Published online Feb 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i6.1446

Peer-review started: October 17, 2020

First decision: December 8, 2020

Revised: December 23, 2020

Accepted: January 6, 2021

Article in press: January 6, 2021

Published online: February 26, 2021

Processing time: 111 Days and 23.4 Hours

Oral lichen planus (OLP) is a chronic inflammatory disorder, and it can affect normal oral function. The conventional treatments for OLP are not always effective, and relapse easily occurs. Therefore, treatment of OLP is difficult and challenging. In this study, we evaluated over a long period the clinical efficacy of surgical excision and acellular dermal matrix (ADM) grafting in patients with refractory OLP.

Eleven patients with refractory OLP underwent a standardized protocol of surgical excision and ADM grafting. The condition of the area of the grafted wound, the intraoperative maximum mouth opening, pain, and clinical healing were assessed at postoperative follow-up visits. All patients had a flat surgical area with similar mucosal tissue coverage and local scar formation. Patients had no irritation and pain in their mucous membranes when eating acidic and spicy food. All patients’ mouth openings returned to normal within 2-6 mo after surgery. During follow-up, none of the patients had recurrence of OLP after surgery. The longest follow-up was 11 yr and the shortest was 6 mo, and none of the patients relapsed during follow-up.

Surgical excision and ADM grafting could be an effective method to treat refractory OLP.

Core Tip: We report 11 patients with oral lichen planus who were treated with medication but with poor efficacy, and relapse easily occurred. In order to relieve pain and avoid malignant transformation, we removed the lesions surgically and repaired the postoperative mucosal defect with acellular dermal matrix. The postoperative effect was good, the pain disappeared, and the degree of mouth opening returned to normal. No immunological rejection or recurrence of oral lichen planus was seen during follow-up of 6 mo to 11 yr.

- Citation: Fu ZZ, Chen LQ, Xu YX, Yue J, Ding Q, Xiao WL. Treatment of oral lichen planus by surgical excision and acellular dermal matrix grafting: Eleven case reports and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(6): 1446-1454

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i6/1446.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i6.1446

Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory disease. It usually involves skin, nails, scalp, and oral and genital mucous membranes[1]. Oral lichen planus (OLP) is found in the oral mucosa, tongue, and gingiva. The oral mucosa is often the only site of damage. It can present as symmetrical and bilateral[1]. The prevalence of OLP is 0.5%-2.6% of the population[2]. It can occur at any age but mainly affects middle-aged and elderly women.

The clinical presentation of OLP involves a range of asymptomatic to symptomatic lesions. Based on the clinical presentation, OLP can be divided into six types: Reticular, popular, plaque, erosive, atrophic, and ulcerative[3]. Asymptomatic patients have no need for any intervention or treatment, but patients should be checked regularly with a follow-up every 4-6 mo. Patients should come to the hospital for examination and treatment immediately when any symptoms occur[4]. Many patients have obvious symptoms, such as oral discomfort, sensitivity to spicy and acidic foods, a painful and/or burning sensation of the oral mucosa, ulcer, and bleeding. Sometimes, oral pain can limit oral function, such as mouth opening, eating, speaking, and swallowing[5].

OLP is associated with the immune system, but its exact etiology is unknown. It is probably a multifactorial process with various triggers, such as mechanical, psychological, and electrochemical factors. Overwork, stress, anxiety, and other factors play a significant role in the initiation of OLP. The World Health Organization classified OLP as a potentially premalignant lesion, and it can convert into squamous cell carcinoma[6]. Therefore, the treatment of OLP is gaining more attention. OLP is often not fully curable and is prone to relapse making its treatment challenging. The conventional conservative treatments for OLP include conservative drug therapy (steroids, retinoids, immunosuppressants, and herbal remedies) and some novel therapies (cryosurgery and photodynamic therapy).

Corticosteroids are the drugs of choice for treatment of OLP[4]. Topical treatment is generally preferred, but systemic agents are indicated if lesions are disseminated and when topical therapies are not effective. A frequent topical treatment is 0.1% triamcinolone acetonide ointment three times daily[7]. The dose of systemic steroids must be individualized according to the severity of the lesion, the patient’s weight, and response to treatment. For example, with a short course of corticosteroids such as prednisolone, the drug should be administered at 0.5-1.0 mg/kg of the patient’s body weight per day[8]. However, systemic or topical application of corticosteroids does not always work well, and adverse effects include oral candidiasis, smarting sensation in the mouth, gingival tenderness, insomnia, mood swings, fatigue, water retention, and adrenal suppression[9].

Topical retinoids were recommended as a second-line treatment for OLP by the consensus of the World Workshop in Oral Medicine IV[10]. Topical retinoids have some adverse effects, and they can induce high serum levels of triglycerides and liver enzymes[11]. The anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory activities of immunomodulators have led to consideration of their use in OLP[12]. From the trials comparing cyclosporine with topical steroids, we found that cyclosporine did not provide additional benefit to steroids, and results were comparable[13]. However, because of its high cost and adverse effect of burning sensation, it is not considered superior to topical steroids[11]. Long-term levamisole can lead to liver damage, agranulocytosis, and encephalitis and is not suitable for long-term use[10].

Tacrolimus is effective in treating lichen planus. The most common side effects of topical tacrolimus are transient burning, pruritus at the site of application, and ease of relapse[10]. Curcumin is a Chinese herbal extract. It demonstrates antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and anticarcinogenic activities[14]. Curcumin has different effects on various oral diseases. Kia et al[15] found that curcumin can reduce the size of lesions and pain. However, the clinical use of curcumin has some shortcomings including its low solubility, high rate of metabolism, and low bioavailability[16].

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) can be used to coordinate the whole body and regulate the functions of qi and blood. According to TCM, OLP is mainly caused by anxiety, dampness, heating and fire, inflammation, Yin blood deficiency, or liver and kidney Yin deficiency. Therefore, treatment of this disease should be based on the principles of harmonizing liver and spleen, regulating qi-flowing for strengthening spleen, dispersing stagnated liver qi for relieving qi stagnation, and clearing heat-fire. As widely known, TCM is reported to be safe and beneficial[17]. However, TCM is not as effective as corticosteroids, and its effects are relatively slow. Therefore, it cannot be used as a corticosteroid replacement and can only be an adjuvant drug[18].

Photodynamic therapy is selectively toxic to damaged tissue, including inflammation and cancer, causing cell damage and membrane lysis, while it is harmless to healthy tissue[19]. However, it has some adverse effects, including burning sensation and swelling, and it is not as effective as corticosteroids[20]. Therefore, photodynamic therapy is used as an adjunctive therapy. Cryosurgery and laser surgery of the oral lesions have the main drawback in that the entire lesion cannot be histologically examined[21].

Given the long treatment cycle of the above treatment methods, it is not easy to completely eradicate OLP and it is easy to relapse. Therefore, surgical treatment is an alternative. Some researchers have tried to use surgical excision of OLP using mucosal advancement flaps[22], skin grafts[23], or platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) membranes[24] to repair the defect after surgical resection. We performed surgical excision and repaired mucosal defects with acellular dermal matrix (ADM) and achieved a satisfactory outcome.

Eleven patients came to the Stomatology Department of our hospital for treatment because of burning sensation in the mouth and limited opening of the mouth for several years (the specific duration is shown in Table 1).

| Patient | Sex | Age in yr | Duration of LP in yr | Systemic disease | Previous treatment | Previous relapse time in yr |

| 1 | F | 56 | 4 | Hypertension | CT | 2 |

| 2 | F | 48 | 3 | Hypertension | CT, tretinoin | 1 |

| 3 | F | 60 | 5 | Hypertension | CT | 2 |

| 4 | F | 59 | 4 | Chronic hepatitis | CT | 1.5 |

| 5 | F | 55 | 4.5 | Diabetes mellitus | CT | 1 |

| 6 | F | 40 | 2.5 | Hypertension | CT, tretinoin | 1 |

| 7 | F | 65 | 4 | Hypertension; diabetes mellitus | CT, ciclosporin | 1.2 |

| 8 | M | 59 | 3 | Hypertension; chronic hepatitis | CT, tretinoin | 1 |

| 9 | M | 60 | 3.5 | Diabetes mellitus | CT, ciclosporin | 1.5 |

| 10 | M | 65 | 5 | Hypertension; chronic hepatitis | CT, tretinoin | 2.5 |

| 11 | M | 56 | 3.5 | Hypertension | CT | 1 |

The patients had mucosal pain and limited mouth opening for several years before admission. All had received local corticosteroids (0.1% triamcinolone ointment three times daily). Four patients were treated with 0.1% tretinoin ointment three times daily. A mouth rinse with 5 mL 0.1% cyclosporin gargle three times daily was used in three patients (Table 1). However, the efficacy was poor, and relapse was easy.

All had a history of systemic disease (Table 1). Among them, eight suffered from hypertension, four from diabetes mellitus, and three from chronic hepatitis; all of which were well controlled with nifedipine, metformin, and entecavir, respectively.

None of the patients had a history of drug allergies or genetic diseases.

The patients’ vital signs were normal. Oral examination revealed white lesions within the area of erosion, congestion, ulcer, conscious pain, pain stimulation, easy bleeding, and white bands with radial texture around the lesion (Figure 1). All lesions occurred on the buccal side. Two cases were bilateral and nine were unilateral.

All patients had different degrees of elevated white blood cells. Liver and renal functions as well as thyroid function were normal (except for four patients with chronic hepatitis). The levels of aspartate aminotransferase in Patients 4, 8, 10, and 11 were 45, 51, 42, and 45 U/L, respectively. The normal range is 0-40 U/L. The fasting blood glucose levels of patients 5, 7, and 9 were 6.89, 7.60, and 7.30 mmol/L, respectively.

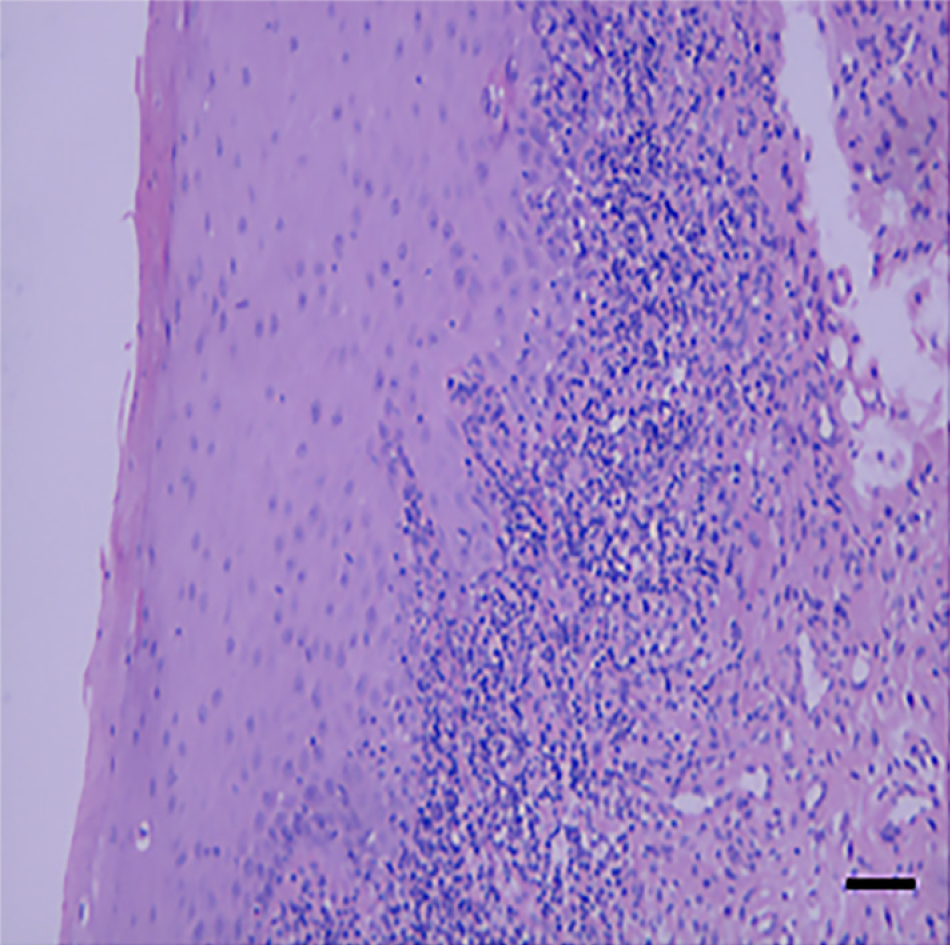

The mucous membrane presented with chronic inflammation. The squamous epithelium was highly hyperplastic and hyperkeratinized with local mild dysplasia. Hydropic degeneration of the basal epithelial cells, unclear basement membrane structure, and prominent infiltration of band-like subepithelial lymphocytes and plasma cells were noted, and the lesions were not malignant (Figure 2).

The final diagnosis was OLP based on clinical and pathological examinations.

The efficacy of previous treatments for OLP has been poor, and relapse has been easy. Therefore, surgical treatment was recommended to the patients. The patients agreed and gave signed informed consent. Surgical excision was performed and mucosal defects were repaired with ADM (Yantai Haiao Biotechnology Ltd., China).

Tracheal intubation was performed under general anesthesia. After disinfection of the mouth, we exposed the lesion area. The lesion margin was marked with methylene blue, followed by local injection of 2% lidocaine anesthesia. We used the no. 15 circular blade to remove the lesion along the methylene blue line (Figure 3). The excised tissues were sent for pathological examination. The diagnostic results were consistent with the preoperative pathological diagnosis. An electrotome was used for hemostasis and normal saline for rinsing. ADM was washed with normal saline three times and trimmed appropriately with the tissue surface facing the wound and placed on the wound surface. ADM edge and mucosal defect edge were sutured with 3-0 Vicryl (Figure 4). The iodoform yarn strips were packed and placed above the ADM, and the wound sutures were divided into four anti-wrapping and pressurizing strands (Figure 5). The stiches and the compressive pack were removed 9 d after surgery. Patients were instructed to consume a liquid or semisolid diet (food items that could be swallowed directly) after surgery. Patients received broad-spectrum antibiotics and analgesics for 5-7 d (oral amoxicillin 500 mg every 8 h, oral ibuprofen 400 mg every 8-12 h, if needed).

Postoperative follow-up was conducted by the same investigator at 9, 15, 30, 60, and 90 d to evaluate the postoperative clinical efficacy according to pain, intraoperative maximum mouth opening, and complete healing time. The pain severity of each patient was measured by the visual analog scale (0-10). Grade 0 indicated painlessness and grade 10 represented the most severe kind of perceptible pain. Wound healing time is a traditional index to evaluate wound healing, which is defined as complete epithelialization[24].

The condition of the area of the grafted wounds, maximum mouth opening, pain, and clinical healing were assessed at postoperative follow-up visits (Table 2). In most patients, mouth opening was limited due to mild postoperative reactive pain and edema 3 d after the operation. The pain was relieved 9 d after the operation. A depression was found in the surgical area. Patients were advised to have a light diet that was fluid or semifluid and avoid mechanical stimulation to protect the wound and check it regularly after surgery. At 15 d after surgery, the wound was extensively vascularized without swelling or infection. One month after the operation, the surgical area was flat with similar mucosal tissue covering and local scar formation, and the degree of mouth opening gradually recovered. After 6 mo, the transplanted area remained stable. All patients’ mouth openings returned to normal within 2-6 mo after surgery (Figure 6). During follow-up, no patients had recurrence of OLP after surgery. The longest follow-up was 11 yr, and the shortest was 6 mo. None of the patients relapsed during follow-up. Overall, surgical results were satisfactory in all cases during follow-up. For long-term results, we need more patients to be followed up over the long term.

| Postoperative day | VAS | MMO in cm | Patients with complete healing, n (%) |

| 0 | 3.5 | 2.1 | - |

| 9 | 0.8 | 2.8 | - |

| 15 | 0.2 | 3.3 | 2 (18) |

| 30 | 0 | 3.5 | 10 (91) |

| 60 | 0 | 3.7 | 11 (100) |

| 90 | 0 | 3.8 | 11 (100) |

Surgical excision of OLP is considered an effective treatment for isolated plaques or nonhealing erosions[10]. Moss and Harman were the first to perform surgical resection of ulcerative lichen lesions in the hands and feet and used skin grafts to repair the defect after surgical resection[23]. The disadvantage of applying a skin graft is that it can cause secondary trauma and increase patient pain. Kim et al[22] performed surgical resection of lip lesions with the application of mucosal flaps, which recovered completely after 6 mo. At 17 mo after surgery, no distortion of the lip was noted. However, preparation of the mucosal flap for secondary surgery, formation of new wounds, and increased pain may cause deformity in the donor site. Pathak et al[24] performed surgical resection of oral mucosal lesions and used PRF membrane transplantation to treat oral mucosal lesions and achieved a satisfactory result. PRF membranes are fibrin scaffolds, which have entrapped platelets that release various growth factors and cytokines to promote wound healing. However, the preparation of PRF requires additional equipment for rapid centrifugation to prevent platelet dissolution, and it is unsuitable for the reconstruction of full-thickness defects[24].

ADM is a xenogenous biomaterial. The preparation of ADM is a sterile process that removes cells from the epidermis and dermis, leaving behind dermal matrix components containing collagen fibers, elastin, proteoglycan, and intact vascular scaffolds[25]. As the cells are removed, infection and immune rejection are not common. ADM can generate new angiogenesis, which makes it more resistant to infection[26]. ADM grafts are largely integrated into tissue and eventually remodeled. It can produce better color and tissue and integrate well into adjacent tissue[27]. ADM is safe, and it is easy to trim, sew, and use. It eliminates donor sites, avoids second operations and associated morbidity, and reduces postoperative discomfort and complications. However, the main disadvantage is the high cost. ADM has been utilized in a wide range of oral and maxillofacial surgery, such as correcting soft and hard tissue defects[28], immediate implant[29], and oronasal fistula repair in patients with cleft palate[30]. The results obtained with acellular dermal grafts show that the surgical procedures performed with ADM grafts have an optimistic therapeutic effect in clinical practice.

Based on the above findings, we tried to use ADM repair of OLP after surgical removal of the defect. The patients recovered almost completely after surgery, eating acidic and spicy food without sensitivity or irritation, and mouth opening was normal or slightly restricted. The transplantation area remained stable, and no recurrence was observed during follow-up of 6 mo. Compared with the above surgical defect repair method, it does not cause secondary trauma, saves operation time, and reduces patient pain. Moreover, ADM is safe, avoids immune rejection, and does not cause functional disorders such as contracture and mouth opening limitation.

Surgical intervention is an effective treatment for OLP, especially in patients with significant clinical symptoms, persistent recurrence, or failure to respond to medication. For such patients, we first used surgical excision of the lesion, and the ADM was used to repair the defect. There is no similar report in the English literature. These cases showed good results during follow-up of 6 mo to 11 yr. For long-term results, we need more patients to be followed up over the long term.

We thank the patients and their families for their support.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Stomeo F S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Manczyk B, Gołda J, Biniak A, Reszelewska K, Mazur B, Zając K, Bińczak P, Chomyszyn-Gajewska M, Oruba Z. Evaluation of depression, anxiety and stress levels in patients with oral lichen planus. J Oral Sci. 2019;61:391-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Yang H, Wu Y, Ma H, Jiang L, Zeng X, Dan H, Zhou Y, Chen Q. Possible alternative therapies for oral lichen planus cases refractory to steroid therapies. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2016;121:496-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Park SY, Lee HJ, Kim SH, Kim SB, Choi YH, Kim YK, Yun PY. Factors affecting treatment outcomes in patients with oral lichen planus lesions: a retrospective study of 113 cases. J Periodontal Implant Sci. 2018;48:213-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chiang CP, Yu-Fong Chang J, Wang YP, Wu YH, Lu SY, Sun A. Oral lichen planus - Differential diagnoses, serum autoantibodies, hematinic deficiencies, and management. J Formos Med Assoc. 2018;117:756-765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Carrozzo M, Porter S, Mercadante V, Fedele S. Oral lichen planus: A disease or a spectrum of tissue reactions? Periodontol 2000. 2019;80:105-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lauritano D, Arrica M, Lucchese A, Valente M, Pannone G, Lajolo C, Ninivaggi R, Petruzzi M. Oral lichen planus clinical characteristics in Italian patients: a retrospective analysis. Head Face Med. 2016;12:18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Piñas L, García-García A, Pérez-Sayáns M, Suárez-Fernández R, Alkhraisat MH, Anitua E. The use of topical corticosteroides in the treatment of oral lichen planus in Spain: A national survey. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2017;22:e264-e269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Thongprasom K, Dhanuthai K. Steriods in the treatment of lichen planus: a review. J Oral Sci. 2008;50:377-385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wang F, Tan YQ, Zhang J, Zhou G. Familial oral lichen planus in a 3-year-old boy: a case report with eight years of follow-up. BMC Oral Health. 2020;20:341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Samal DK, Behera G, Gupta V, Majumdar K, Khurana U. Isolated lichen planus of lower lip: a case report. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;67:151-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gupta S, Ghosh S, Gupta S. Interventions for the management of oral lichen planus: a review of the conventional and novel therapies. Oral Dis. 2017;23:1029-1042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | McCaughey C, Machan M, Bennett R, Zone JJ, Hull CM. Pimecrolimus 1% cream for oral erosive lichen planus: a 6-week randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study with a 6-week open-label extension to assess efficacy and safety. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1061-1067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Conrotto D, Carbone M, Carrozzo M, Arduino P, Broccoletti R, Pentenero M, Gandolfo S. Ciclosporin vs. clobetasol in the topical management of atrophic and erosive oral lichen planus: a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:139-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Smith RJ, Duerksen JD. Glycerol inhibition of purified and chromatin-associated mouse liver hepatoma RNA polymerase II activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1975;67:916-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kia SJ, Basirat M, Mortezaie T, Moosavi MS. Comparison of oral Nano-Curcumin with oral prednisolone on oral lichen planus: a randomized double-blinded clinical trial. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2020;20:328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bakhshi M, Gholami S, Mahboubi A, Jaafari MR, Namdari M. Combination Therapy with 1% Nanocurcumin Gel and 0.1% Triamcinolone Acetonide Mouth Rinse for Oral Lichen Planus: A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo Controlled Clinical Trial. Dermatol Res Pract. 2020;2020:4298193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yu F, Xu N, Zhao B, Ren X, Zhang F. Successful treatment of isolated oral lichen planus on lower lip with traditional Chinese medicine and topical wet dressing: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e13630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lv KJ, Chen TC, Wang GH, Yao YN, Yao H. Clinical safety and efficacy of curcumin use for oral lichen planus: a systematic review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30:605-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sobaniec S, Bernaczyk P, Pietruski J, Cholewa M, Skurska A, Dolińska E, Duraj E, Tokajuk G, Paniczko A, Olszewska E, Pietruska M. Clinical assessment of the efficacy of photodynamic therapy in the treatment of oral lichen planus. Lasers Med Sci. 2013;28:311-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rakesh N, Clint JB, Reddy SS, Nagi R, Chauhan P, Sharma S, Sharma P, Kaur A, Shetty B, Ashwini S, Pavan Kumar T, Vidya GS. Clinical evaluation of photodynamic therapy for the treatment of refractory oral Lichen planus - A case series. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2018;24:280-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Vedtofte P, Holmstrup P, Hjørting-Hansen E, Pindborg JJ. Surgical treatment of premalignant lesions of the oral mucosa. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987;16:656-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kim DH, Lim BR, Na GH, Kim EJ, Park K. Surgical excision and mucosal advancement flap: Treatment for refractory lichen planus of the lip. Dermatol Ther. 2018;31:e12695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Moss ALH, Harman RRM. Surgical treatment of painful lichen planus of the hand and foot. Br J Plast Surg. 1986;39:402-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Pathak H, Mohanty S, Urs AB, Dabas J. Treatment of Oral Mucosal Lesions by Scalpel Excision and Platelet-Rich Fibrin Membrane Grafting: A Review of 26 Sites. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;73:1865-1874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ellis CV, Kulber DA. Acellular dermal matrices in hand reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:256S-269S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Moyer HR, Hart AM, Yeager J, Losken A. A Histological Comparison of Two Human Acellular Dermal Matrix Products in Prosthetic-Based Breast Reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2017;5:e1576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Balaji VR, Ramakrishnan T, Manikandan D, Lambodharan R, Karthikeyan B, Niazi TM, Ulaganathan G. Management of gingival recession with acellular dermal matrix graft: A clinical study. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2016;8:S59-S64. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Griffin TJ, Cheung WS, Hirayama H. Hard and soft tissue augmentation in implant therapy using acellular dermal matrix. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2004;24:352-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Park JB. Immediate implantation with ridge augmentation using acellular dermal matrix and deproteinized bovine bone: a case report. J Oral Implantol. 2011;37:717-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | El-Kassaby MA, Khalifah MA, Metwally SA, Abd ElKader KA. Acellular dermal matrix allograft: An effective adjunct to oronasal fistula repair in patients with cleft palate. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2014;4:158-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |