Published online Jul 28, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i28.5216

Peer-review started: March 7, 2017

First decision: April 25, 2017

Revised: June 11, 2017

Accepted: June 19, 2017

Article in press: June 19, 2017

Published online: July 28, 2017

Processing time: 143 Days and 10.2 Hours

To evaluate the psychometric properties of a newly developed questionnaire, known as the gastroesophageal reflux and dyspepsia therapeutic efficacy and satisfaction test (GERD-TEST), in patients with GERD.

Japanese patients with predominant GERD symptoms recruited according to the Montreal definition were treated for 4 wk using a standard dose of proton pump inhibitor (PPI). The GERD-TEST and the Medical Outcome Study Short Form-8 Health Survey (SF-8) were administered at baseline and after 4 wk of treatment. The GERD-TEST contains three domains: the severity of GERD and functional dyspepsia (FD) symptoms (5 items), the level of dissatisfaction with daily life (DS) (4 items), and the therapeutic efficacy as assessed by the patients and medication compliance (4 items).

A total of 290 patients were eligible at baseline; 198 of these patients completed 4 wk of PPI therapy. The internal consistency reliability as evaluated using the Cronbach’s α values for the GERD, FD and DS subscales ranged from 0.75 to 0.82. The scores for the GERD, FD and DS items/subscales were significantly correlated with the physical and mental component summary scores of the SF-8. After 4 wk of PPI treatment, the scores for the GERD items/subscales were greatly reduced, ranging in value from 1.51 to 1.87 and with a large effect size (P < 0.0001, Cohen’s d; 1.29-1.63). Statistically significant differences in the changes in the scores for the GERD items/subscales were observed between treatment responders and non-responders (P < 0.0001).

The GERD-TEST has a good reliability, a good convergent and concurrent validity, and is responsive to the effects of treatment. The GERD-TEST is a simple, easy to understand, and multifaceted PRO instrument applicable to both clinical trials and the primary care of GERD patients.

Core tip: A patient-reported outcome (PRO) can be a clinically relevant outcome measure of disease impact and treatment response in both clinical trials and primary care. The practical use and dissemination of PRO as a diagnostic and evaluation tool is anticipated; however, most PROs are lengthy and complicated. Therefore, we developed a simple, easy-to-understand and multifaceted PRO instrument, the gastroesophageal reflux and dyspepsia therapeutic efficacy and satisfaction test (GERD-TEST). The psychometric characteristics of the GERD-TEST were excellent, demonstrating good validity and reliability. The GERD-TEST enabled a multifaceted evaluation not only of the severity of symptoms, but also of the impact of the symptoms on daily life, the therapeutic response as assessed by the patient. The GERD-TEST is expected to be a useful diagnostic/treatment tool for both clinical research and in daily clinical practice settings.

- Citation: Nakada K, Matsuhashi N, Iwakiri K, Oshio A, Joh T, Higuchi K, Haruma K. Development and validation of a simple and multifaceted instrument, GERD-TEST, for the clinical evaluation of gastroesophageal reflux and dyspeptic symptoms. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(28): 5216-5228

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i28/5216.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i28.5216

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is defined as a condition that develops when the reflux of stomach contents causes troublesome symptoms and/or complications, according to the Montreal definition[1]. GERD is a chronic condition that interferes with various aspects of daily life such as eating, sleeping, daily activities and mood. GERD is one of the most common disorders treated in primary care, and its overall prevalence appears to have increased in Japan recent years[2-4].

GERD, even without any complications, poses a problem in that the symptoms of the disease interfere with various aspects of daily living, thereby lowering the quality of life (QOL) of the patient[5,6]. It is important, therefore, to diagnose patients appropriately and to treat patients efficiently.

Reportedly, concurrent functional dyspepsia (FD) is frequently encountered in patients with GERD[7-12]. FD is also generally recognized as having an untoward effect on a patient’s daily living, with a consequent reduction in QOL[13-15]. Thus, the possible presence of concurrent manifestations of FD should be considered even in patients seeking medical advice for GERD symptoms, and if FD symptoms are present, they should be treated appropriately and at the same time.

The importance of patient-reported outcome (PRO) in evaluating medical care has been stressed in recent years[16-20]. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidance[16] recommends the use of an appropriate PRO measure with proven reliability and validity for the treatment of disorders in which the treatment goal is to ameliorate symptoms. The application of PRO not only in clinical trials, but also in daily clinical practice settings would enable greater objectivity in the diagnosis and evaluation of therapeutic responses in GERD cases and the provision of effective and efficient treatment. However, an optimal PRO for GERD patients does not presently exist. Most of the previously developed PROs for GERD were too long or were too complicated to use in routine clinical care, and most were not well validated for the diagnosis of GERD, the evaluation of symptom-induced burden, the impact on daily life, or the therapeutic response. The lack of a simple, easy to understand instrument for GERD patients encouraged the development of the presently reported gastroesophageal reflux and dyspepsia therapeutic efficacy and satisfaction test (GERD-TEST).

The concepts behind the newly developed questionnaire, known as the GERD-TEST, were as follows: (1) Simplicity (i.e., a minimum number of items), (2) easy to understand; (3) applicability to the diagnosis of GERD and the evaluation of symptom-induced burden, impact on daily life, and therapeutic response after treatment; (4) the ability to detect simultaneous FD; and (5) applicability to both clinical trials and primary care.

The aim of the present study was to assess the reliability and validity of the GERD-TEST in a population of patients who had been diagnosed as having GERD according to the Montreal definition.

This was a multicenter, prospective, observational study conducted at 29 institutions in Japan, in which one or more investigators per institution was a member of the GERD Society, a Japanese collaborative research group consisting of experts in clinical practice of GERD. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (sixth revision, 2008), after approval by the ethics committee of each institution or the central ethics committee of Nishi Clinic, Osaka, Japan. The study was registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network Center Clinical Trials Registry in Japan (reference number UMIN000006614).

Outpatients with symptomatic GERD who received proton pump inhibitor (PPI) treatment in routine clinical care were recruited for this study. After endoscopic examination, patients were treated with a PPI at a dosage approved in Japan before the start of this study (April 2011), i.e., omeprazole 20 mg once daily, lansoprazole 30 mg once daily, or rabeprazole 10 or 20 mg once daily.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) moderate or severe heartburn or acid regurgitation at least once a week or mild heartburn or acid regurgitation at least twice a week during the 2 wk prior to the start of the study (the Montreal definition); (2) at least 20 years of age; and (3) provision of written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria were (1) comorbidity or history of disease that could potentially affect the study results [for example, Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), esophageal stricture, eosinophilic esophagitis, achalasia, malabsorption, or cerebrovascular disease]; (2) concurrent symptoms of concern such as vomiting, peptic ulcer except those in the scarred stage, and severe hepatic or renal or cardiac diseases, mental disorder, uncontrolled metabolic diseases, neurological diseases, collagen diseases, or other diseases; (3) confirmed or suspected malignancy; (4) history of gastrointestinal tract resection or vagotomy; (5) history of hypersensitivity to PPIs or their excipients; (6) Helicobacter pylori eradication within 6 mo before enrollment; (7) pregnancy, possible pregnancy, or breastfeeding; (8) ingestion of PPI or histamine type 2 (H2)-receptor antagonist within 1 wk of enrollment; and (9) patients otherwise deemed to be ineligible by the attending physician.

Prohibited concomitant drugs were those that might affect the study results (PPIs other than the study drugs, H2-receptor antagonists, prokinetic agents, gastric mucosal protective agents, and anticholinergic drugs), and drugs that might interact with the study drugs.

Severity of reflux esophagitis was assessed according to the modified Los Angeles classification system[21,22]. Patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics were recorded before beginning PPI therapy (0w) with a series of questionnaires. GERD and dyspeptic symptoms and QOL were assessed using the GERD-TEST[23] and the acute (1-wk-recall) version of a health-related QOL survey (SF-8)[24], respectively, at 0 wk, 2 wk, and 4 wk after PPI treatment. Psychiatric bias was assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale[25] at 0 wk and 4 wk. All questionnaires were completed and mailed to the data center by the study participants.

Patient characteristics were recorded using a questionnaire that included sex, age, height, weight, and lifestyle factors (regularity of daily life, consumption of caffeine-containing beverages or high-fat meals, smoking status, and alcohol consumption).

The GERD-TEST is a patient-reported questionnaire composed of 13 items for investigating GERD and dyspepsia symptoms, impact to the patient’s daily life, and patient’s impression of the therapy. Questions (Q) 1 to Q5 of the GERD-TEST assess the severity of upper abdominal symptoms; Q6-Q9 assess the impact of symptoms on daily life, including eating, sleeping, daily activity, and mood; Q10-Q12 evaluate the therapeutic response to the PPIs; Q13 asks compliance with the medication; Q1-Q11 and Q13 use a Likert scale; Q12 uses an numeric rating scale (NRS) (Table 1).

| Q1. Have you been bothered by heartburn during the past week? (By heartburn we mean a burning pain or discomfort behind the breastbone in your chest) | ||||||||

| Q2. Have you been bothered by acid regurgitation during the past week? (By acid regurgitation we mean regurgitation or flow of sour or bitter fluid into your mouth) | ||||||||

| Q3. Have you been bothered by epigastric pain or burning during the past week? (Epigastric pain includes any type of pain of the stomach) | ||||||||

| Q4. Have you been bothered by postprandial fullness during the past week? (Postprandial fullness refers to discomfort or a sensation of heaviness caused by the food you consume remaining in the stomach) | ||||||||

| Q5. Have you been bothered by early satiation during the past week? (Early satiation refers to the inability to finish a normally sized meal) | ||||||||

| Response scale for Q1-5: | ||||||||

| 1 = no discomfort at all, 2 = slight discomfort, 3 = mild discomfort, 4 = moderate discomfort, 5 = moderately severe discomfort, 6 = severe discomfort, 7 = very severe discomfort. | ||||||||

| Q6. During the past week, how often have you felt dissatisfaction because you were unable to eat meals as you intended due to chest and stomach symptoms? (Not being able to eat as you intended refers to the inability to eat the sufficient amount of food you want to eat at an uninhibited, natural pace) | ||||||||

| Q7. During the past week, how often have you felt dissatisfaction due to impaired sleep caused by chest and stomach symptoms? | ||||||||

| Q8. During the past week, how often have you felt dissatisfaction due to impairment of your work, housework, or other daily activities caused by chest and stomach symptoms? | ||||||||

| Q9. During the past week, how often have you felt dissatisfaction because you were in a bad mood due to chest and stomach symptoms? | ||||||||

| Response scale for Q.6-9: | ||||||||

| 1 = not at all, 2 = slightly, 3 = moderately, 4 = quite a lot, 5 = extremely. | ||||||||

| Q10. During the past week, how often have you wanted another drug in addition to the drug your doctor prescribed because of intense symptoms of heartburn and acid regurgitation? | ||||||||

| 1 = not at all, 2 = on 1 d, 3 = on 2 to 3 d, 4 = on 4 to 5 d, 5 = always. | ||||||||

| Q11. During the past week, how have you felt about symptoms of heartburn and acid regurgitation as compared with the symptom severity before current treatment? | ||||||||

| 1 = extremely improved, 2 = improved, 3 = slightly improved, 4 = not changed, 5 = aggravated. | ||||||||

| Q12. If 10 corresponds to your symptoms before current treatment and 0 is "symptom-free", what number corresponds to symptoms of heartburn and acid regurgitation during the past week? Please circle the applicable score below: | ||||||||

| 0 | ………….. 1 ………….. 2 ………..... 3 ………..... 4….…….... 5 ………..... 6 ….……... 7 …..……... 8 ….…….... 9 ………..... | 10 | ||||||

| | | | | |||||||

| Symptom-free | Symptoms before current treatment | |||||||

| Q13. What proportion of the proton pump inhibitor prescribed to you did you take as instructed? | ||||||||

| 1 = took drug as instructed, 2 = generally took drug as instructed (took at least three-quarters of the drug prescribed), 3 = sometimes forgot (took at least half but less than three-quarters of the drug prescribed, 4 = took little (took less than half of the drug prescribed), 5 = did not take any. | ||||||||

The SF-8 is a generic questionnaire used to investigate health status and is composed of a physical component summary (PCS) and a mental component summary (MCS)[20]. These scores are normalized to the general population, with higher scores indicating better physical and mental QOL, with a normative score of 50 and a SD of 10.

The GERD-SS was defined as the mean of scores for heartburn (Q1) and regurgitation (Q2). The FD-SS was defined as the mean of scores for epigastric pain/burning (Q3) and postprandial distress symptoms (the mean of scores for postprandial fullness [Q4] and early satiation [Q5]). The dissatisfaction with daily life (DS)-SS defined as the mean of scores for dissatisfaction with eating (Q6), sleeping (Q7), daily activities (Q8) and mood (Q9).

To assess the therapeutic response to PPI in patients with GERD, three outcome measures were used, as follows: (1) Residual symptom rate of GERD-SS, which was calculated as 100 (%) × (GERD-SS score at 4 wk-1)/(GERD-SS score 0 wk-1), and therefore was 100% when GERD-SS score at 4 wk equaled that at 0 wk, and was 0% when the patient had no symptoms (a score of 1) at 4 wk. A higher residual symptom rate thus reflects a poorer response; (2) Patient’s impression of therapy, which was the score for Q11 of GERD-TEST (i.e., the score of impression of improvement in GERD symptoms as compared with the severity before taking current prescription, 1 for extremely improved, 2 for improved, 3 for slightly improved, 4 for not changed and 5 for aggravated); and (3) Relative GERD symptom intensity quantified using an 11-point (i.e., 0 for no symptoms to 10 for symptoms before taking current prescription).

The responder definition for each outcome measure was defined as follows, (1) residual symptom rate ≤ 50%; (2) patient’s impression of improved or better; and (3) NRS ≤ 5, respectively.

Data analysis was undertaken using JMP10.0.2 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States). All statistical tests were performed using a two-sided test with a significance level of 0.05.

Cronbach’s α is a coefficient of internal consistency that is commonly used as an estimate of the reliability of a psychometric test. Consequently, the Cronbach’s α values were calculated from pairwise correlations between items to verify the internal consistency of the items in each subscale.

Correlations between the scores for symptoms or dissatisfaction with daily life (DS) items/subscales and the PCS or MCS of the SF-8, as well as correlations between the scores for symptoms and DS items/subscales, were calculated in terms of the Pearson correlation coefficient (r), where values of r ≥ 0.100, ≥ 0.300, and ≥ 0.500 were considered to be small, medium, and large effects, respectively[26].

The symptom and dissatisfaction scores obtained before and after therapy were compared using a paired t-test, and the symptom and DS scores at baseline and after 4 wk of PPI therapy and the changes in the scores before and after 4 wk of PPI therapy between responders and non-responders according to three different responder definitions were compared using unpaired t-tests. The effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were then calculated, where Cohen’s d values of ≥ 0.20, ≥ 0.50, and ≥ 0.80 were considered to be small, medium, and large effects, respectively[26].

To identify the types of symptoms that showed a response when therapeutic efficacy was assessed by the patients, multiple regression analyses were performed using the changes in scores for both the GERD-SS and the FD-SS before and after 4 wk of PPI therapy as explanatory variables; the outcome measures of the therapeutic response at 4 wk (i.e., the patient’s impression of the therapy [Q11] and the relative symptom intensity according to a NRS [Q12]) were used as objective variables. Interpretation of effect sizes were ≥ 0.1 small, ≥ 0.3 medium, and ≥ 0.5 large in standardization coefficient of regression [β]; ≥ 0.02 small, ≥ 0.13 medium, and ≥ 0.26 large in coefficient of determination [R2].

A total of 290 patients were eligible at baseline; 178 (61%) were men, the mean age was 57.5 ± 13.9 years, and the mean body mass index (BMI) was 24.0 ± 3.9 kg/m2. A diagnosis of erosive reflux disease (ERD) was made in 183 (63%) of the cases, while a diagnosis of nonerosive reflux disease (NERD) was made in 107 (37%) cases based on the results of an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Of these patients, 198 completed 4 wk of PPI therapy and were eligible for inclusion in the analysis; 126 (64%) of these patients were men, the mean age was 57.9 ± 13.1 years, and the mean BMI was 24.2 ± 4.1 kg/m2. A diagnosis of ERD was made in 134 (68%) of the cases, and a diagnosis of NERD was made in 64 (32%) of the cases based on the results of an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (Table 2).

| At baseline (n = 290) | Accomplished 4W | |

| PPI Tx (n = 198) | ||

| Age (mean ± SD, yr) | 57.5 ± 13.9 | 57.9 ± 13.1 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 178 (61) | 126 (64) |

| Female | 112 (39) | 72 (36) |

| BMI (mean ± SD, kg/m2) | 24.0 ± 3.9 | 24.2 ± 4.1 |

| Endoscopic findings | ||

| NERD | 107 (37) | 64 (32) |

| Grade N | 62 (21) | 38 (19) |

| Grade M | 45 (16) | 26 (13) |

| ERD | 183 (63) | 134 (68) |

| Grade A | 94 (32) | 66 (33) |

| Grade B | 60 (21) | 47 (24) |

| Grade C | 21 (7) | 14 (7) |

| Grade D | 8 (3) | 7 (4) |

Of the 290 symptomatic GERD patients who were recruited according to the Montreal definition, 246 (85%) were identified as GERD patients based on the results of the GERD-TEST (i.e., the score for Q1 [heartburn] and/or Q2 [regurgitation] was ≥ 3).

The internal consistency of the items in each of the three subscales (GERD-SS, FD-SS and DS-SS) was acceptable, as shown by the Cronbach’s α values (which ranged from 0.75 to 0.82) (Table 3).

| Subscales | Cronbach's α |

| GERD-SS | 0.78 |

| Heartburn | |

| Acid regurgitation | |

| FD-SS | 0.75 |

| Epigastric pain/burning | |

| Postprandial fullness | |

| Early satiation | |

| Dissatisfaction for daily life SS | 0.82 |

| Dissatisfaction for eating | |

| Dissatisfaction for sleeping | |

| Dissatisfaction for daily activity | |

| Dissatisfaction for the mood |

The Pearson’s r for comparisons of the GERD-TEST with the SF-8 were used to assess convergent validity. There was a significant negative correlation between each of the GERD-TEST items/subscales and the PCS or MCS of the SF-8 [Pearson’s r = (-0.19)-(-0.55)] (Table 4). In addition, a significant positive correlation was seen between each of the symptom items/subscales and the DS items/subscale of the GERD-TEST (Pearson’s r = 0.32-0.72) (Table 4).

| PCS | MCS | Q6. Eating | Q7. Sleeping | Q8. Daily activity | Q9. Mood | |||||||||

| r | P value | r | P value | r | P value | r | P value | r | P value | r | P value | r | P value | |

| Q1. Heartburn | -0.267 | < 0.0001 | -0.236 | < 0.0001 | 0.331 | < 0.0001 | 0.420 | < 0.0001 | 0.479 | < 0.0001 | 0.560 | < 0.0001 | 0.558 | < 0.0001 |

| Q2. Acid regurgitation | -0.214 | 0.0003 | -0.193 | 0.0012 | 0.379 | < 0.0001 | 0.406 | < 0.0001 | 0.458 | < 0.0001 | 0.498 | < 0.0001 | 0.553 | < 0.0001 |

| GERD-SS | -0.266 | < 0.0001 | -0.238 | < 0.0001 | 0.393 | < 0.0001 | 0.457 | < 0.0001 | 0.517 | < 0.0001 | 0.585 | < 0.0001 | 0.614 | < 0.0001 |

| Q3. Epigastric pain or burning | -0.311 | < 0.0001 | -0.327 | < 0.0001 | 0.452 | < 0.0001 | 0.445 | < 0.0001 | 0.483 | < 0.0001 | 0.520 | < 0.0001 | 0.595 | < 0.0001 |

| Q4. Postprandial fullness | -0.173 | 0.0037 | -0.402 | < 0.0001 | 0.554 | < 0.0001 | 0.317 | < 0.0001 | 0.448 | < 0.0001 | 0.510 | < 0.0001 | 0.568 | < 0.0001 |

| Q5. Early satiation | -0.222 | 0.0002 | -0.354 | < 0.0001 | 0.716 | < 0.0001 | 0.336 | < 0.0001 | 0.440 | < 0.0001 | 0.463 | < 0.0001 | 0.606 | < 0.0001 |

| FD-SS | -0.305 | < 0.0001 | -0.424 | < 0.0001 | 0.658 | < 0.0001 | 0.468 | < 0.0001 | 0.560 | < 0.0001 | 0.611 | < 0.0001 | 0.716 | < 0.0001 |

| Q6. Eating | -0.307 | < 0.0001 | -0.378 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||||

| Q7. Sleeping | -0.216 | 0.0003 | -0.407 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||||

| Q8. Daily activity | -0.356 | < 0.0001 | -0.494 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||||

| Q9. Mood | -0.307 | < 0.0001 | -0.496 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||||

| Dissatisfaction for daily life-SS | -0.370 | < 0.0001 | -0.553 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||||

| Effect size | Small | Medium | Large | |||||||||||

| r | 0.1 ≤ | 0.3 ≤ | 0.5 ≤ | |||||||||||

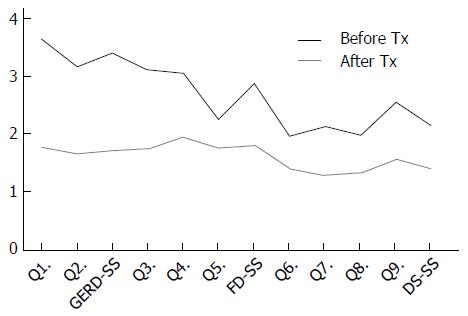

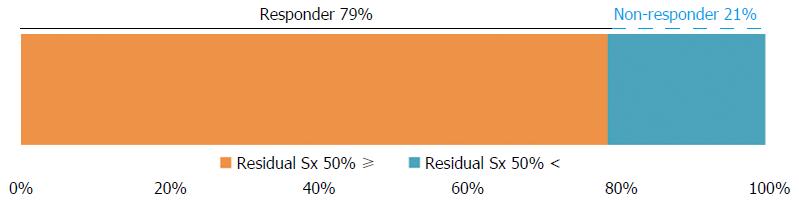

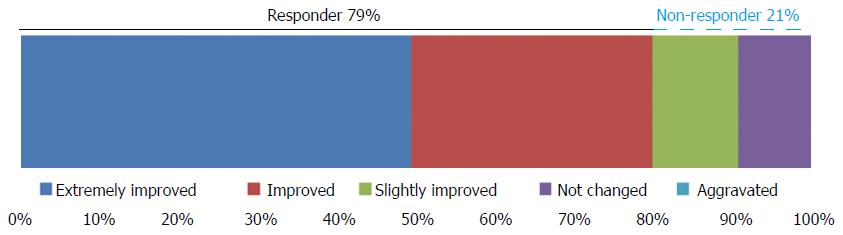

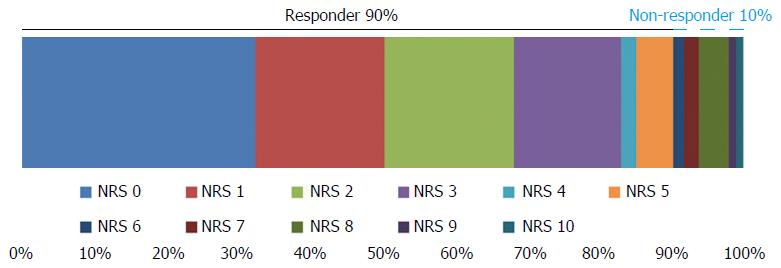

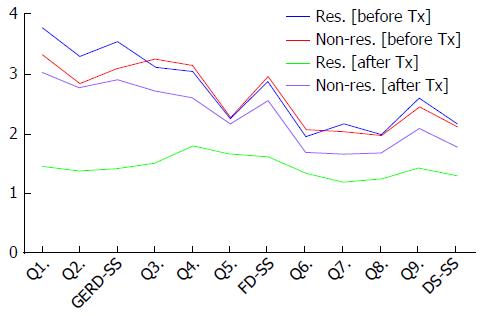

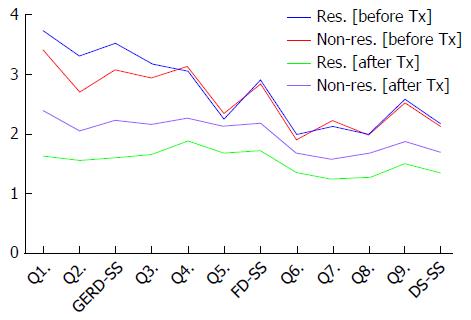

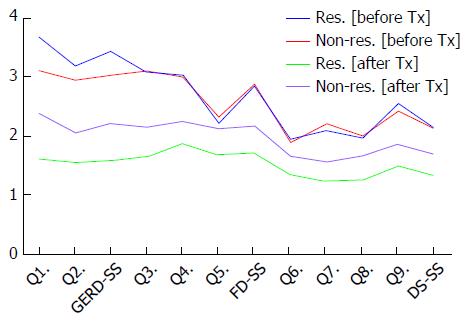

The GERD-TEST scores at baseline and after 4 wk of PPI therapy are shown in Figure 1. The distances between the lines on the graph show the score changes after treatment. The rates of responders after 4 wk of PPI therapy according to three different responder definitions were 79% for the “residual symptom rate ≤ 50%” definition (Figure 2), 79% for the “patient’s impression of improved or better” definition (Figure 3), and 90% for the “NRS ≤ 5” definition (Figure 4), respectively.

The GERD-TEST scores at baseline and after 4 wk of PPI therapy in responders and non-responders according to three different responder definitions are shown in Figures 5-7. The distance between the graph lines for baseline and after 4 wk of PPI therapy for both responders and non-responders show the score changes arising from treatment in the respective groups. The distances between the graph lines (i.e., the score changes arising from treatment) were greater for responders than for non-responders as well as for GERD symptom items/subscales, compared with those for FD symptoms or DS (Figures 1, 5-7 and Tables 5-8).

| Before Tx | After 4 wk PPI Tx | Cohen's d | P value | |||

| mean | SD | mean | SD | |||

| Q1. Heartburn | 3.64 | 1.31 | 1.77 | 0.97 | 1.63 | < 0.0001 |

| Q2. Acid regurgitation | 3.17 | 1.37 | 1.66 | 0.95 | 1.29 | < 0.0001 |

| GERD-SS | 3.40 | 1.20 | 1.71 | 0.91 | 1.59 | < 0.0001 |

| Q3. Epigastric pain or burning | 3.11 | 1.40 | 1.75 | 1.02 | 1.11 | < 0.0001 |

| Q4. Postprandial fullness | 3.05 | 1.34 | 1.95 | 1.06 | 0.91 | < 0.0001 |

| Q5. Early satiation | 2.25 | 1.34 | 1.76 | 0.91 | 0.42 | < 0.0001 |

| FD-SS | 2.88 | 1.13 | 1.80 | 0.85 | 1.08 | < 0.0001 |

| Q6. Eating | 1.97 | 1.07 | 1.41 | 0.74 | 0.61 | < 0.0001 |

| Q7. Sleeping | 2.14 | 1.07 | 1.29 | 0.63 | 0.97 | < 0.0001 |

| Q8. Daily activity | 1.98 | 1.00 | 1.33 | 0.67 | 0.76 | < 0.0001 |

| Q9. Mood | 2.55 | 1.06 | 1.57 | 0.80 | 1.05 | < 0.0001 |

| Dissatisfaction for daily life-SS | 2.15 | 0.84 | 1.40 | 0.59 | 1.04 | < 0.0001 |

| Effect size | Small | Medium | Large | |||

| Cohen's d | 0.2 ≤ | 0.5 ≤ | 0.8 ≤ | |||

| r | 0.1 ≤ | 0.3 ≤ | 0.5 ≤ | |||

| Before Tx | After 4 wk PPI Tx | Δ (0W-4W) | ||||||||||||||||

| Responder definition by | Responder (n = 153) | Non-responder (n = 41) | Cohen's d | P value | Responder (n = 153) | Non-responder (n = 41) | Cohen's d | P value | Responder (n = 153) | Non-responder (n = 41) | Cohen's d | P value | ||||||

| Residual Sx 50% ≥ | mean | SD | mean | SD | mean | SD | mean | SD | mean | SD | mean | SD | ||||||

| Q1. Heartburn | 3.79 | 1.29 | 3.34 | 1.09 | 0.36 | 0.025 | 1.45 | 0.61 | 3.05 | 1.07 | 2.21 | < 0.0001 | -2.34 | 1.24 | -0.29 | 0.87 | 1.76 | < 0.0001 |

| Q2. Acid regurgitation | 3.31 | 1.32 | 2.85 | 1.37 | 0.34 | 0.060 | 1.37 | 0.57 | 2.78 | 1.24 | 1.86 | < 0.0001 | -1.93 | 1.25 | -0.07 | 1.17 | 1.51 | < 0.0001 |

| GERD-SS | 3.55 | 1.19 | 3.10 | 0.99 | 0.39 | 0.014 | 1.41 | 0.53 | 2.91 | 1.08 | 2.21 | < 0.0001 | -2.14 | 1.11 | -0.18 | 0.71 | 1.89 | < 0.0001 |

| Q3. Epigastric pain or burning | 3.12 | 1.42 | 3.27 | 1.18 | - | 0.509 | 1.51 | 0.84 | 2.73 | 1.10 | 1.36 | < 0.0001 | -1.61 | 1.41 | -0.54 | 1.03 | 0.81 | < 0.0001 |

| Q4. Postprandial fullness | 3.05 | 1.39 | 3.15 | 1.15 | - | 0.636 | 1.79 | 0.96 | 2.61 | 1.18 | 0.81 | < 0.0001 | -1.25 | 1.32 | -0.54 | 1.16 | 0.56 | 0.001 |

| Q5. Early satiation | 2.26 | 1.38 | 2.28 | 1.20 | - | 0.950 | 1.66 | 0.85 | 2.17 | 1.05 | 0.57 | 0.004 | -0.60 | 1.13 | -0.10 | 0.90 | 0.46 | 0.003 |

| FD-SS | 2.89 | 1.17 | 2.98 | 0.94 | - | 0.622 | 1.62 | 0.74 | 2.56 | 0.85 | 1.24 | < 0.0001 | -1.27 | 1.06 | -0.42 | 0.82 | 0.84 | < 0.0001 |

| Q6. Eating | 1.95 | 1.05 | 2.07 | 1.15 | - | 0.550 | 1.34 | 0.69 | 1.68 | 0.88 | 0.47 | 0.023 | -0.61 | 0.88 | -0.39 | 1.02 | 0.25 | 0.206 |

| Q7. Sleeping | 2.17 | 1.08 | 2.05 | 1.05 | - | 0.514 | 1.18 | 0.49 | 1.66 | 0.88 | 0.80 | 0.001 | -0.99 | 1.02 | -0.39 | 0.86 | 0.61 | 0.000 |

| Q8. Daily activity | 1.99 | 1.03 | 1.98 | 0.89 | - | 0.909 | 1.24 | 0.6 | 1.68 | 0.82 | 0.68 | 0.001 | -0.75 | 1.05 | -0.30 | 0.85 | 0.45 | 0.005 |

| Q9. Mood | 2.60 | 1.07 | 2.46 | 0.98 | - | 0.433 | 1.43 | 0.74 | 2.10 | 0.83 | 0.88 | < 0.0001 | -1.17 | 1.06 | -0.37 | 0.80 | 0.80 | < 0.0001 |

| Dissatisfaction for daily life-SS | 2.18 | 0.83 | 2.11 | 0.84 | - | 0.650 | 1.30 | 0.52 | 1.78 | 0.69 | 0.86 | < 0.0001 | -0.88 | 0.77 | -0.36 | 0.64 | 0.71 | < 0.0001 |

| Effect size | Small | Medium | Large | |||||||||||||||

| Cohen's d | 0.2 ≤ | 0.5 ≤ | 0.8 ≤ | |||||||||||||||

| Before Tx | After 4 wk PPI Tx | Δ (0W-4W) | ||||||||||||||||

| Responder definition by | Responder (n = 155) | Non-responder (n = 39) | Cohen's d | P value | Responder (n = 155) | Non-responder (n = 39) | Cohen's d | P value | Responder (n = 155) | Non-responder (n = 39) | Cohen's d | P value | ||||||

| Patients' impression improved ≤ | mean | SD | mean | SD | mean | SD | mean | SD | mean | SD | mean | SD | ||||||

| Q1. Heartburn | 3.72 | 1.31 | 3.41 | 1.25 | - | 0.169 | 1.62 | 0.88 | 2.38 | 1.14 | 0.82 | 0.000 | -2.10 | 1.42 | -1.03 | 1.25 | 0.78 | < 0.0001 |

| Q2. Acid regurgitation | 3.30 | 1.39 | 2.69 | 1.20 | 0.45 | 0.007 | 1.55 | 0.86 | 2.05 | 1.19 | 0.53 | 0.015 | -1.74 | 1.39 | -0.64 | 1.44 | 0.79 | < 0.0001 |

| GERD-SS | 3.51 | 1.23 | 3.05 | 1.01 | 0.39 | 0.017 | 1.59 | 0.83 | 2.22 | 1.08 | 0.71 | 0.001 | -1.92 | 1.29 | -0.83 | 1.10 | 0.87 | < 0.0001 |

| Q3. Epigastric pain or burning | 3.17 | 1.42 | 2.92 | 1.31 | - | 0.306 | 1.65 | 0.98 | 2.15 | 1.16 | 0.50 | 0.014 | -1.52 | 1.45 | -0.77 | 1.11 | 0.54 | 0.001 |

| Q4. Postprandial fullness | 3.04 | 1.39 | 3.13 | 1.22 | - | 0.691 | 1.88 | 1.07 | 2.26 | 1.04 | 0.36 | 0.045 | -1.16 | 1.33 | -0.87 | 1.28 | 0.22 | 0.212 |

| Q5. Early satiation | 2.23 | 1.38 | 2.33 | 1.24 | - | 0.662 | 1.67 | 0.88 | 2.13 | 0.98 | 0.51 | 0.008 | -0.56 | 1.13 | -0.21 | 0.95 | 0.33 | 0.044 |

| FD-SS | 2.90 | 1.17 | 2.83 | 0.97 | - | 0.697 | 1.71 | 0.84 | 2.17 | 0.83 | 0.55 | 0.002 | -1.19 | 1.10 | -0.65 | 0.86 | 0.51 | 0.001 |

| Q6. Eating | 1.99 | 1.08 | 1.90 | 1.07 | - | 0.641 | 1.35 | 0.70 | 1.67 | 0.87 | 0.43 | 0.036 | -0.64 | 0.89 | -0.23 | 0.90 | 0.46 | 0.013 |

| Q7. Sleeping | 2.12 | 1.08 | 2.21 | 1.08 | - | 0.646 | 1.23 | 0.58 | 1.56 | 0.79 | 0.55 | 0.013 | -0.89 | 1.04 | -0.64 | 0.93 | 0.25 | 0.146 |

| Q8. Daily activity | 1.98 | 1.01 | 1.97 | 0.97 | - | 0.968 | 1.26 | 0.63 | 1.67 | 0.74 | 0.63 | 0.002 | -0.72 | 1.02 | -0.32 | 0.96 | 0.41 | 0.021 |

| Q9. Mood | 2.57 | 1.07 | 2.51 | 1.05 | - | 0.771 | 1.50 | 0.8 | 1.87 | 0.77 | 0.47 | 0.007 | -1.07 | 1.06 | -0.64 | 1.01 | 0.41 | 0.020 |

| Dissatisfaction for daily life-SS | 2.16 | 0.84 | 2.12 | 0.84 | - | 0.768 | 1.33 | 0.57 | 1.69 | 0.63 | 0.62 | 0.001 | -0.83 | 0.77 | -0.45 | 0.68 | 0.50 | 0.003 |

| Effect size | Small | Medium | Large | |||||||||||||||

| Cohen's d | 0.2 ≤ | 0.5 ≤ | 0.8 ≤ | |||||||||||||||

| Before Tx | After 4 wk PPI Tx | Δ (0W-4W) | ||||||||||||||||

| Responder definition by | Responder (n = 176) | Non-responder (n = 19) | Cohen's d | P value | Responder (n = 176) | Non-responder (n = 19) | Cohen's d | P value | Responder (n = 176) | Non-responder (n = 19) | Cohen's d | P value | ||||||

| NRS 5 ≥ | mean | SD | mean | SD | mean | SD | mean | SD | mean | SD | mean | SD | ||||||

| Q1. Heartburn | 3.68 | 1.32 | 3.11 | 0.99 | 0.45 | 0.022 | 1.69 | 0.89 | 2.37 | 1.30 | 0.73 | 0.027 | -1.99 | 1.42 | -0.74 | 1.15 | 0.90 | < 0.0001 |

| Q2. Acid regurgitation | 3.19 | 1.37 | 2.95 | 1.22 | - | 0.423 | 1.56 | 0.84 | 2.32 | 1.16 | 0.87 | 0.006 | -1.63 | 1.39 | -0.63 | 0.83 | 0.75 | < 0.0001 |

| GERD-SS | 3.43 | 1.21 | 3.03 | 1.02 | - | 0.106 | 1.62 | 0.81 | 2.34 | 1.21 | 0.85 | 0.012 | -1.81 | 1.27 | -0.68 | 0.87 | 0.91 | < 0.0001 |

| Q3. Epigastric pain or burning | 3.08 | 1.38 | 3.11 | 1.41 | - | 0.940 | 1.66 | 0.95 | 2.37 | 1.21 | 0.73 | 0.014 | -1.42 | 1.40 | -0.74 | 1.37 | 0.49 | 0.040 |

| Q4. Postprandial fullness | 3.04 | 1.35 | 3.00 | 1.25 | - | 0.896 | 1.90 | 1.05 | 2.42 | 1.12 | 0.50 | 0.053 | -1.14 | 1.32 | -0.58 | 1.17 | 0.43 | 0.051 |

| Q5. Early satiation | 2.22 | 1.33 | 2.32 | 1.29 | - | 0.753 | 1.69 | 0.89 | 2.26 | 0.93 | 0.64 | 0.012 | -0.53 | 1.06 | -0.05 | 1.03 | 0.45 | 0.058 |

| FD-SS | 2.85 | 1.13 | 2.88 | 1.02 | - | 0.899 | 1.73 | 0.82 | 2.36 | 0.82 | 0.77 | 0.002 | -1.13 | 1.08 | -0.53 | 0.83 | 0.57 | 0.004 |

| Q6. Eating | 1.94 | 1.05 | 1.89 | 0.99 | - | 0.841 | 1.35 | 0.69 | 1.63 | 0.68 | 0.40 | 0.095 | -0.59 | 0.92 | -0.26 | 0.81 | 0.36 | 0.101 |

| Q7. Sleeping | 2.10 | 1.05 | 2.21 | 1.08 | - | 0.679 | 1.23 | 0.55 | 1.84 | 1.01 | 1.02 | 0.010 | -0.88 | 1.00 | -0.37 | 0.90 | 0.51 | 0.022 |

| Q8. Daily activity | 1.97 | 1.01 | 2.00 | 0.94 | - | 0.881 | 1.26 | 0.59 | 1.95 | 0.91 | 1.10 | 0.001 | -0.71 | 1.04 | -0.05 | 0.40 | 0.67 | < 0.0001 |

| Q9. Mood | 2.55 | 1.08 | 2.42 | 0.84 | - | 0.534 | 1.51 | 0.78 | 2.05 | 0.85 | 0.70 | 0.008 | -1.05 | 1.08 | -0.37 | 0.50 | 0.65 | < 0.0001 |

| Dissatisfaction for daily life-SS | 2.13 | 0.83 | 2.13 | 0.84 | - | 0.989 | 1.34 | 0.53 | 1.87 | 0.77 | 0.95 | 0.004 | -0.81 | 0.78 | -0.26 | 0.43 | 0.73 | < 0.0001 |

| Effect size | Small | Medium | Large | |||||||||||||||

| Cohen's d | 0.2 ≤ | 0.5 ≤ | 0.8 ≤ | |||||||||||||||

The responsiveness to PPI therapy was evaluated by comparing the scores for each GERD-TEST item/subscale between baseline and after 4 wk of PPI therapy. Significant differences were observed for all the GERD-TEST item/subscale scores between baseline and after 4 wk of PPI therapy, and the effect sizes, as determined using Cohen’s d, were substantial (i.e., 1.29-1.63 for GERD symptoms, 0.42-1.11 for FD symptoms, and 0.61-1.05 for dissatisfaction) (Table 5).

The concurrent validity of the GERD-TEST was evaluated by comparing the changes in the GERD-TEST scores of the treatment responders and those of the treatment non-responders according to three different responder definitions. The treatment responders demonstrated a statistically significant greater change in their scores than the treatment non-responders for all the GERD symptom items/subscale and for most of the FD and DS items/subscales (Tables 6-8).

The results of a multiple regression analysis revealed that the GERD-SS score changes had larger β values than the FD-SS score changes for Q11 (0.371 vs 0.037) and Q12 (0.411 vs -0.092), reflecting the response to therapy and indicating that GERD symptoms can be well differentiated from FD symptoms in GERD patients.

Approximately 85% of reports from GERD patients recruited under the Montreal definition were diagnosed as having GERD based on the results of the GERD-TEST, providing evidence in support of the diagnostic usefulness of the GERD-TEST. The Cronbach’s α for GERD-SS, FD-SS, and DS-SS in the GERD-TEST ranged from 0.75 to 0.82, indicating a superior internal consistency and high reliability. Significant correlations were observed between symptom or living status items/subscales of the GERD-TEST and the PCS or MCS of the SF-8, demonstrating a good convergent validity. Both GERD and FD symptoms were seen to have a clear and consistently negative impact on the daily lives of patients, and this impact increased with increasing symptom severity (Table 4). There was a significant and marked reduction in GERD symptoms in response to the 4-wk PPI therapy. Improvements in FD symptoms and daily living status were also significant, though to a lesser extent than the amelioration of GERD symptoms. Thus, the responsiveness of the GERD-TEST to these improvements was gratifying. A comparison between responders and non-responders according to three definitions of responders (a residual symptom rate ≤ 50%, a patient’s impression that was “improved” or better, and an NRS score ≤ 5) revealed significant and substantial differences in GERD symptoms between these two groups, thereby indicating that the GERD-TEST has a satisfactory concurrent validity.

The GERD-TEST enabled a multifaceted evaluation not only of the severity of symptoms, but also of the impact of the symptoms on daily life, the therapeutic response as assessed by the patient. The GERD-TEST is expected to be a useful diagnostic/treatment tool for both clinical research and in daily clinical practice settings, since it consists of relatively few items and subscales that are readily understandable and enable the detection of concurrent FD symptoms.

Symptoms of FD are often seen in patients with GERD[7-11]. The present study results showed that concurrent FD symptoms were noted in as many as 76% of the patients with GERD who met the Montreal definitions, and this finding is consistent with previous reports[7-11]. Symptoms of GERD are generally known to affect various aspects of daily living[5,6], and symptoms of FD have similarly been reported to interfere with the daily living status of patients[13-15], resulting in a reduction in QOL. In the present study, the results of a correlation analysis revealed that both GERD and FD symptoms impair the daily life of patients, affecting eating, sleeping, daily activity and mood (Table 4); these results support those reported by others[5,6,13-15]. Even if a patient presents with a chief complaint of GERD symptoms at the time of their first visit, the possibility that the patient’s QOL might be lowered because of concurrent FD and GERD symptoms still exists. Therefore, cases should be carefully selected by observing both FD symptoms and GERD symptoms, and appropriate treatment aimed at treating the former condition should also be administered simultaneously.

Inasmuch as it is often difficult to identify concurrent FD symptoms in patients with GERD, the use of an appropriate PRO might enable such symptoms to not be overlooked, allowing appropriate treatment to proceed. Based on the assumption that GERD and FD are diseases with a spectrum of overlapping symptoms[7-11], the GERD-TEST may allow clinicians to use only one PRO instrument to measure health-related QOL outcomes in patients with GERD, FD, or overlapping symptoms of both conditions.

The use of an appropriate PRO tool for which both reliability and validity have been verified is recommended to ensure evidence-based evaluations of the usefulness of a treatment for disorders such as GERD and FD, where the treatment is primarily aimed at symptomatic improvement[16]. Many PRO tools have been developed and applied in various clinical trials as well as in daily clinical practice settings for the diagnosis of GERD and for evaluating therapeutic responses[18,20]. The practical use and dissemination of PRO as a diagnostic and evaluation tool is anticipated; however, most PROs are lengthy and complicated, and a simple and effective PRO was previously unavailable. The GERD-TEST was developed for this reason.

The goal of treatment for NERD, FD and IBS lies in improving symptoms and signs characteristic of each of these disorders and thereby lessening a patient’s sense of burden and impairment of daily living activities. A variety of sets of criteria have been used to evaluate responses to pharmacotherapies for those disorders. Global binary endpoints (a method in which an alternative response to each question is provided, i.e., whether an adequate or satisfactory relief of symptoms has or has not been obtained) and a “residual symptom rate ≤ 50%” have both exhibited an intense convergent validity and are capable of detecting clinically significant but minimal changes[27]; therefore, these variables are recommended[19,28-30].

A NRS, which is mainly used to evaluate therapeutic responses in patients with chronic pain[31], has been proposed by the FDA as a provisional scale for evaluating abdominal pain in patients with irritable bowel syndrome[32]. An NRS has been recognized as having “higher compliance rates, better responsiveness and ease of use, and good applicability relative to a visual analogue scale”.

For evaluating the burden by the symptoms as well as the response to the therapy, the GERD-TEST can be applied using three definitions: i.e., a 7-point Likert scale for individual symptoms, the patient’s impression of the therapy (which corresponds to the OTE), and the NRS (as recommended by various reports and guidelines), and interestingly, the global assessments of the GERD symptoms using patient’s impression of the therapy (Q11) and NRS (Q12) well differentiated from those of FD symptoms (Table 9). Therefore, evaluations of patient burden arising from various symptoms and of the comprehensive therapeutic response using this tool are thought to be appropriate.

| Q11. Patient's impression | Q12. Numeric rating scale | |||

| β | P value | β | P value | |

| ΔGERD-SS (0-4 wk) | 0.371 | < 0.0001 | 0.411 | < 0.0001 |

| ΔFD-SS (0-4 wk) | 0.037 | 0.6541 | -0.092 | 0.2656 |

| R2 (P value) | 0.155 | < 0.0001 | 0.133 | < 0.0001 |

| Effect size | Small | Medium | Large | |

| β | 0.1 ≤ | 0.3 ≤ | 0.5 ≤ | |

| R2 | 0.02 ≤ | 0.13 ≤ | 0.26 ≤ | |

Of the plurality of therapeutic response evaluation definitions currently available, none have been shown to be optimal for the evaluation of therapeutic responses during the management of GERD. It is thus considered preferable to report data obtained and analyzed using two or more therapeutic response evaluation definitions, rather than any single definition.

The limitations of this study were, firstly, the clinical responses in terms of the GERD symptoms can be evaluated using three definitions in the GERD-TEST; these definitions were formulated chiefly for the diagnosis and treatment of GERD. Concurrent FD symptoms, however, can only be evaluated using a residual symptom rate. The GERD-TEST should be modified to include the patient’s impression and NRS items for FD symptom, similar to the GERD symptom evaluations, to make this definition even more useful for the diagnosis and treatment of FD. Secondly, it is generally recognized that patients with GERD or FD present with diverse symptoms. Among patients with GERD, non-typical symptoms such as esophageal symptoms (e.g., chest pain) and extraesophageal symptoms (e.g., chronic cough, chronic laryngitis, asthma or dental erosion[1] are often seen. Symptoms such as bloating, belching or nausea develop among patients with FD. Clinical evaluation using the GERD-TEST is focused primarily on the cardinal symptoms of GERD and FD, and the evaluation does not cover patient burden from other symptoms or the impacts of such symptoms on daily life. Further investigation and clarification of these matters is also needed.

In conclusion, the psychometric characteristics of the GERD-TEST were excellent, demonstrating good validity and reliability. The GERD-TEST is simple and easy to perform and is a multifaceted PRO instrument that appears to be useful for evaluating disease-specific health-related QOL in GERD patients in both clinical trial and primary care settings.

This study was conducted by the GERD Society and registered to UMIN-CTR #000006614. Financial support for this clinical study was provided by GERD Society (Osaka, Japan). This study was completed by 29 institutions in Japan. The results of this study were presented at the Digestive Disease Week 2017, Chicago, United States. The authors thank all physicians who participated in this study and the patients whose cooperation made this study possible. The contributor of each institution is listed below.

Nobuyuki Matsuhashi, NTT Medical Center Tokyo; Mineo Kudo, Sapporo Hokuyu Hospital; Norimasa Yoshida and Takahiro Suzuki, Japanese Red Cross Kyoto Daiichi Hospital; Kazunari Murakami and Seiji Shiota, Oita University Faculty of Medicine; Mototsugu Kato and Katsuhiro Mabe, Hokkaido University Hospital; Tsuyoshi Sanuki and Junko Hori, Kita Harima Medical Center; Noriaki Manabe and Ken Haruma, Kawasaki Medical School; Yuji Naito and Osamu Handa, Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine; Syuuji Inoue, National Hospital Organization Kochi Hospital; Hirokazu Oyamada and Yutaka Isozaki, Matsushita Memorial Hospital; Shuichi Muto, Tomakomai City Hospital; Kenji Furuta and Shunji Ohara, Shimane University Faculty of Medicine; Tadayuki Oshima and Hiroto Miwa, Hyogo College of Medicine; Yasuhiro Fujiwara and Yukie Kohata, Osaka City University Graduate School of Medicine; Kazuhiro Maeda and Yuji Sakai, Tenjin Clinic, Medical Corporation Shin-ai; Yugo Iwaya and Sadahisa Okuhara, Shinshu University School of Medicine; Takashi Abe and Yongmin Kim, Takarazuka Municipal Hospital; Hideki Mizuno, Toyama City Hospital; Kimio Isshi, Isshi Gastro-Intestinal Clinic; Hiroshi Seno and Tsutomu Chiba, Kyoto University Hospital; Fukunori Kinjo and Manabu Nakamoto, University Hospital, University of the Ryukyus; Toshiro Sugiyama and Haruka Fujinami, University of Toyama; Keiko Utsumi, Aichi Medical University Medical Clinic; Hiroyuki Kuwano and Tatsuya Miyazaki, Gunma University Hospital; Noriko Watanabe, National Hospital Organization Mie Chuo Medical Center; Fumihiko Kinekawa and Kita Yuko, Sanuki Municipal Hospital; Tomonori Imaoka and Hirohumi Fujishiro, Shimane Prefectural Central Hospital; Takatsugu Yamamoto and Yasushi Kuyama, Teikyo University School of Medicine; Yasuaki Nakajima and Kenro Kawada, Tokyo Medical and Dental University.

The use of an appropriate patient-reported outcome (PRO) instrument may facilitate the detection of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) patients, and the evaluation of the disease’s impact on daily life and the response to the therapy. However, a simple and effective PRO was previously unavailable.

The importance of PRO in evaluating medical care has been stressed in recent years. The Food and Drug Administration guidance recommends the use of valid and appropriate PRO for each disease.

Most of the previously developed PROs for GERD were lengthy and complicated, and even not well validated. The lack of a simple, easy to understand instrument for GERD patients encouraged the development of the gastroesophageal reflux and dyspepsia therapeutic efficacy and satisfaction test (GERD-TEST). The GERD-TEST minimized the number of items and enabled a multifaceted evaluation not only of the severity of symptoms, but also of the impact of the symptoms on daily life and of the therapeutic response as assessed by the patient. The psychometric characteristics of the GERD-TEST were excellent, demonstrating good validity and reliability.

This study indicated that the GERD-TEST is a useful tool for the clinical research in GERD patients. Since the GERD-TEST is simple and easy-to-understand, which also could applied for daily clinical practice settings.

The PRO instrument with proven reliability and validity is useful for the disorders in which the treatment goal is to ameliorate symptoms. The application of PRO not only in clinical trials, but also in daily clinical practice settings would enable greater objectivity in the diagnosis and evaluation of therapeutic responses in GERD cases and the provision of effective and efficient treatment.

The study is well done and the methodology is strong. The clinical meaning is also relevant, because the authors have addressed the frequent overlap between esophageal and dyspepsia symptoms. This investigation merits to be published.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Savarino V S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF

| 1. | Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R; Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900-1920; quiz 1943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2368] [Cited by in RCA: 2453] [Article Influence: 129.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Fujiwara Y, Arakawa T. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of GERD in the Japanese population. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:518-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Manabe N, Haruma K, Kamada T, Kusunoki H, Inoue K, Murao T, Imamura H, Matsumoto H, Tarumi K, Shiotani A. Changes of Upper Gastrointestinal Symptoms and Endoscopic Findings in Japan Over 25 Years. Internal Medicine. 2011;50:1357-1363. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Miwa H, Oshima T, Tomita T, Kim Y, Hori K, Matsumoto T. Gastro-esophageal reflux disease: the recent trend in Japan. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2008;1:133-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bytzer P. Goals of therapy and guidelines for treatment success in symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:S31-S39. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Velanovich V. Quality of life and severity of symptoms in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a clinical review. Eur J Surg. 2000;166:516-525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Choung RS, Locke GR 3rd, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Talley NJ. Overlap of dyspepsia and gastroesophageal reflux in the general population: one disease or distinct entities? Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:229-234, e106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Fujiwara Y, Arakawa T. Overlap in patients with dyspepsia/functional dyspepsia. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;20:447-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Haque M, Wyeth JW, Stace NH, Talley NJ, Green R. Prevalence, severity and associated features of gastro-oesophageal reflux and dyspepsia: a population-based study. N Z Med J. 2000;113:178-181. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Kaji M, Fujiwara Y, Shiba M, Kohata Y, Yamagami H, Tanigawa T, Watanabe K, Watanabe T, Tominaga K, Arakawa T. Prevalence of overlaps between GERD, FD and IBS and impact on health-related quality of life. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1151-1156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ohara S, Kawano T, Kusano M, Kouzu T. Survey on the prevalence of GERD and FD based on the Montreal definition and the Rome III criteria among patients presenting with epigastric symptoms in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:603-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Savarino E, Pohl D, Zentilin P, Dulbecco P, Sammito G, Sconfienza L, Vigneri S, Camerini G, Tutuian R, Savarino V. Functional heartburn has more in common with functional dyspepsia than with non-erosive reflux disease. Gut. 2009;58:1185-1191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Aro P, Talley NJ, Agréus L, Johansson SE, Bolling-Sternevald E, Storskrubb T, Ronkainen J. Functional dyspepsia impairs quality of life in the adult population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:1215-1224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Haag S, Senf W, Häuser W, Tagay S, Grandt D, Heuft G, Gerken G, Talley NJ, Holtmann G. Impairment of health-related quality of life in functional dyspepsia and chronic liver disease: the influence of depression and anxiety. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:561-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Talley NJ, Verlinden M, Jones M. Validity of a new quality of life scale for functional dyspepsia: a United States multicenter trial of the Nepean Dyspepsia Index. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2390-2397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Guidance for Industry. Patient-Reported Outcomes Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf. |

| 17. | Corsetti M, Tack J. FDA and EMA end points: which outcome end points should we use in clinical trials in patients with irritable bowel syndrome? Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25:453-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Fass R. Symptom assessment tools for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) treatment. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:437-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Irvine EJ, Tack J, Crowell MD, Gwee KA, Ke M, Schmulson MJ, Whitehead WE, Spiegel B. Design of Treatment Trials for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1469-1480.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Vakil NB, Halling K, Becher A, Rydén A. Systematic review of patient-reported outcome instruments for gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:2-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hongo M. Minimal changes in reflux esophagitis: red ones and white ones. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:95-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hoshihara H. GERD-gastroesophageal reflux disease. Endoscopic diagnosis and classification. Rinshou Shoukakinaika. 1996;11:1563-1568. |

| 23. | Matsuhashi N, Kudo M, Yoshida N, Murakami K, Kato M, Sanuki T, Oshio A, Joh T, Higuchi K, Haruma K. Factors affecting response to proton pump inhibitor therapy in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease: a multicenter prospective observational study. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:1173-1183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Turner-Bowker DM, Bayliss MS, Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M. Usefulness of the SF-8 Health Survey for comparing the impact of migraine and other conditions. Qual Life Res. 2003;12:1003-1012. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361-370. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:155-159. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Spiegel B, Camilleri M, Bolus R, Andresen V, Chey WD, Fehnel S, Mangel A, Talley NJ, Whitehead WE. Psychometric evaluation of patient-reported outcomes in irritable bowel syndrome randomized controlled trials: a Rome Foundation report. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1944-1953.e1-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ang D, Talley NJ, Simren M, Janssen P, Boeckxstaens G, Tack J. Review article: endpoints used in functional dyspepsia drug therapy trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:634-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Camilleri M, Mangel AW, Fehnel SE, Drossman DA, Mayer EA, Talley NJ. Primary endpoints for irritable bowel syndrome trials: a review of performance of endpoints. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:534-540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Vakil N, Laine L, Talley NJ, Zakko SF, Tack J, Chey WD, Kralstein J, Earnest DL, Ligozio G, Cohard-Radice M. Tegaserod treatment for dysmotility-like functional dyspepsia: results of two randomized, controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1906-1919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ritter PL, González VM, Laurent DD, Lorig KR. Measurement of pain using the visual numeric scale. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:574-580. [PubMed] |

| 32. | US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Guidance for Industry: Irritable Bowel SyndromeClinical Evaluation of Drugs for Treatment. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/ Guidances/UCM205269.pdf. |