Published online May 14, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i18.2291

Revised: November 28, 2011

Accepted: March 10, 2012

Published online: May 14, 2012

Hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm (HAP) is a very rare disease but in cases of complication, there is a very high mortality. The most common cause of HAP is iatrogenic trauma such as liver biopsy, transhepatic biliary drainage, cholecystectomy and hepatectomy. HAP may also occur with complications such as infections or inflammation associated with septic emboli. HAP has been reported rarely in patients with acute pancreatitis. As far as we are aware, there is no report of a case caused by acute idiopathic pancreatitis, particularly. We report a case of HAP caused by acute idiopathic pancreatitis which developed in a 61-year-old woman. The woman initially presented with acute pancreatitis due to unknown cause. After conservative management, her symptoms seemed to have improved. But eight days after admission, abdominal pain abruptly became worse again. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) was rechecked and it detected a new HAP that was not seen in a previous abdominal CT. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was performed because of a suspicion of hemobilia as a cause of aggravated abdominal pain. ERCP confirmed hemobilia by observing fresh blood clots at the opening of the ampulla and several filling defects in the distal common bile duct on cholangiogram. Without any particular treatment such as embolization or surgical ligation, HAP thrombosed spontaneously. Three months after discharge, abdominal CT demonstrated that HAP in the left lateral segment had disappeared.

- Citation: Yu YH, Sohn JH, Kim TY, Jeong JY, Han DS, Jeon YC, Kim MY. Hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm caused by acute idiopathic pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(18): 2291-2294

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i18/2291.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i18.2291

Hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm (HAP) is rare[1,2]. But rupture is common and occurs in 76% of patients with HAP. There are many causes of HAP, but it usually results from procedures such as liver biopsy, transhepatic biliary drainage, cholecystectomy, and hepatectomy[3]. HAP may also occur with complications such as infections or inflammation associated with septic emboli[4-7]. HAP has rarely been reported in patients with acute pancreatitis[8,9]. As far as we are aware, there is no report of a case caused by acute idiopathic pancreatitis. We report a case of HAP thought to be caused by acute pancreatitis due to unknown cause, in a 61-year-old Korean woman. HAP spontaneously thrombosed without any particular treatment and finally disappeared several months later. We also review the literature concerning HAP.

A 61-year-old Korean woman was admitted to the emergency room with right upper quadrant pain and vomiting starting 8 h before admission. She was previously well-nourished, and had no past medical history. The patient denied a history of percutaneous intervention, abdominal surgery, trauma, viral hepatitis, bleeding disorders, jaundice or blood transfusion. On admission, her blood pressure was 120/80 mmHg, pulse rate was 78/min, and body temperature was 36.8 °C. On examination, her appearance was that of acute illness and her tongue was mildly dehydrated. But she was clinically non-anemic and non-icteric. Abdominal examination revealed right upper quadrant tenderness without rebound and hepatomegaly. Rectal examination showed no melena.

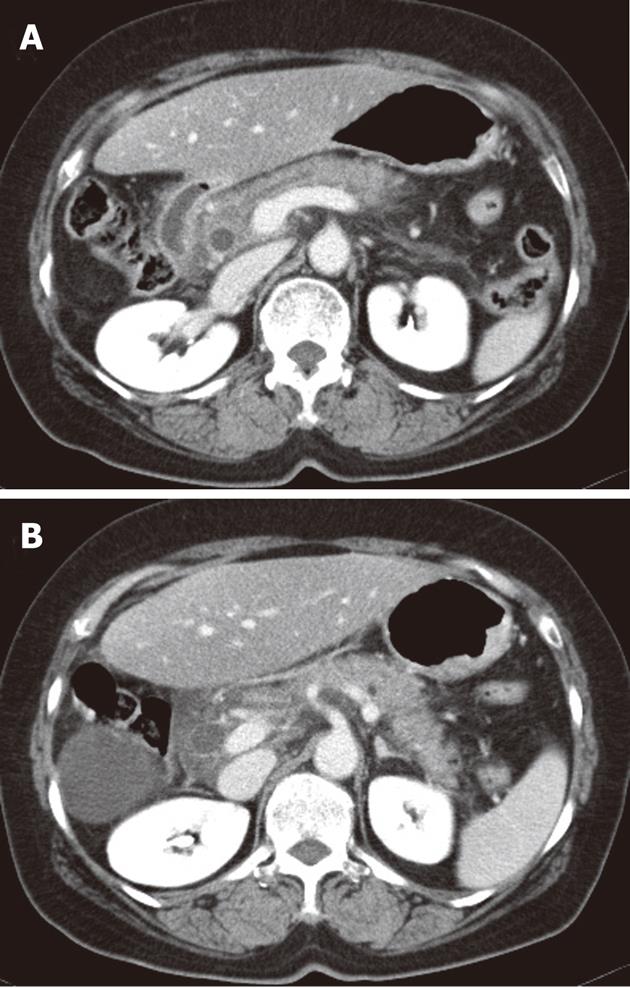

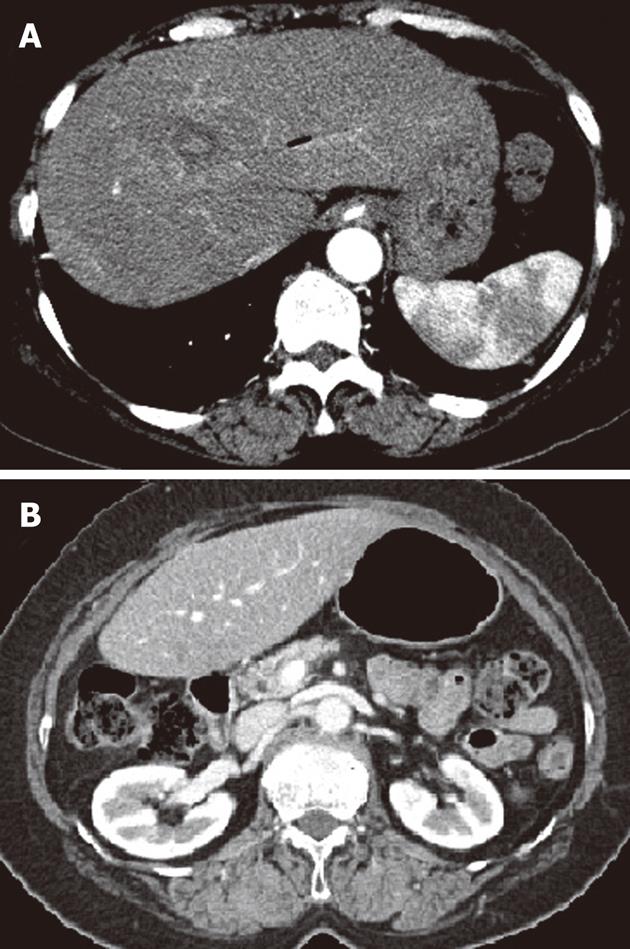

Laboratory data on admission were as follows: white blood cell count 14 900/μL with 90.5% increase in neutrophils; hemoglobin 13.4 g/dL; hematocrit 39.0%; platelet count 226 000/μL; prothrombin time 15.0 [international normalized ratio (INR) 1.27]; serum total protein 7.0 g/dL; albumin 4.4 g/dL; alkaline phosphatase 103 U/L; total bilirubin 1.0 g/dL; Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 87 U/L; aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 56 U/L; gamma-glutamyl transferase 46 U/L. Amylase (1167 U/L) and lipase (2630 U/L) were increased. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) demonstrated infiltration with swelling in an uncinate process of the pancreas head and infiltration and mural enhancement in adjacent duodenum, described as grade C according to Balthazar classification (Figure 1).

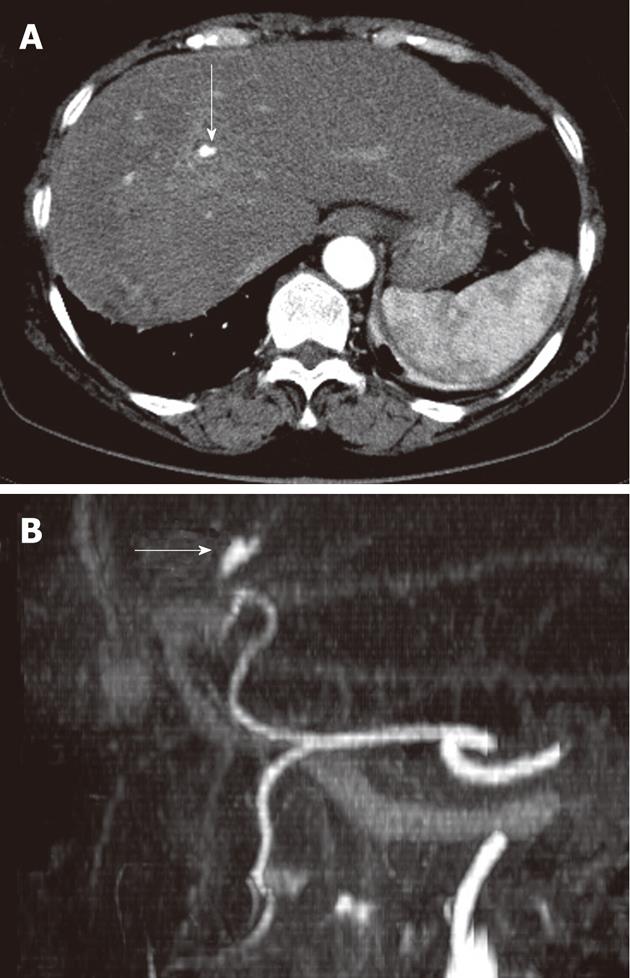

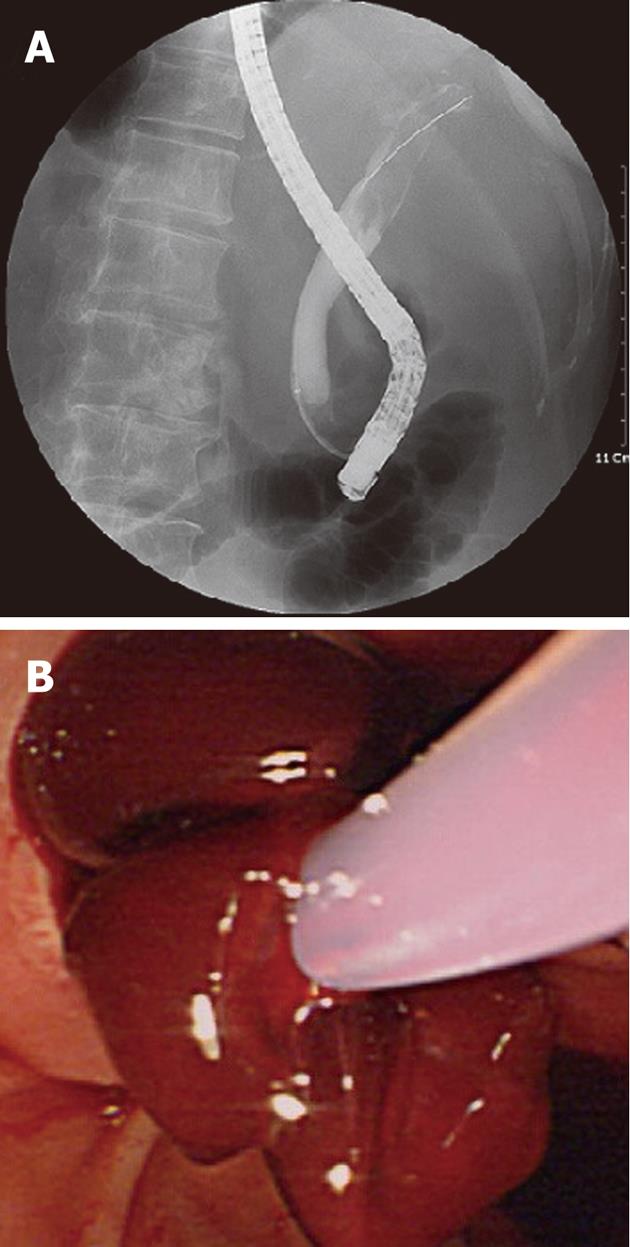

After conservative management, her symptoms were improved but eight days after admission, her abdominal pain abruptly deteriorated again. Laboratory data were as follows: hemoglobin 12.2 g/dL; hematocrit 35.7%; white blood cell count 9200/μL with 69.2% neutrophils; platelet count 118 000/μL; prothrombin time 14.1 s (INR 1.20); alkaline phosphatase 83 U/L; total bilirubin 0.6 g/dL; ALT 13 U/L; AST 22 U/L; gamma-glutamyl transferase 33 U/L. Amylase (69 U/L) and lipase (153 U/L) were within normal ranges. On a second check-up with abdominal CT, the infiltration and swelling of the pancreas head was improved and there was no stone in the biliary tract. But it showed a newly developed hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm in the left lateral segment and no evidence of acute bleeding related to it as a complication (Figure 2). We performed endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in order to find the cause of aggravated pain with suspicion of hemobilia. Several filling defects with labile and indeterminate shapes were observed on cholangiogram and, after sphincterotomy, these findings were confirmed to be caused by fresh blood clots without a stone, and blood clots were removed with a balloon catheter and basket (Figure 3). Emergent angiography was not performed due to no further acute bleeding evidence.

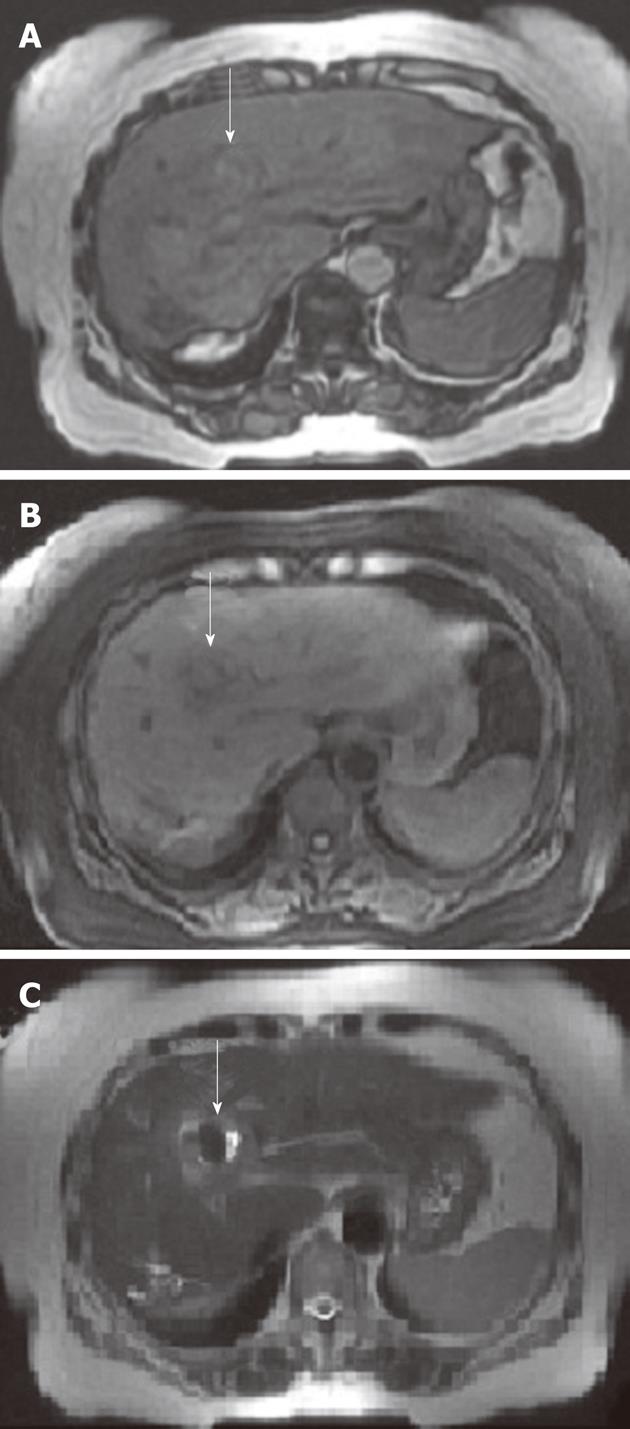

After ERCP, the patient’s pain improved and filling defects caused by blood clots of the extrahepatic duct were not observed on endoscopic nasobiliary drainage cholangiogram. Magnetic resonance imaging showed that dilatation or filling defects of the bile duct disappeared and bleeding of proximal HAP was replaced by thrombus formation (Figure 4). Two days later, angiography revealed no visible contrast leakage and definite HAP. Her symptoms resolved rapidly, and she was discharged on the 16th day after clot removal.

Three months after discharge, abdominal CT demonstrated that minimal bile duct dilatation was noted but HAP in the left lateral segment had disappeared and pancreatitis improved (Figure 5).

HAP is mainly caused by acute or chronic artery injuries such as blunt or penetrating injuries and interventional radiological procedures[10]. A minority of their formation may occur as a result of bile duct damage usually associated with stone impaction or procedure-related infection[4-6]. Unlike these reports, this case suggests that HAP occurred due to no invasive procedure and infection but acute pancreatitis. In this case, acute pancreatitis due to unknown cause may have eroded the arterial wall and led to pseudoaneurysm formation and then HAP’s rupture causing hemobilia. The mechanism of pseudo-aneurysm formation in pancreatitis is thought to be due to autodigestion of pancreatic enzymes. Among HAP caused by pancreatitis, most cases have been reported to be due to chronic pancreatitis, but HAP caused by acute pancreatitis has only rarely been reported[11]. Furthermore, among reports of HAP due to acute pancreatitis, acute idiopathic pancreatitis causing HAP has not been reported so far.

In this case, it can be presumed that a rupture of preexisting HAP was not detected on initial abdominal CT imaging, resulting in hemobilia and eventually, acute pancreatitis was complicated by hemobilia. However, considering the fact the patient had normal levels of hemoglobin and no bile duct dilatation or filling defects when visiting hospital and the clinical course worsened (e.g., pain) despite the improvement of acute pancreatitis during the treatment, this possibility is very low. She was hospitalized for 8 d without any evidence of this procedure, and hemobilia-induced abdominal pain developed without aggravation of acute pancreatitis. This makes the scenario of pancreatitis-induced HAP more reasonable.

HAP is a rare and potentially fatal disease if it ruptures. In most cases, conservative management is not recommended due to the high rupture rate. Treatment comprises reconstructive surgery, or ligation depending on the size of the lesion and its location in the past. Today, the treatment of choice is selective transcatheter embolization[10,12,13]. However, in very limited cases, which means, unless HAP is not at risk of immediate rupture because of progressively enlarging size or instability, it can be managed by closed medical observation and imaging follow-up with appropriate treatment of the associated infection[14]. In this case, there was only conservative management of acute pancreatitis which is thought to be a cause of HAP. But we could confirm that HAP spontaneously thrombosed without any particular treatment at the image study. Three months after discharge, abdominal CT demonstrated that HAP in the left lateral segment had disappeared.

In summary, we report a rare case of a 61-year-old Korean woman who had HAP caused by acute idiopathic pancreatitis. In this case, HAP spontaneously thrombosed and then disappeared after recovery of acute pancreatitis. This case alerts clinicians that acute pancreatitis can be considered as a potential cause of HAP.

Peer reviewer: Luis Grande, Professor, Department of Surgery, Hospital del Mar, Passeig Marítim 25-29, 08003 Barcelona, Spain

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor O’Neill M E- Editor Xiong L

| 2. | Harlaftis NN, Akin JT. Hemobilia from ruptured hepatic artery aneurysm. Report of a case and review of the literature. Am J Surg. 1977;133:229-232. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Tessier DJ, Fowl RJ, Stone WM, McKusick MA, Abbas MA, Sarr MG, Nagorney DM, Cherry KJ, Gloviczki P. Iatrogenic hepatic artery pseudoaneurysms: an uncommon complication after hepatic, biliary, and pancreatic procedures. Ann Vasc Surg. 2003;17:663-669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Van Os EC, Petersen BT. Pancreatitis secondary to percutaneous liver biopsy-associated hemobilia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:577-580. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Cacho G, Abreu L, Calleja JL, Prados E, Albillos A, Chantar C, Perez Picouto JL, Escartín P. Arterioportal fistula and hemobilia with associated acute cholecystitis: a complication of percutaneous liver biopsy. Hepatogastroenterology. 1996;43:1020-1023. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Worobetz LJ, Passi RB, Sullivan SN. Hemobilia after percutaneous liver biopsy: role of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and sphincterotomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1983;78:182-184. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Siablis D, Papathanassiou ZG, Karnabatidis D, Christeas N, Vagianos C. Hemobilia secondary to hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm: an unusual complication of bile leakage in a patient with a history of a resected IIIb Klatskin tumor. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:5229-5231. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Sethi H, Peddu P, Prachalias A, Kane P, Karani J, Rela M, Heaton N. Selective embolization for bleeding visceral artery pseudoaneurysms in patients with pancreatitis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2010;9:634-638. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Mortelé KJ, Mergo PJ, Taylor HM, Wiesner W, Cantisani V, Ernst MD, Kalantari BN, Ros PR. Peripancreatic vascular abnormalities complicating acute pancreatitis: contrast-enhanced helical CT findings. Eur J Radiol. 2004;52:67-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Finley DS, Hinojosa MW, Paya M, Imagawa DK. Hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm: a report of seven cases and a review of the literature. Surg Today. 2005;35:543-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Walton JM, Abraham RJ, Perey BJ, MacGregor JH, Campbell DR. Hepatic artery pseudoaneurysms in acute pancreatitis. Can J Surg. 1991;34:377-380. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Ahn J, Trost DW, Mitty HA, Sos TA. Pseudoaneurysm formation after catheter dissection of the common hepatic artery: report of two cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:696-699. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Nakajima M, Hoshino H, Hayashi E, Nagano K, Nishimura D, Katada N, Sano H, Okamoto K, Kato K. Pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery associated with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:750-754. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Ruess L, Sivit CJ, Eichelberger MR, Gotschall CS, Taylor GA. Blunt abdominal trauma in children: impact of CT on operative and nonoperative management. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:1011-1014. [PubMed] |