Published online May 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i14.4586

Peer-review started: October 12, 2021

First decision: December 10, 2021

Revised: December 23, 2021

Accepted: March 25, 2022

Article in press: March 25, 2022

Published online: May 16, 2022

Processing time: 213 Days and 5.5 Hours

Sebaceous carcinoma (SC), a malignancy primarily characterized by aggressive growth, affects cutaneous tissues of the periocular region. Extraocular SC is extremely rare, especially in the extremities, as evidenced by only a handful of reported cases.

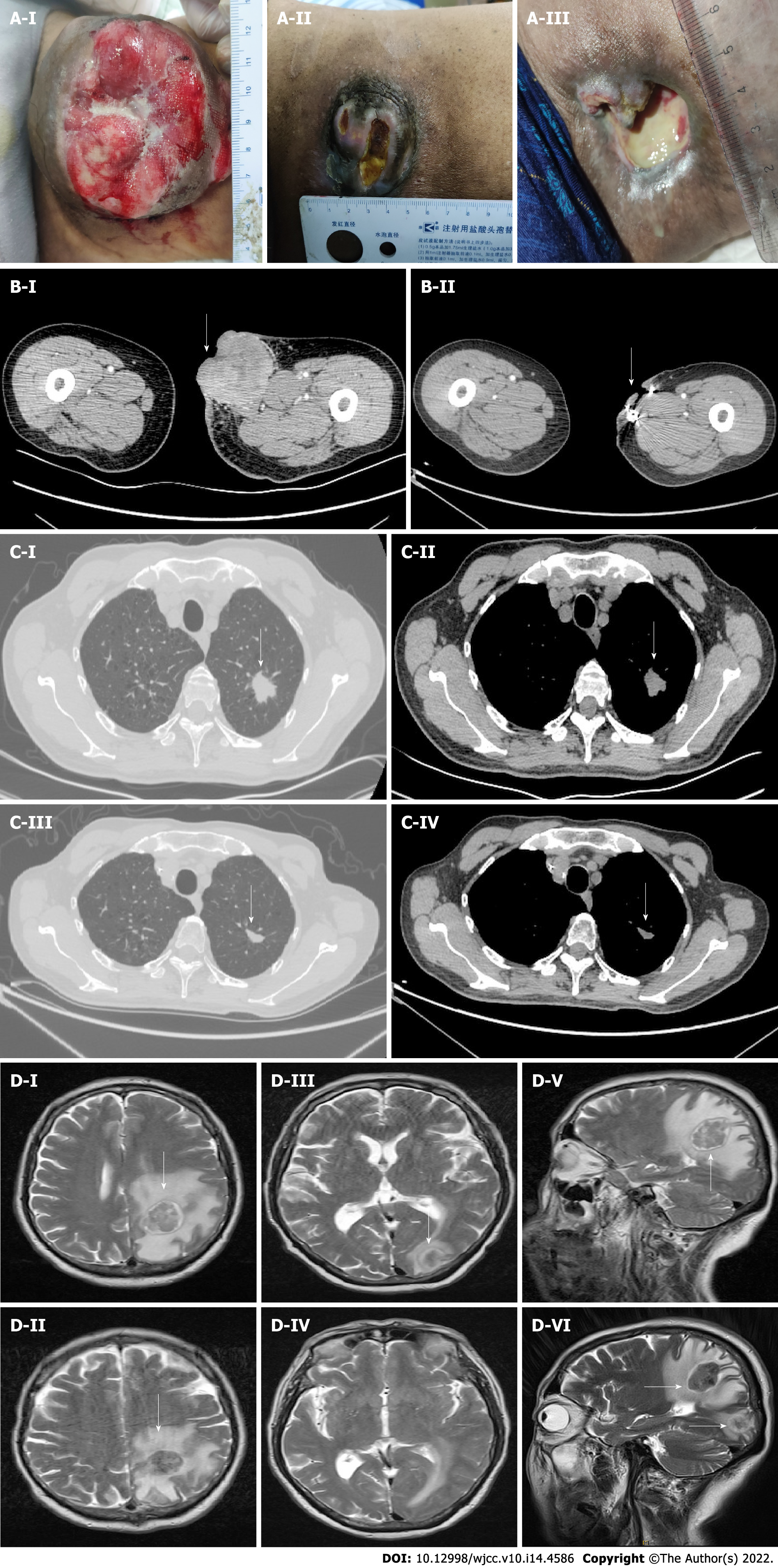

A 65-year-old man presented with a rapidly enlarging swelling on the left inner thigh, which was initially misdiagnosed as a subcutaneous abscess. The lesion had appeared two months prior to admission. Clinical examination revealed a cauliflower-like swollen content, with an ulcerated and infected mass located on his left thigh. At the same time, we observed solitary nodular lesions in his lungs and brain, with biopsy pathology of the lung lesions found to be consistent with the mass in the thigh. The patient received chemotherapy comprising cis-platinum with fluorouracil, followed by targeted therapy with anlotinib hydrochloride and chemotherapy with vinorelbine, implantation of iodine-125 seeds in the thigh and pulmonary tumor. The initial stage intervention achieved partial remission. The efficacy of maintenance treatment was evaluated as stable disease after the first 5 cycles; however, the patient developed a new brain lesion after the sixth cycle of treatment, which resulted in progressive disease and he received whole brain gamma knife radiotherapy.

We analyzed the clinical presentation, imaging features, pathology and treatment of a rare case of lung, brain and lymph node metastasis of SC located in the thigh. It is evident that cis-platinum combined with fluorouracil, vinorelbine combined with anlotinib hydrochloride may be an effective therapeutic regimen in advanced SC. However, brain metastatic lesions should receive early radiotherapy.

Core Tip: Sebaceous carcinoma (SC) is a rare malignant tumor of skin, mainly occurring in the head and neck, but rarely in the limbs. The diagnosis and treatment of SC remains unclear due to its rarity. Our patient presented with a skin mass with lung and brain lesions, which should be distinguished from skin metastasis of lung cancer. After comprehensive treatment, the patient achieved a good effect in the early stage, the later stage of the disease tended to be stable. It seems that cis-platinum combined with fluorouracil, vinorelbine combined with anlotinib hydrochloride may be an effective therapeutic regimen.

- Citation: Wei XL, Liu Q, Zeng QL, Zhou H. Primary or metastatic lung cancer? Sebaceous carcinoma of the thigh: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(14): 4586-4593

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i14/4586.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i14.4586

A sebaceous gland is a microscopic exocrine gland in the skin, which occurs between the hair follicles and the trichotricus erectus. It opens into a hair follicle and secretes an oily or waxy matter, called sebum, which lubricates the hair and skin in mammals. Sebaceous carcinoma (SC), which is characterized by aggressive growth, is a rare neoplasm that commonly arises in the eyelid and facial skin, and is extremely rare in other areas of the body[1]. Clinically, SC is typically asymptomatic, although it presents with yellow, red, or grayish-white domed nodules or plaques, accompanied by ulcers or crusts. The lack of specific clinical features often leads to delayed diagnosis or misdiagnosis. To date, diagnosis and treatment approaches for SC are not well studied due to the rarity of the tumor. Here, we present a case of lung, brain and lymph node metastasis from a thigh SC, and discuss the clinicopathological features, and treatment, with a brief review of relevant literature.

A 65-year-old man was admitted to the Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Affiliated Hospital of Chengdu University on March 18, 2020. His primary complaint was a lump on the left inner thigh, over the past 2 mo, and a 1-month-old pulmonary occupation. Two months prior to admission, the patient had developed a nodule on his left inner thigh, about the size of a broad bean, and was experiencing pain due to local compression, but with no discomfort, such as ulceration or suppuration. The patient had a cough but no chest pain, bloody sputum, headache or other discomfort.

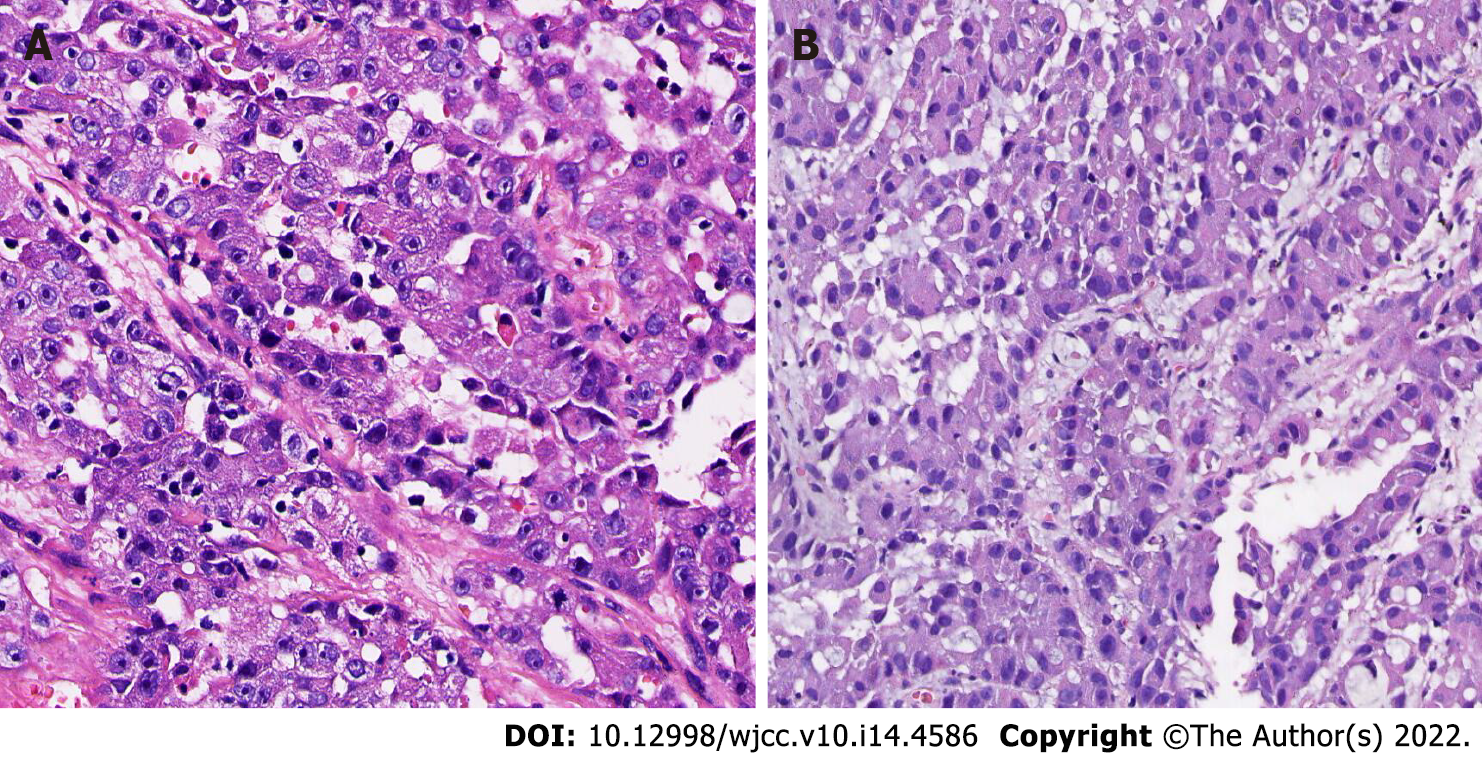

He had consulted a local hospital where they performed local incision and drainage as well as pathological biopsy, and his condition was considered to be “suppurative infection”. Results from pathological examinations suggested infiltration of malignant tumor with necrosis (Figure 1A), while immunohistochemical findings indicated Cytokeratin (CK) (+), Epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) (+), protein p63 (P63) (partial+), Thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) (-), chromogranin A (CgA) (-), S 100 (-), HMB45 (-), cell differentiation factor 34 (CD 34) and CD 31 (-), Ki- 67 (+, > 50%), in support of a poorly differentiated carcinoma, and SC was considered after exclusion of metastasis. A chest computed tomography (CT) scan revealed soft tissue shadows in the tip of the left upper lobe, about 19 mm × 23 mm × 21 mm, suggesting peripheral lung cancer. At the same time, the nodule in the patient’s inner thigh gradually grew, exhibiting local redness, swelling and bleeding.

Medical records revealed that the patient had neither a history of hypertension nor diabetes, but had an unexplained weight loss of 5 kg in the recent 2 mo. He had a 40-year history of tobacco smoking, although he had stopped in the 2 mo prior to admission. He also occasionally drank alcohol for over 40 years, although he was not addicted to it.

There was no pertinent family history.

A lump was found on the left inner thigh.

Routine blood tests were normal, including erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein. Both liver and kidney function were normal. CA19-9 and CA125 were significantly increased.

The patient underwent further examination to assess tumor metastasis. Analysis of plain and enhanced brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) images revealed a well-defined mass approximately 32 mm × 28 mm × 29 mm in size in the left parietal lobe. An enhanced chest CT scan showed a lobulated high-density shadow 23 mm × 21 mm × 25 mm in size in the upper lobe apex of the left lung, surrounded by spicules. Furthermore, systemic positron emission tomography-CT demonstrated the presence of a malignant lesion (peripheral lung cancer) at the tip of the upper lobe of the left lung, single brain metastasis in the left parietal lobe, and lymph node metastasis in the left inguinal region and the inner upper left thigh. No other abnormalities were observed.

Left thigh SC with lung, brain, and inguinal lymph node metastases.

The patient was administered cisplatin combined with fluorouracil for 6 cycles. In the first 4 cycles, the patient received intravenous infusion of 40 mg cisplatin from day 1 to day 3, intravenous injection of 250 mg fluorouracil from day 1 to day 4, and continuous intravenous pumping of 4000 mg fluorouracil from day 1 to day 4, once every 3 wk. Severe myelosuppression occurred after chemotherapy. Therefore, the subsequent two cycles of chemotherapy were adjusted as follows: Intravenous infusion of 50 mg cisplatin from day 1 to day 2, intravenous injection of 250 mg fluorouracil from day 1 to day 4, continuous intravenous pumping of 4000 mg fluorouracil from day 1 to day 4, once every three weeks, with implantation of iodine-125 seeds in the thigh and pulmonary tumor. We recommended brain radiotherapy, and the patient declined. Thereafter, the patient was sustained on a maintenance treatment comprising targeted therapy with anlotinib hydrochloride combined with vinorelbine adjuvant chemotherapy for 6 cycles. The dose of anlotinib hydrochloride was 12 mg once a day, taken orally before breakfast. This medication was continued for 2 wk and withdrawn for 1 wk, i.e., the course of treatment was 3 wk (21 d). Vinorelbine treatment was administered as follows: In the first cycle, 80 mg vinorelbine tartrate soft capsule was given orally on the first day, and 100 mg vinorelbine tartrate soft capsule was administered orally on the eighth day. From the second to the sixth cycles, 100 mg vinorelbine tartrate soft capsule was given orally on the first day and on the eighth day, once every 3 wk.

After the first stage treatment, we observed a significant reduction in the nodule on the medial side of the left thigh, as well as marked improvement in local ulceration and bleeding as well as a reduction in lung and brain metastases. After 6 cycles of early-stage chemotherapy, the patient achieved partial remission (PR). There were no significant adverse events. After the first 5 cycles of maintenance treatment, efficacy of this maintenance treatment was evaluated as stable disease (SD), and the lung and thigh lesions continued to shrink. However, the patient developed a new brain lesion after the sixth cycle of treatment (Figure 2), which resulted in progressive disease (PD) on comprehensive efficacy evaluation, and he received whole brain gamma knife radiotherapy at a regular dose, and continued with anlotinib combined with vinorelbine treatment. We will continue to follow his condition.

Radiological evaluation of the brain and chest after maintenance treatment confirmed the following: Chest CT scan revealed a lobulated high-density shadow 11 mm × 17 mm × 13 mm in size in the upper lobe apex of the left lung, surrounded by spicules, and focal emphysema. Brain MRI revealed an irregular solid lesion (25 mm × 22 mm) in the left parietal lobe, and an irregular solid lesion (18 mm × 15 mm) in the left occipital lobe. The edges of the lesions seemed to be surrounded by a capsule.

SC is a rare malignant tumor that originates from adnexal skin structures. This rare and potentially aggressive sebaceous gland derived malignancy was first described in the salivary glands by Rauch and Masshoff[2]. The typical clinical manifestations of SC are painless skin nodules, with slow growth, or diffuse thickening of the skin and an irregular mass, and often involve the subcutaneous tissue, or distant metastasis, which can easily be misdiagnosed as benign disease and delayed diagnosis, thereby requiring differentiation from cutaneous inflammation, sebaceous cyst and cutaneous malignant tumor[3,4]. Although SC often occurs in the head and neck, about 75% of adenocarcinomas in all cases are found around the orbit, especially the eyelid. Notably, only about 25% of these cases originate from the sebaceous glands outside the orbit, such as the neck, scalp, trunk, limbs, and the reproductive system. SC is usually divided into the eye and extraocular areas, and its onset is predominantly in people aged between 60 to 70 years old. Previous studies have found no evidence of significant differences in its incidence between men and women, although it is more common in Asian populations[5,6]. Extraocular SCs are extremely rare skin cancers, exhibiting diverse clinical and histopathological manifestations, which makes diagnosis difficult, thereby increasing the rate of misdiagnosis and missed diagnosis. In the present study, our patient was a 65-year-old man, and his age was within the average age of people expected to be diagnosed with SC. However, he presented with an extraocular neoplasm at an atypical location, the thigh. Given that the neoplasm did not cause pain or swelling, it was initially misdiagnosed as a subcutaneous abscess and it was not clear whether it could be considered as skin cancer lung metastasis or lung cancer skin metastasis.

SC has a varied pattern of histopathological manifestations. Microscopically, tumor cells show lobulated or papillary growth, and are arranged into a number of nests or sheets of different sizes by the fibrous stroma. In fact, these present an invasive growth pattern, with varying degrees of pleomorphism and atypia, as well as common cell necrosis and fibrosis. Notably, SC with prevalent cellular pleomorphism and cytologic atypia can exhibit poorly differentiated squamous cell sample sebaceous gland cancer alien, owing to differences in the degree of differentiation, and these are characterized by obvious squamous metaplasia, as evidenced by keratin pearls. Alternatively, they may show basal cell sebaceous gland cancer alien, with tumor tissue invading surrounding tissues and cells is less cytoplasm of basaloid cells, arranged in a fence surrounding the form, the center can form “acne” necrosis, nuclear pleomorphism, and prominent nucleoli. Therefore, clinicians can employ immunohistochemical studies using oil red-O stain, fat stain, EMA, cytokeratin, CAM 5.2, or BRST-1 to differentiate it from mucoepidermoid carcinoma, poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma and metastatic clear cell renal carcinoma[7-10]. In the present case, immunohistochemical analysis revealed that both the primary SC and pulmonary metastasis were positive for EMA, Ki-67 but negative for TTF-1, whereas pulmonary metastasis was positive for CAM 5.2 but negative for P63, Napsin-A, and CEA. Based on these findings, we diagnosed the pulmonary disease as pulmonary metastasis from SC.

SC can be part of Muir-Torre syndrome, an autosomal dominant genetic syndrome characterized by the presence of at least one sebaceous adenoma and internal malignancy. Colorectal cancer is the most common internal malignancy[11]. As the patient in the present study exhibited abnormalities in many markers, such as CA19-9 and CA125, gastroscopy was performed to ascertain intestinal polyps. Although pathological biopsy revealed benign lesions, we could not rule out the possibility of them turning into malignant lesions during disease progression. Therefore, we recommend regular follow-up gastroscopy during later stages, as well as health screening of family members.

Currently, surgical resection of early and low-grade tumors are the key treatment strategies for SC, although they are associated with high local recurrence rates after excision[12]. For patients with high-grade and advanced tumors, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, local treatment, and other comprehensive treatment measures are recommended. Anti-angiogenesis and blocking of certain inflammatory pathways are expected to become new treatment targets[13,14]. Previous evidence has recently demonstrated the efficacy of platinum in combination with immunotherapy for some patients with postoperative recurrence, such as Programmed death-1 (PD- 1) or Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L 1) inhibitors during SC treatment[15,16]. However, these treatments are mainly for ocular SC, while treatment for extraocular SC is not well studied. This patient had a short disease course, but once confirmed, he presented with local lymph node, lung and brain metastases, making it impossible to perform early radical surgery. Therefore, we chose comprehensive treatment. Fortunately, the therapeutic effect of cisplatin combined with fluorouracil in the early stage was good. Although severe myelosuppression occurred, the patient’s condition significantly improved. During chemotherapy, the patient received iodine-125 seeds implantation in the thigh and lung lesions, and the final therapeutic outcome was designated as PR. For maintenance treatment, targeted anlotinib therapy combined with vinorelbine tartrate soft capsule adjuvant chemotherapy was administered. The response to chemotherapy and targeted therapy was SD in the first 5 cycles. However, the patient developed new brain metastases due to delayed brain radiotherapy after the 6th cycle of therapy. The patient is currently continuing to receive anlotinib hydrochloride combined with vinorelbine maintenance treatment. Our treatment significantly reduced the primary lesion in the leg and distant metastases in the lung and lymph node of the patient, indicating that chemoradiotherapy, targeted therapy and early brain radiotherapy may be efficacious in treating lung and brain metastases from thigh SC with well tolerated toxicity. The subsequent outcome of the brain lesions still needs further observation.

SC is a very rare and aggressive malignant tumor. Here, we treated a case of SC originating from the lower extremity, which had initially been misdiagnosed as an abscess with incision and drainage, and obtained a relatively satisfactory outcome. In clinical practice, it is necessary to pay attention to the differential diagnosis in order to avoid misdiagnosis and missed diagnosis. Although, there is currently no better treatment, it is clear that early and accurate diagnosis and removal of the lesion could benefit these patients. Patients with brain metastases should receive early radiotherapy. The lack of in-depth experience necessitates further exploration of novel and effective treatment strategies for sebaceous adenocarcinoma, including radiotherapy and targeted therapy.

The authors thank the patient for permitting them to use his data to complete this article.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Nyamuryekung'e MK, Tanzania; Wang J, China S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Dasgupta T, Wilson LD, Yu JB. A retrospective review of 1349 cases of sebaceous carcinoma. Cancer. 2009;115:158-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rauch S, Masshoff W. [Sialoma resembling sebaceous gland]. Frankf Z Pathol. 1959;69:513-525. [PubMed] |

| 3. | C S, P M, J SB, J B. Sebaceous carcinoma of the chest wall: A case report. Radiol Case Rep. 2021;16:1870-1873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lee DW, Kwak SH, Kim JH, Byeon JY, Lee HJ, Choi HJ. Sebaceous carcinoma arising from sebaceoma. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2021;22:126-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Khmou M, Laadam K, Cherradi N. Parotid gland, an exceptional localization of sebaceous carcinoma: case report. BMC Clin Pathol. 2016;16:10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Walsh MD, Jayasekara H, Huang A, Winship IM, Buchanan DD. Clinico-pathological predictors of mismatch repair deficiency in sebaceous neoplasia: A large case series from a single Australian private pathology service. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60:126-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Marnouche el A, Maghous A, Kadiri S, Berhili S, Touil A, Kettani F, Majjaoui S, Elkacemi H, Kebdani T, Benjaafar N. Sebaceous carcinoma of the parotid gland: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2016;10:174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Park H, Choi SG. Primary sebaceous carcinoma of lacrimal gland: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases. 2018;6:1194-1198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cicinelli MV, Kaliki S. Ocular sebaceous gland carcinoma: an update of the literature. Int Ophthalmol. 2019;39:1187-1197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kawagishi S, Kanzaki R, Taniguchi S, Kimura K, Kimura T, Takabatake H, Morii E, Inoue M, Shintani Y. A case of repeat resection for recurrent pulmonary metastasis from sebaceous gland carcinoma. Surg Case Rep. 2020;6:206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chakravarti N, El-Naggar AK, Lotan R, Anderson J, Diwan AH, Saadati HG, Diba R, Prieto VG, Esmaeli B. Expression of retinoid receptors in sebaceous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:10-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Xu Y, Li F, Jia R, Fan X. Updates on the clinical diagnosis and management of ocular sebaceous carcinoma: a brief review of the literature. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:3713-3720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Erovic BM, Al Habeeb A, Harris L, Goldstein DP, Kim D, Ghazarian D, Irish JC. Identification of novel target proteins in sebaceous gland carcinoma. Head Neck. 2013;35:642-648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sa HS, Tetzlaff MT, Esmaeli B. Predictors of Local Recurrence for Eyelid Sebaceous Carcinoma: Questionable Value of Routine Conjunctival Map Biopsies for Detection of Pagetoid Spread. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;35:419-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kodali S, Tipirneni E, Gibson PC, Cook D, Verschraegen C, Lane KA. Carboplatin and Pembrolizumab Chemoimmunotherapy Achieves Remission in Recurrent, Metastatic Sebaceous Carcinoma. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;34:e149-e151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bowen RC, Lawson BM, Jody NM, Potter HD, Lucarelli MJ. The Programmed Death Pathway in Ocular Adnexal Sebaceous Carcinoma. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;36:74-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |