Published online Jun 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i6.106451

Revised: April 4, 2025

Accepted: April 24, 2025

Published online: June 19, 2025

Processing time: 92 Days and 4.1 Hours

Depression and anxiety are prevalent among university students worldwide, often coexisting with functional constipation (FC). Family relationships have been identified as crucial factors affecting mental health, yet the gender-specific associations between these conditions remain underexplored.

To assess prevalence of depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and FC among Chinese university students and explore their associations.

Using a cross-sectional survey design, data were collected from 12721 students at two universities in Jiangsu Province and Shandong Province. Depressive symp

The prevalence of self-reported depressive, anxiety, and comorbid depressive and anxiety symptoms was 16.3%, 24.9%, and 13.3%, respectively, whereas that of FC was 22%. Students with depressive symptoms were 1.811 times more likely to have FC than those without. Female gender, parental relationships, and lower household income were significant risk factors for both mental health conditions. For depressive symptoms, females experienced stronger effects from both parental conflict [odds ratio (OR) = 8.006 vs OR = 7.661 in males] and FC (OR = 1.954 vs OR = 1.628 in males). For anxiety symptoms, conflicted parental relationships had stronger effects in males (OR = 5.946) than females (OR = 4.262). Overall, poor parental relationships contributed to 38.6% of depressive and 33.5% of anxiety symptoms.

Family relationships significantly impact student mental health, with gender-specific patterns. Targeted interven

Core Tip: This study reveals gender-specific associations between mental health and functional constipation (FC) among Chinese university students. In a large-scale survey of 12721 students, females showed greater vulnerability to parental conflict for depressive symptoms and stronger associations between FC and depression, while males demonstrated higher susceptibility to parental conflict for anxiety symptoms. The study quantifies, for the first time, the substantial population impact of poor family relationships, contributing to 38.6% of depressive and 33.5% of anxiety, providing evidence for gender-differentiated family-based intervention strategies.

- Citation: Jiang BC, Zhang J, Yang M, Yang HD, Zhang XB. Prevalence and risk factors of depressive and anxiety symptoms and functional constipation among university students in Eastern China. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(6): 106451

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i6/106451.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i6.106451

Symptoms of depression and anxiety, two common mental health conditions, constitute a major health challenge that causes suffering to patients and also results in significant economic and social burdens. It has become a serious public health concern worldwide[1-4]. The World Health Organization initially estimated that there are 246 million people living with depressive disorders and 374 million people living with anxiety disorders, accounting for 28.9% and 31.0%, respectively, of all mental disorders[5]. Tian et al[6] reported that depressive and anxiety disorders constitute significant health challenges in China, with distinctive regional patterns and trends across different provinces, highlighting the need for targeted interventions tailored to local contexts. Although depression and anxiety have their own core symptoms, they are still considered heterogeneous disorders, some of which can be accompanied by suicidal thoughts or behaviors, with dire long-term adverse outcomes[7,8].

University students are in the transition period of adult life, facing multiple stressors such as increased academic pressure and anxiety about future career planning and the complexity of interpersonal relationships; therefore, many of them are in a state of vulnerable mental health[9-11]. Among university students, the prevalence of depressive symptoms is of particular concern[12]. Previous studies have shown a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms among undergraduates than in the general population, ranging from 2.1% to 88.8%, with a median prevalence of 34.8% and an increasing trend[13,14]. Depressive symptoms have a serious impact on academic performance, social functioning, and quality of life[15,16]. Moreover, depressive symptoms are not only related to current psychological states, but may also trigger a series of long-term negative consequences, such as suicidal tendencies and various chronic health problems[17-19].

The prevalence of anxiety symptoms among university students has also shown an increasing trend. Previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses spanning 17 years and 40 years, respectively, have shown that the prevalence of anxiety symptoms among undergraduate students worldwide ranges from 34.8% to 39.65%, with 19.1% and 10.3% having mild anxiety and severe anxiety, respectively[20,21]. Anxiety symptoms may diminish a student’s attention, memory, and learning effectiveness; affect self-esteem and socialization, contribute to psychological stress and isolation, and may promote additional health problems as a result of chronic psychological stress[22-25].

Numerous studies have reported that depressive and anxiety symptoms among university students are associated with different factors. For example, age less than 21 years, female gender, online behavioral problems, smoking, insomnia, low self-esteem, unhealthy diet, low level of physical activity, lack of social support, and low monthly income were associated with depressive symptoms; whereas malnutrition, excessive alcohol consumption, refugee status, overcrowding in the home, and specific age (18-20 years) were significantly associated with anxiety symptoms[22,26,27]. Among medical college students, there is a high prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms, with occupational depletion, dysfunctional coping strategies, low resilience, academic stress, financial difficulties, loneliness, low levels of social support, problems with Internet or smartphone use, and younger age being common risk factors[11,28]. Furthermore, a previous study showed that depressive and anxiety symptoms had a mediating role in the relationship between constipation and sleep quality, suggesting a possible association between depressive and anxiety symptoms and functional constipation (FC)[29].

Interestingly, depressive and anxiety symptoms are usually comorbid, which adds to the complexity of assessing the factors that influence the two disorders[30]. Considering the many different influencing factors, the prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms among university students is inconsistent. Therefore, identifying and understanding the prevalence and risk factors for depressive and anxiety symptoms are critical for strategy makers and psychological health practitioners to construct effective mental health prevention and intervention strategies.

Research on the association between FC and mental health status among university students has, to date, lacked a large-sample study. In the current study, we hypothesized that the prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms was high among university students, and that various demographic and sociological factors such as gender, age, parental relationship, and FC may be associated with the symptoms. The aims of the present study were to investigate the prevalence, risk factors, and their correlations with depressive and anxiety symptoms among university students in China; and to determine the relationship between depressive and anxiety symptoms and demographic characteristics. Through the present study, we hope to identify risk factors for depressive and anxiety symptoms, so as to provide appropriate management strategies with practical preventive and intervention measures to improve depressive and anxiety symptoms among university students.

An observational study was conducted between September and November 2023 at two universities in Jiangsu Province and Shandong Province, China. This study employed a multistage stratified sampling approach for school selection. Based on the Ministry of Education’s higher education classification, we selected provincial key comprehensive universities to minimize the impact of disciplinary differences on the outcome. To mitigate the effects of school characteristics and city differences, we collected data on socioeconomic factors such as family economic background and incorporated these as control variables in multivariate logistic regression analysis. Although our sample was drawn from two universities, it covered students from 13 provincial-level regions across China, which enhanced the representativeness of our sample.

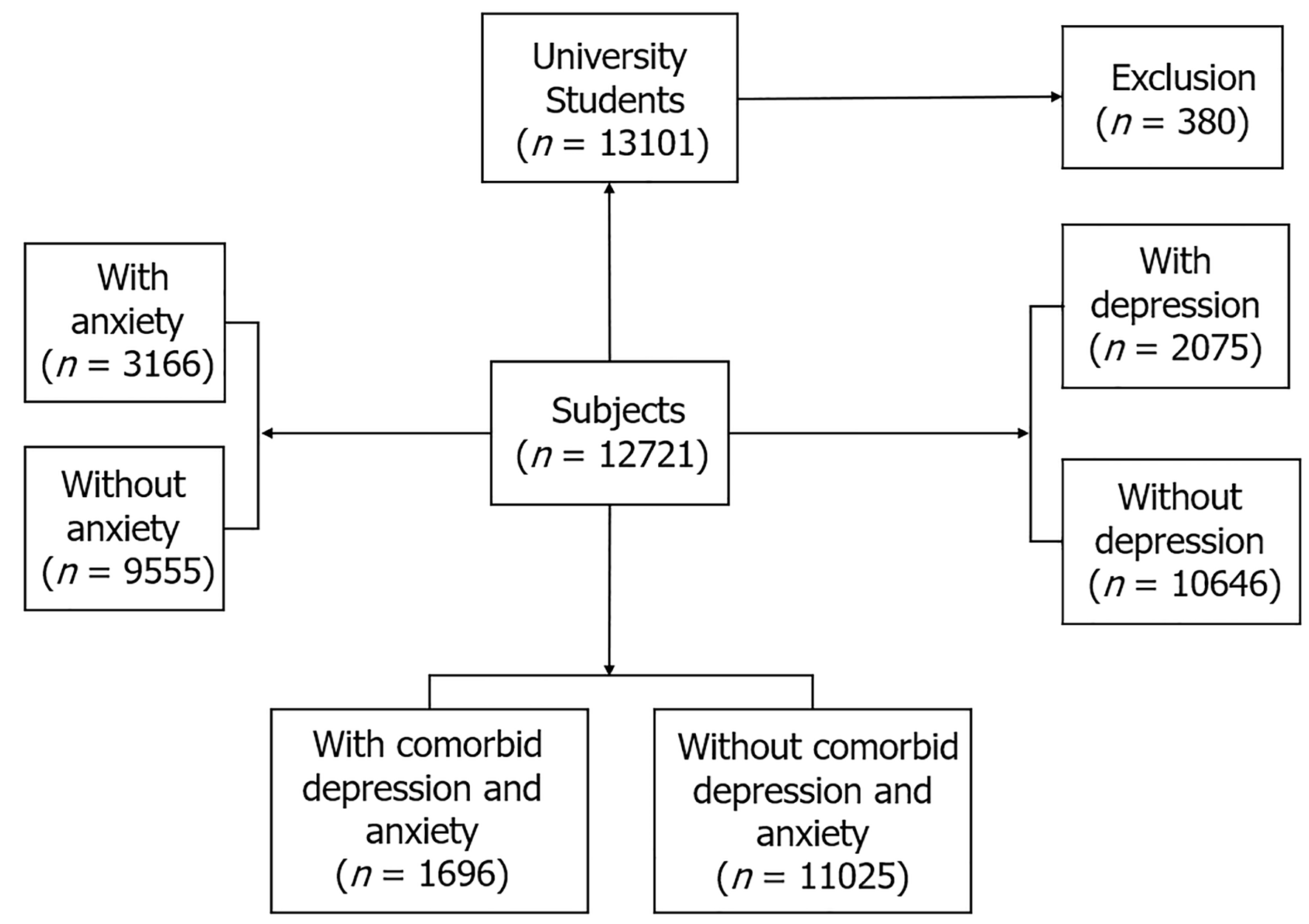

An anonymous online survey using the Wenjuanxing administration platform (https: //www.wjx.cn/app/survey.aspx) and WeChat were used to collect the data. The survey was administered to current university students, from first-year undergraduate to graduate students. Enrollment was conducted with an electronic note describing the purpose of the survey, procedures, and confidentiality of data, and consent was given by signing an electronic informed statement of approval. The participant recruitment process flowchart is shown in Figure 1. The survey was voluntary and respondents could withdraw at any time if they did not wish to complete it. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The Fourth People’s Hospital of Lianyungang, and confidentiality of the collected data was ensured.

A homemade socio-demographic questionnaire was designed to collect information including age (17–25 years old), gender, height, weight, smoking status (yes/no), parental relationship (harmony/moderate/conflict), annual household income (fair/good/better), and FC information (ROME IV) (yes/no). Considering the comprehension level of university students regarding family dynamics, parental relationship quality was assessed using a single question: What do you think is the relationship between your father and mother? Respondents selected from three options: (1) Harmonious (parents maintain a positive relationship with minimal conflict); (2) Moderate (parents have a generally good relationship with occasional disagreements); and (3) Conflicted (parents experience relationship difficulties with regular conflicts). The annual household income corresponds to fair, good, and better household incomes of less than ¥100000, ¥100000-¥200000, and more than ¥200000 per year, respectively.

The ROME IV diagnostic criteria for FC consists of eight questions used to self-report the presence or absence of constipation in participants[31]. Duration of illness requires that the last 3 months meet the criteria for a FC diagnosis, that symptoms appeared at least 6 months ago, and that other conditions that may result in constipation were excluded. To exclude constipation due to other causes, our questionnaire included a medical history screening section covering gastrointestinal organic diseases, metabolic diseases, and medication use. Participants who met Rome IV criteria but reported such medical histories were not diagnosed with FC. To minimize subjective judgment errors, we used the validated Rome IV standardized questionnaire, which provides detailed symptom descriptions and frequency quantification standards, requiring at least two or more symptoms to be confirmed to diagnose FC.

Depressive symptoms among university students were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) self-reported scale, which evaluated how many days in the past 2 weeks students experienced depressive symptoms[32]. The PHQ-9 consists of nine items and is 4-point scale from 0–3, with 0 for “not at all”, 1 for “a few days“, 2 for “more than half of the days”, and 3 for “almost every day”. The total score ranges from 0–27, and the overall score indicates the severity of depressive symptoms, with 0–4 being minimal, 5–9 being mild, 10–14 being moderate, 15–19 being moderate to severe, and 20–27 being severe[32]. The PHQ-9 has been applied to the Chinese population with good reliability and validity, and a cut-off score of 10 or more indicates the presence of depressive symptoms[33].

Anxiety symptoms were measured using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) self-report scale, which was utilized to assess the severity of anxiety symptoms over the past 2 weeks[34]. The GAD-7 is a four-point scale ranging from 0–3, with 0 being “not at all”, 1 being “several days”, 2 being “more than half the days”, and 3 being “nearly every day“. The total score ranges from 0 to 21, with 5–9 being mild, 10–14 being moderate, and 15-21 being severe. The GAD-7 has good reliability and validity in the Chinese population, and a cutoff score of 7 or more is considered as having anxiety symptoms[35,36]. Based on the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 cutoff scores, we identified those with total PHQ-9 score 10 and total GAD-7 score 7 as those with comorbid depressive and anxiety symptoms.

All statistical analyses were conducted utilizing Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software version 21.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, United States). Continuous variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation, and comparisons were made using the independent samples t-test or Student’s t-test. Categorical variables were represented in terms of percentages, and their intergroup differences were assessed employing the χ2 test. Logistic regression analysis was employed to identify the predictors influencing the presence of dichotomous dependent variables, such as the occurrence of depressive and anxiety symptoms. Gender-stratified analyses were conducted to explore potentially differentiated patterns of risk factors between male and female students, with interaction terms tested to assess the statistical significance of gender differences. Population attributable risk proportions (PARPs) were calculated to quantify the relative contribution of each identified risk factor to the overall depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and prevalence FC. PARPs were calculated using the formula PARP = [P × odds ratio (OR) - 1)]/[1 + P × (OR - 1)], where P and OR represent the prevalence of exposure to the risk factor in the study population and the adjusted OR obtained from the logistic regression models, respectively. The statistical significance for all tests was set at a P value of less than 0.05 (two-sided).

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Overall, we received 13101 questionnaires, of which 380 were excluded due to lack of valid information such as gender, age, and other questionnaire contents. Finally, 12721 responses were used in the study. Although the survey was conducted in two universities, university students came from 13 provinces in China: (1) Shandong Province; (2) Jiangsu Province; (3) Henan Province; (4) Hebei Province; (5) Shanxi Province; (6) Liaoning Province; (7) Fujian Province; (8) Jilin Province; (9) Hubei Province; (10) Tianjin Province; (11) Anhui Province; (12) Chongqing; and (13) Shanghai.

Participants were 48.7% (n = 6197) male and 51.3% (n = 6524) female, aged 17 years to 25 years, with a mean age of 19.63 years ± 1.20 years, mean height of 1.67 ± 0.08 m, mean weight of 61.89 kg ± 10.61 kg, and mean body mass index (BMI) of 22.04 kg/m2 ± 3.16 kg/m2. Among university students, 11.9% (n = 1518) were smokers and 22.0% (n = 2799) suffered from FC. The percentages of harmony, moderate, and conflict in parental relationship were 72.1% (n = 9166), 24.5% (n = 3111), and 3.5% (n = 444), respectively. The percentages of better, good, and fair annual household incomes were 41.6% (n = 5286), 40.5% (n = 5147), and 18.0% (n = 2288), respectively.

Table 1 compares the sociodemographic characteristics of the students. The prevalence of self-reported symptoms of depression (18.3% vs 14.2%, item 2 = 40.669, P < 0.001) and anxiety (28.4% vs 21.2%, item 2 = 89.278, P < 0.001) was significantly higher in females than in males. Smoking, parental relationship, annual household income, and FC showed significant differences between with and without depressive symptoms, and with and without anxiety symptoms (all P < 0.05). Height, weight, and BMI were not significantly different among students (all P > 0.05). The prevalence of depressive symptoms was higher among those 20–25 years of age than among those 17–19 years of age (17.0% vs 15.3%, item 2 = 6.579, P = 0.010); however, there was no significant difference between with and without anxiety symptoms (P = 0.191).

| Depression symptoms | Anxiety symptoms | |||||

| With (n = 2075) | Without (n = 10646) | P value | With (n = 3166) | Without (n = 9555) | P value | |

| Sex | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Male | 878 (14.2) | 5319 (85.8) | 1312 (21.2) | 4885 (78.8) | ||

| Female | 1197 (18.3) | 5327 (81.7) | 1854 (28.4) | 4670 (71.6) | ||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 19.68 (1.16) | 19.62 (1.20) | 0.033 | 19.62 (1.22) | 19.63 (1.19) | 0.802 |

| Age group | 0.010 | 0.191 | ||||

| 17-19 | 785 (15.3) | 4349 (84.7) | 1309 (25.5) | 3825 (74.5) | ||

| 20-25 | 1290 (17.0) | 6297 (83.0) | 1857 (24.5) | 5730 (75.5) | ||

| Height (m), mean (SD) | 1.67 (0.08) | 1.67 (0.08) | 0.682 | 1.67 (0.08) | 1.67 (0.08) | 0.771 |

| Weight (kg), mean (SD) | 62.02 (10.85) | 61.87 (10.56) | 0.553 | 61.94 (10.68) | 61.88 (10.58) | 0.783 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 22.08 (3.34) | 22.03 (3.13) | 0.563 | 22.05 (3.19) | 22.04 (3.16) | 0.933 |

| Smoking | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 412 (27.1) | 1106 (72.9) | 592 (39.0) | 926 (61.0) | ||

| No | 1663 (14.8) | 9540 (85.2) | 2574 (23.0) | 8629 (77.0) | ||

| Parental relationship | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Harmony | 942 (10.3) | 8224 (89.7) | 1668 (18.2) | 7498 (81.8) | ||

| Moderate | 909 (29.2) | 2202 (70.8) | 1255 (40.3) | 1856 (59.7) | ||

| Conflict | 224 (50.5) | 220 (49.5) | 243 (54.7) | 201 (45.3) | ||

| Annual household income | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Better | 602 (11.4) | 4684 (88.6) | 988 (18.7) | 4298 (81.3) | ||

| Good | 875 (17.0) | 4272 (83.0) | 1367 (26.6) | 3780 (73.4) | ||

| Fair | 598 (26.1) | 1690 (73.9) | 811 (35.4) | 1477 (64.6) | ||

| Functional constipation | < 0.001 | 0.002 | ||||

| Yes | 596 (21.3) | 2203 (78.7) | 634 (22.7) | 2165 (77.3) | ||

| No | 1479 (14.9) | 8443 (85.1) | 2532 (25.5) | 7390 (74.5) | ||

The median (interquartile range) PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores among students were 4.0 (1.0, 8.0) and 2.0 (0, 6.0), respectively. Our results revealed that the overall prevalence of self-reported depressive, anxiety, and comorbid depressive and anxiety symptoms were 16.3%, 24.9%, and 13.3%, respectively. The proportions of students with self-reported depressive symptoms that were mild, moderate, moderately severe, and severe were 28.8%, 10.1%, 4.1%, and 2.1%, respectively. Meanwhile, the proportions of students with self-reported anxiety symptoms that were mild, moderate, and severe were 24.1%, 7.1%, and 4.0%, respectively (Table 2).

| Depressive symptoms | Anxiety symptoms | Comorbid depression and anxiety symptoms | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Minimal | 6986 | 54.9 | 8245 | 64.8 | 11025 | 86.7% |

| Mild | 3660 | 28.8 | 3070 | 24.1 | - | - |

| Moderate | 1280 | 10.1 | 901 | 7.1 | - | - |

| Moderately severe | 524 | 4.1 | - | - | - | - |

| Severe | 271 | 2.1 | 505 | 4.0 | - | - |

| Overall prevalence | 2075 | 16.3 | 3166 | 24.9 | 1696 | 13.3 |

Univariate analyses revealed that height, weight, and BMI were not significantly different in the self-reported prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms (all P > 0.05). In addition, age was not a significant factor in the self-reported prevalence of anxiety symptoms (P > 0.05); therefore, the mentioned factors were not included in logistic regression analyses.

As shown in Table 3, binary logistic regression revealed that depressive symptoms were positively associated with female gender (B = 0.290, P < 0.001, OR = 1.336, 95%CI: 1.209–1.477) and FC (B = 0.594, P < 0.001, OR = 1.811, 95%CI: 1.617–2.029). Meanwhile, moderate (B = 1.206, P < 0.001, OR = 3.340, 95%CI: 2.934–3.802) and conflicted (B = 2.055, P < 0.001, OR = 7.807, 95%CI: 6.373–9.564) parental relationships were positively associated with depressive symptoms compared with harmonious parental relationships. Good (B = 0.254, P < 0.001, OR = 1.289, 95%CI: 1.129–1.472) and fair (B = 0.701, P < 0.001, OR = 2.016, 95%CI: 1.762–2.307) annual household incomes were positively associated with depressive symptoms compared with better annual household income. There was no significant correlation between age (P = 0.220) and smoking (P = 0.469) and depressive symptoms.

| Depressive symptoms | Anxiety symptoms | |||||

| OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Female | 1.336 | 1.209-1.477 | < 0.001 | 1.445 | 1.328-1.572 | < 0.001 |

| Age group (years) | - | - | - | |||

| 17-19 | 1 | - | - | - | ||

| 20-25 | 1.066 | 0.963-1.180 | 0.220 | - | - | - |

| Smoking | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 0.935 | 0.779-1.122 | 0.469 | 0.919 | 0.783-1.079 | 0.303 |

| Parental relationship | ||||||

| Harmony | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Moderate | 3.340 | 2.934-3.802 | < 0.001 | 2.651 | 2.367-2.969 | < 0.001 |

| Conflict | 7.807 | 6.373-9.564 | < 0.001 | 4.937 | 4.052-6.014 | < 0.001 |

| Annual household income | ||||||

| Better | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Good | 1.289 | 1.129-1.472 | < 0.001 | 1.297 | 1.166-1.443 | < 0.001 |

| Fair | 2.016 | 1.762-2.307 | < 0.001 | 1.820 | 1.621-2.044 | |

| Functional constipation | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 1.811 | 1.617-2.029 | < 0.001 | 0.931 | 0.839-1.033 | 0.180 |

Regarding anxiety symptoms, binary logistic regression indicated that female sex (B = 0.368, P < 0.001, OR = 1.445, 95%CI: 1.328–1.572); moderate (B = 0.975, P < 0.001, OR = 2.651, 95%CI: 2.367–2.969) and conflicted (B = 1.597, P < 0.001, OR = 4.937, 95%CI: 4.052–6.014) parental relationships; and good (B = 0.260, P < 0.001, OR = 1.297, 95%CI: 1.166–1.443) and fair (B = 0.599, P < 0.001, OR = 1.820, 95%CI: 1.621–2.044) annual household income were positively correlated with anxiety symptoms. Smoking (P = 0.303) and FC (P = 0.180) were not risk factors for anxiety symptoms.

Gender-stratified analyses revealed distinct patterns of risk factors for both depressive and anxiety symptoms between male and female students (Table 4). For depressive symptoms, significant interactions between gender and risk factors were observed for age group (P < 0.001), smoking (P = 0.016), parental relationship (P < 0.001), annual household income (P < 0.001), and FC (P < 0.001).

| Risk factor | Depressive symptoms | Anxiety symptoms | ||||||||

| Male (n = 6197) | Female (n = 6524) | P value for interaction1 (n = 12721) | Male (n = 6197) | Female (n = 6524) | P value for interaction1 (n = 12721) | |||||

| OR | 95%CI | OR | 95%CI | OR | 95%CI | OR | 95%CI | |||

| Age group (years) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| 17–19 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 20–25 | 1.048 | 0.898–1.223 | 1.079 | 0.942–1.236 | 0.865 | 0.760–0.985 | 0.915 | 0.817–1.025 | ||

| Smoking | 0.016 | 0.056 | ||||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Yes | 1.369 | 1.060–1.769 | 0.839 | 0.649–1.085 | 1.245 | 0.994–1.558 | 0.944 | 0.752–1.185 | ||

| Parental relationship | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Harmony | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Moderate | 2.817 | 2.321–3.418 | 3.886 | 3.262–4.628 | 2.561 | 2.167–3.027 | 2.790 | 2.389–3.258 | ||

| Conflict | 7.661 | 5.694–10.309 | 8.009 | 6.059–10.586 | 5.946 | 4.466–7.917 | 4.262 | 3.250–5.589 | ||

| Annual household income | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Better | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Good | 1.483 | 1.214–1.811 | 1.183 | 0.990–1.415 | 1.317 | 1.122–1.546 | 1.285 | 1.113–1.483 | ||

| Fair | 2.712 | 2.207–3.332 | 1.619 | 1.352–1.938 | 2.048 | 1.715–2.445 | 1.678 | 1.439–1.958 | ||

| Functional constipation | < 0.001 | 0.061 | ||||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Yes | 1.628 | 1.372–1.930 | 1.954 | 1.676–2.278 | 0.861 | 0.736–1.007 | 0.985 | 0.857–1.133 | ||

In male students, smoking was associated with increased odds of depressive symptoms (OR = 1.369, 95%CI: 1.060–1.769), while this association was not significant in females (OR = 0.839, 95%CI: 0.649–1.085). Both moderate (OR = 2.817, 95%CI: 2.321–3.418) and conflicted (OR = 7.661, 95%CI: 5.694–10.309) parental relationships significantly increased the risk of depressive symptoms in males compared to harmonious relationships. Similarly, in females, moderate (OR = 3.886, 95%CI: 3.262–4.628) and conflicted (OR = 8.009, 95%CI: 6.059–10.586) parental relationships were strongly associated with depressive symptoms, with the effect being more pronounced than in males. Regarding socioeconomic factors, both good (OR = 1.483, 95%CI: 1.214–1.811) and fair (OR = 2.712, 95%CI: 2.207–3.332) annual household income significantly increased the risk of depressive symptoms in males compared to better income. In females, fair annual household income showed a similar but less pronounced effect (OR = 1.619, 95%CI: 1.352–1.938), whereas good income was not significantly associated with depressive symptoms (OR = 1.183, 95%CI: 0.990–1.415). FC was associated with increased odds of depressive symptoms in both genders, with a stronger effect observed in females (OR = 1.954, 95%CI: 1.676–2.278) than in males (OR = 1.628, 95%CI: 1.372–1.930), and the gender interaction was statistically significant (P < 0.001).

For anxiety symptoms, significant gender interactions were observed for age group (P < 0.001), parental relationship

In male students, being in the 20–25 age group was associated with decreased odds of anxiety symptoms compared to the 17–19 age group (OR = 0.865, 95%CI: 0.760–0.985), whereas no significant association was found in females (OR = 0.915, 95%CI: 0.817–1.025). Both moderate (OR = 2.561, 95%CI: 2.167–3.027) and conflicted (OR = 5.946, 95%CI: 4.466–7.917) parental relationships significantly increased the risk of anxiety symptoms in males. Similarly, in females, moderate (OR = 2.790, 95%CI: 2.389–3.258) and conflicted (OR = 4.262, 95%CI: 3.250–5.589) parental relationships were strongly associated with anxiety symptoms, though the effect of conflict was less pronounced than in males. Regarding annual household income, both good (OR = 1.317, 95%CI: 1.122–1.546) and fair (OR = 2.048, 95%CI: 1.715–2.445) income levels significantly increased the risk of anxiety symptoms in males compared to better income. Similar associations were observed in females for both good (OR = 1.285, 95%CI: 1.113–1.483) and fair (OR = 1.678, 95%CI: 1.439–1.958) income levels, although the magnitude of the effect was smaller for fair income compared to males. Unlike with depressive symptoms, FC was not significantly associated with anxiety symptoms in either males (OR = 0.861, 95%CI: 0.736–1.007) or females (OR = 0.985, 95%CI: 0.857–1.133).

To quantify the population-level impact of the identified risk factors, we calculated PARPs, which estimate the proportion that could potentially be prevented if a particular risk factor were eliminated from the population.

Table 5 presents the PARPs for depressive symptoms by gender. Overall, parental relationship quality emerged as the most significant contributor to depressive symptoms, with moderate and conflicted relationships jointly accounting for 38.6% (95%CI: 35.1–42.0) of depressive symptom in the total population. The PARP was slightly higher in females (40.3%, 95%CI: 36.7–43.8) than in males (36.1%, 95%CI: 32.2–39.9), consistent with the stronger OR observed in the female subgroup. Annual household income was the second largest contributor, with fair household income associated with a PARP of 22.7% (95%CI: 19.1–26.2) overall. Gender differences were notable, with a substantially higher number of PARPs in males (27.3%, 95%CI: 22.9–31.6) compared to females (18.2%, 95%CI: 14.4–21.9), reflecting the stronger association between income status and depressive symptoms in male students. FC demonstrated a significant contribution to the population of depressive symptoms, with an overall PARP of 15.1% (95%CI: 11.9–18.2). Consistent with the gender-stratified analysis showing a stronger association in females, the PARP for FC was higher in females (17.4%, 95%CI: 13.0–21.7) than in males (12.1%, 95%CI: 8.2–16.0). Smoking contributed modestly to the overall outcome with a PARP of 1.2% (95%CI: 0.0–3.0), but showed significant gender variation with a notable PARP in males (4.1%, 95%CI: 0.7–7.4) and no significant contribution in females.

| Risk factor | Overall PARP (95%CI) | Male PARP (95%CI) | Female PARP (95%CI) | P for interaction1 |

| Depressive symptoms | ||||

| Parental relationship | < 0.001 | |||

| Moderate vs harmonious | 22.3 (19.7–4.8) | 20.5 (17.6–23.4) | 23.9 (21.1–26.6) | |

| Conflicted vs harmonious | 16.3 (14.1–8.4) | 15.6 (13.2–18.1) | 16.4 (13.9–18.9) | |

| Annual household income | < 0.001 | |||

| Good vs better | 7.8 (5.3–10.2) | 10.6 (7.2–13.9) | 5.0 (2.4–7.6) | |

| Fair vs better | 22.7 (19.1–6.2) | 27.3 (22.9–31.6) | 18.2 (14.4–21.9) | |

| FC (yes vs no) | 15.1 (11.9–8.2) | 12.1 (8.2–16.0) | 17.4 (13.0–21.7) | < 0.001 |

| Smoking (yes vs no) | 1.2 (0.0–3.0) | 4.1 (0.7–7.4) | −1.8 (−4.1 to 0.5) | 0.016 |

| Anxiety symptoms | ||||

| Parental relationship | < 0.001 | |||

| Moderate vs harmonious | 19.7 (17.4–2.0) | 19.9 (17.2–22.6) | 19.6 (17.0–22.1) | |

| Conflicted vs harmonious | 13.8 (11.8–5.7) | 15.2 (12.8–17.5) | 12.4 (10.2–14.6) | |

| Annual household income | < 0.001 | |||

| Good vs better | 9.3 (6.2–12.4) | 9.5 (5.8–13.1) | 9.2 (5.2–13.1) | |

| Fair vs better | 18.4 (15.2–1.5) | 21.6 (17.5–25.6) | 15.9 (12.3–19.4) | |

| FC (yes vs no) | –1.5 (–4.1 to 1.0) | –2.7 (–5.9 to 0.4) | –0.3 (–3.6 to 2.9) | 0.061 |

| Smoking (yes vs no) | 0.8 (–0.5–2.1) | 3.5 (0.1–6.8) | –0.9 (–3.4 to 1.5) | 0.056 |

| FC | ||||

| Depressive symptoms (yes vs no) | 11.7 (9.2–14.1) | 9.7 (6.5–12.8) | 13.2 (10.0–16.3) | < 0.001 |

| Anxiety symptoms (yes vs no) | −1.7 (–4.3 to 0.9) | –3.1 (–6.3 to 0.1) | –0.5 (–3.8 to 2.9) | 0.061 |

For anxiety symptoms, parental relationship quality remained the predominant contributor, with moderate and conflicted relationships accounting for 33.5% (95%CI: 30.3–36.6) of overall anxiety symptoms. Unlike with depressive symptoms, the PARP for parental relationship was higher in males (35.1%, 95%CI: 31.4–38.7) than in females (32.0%, 95%CI: 28.4–35.5), despite similar ORs. Socioeconomic factors also contributed substantially to anxiety symptoms, with fair household income associated with a PARP of 18.4% (95%CI: 15.2–21.5) overall. As with depressive symptoms, this PARP was markedly higher in males (21.6%, 95%CI: 17.5–25.6) than in females (15.9%, 95%CI: 12.3–19.4). Good income contributed an additional 9.3% (95%CI: 6.2–12.4) to the population, with similar PARPs in males (9.5%, 95%CI: 5.8–13.1) and females (9.2%, 95%CI: 5.2–13.1). Notably, FC did not significantly contribute to anxiety symptoms at the population level (PARP = −1.5%, 95%CI: −4.1 to 1.0), confirming the differential impact of FC on depressive vs anxiety symptoms observed in our regression analyses.

We further analyzed the potential contribution of psychological factors to FC. Depressive symptoms accounted for 11.7% (95%CI: 9.2–14.1) of FC in the total population, with a higher PARP in females (13.2%, 95%CI: 10.0–16.3) than in males (9.7%, 95%CI: 6.5–12.8). In contrast, anxiety symptoms did not significantly contribute to FC (PARP = −1.7%, 95%CI: −4.3 to 0.9).

Our study revealed the following major findings: (1) The prevalence of self-reported depressive, anxiety, and comorbid depressive and anxiety symptoms among university students was 16.3%, 24.9%, and 13.3%, respectively; (2) Female gender, parental relationships, and annual household income were risk factors for depressive and anxiety symptoms among university students, with gender-stratified analysis revealing that both parental conflict and FC had stronger effects on females compared to males; (3) The prevalence of FC among university students was 22%, and was 1.81 fold higher among students with depressive symptoms than students without depressive symptoms; and (4) PARP analysis identified poor parental relationships as the most significant modifiable risk factor, contributing to 38.6% of depressive and 33.5% of anxiety symptoms, with household income being the second largest contributor (22.7% for depressive and 18.4% for anxiety symptoms).

Regarding the first finding, although epidemiologic surveys of depressive and anxiety symptoms among university students have been conducted, the results have been inconsistent. For example, the meta-analysis by Jahrami et al[37] reported a global prevalence of 32.5% for both depression and anxiety among students, while Martínez-Líbano et al[38] reported percentages of 63.1% and 69.2% for depression and anxiety, respectively. Ramón-Arbués et al[26] reported results of 3.8% and 24.5% for depressive and anxiety symptoms, respectively, among students. Finally, two studies reported the prevalence of depressive symptoms among Chinese university students to be 28.4%, while that of anxiety ranged from 7.4% to 43%[39,40]. These discrepancies in results may be related to different ethnicities and cultural backgrounds of students, as well as the survey instruments and research methods used to collect and analyze the data. Notably, previous studies have reported the prevalence of depression and anxiety among college students during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic[41-44] and, although the results were varied, the overall findings indicated that the status of mental health among college students was of concern.

In the current study, the prevalence of comorbid depressive and anxiety symptoms among university students was 13.3%, a finding that highlights the overlapping nature of these two mental health conditions. Interestingly, a network approach study suggested that the most influential central symptom in the depression-anxiety comorbidity profile trended away from the sad mood of depression towards the excessive worry of anxiety[18]. Furthermore, the distribution of severity of depressive and anxiety symptoms revealed a stratification among university students, with our findings showing a decreasing trend in prevalence from mild to severe symptoms[45,46]. In contrast, an increasing trend was reported in the study of Rabby et al[47]. Inconsistent results may be related to the survey instrument utilized, culture, professional background, economic status, etc. Overall, the findings indicate that early identification of depressive and anxiety symptoms in the university setting is needed to implement early intervention strategies.

Another major finding of the current study was that female gender, poor parental relationships, and lower household income were risk factors for depressive and anxiety symptoms among university students. Previous studies have reported that variations in factors such as hormone levels, socio-cultural factors, and stress coping styles among females were significantly associated with symptoms of depression and anxiety[46,48-51]. Strained or conflicted relationships between parents may weaken an individual's social and emotional support system, thus increasing vulnerability to stress and serving as a risk factor for depression and anxiety[52,53]. This finding suggests that interventions targeting parental relationships might have greater population-level impact for anxiety prevention in female students. Likewise, family income may increase psychological stress, which is further compounded by academic and employment duties, contributing to the development of emotional problems and feelings of anxiety[54-56]. In addition, there are many more factors that may influence the psychological state of university students, such as age, inappropriate use of electronic devices, lower psychological resilience, and parental mental state[28,57-59]. Overall, the previous and current findings underscore the important roles of gender and family background in symptoms of depression and anxiety, and warrant further attention.

The final major finding of the present study was that the prevalence of FC among university students was 22%, and was 1.811 times higher among university students with depressive symptoms than those without. This finding indicates that FC and depressive symptoms may have a close association. Deng et al[60] conducted a two-sample Mendelian randomization study that demonstrated a causal relationship between major depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, and constipation, providing genetic evidence for the bidirectionality of these relationships. Gender difference in FC attribution highlights the potentially greater impact of gastrointestinal function on mental health among female students. The findings also support a bidirectional relationship between depressive symptoms and FC, with stronger influences observed in the female population. Genome-wide pleiotropic analysis demonstrated that pleiotropic genetic determinants of the association between gastrointestinal disorders and psychiatric disorders were widely distributed across the genome[61]. Furthermore, a study with over 1.25 million hospitalized patients showed that constipation increased the odds of depression and anxiety[62]. The classic mechanism hypothesis is that there is a vicious cycle between neuroinflammation, the microbiota-gut-brain axis, and symptoms of depression[63]. FC may also be a component of somatization symptoms of depression, which also explains the increased proportion of FC among students with depressive symptoms compared to those without, and warrants further investigation.

Our findings have clinical and policy implications. From a clinical perspective, the nearly two-fold increased risk of FC among students with depressive symptoms suggests that screening for FC in students with depressive symptoms could identify subsequent intervention, particularly given the substantial 22% FC prevalence. From a policy perspective, higher education institutions should enhance attention to student mental health through integrated services, combining mental health resources with student health centers to provide comprehensive support. Second, a multi-tiered support system is needed. Specifically, students with mild symptoms may benefit more from low-intensity interventions such as mental health education and self-help strategies, while students with moderate to severe symptoms may need more specialized counseling or therapy. Finally, institutions of higher education should enhance students’ mental resilience and coping skills by providing mental health counseling, providing mental health courses and activities, and establishing emergency intervention mechanisms for responding to mental health crises.

Nevertheless, there were several limitations to this study. First, the dataset was based on an online survey and self-reported, and may have been subject to selection bias or recall bias. Second, the cross-sectional design of the study limited our ability to infer causal relationships. Third, despite our efforts to control for school characteristics and city differences, our study sampled from only two universities, which may not fully represent the diversity of Chinese higher education institutions. Fourth, this study did not investigate the potential impact of marriage or intimate relationships on students’ mental and physical health. Although most college students are not yet married, relationship status may influence psychological health and gastrointestinal function through the neuroendocrine and autonomic nervous systems. Fifth, this study did not assess the relationship between depressive and anxiety symptoms and other comorbid diseases or medication use. Finally, the present study failed to cover all possible risk factors, such as individuals’ coping strategies, quality of social support, and online social behaviors, all of which need to include in future research.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates the high prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms, as well as their severity distribution, among university students. Female gender, parental relationships, and household income were risk factors for depressive and anxiety symptoms among university students. Meanwhile, FC was a risk factor for depressive symptoms and there was evidence that the two conditions may interact. These findings should be used to improve the effectiveness of university mental health services and increase awareness of depression and anxiety and their influencing factors among university students, to further promote mental health[54].

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all study participants involved in data collection.

| 1. | GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396:1204-1222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11327] [Cited by in RCA: 9637] [Article Influence: 1927.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (35)] |

| 2. | GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9:137-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 436] [Cited by in RCA: 2713] [Article Influence: 904.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hannah K, Marie K, Olaf H, Stephan B, Andreas D, Wilson Michael L, Till B, Peter D. The global economic burden of health anxiety/hypochondriasis- a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2023;23:2237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Christensen MK, Lim CCW, Saha S, Plana-Ripoll O, Cannon D, Presley F, Weye N, Momen NC, Whiteford HA, Iburg KM, McGrath JJ. The cost of mental disorders: a systematic review. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2020;29:e161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | World Health Organization. World Mental Health Report: transforming mental health for all. 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/mental-health-and-substance-use/world-mental-health-report. |

| 6. | Tian W, Yan G, Xiong S, Zhang J, Peng J, Zhang X, Zhou Y, Liu T, Zhang Y, Ye P, Zhao W, Tian M. Burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in China and its provinces, 1990-2021: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Br J Psychiatry. 2025;1-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Herrman H, Patel V, Kieling C, Berk M, Buchweitz C, Cuijpers P, Furukawa TA, Kessler RC, Kohrt BA, Maj M, McGorry P, Reynolds CF 3rd, Weissman MM, Chibanda D, Dowrick C, Howard LM, Hoven CW, Knapp M, Mayberg HS, Penninx BWJH, Xiao S, Trivedi M, Uher R, Vijayakumar L, Wolpert M. Time for united action on depression: a Lancet-World Psychiatric Association Commission. Lancet. 2022;399:957-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 494] [Cited by in RCA: 519] [Article Influence: 173.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sander LB, Beisemann M, Doebler P, Micklitz HM, Kerkhof A, Cuijpers P, Batterham P, Calear A, Christensen H, De Jaegere E, Domhardt M, Erlangsen A, Eylem-van Bergeijk O, Hill R, Mühlmann C, Österle M, Pettit J, Portzky G, Steubl L, van Spijker B, Tighe J, Werner-Seidler A, Büscher R. The Effects of Internet-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Suicidal Ideation or Behaviors on Depression, Anxiety, and Hopelessness in Individuals With Suicidal Ideation: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Individual Participant Data. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e46771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Akram U, Irvine K, Gardani M, Allen S, Akram A, Stevenson JC. Prevalence of anxiety, depression, mania, insomnia, stress, suicidal ideation, psychotic experiences, & loneliness in UK university students. Sci Data. 2023;10:621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Freitas PHB, Meireles AL, Ribeiro IKDS, Abreu MNS, Paula W, Cardoso CS. Symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress in health students and impact on quality of life. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2023;31:e3884. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mhata NT, Ntlantsana V, Tomita AM, Mwambene K, Saloojee S. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and burnout in medical students at the University of Namibia. S Afr J Psychiatr. 2023;29:2044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Thapar A, Eyre O, Patel V, Brent D. Depression in young people. Lancet. 2022;400:617-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 371] [Article Influence: 123.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Agyapong-Opoku G, Agyapong B, Obuobi-Donkor G, Eboreime E. Depression and Anxiety among Undergraduate Health Science Students: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Behav Sci (Basel). 2023;13:1002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Husky MM, Léon C, du Roscoät E, Vasiliadis HM. Prevalence of past-year major depressive episode among young adults between 2005 and 2021: Results from four national representative surveys in France. J Affect Disord. 2023;342:192-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Beiter R, Nash R, McCrady M, Rhoades D, Linscomb M, Clarahan M, Sammut S. The prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and stress in a sample of college students. J Affect Disord. 2015;173:90-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 713] [Cited by in RCA: 729] [Article Influence: 72.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Maddalena NCP, Lucchetti ALG, Moutinho ILD, Ezequiel ODS, Lucchetti G. Mental health and quality of life across 6 years of medical training: A year-by-year analysis. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2024;70:298-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | N Fountoulakis K, N Karakatsoulis G, Abraham S, Adorjan K, Ahmed HU, Alarcón RD, Arai K, Auwal SS, Bobes J, Bobes-Bascaran T, Bourgin-Duchesnay J, Bredicean CA, Bukelskis L, Burkadze A, Cabrera Abud II, Castilla-Puentes R, Cetkovich M, Colon-Rivera H, Corral R, Cortez-Vergara C, Crepin P, de Berardis D, Zamora Delgado S, de Lucena D, de Sousa A, di Stefano R, Dodd S, Elek LP, Elissa A, Erdelyi-Hamza B, Erzin G, Etchevers MJ, Falkai P, Farcas A, Fedotov I, Filatova V, Fountoulakis NK, Frankova I, Franza F, Frias P, Galako T, Garay CJ, Garcia-Álvarez L, García-Portilla P, Gonda X, Gondek TM, Morera González D, Gould H, Grandinetti P, Grau A, Groudeva V, Hagin M, Harada T, Hasan TM, Azreen Hashim N, Hilbig J, Hossain S, Iakimova R, Ibrahim M, Iftene F, Ignatenko Y, Irarrazaval M, Ismail Z, Ismayilova J, Jacobs A, Jakovljević M, Jakšić N, Javed A, Yilmaz Kafali H, Karia S, Kazakova O, Khalifa D, Khaustova O, Koh S, Kopishinskaia S, Kosenko K, Koupidis SA, Kovacs I, Kulig B, Lalljee A, Liewig J, Majid A, Malashonkova E, Malik K, Iqbal Malik N, Mammadzada G, Mandalia B, Marazziti D, Marčinko D, Martinez S, Matiekus E, Mejia G, Memon RS, Meza Martínez XE, Mickevičiūtė D, Milev R, Mohammed M, Molina-López A, Morozov P, Muhammad NS, Mustač F, Naor MS, Nassieb A, Navickas A, Okasha T, Pandova M, Panfil AL, Panteleeva L, Papava I, Patsali ME, Pavlichenko A, Pejuskovic B, Pinto da Costa M, Popkov M, Popovic D, Raduan NJN, Vargas Ramírez F, Rancans E, Razali S, Rebok F, Rewekant A, Reyes Flores EN, Rivera-Encinas MT, Saiz PA, Sánchez de Carmona M, Saucedo Martínez D, Saw JA, Saygili G, Schneidereit P, Shah B, Shirasaka T, Silagadze K, Sitanggang S, Skugarevsky O, Spikina A, Mahalingappa SS, Stoyanova M, Szczegielniak A, Tamasan SC, Tavormina G, Tavormina MGM, Theodorakis PN, Tohen M, Tsapakis EM, Tukhvatullina D, Ullah I, Vaidya R, Vega-Dienstmaier JM, Vrublevska J, Vukovic O, Vysotska O, Widiasih N, Yashikhina A, Prezerakos PE, Berk M, Levaj S, Smirnova D. Results of the COVID-19 mental health international for the health professionals (COMET-HP) study: depression, suicidal tendencies and conspiracism. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2023;58:1387-1410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tao Y, Wang S, Tang Q, Ma Z, Zhang L, Liu X. Centrality depression-anxiety symptoms linked to suicidal ideation among depressed college students--A network approach. Psych J. 2023;12:735-745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Liao SJ, Fang YW, Liu TT. Exploration of related factors of suicide ideation in hospitalized older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2023;23:749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ahmed I, Hazell CM, Edwards B, Glazebrook C, Davies EB. A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies exploring prevalence of non-specific anxiety in undergraduate university students. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23:240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Chi T, Cheng L, Zhang Z. Global prevalence and trend of anxiety among graduate students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. 2023;13:e2909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ramón-Arbués E, Gea-Caballero V, Granada-López JM, Juárez-Vela R, Pellicer-García B, Antón-Solanas I. The Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety and Stress and Their Associated Factors in College Students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:7001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 48.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gao W, Ping S, Liu X. Gender differences in depression, anxiety, and stress among college students: A longitudinal study from China. J Affect Disord. 2020;263:292-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 478] [Cited by in RCA: 377] [Article Influence: 75.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 24. | Sonmez Y, Akdemir M, Meydanlioglu A, Aktekin MR. Psychological Distress, Depression, and Anxiety in Nursing Students: A Longitudinal Study. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;11:636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Cuder A, Živković M, Doz E, Pellizzoni S, Passolunghi MC. The relationship between math anxiety and math performance: The moderating role of visuospatial working memory. J Exp Child Psychol. 2023;233:105688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ramón-Arbués E, Sagarra-Romero L, Echániz-Serrano E, Granada-López JM, Cobos-Rincón A, Juárez-Vela R, Navas-Echazarreta N, Antón-Solanas I. Health-related behaviors and symptoms of anxiety and depression in Spanish nursing students: an observational study. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1265775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Essayagh F, Essayagh M, Essayagh S, Marc I, Bukassa G, El Otmani I, Kouyate MF, Essayagh T. The prevalence and risk factors for anxiety and depression symptoms among migrants in Morocco. Sci Rep. 2023;13:3740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ramadianto AS, Kusumadewi I, Agiananda F, Raharjanti NW. Symptoms of depression and anxiety in Indonesian medical students: association with coping strategy and resilience. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22:92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Papi S, Barmala A, Amiri Z, Vakili-Basir A, Cheraghi M, Nejadsadeghi E. Mediating Roles of Stress, Anxiety, and Depression in the Relationship between Constipation and Sleep Quality among the Elderly: Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). Sleep Sci. 2023;16:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Huang Y, Wang Y, Wang H, Liu Z, Yu X, Yan J, Yu Y, Kou C, Xu X, Lu J, Wang Z, He S, Xu Y, He Y, Li T, Guo W, Tian H, Xu G, Xu X, Ma Y, Wang L, Wang L, Yan Y, Wang B, Xiao S, Zhou L, Li L, Tan L, Zhang T, Ma C, Li Q, Ding H, Geng H, Jia F, Shi J, Wang S, Zhang N, Du X, Du X, Wu Y. Prevalence of mental disorders in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:211-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1590] [Cited by in RCA: 1358] [Article Influence: 226.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Mearin F, Lacy BE, Chang L, Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Simren M, Spiller R. Bowel Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1781] [Cited by in RCA: 1895] [Article Influence: 210.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 32. | Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21545] [Cited by in RCA: 28865] [Article Influence: 1202.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Zhou Y, Shi H, Liu Z, Peng S, Wang R, Qi L, Li Z, Yang J, Ren Y, Song X, Zeng L, Qian W, Zhang X. The prevalence of psychiatric symptoms of pregnant and non-pregnant women during the COVID-19 epidemic. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10:319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-1097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11947] [Cited by in RCA: 18821] [Article Influence: 990.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Lu W, Bian Q, Wang W, Wu X, Wang Z, Zhao M. Chinese version of the Perceived Stress Scale-10: A psychometric study in Chinese university students. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0189543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Tong X, An D, McGonigal A, Park SP, Zhou D. Validation of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) among Chinese people with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2016;120:31-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 332] [Article Influence: 33.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Jahrami H, AlKaabi J, Trabelsi K, Pandi-Perumal SR, Saif Z, Seeman MV, Vitiello MV. The worldwide prevalence of self-reported psychological and behavioral symptoms in medical students: An umbrella review and meta-analysis of meta-analyses. J Psychosom Res. 2023;173:111479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Martínez-Líbano J, Torres-Vallejos J, Oyanedel JC, González-Campusano N, Calderón-Herrera G, Yeomans-Cabrera MM. Prevalence and variables associated with depression, anxiety, and stress among Chilean higher education students, post-pandemic. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1139946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Gao L, Xie Y, Jia C, Wang W. Prevalence of depression among Chinese university students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2020;10:15897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Liu X, Ping S, Gao W. Changes in Undergraduate Students' Psychological Well-Being as They Experience University Life. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (19)] |

| 41. | Alshehri A, Alshehri B, Alghadir O, Basamh A, Alzeer M, Alshehri M, Nasr S. The prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms among first-year and fifth-year medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23:411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Witteveen AB, Young SY, Cuijpers P, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Barbui C, Bertolini F, Cabello M, Cadorin C, Downes N, Franzoi D, Gasior M, Gray B, Melchior M, van Ommeren M, Palantza C, Purgato M, van der Waerden J, Wang S, Sijbrandij M. COVID-19 and common mental health symptoms in the early phase of the pandemic: An umbrella review of the evidence. PLoS Med. 2023;20:e1004206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 30.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Lee B, Krishan P, Goodwin L, Iduye D, de Los Godos EF, Fryer J, Gallagher K, Hair K, O'Connell E, Ogarrio K, King T, Sarica S, Scott E, Li X, Song P, Dozier M, McSwiggan E, Stojanovski K, Theodoratou E, McQuillan R; UNCOVER group. Impact of COVID-19 mitigations on anxiety and depression amongst university students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health. 2023;13:06035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Wang H, Zhou Y, Dai P, Guan Y, Zhong J, Li N, Yu M. Anxiety symptoms and associated factors among school students after 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study in Zhejiang Province, China. BMJ Open. 2023;13:e079084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Piscoya-Tenorio JL, Heredia-Rioja WV, Morocho-Alburqueque N, Zeña-Ñañez S, Hernández-Yépez PJ, Díaz-Vélez C, Failoc-Rojas VE, Valladares-Garrido MJ. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Anxiety and Depression in Peruvian Medical Students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20:2907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Meda N, Pardini S, Rigobello P, Visioli F, Novara C. Frequency and machine learning predictors of severe depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation among university students. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2023;32:e42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Rabby MR, Islam MS, Orthy MT, Jami AT, Hasan MT. Depression symptoms, anxiety, and stress among undergraduate entrance admission seeking students in Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1136557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Lew B, Huen J, Yu P, Yuan L, Wang DF, Ping F, Abu Talib M, Lester D, Jia CX. Associations between depression, anxiety, stress, hopelessness, subjective well-being, coping styles and suicide in Chinese university students. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0217372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 20.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Kavvadas D, Kavvada A, Karachrysafi S, Papaliagkas V, Chatzidimitriou M, Papamitsou T. Stress, Anxiety, and Depression Levels among University Students: Three Years from the Beginning of the Pandemic. Clin Pract. 2023;13:596-609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Alwhaibi M, Alotaibi A, Alsaadi B. Perceived Stress among Healthcare Students and Its Association with Anxiety and Depression: A Cross-Sectional Study in Saudi Arabia. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;11:1625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Dos Santos WO, Juliano VAL, Chaves FM, Vieira HR, Frazao R, List EO, Kopchick JJ, Munhoz CD, Donato J Jr. Growth Hormone Action in Somatostatin Neurons Regulates Anxiety and Fear Memory. J Neurosci. 2023;43:6816-6829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Murga C, Cabezas R, Mora C, Campos S, Núñez D. Examining associations between symptoms of eating disorders and symptoms of anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation, and perceived family functioning in university students: A brief report. Int J Eat Disord. 2023;56:783-789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Serrano IMA, Cuyugan AMN, Cruz K, Mahusay JMA, Alibudbud R. Sociodemographic characteristics, social support, and family history as factors of depression, anxiety, and stress among young adult senior high school students in metro Manila, Philippines, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1225035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Agyapong B, Shalaby R, Wei Y, Agyapong VIO. Can ResilienceNHope, an evidence-based text and email messaging innovative suite of programs help to close the psychological treatment and mental health literacy gaps in college students? Front Public Health. 2022;10:890131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Chan HWQ, Sun CFR. Irrational beliefs, depression, anxiety, and stress among university students in Hong Kong. J Am Coll Health. 2021;69:827-841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Hosen I, Al-Mamun F, Mamun MA. Prevalence and risk factors of the symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress during the COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob Ment Health (Camb). 2021;8:e47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Peng P, Hao Y, Liu Y, Chen S, Wang Y, Yang Q, Wang X, Li M, Wang Y, He L, Wang Q, Ma Y, He H, Zhou Y, Wu Q, Liu T. The prevalence and risk factors of mental problems in medical students during COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2023;321:167-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 56.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Gselamu L, Ha K. Attitudes towards suicide and risk factors for suicide attempts among university students in South Korea. J Affect Disord. 2020;272:166-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Iglhaut L, Primbs R, Kaubisch S, Koppenhöfer C, Piechaczek CE, Keim PM, Kloek M, Feldmann L, Schulte-Körne G, Greimel E. Evaluation of a web-based information platform on youth depression and mental health in parents of adolescents with a history of depression. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2024;18:7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Deng Z, Zeng X, Wang H, Bi W, Huang Y, Fu H. Causal relationship between major depressive disorder, anxiety disorder and constipation: a two-sample Mendelian randomization study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2024;24:434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Gong W, Guo P, Li Y, Liu L, Yan R, Liu S, Wang S, Xue F, Zhou X, Yuan Z. Role of the Gut-Brain Axis in the Shared Genetic Etiology Between Gastrointestinal Tract Diseases and Psychiatric Disorders: A Genome-Wide Pleiotropic Analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2023;80:360-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Tarar ZI, Farooq U, Zafar Y, Gandhi M, Raza S, Kamal F, Tarar MF, Ghouri YA. Burden of anxiety and depression among hospitalized patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a nationwide analysis. Ir J Med Sci. 2023;192:2159-2166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Reyes-Martínez S, Segura-Real L, Gómez-García AP, Tesoro-Cruz E, Constantino-Jonapa LA, Amedei A, Aguirre-García MM. Neuroinflammation, Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis, and Depression: The Vicious Circle. J Integr Neurosci. 2023;22:65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |