Published online Jun 25, 2025. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v14.i2.103027

Revised: February 23, 2025

Accepted: March 20, 2025

Published online: June 25, 2025

Processing time: 155 Days and 3.4 Hours

Hydatid cyst disease, caused by Echinococcus granulosus, primarily affects the liver and lungs, but it can also develop in rare locations such as the kidneys, thyroid, subcutaneous tissues, bones, and the mediastinum. These atypical presentations often pose diagnostic challenges, as they can mimic benign and malignant pathologies, leading to potential misdiagnoses and inappropriate treatments. Early and accurate detection of hydatid cysts in uncommon sites is crucial for optimal patient management.

This case report series presents five patients with hydatid cysts located in atypical anatomical regions: The kidney, lumbar subcutaneous tissue, gluteal soft tissue, posterior mediastinum, and thyroid gland. The patients exhibited diverse clinical symptoms, including hematuria, palpable masses, localized pain, and chronic cough. Diagnosis was confirmed through a combination of imaging techniques-ultrasound, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging-along with serological testing. All cases were managed with antiparasitic therapy (alben

Recognizing hydatid cysts in atypical locations is essential to avoid misdiagnosis and ensure appropriate treatment strategies. Radiological imaging plays a key role in distinguishing hydatid cysts from other cystic and neoplastic conditions, while serological tests can aid in confirmation, particularly in endemic regions. A multidisciplinary approach, integrating radiology, clinical evaluation, and sur

Core Tip: Although the liver and lungs are responsible for 65% and 25% of Hydatid cyst illness, cysts can also occasionally develop in unusual locations like the kidneys, thyroid, bones, and subcutaneous tissue. By compressing the afflicted organs, hydatid illness can result in cysts, abscesses, and empyema. Major repercussions may ensue if it is not identified in a timely manner; if the cyst ruptures, it may cause disastrous results including anaphylaxis. A multidisciplinary approach directed by radiological data enables improved diagnosis, quicker treatment, and better patient outcomes, according to recent research and case studies.

- Citation: Celik AS, Yosunkaya H, Yayilkan Ozyilmaz A, Memis KB, Aydin S. Echinococcus granulosus in atypical localizations: Five case reports. World J Nephrol 2025; 14(2): 103027

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-6124/full/v14/i2/103027.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5527/wjn.v14.i2.103027

Hydatid cyst disease is an endemic zoonosis caused by the parasite Echinococcus granulosus, which typically affects the liver and lungs[1,2]. This disease is transmitted to humans by contaminated food, where parasite eggs are disseminated through sick dogs' excrement. After entering the host's gastrointestinal tract, the parasite spreads to several organs, where it creates slow-growing, generally asymptomatic cysts. Hydatid disease can cause cysts, abscesses, and empyema by compressing the affected organs. If not detected early, it can lead to major consequences; in the event of cyst rupture, it can result in catastrophic outcomes such as anaphylaxis.

The liver accounts for 65% of the disease and the lungs for 25%; nevertheless, cysts can occasionally form in odd places such as the kidneys, thyroid, bones, and subcutaneous tissue[1]. It has an uncommon effect on the skeletal system, occurring in about 0.5-2% of instances, with the spine accounting for half of these occurrences[3]. Studies indicate that extrapulmonary hydatid cysts account for approximately 7.4% to 10.5% of intrathoracic hydatid cysts[4].

Hydatid cysts are extremely rare in subcutaneous tissues; in endemic areas, the frequency is approximately 2.3%[5]. Furthermore, some case reports claim that hydatid cysts do not form in keratinized tissues like nails and hair[6,7].

Hydatid disease has the potential to affect the entire body, as shown in Table 1[8]. This case series includes computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) images of three separate hydatid cysts that affect anatomical areas other than the liver and lungs.

Case 1: A 45-year-old woman presented with right flank pain and hematuria.

Case 2: A 43-year-old woman reported a palpable mass in the lumbar region.

Case 3: A 39-year-old woman complained of swelling and pain in the right gluteal region.

Case 4: A 77-year-old woman presented with a persistent cough.

Case 5: A 41-year-old woman was referred for evaluation of a swelling in the neck.

Case 1: The patient had no known comorbidities. She experienced persistent right flank pain and noticed blood in her urine.

Case 2: The patient had no prior known illnesses. She noticed a painless mass in her lumbar region, which later became tender.

Case 3: The patient had a prior history of liver hydatid cyst and lived with two dogs. She developed new symptoms of localized pain and swelling in the gluteal region.

Case 4: The patient had hypertension, diabetes, and a history of cardiac bypass surgery. She experienced a persistent cough without fever or hemoptysis.

Case 5: The patient had no previous illnesses but had noticed a swelling in the left side of her neck.

Case 1: No significant medical history.

Case 2: No significant medical history.

Case 3: Previously diagnosed with a hydatid cyst in the liver.

Case 4: History of hypertension, diabetes, and cardiac bypass surgery.

Case 5: No significant past medical history.

Case 1: No relevant personal or family history.

Case 2: No relevant personal or family history.

Case 3: Frequent contact with dogs at home.

Case 4: No relevant personal or family history.

Case 5: History of dog grooming.

Case 1: Tenderness in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen.

Case 2: Well-defined, firm, non-mobile mass in the lumbar region.

Case 3: Localized swelling and tenderness in the right gluteal region.

Case 4: No abnormal lung sounds.

Case 5: Painless, mobile, well-defined nodule in the left thyroid lobe.

Case 1: Urine microscopy showed mucus, epithelial cells, and erythrocytes.

Case 2: Routine blood parameters were normal; serology test positive for hydatid cyst.

Case 3: Serology test positive for hydatid cyst.

Case 4: Serology test positive for hydatid cyst.

Case 5: Thyroid function tests were normal; hydatid hemagglutination test positive.

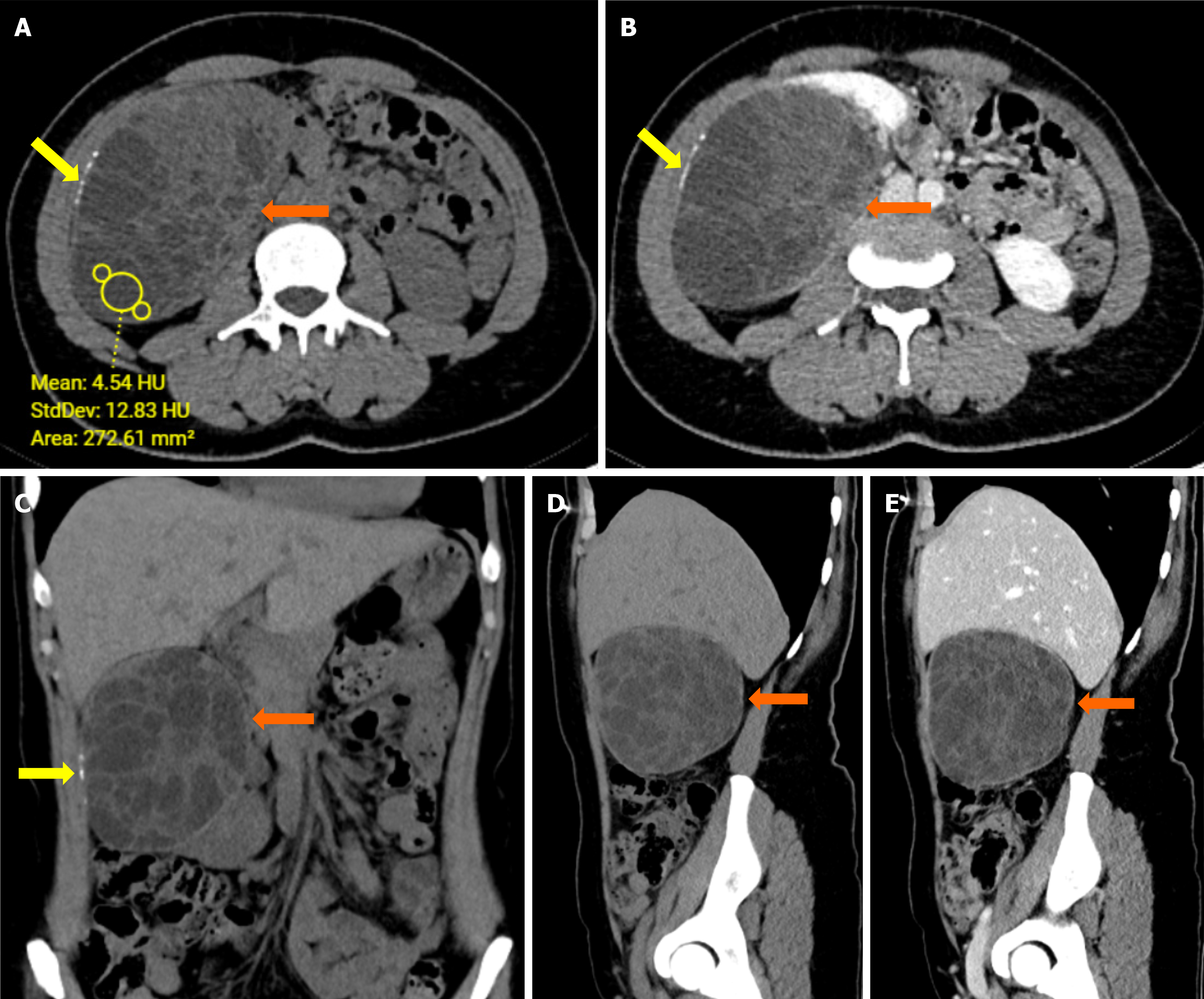

Case 1: Renal ultrasound (US) and CT showed a multiloculated cystic lesion with septa and calcifications (Figure 1).

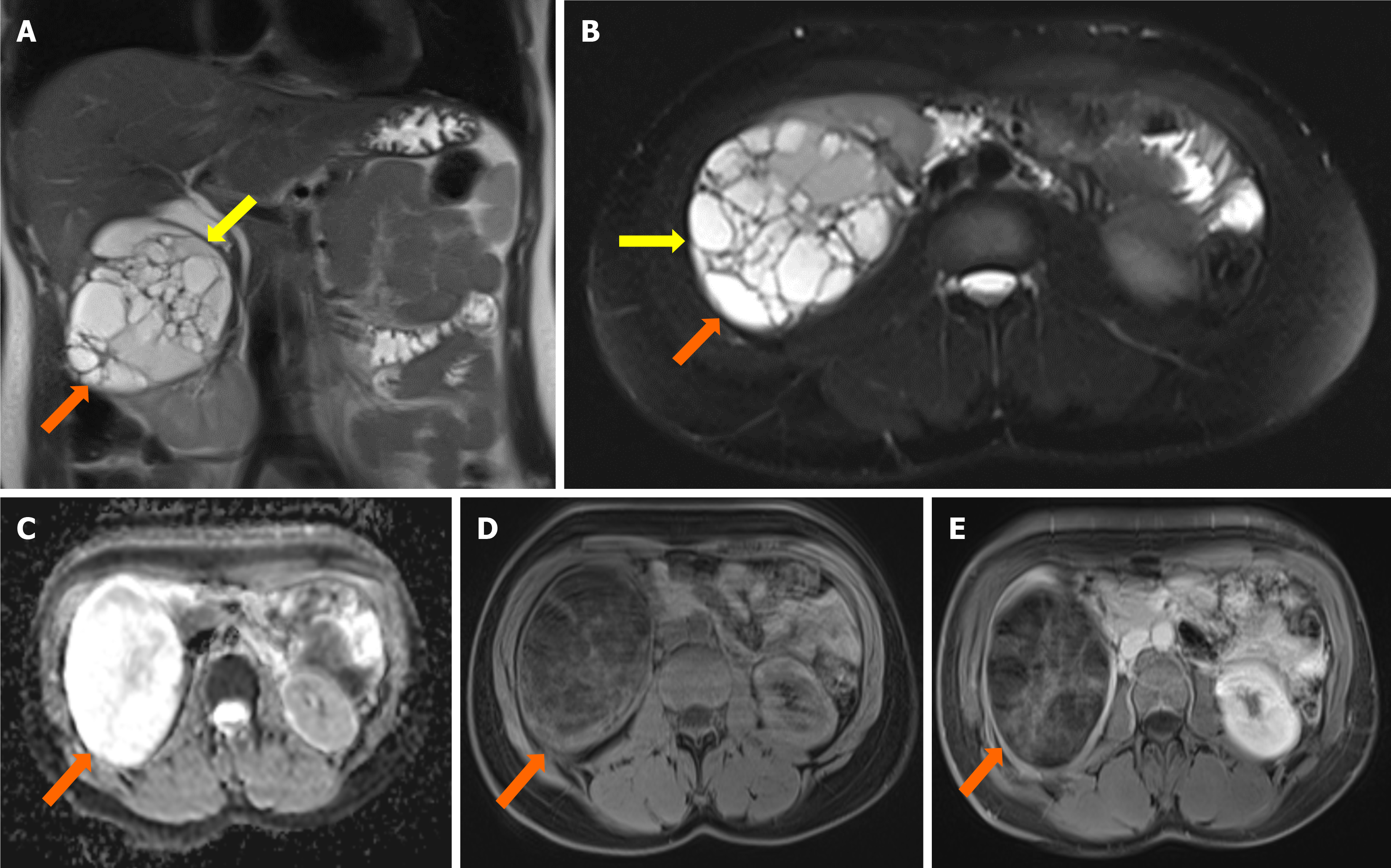

Case 2: Ultrasonography and MRI revealed multiloculated cystic lesions with mural and septal enhancements (Figure 2).

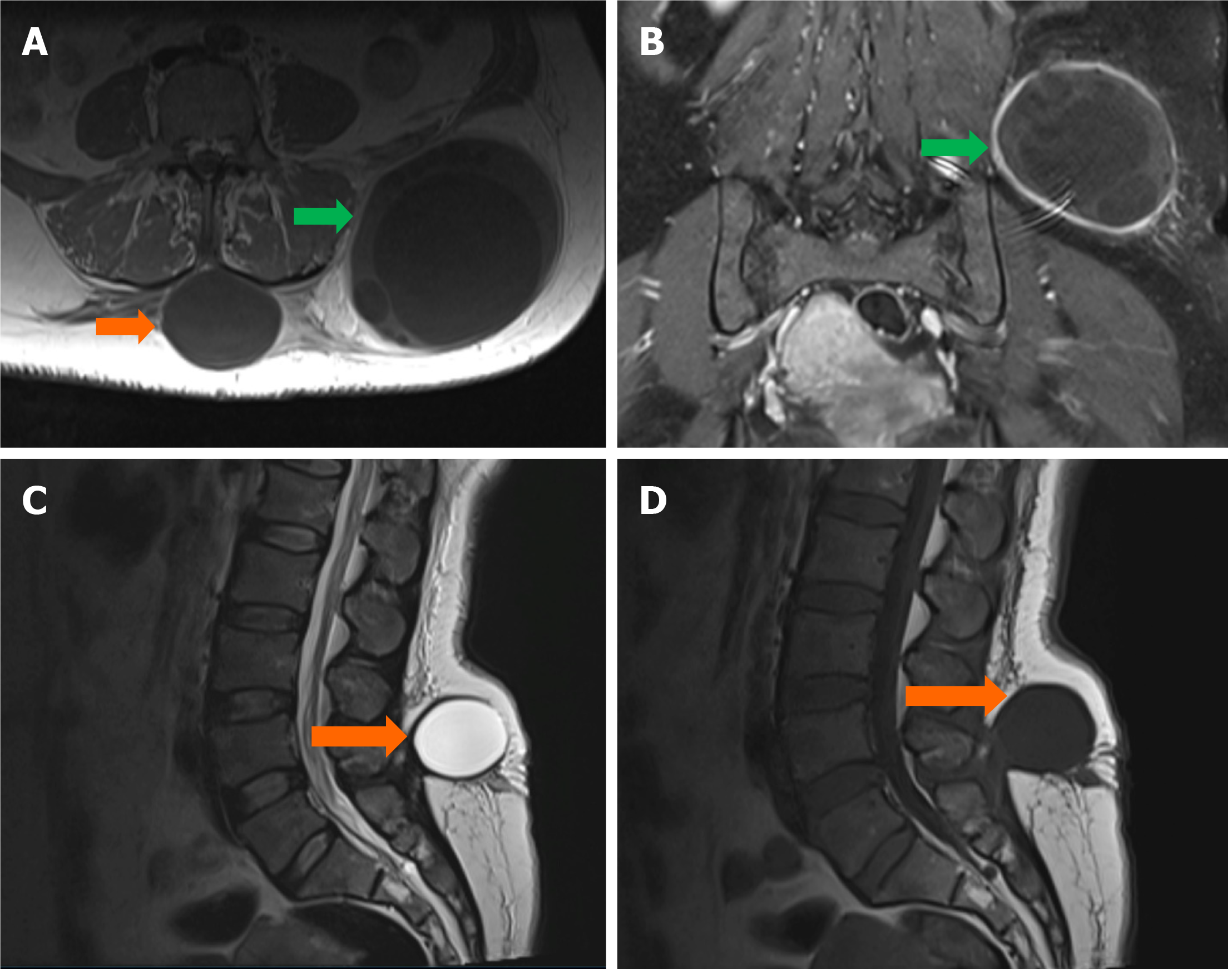

Case 3: CT showed hydatid cysts in the liver, lung, bone, and soft tissue (Figure 3).

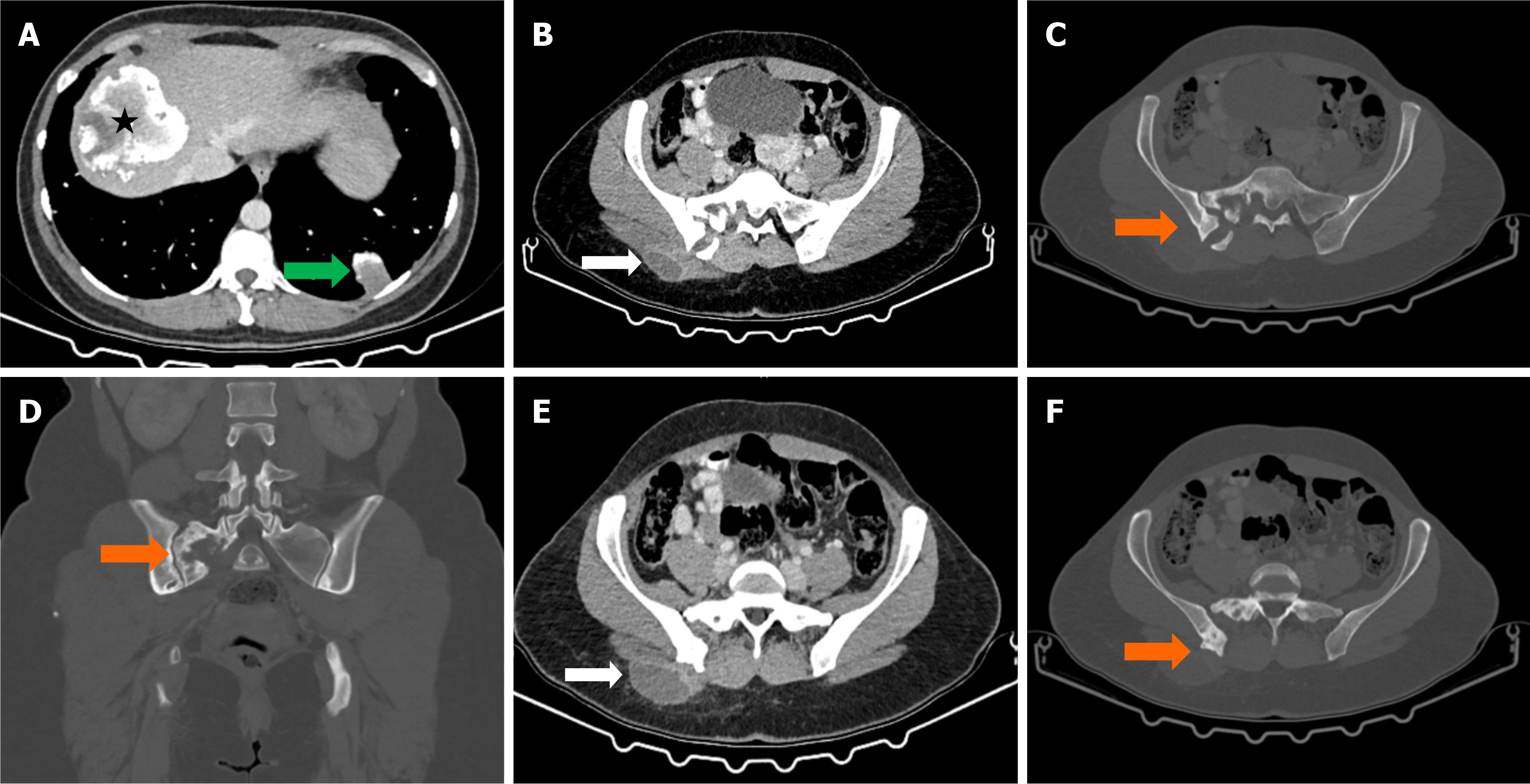

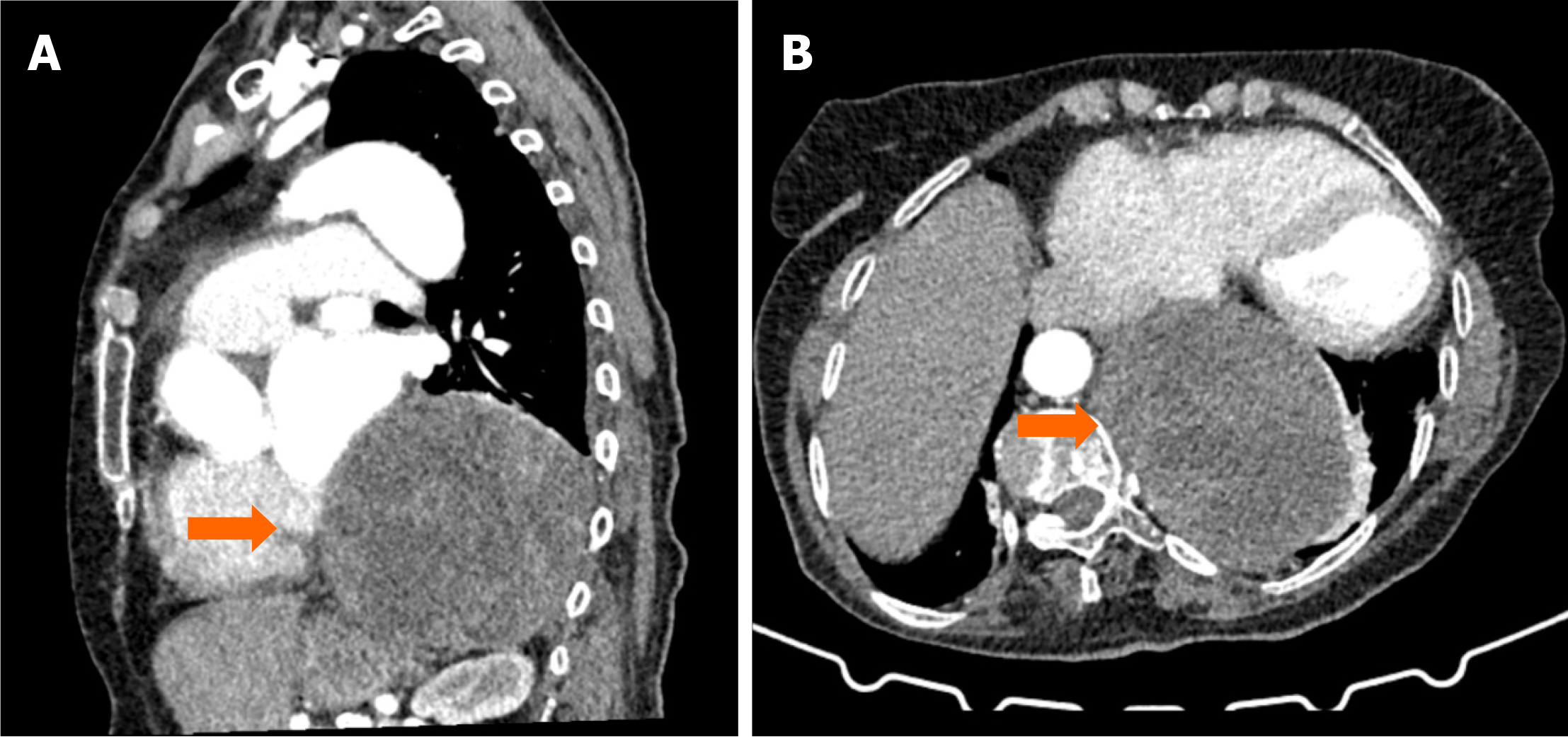

Case 4: Thoracic CT revealed a cystic lesion in the posterior mediastinum (Figures 4 and 5).

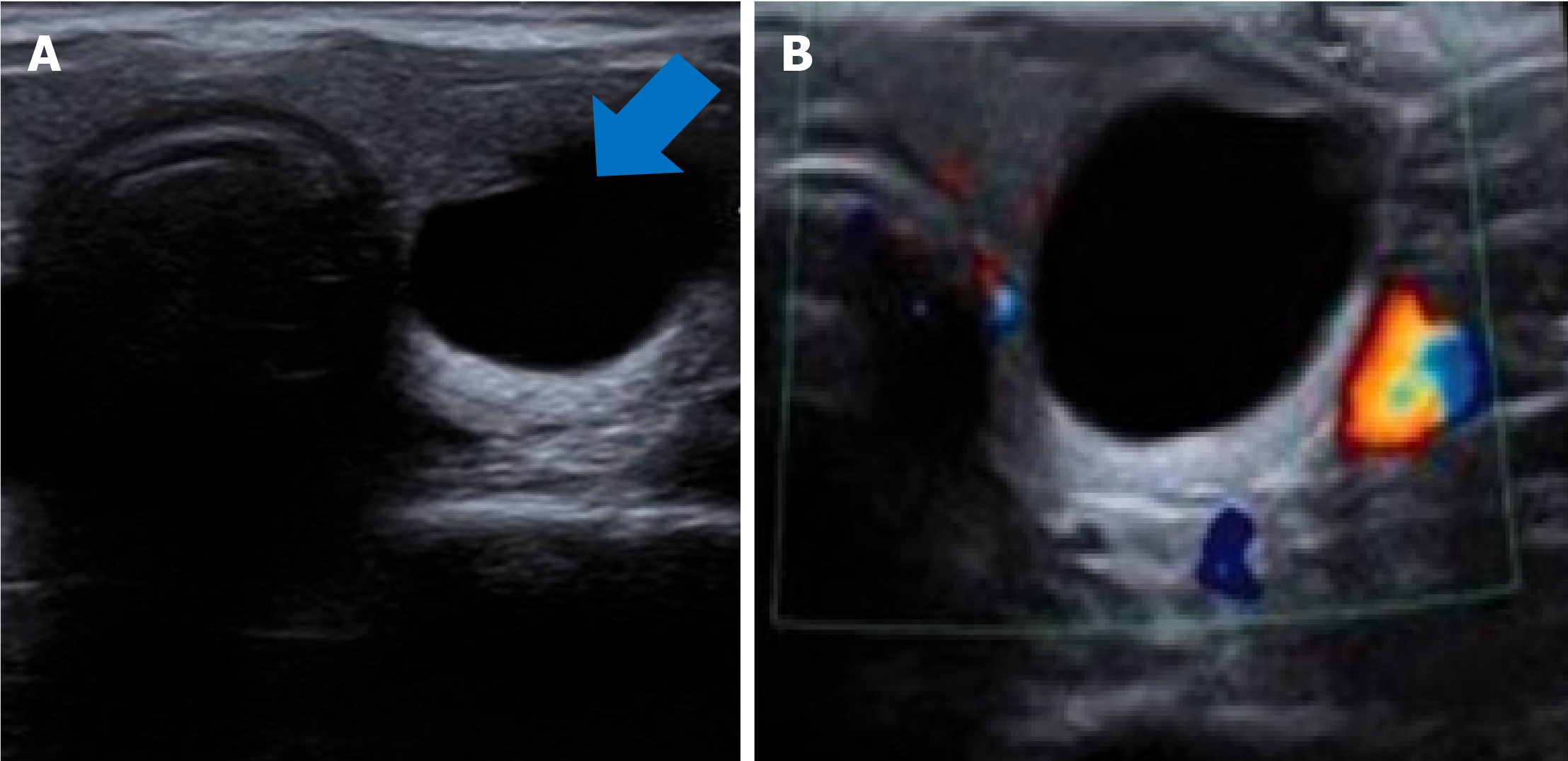

Case 5: US showed a 15-mm anechoic cystic lesion in the thyroid (Figure 6).

Case 1: Renal hydatid cyst.

Case 2: Hydatid cyst in the subcutaneous lumbar region.

Case 3: Hydatid cysts in liver, lung, bone, and soft tissue.

Case 4: Hydatid cyst in the posterior mediastinum.

Case 5: Hydatid cyst of the thyroid gland.

Case 1: Antiparasitic therapy (albendazole) and surgical intervention.

Case 2: Antiparasitic therapy (albendazole) and surgical excision.

Case 3: Antiparasitic therapy (albendazole) and surgical intervention for gluteal and bone lesions.

Case 4: Antiparasitic therapy (albendazole) and surgical excision.

Case 5: Total thyroidectomy instead of fine-needle aspiration biopsy.

Case 1: Follow-up imaging showed no recurrence.

Case 2: Postoperative follow-up showed complete resolution of symptoms with no recurrence.

Case 3: Follow-up imaging confirmed stability of liver and lung cysts.

Case 4: The patient recovered well with no recurrence on follow-up imaging.

Case 5: Histopathological examination confirmed the diagnosis, and no recurrence was noted during follow-up.

Hydatid cyst is a zoonotic infection caused by Echinococcus granulosus or, less frequently, Echinococcus multilocularis. It is typically transmitted to humans via water or food contaminated with infected dog feces. The parasite forms cysts in the human body, disrupting the function of various organs, especially the liver and lungs. When cysts form in the liver, patients frequently experience abdominal pain, a sense of fullness, and, in rare cases, jaundice. Lung cysts may cause cough, hemoptysis and shortness of breath[1]. In rare cases, other organs such as the brain, kidneys, spleen, and subcutaneous tissues may become involved, resulting in more complex clinical presentations. For example, spinal hydatid cysts can cause back and lower back pain, while cysts in the intrathoracic region can result in more complex and difficult clinical courses[4].

The prevalence of hydatid disease varies by geographical region and public health measures. Globally, the prevalence of this disease in endemic areas ranges between 1 and 200 cases per 100000 people. The Mediterranean countries, the Middle East, South America, and parts of Asia and Africa are among those hardest hits[6]. In Turkey, hydatid cyst illness is a major public health issue. According to research, the overall prevalence in Turkey ranges from 6 to 30 cases per 100000 individuals, with rates exceeding 50 cases per 100000 in some rural areas where livestock rearing is common[2]. Uncontrolled dog populations and poor hygiene standards contribute to the disease's broad prevalence in these areas[5].

Hydatid disease is diagnosed using a comprehensive approach that includes clinical history, physical examination, serologic laboratory testing, and radiologic imaging[1]. The detection of germinal vesicles on US, CT, or MRI is critical for diagnosis[1,9].

Hydatid cysts can be categorized radiologically into four forms: Simple cyst, calcified cyst, complicated cyst, and cyst with matrix and daughter vesicles[2].

Simple cysts show up as well-defined anechoic masses on US scans, with or without septa and hydatid sand, creating tiny echogenic focus. It is thought to be diagnostic when daughter vesicles, matrix, or septa are present inside a cystic cavity. Dead, calcified cysts are indicated by posterior shadowing, whereas complex cysts may exhibit an undulating membrane as a result of the endocyst and pericyst separating[10]. Cysts containing daughter vesicles show up as irregular structures on CT imaging, while simple cysts show up as a peripherally contrasted hypodense mass lesion. Round calcified areas are the hallmark of calcified cysts, but membrane fluctuations or ruptures may be seen in complex cysts[10,11]. Additional information is provided by MRI; simple cysts show up as hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging and hypointene on T1-weighted images. After contrast administration, septa and cyst walls show enhanced thickness, and daughter cysts can be distinguished by their unique signal characteristics[10-12].

Hydatid cysts can be challenging to diagnose because their imaging features often overlap with other cystic and neoplastic conditions, including malignancies. There are many studies in the current literature on the diagnosis of hydatid cysts using radiological diagnostic tools[13,14].

In the kidneys, they may resemble multicystic RCC or cystic nephroma due to their multiloculated structure, irregular septa, and peripheral calcifications. Similarly, spinal or soft tissue hydatid cysts can be mistaken for cystic schwannomas, metastatic cystic lesions, or pyogenic abscesses. In the thyroid, they may look similar to benign colloid cysts or cystic papillary thyroid carcinoma. Differentiating hydatid cysts from these conditions is crucial, as a misdiagnosis could lead to unnecessary surgeries or inappropriate cancer treatments.

Imaging plays a key role in distinguishing hydatid cysts from malignant lesions. Features like floating membranes, daughter cysts, and internal septations are strong indicators of hydatid disease and are rarely seen in malignancies. On the other hand, malignant cysts typically have solid enhancing components, irregular thickened walls, and show invasive growth into surrounding tissues. Another helpful clue is rim calcification—while hydatid cysts tend to have smooth peripheral calcifications without aggressive destruction, malignant lesions often show irregular, infiltrative calcifications. Diffusion-weighted MRI and contrast-enhanced CT also help differentiate these lesions; hydatid cysts usually appear bright on T2-weighted images and show minimal enhancement, whereas malignant cysts often display heterogeneous enhancement due to their vascular nature.

Serological tests such as ELISA and Western blot for Echinococcus granulosus can provide additional confirmation, especially in endemic regions. However, a negative result does not always rule out the disease, as some cases may be seronegative. Therefore, an accurate diagnosis requires a multidisciplinary approach, integrating radiologic, serologic, and clinical findings to ensure proper management and avoid misdiagnosis.

Medical treatment is an important part of managing hydatid cysts and can be used in conjunction with surgery or on its own. Antiparasitic medications like albendazole and mebendazole are used to decrease cysts and reduce parasite activity. Albendazole is commonly supplied at a dose of 10-15 mg/kg per day to adults, divided into two doses in the morning and evening. The recommended treatment length is 28 days, followed by a 14-day respite, and this cycle can be repeated 2-4 times depending on the patient's condition and cyst size[9]. Mebendazole is another alternative, though less usually used, at a daily dose of 40-50 mg/kg, with therapy lasting several months. Liver function and complete blood count should be checked during treatment to avoid possible adverse effects of medical therapy, such as liver function abnormalities, gastrointestinal upset and, in rare cases, bone marrow suppression[6].

There are many studies in the literature regarding treatment protocols and follow-up of hydatid cysts[15,16]. Surgical treatment is recommended for large, symptomatic, or complicated hydatid cysts. The main surgical approaches include total cystectomy, partial cystectomy, and capitonnage. Total cystectomy involves complete cyst removal, while partial cystectomy preserves part of the cyst wall. Capitonnage is performed by closing the cavity after cyst evacuation.

The most significant risk during surgery is cyst rupture, which can lead to the dissemination of parasitic material, anaphylactic shock, and secondary cyst formation[2]. To minimize this risk, 20% hypertonic saline or povidone-iodine solution is used to sterilize the surgical field. Despite surgical removal, recurrence rates range from 10% to 30%, necessitating long-term follow-up. Postoperative albendazole therapy is recommended to eliminate any remaining microscopic parasites.

For patients who are not suitable candidates for surgery or are at high surgical risk, percutaneous aspiration, injection, and reaspiration (PAIR) is a minimally invasive alternative. This procedure involves aspirating the cyst content under US or CT guidance, injecting a scolicidal agent (e.g., 95% ethanol or 20% hypertonic saline), and then reaspirating the fluid. PAIR is particularly effective for hepatic and renal cysts, especially those smaller than 5 cm, and has the advantage of reducing surgical complications. However, due to the risk of cyst rupture and anaphylaxis, PAIR should only be performed in experienced centers.

Hydatid disease requires long-term monitoring due to the risk of recurrence. Patients should be followed up using clinical assessment, serological tests, and imaging techniques (US, CT, MRI). Patients receiving medical treatment should be evaluated every 6 to 12 months, while post-surgical patients require follow-ups every 3 to 6 months in the first year and annually thereafter. PAIR-treated patients should undergo US evaluations at 1, 3, 6, and 12. months post-procedure. Treatment success is defined by cyst shrinkage, calcification, or complete resolution, with recurrence rates ranging from 10% to 30%.

Hydatid disease causes severe and widespread liver damage, sometimes requiring liver transplantation. This is especially important when the parasite severely inhibits liver function, causes organ failure, or has multiple cysts that cannot be treated surgically[10]. A liver transplant may also be required when the liver cannot function properly or previous surgeries have failed. Interventional treatment options might be viewed as an alternate or complementary approach to surgery. Minimally invasive treatments for hydatid cysts include percutaneous aspiration, drainage, and procedures using sclerosing agents. These operations involve aspirating fluid from the cyst with a needle under US or CT guidance, followed by injecting a sclerosing chemical to treat the cyst wall. Although percutaneous cyst resistance with albendazole treatment is a long-term treatment, especially in patients who cannot be operated on, it is sometimes the only solution to protect patients from rupture, reduce the risk of reinfection and relieve pressure symptoms. This method reduces cyst size while also neutralizing parasites. Interventional procedures are especially useful for patients who are at high surgical risk or who are not eligible for surgery, as they provide a faster recovery time[2,6].

Hydatid cysts are most typically found in the liver and lungs, although they can also form in other unusual places on the body. Atypical sites include the kidneys, spleen, brain, spine, subcutaneous tissue, and intrathoracic areas. Renal cysts can induce flank pain and urine symptoms, whereas brain cysts may cause headaches, seizures, and other neurological symptoms[8]. Spinal hydatid cysts can cause persistent discomfort, neurological impairments, and paralysis[3,7]. Subcutaneous tissue cysts generally cause swelling and pain[5].

Atypical sites can complicate diagnosis and therapy because these cysts frequently mirror other diseases, increasing the risk of misdiagnosis. Detailed imaging and a multidisciplinary approach are required for precise diagnosis and treatment planning. The existence of cysts in unusual sites influences the selection and execution of surgical and medicinal treatment, necessitating increased attention. This article focuses on the careful evaluation of cases with unusual localizations and emphasizes the value of a multidisciplinary approach, especially in places where hydatid disease is endemic.

This study highlights that hydatid cysts can occur in atypical locations such as the kidney, thyroid, spine, and subcutaneous tissue, in addition to the liver and lungs. These rare localizations can pose diagnostic challenges and may be misinterpreted as benign or malignant conditions. The variable clinical presentation of hydatid disease necessitates a comprehensive diagnostic approach combining clinical history, serological testing, and advanced imaging. Early diagnosis is crucial for preventing complications. Treatment should be tailored based on cyst size, location, and the patient's overall condition. Medical therapy, percutaneous interventions, or surgical procedures should be selected individually, with special caution in managing atypical localizations. A multidisciplinary approach enhances diagnostic accuracy and optimizes patient management, emphasizing the clinical significance of hydatid disease. Recognizing atypical cyst locations is essential for determining appropriate treatment strategies and ensuring long term follow up.

| 1. | Aydin S, Tek C, Dilek Gokharman F, Fatihoglu E, Nercis Kosar P. Isolated hydatid cyst of thyroid: An unusual case. Ultrasound. 2018;26:251-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Eren S, Aydın S, Kantarci M, Kızılgöz V, Levent A, Şenbil DC, Akhan O. Percutaneous management in hepatic alveolar echinococcosis: A sum of single center experiences and a brief overview of the literature. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2023;15:398-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Abdelhakim K, Khalil A, Haroune B, Oubaid M, Mondher M. A case of sacral hydatid cyst. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2014;5:434-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sarkar S, Wagh P, Jadhav U, Ghewade B. A Clinical Encounter With Intrathoracic Extrapulmonary Hydatid Disease. Cureus. 2023;15:e48496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ben Khalifa M, Ghannouchi M, Hammouda S, Taboubi W, Omri A, Nacef K, Boudokhane M. Primary subcutaneous hydatid cyst: An exceptional location. IDCases. 2022;30:e01627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mirzaei T, Hooshyar H. Primary subcutaneous hydatid cyst in scapula. Iran J Pathol. 2012;7:259-261. |

| 7. | Segura-Trepichio M, Montoza-Nuñez JM, Candela-Zaplana D, Herrero-Santacruz J, Pla-Mingorance F. Primary Sacral Hydatid Cyst Mimicking a Neurogenic Tumor in Chronic Low Back Pain: Case Report and Review of the Literature. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2016;7:S112-S116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sachar S, Goyal S, Goyal S, Sangwan S. Uncommon locations and presentations of hydatid cyst. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2014;4:447-452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kantarcı M, Aydın S, Oğul H, Kızılgöz V. New imaging techniques and trends in radiology. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2025;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kantarcı M, Aydın S, Kahraman A, Oğul H, İrgül B, Levent A. Virtual non-enhanced dual-energy computed tomography reconstruction: a candidate to replace true non-enhanced computed tomography scans in the setting of suspected liver alveolar echinococcosis. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2023;29:736-740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kantarci M, Aydin S, Eren S, Ogul H, Akhan O. Imaging Aspects of Hepatic Alveolar Echinococcosis: Retrospective Findings of a Surgical Center in Turkey. Pathogens. 2022;11:276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Turgut AT, Altin L, Topçu S, Kiliçoğlu B, Aliinok T, Kaptanoğlu E, Karademir A, Koşar U. Unusual imaging characteristics of complicated hydatid disease. Eur J Radiol. 2007;63:84-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pedrosa I, Saíz A, Arrazola J, Ferreirós J, Pedrosa CS. Hydatid disease: radiologic and pathologic features and complications. Radiographics. 2000;20:795-817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 498] [Cited by in RCA: 491] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Beggs I. The radiology of hydatid disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1985;145:639-648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 248] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Dziri C, Haouet K, Fingerhut A. Treatment of hydatid cyst of the liver: where is the evidence? World J Surg. 2004;28:731-736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gomez I Gavara C, López-Andújar R, Belda Ibáñez T, Ramia Ángel JM, Moya Herraiz Á, Orbis Castellanos F, Pareja Ibars E, San Juan Rodríguez F. Review of the treatment of liver hydatid cysts. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:124-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |