Published online Nov 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i31.11542

Peer-review started: June 2, 2022

First decision: August 22, 2022

Revised: August 30, 2022

Accepted: October 9, 2022

Article in press: October 9, 2022

Published online: November 6, 2022

Processing time: 146 Days and 15.2 Hours

Aortic dissection (AoD) is a life-threatening disease. Its diversified clinical manifestations, especially the atypical ones, make it difficult to diagnose. The epileptic seizure is a neurological problem caused by various kinds of diseases, but AoD with epileptic seizure as the first symptom is rare.

A 53-year-old male patient suffered from loss of consciousness for 1 h and tonic-clonic convulsion for 2 min. The patient performed persistent hypomania and chest discomfort for 30 min after admission. He had a history of hypertension without regular antihypertensive drugs, and the results of his bilateral blood pressure varied greatly. Then the electroencephalogram showed the existence of epileptic waves. The thoracic aorta computed tomography angiography showed the appearance of AoD, and it originated at the lower part of the ascending aorta. Finally, the diagnosis was AoD (DeBakey, type I), acute aortic syndrome, hyper

The AoD symptoms are varied. When diagnosing the epileptic seizure etiologically, AoD is important to consider by clinical and imaging examinations.

Core Tip: The clinical manifestations of aortic dissection (AoD) are diverse. AoD with epileptic seizure as the first symptom is rare. Measuring blood pressure and image analysis are important to diagnose. In conclusion, it is important to consider AoD when diagnosing epileptic seizure, and surgical treatment is an important option under the right conditions.

- Citation: Zheng B, Huang XQ, Chen Z, Wang J, Gu GF, Luo XJ. Aortic dissection with epileptic seizure: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(31): 11542-11548

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i31/11542.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i31.11542

Aortic dissection (AoD) is the most common catastrophic aorta disease, which is associated with high mortality rates[1]. Usually, AoD has a series of clinical manifestations, in which chest or back pain was the most common symptom (84.8%)[2]. Some patients with AoD have no pain but symptoms of an epileptic seizure, which is likely to be missed clinically. It is difficult to distinguish various kinds of AoD from other diseases in the real clinical world[3], such as myocardial ischemia and neurological diseases.

Here, we report a case in which the first clinical manifestation of AoD is epileptic seizure. This rare case revealed that AoD symptoms could be atypical. This increases the difficulty of diagnosing AoD in a timely manner in clinical practice.

A 53-year-old male patient underwent sudden loss of consciousness and tonic-clonic convulsion for 2 min when playing cards. He was transported to the emergency department of our hospital 1 h later.

In addition to these symptoms, the patient also had froth at the mouth, trismus, and urinary incontinence for 8 min before admission. He appeared to be hypomanic and had chest discomfort for 30 min and tonic-clonic convulsion for 1 min since his admission. There were no obvious symptoms of dyspnea, headache, or dizziness.

The patient had a history of hypertension for more than 10 years without regular antihypertensive drugs. He did not know the stratification and severity of hypertension. He had no history of other diseases.

His personal and family history was unremarkable.

The general condition of the patient was fair. He showed persistent irritability for 30 min, his highest blood pressure on the left upper arm was 220/140 mmHg, and his heart rate was 112 beats per min. When the patient was quiet, his left upper arm blood pressure was 145/90 mmHg, and the right one was 185/113 mmHg. The other vital signs were stable. The neurological examination showed that his pupils were of the same size and shape, with a diameter of about 3 mm, and were sensitive to light reflexes. The other cranial nerve examinations were normal. Both his superficial and deep nerve reflections existed. The pathological signs were negative. He had visible limb activity but no pyramidal signs were detected. The neuromuscular examination displayed that his muscle tone and muscle strength were normal. He refused to do the other coordination movement examinations due to inconvenience.

The patient’s blood test indicated some abnormal items; for example, the white blood cell count was 24.09 × 109/L and the neutrophil ratio was 90.84%. The result of the lactate was 5.50 mmol/L in the biochemical test. In the myocardial enzyme spectrum test, the value of troponin I was 94.188 μg/L, the value of creatine kinase isoenzyme was 109.810 μg/L, the value of creatine kinase was 2078.00 IU/L, the value of myohemoglobin was 3717.750 μg/L, and the value of B type natriuretic peptide was 206.650 pg/mL. The results of the urine test, stool test, and coagulation test were normal.

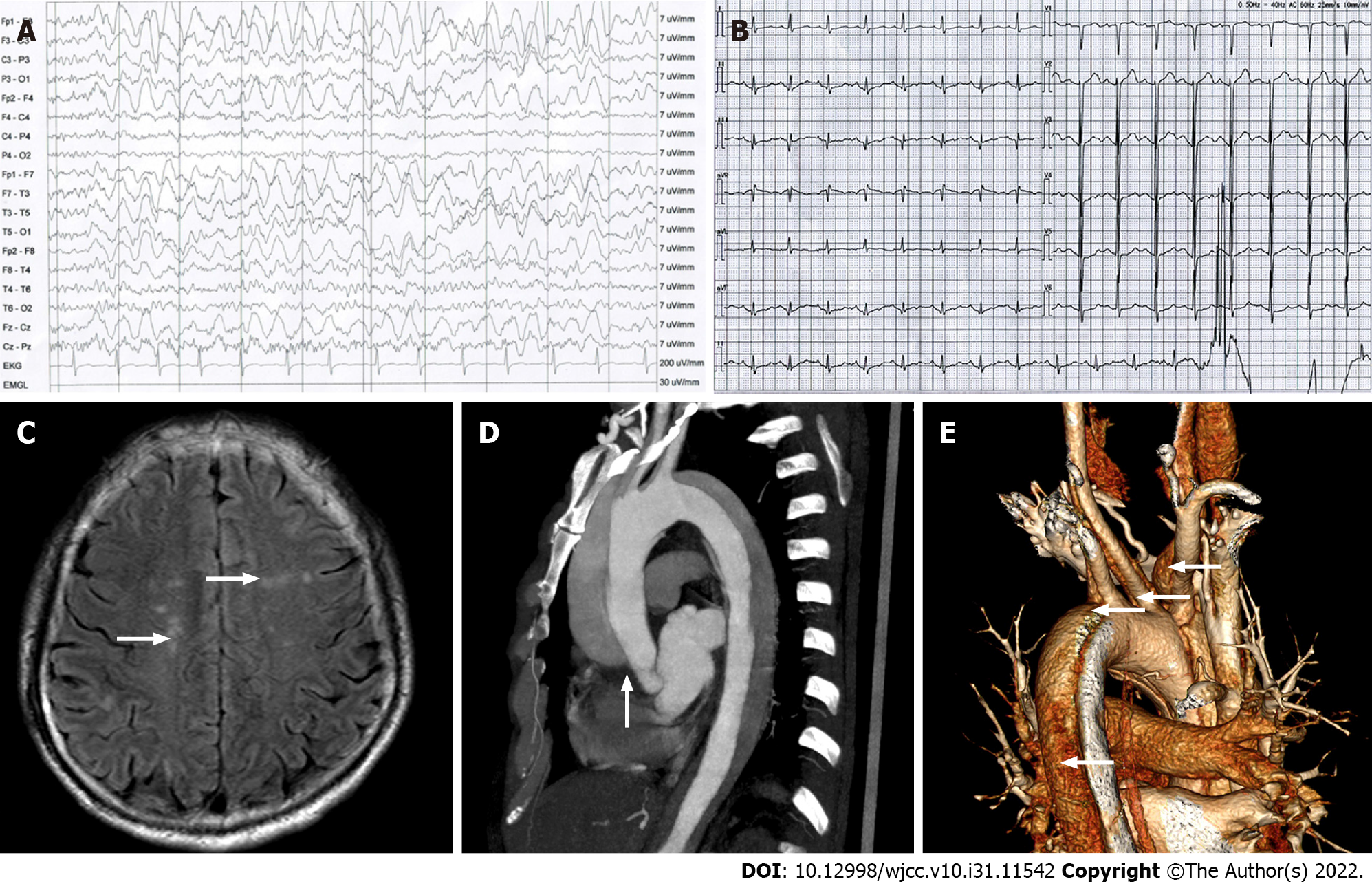

The electroencephalogram displayed 2-3 Hz moderate-high amplitude slow waves mainly in the left anterior area, frontal midline area, and right frontal polar area of the head (Figure 1A). The electrocardiogram (ECG) showed sinus rhythm and normal ECG (Figure 1B). The results of head magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were abnormal hyperintense signals (white arrows) in white matter regions of the brain, known as the centrum semiovale (Figure 1C). The thoracic aorta computed tomography angiography (CTA) exhibited that the AoD originated at the lower part of the ascending aorta, extended to the right common carotid artery, the brachiocephalic artery, the left common carotid artery, the left subclavian artery and the descending aorta (white arrows), and false lumens were filled with a contrast agent (Figure 1D and E). Other examinations were normal.

AoD (DeBakey, type I); acute aortic syndrome (AAS); hypertension (Grade 3); secondary epileptic seizure.

The patient was monitored emphatically for ECG and blood pressure. The procedures were conducted immediately including nursing guidance, health education, and drug treatment. Because the results of the myocardial enzyme spectrum test were high, it was necessary to pay attention to the myocardial damage caused by drug usage and measurement, and observe the changes in the patient. He was given a diazepam injection (10 mg) in the Emergency Department to control the symptom of irritability. After 30 min, he was transferred to the Department of Neurology for further treatment. The patient was treated by intravenous infusion with the remifentanil hydrochloride injection of 2 mg per day (6 μg/kg/h), the dexmedetomidine hydrochloride injection of 200 μg per day (0.4 μg/kg/h), the nicardipine hydrochloride injection of 2 mg per day (3 μg/kg/min), the esmolol hydrochloride injection of 100 mg per day (0.05 mg/kg/min) and the mannitol injection of 125 mL. We adjusted the specific total amount of drugs according to the clinical changes of the patient. Those sedative, analgesic and antihypertensive therapies were effective, but he had tear-like pain in front of his chest and back pain after 6 h of treatments. The pain lasted for about 1 h, and was relieved after the patient refused further treatment. Then, we further discussed a practical operation with our doctors in the Department of Thoracic and Cardiac Surgery: the ascending aorta vascular replacement + total arch replacement + descending aorta stenting repair, but he refused our surgical therapy.

After 3 d of treatment, the patient’s mental condition had recovered and there was no obvious pain. He decided to discharge from our hospital. One week later, the patient died of the ruptured AoD and hemorrhagic shock.

AoD is a challenging disease associated with high misdiagnosis and mortality rates. Generally, it occurs when either a tear or an ulcer allows blood to penetrate from the aortic lumen into the media, and the inflammatory response to blood in the media leads to aortic dilatation and rupture[2,4]. It has many risk factors including hypertension, smoking, pregnancy, the use of illicit drugs, direct blunt trauma, Marfan’s syndrome, iatrogenic factors, bicuspid aortic valve deformities, familial asymptomatic AoD, intramural hematoma expansion and arteritis[4,5]. Among these factors, hypertension is the most common, accounting for up to 75% of cases[6]. A study proved that hypertension could promote a pro-inflammatory state by increasing serum levels of interleukin 6 (IL-6), IL-8, and matrix metalloproteinase 2/9[7]. So the treatment of hypertension is an effective way to prevent and control AoD. The patient’s blood pressure in our case was not under control effectively, and the head MRI also showed high-signal ischemic lesions that may be caused by long-term unstable hypertension. Finally, he suffered from the disease.

Because these patients often had a disturbance of consciousness, aphasia and/or amnesia, most cases may be the lack of necessary medical history and the patient’s ability to complain of typical pain[8]. This makes it difficult to further study the relationship between AoD and epileptic seizure. The AoD and epileptic seizures appearing at the same time may be a coincidence. However, most studies have revealed that a certain percentage of AoD can trigger corresponding neurological symptoms as initial performance, including epileptic seizure. The study by Sasaki et al[9] demonstrated that 2 of 127 patients with type A acute AoD suffered seizures as the main symptom. Currently, the pathophysiological mechanisms between AoD and epileptic seizures have not been studied clearly. Taking carotid artery dissection as an example, the possible reasons were the disintegration and displacement of thrombus led to extensive embolization events in both hemispheres and secondary epileptic seizure[10]. Moreover, the hemodynamic changes caused by AoD could lead to thrombosis in the same way, which may cause disorders in the cardiovascular system and nervous system[11]. However, most of the studies have been case reports, with a lack of basic research on relevant mechanisms. The patient with AoD (DeBakey, type I) in the case could result in acute cerebral circulation insufficiency and microthrombosis which further led to a secondary epileptic seizure, irritability and other symptoms. Therefore, it may be catastrophic if the patient’s disease could not be diagnosed and managed promptly[12].

Diagnosis of atypical AoD requires comprehensive judgment. As an initial symptom of AoD, an epileptic seizure may make diagnosis difficult, thus increasing the mortality of AoD[10]. The study by Gaul[13] showed that neurological symptoms as the initial manifestation of AoD accounted for approximately 30% of patients. Neurological symptoms included ischemic stroke (16%), ischemic neuropathy (11%), syncope (6%), somnolence (4%), and epilepsy (3%)[14]. Luckily, we have other evidence to help diagnose AoD, such as any unexplained hypotension, mild dyspnea, chest discomfort, loss of consciousness, blood pressure, electrocardiogram changes, cardiac murmurs, and cold limbs[15]. It is beneficial to measure the pulse amplitude and blood pressure between arms especially when the difference is more than 20 mmHg in systolic blood pressure. In general, the test of the myocardial enzyme spectrum is used to identify myocardial infarction, but the increase in the myocardial enzyme spectrum also indicated that we should pay attention to the possibility of patients suffering from AoD. A result studied by Minamidate et al[16] demonstrated acute coronary artery involvement was associated with 8.0% of patients with acute type A AoD, and 62% had myocardial ischemia with creatine kinase isoenzyme elevation. The patient’s blood test results, especially the myocardial enzyme spectrum test, proved the presence of in vivo injury and increased inflammation in the myocardium. In our case, the ECG of the patient was generally normal, but the results were high in the white blood cell count, the neutrophil ratio, the lactate and myocardial enzyme spectrum. Combined with the comprehensive analysis of the patient’s clinical manifestations and imaging results, we considered that the possibility of myocardial infarction was small at the same time, and we needed to give priority to AoD. It was also necessary to regularly monitor the results of electrocardiograms and myocardial enzymes. Furthermore, the head MRI and thoracic aorta CTA are essential for all patients with neurological symptoms, especially when a patient was unconscious and could not get a detailed clinical history, or when he was complicated by cerebral infarction[17]. It should be emphasized that AoD can be classified by prognosis and therapeutic consequences in Stanford classification (type A and B)[18]. We usually use DeBakey by anatomic patterns, including type I (from the ascending aorta to the descending aorta), type II (limited in the ascending aorta), and type III (from the descending aorta to distal end) because this classification facilitates surgical treatment of AoD in detail[19]. At last, the AAS is of great value in the diagnosis of AoD. The AAS includes AoD, intramural hematoma and penetrating aortic ulcer by the specific classification of CT. The latest research showed that a new and simple diagnostic algorithm was proposed in cases of suspected AAS. First, the patient’s clinical suspicion. Then, the ECG, chest X-ray, and laboratory testing including troponins and D-dimers; Finally, the CT scan and the transthoracic echocardiography[20]. Overall, the study of diagnostic strategy of AoD had been advanced, which could better guide the treatment.

The precise surgical aorta repair for AoD patients is very important. Surgical treatment is the best choice to lower the mortality of AoD. A tailored patient treatment approach for each of these acute aortic entities was needed[20]. In recent years, it has been reported that the elephant trunk technique was feasible for different surgical strategies, and helps to save the operation and circulatory arrest times during acute total arch replacement[21,22]. It also showed simplicity, consistency, and reproducibility in chronic symptomatic AoD[23]. However, different schemes and techniques used for the aortic arch replacement in AoD patients are still controversial issues for every cardiac surgeon[24]. Despite the issues, an accurate assessment of the aortic anatomy has to be performed before any surgical repair is certain, including the extension of the dissection process, the diameters of the aorta, and the exact location between the true and the false lumen. In addition, we should consider not only the surgical treatment of AoD but also anti-epileptic drugs for psychiatric disorders. The epileptic seizure may affect the disease process of AoD through neurological and endocrine pathological dysregulation. AoD further reduces cerebral blood supply and causes a vicious cycle. Because there are not enough related researches to study, we suggest that symptomatic treatment is needed to adapt to surgical indications as soon as possible. This may bring benefits to patients.

In summary, the patient experienced type I AoD with an epileptic seizure as the first symptom. We emphasize that the possibility of AoD should be considered when diagnosing epileptic seizure. Measuring the blood pressure difference between the arms and the head and aorta image analysis is essential to the diagnosis.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Neurosciences

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: JAIN S, India; Kharlamov AN, Netherlands; Schoenhagen P, United States S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Nienaber CA, Eagle KA. Aortic dissection: new frontiers in diagnosis and management: Part I: from etiology to diagnostic strategies. Circulation. 2003;108:628-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 460] [Cited by in RCA: 390] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mussa FF, Horton JD, Moridzadeh R, Nicholson J, Trimarchi S, Eagle KA. Acute Aortic Dissection and Intramural Hematoma: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2016;316:754-763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 384] [Cited by in RCA: 336] [Article Influence: 37.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Erbel R, Alfonso F, Boileau C, Dirsch O, Eber B, Haverich A, Rakowski H, Struyven J, Radegran K, Sechtem U, Taylor J, Zollikofer C, Klein WW, Mulder B, Providencia LA; Task Force on Aortic Dissection, European Society of Cardiology. Diagnosis and management of aortic dissection. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:1642-1681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 845] [Cited by in RCA: 697] [Article Influence: 29.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nienaber CA, Powell JT. Management of acute aortic syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:26-35b. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pasternak B, Inghammar M, Svanström H. Fluoroquinolone use and risk of aortic aneurysm and dissection: nationwide cohort study. BMJ. 2018;360:k678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 23.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nienaber CA, Clough RE. Management of acute aortic dissection. Lancet. 2015;385:800-811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 361] [Cited by in RCA: 443] [Article Influence: 44.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cifani N, Proietta M, Tritapepe L, Di Gioia C, Ferri L, Taurino M, Del Porto F. Stanford-A acute aortic dissection, inflammation, and metalloproteinases: a review. Ann Med. 2015;47:441-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sakamoto Y, Koga M, Ohara T, Ohyama S, Matsubara S, Minatoya K, Nagatsuka K, Toyoda K. Frequency and Detection of Stanford Type A Aortic Dissection in Hyperacute Stroke Management. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;42:110-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sasaki H, Harada T, Ishitoya H, Sasaki O. Aorto-carotid bypass for type A acute aortic dissection complicated with carotid artery occlusion: no touch until circulatory arrest. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2020;31:263-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wang J, Wu LR, Xie X. Stanford type a aortic dissection with cerebral infarction: a rare case report. BMC Neurol. 2020;20:253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Valentine RJ, Boll JM, Hocking KM, Curci JA, Garrard CL, Brophy CM, Naslund TC. Aortic arch involvement worsens the prognosis of type B aortic dissections. J Vasc Surg. 2016;64:1212-1218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Evangelista A, Isselbacher EM, Bossone E, Gleason TG, Eusanio MD, Sechtem U, Ehrlich MP, Trimarchi S, Braverman AC, Myrmel T, Harris KM, Hutchinson S, O'Gara P, Suzuki T, Nienaber CA, Eagle KA; IRAD Investigators. Insights From the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection: A 20-Year Experience of Collaborative Clinical Research. Circulation. 2018;137:1846-1860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 446] [Cited by in RCA: 851] [Article Influence: 141.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gaul C, Dietrich W, Friedrich I, Sirch J, Erbguth FJ. Neurological symptoms in type A aortic dissections. Stroke. 2007;38:292-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gaul C, Dietrich W, Erbguth FJ. Neurological symptoms in aortic dissection: a challenge for neurologists. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;26:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Koga M, Iguchi Y, Ohara T, Tahara Y, Fukuda T, Noguchi T, Matsuda H, Minatoya K, Nagatsuka K, Toyoda K. Acute ischemic stroke as a complication of Stanford type A acute aortic dissection: a review and proposed clinical recommendations for urgent diagnosis. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;66:439-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Minamidate N, Takashima N, Suzuki T. The impact of CK-MB elevation in patients with acute type A aortic dissection with coronary artery involvement. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2022;17:169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Oon JE, Kee AC, Toh HC. A case report of Stanford type A aortic dissection presenting with status epilepticus. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29:243.e5-243.e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Peterss S, Mansour AM, Ross JA, Vaitkeviciute I, Charilaou P, Dumfarth J, Fang H, Ziganshin BA, Rizzo JA, Adeniran AJ, Elefteriades JA. Changing Pathology of the Thoracic Aorta From Acute to Chronic Dissection: Literature Review and Insights. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:1054-1065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tsagakis K, Tossios P, Kamler M, Benedik J, Natour D, Eggebrecht H, Piotrowski J, Jakob H. The DeBakey classification exactly reflects late outcome and re-intervention probability in acute aortic dissection with a slightly modified type II definition. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;40:1078-1084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Vilacosta I, San Román JA, di Bartolomeo R, Eagle K, Estrera AL, Ferrera C, Kaji S, Nienaber CA, Riambau V, Schäfers HJ, Serrano FJ, Song JK, Maroto L. Acute Aortic Syndrome Revisited: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78:2106-2125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hirano K, Tokui T, Nakamura B, Inoue R, Inagaki M, Hirano R, Chino S, Maze Y, Kato N, Takao M. Impact of the Frozen Elephant Trunk Technique on Total Aortic Arch Replacement. Ann Vasc Surg. 2020;65:206-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | An Z, Tan MW, Song ZG, Tang H, Lu FL, Xu ZY. Retrograde Type A Dissection after Ascending Aorta Involved Endovascular Repair and Its Surgical Repair with Stented Elephant Trunk. Ann Vasc Surg. 2019;58:198-204.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Sultan S, Kavanagh EP, Veerasingam D, Costache V, Elhelali A, Fitzgibbon B, Diethrich E, Hynes N. Kinetic Elephant Trunk Technique: Early Results in Chronic Symptomatic Aortic Dissection Management. Ann Vasc Surg. 2019;57:244-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Leone A, Murana G, Di Marco L, Coppola G, Berardi M, Amodio C, Botta L, Pacini D. Current status in decision making to treat acute type A dissection: limited vs extended repair. The Bologna approach. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino). 2020;61:272-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |