Published online Jun 27, 2025. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v17.i6.107160

Revised: April 8, 2025

Accepted: May 27, 2025

Published online: June 27, 2025

Processing time: 101 Days and 15.7 Hours

Insulin resistance is a cardiometabolic risk factor characterized by elevated insulin levels. It is associated with fatty liver disease and elevated liver function tests (LFT) in cross-sectional studies, but data from cohort studies are scarce.

To investigate the association between insulin and pathological LFT, liver disease, and cirrhosis in a population-based retrospective cohort study.

Anthropometric and cardiometabolic factors of 857 men and 1228 women from prospective cohort studies were used. LFT were obtained at two time points 8 years to 24 years after baseline. Liver disease diagnoses were obtained from nationwide registries. The association between insulin levels and the development of elevated LFT or liver disease and cirrhosis was analyzed.

Total follow-up was 54054 person-years for women and 27556 person-years for men. Insulin levels were positively correlated with elevated LFT during follow-up, whereas physical activity and coffee consumption were negatively correlated. Individuals with both insulin levels in the upper tertile and alcohol consumption above MASLD thresholds had an increased risk for both liver disease, adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) of 4.3 (95%CI: 1.6-14.6) and cirrhosis (aHR = 4.8, 95%CI: 1.6-14.6).

This population-based study provides evidence that high insulin levels are a risk factor for development of elevated liver enzymes and clinically manifest liver disease. The results support the concept of metabolic dysfunction associated liver disease.

Core Tip: Insulin resistance is a cardiometabolic risk factor. There is a paucity of cohort studies examining the effect of insulin on liver function tests and liver disease. This cohort study followed 2085 participants for up to 24 years. High insulin levels were associated to elevated liver enzymes and clinical manifest liver disease.

- Citation: Schult A, Mehlig K, Svärdsudd K, Wallerstedt S, Björkelund C, Hansson PO, Zetterberg H, Kaczynski J. Association between insulin and liver function tests, liver disease and cirrhosis in population-based cohorts with long term follow-up. World J Hepatol 2025; 17(6): 107160

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v17/i6/107160.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v17.i6.107160

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is the most common liver disease in most parts of the world, affecting more than a quarter of the world's population[1,2]. MASLD encompasses a spectrum from bland steatosis to steatohepatitis, fibrosis, and cirrhosis. Due to its increasing prevalence, MASLD is expected to become the leading cause of liver transplantation within the next decade[3].

The prevalence of MASLD exceeds 50% in populations with type 2 diabetes[4,5]. Several studies suggested MASLD being the hepatic manifestation of the metabolic syndrome[6,7] with insulin resistance as the core component[8]. Elevated insulin levels are the hallmark of insulin resistance[9] and the association between insulin resistance and elevated liver function tests (LFT) has been demonstrated in cross-sectional studies[10,11]. However, few population-based studies with long-term follow-up have examined the association between insulin and LFTs or liver disease.

The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between insulin levels, the development of elevated LFT and manifest liver disease in two cohorts of men and women in whom we have previously shown that body mass index (BMI) in men and waist-to-hip ratio in women are risk factors for incident liver cirrhosis[12,13]. Based on data from cross-sectional studies, we hypothesized that individuals with elevated insulin levels would be more likely to develop pathological LFT and to be diagnosed with of chronic liver disease during follow-up.

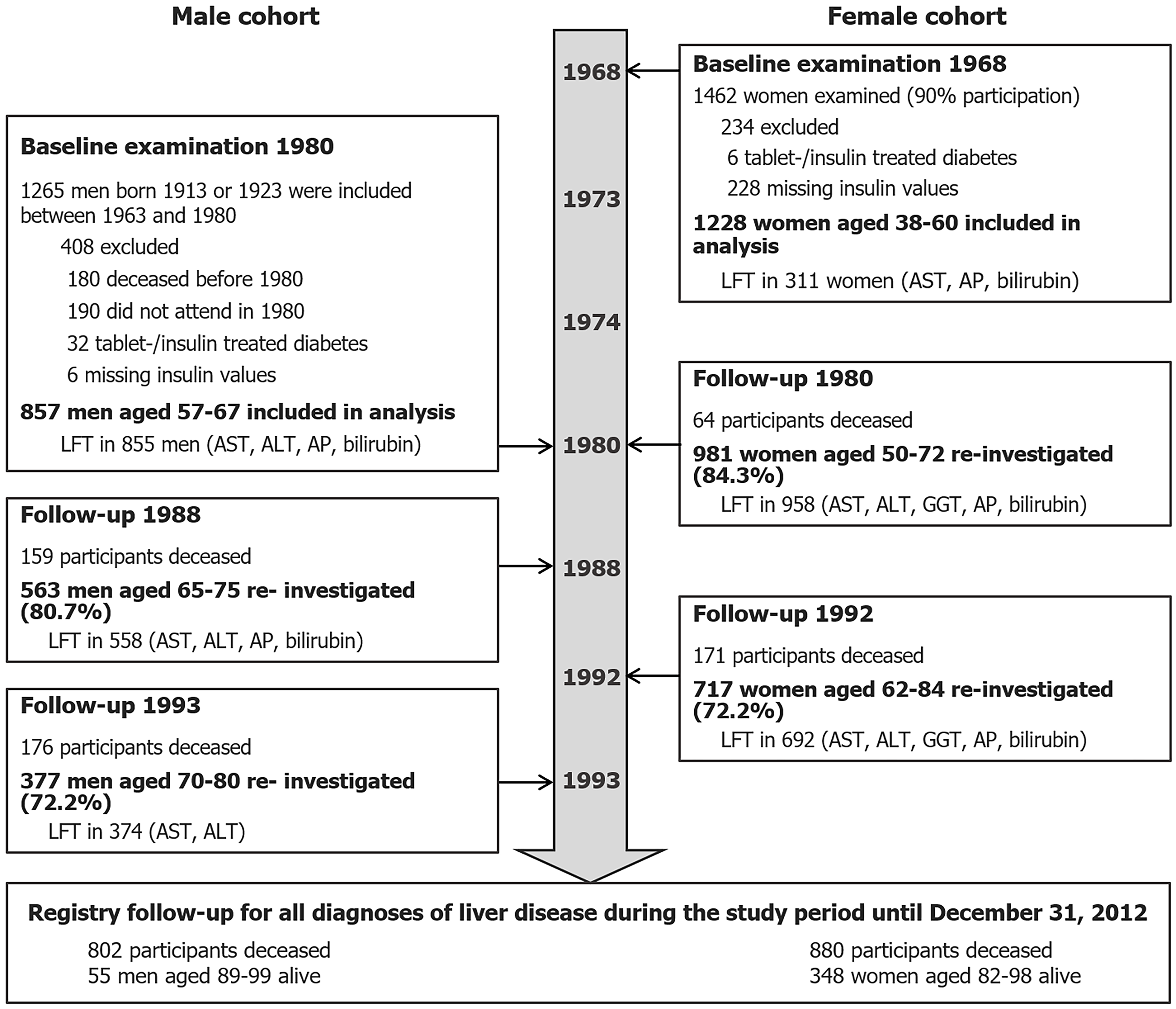

The study populations derived from prospective cohort studies starting during the 1960’s in Gothenburg, the second largest city in Sweden with a population of more than 400000 at the time[14]. As the main purpose of these studies was to investigate cardiovascular disease, numerous cardiometabolic, anthropometric, and socioeconomic factors were examined. The cohorts are described below and summarized in Figure 1.

In 1963 a longitudinal population-based study of men aged 50 years was started. A representative sample of all men born in 1913 and living in the city of Gothenburg was invited to participate. A similar cohort was recruited in 1973[15]. The cohorts have been followed up at regular intervals. The examination of 1980 including measurement of fasting serum insulin represents the baseline for the current study. Of the 895 men who participated, 32 men with tablet-treated or insulin-treated diabetes mellitus were excluded and insulin samples were not collected from 6 individuals. A total of 857 men were included in the analyses.

The population study of women in Gothenburg began in 1968. A representative sample of 1622 women between the ages of 38 years and 60 years of age was randomly selected from the general population and 1462 women (90.1%) agreed to participate. Participation rates at follow-up examinations in 1980 and 1992 were 78.9% and 57.2%, respectively[13]. The baseline examination for the female cohort was performed in 1968. Participants with tablet- or insulin-treated diabetes mellitus (n = 6) and without insulin samples (n = 228) were excluded from the analysis. The remaining 1228 women constitute the female cohort of this study.

Participants’ leisure-time physical activity (LTPA) was categorized as “sedentary lifestyle”, “moderate activity” and “regular exercise” based on a questionnaire[16]. Coffee consumption was recorded as cups per day.

Information on drinking habits was obtained using a structured interview that asked about intake of beer, wine, and liquor in a semi-quantitative manner. Response categories included seldom or never, monthly, weekly, several times a week and daily. The actual average daily alcohol intake in grams was calculated by multiplying the frequency of consumption by the quantity of the beverage and the specific alcohol content. We assumed daily intake to mean 2 drinks per day, intake several times a week to mean 4 drinks per week, weekly intake to mean 2 drinks per week, and monthly intake to mean an average of 2 drinks per month. We further assumed that an alcoholic drink is equivalent to 33 cl of beer at 5% alcohol content, 15 cl of wine at 13% alcohol content, and 4 cl of spirits at 40% alcohol content[17]. At some examinations more detailed information on alcohol consumption was obtained. When possible, this information was used to calculate the amount of alcohol consumed.

Participants were categorized as having high intake of alcohol or not according to the cut-off values for MASLD (140 g ethanol per week for women and 210 g per week for men)[18].

All baseline anthropometric measurements were taken in the morning. Body weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a balance scale, corrected for the estimated weight of clothing. Height was measured to the nearest 0.5 cm. BMI was calculated as a person's weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters.

In men, waist circumference and hip circumference were measured to the nearest centimeter at the level of the umbilicus with the subjects standing upright using a steel tape. For women, measurements were taken at the midpoint between the lower rib margin and the iliac crest with an accuracy of between 0.1 cm and 1 cm.

All participants underwent a complete physical examination and blood pressure (BP) was measured after 5-10 minutes of rest using a mercury sphygmomanometer with a 12 cm cuff. Participants were considered to have hypertension if they were being treated for hypertension or had a history of hypertension, or if they had either a systolic BP greater than 140 mmHg or a diastolic BP greater than 90 mmHg.

Blood samples were collected after an overnight fast for analysis of LFT, glucose, triglycerides, and cholesterol. LFT were performed in 1967, 1980, 1988 and 1993 in men and in 1968, 1980 and 1992 in women. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were analyzed by standard fluorometric methods, alkaline phosphatase (AP) and γ-glutamyltransferase by spectrophotometry and bilirubin by a coupling reaction with diazo dye in the presence of an accelerating agent.

In men, plasma insulin concentration was measured in 1980 by a double antibody method using a commercial radioimmunoassay kit (Phadebas®, Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden)[19]. In women, fasting insulin was analyzed in 2012/2013 from serum samples stored at −20 °C since 1968 (Supplementary material). Analysis was performed in the Clinical Chemistry Laboratory at Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Sweden, using Elecsys kits on a Cobas 6000 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) by certified laboratory technicians blinded to clinical data. The results were validated by comparison with values in a sub-sample of participants that had been analyzed at baseline using the same method as in men. A diagnosis of diabetes was made if the participants reported having diabetes, being currently treated for diabetes, or having a fasting glucose level of 7.0 mmol/L (126 mg/dL) or higher.

The primary outcome variable was elevated LFT during follow-up. LFT above the sex-specific upper limit of normal (Supplementary Table 1) were considered pathological. Secondary outcomes were diagnoses of liver disease and cirrhosis. Cases were identified by matching study participants using their personal identification number[20] with the hospital discharge register (HDR) and the cause of death register (CDR) at the National Board of Health and Welfare. The HDR covers principal and secondary diagnoses for all hospitalized patients. The CDR records the main causes of death and contributing conditions. Both registries have a high coverage and validity[21,22] and record all patients admitted to Swedish hospitals and the causes of death of all Swedish citizens, including those who die abroad. These registries were searched for study participants with a diagnosis of liver disease using the International Classification of Diseases (Supplementary Table 2).

Descriptive results were expressed as means and standard deviations for continuous variables and as numbers and proportions for categorical variables. Differences between men and women were tested by Mann-Whitney U test, t-test, or χ2 test as appropriate.

Cross-sectional regression analysis was performed using a linear regression model with LFT as continuous dependent variable, LTPA and smoking status as factors and insulin levels, coffee and alcohol consumption, age, and waist circumference as covariates. Because of differences in age, method of measurement and timepoint of insulin sampling, these analyses were performed separately for men and women. Results are presented as beta coefficients with 95%CI.

Univariate Cox proportional hazards analyses were performed with the primary and secondary outcome variables and insulin at baseline as the main exposure variable. Survival time was calculated from baseline to the event of interest. Cases were censored at death or at the end of follow-up (December 31, 2012). Potential confounders included alcohol and coffee consumption, smoking, anthropometric measurements, BP, sex, age at baseline and glucose, triglyceride, and cholesterol levels. Insulin was categorized into sex-specific percentiles to account for differences in year of baseline sampling, method of insulin measurement, and potential differences between the sexes. Analyses were stratified by gender.

Variables with a P value < 0.1 were considered for inclusion in a multivariable Cox regression model adjusted for sex and age. Among correlated variables reflecting the similar underlying concepts (i.e., waist circumference, body weight, or BMI as a measure of weight status) those with the lowest P value were selected.

We hypothesized a synergistic effect of alcohol and insulin on the likelihood of developing liver disease and cirrhosis. Therefore, participants were grouped according to their alcohol consumption using cut-offs for MASLD (140 g alcohol per week for women, 210 g alcohol per week for men[18]) and tertiles of insulin levels and the hazards of incident liver disease/cirrhosis were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method. Hazard ratios (HR) were calculated by Cox regression analyses including an interaction variable comparing participants with a combination of high alcohol intake and insulin levels in the upper tertile with all other combinations.

Sensitivity analyses excluded participants with elevated LFT before or at baseline examination and exclusion of patients with a diagnosis of liver disease/liver cirrhosis within 3 years of baseline.

Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Male participants were older than those in the female cohort. They had a higher alcohol consumption than women, but more women consumed an amount of alcohol above the cutoff for MASLD. Men had higher blood glucose but lower insulin levels.

| Men | Women | P value | |||

| N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | ||

| Age (years) | 857 | 64.8 (4.1) | 1228 | 47.0 (6.3) | < 0.001 |

| Alcohol (g/day) | 848 | 12.8 (18.3) | 1227 | 8.7 (11.5) | < 0.001 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 852 | 4.6 (1.1) | 1226 | 4.1 (0.8) | < 0.001 |

| Insulin (mIU/L) | 857 | 13.3 (9.7) | 1228 | 13.9 (7.1) | < 0.001 |

| Coffee (cups per day) | 855 | 3.9 (2.5) | 1227 | 4.6 (2.8) | < 0.001 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 857 | 95.3 (9.1) | 1227 | 73.7 (8.5) | < 0.001 |

| Body mass index | 856 | 25.3 (3.2) | 1228 | 24.1 (3.7) | < 0.001 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 856 | 152 (23.3) | 1228 | 134 (21.9) | < 0.001 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 855 | 84 (11.2) | 1228 | 83 (10.8) | 0.063 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 846 | 1.7 (0.9) | 1228 | 1.2 (0.6) | < 0.001 |

| Cholesterol (mmol/L) | 848 | 6.7 (1.2) | 1228 | 6.8 (1.2) | 0.020 |

| Smoking | 857 | 1227 | < 0.001 | ||

| Never smoked | 204 (23.8) | 650 (53.0) | |||

| Quit smoking | 366 (42.7) | 90(7.3) | |||

| Still smoking1 | 287(33.5) | 487(39.7) | |||

| Leisure time physical activity | 854 | 1228 | 0.014 | ||

| Sedentary | 118 (13.8) | 219 (17.8), | |||

| Moderate/regular1 | 736 (86.2) | 1009 (82.2) | |||

| Alcohol (m/f) > 210/140 g per week1 | 848 | 110 (13.0) | 1227 | 203 (16.5) | 0.029 |

| Elevated liver function test1 | 855 | 78 (9.1) | 311 | 17 (5.5) | 0.052 |

At baseline, at least one liver function test was available for 311 women [AST (n = 309), AP (n = 304) and bilirubin (n = 303)]. Of these, 17 (5.5 %) were above the upper limit of normal (Supplementary Table 1). In men, baseline LFT were available for 855 participants [AST and bilirubin (n = 853), ALT and AP (n = 852)], of which 78 (9.1%) were classified as pathological. An additional 63 men had a pathological LFT prior to baseline.

In a cross-sectional linear regression analysis adjusted for age, smoking status, alcohol intake and LTPA, baseline insulin levels were significantly associated with positive coefficients to ALT (P < 0.001) and AST (P = 0.039) in men and with negative coefficients to bilirubin (P = 0.014 in men, P = 0.018 in women). A positive association was also observed for waist circumference and transaminases in men (P < 0.001 for ALT, P = 0.039 for AST). In women, AST showed no significant associations with anthropometric or cardiometabolic risk factors. Waist circumference was positively associated with AP in both men and women (P = 0.008 and P = 0.005, respectively).

During follow-up, 177 (17.3%) women and 57 (9.8%) men had pathological LFT. In Cox regression analysis, insulin levels, alcohol consumption and waist circumference were positively associated with elevated LFT during follow-up, whereas LTPA and coffee consumption were negatively associated (Table 2). The unadjusted HR for elevated LFT for those with above median insulin levels was 1.41 (95%CI: 1.09- 1.83, P = 0.009).

| Hazard ratio | 95%CI | P value | |

| Sex (male vs female) | 0.83 | 0.61-1.12 | 0.225 |

| Insulin (mIU/L) | 1.011 | 1.00-1.03 | 0.035 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 0.99 | 0.83-1.17 | 0.986 |

| Ethanol (10 g/day) | 1.131 | 1.03-1.23 | 0.007 |

| Coffee (cups per day) | 0.921 | 0.87-0.97 | 0.004 |

| Smoking (never) | 1 | Reference | |

| Smoking (former) | 0.69 | 0.44-1.08 | 0.102 |

| Smoking (current) | 1.10 | 0.84-1-45 | 0.661 |

| Leisure time physical activity (moderate/regular vs sedentary) | 0.631 | 0.46-0.86 | 0.004 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 1.021 | 1.00-1.03 | 0.023 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 1.02 | 0.98-1.06 | 0.270 |

| Age (years) | 1.00 | 0.97-1.02 | 0.717 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 1.00 | 1.00-1.01 | 0.180 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 1.01 | 1.00-1.02 | 0.166 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 0.99 | 0.80-1.21 | 0.889 |

| Cholesterol (mmol/L) | 0.93 | 0.83-1.04 | 0.213 |

The multivariable Cox regression model was adjusted for age and sex. There was a significant correlation between waist circumference and both age and sex (correlation coefficients 0.71 and 0.77, respectively). In a linear regression with survival time as the dependent variable and possible predictors, waist circumference had a variance inflation factor of 3.0 and was not included in the model. Analysis showed that insulin, alcohol and coffee consumption, and LTPA were statistically significantly associated with elevated LFT (Table 3). A model with stepwise forward selection of variables resulted in the same final multivariable model. Using insulin as a categorical variable comparing the upper tertile to the rest, the HR was 1.34 (95%CI: 1.02-1.75, P < 0.05).

| Main analysis HR (95%CI) | Sensitivity analysis HR (95%CI) | |

| Insulin (mIU/L) | 1.02 (1.00-1.03)a | 1.02 (1.01-1.04)b |

| Ethanol (10 g/day) | 1.15 (1.05-1.25)b | 1.15 (1.04-1.26)b |

| Leisure time physical activity (moderate/regular vs sedentary lifestyle) | 0.62 (0.45-0.84)b | 0.60 (0.43-0.82)b |

| Coffee (cups per day) | 0.92 (0.87-0.97)b | 0.94 (0.89-0.99)a |

The total follow-up time was 54054 person-years for women and 27556 person-years for men. During follow-up, 802 men (93.6%) and 880 women (71.7%) deceased, and their observations were censored unless liver disease was a (contributing) cause of death. A total of 41 participants received a diagnosis of liver disease, three of which were made before the baseline examination. Excluding these, 22 women and 16 men developed liver disease, with corresponding incidence rates per 100000 person-years of 52.5 (95%CI: 33.8-78.2) in women and 114.3 (95%CI: 67.7-181.7) in men.

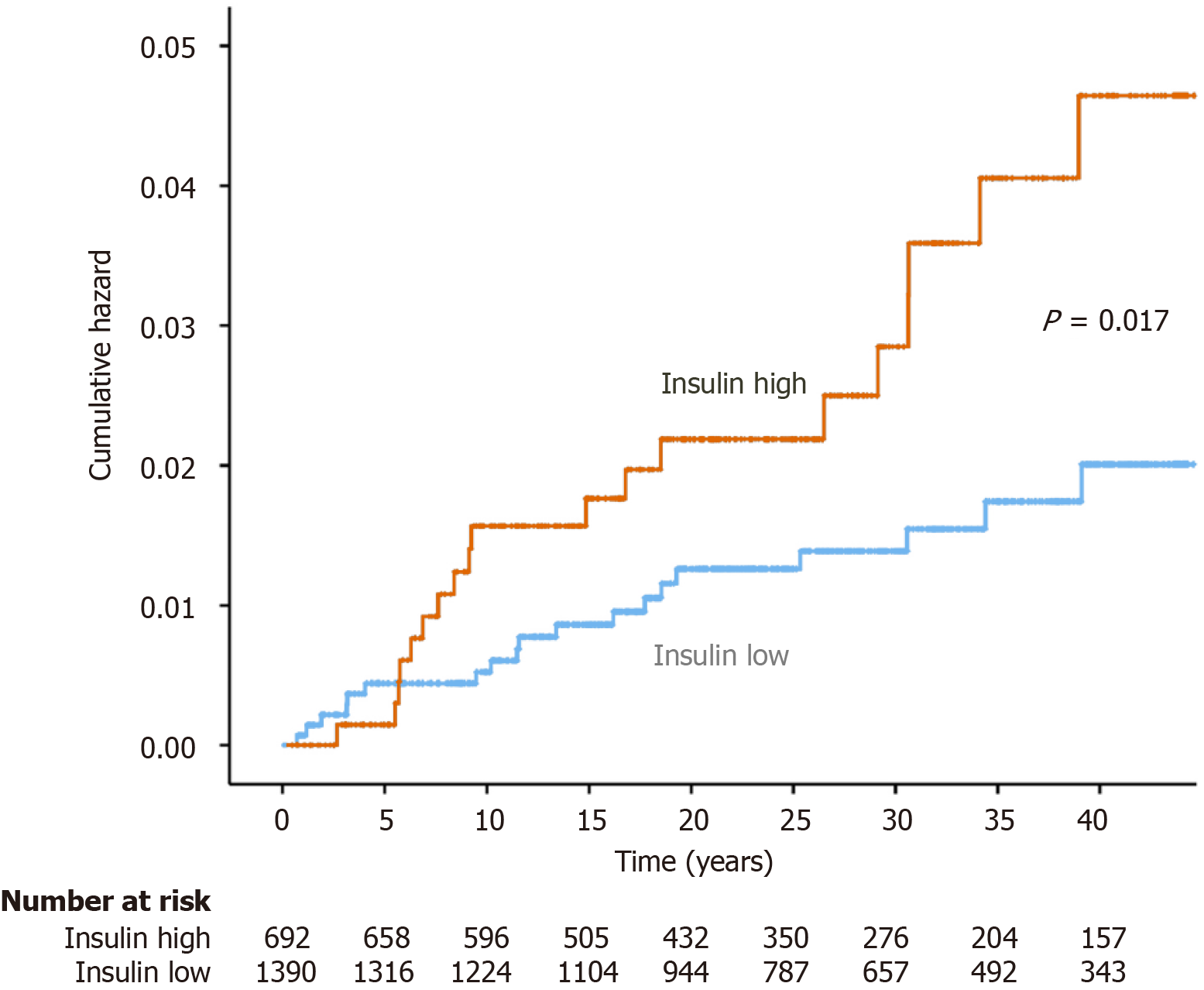

Liver disease was associated with insulin (HR = 1.03 per mIU/L, 95%CI: 1.00-1.05, P = 0.045), alcohol (HR = 1.22 per 10 g ethanol, 95%CI: 1.08-1.37, P < 0.001), waist circumference (HR = 1.05, 95%CI: 1.01-1.98, P = 0.004), male sex (HR = 2.21, 95%CI: 1.09-4.48, P = 0.027), and smoking (HR = 2.35, 95%CI: 1.23-4.46 for current smokers, P = 0.009) in univariable Cox regression analysis. The HR for incident liver disease was 2.10 (95%CI: 1.13-4.02, P = 0.02) for the upper tertile of insulin levels compared to the lower tertiles. Kaplan-Meier analysis of incident cases of liver disease showed a statistically significant difference (log-rank test, P = 0.017) between individuals within the upper tertile of insulin levels or below (Figure 2).

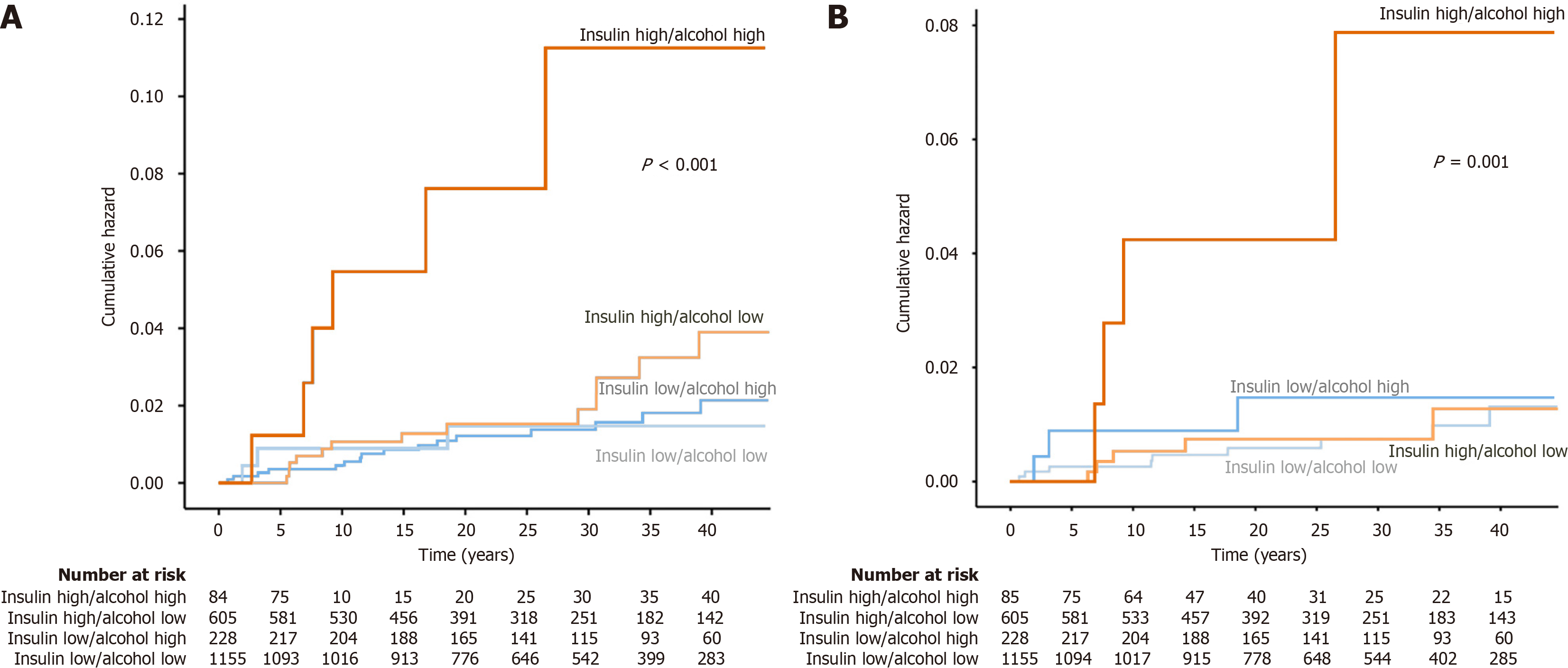

Kaplan-Meier analysis showed a significantly higher risk of developing liver disease in participants with high intake of alcohol combined with insulin levels in the upper tertile compared with all other combinations (Figure 3A). Univariable Cox regression showed a HR of 5.4 (95%CI: 2.3-13.0, P < 0.001) for this group. After adjustment for age, sex, and smoking, the HR was 4.3 (95%CI: 1.8-10.5, P = 0.001).

Twenty-three diagnoses of liver cirrhosis were made. Excluding two cases before baseline, there were ten cases of liver cirrhosis in women and 11 cases in men corresponding to incidence rates of 23.8 (95%CI: 12.1-42.5) and 78.5 (95%CI: 41.4-136.4) per 100000 person-years, respectively. Specific diagnoses for liver disease and cirrhosis are available as Supplemental Table 3.

In univariable Cox regression analysis, higher baseline levels of alcohol consumption (HR = 1.26 per 10 g ethanol, 95%CI: 1.12-1.43, P < 0.001), waist circumference (HR = 1.05, 95%CI: 1.01-1.09, P = 0.025) and current smoking (HR = 3.96, 95%CI: 1.59-9.86, P = 0.003) were associated with higher risk for development of liver cirrhosis.

The highest risk of liver cirrhosis was seen in participants with high insulin levels and high alcohol consumption (Figure 3B). The HR for this group was 6.7 (95%CI: 2.2-20.0, P < 0,001) compared with other participants. After adjustment for sex, age, smoking and waist circumference, the HR was 4.8 (95%CI: 1.6-14.6, P = 0.005).

To examine whether insulin was correlated with death, such that participants may have died before developing elevated LFT or liver disease, a Cox proportional hazards analysis was performed, modelling death as the outcome with sex, age, smoking, LTPA, alcohol and coffee consumption, and insulin as exposure variables. Age and smoking were strongly correlated with death, whereas insulin was not (HR = 1.00, 95%CI: 0.99-1.00, P = 0.39).

Sensitivity analyses were performed for both LFT, and liver disease/cirrhosis endpoints. After excluding participants with elevated LFT or liver disease at baseline, there were 174 events and 41 events of elevated LFT during follow-up in women and men, respectively. The results for LFT remained statistically significant in the multivariable Cox regression and the corresponding HR are shown in Table 3.

The association of high insulin with incident cases of liver disease remained unchanged after excluding 4 participants with liver disease within 3 years of baseline in both univariable and multivariable analyses (HR = 4.5, 95%CI: 1.7-11.8 for participants with a combination of insulin within the upper tertile and alcohol intake above metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis cut-offs).

For cirrhosis, after excluding 3 out of 21 cases of liver cirrhosis diagnosed within 3 years of baseline, alcohol (HR = 1.24, 95%CI: 1.07-1.44, P = 0.004), smoking (HR = 3.10, 95%CI: 1.20-8.05, P = 0.020) and baseline insulin levels (HR = 1.03, 95%CI: 1.00-1.06, P = 0.039) were associated with incident liver cirrhosis, whereas waist circumference was not. The adjusted HR for liver cirrhosis in the group with high insulin levels and high alcohol intake was 6.5 (95%CI: 2.1-20.0, P = 0.001).

The main finding of this study is the association of higher insulin levels with elevated LFT. This association was seen in men in the cross-sectional analysis, and in both sexes in the longitudinal analyses with a follow-up of 13 years in men and 24 years in women. This study also shows that participants with higher insulin levels at baseline examination had a higher risk of being diagnosed with liver disease. This risk was further increased in participants who had both high insulin levels and a high alcohol consumption. This group had a significantly higher risk of developing both liver disease and cirrhosis. In addition to alcohol, other modifiable risk factors for elevated LFT were sedentary level of physical activity and central obesity (expressed as waist circumference), while higher coffee consumption was associated with a lower risk of elevated LFT.

Type 2 diabetes has been shown to be more common in patients with liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma and is a risk factor for the development of liver cirrhosis in patients with MASLD[23]. Type 2 diabetes is also linked to liver disease and liver cancer[24-26] and is preceded by insulin resistance[27]. Evidence of hyperinsulinemia has been reported in studies on patients with MASLD[7,28,29]. This study provides further evidence that hyperinsulinemia is a risk factor for elevated LFTs and advanced liver disease. Hyperinsulinemia may be present for many years before there is overt evidence of elevated LFTs or liver disease.

Similar findings have been reported in other population-based studies in Finland and the United States. Åberg et al[30] showed that the Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) was correlated with the development of significant liver disease. In the NHANES III cohort, insulin resistance was a risk factor for liver-related mortality in patients with hepatitis C, alcoholic liver disease and MASLD[31].

The increased risk of liver disease and liver cirrhosis in subjects with high insulin levels and high alcohol consumption illustrates the interplay between metabolic risk factors and the hepatotoxic effect of alcohol, which was also seen in the Finnish study[30]. Outside clinical trials, it is difficult to quantify the exact amount of alcohol consumed and the cut-off for MASLD of > 21 standard drinks in men and > 14 standard drinks in women[32] is arbitrary. In patients with MASLD, even small to moderate amounts of alcohol have been shown to be associated with increased fibrosis[33,34] although a Swedish study found an inverse association[35].

Fatty liver disease can occur with other liver diseases and may exacerbate them. This has been described in alcoholic liver disease[36,37], viral hepatitis[38,39], autoimmune hepatitis[40,41], hemochromatosis[42] and primary biliary cholangitis[43]. Most of these diseases progress slowly over time and some patients will never reach the stage of cirrhosis[44,45]. Insulin resistance may not only be a major cause of MASLD but may also be considered a metabolic risk factor for more severe liver disease, independent of the underlying diagnosis. The combination of chronic liver disease and metabolic risk factors may lead to accelerated disease progression and earlier diagnosis.

Based on the knowledge that metabolic risk factors can coexist and aggravate other liver diseases, an international panel of experts proposed the term Metabolic (Dysfunction) Associated Fatty Liver Disease to accurately describe the impact of metabolic risk factors on the development of liver disease[46]. This concept has been further developed into a new nomenclature of steatotic liver disease that emphasizes the etiologic impact of insulin resistance for metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease–MASLD[47]. Although the importance of insulin resistance was recognized, neither insulin nor HOMA-IR were included in the diagnostic criteria for MASLD.

The strengths of the present study are that it is derived from representative samples from the general population with long follow-up, both in the sampling of LFT and in the detection of diagnoses of liver disease from registries with high coverage and validity[21,22]. The ability to analyze insulin in serum samples from 1968 in women provides a unique opportunity to study the long-term effects of hyperinsulinemia. Unfortunately, we were not able to analyze insulin levels in men at their earliest examination in 1963. Instead, they were sampled in 1980 at the ages of 57 years or 67 years, respectively, which was older than the age of the women. This still results in decades of follow-up, but it was much shorter than in women. Because of the difference in both age and follow-up time, incidence rates between the sexes should be interpreted with caution. The long time between baseline and an elevated LFT or clinical outcome could also introduce bias, as participants could change their lifestyle. However, this seems to play a minor role as there were significant correlations in variables such as BMI, coffee and alcohol consumption between baseline and follow-up.

Other limitations include incomplete sampling of baseline LFT in women when only one in four women had LFT results. In men, only aminotransaminases were obtained at the last follow-up in 1993. Sampling of LFT was also done at different time intervals since baseline in men and women. It was not possible to diagnose hepatitis C during the main study period. Hepatitis C is associated with insulin resistance[48] and it cannot be excluded that undiagnosed hepatitis C patients could influence the results. With regard to the clinical diagnosis of liver disease and liver cirrhosis, the number of events is rather small, which could lead to an overestimation of the HR[49].

In conclusion, this long-term population-based study provides evidence that high insulin levels are a risk factor for development of elevated liver enzymes and clinically manifest liver disease. There was a synergistic effect of alcohol and insulin on the risk of liver disease and cirrhosis. The study results support the concept of metabolic dysfunction associated liver disease.

Sadly, Per-Olof Hansson passed away on March 17, 2024. Since this work was initiated with him, the other authors decided to submit the paper with him as a co-author in tribute to a dear colleague and friend.

| 1. | Blachier M, Leleu H, Peck-Radosavljevic M, Valla DC, Roudot-Thoraval F. The burden of liver disease in Europe: a review of available epidemiological data. J Hepatol. 2013;58:593-608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 879] [Cited by in RCA: 908] [Article Influence: 75.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64:73-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5322] [Cited by in RCA: 7522] [Article Influence: 835.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Siow W, van der Poorten D, George J. Epidemiological Trends in NASH as a Cause for Liver Transplant. Curr Hepatology Rep. 2016;15:67-74. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Targher G, Bertolini L, Padovani R, Rodella S, Tessari R, Zenari L, Day C, Arcaro G. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and its association with cardiovascular disease among type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1212-1218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 702] [Cited by in RCA: 700] [Article Influence: 38.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Dai W, Ye L, Liu A, Wen SW, Deng J, Wu X, Lai Z. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e8179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 24.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cortez-Pinto H, Camilo ME, Baptista A, De Oliveira AG, De Moura MC. Non-alcoholic fatty liver: another feature of the metabolic syndrome? Clin Nutr. 1999;18:353-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Marchesini G, Brizi M, Bianchi G, Tomassetti S, Bugianesi E, Lenzi M, McCullough AJ, Natale S, Forlani G, Melchionda N. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a feature of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes. 2001;50:1844-1850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1725] [Cited by in RCA: 1745] [Article Influence: 72.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bugianesi E, McCullough AJ, Marchesini G. Insulin resistance: a metabolic pathway to chronic liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;42:987-1000. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 574] [Cited by in RCA: 615] [Article Influence: 30.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Thomas DD, Corkey BE, Istfan NW, Apovian CM. Hyperinsulinemia: An Early Indicator of Metabolic Dysfunction. J Endocr Soc. 2019;3:1727-1747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 24.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Vozarova B, Stefan N, Lindsay RS, Saremi A, Pratley RE, Bogardus C, Tataranni PA. High alanine aminotransferase is associated with decreased hepatic insulin sensitivity and predicts the development of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51:1889-1895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 485] [Cited by in RCA: 503] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bonnet F, Ducluzeau PH, Gastaldelli A, Laville M, Anderwald CH, Konrad T, Mari A, Balkau B; RISC Study Group. Liver enzymes are associated with hepatic insulin resistance, insulin secretion, and glucagon concentration in healthy men and women. Diabetes. 2011;60:1660-1667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Schult A, Eriksson H, Wallerstedt S, Kaczynski J. Overweight and hypertriglyceridemia are risk factors for liver cirrhosis in middle-aged Swedish men. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:738-744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Schult A, Mehlig K, Björkelund C, Wallerstedt S, Kaczynski J. Waist-to-hip ratio but not body mass index predicts liver cirrhosis in women. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:212-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tibblin G, Aurell E, Hjortzberg-Nordlund H, Paulin S, Risholm L, Sanne H, Wilhelmsen L, Werkoe L. A General Health-Examination of A Random Sample of 50-Year-Old Men in Goeteborg. Acta Med Scand. 1965;177:739-749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Rosengren A, Eriksson H, Hansson PO, Svärdsudd K, Wilhelmsen L, Johansson S, Welin C, Welin L. Obesity and trends in cardiovascular risk factors over 40 years in Swedish men aged 50. J Intern Med. 2009;266:268-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Saltin B, Grimby G. Physiological analysis of middle-aged and old former athletes. Comparison with still active athletes of the same ages. Circulation. 1968;38:1104-1115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 730] [Cited by in RCA: 761] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lapidus L, Bengtsson C, Bergfors E, Björkelund C, Spak F, Lissner L. Alcohol intake among women and its relationship to diabetes incidence and all-cause mortality: the 32-year follow-up of a population study of women in Gothenburg, Sweden. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2230-2235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD); European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016;64:1388-1402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2290] [Cited by in RCA: 3174] [Article Influence: 352.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 19. | Hales CN, Randle PJ. Immunoassay of insulin with insulin antibody preciptate. Lancet. 1963;1:200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ludvigsson JF, Otterblad-Olausson P, Pettersson BU, Ekbom A. The Swedish personal identity number: possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2009;24:659-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1814] [Cited by in RCA: 1824] [Article Influence: 114.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, Feychting M, Kim JL, Reuterwall C, Heurgren M, Olausson PO. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3938] [Cited by in RCA: 4013] [Article Influence: 286.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Brooke HL, Talbäck M, Hörnblad J, Johansson LA, Ludvigsson JF, Druid H, Feychting M, Ljung R. The Swedish cause of death register. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32:765-773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 516] [Cited by in RCA: 964] [Article Influence: 120.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Alexander M, Loomis AK, van der Lei J, Duarte-Salles T, Prieto-Alhambra D, Ansell D, Pasqua A, Lapi F, Rijnbeek P, Mosseveld M, Waterworth DM, Kendrick S, Sattar N, Alazawi W. Risks and clinical predictors of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma diagnoses in adults with diagnosed NAFLD: real-world study of 18 million patients in four European cohorts. BMC Med. 2019;17:95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 36.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Björkström K, Franzén S, Eliasson B, Miftaraj M, Gudbjörnsdottir S, Trolle-Lagerros Y, Svensson AM, Hagström H. Risk Factors for Severe Liver Disease in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:2769-2775.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | El-Serag HB, Tran T, Everhart JE. Diabetes increases the risk of chronic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:460-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 873] [Cited by in RCA: 892] [Article Influence: 42.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Porepa L, Ray JG, Sanchez-Romeu P, Booth GL. Newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for serious liver disease. CMAJ. 2010;182:E526-E531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lyssenko V, Almgren P, Anevski D, Perfekt R, Lahti K, Nissén M, Isomaa B, Forsen B, Homström N, Saloranta C, Taskinen MR, Groop L, Tuomi T; Botnia study group. Predictors of and longitudinal changes in insulin sensitivity and secretion preceding onset of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54:166-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Sanyal AJ, Campbell-Sargent C, Mirshahi F, Rizzo WB, Contos MJ, Sterling RK, Luketic VA, Shiffman ML, Clore JN. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: association of insulin resistance and mitochondrial abnormalities. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1183-1192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1458] [Cited by in RCA: 1510] [Article Influence: 62.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Chitturi S, Abeygunasekera S, Farrell GC, Holmes-Walker J, Hui JM, Fung C, Karim R, Lin R, Samarasinghe D, Liddle C, Weltman M, George J. NASH and insulin resistance: Insulin hypersecretion and specific association with the insulin resistance syndrome. Hepatology. 2002;35:373-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 807] [Cited by in RCA: 822] [Article Influence: 35.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Åberg F, Helenius-Hietala J, Puukka P, Färkkilä M, Jula A. Interaction between alcohol consumption and metabolic syndrome in predicting severe liver disease in the general population. Hepatology. 2018;67:2141-2149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 28.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Stepanova M, Rafiq N, Younossi ZM. Components of metabolic syndrome are independent predictors of mortality in patients with chronic liver disease: a population-based study. Gut. 2010;59:1410-1415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, Charlton M, Cusi K, Rinella M, Harrison SA, Brunt EM, Sanyal AJ. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;67:328-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3544] [Cited by in RCA: 4936] [Article Influence: 705.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 33. | Blomdahl J, Nasr P, Ekstedt M, Kechagias S. Moderate alcohol consumption is associated with advanced fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and shows a synergistic effect with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism. 2021;115:154439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Chang Y, Cho YK, Kim Y, Sung E, Ahn J, Jung HS, Yun KE, Shin H, Ryu S. Nonheavy Drinking and Worsening of Noninvasive Fibrosis Markers in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Cohort Study. Hepatology. 2019;69:64-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Hagström H, Nasr P, Ekstedt M, Kechagias S, Önnerhag K, Nilsson E, Rorsman F, Sheikhi R, Marschall HU, Hultcrantz R, Stål P. Low to moderate lifetime alcohol consumption is associated with less advanced stages of fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:159-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Naveau S, Giraud V, Borotto E, Aubert A, Capron F, Chaput JC. Excess weight risk factor for alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 1997;25:108-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 449] [Cited by in RCA: 436] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Raynard B, Balian A, Fallik D, Capron F, Bedossa P, Chaput JC, Naveau S. Risk factors of fibrosis in alcohol-induced liver disease. Hepatology. 2002;35:635-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 254] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Bondini S, Kallman J, Wheeler A, Prakash S, Gramlich T, Jondle DM, Younossi ZM. Impact of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease on chronic hepatitis B. Liver Int. 2007;27:607-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Moucari R, Asselah T, Cazals-Hatem D, Voitot H, Boyer N, Ripault MP, Sobesky R, Martinot-Peignoux M, Maylin S, Nicolas-Chanoine MH, Paradis V, Vidaud M, Valla D, Bedossa P, Marcellin P. Insulin resistance in chronic hepatitis C: association with genotypes 1 and 4, serum HCV RNA level, and liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:416-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 375] [Cited by in RCA: 377] [Article Influence: 22.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 40. | Takahashi A, Arinaga-Hino T, Ohira H, Abe K, Torimura T, Zeniya M, Abe M, Yoshizawa K, Takaki A, Suzuki Y, Kang JH, Nakamoto N, Fujisawa T, Tanaka A, Takikawa H; Japan AIH Study Group (JAIHSG). Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. JGH Open. 2018;2:54-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | De Luca-Johnson J, Wangensteen KJ, Hanson J, Krawitt E, Wilcox R. Natural History of Patients Presenting with Autoimmune Hepatitis and Coincident Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:2710-2720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Powell EE, Ali A, Clouston AD, Dixon JL, Lincoln DJ, Purdie DM, Fletcher LM, Powell LW, Jonsson JR. Steatosis is a cofactor in liver injury in hemochromatosis. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1937-1943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Seike T, Komura T, Shimizu Y, Omura H, Kumai T, Kagaya T, Ohta H, Kawashima A, Harada K, Kaneko S, Unoura M. A Young Man with Non-alcoholic Steatohepatitis and Serum Anti-mitochondrial Antibody Positivity. Intern Med. 2018;57:3093-3097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Lackner C, Tiniakos D. Fibrosis and alcohol-related liver disease. J Hepatol. 2019;70:294-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 33.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Poynard T, Ratziu V, Charlotte F, Goodman Z, McHutchison J, Albrecht J. Rates and risk factors of liver fibrosis progression in patients with chronic hepatitis c. J Hepatol. 2001;34:730-739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 513] [Cited by in RCA: 497] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Eslam M, Sanyal AJ, George J; International Consensus Panel. MAFLD: A Consensus-Driven Proposed Nomenclature for Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1999-2014.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2367] [Cited by in RCA: 2200] [Article Influence: 440.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 47. | Rinella ME, Lazarus JV, Ratziu V, Francque SM, Sanyal AJ, Kanwal F, Romero D, Abdelmalek MF, Anstee QM, Arab JP, Arrese M, Bataller R, Beuers U, Boursier J, Bugianesi E, Byrne CD, Castro Narro GE, Chowdhury A, Cortez-Pinto H, Cryer DR, Cusi K, El-Kassas M, Klein S, Eskridge W, Fan J, Gawrieh S, Guy CD, Harrison SA, Kim SU, Koot BG, Korenjak M, Kowdley KV, Lacaille F, Loomba R, Mitchell-Thain R, Morgan TR, Powell EE, Roden M, Romero-Gómez M, Silva M, Singh SP, Sookoian SC, Spearman CW, Tiniakos D, Valenti L, Vos MB, Wong VW, Xanthakos S, Yilmaz Y, Younossi Z, Hobbs A, Villota-Rivas M, Newsome PN; NAFLD Nomenclature consensus group. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Hepatology. 2023;78:1966-1986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1212] [Cited by in RCA: 1298] [Article Influence: 649.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Eslam M, Khattab MA, Harrison SA. Insulin resistance and hepatitis C: an evolving story. Gut. 2011;60:1139-1151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Steyerberg EW, Eijkemans MJ, Habbema JD. Stepwise selection in small data sets: a simulation study of bias in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:935-942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 324] [Cited by in RCA: 321] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |