Published online Apr 21, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i15.4362

Revised: December 31, 2013

Accepted: January 20, 2014

Published online: April 21, 2014

Processing time: 148 Days and 19 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the efficacy and safety of esomeprazole-based triple therapy compared with lansoprazole therapy as first-line eradication therapy for patients with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) in usual post-marketing use in Japan, where the clarithromycin (CAM) resistance rate is 30%.

METHODS: For this multicenter, randomized, open-label, non-inferiority trial, we recruited patients (≥ 20 years of age) with H. pylori infection from 20 hospitals in Japan. We randomly allocated patients to esomeprazole therapy (esomeprazole 20 mg, CAM 400 mg, amoxicillin (AC) 750 mg for the first 7 d, with all drugs given twice daily) or lansoprazole therapy (lansoprazole 30 mg, CAM 400 mg, AC 750 mg for the first 7 d, with all drugs given twice daily) using a minimization method with age, sex, and institution as adjustment factors. Our primary outcome was the eradication rate by intention-to-treat (ITT) and per-protocol (PP) analyses. H. pylori eradication was confirmed by a urea breath test from 4 to 8 wk after cessation of therapy.

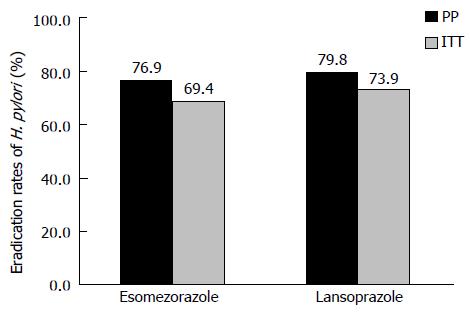

RESULTS: ITT analysis revealed the eradication rates of 69.4% (95%CI: 61.2%-76.6%) for esomeprazole therapy and 73.9% (95%CI: 65.9%-80.6%) for lansoprazole therapy (P = 0.4982). PP analysis showed eradication rate of 76.9% (95%CI: 68.6%-83.5%) for esomeprazole therapy and 79.8% (95%CI: 71.9%-86.0%) for lansoprazole therapy (P = 0.6423). There were no differences in adverse effects between the two therapies.

CONCLUSION: Esomeprazole showed non-inferiority and safety in a 7 day-triple therapy for eradication of H. pylori compared with lansoprazole.

Core tip: Amoxicillin is a standard regime for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication in Japan. Esomeprazole is a second-generation PPI that became available in 2011 in Japan. Several studies have reported eradication data comparing esomeprazole to first-generation proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), but it is not known whether the H. pylori eradication rates of esomeprazole are equal to those of lansoprazole, a first-generation PPI, under circumstances of increased resistance to clarithromycin in Japan.

-

Citation: Nishida T, Tsujii M, Tanimura H, Tsutsui S, Tsuji S, Takeda A, Inoue A, Fukui H, Yoshio T, Kishida O, Ogawa H, Oshita M, Kobayashi I, Zushi S, Ichiba M, Uenoyama N, Yasunaga Y, Ishihara R, Yura M, Komori M, Egawa S, Iijima H, Takehara T. Comparative study of esomeprazole and lansoprazole in triple therapy for eradication of

Helicobacter pylori in Japan. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(15): 4362-4369 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i15/4362.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i15.4362

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are widely used for the treatment of acid-peptic diseases. Their mechanism of action involves inhibition of the H-K-adenosine triphosphatase enzyme in the parietal cells of the gastric mucosa. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication therapy is effective for accelerating healing and inhibiting the recurrence of gastric or duodenal ulcers, and is strongly recommended in various guidelines as a first-line therapy for H. pylori-positive gastric or duodenal ulcers[1,2]. Treatment with PPIs in combination with antibiotics has increased the eradication rate of H. pylori[3,4]. Acid inhibition increases eradication efficacy because antibiotics are more stable in a less acidic gastric environment and induces a higher antibiotic sensitivity in the bacteria[5].

PPI-containing triple therapy with clarithromycin (CAM) and amoxicillin (AC) is a standard regime for H. pylori eradication in Japan. This triple therapy in patients with gastric or duodenal ulcers has been covered under Japan’s national health insurance scheme since 2000, and in 2013 its indication was expanded for H. pylori eradication, including H. pylori-positive atrophic gastritis. In 2007, a second-line eradication therapy, substituting metronidazole (MTZ) for CAM was also approved. The recent subsequent increase in bacterial resistance to CAM in Japan, however, led to a decline in the eradication rate by first-line therapy[6]. The Japanese Society for Helicobacter Research conducted a CAM sensitivity study to examine the prevalence of bacterial resistance from 2002 to 2006 in Japan. Surveillance revealed that the CAM resistance rate was 18.9% from 2002 to 2003, and then gradually increased to 21.1% from 2003 to 2004, to 27.7% from 2004 to 2005[7]. Due to the increased resistance to CAM, it is recommended that drug sensitivity tests be performed before initiating eradication therapy. Sensitivity tests are not common, however, because other antibiotics are not approved for first-line eradication therapy.

Esomeprazole, the S-isomer of omeprazole, is a second-generation PPI that became available in 2011 in Japan. Esomeprazole is considered to induce greater acid secretion suppression than first-generation PPIs because of pharmacologic advantages over the racemic compound[8], and is less likely to be affected by CYP2C19 polymorphisms[9]. Several studies have reported eradication data comparing esomeprazole to first-generation PPIs[10], but it is not known whether the H. pylori eradication rates of esomeprazole are equal to those of lansoprazole, a first-generation PPI, under circumstances of increased resistance to CAM. Therefore, in this study, we compared 7 d triple therapy with esomeprazole or lansoprazole containing AC and CAM.

This was a prospective, randomized, controlled study. At baseline, patients were evaluated for inclusion and exclusion criteria and written informed consent was obtained. Patients aged at least 20 years, diagnosed with gastric ulcers, duodenal ulcers, or gastric mucosa associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, or early gastric cancer with H. pylori infections who met the inclusion criteria and who wished to receive eradication therapy for H. pylori were enrolled into the study. Those diseases are covered for H. pylori eradication by Japanese health insurance. In patients with gastric ulcers, H. pylori eradication therapy was administered after the active gastric ulcer healed because 1 wk of H. pylori eradication therapy is insufficient to heal gastric ulcers[11]. In patients with active duodenal ulcers, however, 1 wk of H. pylori eradication therapy is considered sufficient[12].

At entry, a patient was diagnosed as H. pylori-positive if at least one of the following tests was positive histochemically-detectable H. pylori (hematoxylin and eosin staining), rapid urease test, urea breath test, or stool antigen test. Exclusion criteria were as follows: past history of drug allergy to PPIs, AC or CAM; previous therapy for H. pylori; clinically significant renal or hepatic disease, or any other clinically significant medical condition that could increase risk; pregnancy; alcohol abuse; drug addiction; and previous partial or total gastrectomy.

Patients were enrolled by a gastroenterologist at each participating institute after assessment of the appropriate indications and ruling out any contraindications to the therapies. Patients were then randomly allocated to the esomeprazole group (esomeprazole 20 mg, CAM 400 mg, AC 750 mg for the first 7 d; with all drugs given twice daily) or lansoprazole therapy (lansoprazole 30 mg, CAM 400 mg, AC 750 mg for the first 7 d; with all drugs given twice daily) by the minimization method with age, sex, and institution as adjustment factors, using an allocation system, Waritsuke-kun® (Mebix, Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The dose of CAM could be reduced to 200 mg twice daily at the attending doctor’s discretion according to patients age or physical size. Adverse events (AE) were evaluated using the Common Terminology Criteria version 4.0. Compliance was measured based on patient’s medication diary at each visit. Compliance was calculated using the following formula: compliance = actual number of internal use/14 (total number of internal use/7 d) × 100 (%).

Determination of eradication was made from 4 to 8 wk after the completion of eradication therapy. Determination of H. pylori eradication was made using a urea breath test but measurement of H. pylori antigen in the feces could be used instead of the urea breath test according to institution availability. The eradication rate was defined as the number of successfully treated patients divided by the number of all treated patients.

The study was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by each institution’s ethics committee. This trial is registered with UMIN Clinical trials: http://www.umin.ac.jp/ctr/, number UMIN000007733. Signed informed consent was obtained from each patient before study enrollment.

The trial was designed as a non-inferiority trial to compare a 7 d triple therapy with esomeprazole vs lansoprazole, AC, and CAM for H. pylori infection in patients naïve to therapy. The eradication rate was evaluated by intention-to-treat (ITT) and per protocol (PP). In the ITT analysis, all enrolled patients that were lost during follow-up or did not get the breath test or stool antigen test to evaluate eradication or withdrew due to AE were classified as failed to eradicate.

Our primary outcome was the eradication rate by ITT and PP analyses of the two therapies. The secondary outcomes were drug adherence and adverse events. In the PP analysis, patients who were lost during follow-up or did not follow the protocol were excluded from the analyses.

We calculated the sample size based on a non-inferiority margin of 10%, a successful eradication rate of at least 70%, a two-sided test at the 5% level, and a power of 80%. Based on this, a sample size of 119 patients per therapy group was calculated to be sufficient. We decided to increase the number to 130 patients per therapy group, however, to compensate for a potential 10% loss at follow-up.

The significance level was set at P < 0.05. The 95%CI were constructed by normal approximation. Univariate logistic regressions were performed to predict successful eradication. Statistical analysis was performed using JMP software (ver. 10.0.2d1, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

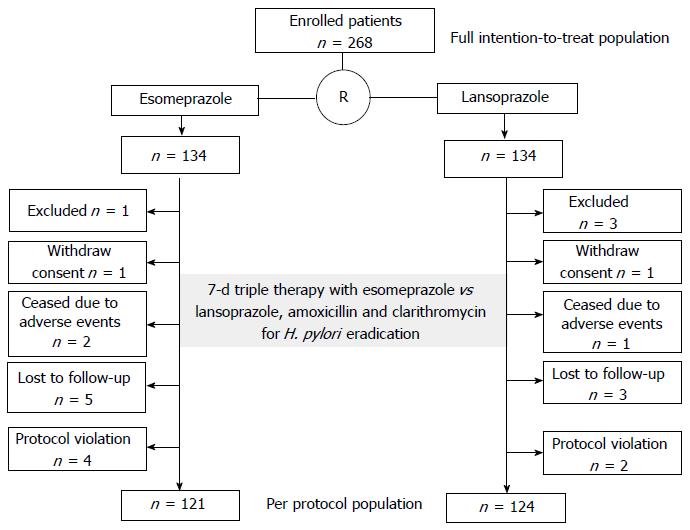

In total, 268 patients evaluated at 20 hospitals attending the Osaka Gut Forum were enrolled from May 2012 to February 2013 (Table 1). We randomly assigned the patients to receive esomeprazole therapy (n = 134) or lansoprazole therapy (n = 134) (Figure 1). Patients were diagnosed with gastric ulcers (n = 163), duodenal ulcers (n = 59), both gastric and duodenal ulcers (n = 7), gastric mucosa associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (n = 2), idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (n = 1), or early gastric cancer after endoscopic therapy (n = 36) with H. pylori infection at entry. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients in the two groups were comparable (Table 2). Mean age ± SD was 61 ± 14 years. There were 186 men (69%). There were no significant differences found in age, sex, body mass index, smoking habit, alcohol use, underlying diseases, or CAM dose between the two groups.

| Hospital | Patients (esomeprazole/lansoprazole) | % | |

| 1 | Osaka Kaisei Hospital | 52 (28/24) | 19.4 |

| 2 | Itami City Hospital | 39 (20/19) | 14.6 |

| 3 | Osaka University Hospital | 26 (12/14) | 10.1 |

| 4 | Osaka Seamen’s Insurance Hospital | 24 (11/13) | 9.0 |

| 5 | Ashiya Municipal Hospital | 17 (6/11) | 6.3 |

| 6 | Osaka General Medical Center | 17 (7/10) | 6.3 |

| 7 | Yao Municipal Hospital | 16 (9/7) | 6.0 |

| 8 | Osaka National Hospital | 13 (7/6) | 4.9 |

| 9 | Sumitomo Hospital | 11 (6/5) | 4.1 |

| 10 | Nishinomiya Municipal Central Hospital | 9 (4/5) | 3.4 |

| 11 | Osaka Police Hospital | 7 (3/4) | 2.6 |

| 12 | Higashiosaka City General Hospital | 6 (2/4) | 2.2 |

| 13 | Ikeda Municipal Hospital | 6 (3/3) | 2.2 |

| 14 | Toyonaka Municipal Hospital | 6 (3/3) | 2.2 |

| 15 | Otemae Hospital | 5 (3/2) | 1.9 |

| 16 | Hyogo Prefectural Nishinomiya Hospital | 4 (2/2) | 1.5 |

| 17 | Osaka Medical Center for Cancer and Cardiovascular Disease | 4 (1/3) | 1.5 |

| 18 | Minoh City Hospital | 3 (1/2) | 1.1 |

| 19 | Osaka Rosai Hospital | 2 (1/1) | 0.7 |

| 20 | Kansai Rosai Hospital | 1 (0/1) | 0.4 |

| Total | 268 (134/134) | 100 |

| Characteristics | Total patients n = 268 | Esomeprazole therapy n = 134 | Lansoprazole therapy n = 134 |

| Age (yr) (mean ± SD) range | 61 ± 14 23-92 | 61 ± 13 25-84 | 61 ± 14 23-92 |

| Sex, male, % | 186, 69% | 92, 69% | 94, 70% |

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 22.9 ± 3.5 | 22.7 ± 3.5 | 23.0 ± 3.5 |

| Alcohol1, n, (%) | 119, 44% | 54, 42% | 65, 49% |

| Smoking (%) | 75, 28% | 37, 28% | 38, 28% |

| Underlying diseases | |||

| Hypertension, n, % | 69, 26% | 35, 26% | 34, 25% |

| Diabetes mellitus, n, % | 35, 13% | 18, 13% | 17, 13% |

| Lipid disorder, n, % | 31, 12% | 12, 9% | 19, 14% |

| Chronic lung disease, n, % | 7, 3% | 4, 3% | 3, 2% |

| Disease for H. pylori eradication | |||

| Gastric ulcer, n, % | 163, 61% | 82, 61% | 81, 61% |

| Duodenal ulcer, n, % | 59, 22% | 29, 22% | 30, 22% |

| Gastroduodenal ulcer, n, % | 7, 3% | 5, 4% | 2, 1.5% |

| Gastric MALT lymphoma, n, % | 2, 0.7% | 0, 0% | 2, 1.5% |

| ITP, n, % | 1, 0.4% | 1, 0.8% | 0, 0% |

| EGC after endoscopic therapy, n, % | 36, 13% | 17, 13% | 19, 14% |

| Therapy and test for H. pylori eradication | |||

| Clarithromycin 400 mg/800 mg per day | 28/233 | 12/118 | 16/115 |

| Urea breath test/stool antigen test/others | 230/17/4 | 113/8/3 | 117/9/1 |

| Compliance2 | |||

| Good, n, % | 226 (84%) | 110 (82%) | 116 (87%) |

For the initial determination of H. pylori infection status, a rapid urease test was performed in 113 patients (42%), blood antibody test in 110 patients (41%), stool antigen test in 7 patients (2.6%), histopathology of biopsy specimens in 25 (9.3%) patients, and urea breath test in 13 patients (4.9%). Figure 1 shows the flow chart for this study. After randomization, 4 patients were excluded 2 patients in the lansoprazole group had a history of gastrectomy, 1 patient in the lansoprazole group had comorbid gastric cancer, and 1 patient in the esomeprazole group had a history of penicillin allergy. One patient in each group withdrew their informed consent before therapy. Two patients in the esomeprazole and 1 patient in the lansoprazole group withdrew due to adverse effects (Grade 3 vomiting and Grade 1 diarrhea in the esomeprazole group and Grade 1 vomiting in the lansoprazole group). Three patients in the lansoprazole group and 5 patients in the esomeprazole group were lost to follow-up. Two patients in the lansoprazole group and four in the esomeprazole group were excluded due to a protocol violation about judging method for H. pylori eradication or internal method (Figure 1).

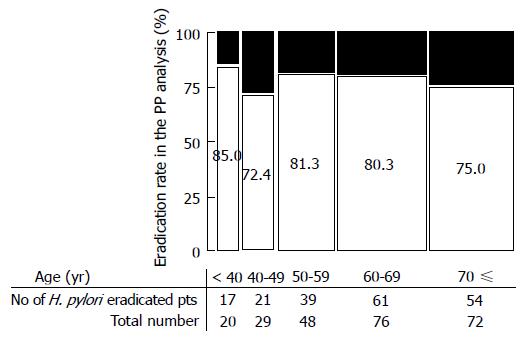

The efficacy of the two eradication therapies is shown in Figure 2. ITT analysis showed eradication rates 69.4% (95%CI: 61.2%-76.6%) for esomeprazole therapy and 73.9% (95%CI: 65.9%-80.6%) for lansoprazole therapy. The PP eradication rate was 76.9% (95%CI: 68.6%-83.5%) for esomeprazole therapy and 79.8% (95%CI: 71.9%-86.0%) for lansoprazole therapy. Comparisons of the two therapies, both in the ITT and PP analyses, showed non-inferiority (ITT, P = 0.4982; PP, P = 0.6423). Univariate logistic regression analysis showed that there were no predicting factors (sex, age, habit of smoking or alcohol, body mass index, dose of CAM, and underling diseases) for successful eradication (Table 3). Figure 3 shows eradication rates in the PP analysis stratified by age.

| OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1 | ||

| Female | 0.963 | 0.507-1.88 | 0.909 |

| Age (yr) | |||

| < 60 | 1 | ||

| ≥ 60 | 1.1 | 0.594-2.09 | 0.754 |

| Smoking | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.14 | 0.578-2.38 | 0.708 |

| Drinking | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.644 | 0.347-1.18 | 0.157 |

| BMI | |||

| < 25 | |||

| ≥ 25 | 0.73 | 0.361-1.52 | 0.387 |

| Clarithromycin | |||

| 400 mg/d | 1 | ||

| 800 mg/d | 1.96 | 0.752-4.75 | 0.162 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.665 | 0.295-1.61 | 0.352 |

| Hypertension | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.64 | 0.336-1.28 | 0.209 |

| Lipid disorder | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.75 | 0.638-6.16 | 0.295 |

| Chronic lung disease | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.68 | 0.278-32.0 | 0.616 |

The incidence of AE was comparable between the two therapies (Table 4). The incidence of AE incidence of all grades was 56% (75/134) in the esomeprazole group and 53% (71/134) in the lansoprazole group. Most AEs were Grade 1 (85% in both groups). In both groups, diarrhea was the AE with highest incidence (27% in the esomeprazole group and 31% in the lansoprazole group). AEs were severe enough to discontinue therapy in 2 patients (1.4%) in the esomeprazole group and 1 (0.7%) in the lansoprazole group. One patient stopped therapy due to Grade 1 diarrhea. One patient in the lansoprazole group had Grade 3 diarrhea, but discontinued to take the medicine every day or every other day based on his own judgment. He was excluded from the PP analysis due to a protocol violation. Compliance of all patients except for 3 patients (50%, 79%, 86%) was 100% in the PP population and excellent based on all the patients’ medication diaries.

| Adverse events | Esomeprazole therapy | Lansoprazole therapy | ||||||

| G1 | G2 | G3 | Total, % | G1 | G2 | G3 | Total, % | |

| Diarrhea | 32 | 3 | 1 | 36, 27% | 33 | 7 | 1 | 41, 31% |

| Bitter taste | 13 | 3 | 0 | 16, 12% | 14 | 2 | 0 | 16, 12% |

| Nausea | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1, 0.7% | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1, 0.7% |

| Vomiting | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3, 2.2% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0, 0% |

| Eruption | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3, 2.2% | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3, 2.2% |

| Headache | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0, 0% | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2, 1.5% |

| Fatigue | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1, 0.7% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0, 0% |

| Appetite loss | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3, 2.2% | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1, 0.7% |

| Stomatitis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0, 0% | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1, 0.7% |

| Cheilitis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0, 0% | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2, 1.5% |

| Thirst | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2, 1.5% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0, 0% |

| Belch | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1, 0.7% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0, 0% |

| Bad breath | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1, 0.7% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0, 0% |

| Sore throat | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1, 0.7% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0, 0% |

| Joint paint | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1, 0.7% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0, 0% |

| Leg edema | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0, 0% | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1, 0.7% |

| Chest discomfort | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2, 1.5% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0, 0% |

| Floating | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1, 0.7% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0, 0% |

| Abdominal wind | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1, 0.7% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0, 0% |

| Constipation | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2, 1.5% | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2, 1.5% |

| Pruritus ani | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0, 0% | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1, 0.7% |

| Total | 64 | 9 | 2 | 75, 56% | 60 | 10 | 1 | 71, 53% |

The present study compared esomeprazole and lansoprazole therapy in H. pylori eradication. Generally, PPIs are used for H. pylori eradication. Two mechanisms are assumed to underlie the increased eradication rate: enhancement of antibiotic efficacy induced by acid control[10], and direct antibacterial effect of PPIs.

Omeprazole and lansoprazole (first-generation PPIs) have anti-acid properties and demonstrated efficacy for H. pylori eradication. The second-generation PPIs (rabeprazole and esomeprazole) have demonstrated even higher acid inhibition[13,14]. Kirchheiner et al[13] reported that the relative potencies of the PPIs compared to omeprazole based on mean 24 h gastric pH were 0.9 and 1.6 for lansoprazole and esomeprazole, respectively. Even though considering the difference of dose of each PPI in this study, second-generation PPIs, esomeprazole are considered to more effectively suppress acid secretion than first-generation PPIs, lansoprazole. One of the reasons is considered that esomeprazole is less likely to be affected than omeprazole by CYP2C19 polymorphisms[9]. More acid inhibition is considered to increase eradication efficacy because antibiotics are more stable in a less acidic gastric environment and induce higher antibiotic sensitivity in the bacteria[5]. Moreover, PPIs themselves may have direct antibacterial properties. Benzimidazole PPIs inhibit the growth of H. pylori[15]. Omeprazole competitively inhibits the extracellular urease enzyme of H. pylori in a dose-dependent manner[16]. Miwa et al[17] reported that rabeprazole is equivalent to omeprazole and lansoprazole in the PPI/AC triple therapy in Japan Differential inhibitory effects of esomeprazole and lansoprazole on urease, however, have not been demonstrated.

Esomeprazole, the S-isomer of omeprazole (a racemic mixture of S- and R-optical isomers), is the first PPI to be developed as a single optical isomer. Esomeprazole has been available in Japan since 2011. Esomeprazole is effective for H. pylori eradication. Our findings indicated non-inferiority and safety in 7 day-triple therapy based on esomeprazole compared with lansoprazole. A number of studies have compared esomeprazole with other first-generation PPIs. Wang et al[18] reported that the mean H. pylori eradication rate (ITT) with esomeprazole plus antibiotics was 86%, a rate comparable to that of other PPI therapies, 81% (ITT); the odds ratio (OR) was 1.38 (95%CI: 1.09-1.75) in 11 randomized controlled trials including 2159 subjects in a meta-analysis. The OR by a focused meta-analysis of six selected high-quality studies was 1.17 (95%CI: 0.89-1.54) and sub-analysis that included only studies comparing different doses of esomeprazole with omeprazole or pantoprazole revealed no significant differences[18]. Another recently meta-analysis (35 studies, 5998 patients) showed higher eradication rates for esomeprazole than for first-generation PPIs [82.3% vs 77.6%; OR = 1.32 (95%CI: 1.01-1.73)][10]. After excluding some studies due to methodological differences, the OR was increased to 1.52 (95%CI: 1.19-1.95). In sub-analyses based on esomeprazole dose, esomeprazole 40 mg twice daily had an OR of 2.27 (95%CI: 1.07-4.82), while esomeprazole 20 mg twice daily had an OR of 1.04 (95%CI: 0.80-1.1.35). Thus, it seemed that the new-generation PPIs esomeprazole or rabeprazole are more effective than first-generation PPIs, omeprazole or lansoprazole, for H. pylori eradication when using a higher dose of esomeprazole.

The most common causes for failed eradication are the presence of H. pylori resistance against antibiotics or compliance of therapy, or both. Recently, a subsequent increase in bacterial resistance to CAM was reported in Japan, leading to a decline in the eradication rate of first-line therapy[6]. Generally, the best approach for H. pylori eradication is the use of regimens that have proven to be reliably excellent locally[19]. Unfortunately, sensitivity tests are not common in Japan because antibiotics other than the PPI/AC/CAM triple therapy have not been approved for first-line eradication. The eradication rate of PPI/AC/MTZ triple therapy, which was approved as a second- line therapy has remained consistently high, about 90%[20], and eradication is successful in most patients who are positive for H. pylori infection.

The history of the patient’s prior antibiotic use and any prior therapies will also help to identify which antibiotics are likely to be successful and those for which resistance is probable. In this study, we excluded patients with prior H. pylori eradication therapy. To evaluate the patient’s antibiotic use history, we examined patients with chronic lung disease because those patients often used CAM. In the present study, however, patients background was not significantly different between groups. All but 3 patients were 100% compliant in per protocol population and compliance was excellent. Therefore, drug compliance might not have influenced the eradication rate in this study.

On the other hand, actual compliance with therapy to eradicate H. pylori can be problematic because patients often need to take as many as three different medications. Sasaki et al[21] suggested that packs of eradication medicine are useful for increasing eradication success. A drug pack, Lansap® (Takeda Chemical Industries, Ltd, Osaka, Japan) to simplify dosing has been available since 2002 in Japan. Lansap® provides daily dose cards for a 7 d therapy cycle. Each dose card contains three different prescription drugs for 1-d therapy. Nagahara et al[22] reported PP analysis using data from 57 patients in the Lansap group and 67 patients in a separate tablets group whose compliance was equal to or greater than 80%. The cure rates for the groups receiving Lansap® and the separate tablets were 86.0% (95%CI: 74%-94%) and 76.1% (95%CI: 64%-86%), respectively, in the PP analysis. The eradication rates did not differ significantly between these two groups, although the eradication rate was about 10% higher with the Lansap®. Kawai et al[23] also reported that a medication package might be useful to prevent mistakes regarding medicine dosage. In the present study, patients in the lansoprazole group could use Lansap® at the attending doctor’s discretion, whereas patients in the esomeprazole group were used separate tablets, suggesting that the packaging did not have a significant influence on the eradication efficiency. Drug compliance was suggested to be positively related to age over 60 years[24]. In the present study, however, eradication rate stratified by age was not significantly different among ages (Figure 3).

In conclusion, esomeprazole was not inferior and safe in 7 d triple therapy for eradication of H. pylori compared with lansoprazole.

Study investigators: Hideharu Ogiyama, Eriko Nakamura, Yukako Taniguchi, Yoshiko Sugimoto, Koichiro Watabe (Osaka Kaisei Hospital); Yoshito Hayashi, Tomofumi Akasaka, Motohiko Kato, Shinichiro Shinzaki (Osaka University Hospital); Yoko Murayama (Itami City Hospital); Tadaharu Takemura (Ashiya Municipal Hospital); Kosaku Ohnishi, Yasutoshi Nozaki, Osamu Nishiyama (Osaka General Medical Center); Naoki Kawai, Akiyoshi Okada (Osaka Police Hospital); Tadashi Kegasawa, Fumitaka Terabe (Yao Municipal Hospital); Tetsuya Iwasaki, Yuko Sakakibara, Takuya Yamada (Osaka National Hospital); Kazuo Kinoshita (Sumitomo Hospital); Hirofumi Kashihara (Nishinomiya Municipal Central Hospital); Katsumi Yamamoto, Shiro Hayashi, Mitsuhiko Shibuya (Toyonaka Municipal Hospital); Akihiro Nishihara(Minoh City Hospital); Daisuke Utsunomiya, Rui Mizumoto, Yasushi Matsumoto (Ikeda Municipal Hospital); Masako Sato (Osaka Rosai Hospital).

Esomeprazole is a second-generation proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) that became available in 2011 in Japan. Esomeprazole is considered to induce greater acid secretion suppression than first-generation PPIs because of pharmacologic advantages over the racemic compound. Several studies have reported eradication data comparing esomeprazole to first-generation PPIs, but it is not known whether the Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication rates of esomeprazole are equal to those of lansoprazole, a first-generation PPI, under circumstances of increased resistance to clarithromycin.

Esomeprazole, the S-isomer of omeprazole, is the first PPI to be developed as a single optical isomer. Esomeprazole is considered to more effectively suppress acid secretion than first-generation PPIs. More acid inhibition is considered to increase eradication efficacy because antibiotics are more stable in a less acidic gastric environment and induce higher antibiotic sensitivity in the bacteria.

Recently meta-analysis showed higher eradication rates for esomeprazole than for first-generation PPIs. In sub-analyses based on esomeprazole dose, esomeprazole 40 mg twice daily had higher eradication rates, while esomeprazole 20 mg twice daily did not show the significant eradication rates.

The study results showed that esomeprazole was not inferior and safe in 7-d triple therapy for eradication of H. pylori compared with lansoprazole under circumstances of increased resistance to clarithromycin in Japan.

Determination of eradication was made from 4 to 8 wk after the completion of eradication therapy. Determination of H. pylori eradication was made using a urea breath test but measurement of H. pylori antigen in the feces could be used instead of the urea breath test according to institution availability. The eradication rate was defined as the number of successfully treated patients divided by the number of all treated patients.

Generally clarithromycin-containing eradication therapy should not be considered as first-line therapy for H. pylori eradication if clarithromycin resistance rate is over 15%-20%. Unfortunately, Japanese health insurance dose not allowed other regimens but clarithromycin containing triple therapy. Therefore the regimens containing clarithromycin in the present study are standard regimens as first-line therapy for H. pylori eradication in Japan.

P- Reviewers: Imaeda H, Kuo FC, Matsukawa J S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Asaka M, Kato M, Takahashi S, Fukuda Y, Sugiyama T, Ota H, Uemura N, Murakami K, Satoh K, Sugano K. Guidelines for the management of Helicobacter pylori infection in Japan: 2009 revised edition. Helicobacter. 2010;15:1-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 282] [Cited by in RCA: 294] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, Atherton J, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gensini GF, Gisbert JP, Graham DY, Rokkas T. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection--the Maastricht IV/ Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61:646-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1719] [Cited by in RCA: 1587] [Article Influence: 122.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 3. | Gomollón F, Calvet X. Optimising acid inhibition treatment. Drugs. 2005;65 Suppl 1:25-33. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Boparai V, Rajagopalan J, Triadafilopoulos G. Guide to the use of proton pump inhibitors in adult patients. Drugs. 2008;68:925-947. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Calvet X, Gomollón F. What is potent acid inhibition, and how can it be achieved? Drugs. 2005;65 Suppl 1:13-23. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Rimbara E, Noguchi N, Tanabe M, Kawai T, Matsumoto Y, Sasatsu M. Susceptibilities to clarithromycin, amoxycillin and metronidazole of Helicobacter pylori isolates from the antrum and corpus in Tokyo, Japan, 1995-2001. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2005;11:307-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kobayashi I, Murakami K, Kato M, Kato S, Azuma T, Takahashi S, Uemura N, Katsuyama T, Fukuda Y, Haruma K. Changing antimicrobial susceptibility epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori strains in Japan between 2002 and 2005. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:4006-4010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Miner P, Katz PO, Chen Y, Sostek M. Gastric acid control with esomeprazole, lansoprazole, omeprazole, pantoprazole, and rabeprazole: a five-way crossover study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2616-2620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 310] [Cited by in RCA: 314] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hassan-Alin M, Andersson T, Niazi M, Röhss K. A pharmacokinetic study comparing single and repeated oral doses of 20 mg and 40 mg omeprazole and its two optical isomers, S-omeprazole (esomeprazole) and R-omeprazole, in healthy subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;60:779-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | McNicholl AG, Linares PM, Nyssen OP, Calvet X, Gisbert JP. Meta-analysis: esomeprazole or rabeprazole vs. first-generation pump inhibitors in the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:414-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Terano A, Arakawa T, Sugiyama T, Suzuki H, Joh T, Yoshikawa T, Higuchi K, Haruma K, Murakami K, Kobayashi K. Rebamipide, a gastro-protective and anti-inflammatory drug, promotes gastric ulcer healing following eradication therapy for Helicobacter pylori in a Japanese population: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:690-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gisbert JP, Pajares JM. Systematic review and meta-analysis: is 1-week proton pump inhibitor-based triple therapy sufficient to heal peptic ulcer? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:795-804. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kirchheiner J, Glatt S, Fuhr U, Klotz U, Meineke I, Seufferlein T, Brockmöller J. Relative potency of proton-pump inhibitors-comparison of effects on intragastric pH. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65:19-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | McKeage K, Blick SK, Croxtall JD, Lyseng-Williamson KA, Keating GM. Esomeprazole: a review of its use in the management of gastric acid-related diseases in adults. Drugs. 2008;68:1571-1607. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Sjøstrøm JE, Kühler T, Larsson H. Basis for the selective antibacterial activity in vitro of proton pump inhibitors against Helicobacter spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1797-1801. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Mirshahi F, Fowler G, Patel A, Shaw G. Omeprazole may exert both a bacteriostatic and a bacteriocidal effect on the growth of Helicobacter pylori (NCTC 11637) in vitro by inhibiting bacterial urease activity. J Clin Pathol. 1998;51:220-224. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Miwa H, Ohkura R, Murai T, Sato K, Nagahara A, Hirai S, Watanabe S, Sato N. Impact of rabeprazole, a new proton pump inhibitor, in triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection-comparison with omeprazole and lansoprazole. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:741-746. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Wang X, Fang JY, Lu R, Sun DF. A meta-analysis: comparison of esomeprazole and other proton pump inhibitors in eradicating Helicobacter pylori. Digestion. 2006;73:178-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Graham DY, Shiotani A. New concepts of resistance in the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infections. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;5:321-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Asaoka D, Nagahara A, Matsuhisa T, Takahashi S, Tokunaga K, Kawai T, Kawakami K, Suzuki H, Suzuki M, Nishizawa T. Trends of second-line eradication therapy for Helicobacter pylori in Japan: a multicenter study in the Tokyo metropolitan area. Helicobacter. 2013;18:468-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sasaki M, Ogasawara N, Utsumi K, Kamiya T, Kataoka H, Tanida S, Mizoshita T, Shimura T, Hirata Y, Kasugai K. The effectiveness of packed therapy with three drugs in Helicobacter pylori eradication in Japan. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 2010;32:243-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Nagahara A, Miwa H, Hojo M, Yoshizawa T, Kawabe M, Osada T, Kurosawa A, Ohkusa T, Watanabe S. Efficacy of Lansap combination therapy for eradication of H. pylori. Helicobacter. 2007;12:643-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kawai T, Kawakami K, Kataoka M, Takei K, Taira S, Itoi T, Moriyasu F, Takagi Y, Aoki T, Matsubayasiu J. The Effectiveness of Packaged Medicine in Eradication Therapy of Helicobacter pylori in Japan. J clinl biochem and nutr. 2006;38:73-76. |

| 24. | Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, Perlick DA, Friedman SJ, Meyers BS. Stigma as a barrier to recovery: Perceived stigma and patient-rated severity of illness as predictors of antidepressant drug adherence. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:1615-1620. [PubMed] |