Published online Dec 21, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i47.8367

Peer-review started: October 26, 2017

First decision: November 21, 2017

Revised: November 30, 2017

Accepted: December 4, 2017

Article in press: December 4, 2017

Published online: December 21, 2017

Processing time: 55 Days and 17.9 Hours

To examine the association between white opaque substance (WOS) and histologically verified lipid droplets in colorectal epithelial neoplasms.

We reviewed colonoscopy records at our institution from 2014 to 2016 and identified cases of endoscopically or surgically resected colorectal epithelial neoplasms observed by magnifying narrow-band imaging (M-NBI) colonoscopy. Immunohistochemistry was used to stain tumors with a monoclonal antibody specific to adipophilin as a marker of lipids. The expression and distribution of adipophilin were compared between WOS-positive and WOS-negative lesions and among tumors classified by histologic type and depth of invasion.

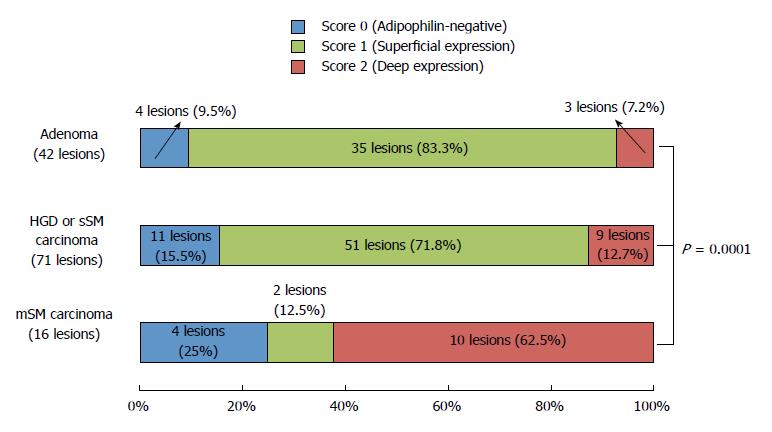

Under M-NBI colonoscopy, 81 lesions were positive for WOS and 48 lesions were negative for WOS. The rate of adipophilin expression was significantly higher in WOS-positive lesions (95.1%) than in WOS-negative lesions (68.7%) (P = 0.0001). The incidence of deep adipophilin expression was higher in WOS-positive lesions (24.7%) than in WOS-negative lesions (4.2%) (P = 0.001). The incidence of deep expression was predominant among cancers with massive submucosal invasion (62.5%) compared to adenoma (7.2%) and high-grade dysplasia or cancers with slight submucosal invasion (12.7%) (P = 0.0001).

The distribution of lipid droplets may be closely associated with the visibility of WOS under M-NBI colonoscopy, and with histologic grade and depth of tumor invasion.

Core tip: We investigated the association between the distribution of the lipid droplets and endoscopically-verified white opaque substance (WOS) in colorectal neoplasms. The incidence of deep adipophilin expression was higher in WOS-positive lesions than in WOS-negative lesions. The incidence of deep expression was predominant among cancers with massive submucosal invasion compared to adenoma and high-grade dysplasia or cancers with slight submucosal invasion. We thus concluded that the distribution of lipid droplets may be closely associated with the visibility of WOS, and also with histologic grade and depth of tumor invasion.

- Citation: Kawasaki K, Eizuka M, Nakamura S, Endo M, Yanai S, Akasaka R, Toya Y, Fujita Y, Uesugi N, Ishida K, Sugai T, Matsumoto T. Association between white opaque substance under magnifying colonoscopy and lipid droplets in colorectal epithelial neoplasms. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(47): 8367-8375

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i47/8367.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i47.8367

White opaque substance (WOS) under magnifying narrow-band imaging (M-NBI) endoscopy has been reported to be a novel endoscopic finding in gastric neoplasms[1]. Yao et al[1] reported that WOS is valuable for distinguishing between gastric adenocarcinoma and gastric adenoma. WOS has also been observed in other gastrointestinal tract neoplasms, such as esophageal adenocarcinoma originating from esophageal glands, duodenal neoplasms, and colorectal neoplasms[2-4]. We recently reported that irregular distribution of WOS in colorectal neoplasms may be a sign of massively invading submucosal colorectal cancer[5].

In gastric and duodenal neoplasms, WOS has been shown to represent an accumulation of lipid droplets[3,6]. Lipid staining for gastric and duodenal epithelial neoplasms has demonstrated that most gastric neoplasms with WOS are positive for oil red O staining[6], and the distribution of Sudan IV-positive lipid droplets corresponds approximately with that of WOS in duodenal neoplasms[3]. To date, however, only a single study investigated the histopathological features of WOS in colorectal epithelial neoplasms[7]. In that study, Imamura et al[7] reported that WOS in colorectal epithelial neoplasms was composed of lipid droplets. However, the association between the distribution of the lipid droplets and endoscopically-verified WOS in colorectal neoplasms remains unclear.

We conducted a single-center, retrospective analysis to examine the association between lipid droplets and WOS in colorectal epithelial neoplasms. We also compared the distribution of lipid droplets among tumors classified by histologic type and depth of invasion.

The present investigation was based on retrospective data collection. We reviewed the endoscopy database at our institution from 2014 to 2016, and identified all patients with a diagnosis of colorectal epithelial neoplasm removed by endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) or laparoscopic surgery. Among those tumors, we excluded colorectal epithelial neoplasms, which cannot be observed by M-NBI colonoscopy. We also excluded cancers invading the proper muscular layer. The protocol of this retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Iwate Medical University.

Demographics of study subjects were extracted via chart review. Evaluated characteristics included age, sex, colonoscopic findings (size, location, and morphology), and M-NBI colonoscopic findings. The location of each lesion was classified as right side (cecum to transverse colon) or left side (descending colon to rectum). The gross morphology was defined as protruding type or flat-elevated type, based on the Paris classification[8].

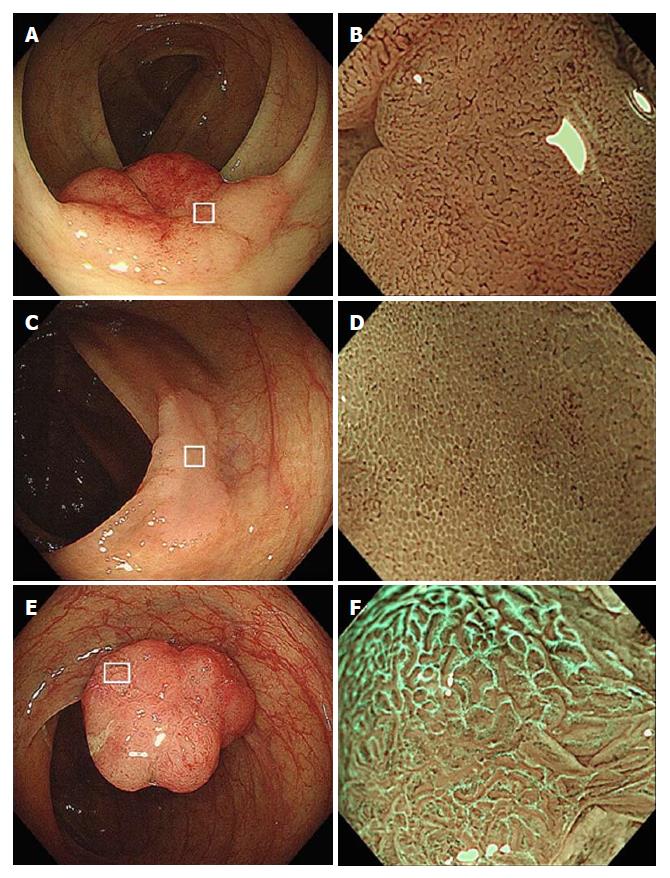

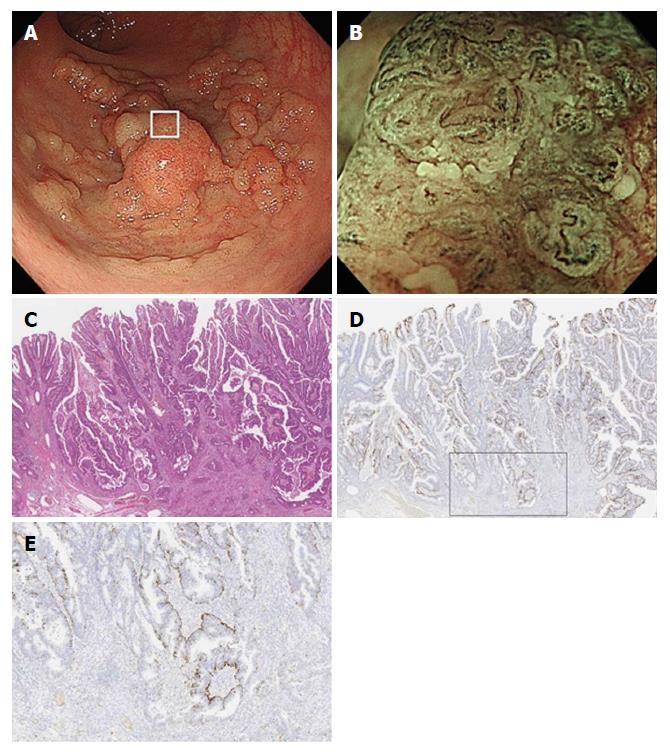

As has been reported previously[5], we defined WOS as a whitish area on M-NBI colonoscopy that obscures the microvascular pattern within the colorectal epithelial neoplasm (Figure 1). When M-NBI colonoscopy revealed an area of WOS, the lesion was considered WOS-positive. WOS was further classified into regular and irregular WOS based on the classifications proposed by Yao et al[1] and by our group[5]. Regular WOS was defined as WOS observed in a well-organized and symmetrical distribution with a regular reticular, maze-like, or speckled pattern. In contrast, irregular WOS was defined as WOS that appeared in a disorganized and asymmetrical distribution with an irregular reticular or speckled pattern (Figure 1).

Histological diagnosis was based on the WHO classification proposed in 2000[9]. The grade of dysplastic change was classified as adenoma, high-grade dysplasia (HGD), or carcinoma. Carcinoma was defined as neoplastic glands that had invaded the submucosal layer. Carcinomas were further classified as those with massive submucosal invasion (mSM) and those with slight submucosal invasion (sSM). mSM carcinoma was defined as having a vertical invasion depth > 1000 μm, while sSM carcinoma was defined as having an invasion depth < 1000 μm[8,10].

All sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in a graded ethanol series. Slides were autoclaved in citrate buffer (pH 9.0) at 97 °C for 20 min by PT Link (Dako EnVision System, Denmark). To clarify lipid accumulation, a primary antibody against adipophilin (pre-dilution, AP125; Fitzgerald Industries International, Concord, MA, United States) was used. Immunostaining for adipophilin was performed using an autoimmunostaining system (Dako EnVision System, Denmark).

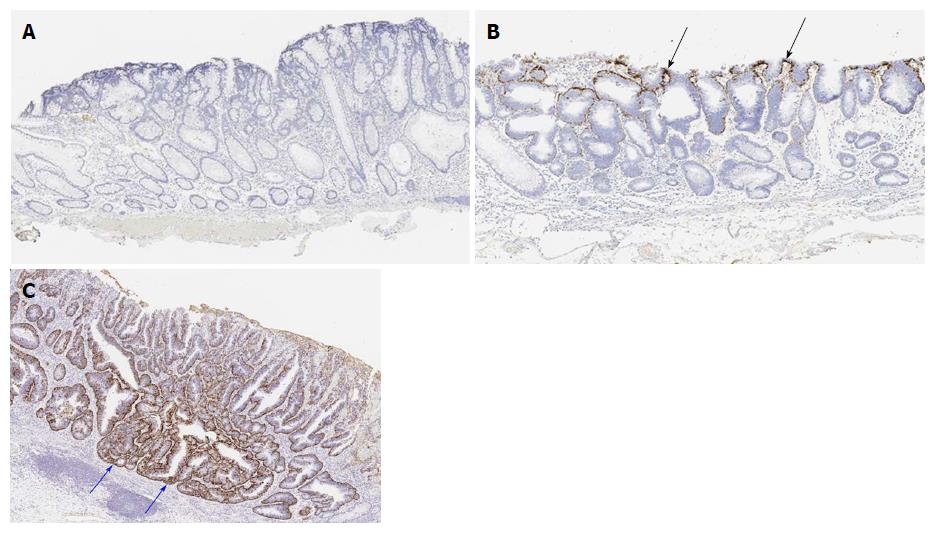

The intensity of adipophilin expression was tabulated as negative, weak, moderate and strong. When the intensity of adipophilin-positive neoplastic cells was moderate or strong, the lesion was regarded as being adipophilin-positive. Depth of adipophilin expression was scored as 0 (negative), 1 (superficial expression), and 2 (deep expression) (Figure 2). When the depth of proper mucosal layer was divided into five equal layers, score 1 (superficial expression) was defined as having a vertical adipophilin expression no more than one-fifth, while score 2 (deep expression) was defined as having a vertical adipophilin expression more than one-fifth.

Scores were determined by two pathologists (ME and TS). When any difference in scoring occurred, the pathologists discussed the case until a consensus was obtained.

Parametric data are expressed as mean ± SD. Nonparametric data are expressed as numbers and percentages. Comparisons between any two or among any three groups were performed by chi-squared test, the Tukey honestly significant difference test, or Student’s t test where appropriate. P < 0.05 were considered significant. All statistical computations were performed with JMP version 11 (Statistical Discovery Program, Cary, NC, United States).

A total of 129 lesions in 120 patients were included in this study. Overall, 81 lesions in 74 patients were regarded as WOS-positive and 48 lesions in 46 patients as WOS-negative (Figure 1). Neither age at the time of diagnosis of colorectal epithelial neoplasms (70.6 ± 8.6 years in patients with WOS-positive lesions and 68.6 ± 9.1 years in the remaining patients) nor gender (55.4% male in patients with WOS-positive lesions and 45.8% in the remaining patients) differed between patient groups.

Comparisons of endoscopic and histological characteristics between WOS-positive and WOS-negative lesions are shown in Table 1. No differences in tumor size, tumor location, gross morphology, or histologic type were observed between the two groups.

| WOS-positive | WOS-negative | P value | ||

| (81 lesions) | (48 lesions) | |||

| Size (mm), mean ± SD | 32.8 ± 16.4 | 34.7 ± 18.3 | 0.51 | |

| Location | Right side of the colon | 51 (63.0) | 22 (45.8) | 0.07 |

| Left side of the colon | 30 (37.0) | 26 (54.2) | ||

| Morphology | Protruded type | 20 (24.7) | 14 (29.2) | 0.68 |

| Flat-elevated type | 61 (75.3) | 34 (70.8) | ||

| Histologic type | Adenoma | 22 (27.2) | 20 (41.7) | 0.12 |

| HGD or carcinoma | 59 (72.8) | 28 (58.3) |

Table 2 compares adipophilin positivity rates between WOS-positive and WOS-negative lesions. Overall, 77 of the 81 WOS-positive lesions (95.1%) were adipophilin-positive, while 33 of the 48 WOS-negative lesions (68.7%) were adipophilin-positive (Figures 1 and 2). The adipophilin positivity rate was significantly higher in WOS-positive lesions than in WOS-negative lesions (P = 0.0001).

| WOS-positive | WOS-negative | P value | ||

| (81 lesions) | (48 lesions) | |||

| Adipophilin | Positive | 77 (95.1) | 33 (68.7) | 0.0001 |

| Negative | 4 (4.9) | 15 (31.3) |

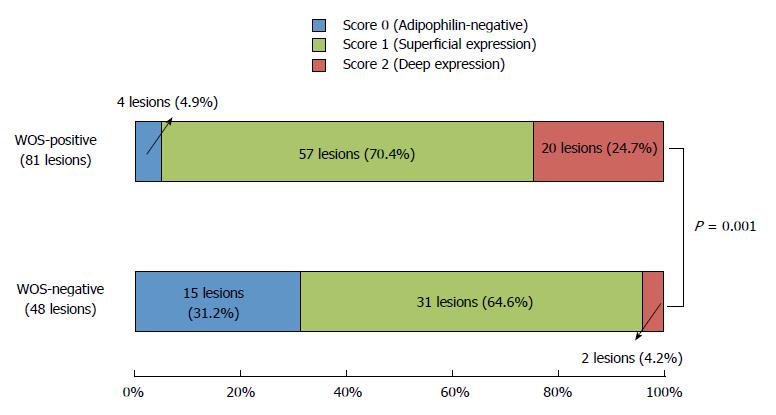

Figure 3 compares the distribution of adipophilin expression between WOS-positive and WOS-negative lesions. The score for depth of adipophilin expression was significantly different between the two groups (P = 0.001), with a predominance of score 2 (deep expression) (Figure 2) in WOS-positive lesions (24.7%) compared to 4.2% in WOS-negative lesions.

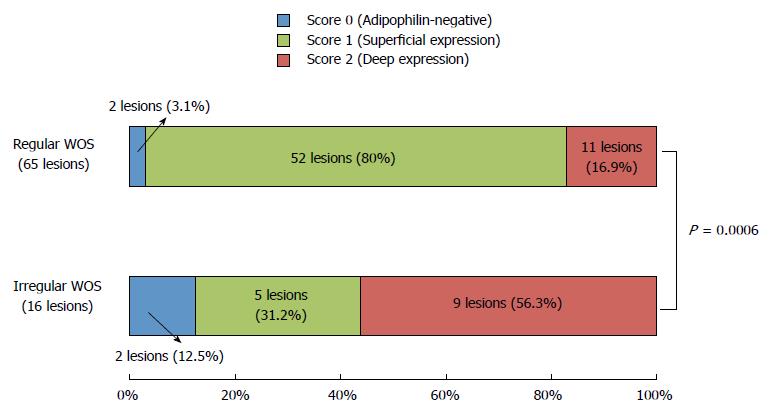

WOS-positive lesions were further classified as having regular WOS (65 lesions) or irregular WOS (16 lesions) (Figure 1). Figure 4 compares the distribution of adipophilin between lesions with regular vs. irregular WOS. Deep adipophilin expression was more frequent in lesions with irregular WOS (56.3%) than in those with regular WOS (16.9%) (P = 0.0006) (Figure 2).

Histologically, the 129 lesions included 42 adenomas, 63 HGDs, 8 sSM carcinomas, and 16 mSM carcinomas. Figure 5 compares adipophilin expression between adenomas, HGD/sSM carcinomas, and mSM carcinomas. A score of 2 (deep expression) was more frequent in mSM carcinomas (62.5%) than in adenomas (7.2%) and HGDs/sSM carcinomas (12.7%) (P = 0.0001). Figure 6 shows a case of mSM carcinoma with irregular WOS.

In this study, we confirmed that colorectal neoplasms with positive WOS under M-NBI colonoscopy had more profound accumulation of adipophilin compared to those without WOS. We also confirmed that the depth of adipophilin accumulation within tumors was associated with the visibility and morphology of WOS. Furthermore, we showed that the depth of adipophilin accumulation was associated with histologic grade of dysplasia and depth of invasion in colorectal tumors.

WOS under M-NBI endoscopy appears as a white deposit that obscures the subepithelial microvascular pattern in gastric neoplasms, duodenal neoplasms, esophageal adenocarcinoma originating from esophageal glands, and colorectal neoplasms, as well as in gastric and colorectal hyperplasic polyps[1-5,11,12]. WOS has been histopathologically and immunohistochemically verified to be a consequence of intramucosal accumulation of lipid droplets. Gastric neoplasms with WOS have been shown to be positive for oil red O staining and adipophilin[6,13-15], and duodenal neoplasms with WOS have been reported to be positive for Sudan IV[3].

Only a single clinicopathologic study that evaluated WOS in colorectal neoplasms has been published[7]. In that study, Imamura et al[7] reported that 19 (47.5%) of 40 colorectal lesions with WOS were positive for oil red O staining, while only 5 (5%) of 40 colorectal lesions without WOS were positive. Moreover, the investigators reported that 40 (100%) of 40 colorectal lesions with WOS were positive for adipophilin, while 25 (62.5%) of 40 colorectal lesions without WOS were positive. In the present study, we observed similar trends in the association between WOS and adipophilin expression. Thus, it seems possible that as in gastric and duodenal neoplasms, WOS in colorectal tumors represents accumulation of lipid droplets in the neoplastic epithelium.

The incidence of lipid droplets in gastric neoplasms without WOS has been reported in the literature to be extremely low. Yao et al[6] reported that only 1 (4.3%) of 23 WOS-negative lesions was positive for oil red O. Ueo et al[13] also reported a similar trend: only 2 (7.4%) of 27 WOS-negative lesions were positive for adipophilin. With regards to colorectal neoplasms, only 2 (5%) of 40 WOS-negative lesions were positive for oil red O[7]. As observed in our present investigation, however, Imamura et al[7] reported a much higher rate (62.5%) of adipophilin-positive expression in biopsy specimens obtained from WOS-negative colorectal tumors. The study investigators[7] also observed a significantly lower density of adipophilin in WOS-negative lesions compare to WOS-positive lesions. These observations strongly suggest that WOS under M-NBI is less sensitive for the detection of lipid droplets in colorectal tumors than in gastric tumors.

In the present study, we also investigated the histological distribution of lipid droplets in colorectal lesions that were completely resected by endoscopy or surgery. Thus, we were able to assess the depth of adipophilin expression in the samples. We found that deep expression of adipophilin was more frequent in WOS-positive lesions than in WOS-negative lesions. Thus, it seems possible that WOS under M-NBI may be representative of the total volume of lipid droplets in colorectal tumors.

The present results also showed that deep adipophilin expression was more frequent in mSM carcinomas than in adenomas or HGDs/sSM carcinomas. Yao et al[6] reported that 10 (36.5%) of 26 gastric neoplasms were positive for oil O red staining within surface epithelial cells, while 16 (61.5%) of 26 gastric neoplasms were positive for oil O red both in surface epithelial cells and in the subepithelial region. Ueo et al[13] reported that surface plus cryptal accumulation of adipophilin was frequent in gastric cancers, while surface accumulation was observed in most gastric adenomas. It thus seems possible that the intraepithelial localization of lipid droplets in gastric tumors differs according to the histological grade of dysplasia. However, the association between lipid droplet accumulation and tumor invasion depth has not been examined in gastric epithelial tumors to date. In contrast, our results suggested that the depth of adipophilin expression may be correlated with the depth of invasion, rather than the histologic grade, in colorectal tumors.

In our previous analysis, the incidence of mSM carcinoma was significantly and conspicuously higher among lesions with irregular WOS (82.4%) than among those with regular WOS (1.4%)[5]. In the present study, lesions with irregular WOS had deeper adipophilin expression than those with regular WOS. It thus seems possible that irregular WOS may be a consequence of massive lipid droplet accumulation in colorectal tumors. This speculation appears to partially explain the high rate of submucosal invasion in lesions with irregular WOS. Lipid droplets may be directly or indirectly associated with the malignant potential of colorectal neoplasms.

The present study has several limitations. First, since we included only lesions removed by ESD or surgery and did not include small lesions, it remains unclear whether the present observations are applicable to smaller colorectal lesions. Second, the present results were based on a retrospective analysis in a single center. A need exists for prospective analysis of a greater number of colorectal epithelial neoplasms to determine the association between lipid droplets and WOS under NBI, and also the clinical significance of WOS for the diagnosis and treatment of colorectal tumors.

In conclusion, the present immunohistochemical study showed that WOS observed in colorectal tumors under M-NBI colonoscopy represents lipid droplets. In addition, the distribution of lipid droplets may be closely associated with the visibility of WOS under M-NBI colonoscopy, and also with histologic grade and depth of tumor invasion. Further prospective studies are warranted to establish the clinical significance of WOS for the diagnosis and treatment of colorectal epithelial tumors and the association between lipid droplets and WOS under NBI.

White opaque substance (WOS) under magnifying narrow-band imaging (M-NBI) endoscopy is a novel endoscopic finding for the diagnosis of gastrointestinal tract neoplasms. In previous studies, WOS has been shown to contain lipid droplets. However, the association between the distribution of the lipid droplets and endoscopically verified WOS in colorectal neoplasms remains unclear.

The elucidation of WOS or lipid droplets in colorectal epithelial tumors will help the diagnosis and treatment of colorectal epithelial tumors.

To examine the association between WOS and histologically verified lipid droplets in colorectal epithelial neoplasms.

We conducted this retrospective study involving 129 lesions of endoscopically or surgically resected colorectal epithelial neoplasms observed by M-NBI colonoscopy. Immunohistochemistry was used to stain tumors with a monoclonal antibody specific to adipophilin as a marker of lipids. The expression and distribution of adipophilin were compared between WOS-positive and WOS-negative lesions and among tumors classified by histologic type and depth of invasion.

81 lesions were positive for WOS and 48 lesions were negative for WOS. The rate of adipophilin expression was significantly higher in WOS-positive lesions (95.1%) than in WOS-negative lesions (68.7%) (P = 0.0001). The incidence of deep adipophilin expression was higher in WOS-positive lesions (24.7%) than in WOS-negative lesions (4.2%) (P = 0.001). The incidence of deep expression was predominant among cancers with massive submucosal invasion (62.5%) compared to adenoma (7.2%) and high-grade dysplasia or cancers with slight submucosal invasion (12.7%) (P = 0.0001).

The distribution of lipid droplets may be closely associated with the visibility of WOS under M-NBI colonoscopy, and with histologic grade and depth of tumor invasion.

Our study showed that WOS under M-NBI colonoscopy appears to represent lipid droplets and the distribution of lipid droplets may be closely associated with the visibility of WOS with histologic grade and depth of tumor invasion. The accumulation of lipid droplets may directly or indirectly represent the malignant potential of colon cancer cells. Further prospective studies are warranted to establish the clinical significance of WOS for the diagnosis and treatment of colorectal epithelial tumors and the association between lipid droplets and WOS under NBI.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Alberti LR, Arya V S- Editor: Chen K L- Editor: A E- Editor: Huang Y

| 1. | Yao K, Iwashita A, Tanabe H, Nishimata N, Nagahama T, Maki S, Takaki Y, Hirai F, Hisabe T, Nishimura T. White opaque substance within superficial elevated gastric neoplasia as visualized by magnification endoscopy with narrow-band imaging: a new optical sign for differentiating between adenoma and carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:574-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Yoshii S, Kato M, Honma K, Fujinaga T, Tsujii Y, Maekawa A, Inoue T, Hayashi Y, Akasaka T, Shinzaki S. Esophageal adenocarcinoma with white opaque substance observed by magnifying endoscopy with narrow band imaging. Dig Endosc. 2015;27:392-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yoshimura N, Goda K, Tajiri H, Ikegami M, Nakayoshi T, Kaise M. Endoscopic features of nonampullary duodenal tumors with narrow-band imaging. Hepatogastroenterology. 2010;57:462-467. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Hisabe T, Yao K, Imamura K, Ishihara H, Hirai F, Matsui T, Iwashita A. White opaque substance visualized using magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging in colorectal epithelial neoplasms. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:2544-2549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kawasaki K, Kurahara K, Yanai S, Oshiro Y, Eizuka M, Uesugi N, Ishida K, Nakamura S, Fuchigami T, Sugai T. Significance of a white opaque substance under magnifying narrow-band imaging colonoscopy for the diagnosis of colorectal epithelial neoplasms. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:1097-1104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yao K, Iwashita A, Nambu M, Tanabe H, Nagahama T, Maki S, Ishikawa H, Matsui T, Enjoji M. Nature of white opaque substance in gastric epithelial neoplasia as visualized by magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging. Dig Endosc. 2012;24:419-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Imamura K, Yao K, Hisabe T, Nambu M, Ohtsu K, Ueo T, Yano S, Ishihara H, Nagahama T, Kanemitsu T. The nature of the white opaque substance within colorectal neoplastic epithelium as visualized by magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging. Endosc Int Open. 2016;4:E1151-E1157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Participants in the Paris Workshop. The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: esophagus, stomach, and colon. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:S3-S43. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1117] [Cited by in RCA: 1327] [Article Influence: 60.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 9. | Hamilton SR, Adaltonen LA, editors . World Health Organization classification of tumors: pathology and genetics of tumors of the digestive system. Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer 2000; 103-119. |

| 10. | Kitajima K, Fujimori T, Fujii S, Takeda J, Ohkura Y, Kawamata H, Kumamoto T, Ishiguro S, Kato Y, Shimoda T. Correlations between lymph node metastasis and depth of submucosal invasion in submucosal invasive colorectal carcinoma: a Japanese collaborative study. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:534-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 468] [Cited by in RCA: 486] [Article Influence: 23.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ueyama H, Matsumoto K, Nagahara A, Gushima R, Hayashi T, Yao T, Watanabe S. A white opaque substance-positive gastric hyperplastic polyp with dysplasia. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:4262-4266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hisabe T, Yao K, Imamura K, Ishihara H, Yamasaki K, Yasaka T, Matsui T, Iwashita A. Novel Endoscopic Findings as Visualized by Magnifying Endoscopy with Narrow-Band Imaging: White Opaque Substance Is Present in Colorectal Hyperplastic Polyps. Digestion. 2016;93:127-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ueo T, Yonemasu H, Yada N, Yano S, Ishida T, Urabe M, Takahashi K, Nagamatsu H, Narita R, Yao K. White opaque substance represents an intracytoplasmic accumulation of lipid droplets: immunohistochemical and immunoelectron microscopic investigation of 26 cases. Dig Endosc. 2013;25:147-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Enjoji M, Kohjima M, Ohtsu K, Matsunaga K, Murata Y, Nakamuta M, Imamura K, Tanabe H, Iwashita A, Nagahama T. Intracellular mechanisms underlying lipid accumulation (white opaque substance) in gastric epithelial neoplasms: A pilot study of expression profiles of lipid-metabolism-associated genes. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:776-781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ueo T, Yonemasu H, Yao K, Ishida T, Togo K, Yanai Y, Fukuda M, Motomura M, Narita R, Murakami K. Histologic differentiation and mucin phenotype in white opaque substance-positive gastric neoplasias. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3:E597-E604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |