Published online Aug 6, 2016. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v7.i3.463

Peer-review started: February 23, 2016

First decision: March 30, 2016

Revised: May 8, 2016

Accepted: June 14, 2016

Article in press: June 16, 2016

Published online: August 6, 2016

Processing time: 111 Days and 18.6 Hours

The aim of this case series was to retrospectively examine the symptom response of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C) patients administered an herbal extract in a real-world setting. Twenty-four IBS-C patients in a community office practice were provided a combination over-the-counter dietary supplement composed of quebracho (150 mg), conker tree (470 mg) and M. balsamea Willd (0.2 mL) extracts (Atrantil™) and chose to take the formulation for a minimum of 2 wk in an attempt to manage their symptoms. Patient responses to the supplement were assessed by visual analogue scale (VAS) for abdominal pain, constipation and bloating at baseline and at 2 wk as part of standard-of-care. Patient scores from VAS assessments recorded in medical chart data were retrospectively compiled and assessed for the effects of the combined extract on symptoms. Sign tests were used to compare changes from baseline to 2 wk of taking the extract. Significance was defined as P < 0.05. Twenty-one of 24 patients (88%) responded to the dietary supplement as measured by individual improvements in VAS scores for abdominal pain, bloating and constipation symptoms comparing scores prior to administration of the extract against those reported after 2 wk. There were also significant improvements in individual as well as mean VAS scores after 2 wk of administration of the combined extract compared to baseline for abdominal pain [8.0 (6.5, 9.0) vs 2.0 (1.0, 3.0), P < 0.001], bloating [8.0 (7.0, 9.0) vs 1.0 (1.0, 2.0), P < 0.001] and constipation [6.0 (3.0, 8.0) vs 2.0 (1.0, 3.0), P < 0.001], respectively. In addition, 21 of 24 patients expressed improved quality of life while taking the formulation. There were no reported side effects to administration of the dietary supplement in this practice population suggesting excellent tolerance of the formulation. This pilot retrospective analysis of symptom scores from patients before and after consuming a quebracho/conker tree/M. balsamea Willd extract may support the formulation’s use in IBS-C.

Core tip: Irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C) is a diagnosis by exclusion which is defined by abdominal pain accompanied by reduced stool frequency and painful, hard bowel movements. Gas and bloating may also be present in many patients with this condition suggesting a role in fermentation of food producing gas by bacteria in the gut. Safe tannin byproducts from wineries used in cows to reduce gas that can impair milk and meat production are combined with saponins, shown to be antibacterial and promote intestinal motility, and peppermint oil for abdominal pain in this combination extract (Atrantil™) to manage key IBS-C symptoms.

- Citation: Brown K, Scott-Hoy B, Jennings LW. Response of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation patients administered a combined quebracho/conker tree/M. balsamea Willd extract. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2016; 7(3): 463-468

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v7/i3/463.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v7.i3.463

One third of diagnosed irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) in the United States is constipation predominant and includes symptoms of abdominal pain, bloating, and constipation[1]. Women experience IBS symptoms about twice as frequently as men[2]. Irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C) has a huge impact on quality of life and productivity especially in women[3] with one investigator suggesting that IBS patients have worse health-related quality of life compared to patients with diabetes and end-stage renal disease[4]. The symptom-driven quality of life altering condition can be due to the production of gas (hydrogen, methane) which causes bloating and contributes to alterations in motility in IBS-C patients. Gas production has been linked to the presence of methanogenic archaebacteria[5,6]. Methane production has been found to be associated with delayed transit time[7,8]. Individuals diagnosed with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) also produce more hydrogen and methane which can lead to abdominal pain and constipation[9]. Fiber supplements[10] and probiotics[11] as well as drugs like rifaximin, neomycin[12], laxatives[13,14], lubiprostone[15], and linaclotide[16] all have variable effects in patients with IBS-C. There is still a need for safe agents to support GI health in patients with IBS-C.

Atrantil™, a dietary supplement composed of Quebracho, Conker Tree and M. balsamea Willd extracts, has been shown against placebo to statistically improve constipation and bloating in IBS-C subjects[17]. Quebracho extract contains tannins which are large delocalized flavonoid structures that have been used safely in wine for decades[18]. Tannins potentially have dual function[19]: They act as molecular “sponges” for excess hydrogen and methane[20] as well as disrupt and destroy bacterial lipid bilayers. Conker tree extract contains escins, also known as saponins. Saponins act as an antimicrobial agents, promote intestinal motility[21] and directly reduce methane production/emission[22,23]. M. balsamea Willd extract contains peppermint oil which has been shown to reduce abdominal pain and discomfort[11].

Patients from a single, community physician practice, who had failed to respond to conventional therapy, chose to take a recommended over-the-counter dietary supplement composed of quebracho, conker tree and M. balsamea Willd extracts in attempt to manage symptoms of abdominal pain, bloating and constipation associated with IBS-C. Their medical chart responses were retrospectively analyzed for improvement in symptomology.

Patient charts were retrospectively examined from a single physician’s practice in this case report of 24 IBS-C patients who took the dietary supplement, Atrantil™ [quebracho (150 mg), conker tree (470 mg) and M. balsamea Willd (0.2 mL) extracts], after experiencing incomplete management of symptoms with other therapies. The quebracho extract has a 80%-82% polyphenol content with 72%-74% soluble tannins, primarily consisting by of profisetinidin subunits as part of trimeric, tetrameric and pentameric condensed tannins (about 75%) determined by MALDI-TOF and 1H- and 13C-NMR fingerprint analysis. The Conker Tree extract is standardized to 20% saponin content by UV-Visible spectrophotometry and high performance thin layer chromatography (HPTLC) densitometry. Finally, pure peppermint oil content from M. balsamea Willd was determined by specific gravity, angular rotation and refractive index (USP29).

No IRB review or oversight was required in this analysis according to the terms of the United States Department of Health and Human Service’s Policy for Protection of Human Research Subjects at 45 CFR and 46.101(b) since the data already existed in patient medical charts and this data was accumulated retrospectively. There was no experimentation on patients. The dietary supplement was recommended to patients who chose to take the formulation after failing to respond to other treatments. The patients in this analysis were diagnosis with IBS-C for at least 6 mo prior to enrollment into the study (according to Rome III criteria) and had a history of uncontrolled symptoms of abdominal pain, bloating and constipation. Patients were previously on the FODMAP diet, probiotics and/or traditional drug treatments. The combined extract was administered for two weeks. Patient response to the combined extract was assessed by visual analogue scale (VAS) at baseline (before administration) and after 2 wk [End of Analysis (EOA)] for abdominal pain, bloating, and constipation as part of standard-of-care. The median and the 25th and 75th percentiles, the interquartile range (IQR), were used to summarize the scores. Sign tests, which make no assumptions about the shape of the distribution, were used to compare changes over time. Significance was defined as P < 0.05. Changes in therapy for rescue due to increased symptoms and side effects were also noted. All patients consented to have their data published.

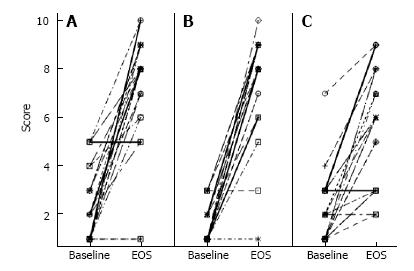

The patients in this retrospective chart analysis (n = 24) ranged in age from 18 to 58. The population consisted of 2 men and 22 women with a racial composition of 21 Caucasian, 2 Hispanic or Latino, as well as 1 African American. There were also various co-morbidities of gastroesophageal reflux disease, rosacea, hypertension and fatigue, which did not contribute to their gastrointestinal condition. Patients were not taking any other therapies for IBS-C or SIBO when they were first administered the combined extract. By EOA, 21 out of 24 patients had responded with improved VAS scores for abdominal pain (Figure 1A), bloating (Figure 1B), and constipation (Figure 1C).

Overall, 88% of this gastroenterology practice population which had incomplete relief with traditional therapies responded to the combined herbal extract in the dietary supplement. A comparison of mean VAS scores for abdominal pain, bloating and constipation from baseline and EOA showed a significant improvement in all three symptoms over time for the entire population while on the combined extract (Table 1).

| Symptom | Baselinemedian (IQR) | EOAmedian (IQR) | EOA-baselinemedian (IQR) | P value |

| Abdominal pain | 2.0 (1.0, 3.0) | 8.0 (6.5, 9.0) | 5.5 (3.5, 7.0) | < 0.001 |

| Bloating | 1.0 (1.0, 2.0) | 8.0 (7.0, 9.0) | 6.5 (5.5, 8.0) | < 0.001 |

| Constipation | 2.0 (1.0, 3.0) | 6.0 (3.0, 8.0) | 4.0 (2.0, 5.5) | < 0.001 |

A response rate of 88% in IBS-C patients with a significant reduction in abdominal pain, bloating, and constipation suggests very good efficacy in this difficult to treat population. No rescue medication was needed during the 2 wk course of the observation and there were no reported adverse events suggesting excellent tolerance of the herbal extract.

Over 90% of IBS patients suffer from bloating which is directly linked to abdominal pain and distention[24]. These symptoms may be caused by SIBO or dysbiosis. No matter the cause, current therapeutics may not meet the needs of all patients. In a 10 wk study of rifaximin (550 mg TID) vs placebo in IBS patients, for example, the overall response rate was 40.8% vs 31.2% for placebo (P = 0.01)[25]. Using a similar retrospective medical chart analysis to the one utilized in this study, Yang et al[26] found a 69% response rate to rifaximin and 44% to neomycin in 98 lactulose breath test positive IBS patients. Another study found that patients who had an abnormal lactulose breath test with follow up testing (n = 47) when treated with neomycin had a 75% response rate[9]. Even with the success of antibiotic treatment, relapse remains a significant problem in SIBO patients[27].

Other agents are also used for constipated patients. In an open-label extension study of lubiprostone (n = 522), a locally acting chloride channel activator, demonstrated a response rate of about 40%, but about 32% of participants in the extension part of the study required a rescue medication[28]. Adverse effects for lubiprostone include dose-related nausea and dyspnea with chest tightness. For idiopathic constipation, lanaclotide demonstrated about 50% response rate for pain and increase in stool frequency compared to placebo responses of about 35% and about 25%, respectively[29,30]. About 20% of patients on linaclotide experienced diarrhea compared to about 3% in the placebo groups.

Nutritional approaches to IBS-C and SIBO include dietary fiber, the FODMAP (Fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols) diet and probiotics. Fiber can be effective in managing constipation, but bloating, distension, flatulence and cramping may limit the use of insoluble fiber. Water intake with fiber is very important. In patients with IBS, soluble fiber, such as psyllium may be effective, but insoluble fiber can exacerbate symptoms[10,31]. The FODMAP diet has been found to decrease abdominal pain and bloating, but adherence to the diet can be difficult[32]. Probiotics containing Bifidobacterium lactis DN-173 010, Lactobacillus casei Shirota, and Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 demonstrate favorable data on defecation frequency and stool consistency[33]. Other approaches are still needed for patients with IBS-C and SIBO.

In a 2 wk randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study of patients previously diagnosed with IBS-C (n = 16), there were significant improvements in the average constipation (P = 0.0034), bloating (P < 0.001) and constipation plus bloating scores (P < 0.001) in the Atrantil™ group compared to no improvement for the placebo arm[17]. There were also no reports of AEs over the 2 wk period. In this retrospective chart analysis of 24 patients administered Atrantil™, there was a 3.2-fold average improvement in abdominal pain, a 5.1-fold improvement in bloating, and a 2.7-fold improvement in constipation. Twenty-one of 24 patients responded to therapy for an overall response rate of 88%. There were also no reported side effects to therapy. These consistent data suggest that the combined herbal extracts of quebracho, conker tree and M. balsamea Willd present in Atrantil™ decreases symptoms associated with IBS-C.

The quebracho extract consists primarily of tannins, the same used in for over 50 years to change the taste and texture of wine[18]. Tannins are highly delocalized structures which are able to act as antiradical sinks or antioxidants[34]. Tannins also directly limit methanogenesis by inhibiting the growth of methane producing bacteria by reducing the availability of hydrogen[35]. Conker Tree extract contains the antimicrobial saponins[21] which can also reduce the production as well as emission of methane presumably by limiting hydrogen availability[22,23]. Saponins have also been found to improve intestinal motility in mice[36] and improve passage of gas, GI sounds and bowel movements in postoperative colorectal surgery patients[37]. The M. balsamea Willd extract contains peppermint oil which has been found to help reduce abdominal pain[11]. Peppermint oil has also been shown to act as an antispasmodic attenuating contractile responses to acetylcholine, histamine, 5-hydroxytryptamine, and substance P[38,39]. The combination of these extracts in Atrantil™ may have limited the availability of hydrogen by preventing growth of microorganisms which produce methane that contributes to abdominal pain, bloating and constipationin this IBS-C patient population. In addition, the combination extracts may also improve motility and intestinal transit time.

Though this pilot medical chart analysis was performed in a relatively small number of patients (n = 24) with IBS-C, the response rate was very high (88%). The small number of patients, the fact that they were drawn from a single site and the uncontrolled nature of the analysis with only therapy adherent individuals being evaluated are limitations for this study. Still, the statistical improvement in symptoms of abdominal pain, bloating and constipation found in this retrospective study are consistent with a previous placebo-controlled clinical trial[17]. Therefore, the results of this small open-label study of Atrantil™ may be a useful intervention for patients with IBS-C and SIBO. Further, larger double-blind, placebo-controlled studies are needed to confirm these results.

The primary symptoms experienced by this clinical practice cohort of patients were abdominal pain, bloating and constipation.

Significant improvements in abdominal pain, bloating and constipation were found after a 2 wk administration of the mixed quebracho/conker Tree/M. balsamea Willd extracts in Atrantil™ in irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C) patients.

Organic causes of constipation were excluded first for all patients in this practice cohort which were then diagnosed with IBS-C according to Rome III criteria for functional constipation including at least two of the following: (1) two or fewer defecations in the toilet per week; (2) At least one episode of fecal incontinence per week; (3) History of retentive posturing or excessive volitional stool retention; (4) History of painful or hard bowel movements; (5) Presence of a large fecal mass in the rectum; and (6) History of large diameter stools which may obstruct the toilet.

Since there is no tissue or blood marker for IBS-C, no laboratory testing was performed in this case series.

Twenty-four IBS-C patients in a single clinical practice were provided a combination over-the-counter dietary supplement composed of quebracho (150 mg), conker tree (470 mg) and M. balsamea Willd (0.2 mL) extracts (Atrantil™) and chose to take the formulation for a minimum of 2 wk in an attempt to manage abdominal pain, bloating and constipation.

This case series is a follow up to a well-controlled pilot clinical study in IBS-C patients (Brown et al, 2015) testing the same dietary supplement in IBS-C patients composed of quebracho (150 mg), conker tree (470 mg) and M. balsamea Willd (0.2 mL) extracts (Atrantil™).

All terms in this case series are standard and used in the field of gastroenterology.

This case series shows the utility of a dietary supplement in drug refractory IBS-C patients formulated to act as a molecular sink for gas ions in the intestine, a bacteriostatic agent to inhibit the impact of bacteria in the small bowel and a component to aid in abdominal discomfort.

The limitations of this case series were that it was in a relatively small cohort of patients biased for compliance in consuming the therapeutic agent in an uncontrolled setting. This case series in combination with the previously published pilot clinical trial suggests promise for Atrantil™ in IBS-C patients with the caveat that a larger, well-controlled study is needed.

Specialty Type: Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Country of Origin: United States

Peer-Review Report Classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Gomes A S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Su AM, Shih W, Presson AP, Chang L. Characterization of symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome with mixed bowel habit pattern. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;26:36-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lovell RM, Ford AC. Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:712-721.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1251] [Cited by in RCA: 1414] [Article Influence: 108.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Everhart JE, Ruhl CE. Burden of digestive diseases in the United States part II: lower gastrointestinal diseases. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:741-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 335] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Mönnikes H. Quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45 Suppl:S98-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pimentel M, Mayer AG, Park S, Chow EJ, Hasan A, Kong Y. Methane production during lactulose breath test is associated with gastrointestinal disease presentation. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:86-92. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Attaluri A, Jackson M, Valestin J, Rao SS. Methanogenic flora is associated with altered colonic transit but not stool characteristics in constipation without IBS. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1407-1411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Pimentel M, Lin HC, Enayati P, van den Burg B, Lee HR, Chen JH, Park S, Kong Y, Conklin J. Methane, a gas produced by enteric bacteria, slows intestinal transit and augments small intestinal contractile activity. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290:G1089-G1095. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Triantafyllou K, Chang C, Pimentel M. Methanogens, methane and gastrointestinal motility. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;20:31-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pimentel M, Chow EJ, Lin HC. Eradication of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3503-3506. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Moayyedi P, Quigley EM, Lacy BE, Lembo AJ, Saito YA, Schiller LR, Soffer EE, Spiegel BM, Ford AC. The effect of fiber supplementation on irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1367-1374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Lacy BE, Lembo AJ, Saito YA, Schiller LR, Soffer EE, Spiegel BM, Quigley EM. American College of Gastroenterology monograph on the management of irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109 Suppl 1:S2-26; quiz S27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 403] [Cited by in RCA: 405] [Article Influence: 36.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pimentel M, Chang C, Chua KS, Mirocha J, DiBaise J, Rao S, Amichai M. Antibiotic treatment of constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:1278-1285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chapman RW, Stanghellini V, Geraint M, Halphen M. Randomized clinical trial: macrogol/PEG 3350 plus electrolytes for treatment of patients with constipation associated with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1508-1515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kamm MA, Mueller-Lissner S, Wald A, Richter E, Swallow R, Gessner U. Oral bisacodyl is effective and well-tolerated in patients with chronic constipation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:577-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Drossman DA, Chey WD, Johanson JF, Fass R, Scott C, Panas R, Ueno R. Clinical trial: lubiprostone in patients with constipation-associated irritable bowel syndrome--results of two randomized, placebo-controlled studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:329-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Videlock EJ, Cheng V, Cremonini F. Effects of linaclotide in patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation or chronic constipation: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1084-1092.e3; quiz e68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Brown K, Scott-Hoy B, Jennings . Efficacy of a Quebracho, Conker Tree, and M. balsamea Willd blended extract in patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. J Gasterenterol Hepatol Res. 2015;4:1762-1767. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bertoldi D, Santato A, Paolini M, Barbero A, Camin F, Nicolini G, Larcher R. Botanical traceability of commercial tannins using the mineral profile and stable isotopes. J Mass Spectrom. 2014;49:792-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Nakayama T, Hashimoto T, Kajiya K, Kumazawa S. Affinity of polyphenols for lipid bilayers. Biofactors. 2000;13:147-151. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Hook SE, Wright AD, McBride BW. Methanogens: methane producers of the rumen and mitigation strategies. Archaea. 2010;2010:945785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in RCA: 276] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Fu F, Hou Y, Jiang W, Wang R, Liu K. Escin: inhibiting inflammation and promoting gastrointestinal transit to attenuate formation of postoperative adhesions. World J Surg. 2005;29:1614-1120. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Guo YQ, Liu JX, Lu Y, Zhu WY, Denman SE, McSweeney CS. Effect of tea saponin on methanogenesis, microbial community structure and expression of mcrA gene, in cultures of rumen micro-organisms. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2008;47:421-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Li W. 2012; Using Saponins to Reduce Gaseous Emissions from Steers. |

| 24. | Ringel Y, Williams RE, Kalilani L, Cook SF. Prevalence, characteristics, and impact of bloating symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:68-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Pimentel M, Lembo A, Chey WD, Zakko S, Ringel Y, Yu J, Mareya SM, Shaw AL, Bortey E, Forbes WP. Rifaximin therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome without constipation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:22-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 690] [Cited by in RCA: 691] [Article Influence: 49.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yang J, Lee HR, Low K, Chatterjee S, Pimentel M. Rifaximin versus other antibiotics in the primary treatment and retreatment of bacterial overgrowth in IBS. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:169-174. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Pimentel M, Morales W, Chua K, Barlow G, Weitsman S, Kim G, Amichai MM, Pokkunuri V, Rook E, Mathur R. Effects of rifaximin treatment and retreatment in nonconstipated IBS subjects. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:2067-2072. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chey WD, Drossman DA, Johanson JF, Scott C, Panas RM, Ueno R. Safety and patient outcomes with lubiprostone for up to 52 weeks in patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:587-599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Lavins BJ, Shiff SJ, Kurtz CB, Currie MG, MacDougall JE, Jia XD, Shao JZ, Fitch DA. Linaclotide for irritable bowel syndrome with constipation: a 26-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate efficacy and safety. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1702-1712. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Rao S, Lembo AJ, Shiff SJ, Lavins BJ, Currie MG, Jia XD, Shi K, MacDougall JE, Shao JZ, Eng P. A 12-week, randomized, controlled trial with a 4-week randomized withdrawal period to evaluate the efficacy and safety of linaclotide in irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1714-124; quiz p.1725. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Eswaran S, Muir J, Chey WD. Fiber and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:718-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 24.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Halmos EP, Power VA, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR, Muir JG. A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:67-75.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 810] [Cited by in RCA: 829] [Article Influence: 75.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Chmielewska A, Szajewska H. Systematic review of randomised controlled trials: probiotics for functional constipation. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:69-75. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Hagerman AE, Riedl KM, Jones GA, Sovik KN, Ritchard NT, Hartzfeld PW, Riechel TL. High molecular weight plant polyphenolics (tannins) as biological antioxidant. J Agric Food Chem. 1998;46:1887-1892. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 906] [Cited by in RCA: 711] [Article Influence: 26.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Tavendale MH, Meagher LP, Pacheco D, Walker N, Attwood GT, Sivakumaran S. Methane production from in vitro rumen incubations with Lotus pedunculatus and Medicago sativa, and effects of extractable condensed tannin fractions on methanogenesis. Animal Feed Sci Technol. 2005;123:403-419. |

| 36. | Matsuda H, Li Y, Yoshikawa M. Effects of escins Ia, Ib, IIa, and IIb from horse chestnuts on gastrointestinal transit and ileus in mice. Bioorg Med Chem. 1999;7:1737-1741. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Xie Q, Zong X, Ge B, Wang S, Ji J, Ye Y, Pan L. Pilot postoperative ileus study of escin in cancer patients after colorectal surgery. World J Surg. 2009;33:348-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | de Sousa AA, Soares PM, de Almeida AN, Maia AR, de Souza EP, Assreuy AM. Antispasmodic effect of Mentha piperita essential oil on tracheal smooth muscle of rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;130:433-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Khanna R, MacDonald JK, Levesque BG. Peppermint oil for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48:505-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |