Published online Jun 1, 2004. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i11.1547

Revised: January 4, 2004

Accepted: January 29, 2004

Published online: June 1, 2004

AIM: To determine the influence of gender on the clinicopathologic characteristics and survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

METHODS: A retrospective analysis of medical records was performed in 299 patients with HCC and their clinicopathologic features and survival were compared in relation to gender.

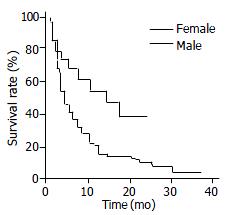

RESULTS: There were 260 male (87%) and 39 female patients (13%), with a male-to-female ratio of 6.7:1. Female patients had lower mean serum bilirubin levels (P = 0.03), lower proportion of alcohol abuse (P = 0.002), smaller mean tumor size (P = 0.02), more frequent nodular type but less frequent massive and diffuse types of HCC (P = 0.01), were less advanced in Okuda’s staging (P = 0.04), and less frequently associated with venous invasion (P = 0.03). The median survivals in females (14 mo) were significantly longer than that of male patients (4 mo) (P = 0.004, log-rank test). Multivariate analysis demonstrated that high serum alpha-fetoprotein levels, venous invasion, extrahepatic metastasis and lack of therapy were independent factors related to unfavorable prognosis. However, gender did not constitute a predictive variable associated with patient survival.

CONCLUSION: Female patients tend to have higher survival rates than males. These differences were probably due to more favorable pathologic features of HCC at initial diagnosis and greater likelihood to undergo curative therapy in female patients.

- Citation: Tangkijvanich P, Mahachai V, Suwangool P, Poovorawan Y. Gender difference in clinicopathologic features and survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2004; 10(11): 1547-1550

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v10/i11/1547.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v10.i11.1547

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common cancers worldwide with a particularly high incidence in areas where chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) are common[1,2]. These regions include sub-Saharan Africa, Far East and Southeast Asia where the annual rate is more than 30 cases per 100000 persons. In contrast, in low-incidence areas such as Europe and North America, the annual rate is less than 5 cases per 100000 persons[3]. In Thailand, where chronic HBV is endemic, it is estimated that more than 10000 new cases of HCC are diagnosed each year. Indeed, HCC represents the most common malignancy in Thai males and the third most common malignancy in females[4].

Previously, we demonstrated that HCC in Thailand had an indisputable male predominance, with a male-to-female ratio of approximately 6:1[5]. In fact, HCC is notably more prevalent in males worldwide, with reported male-to-female ratios ranging from 2:1 to 8:1 in most series. Until now, however, only a few studies have specifically compared the clinicopathologic characteristics of patients with HCC in relation to gender. In addition, the contribution of sex difference to patient survival and prognosis is controversial[6-13]. The aim of the present study was, therefore, to determine the influence of gender on clinicopathologic features and patient survival. In this respect, we analyzed the medical records on individuals in whom HCC was diagnosed during a four-year period at King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital (Bangkok, Thailand).

A total of 299 patients with HCC who were admitted to King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital between January 1996 and September 1999 were retrospectively analyzed and included in this study. All patients were diagnosed based on liver tumor characteristics detected by ultrasound/CT scan and confirmed by histology or serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels above 400 IU/mL. Of those, there were 260 male (87%) and 39 female patients (13%), making a male-to-female ratio of 6.7:1. We compared the difference and the clinicopathologic features, including age, biochemical liver function test, presence or absence of associated cirrhosis, etiologic factors predisposing towards HCC (alcohol abuse, hepatitis B or C), degree of tumor differentiation, gross pathology of tumor, tumor size, presence of vascular invasion, stage of HCC according to Okuda’s criteria, evidence of distant metastasis and modalities of therapy of HCC. In addition, the patients’ survival time for each group was also calculated, starting with the time of cancer diagnosis (including any incidence of perioperative mortality).

Gross pathology, tumor size, and localization of HCC as well as presence of portal or hepatic venous involvement, were obtained by abdominal ultrasound or computerized tomography (CT). In this study, the gross pathologic types of HCC were categorized according to Trevisani et al[14] as follows:nodular, multinodular, infiltrative, diffuse (the mass was not clearly defined and the boundary was indistinct) or massive type (a huge mass > 10 cm with the boundary not well defined).

Biochemical liver function tests were determined by automated chemical analyzer (Hitachi 911) at the central laboratory of Chulalongkorn Hospital. The normal levels obtained with healthy adults are within the range of 0-38 IU/L for serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and 98-279 IU/L for serum alkaline phosphatase (AP). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) were used for the detection of HBsAg (Auszyme II, Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL), anti-HCV (ELISA II; Ortho Diagnostic Systems, Chiron Corp., Emeryville, CA) and AFP (Cobus®Core, Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland).

Data were presented as percentage, mean and standard deviation. The Chi-square test and unpaired t test were used to assess the statistical significance of the difference between groups as appropriate. Survival curves were established using the Kaplan-Meier method and differences between curves were demonstrated using the log-rank test. The Cox regression analysis was performed to identify which independent factors have a significant influence on the overall survival. P values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

As shown in Table 1, the mean age of female patients (56.4 ± 15.2 years) was slightly higher, but not significantly different from that of male patients (52.6 ± 13.2 years). There was a significantly lower proportion of heavy alcohol consumption among females than males (P = 0.002). However, there were no significant differences in positive rates of serum HBsAg and anti-HCV, nor in the frequency of associated liver cirrhosis between the two groups. Similarly, no significant differences between groups were observed regarding mean serum AFP levels and biochemical abnormalities, with the exception that female patients had significantly lower serum bilirubin levels than male patients (P = 0.03).

| Characteristics | Female (n = 39) | Male (n = 260) | P |

| Age (yr) | 56.4 ± 15.2 | 52.6 ± 13.2 | NS |

| Underlying cirrhosis (+:-) | 36:3 | 251:9 | NS |

| Viral hepatitis marker | |||

| HBsAg (+:-) | 18:21 | 147:113 | NS |

| Anti-HCV (+:-) | 5:34 | 23:237 | NS |

| Heavy alcohol consumption (+:-) | 3:36 | 83:177 | 0.002 |

| Mean AFP (IU/mL) | 48435.4 ± 105231.6 | 40221.9 ± 89147.9 | NS |

| Biochemical liver function tests | |||

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.5 ± 1.2 | 3.1 ± 2.3 | 0.03 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 451.6 ± 277.3 | 529.3 ± 375.0 | NS |

| AST (IU/L) | 128.4 ± 133.2 | 154.3 ± 135.2 | NS |

| ALT (IU/L) | 62.7 ± 52.6 | 87.6 ± 97.5 | NS |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.6 ± 0.7 | 3.4 ± 0.7 | NS |

| Prothrombin time (sec) | 14.5 ± 2.8 | 15.1 ± 9.3 | NS |

Table 2 demonstrates the clinicopathologic data of the patients at the time of the diagnosis of HCC. Female patients in this study tended to have less aggressive tumor characteristics than male patients. For instance, the mean tumor size in females (8.6 cm) was significantly smaller than that of male patients (11.6 cm) (P = 0.02). In addition, the nodular type of HCC appeared to be more frequently found among female patients, whereas the massive and diffuse types were more common among males (P = 0.01). Furthermore, the tumors in the female group tended to be of a less advanced stage according to Okuda’s criteria (P = 0.04) and less frequently associated with portal or hepatic vein invasion (P = 0.03). Nonetheless, no significant differences between groups were observed as to the degree of tumor differentiation, the prevalence of extrahepatic metastasis or ruptured HCC.

| Characteristics | Female (n = 39) | Male (n = 260) | P |

| Mean tumor size (cm) | 8.1 ± 3.9 | 11.6 ± 4.5 | 0.02 |

| Tumor size | |||

| ≤5 cm:> 5 cm | 9:30 | 30:230 | 0.04 |

| Gross appearance of HCC | |||

| Nodular:Multinodular:Massive:Diffuse | 12:10:14:3 | 30:52:115:63 | 0.01 |

| Tumor cell differentiation | |||

| Well:Moderately:Poorly | 3:5:4 | 11:66:32 | NS |

| Okuda’ s staging (I:II:III) | 13:23:3 | 43:180:37 | 0.04 |

| Portal or hepatic vein invasion (+:-) | 6:33 | 84:176 | 0.03 |

| Extrahepatic metastasis (+:-) | 5:34 | 37:223 | NS |

| Ruptured HCC (+:-) | 1:38 | 29:231 | NS |

| Therapy for HCC (+:-) | 22:17 | 105:155 | NS |

| Modality of therapy | |||

| Surgical resection (+:-) | 9:30 | 27:233 | 0.02 |

| Chemoembolization (+:-) | 13:26 | 43:217 | 0.01 |

| Systemic chemotherapy (+:-) | 0:39 | 31:229 | 0.02 |

Likewise, there was no statistically significant difference between groups in terms of the number of patients treated with specific therapeutic modalities. However, female patients were more likely than male patients to undergo surgical resection, which included segmental and lobar resection, or treated with transcatherter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) (P = 0.02 and 0.01, respectively). In contrast, a significantly higher proportion of male patients were treated with systemic chemotherapy than females (P = 0.02).

The median survival time of all patients in this study, regardless of their gender, was 5 mo. The Kaplan-Meier survival curves demonstrated that the overall median survival for female and male patients were 14 and 4 mo, respectively (P = 0.004, using log-rank test) (Figure 1). For patients who were treated with any specific therapeutic modality, the median survival for the female and male group were 17 and 7 mo, respectively (P = 0.025). In the untreated cases, the median survival of the female group was longer than that of the male group (9 and 3 mo, respectively), however, this difference did not achieve statistical significance (P = 0.24).

Univariate analysis of the main variables was performed to determine significant risk factors associated with the overall survival. In addition to male sex, serum AFP levels > 400 IU/mL, Okuda’s stage II and III HCC, massive or diffuse types of tumors, tumor mass size over 5 cm in diameter, venous invasion and extrahepatic metastasis, and an unfavorable prognosis were observed in patients who did not receive any specific therapy for HCC. Stepwise Cox regression multivariate analysis revealed that high serum AFP levels, venous invasion, extrahepatic metastasis and absence of specific therapy were significantly and independently predictive for unfavorable prognosis (Table 3). Nonetheless, gender was not selected in the final analysis as an independent predictor of survival.

Various types of cancer occur more frequently in male than in female patients. Such is also the case with HCC. In fact, marked male predominance in HCC incidence is observed in both high- and low-risk areas, regardless of ethnic and geographic diversity[15]. Despite this, the exact reasons for sex difference in the incidence of HCC are unclear. It has been reported that DNA synthetic activities are higher in male than in female cirrhotics and this might be one of the possible explanations for the gender discrepancy in HCC[16]. However, in patients who had already developed HCC, a significant difference in tumor cellular proliferation between male and female patients was not detected[11]. It has also been suggested that the effect of sex hormones may contribute, at least in part, to the greater incidence of HCC observed in male patients. Although the mechanism remains to be elucidated, studies from animal models has implicated that the hormonal effect may be related to testosterone’s ability in enhancing transforming growth factor (TGF) alpha related hepatocarcinogenesis and hepatocyte proliferation[17].

Beside this, other possible factors contributing to the male predominance in HCC include the association with HBV infection, the higher proportion of male cirrhotics and differences in life-style habits, such as heavy alcohol consumption and smoking[6,10]. However, in this study, no significant difference was found between groups in the prevalence of associated cirrhosis. Likewise, although HBsAg carriers were slightly more common in males, this discrepancy did not reach statistical significance. Notably, this was also the case with the prevalence of chronic HCV infection in our study. In contrast, the prevalence of heavy alcohol consumption was significantly different, being higher in male than in female patients. Indeed, alcoholic cirrhosis has long been recognized as a risk factor for developing HCC, although its role in direct hepatocarcinogenesis is uncertain[18]. Nonetheless, it is reasonable to speculate that chronic alcohol abuse might accelerate cancer development in some cases with HBV- or HCV-associated cirrhosis and this may be partially responsible for the male preponderance of HCC in our series.

In addition, to confirm the marked male predominance, our study has demonstrated that male patients with HCC had a less favorable prognosis than females after initial diagnosis. Specifically, better survival in females was observed in those who had undergone surgical resection or treated with TACE. For untreated cases, the influence of gender on prognosis seemed to be limited since significant difference in survival between groups was not achieved, although there was a trend for females to survive longer. These results were consistent with previous reports in which a better prognosis was observed in females following hepatic resection[9-13]. For instance, according to the study in Japan by Nagasue et al[9], significantly better survival rates were found in females after 4 years of hepatic surgery. A previous report on Chinese patients by Cong et al[10] also demonstrated that the survival rates after surgery were approximately 50% and 25% in females and males, respectively. Likewise, a study in Hong Kong by Ng et al[11], indicated that females had a lower incidence of tumor recurrence following the surgical operations, with a median disease free survival of 19.5 mocompared with 4.5 mo for males. Recently, Lee et al[12] reported that female cirrhotics with HCC had 5-year disease survival rates after hepatic resection, which was higher than males (approximately 65% and 30%, respectively). Conversely, such favorable prognosis in females was not consistently observed among patients with inoperable tumors[6-8].

Thus, it could be speculated that the prognosis of HCC is not directly influenced by the sex of the patients. This is confirmed in our study that gender was not selected as an independent predictor of survival from the multivariate analysis. In fact, a better prognosis in females was probably attributed to a less advanced stage of HCC at initial diagnosis and, as a result, a higher proportion of cases was likely to undergo surgical resection or treated with TACE. In this study, for example, approximately 25% and 35% of female patients were treated with hepatic resection or TACE, respectively, while only approximately 10% and 15% of males were treated with such modalities. It has been generally recognized that hepatic resection is one of the most effective therapeutic modalities offering a hope of cure for patients with HCC[19,20]. Moreover, a non-surgical approach such as TACE appears to be beneficial in prolonging survival for some patients with unresectable tumors[21-22].

In addition to therapeutic factors, some pathobiologic features indicative of tumor invasiveness, such as venous involvement, appear to be significant factors influencing the survival of HCC[23]. It has also been demonstrated that the presence of venous invasion is associated with a higher intrahepatic recurrence rate after the resection of the tumor[24]. Although HCC is characterized by its propensity for vascular invasion, it is interesting that female patients with HCC had a much lower prevalence of venous involvement than males. It seems, therefore, that this is probably one of the main factors contributing to different survival rates between the two sexes in our study. Similarly, yet to be addressed, are the effects of other tumor pathologic features, such as tumor encapsulation during the disease-free period after surgical resection of HCC[25]. Previous data have demonstrated that females have a significantly higher prevalence of tumor encapsulation than males (80% and 45%, respectively). Furthermore, the tumors in females were frequently less invasive in terms of lower prevalence of tumor microsatellites and positive histological margin[11].

In conclusion, our data indicated that female patients with HCC had certain clinicopathologic features different from those in male patients. Moreover, females with HCC appeared to have better survival rates than males. This better prognosis in females was related to more favorable tumor characteristics such as a lower prevalence of hepatic or portal venous invasion and less advanced stages at initial diagnosis. As a result, female patients were more likely than male patients to undergo hepatic resection or to be treated with TACE.

We would like to express our gratitude to the Thailand Research Fund, Senior Research Scholar and the Molecular Biology Project, Chulalongkorn University for supporting the study. We also would like to thank Ms. Pisanee Saiklin for editing the manuscript.

Edited by Ma JY Proofread by Xu FM

| 1. | Chen CJ, Yu MW, Liaw YF. Epidemiological characteristics and risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;12:S294-S308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 341] [Cited by in RCA: 338] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tang ZY. Hepatocellular carcinoma--cause, treatment and metastasis. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:445-454. [PubMed] |

| 3. | McGlynn KA, Tsao L, Hsing AW, Devesa SS, Fraumeni JF. International trends and patterns of primary liver cancer. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:290-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in RCA: 240] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Srivatanakul P. Epidemiology of Liver Cancer in Thailand. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2001;2:117-121. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Tangkijvanich P, Hirsch P, Theamboonlers A, Nuchprayoon I, Poovorawan Y. Association of hepatitis viruses with hepatocellular carcinoma in Thailand. J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:227-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lai CL, Gregory PB, Wu PC, Lok AS, Wong KP, Ng MM. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Chinese males and females. Possible causes for the male predominance. Cancer. 1987;60:1107-1110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Calvet X, Bruix J, Ginés P, Bru C, Solé M, Vilana R, Rodés J. Prognostic factors of hepatocellular carcinoma in the west:a multivariate analysis in 206 patients. Hepatology. 1990;12:753-760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Falkson G, Cnaan A, Schutt AJ, Ryan LM, Falkson HC. Prognostic factors for survival in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1988;48:7314-7318. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Nagasue N, Galizia G, Yukaya H, Kohno H, Chang YC, Hayashi T, Nakamura T. Better survival in women than in men after radical resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 1989;36:379-383. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Cong WM, Wu MC, Zhang XH, Chen H, Yuan JY. Primary hepatocellular carcinoma in women of mainland China. A clinicopathologic analysis of 104 patients. Cancer. 1993;71:2941-2945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ng IO, Ng MM, Lai EC, Fan ST. Better survival in female patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Possible causes from a pathologic approach. Cancer. 1995;75:18-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lee CC, Chau GY, Lui WY, Tsay SH, King KL, Loong CC, Hshia CY, Wu CW. Better post-resectional survival in female cirrhotic patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:446-449. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Dohmen K, Shigematsu H, Irie K, Ishibashi H. Longer survival in female than male with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:267-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Trevisani F, Caraceni P, Bernardi M, D'Intino PE, Arienti V, Amorati P, Stefanini GF, Grazi G, Mazziotti A, Fornalè L. Gross pathologic types of hepatocellular carcinoma in Italian patients. Relationship with demographic, environmental, and clinical factors. Cancer. 1993;72:1557-1563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma:an epidemiologic view. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35:S72-S78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 451] [Cited by in RCA: 467] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tarao K, Ohkawa S, Shimizu A, Harada M, Nakamura Y, Ito Y, Tamai S, Hoshino H, Okamoto N, Iimori K. The male preponderance in incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients may depend on the higher DNA synthetic activity of cirrhotic tissue in men. Cancer. 1993;72:369-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Matsumoto T, Takagi H, Mori M. Androgen dependency of hepatocarcinogenesis in TGFalpha transgenic mice. Liver. 2000;20:228-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Adami HO, Hsing AW, McLaughlin JK, Trichopoulos D, Hacker D, Ekbom A, Persson I. Alcoholism and liver cirrhosis in the etiology of primary liver cancer. Int J Cancer. 1992;51:898-902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Befeler AS, Di Bisceglie AM. Hepatocellular carcinoma:diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1609-1619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 395] [Cited by in RCA: 417] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Qian J, Feng GS, Vogl T. Combined interventional therapies of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:1885-1891. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Pawarode A, Tangkijvanich P, Voravud N. Outcomes of primary hepatocellular carcinoma treatment:an 8-year experience with 368 patients in Thailand. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:860-864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lo CM, Ngan H, Tso WK, Liu CL, Lam CM, Poon RT, Fan ST, Wong J. Randomized controlled trial of transarterial lipiodol chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2002;35:1164-1171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1904] [Cited by in RCA: 1986] [Article Influence: 86.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ringe B, Pichlmayr R, Wittekind C, Tusch G. Surgical treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma:experience with liver resection and transplantation in 198 patients. World J Surg. 1991;15:270-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 424] [Cited by in RCA: 419] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Nagasue N, Uchida M, Makino Y, Takemoto Y, Yamanoi A, Hayashi T, Chang YC, Kohno H, Nakamura T, Yukaya H. Incidence and factors associated with intrahepatic recurrence following resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:488-494. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Ng IO, Lai EC, Ng MM, Fan ST. Tumor encapsulation in hepatocellular carcinoma. A pathologic study of 189 cases. Cancer. 1992;70:45-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |