.07 |

| Surgical method | 0.64 | -0.01 | 0.47 | 0.54 | 0.3 | 0.65 | 1.18 | 0.72 | 0.11 | 2.111 | 1.6 | 1.14 | 0.65 | 2.872 | 1.4 | 2.872 | 0.72 | -0.22 |

| HIPEC regimen | -1.11 | -0.63 | -0.52 | -0.39 | 0.89 | 2.561 | -0.15 | 0.07 | -0.12 | -0.04 | -0.35 | 0.63 | -0.66 | 0.44 | 1.93 | -0.54 | -1.38 | 0.39 |

| HIPEC indicationa | 0.95 | 0.15 | 1.16 | 1.34 | 0.44 | 0 | 0.39 | 0.47 | 0.01 | 0.93 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.22 | 0.08 | 1.54 | 1.39 | 0.15 |

| Duration of HIPEC (mins) | 0.82 | 0.44 | 0.37 | 1.01 | -0.7 | -2.131 | 0.6 | 0.48 | 0.42 | 0.62 | 1.28 | -0.04 | 0.01 | -1.46 | -2.431 | 0.84 | 1.38 | -0.1 |

| Post-op complicationsa | 0.62 | 0.54 | 2.05 | 0.69 | 0.88 | 0.19 | 0.51 | 0.99 | 0.67 | 0.4 | 0.34 | 1.34 | 2.24 | 1.51 | 1.25 | 0.48 | 1.15 | 2.61 |

| PGSGA | 1.84 | 0.49 | 1.08 | 0.79 | 0.14 | 1.28 | -1.27 | -0.78 | 0.9 | 1.16 | -0.19 | -0.44 | 1.25 | 0.42 | 1.2 | -0.55 | 0.74 | 0.6 |

| MDASI-T | ||||||||||||||||||

| SSb | -0.483 | -0.34 | -0.7 | -0.38 | -0.46 | -0.52 | -0.3 | -0.453 | -0.483 | -0.342 | -0.493 | -0.643 | -0.543 | -0.2 | -0.723 | -0.24 | -0.331 | -0.613 |

| DILb | -0.543 | -0.493 | -0.693 | -0.433 | -0.633 | -0.66 | -0.473 | -0.603 | -0.693 | -0.433 | -0.433 | -0.723 | -0.392 | -0.281 | -0.673 | -0.533 | -0.523 | -0.783 |

At S2, the physical and social function scores of the patients who were ≥ 55 years old were significantly higher than those of the patients who were < 55 years old (P < 0.05). The symptom severity score was significantly negatively correlated with role function (r = -0.45, p < 0.001), emotional function (r = -0.49, P < 0.001) and social function (r = -0.33, P < 0.05). The degree of interference with life scores was significantly negatively correlated with global health status and all functional scales (r = -0.28 to

At S3, the role function score in those who were ≥ 55 years old was significantly higher than in those who were < 55 years old (P < 0.05). The scores of global health status in the patients who received chemotherapy before surgery were significantly higher than in those who did not (P < 0.05). The symptom severity score was significantly negatively correlated with role function, emotional function, cognitive function, and social function (r = -0.48 to -0.72, P < 0.001), and the degree of interference with life score was significantly negatively correlated with global health status, role function, emotional function, cognitive function, and social function (r = -0.67 to -0.78, P < 0.001).

The results of multiple regression analysis for the significantly correlated variables in Table 3 are shown in Table 4. The results showed that the important predictors were age ≥ 55 years old in emotional functioning at S2 (β = -0.40, P < 0.05), and ECOG performance status in preoperative physical functioning (β = 21.49, P < 0.05) and role functioning at S3 (β = 29.63, P < 0.05). Both the severity of symptoms and degree of interference with life in the MDASI-T were significantly correlated with QoL as measured using the EORTC QLQ-C30.

| Characteristic | Global health status | Physical functioning | Role functioning | Emotional functioning | Cognitive functioning | Social functioning | |||||||||||||

| S1 | S2 | S3 | S1 | S2 | S3 | S1 | S2 | S3 | S1 | S2 | S3 | S1 | S2 | S3 | S1 | S2 | S3 | ||

| Agea | -0.04 | -0.09 | -0.2 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.44 | -0.11 | 0.36 | -0.06 | -0.401 | -0.06 | -0.22 | 0.1 | -0.04 | 0.15 | 0.33 | 0.23 | |

| Sexa | -3.42 | 3.04 | -0.9 | -1.51 | 0.03 | -0.02 | -8.47 | 4.16 | -7.64 | 2.26 | 3.28 | 2.86 | -3.84 | 2.48 | 3.1 | 1.91 | 3.41 | -0.02 | |

| ECOGa | 11.48 | -3.84 | 6.95 | 21.491 | 8.54 | 15.71 | 14.12 | -15.01 | 29.631 | 4.44 | -6.42 | -7.51 | 12.7636 | 6.65 | -16.7 | -15.26 | -17.76 | -13.8 | |

| HBVa | 1.14 | -2.14 | -7.53 | -7.03 | -11.47 | -9.52 | -2.91 | -9.5 | -2.33 | 0.34 | -8.79 | -5.72 | 5.04 | -11.76 | -12.04 | 4.86 | -2.02 | -8.07 | |

| Previous systemic chemotherapya | 7.88 | 4.22 | 5.17 | 5.12 | 0.63 | -0.89 | 9.32 | -0.47 | 2.49 | 3.04 | -6.04 | -5.53 | -0.57 | -2.98 | -3.83 | 6.84 | -1.42 | -0.12 | |

| Surgical methoda | -4.57 | -0.44 | 0.86 | -2.74 | 0.36 | 8.32 | 7.11 | 8.92 | -4.39 | 9.93 | 10.61 | 11.54 | -7.77 | 17.232 | 16.781 | 33.222 | 16.73 | 2.54 | |

| HIPEC regimena | 0.65 | 1.41 | 6.69 | -0.93 | -7.51 | -6.67 | -3.94 | -4.08 | 4.79 | -2.55 | -0.21 | -0.23 | -0.85 | -2.09 | -5.98 | -1.76 | 6.71 | -0.76 | |

| MDASI-T | |||||||||||||||||||

| SSa | -0.451 | -0.07 | -0.542 | -0.21 | -0.15 | -0.01 | -0.17 | -0.15 | 0.18 | -0.1 | -0.41 | -0.11 | -0.682 | 0.07 | -0.521 | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0.10 | |

| DILa | -0.751 | -0.711 | -0.64 | -0.44 | -1.081 | -1.372 | -0.78 | -1.393 | -2.113 | -0.611 | -0.651 | -1.493 | -0.32 | -0.461 | -0.781 | -1.483 | -1.042 | -1.893 | |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.4 | 0.28 | 0.63 | 0.35 | 0.47 | 0.55 | 0.32 | 0.41 | 0.58 | 0.27 | 0.4 | 0.58 | 0.37 | 0.32 | 0.64 | 0.45 | 0.37 | 0.65 | |

This is the first prospective study to investigate the QoL and symptom distress after CRS/HIPEC in Taiwan. The results of this study showed that most patients had a significant decline in physical and role function scores at S2, but that they returned to the preoperative status at S3. We also found that the most serious symptoms after surgery were fatigue and pain, and that pain returned to the preoperative status 3 mo after surgery. There was no significant decline in global health status after surgery. Both items in the MDASI-T were significantly negatively correlated with the EORTC QLQ-C30 results. We also found that the risk factors associated with a perioperative decline in QoL were an age < 55 years old and poor ECOG performance (ECOG = 2).

Several studies have reported that patients’ functional scales, especially physical and role functional scales, declined at 3 mo and then returned to the baseline level at 6-9 mo[1,2,5,6,19]. However, we found that the physical and role function scores were lower at the first outpatient follow-up visit after surgery and then recovered to the preoperative baseline scores within 3 mo. This result is similar to that reported by Alves et al[12]. We hypothesize that the patients may have felt a loss of role function under the care of family members after surgery, and that their physical function was also limited because of surgical wounds and pain. As the wounds gradually healed, their daily role functions were restored and the functional scale scores gradually increased.

In addition, the emotional and cognitive function scores of the patients in this study showed a tendency to increase after CRS/HIPEC. This result is similar to previous studies[1,2,8,13,20]. The reason may be due to a release of anxiety over uncertainty of the surgery, and because most of the patients recognized that the cancer was being well treated and that the treatment could prolong their life. In addition, patients with positive emotions or optimistic personalities tend to have a broader scope of cognition[21].

Of the symptom scales, fatigue and pain had the worst scores at the first outpatient follow-up visit after surgery. These symptoms may be caused by laparotomy wounds and the effects of HIPEC, and have been reported in other studies[6,22]. Chia et al[2] reported that other symptoms would recover in 6-12 mo after HIPEC/CRS as well as other major surgery. In this study, the pain scales returned to baseline at 3 mo after surgery, but the other symptoms did not. In addition, 90% of the patients in this study received adjuvant chemotherapy which may have begun within 3 mo postoperatively, and this may also have contributed to the persistent symptoms.

Previous studies have reported that high PCI score, poor ECOG performance status, high CC score, longer surgery duration, and postoperative complications were related to poor QoL, and that these factors were associated with the severity of disease, complicated surgery, and prolonged recovery[2,6,7,22,23]. However, we found that PCI score, CC score, surgical duration, hospitalization duration, and postoperative complications were not associated with QoL in the perioperative period after HIPEC/ CRS. This may be due to the strict clinical criteria used in this study (e.g., 94.8% had an ECOG score £ 1 and a median PCI score of 5.5 with some receiving adjuvant HIPEC who did not have PSM) to enroll the patients with CRS/HIPEC, and this may have contributed to a better baseline physical condition.

In this study, we found that younger age (< 55 years old) was a risk factor for a decline in perioperative QoL, which is similar to previous studies[24,25]. Younger patients may have greater socioeconomic stress, lower income, and weak family support, and these may contribute to a feeling of hopelessness and low QoL[25]. We also found that the younger patients (< 55 years) had poorer emotional functioning at the early post-operative visit (S2). However, further studies are needed to include these factors in prediction models and assess their effects on QoL.

There are several strengths to this study. First, all of the patients were enrolled after the consensus of the MDT committee, and CRS/HIPEC was performed by experienced team members. Thus, the quality of perioperative care was consistent and well documented. Second, the associated clinical data were prospectively collected. In addition, to make sure that the patients could understand the questions, the questionnaires were performed by a single well-trained case manager in face-to-face interviews with the patients, and this could minimize detection bias and missing data. Third, this study focused on measuring the change in QoL in the perioperative period after CRS/HIPEC, and this could minimize interference from the subsequent adjuvant therapy.

The major limitation was some patients transferred back to their original hospital for subsequent treatment when their condition after CRS/HIPEC had become stable, so it was difficult to collect longer term questionnaires. A minor limitation was that this study included patients with different types of cancer and cancer surgery. Moreover, subgroup analyses of patients with different treatment intent and preoperative status were not performed due to the small sample size.

The balance of treatment and QoL is often a controversial issue. Our findings showed that although CRS/HIPEC resulted in a short-term decline in the QoL of patients, most functions and the severity of symptoms returned to the baseline level within 3 mo after surgery. Understanding the clinical course may relieve the patients’ anxiety over their disease. We also found that perioperative symptom severity and symptom interference with daily life in the MDASI-T were significantly correlated with the decline in specific functions. Therefore, it is important to continuously evaluate and provide timely care to improve the symptoms and symptom interference of patients undergoing CRC/HIPEC, and ultimately to improve their QoL.

Our findings of an association between younger age and poor preoperative ECOG performance status with a perioperative decline in QoL may help MDT members to identify patients undergoing CRC/HIPEC who are at high risk of perioperative symptom distress and decline in QoL. Patient counseling and perioperative support may be provided accordingly. The improvement or return to baseline in QoL and symptom severity after 3 mo highlight the importance of a MDT approach towards effective teamwork for CRS/HIPEC care.

Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (CRS/HIPEC) for peritoneal surface malignancy can effectively control the disease, however it is also associated with adverse effects which may affect quality of life (QoL).

Investigations of perioperative QoL and symptom severity after CRS/HIPEC are limited. The impact on QoL of this treatment has also gradually become more important due to socio-economic considerations.

The main objective of this study was to investigate early perioperative QoL after CRS/HIPEC, which has not previously been discussed in Taiwan.

We performed an observational, prospective, single-center cohort study and enrolled patients who received CRS/HIPEC at Chang-Gung Memorial Hospital in Chiayi between September 1, 2018 and February 28, 2021. We assessed QoL using the Taiwanese version of the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI-T) and European Organization Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30). The participants completed the questionnaires before CRS/ HIPEC (S1), at the first outpatient follow-up (S2), and 3 mo after CRS/HIPEC (S3).

Most patients had a significant decline in physical and role function scores at S2, but they returned to the preoperative status at S3. The most serious symptoms after surgery were fatigue and pain, and pain returned to the preoperative status 3 mo after surgery. There was no significant decline in global health status after surgery. Both items in the MDASI-T were significantly negatively correlated with the EORTC QLQ-C30 results. The important determinants of QoL were age ≥ 55 years old in emotional functioning at S2 (β = -0.40, P < 0.05), and performance status in preoperative physical functioning (β = 21.49, P < 0.05) and role functioning at S3 (β = 29.63, P < 0.05).

QoL and symptom severity improved or returned to baseline in most categories within 3 mo after CRS/HIPEC. Understanding the clinical course may relieve the patients’ anxiety over their disease. Our findings may help physicians with preoperative consultation and perioperative care.

As this study had a relatively small sample size and was prospective in design, larger studies with multiple centers and fewer influences factors are warranted to explore the QoL after HIPEC.

The authors are grateful to the Health Information and Epidemiology Laboratory (CLRPG6L0041), and Chia-Yen Liu, a member of the Health Information and Epidemiology Laboratory of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chiayi, for help with statistical information.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Taiwan Association of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 3235.

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: Taiwan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Dambrauskas Z, Lithuania; Shi Y, China; Yamanaka K, Japan S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Albertsmeier M, Hauer A, Niess H, Werner J, Graeb C, Angele MK. Quality of life in peritoneal carcinomatosis: a prospective study in patients undergoing cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC). Dig Surg. 2014;31:334-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chia CS, Tan GH, Lim C, Soo KC, Teo MC. Prospective Quality of Life Study for Colorectal Cancer Patients with Peritoneal Carcinomatosis Undergoing Cytoreductive Surgery and Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:2905-2913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ford J, Hanna M, Boston A, Berri R. Life after hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy; measuring quality of life and performance status after cytoreductive surgery plus hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Am J Surg. 2016;211:546-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Shan LL, Saxena A, Shan BL, Morris DL. Quality of life after cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intra-peritoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal carcinomatosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Oncol. 2014;23:199-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dodson RM, McQuellon RP, Mogal HD, Duckworth KE, Russell GB, Votanopoulos KI, Shen P, Levine EA. Quality-of-Life Evaluation After Cytoreductive Surgery with Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:772-783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ali YM, Sweeney J, Shen P, Votanopoulos KI, McQuellon R, Duckworth K, Perry KC, Russell G, Levine EA. Effect of Cytoreductive Surgery and Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy on Quality of Life in Patients with Peritoneal Mesothelioma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27:117-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Glockzin G, Schlitt HJ, Piso P. Peritoneal carcinomatosis: patients selection, perioperative complications and quality of life related to cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. World J Surg Oncol. 2009;7:5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hamilton TD, Taylor EL, Cannell AJ, McCart JA, Govindarajan A. Impact of Major Complications on Patients' Quality of Life After Cytoreductive Surgery and Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:2946-2952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Schmidt U, Dahlke MH, Klempnauer J, Schlitt HJ, Piso P. Perioperative morbidity and quality of life in long-term survivors following cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2005;31:53-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Piso P, Glockzin G, von Breitenbuch P, Popp FC, Dahlke MH, Schlitt HJ, Nissan A. Quality of life after cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal surface malignancies. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100:317-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lien CY, Lin HR, Kuo IT, Chen ML. Perceived uncertainty, social support and psychological adjustment in older patients with cancer being treated with surgery. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18:2311-2319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Alves S, Mohamed F, Yadegarfar G, Youssef H, Moran BJ. Prospective longitudinal study of quality of life following cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy for pseudomyxoma peritonei. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36:1156-1161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tan WJ, Wong JF, Chia CS, Tan GH, Soo KC, Teo MC. Quality of life after cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy: an Asian perspective. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:4219-4223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tseng TH, Cleeland CS, Wang XS, Lin CC. Assessing cancer symptoms in adolescents with cancer using the Taiwanese version of the M. D. Anderson Symptom Inventory. Cancer Nurs. 2008;31:E9-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cleeland CS, Mendoza TR, Wang XS, Chou C, Harle MT, Morrissey M, Engstrom MC. Assessing symptom distress in cancer patients: the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory. Cancer. 2000;89:1634-1646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, de Haes JC. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9802] [Cited by in RCA: 11461] [Article Influence: 358.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chen CY, Chang HY, Lu CH, Chen MC, Huang TH, Lee LW, Liao YS, Chen VC, Huang WS, Ou YC, Lung FC, Wang TY. Risk factors of acute renal impairment after cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Int J Hyperthermia. 2020;37:1279-1286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sugarbaker PH. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in the management of gastrointestinal cancers with peritoneal metastases: Progress toward a new standard of care. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016;48:42-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Macrì A, Maugeri I, Trimarchi G, Caminiti R, Saffioti MC, Incardona S, Sinardi A, Irato S, Altavilla G, Adamo V, Versaci A, Famulari C. Evaluation of quality of life of patients submitted to cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal carcinosis of gastrointestinal and ovarian origin and identification of factors influencing outcome. In Vivo. 2009;23:147-150. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Hill AR, McQuellon RP, Russell GB, Shen P, Stewart JH 4th, Levine EA. Survival and quality of life following cytoreductive surgery plus hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal carcinomatosis of colonic origin. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:3673-3679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Fredrickson BL, Branigan C. Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires. Cogn Emot. 2005;19:313-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1751] [Cited by in RCA: 1232] [Article Influence: 61.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kopanakis N, Argyriou EO, Vassiliadou D, Sidera C, Chionis M, Kyriazanos J, Efstathiou E, Spiliotis J. Quality of life after cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC: A single centre prospective study. J BUON. 2018;23:488-493. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Lustosa RJC, Batista TP, Carneiro VCG, Badiglian-Filho L, Costa RLR, Lopes A, Sarmento BJQ, Lima JTO, Mello MJG, LeÃo CS. Quality of life in a phase 2 trial of short-course hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) at interval debulking surgery for high tumor burden ovarian cancer. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2020;47:e20202534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Dunn J, Ng SK, Breitbart W, Aitken J, Youl P, Baade PD, Chambers SK. Health-related quality of life and life satisfaction in colorectal cancer survivors: trajectories of adjustment. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ravindran OS, Shankar A, Murthy T. A Comparative Study on Perceived Stress, Coping, Quality of Life, and Hopelessness between Cancer Patients and Survivors. Indian J Palliat Care. 2019;25:414-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |