Published online Oct 15, 2017. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v8.i10.455

Peer-review started: February 7, 2017

First decision: March 28, 2017

Revised: April 15, 2017

Accepted: May 3, 2017

Article in press: May 5, 2017

Published online: October 15, 2017

Processing time: 253 Days and 22.3 Hours

To compare the safety and efficacy or 3 basal-bolus regimens of neutral protamine hagedorn (NPH)/regular insulin in the management of inpatient hyperglycemia.

We randomized 105 patients with blood glucose levels between 140 and 400 mg/dL to a basal-bolus regimen of NPH insulin given once (n = 30), twice (n = 40) or three times (n = 35) daily, in addition to pre-meal regular insulin. Major outcomes included were differences in glycemic control, frequency of hypoglycemia and total insulin dose.

NPH insulin given in a once-daily regimen was associated with better glycemic control (58.3%) compared to twice daily (42.4%) and three times daily (48.9) regimens (P = 0.031). The frequency of hypoglycemia was similar between the three groups (2.0%, 0.7% and 1.2%, P = 0.21). The mean insulin dose at discharge was 0.48 ± 0.14 U/kg in the once-daily group compared to 0.69 ± 0.28 in the twice-daily, and 0.65 ± 0.20 in the three times daily regimens (P < 0.001).

NPH insulin administered in a once-daily regimen resulted in improvement in glycemic control with similar rates of hypoglycemia compared to a twice-daily and a three times-daily regimen. Further studies are needed to evaluate whether this regimen could be implemented in all hospitalized patients with hyperglycemia.

Core tip: In this parallel randomized clinical trial, we compared various insulin regimes. Administration of one-daily neutral protamine hagedorn (NPH) regimen improved glycemic control with similar rates compared to a twice-daily and a three times daily regimen. Furthermore, the use of NPH insulin in a once-daily regimen is associated with lower requirements as well as lower variability in the insulin dose during follow up.

- Citation: Quintanilla-Flores DL, González-González JG, García-De la Cruz G, Tamez-Pérez HE. Neutral protamine hagedorn/regular insulin in the treatment of inpatient hyperglycemia: Comparison of 3 basal-bolus regimens. World J Diabetes 2017; 8(10): 455-463

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v8/i10/455.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v8.i10.455

Hyperglycemia is a common finding in hospitalized patients with a prevalence of approximately 25%[1]. It can be secondary to undiagnosed diabetes, stress hyperglycemia pharmacological agents, glucocorticoids or poorly controlled diabetes. For every 2 patients hospitalized with a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2), there is one with previously undetected hyperglycemia[2]. In addition, about 90% of hospitalized patients with diabetes have hyperglycemia (> 200 mg/dL) and in 20% of these patients hyperglycemia persists for 3 or more days[3].

Poor glycemic control has been established as a risk factor for poor clinical outcome and mortality[2,4]. Glucose levels between 140-180 mg/dL are associated with a reduction in mortality, systemic infections, risk of multi-organ failure, bacetermia, critical illness polyneuropathy, inflammation and hospital stay[4-6]. Subcutaneous insulin, given as a daily basal-bolus, is the only agent that has proven efficacy and safety for glycemic control in general medical and surgical patients with hyperglycemia.

Despite its benefits, treatment of hyperglycemia still remains delayed. The fear of causing hypoglycemia[3] and the clinical inertia of no treatment remain the main barriers for initiating insulin. Physicians commonly use a sliding-scale regimen until stabilization of glucose levels[7]; however, a study by Umpierrez et al[8] found that a basal-bolus insulin algorithm was more effective than a sliding-scale regimen for glucose control.

The use of a basal-bolus regimen with both insulin analogs and a neutral protamine hagedorn (NPH)/regular insulin mix has been studied. Similar rates of glucose control and hypoglycemic events were found with both regimens making them suitable for the treatment of inpatient hyperglycemia[4,9,10]. Current guidelines do not specify whether the NPH dose of insulin should be administered in a once daily, twice daily or three times daily regimen during hospitalization. The twice daily regimen has been traditionally used in previous clinical trials as the standard regimen of reference, suggesting it to be the most physiologic form of administration. Accordingly, we conducted a prospective, randomized non-blinded study to compare the efficacy and safety of three basal-bolus regimens of NPH/regular insulin for the control of hyperglycemia in patients admitted to an internal medicine ward.

Subjects were men and women aged > 16 years, admitted to medical services with a persistent blood glucose level > 140 mg/dL and with an expected stay ≥ 48 h. Exclusion criteria included individuals with type 1 diabetes mellitus, parenteral nutrition, blood glucose levels ≥ 400 mg/dL at screening, diabetic ketoacidosis or nonketotic hyperosmolar syndrome, clinically relevant hepatic disease, glomerular filtration rate ≤ 30 mL/min, pregnancy, terminal disease, and/or inability to provide informed consent. Patients were eliminated when there was poor adherence to the administration of insulin or glucose measurements (defined as ≤ 70% of total insulin doses or glucose measurements), discharge or death within the first 48 h of enrollment or when glucocorticoids were given during follow up.

We developed a single center, open-label, randomized, parallel comparative study in the Internal Medicine Department, at the “Dr. José Eleuterio González” University Hospital from September 2013 to September 2015. It was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki revised in 2008 and approved by the local ethical committees. All subjects provided informed consent. Participants were randomized using an online randomization generator available at http://www.randomization.com. A database including the sequential order of randomization was generated in an Excel file. Both the enrollment and follow-up of the included subjects was performed by the members of the research team in cooperation with the attending physicians. The protocol was registered in clinicalrials.gov (Trial registry number: NCT02758522).

All patients were managed by physicians of an internal medicine residency program. The primary care teams decided on the treatment for all other medical problems for which the patients were admitted. Oral antidiabetic drugs were suspended during hospitalization. HbA1c was measured during the first day of hospital stay. Post-discharge follow up was not included as part of this study.

Patients were randomized to receive NPH insulin either once-daily, twice-daily or three times-daily. The twice-daily regimen was also included as the reference regimen, since it has been traditionally used in previous trials when NPH/Regular insulin is administered in hospitalized patients. The starting dose was calculated according to body mass index (BMI): 0.3 U/kg for BMI < 18 kg/m2, 0.4 U/kg for BMI 18-24.9 kg/m2, 0.5 U/kg for BMI 25-29.9 kg/m2 and 0.6 U/kg for BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2. The resulting dose was fractioned to be given 60% as basal insulin (NPH) and 40% as prandial (regular) insulin. NPH insulin once-daily was administered subcutaneously before breakfast; in the twice-daily regimen it was given before breakfast and before dinner; and in the three times daily regimen it was administered before each meal. Regular insulin was given in three equally divided doses before each meal. A sliding-scale regimen of supplemental regular insulin was given in addition to the scheduled pre-meal insulin when blood glucose levels were ≥ 140 mg/dL. When the patient was not able to eat, the dose of regular insulin was held until meals were resumed. Furthermore, when glucose values between 70 mg/dL and 100 mg/dL were detected before meals, the corresponding dose of insulin was suspended in order to prevent hypoglycemia.

Hypoglycemia was defined as a glucose level < 70 mg/dL. Severe hypoglycemia was defined as a glucose level < 40 mg/dL or the need of assistance. All blood glucose values less than 70 mg/dL were treated with 20 g oral carbohydrate (fruit or juice) or 25 g of intravenous glucose depending on the neurologic state. The dose of total daily insulin was reduced by 20% when an episode of hypoglycemia was reported.

Blood glucose was determined four times a day: Before each meal and at bedtime using a glucose meter. The insulin dose was adjusted daily according to glucose values: If blood glucose was not in the target range of fasting glucose ≤ 140 mg/dL and random glucose was ≤ 180 mg/dL (nonfasting glucose measured at any time during the day), the total insulin dose was increased by 20%, fractioned in 60% NPH and 40% rapid insulin.

The primary outcome was to determine the differences in glycemic control between the treatment groups. Glycemic control was defined as the proportion of patients that achieved fasting glucose between 70-140 mg/dL and random glucose levels of < 180 mg/dL during the whole hospital stay. Mean overall, fasting and random, glucoses were also used to assess differences in glycemic control between the three regimens. They were established as the average of daily repeated measurements taken each day during hospitalization. Secondary outcomes included differences in the percentage of glucose levels in the hypoglycemic range (overall and severe hypoglycemia), and the total insulin dose required during follow up and at discharge to achieve glycemic control and differences in mortality and hospital stay.

Based on previous data about glycemic control in hospitalized patients, we calculated that 93 subjects (31 per group) had the power to provide an 80% chance of detecting, with an α error rate of 5%, a difference greater than 30% in glycemic control between the 3 regimens. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 19.0 software package. For the continuous variables, differences were examined by ANOVA or Kruskal Wallis as needed. The χ2 test was used for categorical data. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

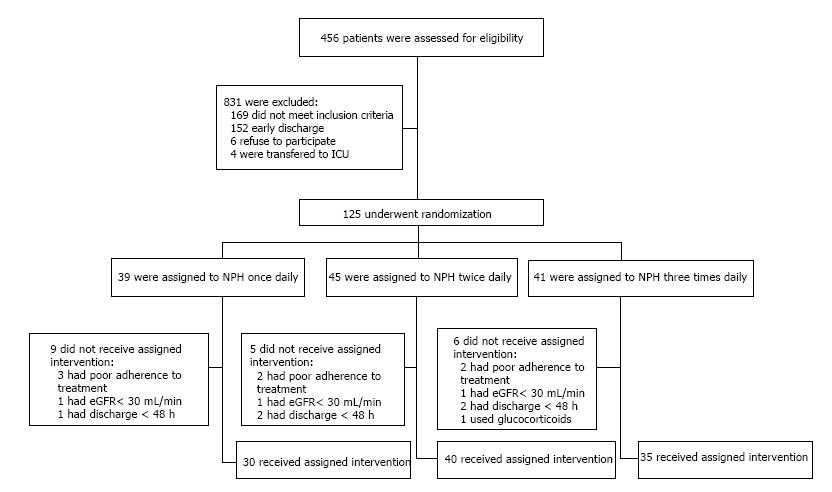

A total of 105 patients were finally included for analysis, 85 of them with known type 2 diabetes mellitus. Figure 1 shows the enrollment of the patients. No between-treatment differences were apparent at baseline, except that patients in the once-daily regimen had a shorter duration of diabetes (P = 0.01) and were less prone to insulin use before hospitalization (P = 0.01) (Table 1). Metformin and glibenclamide were the only oral anti-diabetic drugs used by the patients prior hospitalization. These drugs were drugs were suspended during hospitalization. Over 19% subjects had an unrecognized history of diabetes mellitus, and more than half had received prior therapy with insulin before hospitalization. The most common diagnoses on admission were coronary artery disease, infections and neoplastic disorders. Pneumonia was the most common cause of infection, followed by urinary tract infections and diarrhea. None of the subjects with sepsis were included. The median duration of treatment was 6 (2-14) d, and the median hospital stay was 8 (2-36) d. No deaths were reported among the study subjects. Diabetes related chronic complications were not evaluated in this study.

| NPH × 1 | NPH × 2 | NPH × 3 | P | |

| n | 30 | 40 | 35 | |

| Age (yr, X ± DS) | 60 ± 15 | 58 ± 15 | 54 ± 14 | 0.39 |

| Gender (% female) | 12 (40) | 20 (50) | 22 (63) | 0.18 |

| Unknown history of T2DM, n (%) | 12 (40.0) | 4 (10.0) | 4 (11.4) | 0.01 |

| Duration of T2DM (yr), med (min-max) | 5 (0-30) | 15 (0-30) | 10 (0-25) | 0.01 |

| Prior T2DM therapy, n (%) | 0.02 | |||

| None | 17 (56.7) | 7 (17.5) | 9 (25.7) | |

| Oral antidiabetics | 9 (30.0) | 20 (50.0) | 15 (42.9) | |

| Insulin | 4 (13.3) | 21 (52.5) | 15 (42.9) | |

| Insulin + oral antidiabetics | - | 8 (20.0) | 4 (11.4) | |

| Charlson score, med (min-max) | 3 (1-9) | 3 (1-5) | 3 (1-7) | 0.14 |

| Hospitalization diagnosis, n (%) | ||||

| Coronary artery disease | 7 (23.3) | 13 (32.5) | 11 (31.4) | 0.69 |

| Infectious disease | 5 (16.7) | 13 (32.5) | 9 (25.7) | 0.35 |

| Neoplasm | 7 (23.3) | 3 (7.5) | 2 (5.7) | 0.051 |

| Dysrhythmias | 4 (13.3) | 1 (2.5) | 2 (5.7) | 0.23 |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 4 (13.3) | 1 (2.5) | 3 (8.6) | 0.24 |

| Pancreatitis | 2 (6.7) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (2.9) | 0.68 |

| Stroke | - | 2 (5.0) | 1 (2.9) | 0.78 |

| Other | 1 (3.3) | 6 (15.0) | 6 (15.0) | 0.88 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 8 (26.7) | 12 (31.6) | 15 (42.9) | 0.33 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), X ± DS | 26.4 ± 5.2 | 27.5 ± 5.6 | 27.5 ± 5.3 | 0.65 |

| HbA1c (%), X ± DS | 9.5 ± 2.4 | 10.2 ± 2.4 | 10.4 ± 2.8 | 0.45 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 80 ± 26 | 88 ± 26 | 90 ± 30 | |

| Admission blood glucose (mg/dL), X ± DS | 272 ± 84 | 308 ± 62 | 306 ± 70 | 0.08 |

| Glomerular filtration rate1 (mL/min), X ± DS | 77.3 ± 32.9 | 86.9 ± 30.1 | 92.4 ± 23.4 | 0.13 |

| Treatment follow-up (d), med (min-max) | 6 (2-14) | 6 (2-14) | 7 (2-14) | 0.41 |

| Hospital stay (d), med (min-max) | 8 (4-31) | 8 (2-28) | 10 (4-36) | 0.39 |

Mean baseline glucose levels were similar between the three groups. Mean glucose levels during follow up were 160, 190 and 179 mg/dL for the once-daily, twice-daily and three times-daily regimens, respectively (P = 0.02). The percentage of patients within the target range of glycemic control were 58% in patients treated with the once-daily regimen, 42% in the twice-daily regimen and 49% in the three times-daily regimen (P = 0.03). In the post-hoc analysis patients treated with the once-daily regimen had greater improvement in glycemic control than those treated with the twice-daily regimen (P = 0.03), maintaining significant differences only in random glucose samples (P = 0.02). There was no significant difference between the subjects in the once-daily regimen and the three times-daily regimen. Nearly half of the patients achieved had least 50% of the glucose measures of the day within the target ranges (P = 0.39), and about one quarter achieved 75% within the target ranges (P = 0.09) (Table 2).

| NPH × 1, n = 30 | NPH × 2, n = 40 | NPH × 3, n = 35 | P | |

| Mean glucose (mg/dL) | 160.3 ± 36.4 | 190.4 ± 48.0 | 178.7 ± 44.2 | 0.02 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 149.2 ± 36.5 | 175.9 ± 54.6 | 169.5 ± 43.2 | 0.054 |

| Random glucose (mg/dL) | 164.4 ± 38.2 | 198.9 ± 53.2 | 181.0 ± 47.8 | 0.013 |

| Glycemic control (%) | 58.3 ± 25.3 | 42.4 ± 24.3 | 48.9 ± 24.1 | 0.031 |

| Fasting glucose (%) | 47.0 ± 35.0 | 34.0 ± 30.8 | 42.5 ± 32.3 | 0.253 |

| Random glucose (%) | 62.8 ± 25.9 | 45.5 ± 25.2 | 52.8 ± 26.6 | 0.024 |

| 50% daily glucoses within target range (%) | 53.0 ± 29.4 | 43.8 ± 29.5 | 48.1 ± 30.6 | 0.455 |

| Time to achieve 50% of daily glucoses within target range (h) | 48.9 ± 27.8 | 61.2 ± 33.9 | 59.6 ± 47.0 | 0.438 |

| 75% daily glucoses within target range (%) | 27.4 ± 26.5 | 14.3 ± 21.1 | 21.8 ± 25.5 | 0.069 |

| Time to achieve 75% of daily glucoses within target range (h) | 76.8 ± 48.4 | 84.8 ± 57.3 | 99.8 ± 85.1 | 0.904 |

| Insulin dose (UI/kg) | ||||

| Basal | 0.44 ± 0.13 | 0.51 ± 0.18 | 0.52 ± 0.15 | 0.1 |

| At discharge | 0.48 ± 0.14 | 0.69 ± 0.28 | 0.65 ± 0.20 | < 0.001 |

| Δ Insulin dose | 0.04 ± 0.10 | 0.19 ± 0.22 | 0.13 ± 0.18 | 0.004 |

The once-daily regimen provided glycemic control when the duration of diabetes was < 10 years, the patient received treatment with insulin before hospitalization, the HbA1c was > 9% (75 mmol/mol), there was an absence of infection and the BMI was ≥ 25 kg/m2 (Table 3).

| NPH × 1, n = 30, (%) | NPH × 2, n = 40, (%) | NPH × 3, n = 35, (%) | P | |

| DM ≤ 10 yr | ||||

| Overall | 62.1 ± 24.8 | 47.3 ± 25.6 | 50.4 ± 23.4 | 0.17 |

| Fasting glucose | 53.7 ± 31.9 | 35.2 ± 30.5 | 42.1 ± 32.0 | 0.03 |

| Random glucose | 65.9 ± 24.9 | 51.1 ± 27.2 | 55.8 ± 28.2 | 0.25 |

| Pre-hospital insulin | ||||

| Overall | 77.5 ± 12.4 | 37.6 ± 23.9 | 37.7 ± 26.1 | 0.012 |

| Fasting glucose | 39.5 ± 35.5 | 29.7 ± 27.5 | 24.1 ± 25.1 | 0.59 |

| Random glucose | 91.8 ± 7.5 | 41.0 ± 26.1 | 46.0 ± 31.2 | 0.01 |

| Baseline glucose > 300 mg/dL | ||||

| Overall | 52.9 ± 24.5 | 37.7 ± 26.9 | 40.8 ± 20.0 | 0.36 |

| Fasting glucose | 38.1 ± 35.6 | 33.6 ± 34.8 | 36.0 ± 26.7 | 0.94 |

| Random glucose | 57.4 ± 22.4 | 38.7 ± 26.1 | 42.7 ± 22.5 | 0.21 |

| HbA1c > 9% (75 mmol/mol) | ||||

| Overall | 55.2 ± 24.0 | 33.7 ± 22.6 | 45.8 ± 28.1 | 0.06 |

| Fasting glucose | 43.0 ± 33.9 | 25.5 ± 27.3 | 40.4 ± 31.0 | 0.18 |

| Random glucose | 60.0 ± 22.3 | 36.6 ± 23.1 | 48.2 ± 28.3 | 0.04 |

| Absence of infectious disease | ||||

| Overall | 61.0 ± 24.1 | 39.8 ± 25.1 | 50.9 ± 25.6 | 0.01 |

| Fasting glucose | 50.8 ± 34.0 | 34.2 ± 32.8 | 44.1 ± 35.8 | 0.22 |

| Random glucose | 65.4 ± 25.4 | 41.8 ± 25.3 | 54.3 ± 26.5 | 0.01 |

| Glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min | ||||

| Overall | 62.8 ± 25.3 | 42.0 ± 29.7 | 45.2 ± 16.7 | 0.20 |

| Fasting glucose | 40.0 ± 34.7 | 35.1 ± 32.8 | 31.2 ± 20.3 | 0.87 |

| Random glucose | 71.9 ± 27.3 | 44.4 ± 30.4 | 55.4 ± 29.5 | 0.14 |

| Body mass index, dex ± 29.52 | ||||

| Overall | 63.4 ± 22.8 | 44.1 ± 25.2 | 48.0 ± 23.3 | 0.03 |

| Fasting glucose | 47.1 ± 35.0 | 39.9 ± 34.0 | 42.1 ± 30.4 | 0.78 |

| Random glucose | 69.9 ± 23.1 | 45.6 ± 25.1 | 50.8 ± 23.9 | 0.01 |

Mean total insulin daily doses were significantly higher in both the three times-daily and the twice-daily regimens compared with that in the once-daily regimen (P < 0.001). Furthermore the once-daily regimen was associated with less variability in insulin dose during the entire study, as shown in the Δ of insulin dose (P = 0.004) (Table 2).

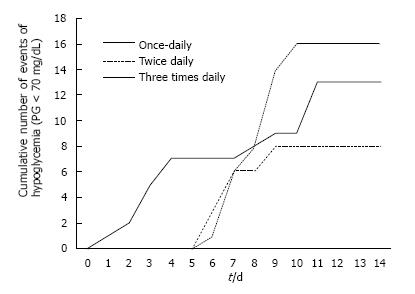

Figure 2 shows the cumulative incidence of hypoglycemic events. Fewer events occurred with the twice-daily regimen, followed by the once-daily regimen, and the three times-daily regimen (P = 0.004). Expressed as rate of hypoglycemia (proportion of events/total glucoses), the differences did not reach statistical significance. A total of 492 glucose readings were performed in the once-daily regimen; of these 13 (2.0%) were < 70 mg/dL. Of the 754 glucose readings in the twice-daily regimen 8 (0.7%) were < 70 mg/dL. Finally, of the 745 glucose readings of the three times-daily regimen 16 (1.2%) were < 70 mg/dL (P = 0.21). Only one episode of severe hypoglycemia was documented in the twice-daily regimen.

A higher proportion of patients in the three times-daily regimen experienced hypoglycemia before dinner (P = 0.04). The insulin dose of presentation of an event of hypoglycemia was significantly lower in the once-daily regimen (0.38 ± 0.13 U/kg) compared to the twice-daily (0.67 ± 0.17 U/kg) and the three times-daily [0.94 ± 0.48 (U/kg)] regimens (P < 0.001) (Table 4). When adjusting the rate of hypoglycemia according to different variables, the once-daily regimen proved to be associated with higher rates when HbA1c < 9% (75 mmol/mol) (rate 4.3%) compared to the twice daily regimen (rate 1.1%) and the three times daily regimen (rate 0%) (P = 0.04).

| NPH × 1, n = 30 | NPH × 2, n = 40 | NPH × 3, n = 35 | P | |

| Hypoglycemic events (n) | 13 | 8 | 16 | |

| Severe hypoglycemia | – | 1 | – | 0.45 |

| Rate of hypoglycemia (%), (X ± SD)1 | 2.0 ± 3.8 | 0.7 ± 2.3 | 1.2 ± 3.1 | 0.21 |

| Time to the first episode (d), (X ± SD) | 6.2 ± 4.0 | 7.1 ± 1.2 | 8.2 ± 1.2 | 0.14 |

| Insulin dose at event (IU/kg), (X ± SD) | 0.38 ± 0.13 | 0.67 ± 0.17 | 0.94 ± 0.48 | < 0.001 |

| Time of presentation, n (%) | ||||

| Before breakfast | 5 (38.5) | 2 (25.0) | 1 (6.2) | 0.11 |

| Before supper | 3 (23.1) | 3 (37.5) | 2 (12.5) | 0.37 |

| Before dinner | 2 (15.4) | – | 7 (43.8) | 0.04 |

| Bedtime | 3 (23.1) | 3 (37.5) | 6 (37.5) | 0.43 |

NPH insulin administered in a once-daily regimen resulted in improvement in glycemic control with similar rates of hypoglycemia compared to a twice-daily and a three times-daily regimen. This superiority is of particular importance when the duration of diabetes is less than 10 years, HbA1c > 9% (75 mmol/mol), there is pre-hospital insulin use, an absence of infection during hospitalization and the patient has a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2. Furthermore, the use of NPH insulin in a once-daily regimen is associated with lower insulin requirements and lower variability in the insulin dose during follow up.

According to previous studies[4,9,10], glycemic control with levels < 140 mg/dL can be achieved in up to 48%-74% of patients with rates of hypoglycemia of 2%-3.3% when scheduled NPH/regular insulin in a twice-daily protocol is used in non-critically ill patients. We found differences in glucose levels and lower rates of hypoglycemia when a twice-daily regimen was implemented. This could be explained by differences in the target glucose values in previous studies as well as the variability in the basal characteristics of our patients, who had a longer duration of diabetes, higher HbA1c levels and a higher proportion of individuals using insulin prior to randomization. Furthermore, our population included only Hispanic subjects, which according to Bueno et al[10] tend to be significantly leaner, have worse glycemic control and higher HbA1c levels on admission as well as more hypoglycemic events compared to United States population.

In the ambulatory setting, the addition of a single bedtime injection of NPH insulin in those patients who remain poorly controlled with oral agents has been explored[11]. Extrapolated to the hospital setting, this is the first prospective randomized study that evaluates the efficacy of NPH insulin given in a once-daily regimen to inpatients with hyperglycemia. Of note is the observation that compared to the other two study groups, NPH insulin given in a once-daily regimen was associated with a lower dose of total insulin at the end of the study as well as with less variability in the insulin dose during the study period. Despite these differences in total insulin dose, this regimen was related to better glycemic control in selected patients as well as similar rates of hypoglycemia. This measure should be recommended especially when the duration of diabetes is < 10 years, the patients have been treated with insulin prior to hospitalization, HbA1c is > 9% (75 mmol/mol), an absence of infection, and the patient’s BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2.

Compared to insulin analogs, variability in the serum levels of NPH insulin, secondary to intermediate duration of action and a peak activity at 4-6 h after injection, have questioned its safety and efficacy in the treatment of hyperglycemia. NPH insulin has proved similar rates of glycemic control with a tendency to higher risk of hypoglycemia and greater glycemic variability when it is compared with glargine or detemir[4,11]. Some other studies have concluded similar rates of glycemic control and hypoglycemia[9]. In an attempt to equalize the effect of insulin analogs in terms of glycemic variability, we tried to split the total dose of NPH insulin into 3 equal doses administered during the day. We hypothesized that by splitting the total dose of NPH insulin, we could achieve a flat curve of serum NPH insulin levels similar to that observed with insulin analogs. On the contrary, we found higher rates of a cumulative number of hypoglycemia events and higher doses of insulin required to achieve similar rates of glycemic control. It seems that this measure should not be used as a first-line option in the management of inpatient hyperglycemia. It might be useful when higher doses of total insulin are required during the follow-up of patients treated with a once or twice daily regimen.

Controversy exists whether insulin analogs, such as glargine and detemir, are associated with better glycemic control and a lower risk of hypoglycemia compared to NPH insulin in the management of hospitalized hyperglycemia in the non-crically ill. Yeldandi et al[4] showed similar rates of glycemic control with a lower risk of hypoglycemia when insulin glargine was used compared to NPH insulin in a basal/bolus scheme. In the DEAN trial, similar improvements in glycemic control with no differences in hypoglycemia events were found with the use detemir once daily and aspart before meals compared to NPH/regular insulin in a twice daily regimen[9]. Bueno et al[10] showed similarly significant improvement in glycemic control without increasing the prevalence of overall hypoglycemia, with higher prevalence of severe hypoglycemia when twice daily NPH/regular insulin was used compared to once daily glargine and glulisine before meals (0.83% vs 0.25%, P = 0.01)[10]. In institutions with low- and middle-income resources, such as ours, access to insulin analogs is barely possible. It seems that the benefits of optimal glycemic control outweigh the slightly increased risk of severe hypoglycemia, which of note does not exceed 1% in overall prevalence. We consider that the implementation of protocols of glycemic control that include the use of NPH insulin in the basal regimen are still needed to reduce the complications of severe hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia in hospitalized patients.

There are several limitations in our study to consider: (1) we did not assess the daily oral caloric intake of our patients and the stratification of risk factors of hypoglycemia. Higher risk of hypoglycemia has been observed among subjects with variability in their caloric intake, comorbidities such as liver disease and renal disease, sepsis, malnutrition and drugs such as quinolones and β-agonists[12]; (2) our study was powered to evaluate differences in glycemic control and risk of hypoglycemia instead of mortality and clinical outcomes. Despite the fact that 16% of the randomized patients were lost during follow up, the minimum of 93 subjects to maintain the statistical power of our study was accomplished. In addition, only patients who completed the study were included for the analysis. We believe that in spite of this limitation, our findings provide reliable information to draw conclusions; (3) we included patients with a longer duration of diabetes, higher HbA1c levels on admission and a greater proportion of patients on insulin before hospitalization compared to previous studies. This could underestimate the rates of glycemic control in our patients compared to that of previous studies which included subjects with lower risk of severe hyperglycemia as shown by Pasquel et al[13] who proved that patients with higher HbA1c levels have lower odds of having optimal glucose control among hospitalized patients; (4) as it is shown in Table 2, patients in the once-daily regimen had a shorter duration of diabetes and were less prone to insulin use before hospitalization. Additionally, the proportion of patients with unknown history of diabetes was substantially greater in this group as compared to others, the rate of hypoglycemia tended to be higher and the meantime insulin dose at the event was lower, indicating probable greater insulin sensitivity. These features could explain the better glycemic response and lower insulin dose in once-daily regimen group instead of the once-daily regimen itself; (5) we are aware that the comparison of repetitive measurements could be a better strategy for statistical analysis, however we decided to use average glucose levels since this is the way it has been presented in previous studies that compare different schemes of treatment of inpatient hyperglycemia; and (6) even though subjects were treated with the insulin regimen during the whole hospitalization, the median duration of days for follow up in our study was 6 (2-14) d. This period of maximum 14 d of follow up permitted an adequate titration of insulin dose with achievement of glycemic target in all patients and avoided bias linked to long hospital stay related complications.

In summary, NPH insulin administered in a once-daily regimen resulted in improvement in glycemic control with similar rates of hypoglycemia compared to a twice-daily and a three times-daily regimen. This superiority is of particular importance when the duration of diabetes is less than 10 years, HbA1c is > 9% (75 mmol/mol), there is pre-hospital insulin use, an absence of infection during hospitalization and the patient’s BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2. Furthermore, the use of NPH insulin in a once-daily regimen is associated with lower requirements as well as lower variability in the insulin dose during follow up. Whether this superiority in glycemic control and insulin dose was related to greater insulin sensitivity among the study subjects in the once-daily regimen needs to be reassessed in further studies. NPH insulin in a three times-daily regimen might not be recommended as a first-line option, because it is associated with a higher cumulative incidence of hypoglycemia and higher insulin doses in spite of an equivalent glycemic control. In this parallel randomized clinical trial, we compared various insulin regimes. Administration of once-daily NPH regimen improved glycemic control with similar rates compared to a twice-daily and a three times daily regimen. Furthermore, the use of NPH insulin in a once-daily regimen is associated with lower requirements as well as lower variability in the insulin dose during follow up.

Despite its limitations, our findings could be useful for changing algorithms for the treatment of inpatient hyperglycemia in addition to current health policies. Further studies are needed to estimate whether NPH insulin in a once-daily regimen can be incorporated as an option in certain populations among the hospitalized patients.

We wish to thank Sergio Lozano-Rodríguez, MD, for the English translation and his critical reading of the manuscript.

Poor glycemic control among hospitalized patients has been established as a risk factor for poor clinical outcome and mortality. The use of a basal-bolus regimen with both insulin analogs and a neutral protamine hagedorn (NPH)/regular insulin has proven efficacy and safety for glycemic control in general medical and surgical patients with hyperglycemia.

In institutions with low- and middle-income resources, access to insulin analogs is barely possible. The implementation of protocols of glycemic control that include the use of NPH insulin in the basal regimen are still needed to reduce the complications of severe hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia in hospitalized patients.

In this study the authors showed that NPH insulin administered in a once-daily regimen results in improvement in glycemic control with similar rates of hypoglycemia compared to a twice-daily and a three times-daily regimen. Furthermore, it is associated with lower requirements as well as lower variability in the insulin dose during follow up.

This study provides evidence of an alternative regimen of basal/bolus insulin among the hospitalized patients with diabetes.

Glycemic control was defined as the achievement of fasting glucose between 70-140 mg/dL and random glucose levels of < 180 mg/dL. Hypoglycemia was defined as a glucose level < 70 mg/dL. Severe hypoglycemia was defined as a glucose level < 40 mg/dL or the need of assistance.

This is an overall good quality article.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Endocrinology and metabolism

Country of origin: Mexico

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C ,C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Fatima SS, Klimontov V, Tung TH, Zhao JB S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | DeSantis AJ, Schmeltz LR, Schmidt K, O’Shea-Mahler E, Rhee C, Wells A, Brandt S, Peterson S, Molitch ME. Inpatient management of hyperglycemia: the Northwestern experience. Endocr Pract. 2006;12:491-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Maynard G, Lee J, Phillips G, Fink E, Renvall M. Improved inpatient use of basal insulin, reduced hypoglycemia, and improved glycemic control: effect of structured subcutaneous insulin orders and an insulin management algorithm. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:3-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Schnipper JL, Ndumele CD, Liang CL, Pendergrass ML. Effects of a subcutaneous insulin protocol, clinical education, and computerized order set on the quality of inpatient management of hyperglycemia: results of a clinical trial. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:16-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yeldandi RR, Lurie A, Baldwin D. Comparison of once-daily glargine insulin with twice-daily NPH/regular insulin for control of hyperglycemia in inpatients after cardiovascular surgery. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2006;8:609-616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Juneja R, Foster SA, Whiteman D, Fahrbach JL. The nuts and bolts of subcutaneous insulin therapy in non-critical care hospital settings. Postgrad Med. 2010;122:153-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Van den Berghe G, Wouters PJ, Bouillon R, Weekers F, Verwaest C, Schetz M, Vlasselaers D, Ferdinande P, Lauwers P. Outcome benefit of intensive insulin therapy in the critically ill: Insulin dose versus glycemic control. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:359-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 856] [Cited by in RCA: 764] [Article Influence: 34.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tamez-Pérez HE, Quintanilla-Flores DL, Proskauer-Peña SL, González-González JG, Hernández-Coria MI, Garza-Garza LA, Tamez-Peña AL. Inpatient hyperglycemia: Clinical management needs in teaching hospital. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2014;1:176-178. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Umpierrez GE, Smiley D, Zisman A, Prieto LM, Palacio A, Ceron M, Puig A, Mejia R. Randomized study of basal-bolus insulin therapy in the inpatient management of patients with type 2 diabetes (RABBIT 2 trial). Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2181-2186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 488] [Cited by in RCA: 459] [Article Influence: 25.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Umpierrez GE, Hor T, Smiley D, Temponi A, Umpierrez D, Ceron M, Munoz C, Newton C, Peng L, Baldwin D. Comparison of inpatient insulin regimens with detemir plus aspart versus neutral protamine hagedorn plus regular in medical patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:564-569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bueno E, Benitez A, Rufinelli JV, Figueredo R, Alsina S, Ojeda A, Samudio S, Cáceres M, Argüello R, Romero F. Basal-bolus regimen with insulin analogues versus human insulin in medical patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial in latin america. Endocr Pract. 2015;21:807-813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Riddle MC, Rosenstock J, Gerich J. The treat-to-target trial: randomized addition of glargine or human NPH insulin to oral therapy of type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:3080-3086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1173] [Cited by in RCA: 1043] [Article Influence: 47.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Moghissi ES, Korytkowski MT, DiNardo M, Einhorn D, Hellman R, Hirsch IB, Inzucchi SE, Ismail-Beigi F, Kirkman MS, Umpierrez GE. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Diabetes Association consensus statement on inpatient glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1119-1131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 916] [Cited by in RCA: 885] [Article Influence: 55.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pasquel FJ, Gomez-Huelgas R, Anzola I, Oyedokun F, Haw JS, Vellanki P, Peng L, Umpierrez GE. Predictive Value of Admission Hemoglobin A1c on Inpatient Glycemic Control and Response to Insulin Therapy in Medicine and Surgery Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:e202-e203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |