Published online Dec 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i34.10659

Peer-review started: February 26, 2021

First decision: May 11, 2021

Revised: May 17, 2021

Accepted: October 27, 2021

Article in press: October 27, 2021

Published online: December 6, 2021

Processing time: 276 Days and 21.3 Hours

Hypoparathyroidism is a rare disease that may occur due to primary or secondary etiologies. The estimated incidence in the United States is 24–37/100000 person-years. Congestive heart failure associated with hypocalcemia due to hypoparathyroidism is an even rarer presentation.

Here, we present a 64-year-old woman with congestive heart failure following hypocalcemia. The patient was transferred to our emergency department with complaints of rapidly progressive dyspnea, shortness of breath and heaviness of the chest for 4 d. She had a history of undergoing thyroidectomy and partial tracheotomy 2 years prior due to a malignant thyroid tumor. Muscle spasms had been present 1 year ago, and cataracts were treated with intraocular lens replacement in both eyes. Most tests were within normal ranges, except serum calcium at 1.33 mmol/L (2.20–2.65 mmol/L), ionized calcium at 0.69 mmol/L (1.15–1.29 mmol/L), and parathyroid hormone at < 1.0 pg/mL (12–88 pg/mL). Echocardiography revealed an ejection fraction of 28.48%. Cardiac function was quickly reversed by restoring the serum calcium concentration. Significant improvements were noted with an ejection fraction of up to 48.50% at follow-up.

For patients with potential hypocalcemia, monitoring calcium levels and dealing with hypocalcemia in time to avoid serious complications are important.

Core Tip: Hypoparathyroidism-related cardiomyopathy is rare but reversible. We present a rare case of congestive heart failure associated with hypocalcemia in an elderly female with a history of thyroidectomy. The heart failure was reversed rapidly by infusion of calcium gluconate. With the supplementation of calcium, the cardiac function was maintained very well. The patient also presented with a history of cataracts. This case highlights that, for patients with potential hypocalcemia, we need to supplement calcium and closely monitor calcium levels to manage the hypocalcemia in time to avoid serious complications, such as cardiac complications or cataracts.

- Citation: Wang C, Dou LW, Wang TB, Guo Y. Reversible congestive heart failure associated with hypocalcemia: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(34): 10659-10665

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i34/10659.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i34.10659

Hypoparathyroidism is a rare disease that may occur due to primary or secondary etiologies. The level of parathyroid hormone is low; therefore, serum concentrations of calcium and phosphorus cannot be maintained within a narrow normal range, resulting in hypocalcemia and hyperphosphatemia[1]. Hypocalcemia has many manifestations, such as muscle spasms, hair loss, dry skin and brittle nails[2]. Here, we present a case of chronic hypocalcemia-induced cardiomyopathy following hypoparathyroidism, manifesting as congestive heart failure (CHF), which was quickly reversed by restoring the serum calcium concentration (Table 1).

| Timeline | Events | Additional information |

| 2018 | Thyroidectomy and partial tracheotomy | Iodine-131 radiotherapy every six months thereafter (3 times in total) |

| June 2019 | Muscle spasms | Intraocular lens implantation in both eyes due to cataracts |

| October 26, 2020 | Rapidly progressive dyspnea, shortness of breath | Treated for CHF at a local hospital without any effect |

| October 30, 2020 | Transferred to our ER department | - |

| November 1, 2020 | Symptoms resolved greatly | Administration of a 10% calcium gluconate |

| December 2, 2020 | Follow up 1 mo later | Oral calcium carbonate (0.75 g qid) and calcitriol (0.25 μg bid) |

A 64-year-old woman was transferred to the emergency department on October 30, 2020 with complaints of insidious onset but rapidly progressive dyspnea, shortness of breath and heaviness of the chest for 4 d.

The patient had progressive dyspnea and shortness of breath without obvious cause on October 26, 2020. Symptoms were present during activity or at rest, which could last for about 1 h and then resolve spontaneously. There was no fever, cough, sputum, chest pain, hemoptysis, or lower limb edema. On October 29, 2020, she went to a local hospital for symptom aggravation, and congestive cardiac failure was diagnosed. Diuretic treatment was adopted. No effect was observed. Thereafter, she was transferred to our hospital for further evaluation and treatment.

She had a history of undergoing thyroidectomy and partial tracheotomy in 2018 due to a malignant thyroid tumor, followed by iodine-131 radiotherapy every 6 mo thereafter (3 times in total). Intraocular lens implantation was performed in both eyes in 2019 due to cataracts. Muscle spasms were also present in 2019. Diabetes mellitus was noted. She was taking levothyroxine (175 μg qd), calcium carbonate (0.5 g tid) and acarbose (100 mg qd) regularly.

Personal and family history were unremarkable.

On general physical examination, the patient was conscious with a blood pressure of 140/80 mmHg, respiratory rate of 16 breaths/min, and pulse rate of 104 beats/min. Auscultation revealed reduced air entry in both lungs. Edema of the lower limbs was noted. No cyanosis, clubbing or lymphadenopathy were observed. Abdominal and central nervous system examinations were unremarkable.

The following levels (normal range) were revealed. Routine blood test showed hemoglobin was 116 g/L (115–150 g/L). Biochemical tests revealed serum calcium was 1.33 mmol/L (2.20–2.65 mmol/L), ionized calcium was 0.69 mmol/L (1.15–1.29 mmol/L), phosphorus was 2.43 mmol/L (0.81–1.45 mmol/L), serum magnesium was 0.67 mmol/L (0.7–1.05 mmol/L), albumin was 38.8 g/L (40–55 g/L), total bilirubin was 9.3 µmol/L (3–21 µmol/L), and creatinine was 65 µmol/L (45–84 µmol/L). Infection related markers showed that C-reactive protein was 11.1 mg/L (0–10 mg/L), procalcitonin was 0.071 ng/mL (< 0.5 ng/mL). Cardiac-related markers showed that B-brain natriuretic peptide was 730 pg/mL (0–100 pg/mL). High-sensitivity troponin, myoglobin and creatine kinase MB were within normal ranges. Parathyroid hormone was < 1.0 pg/mL (12–88 pg/mL). The arterial blood gas level was within normal limits.

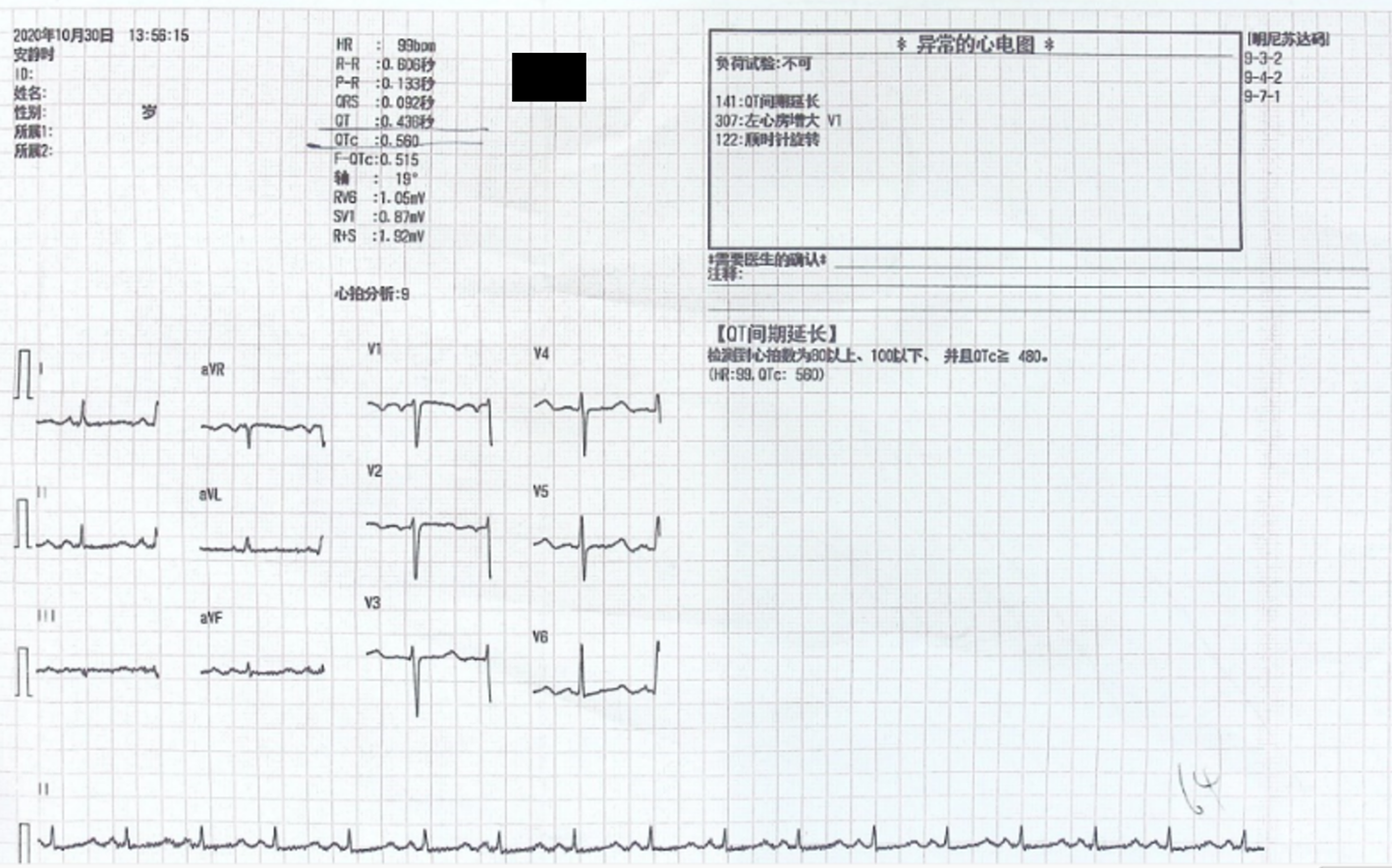

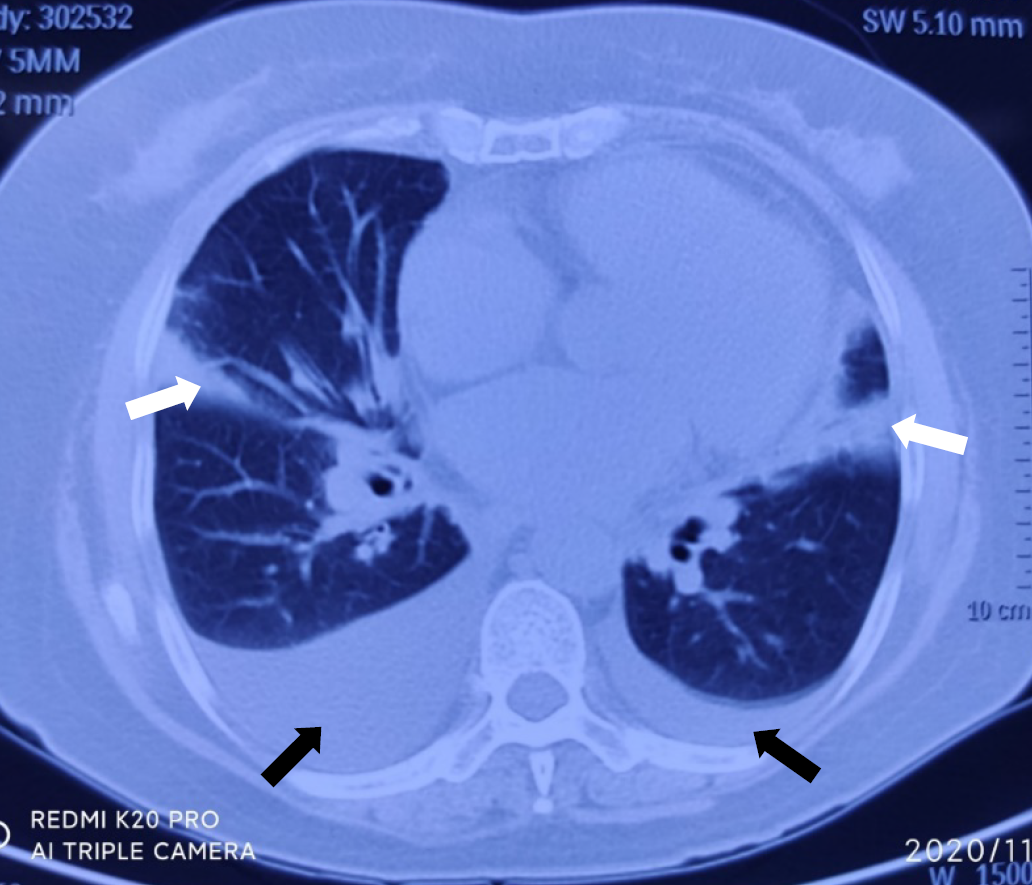

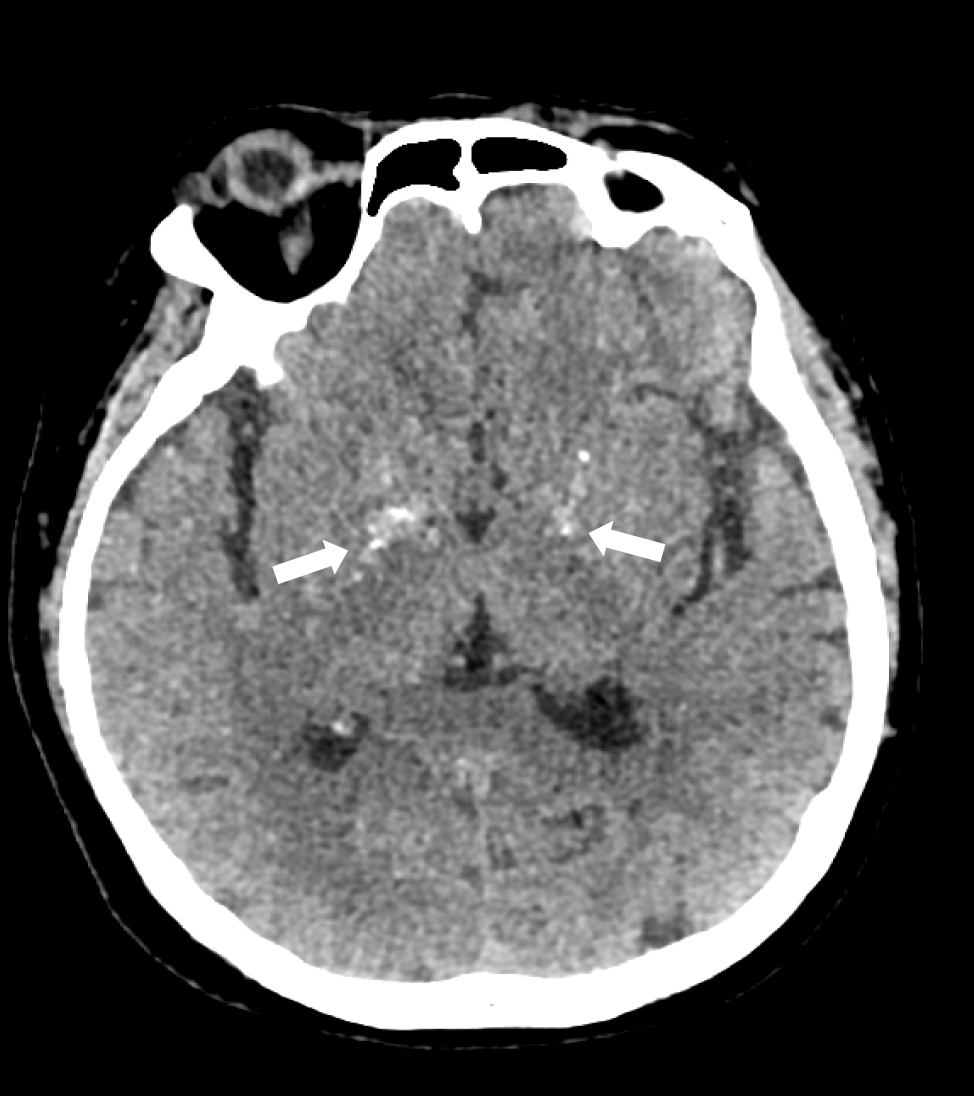

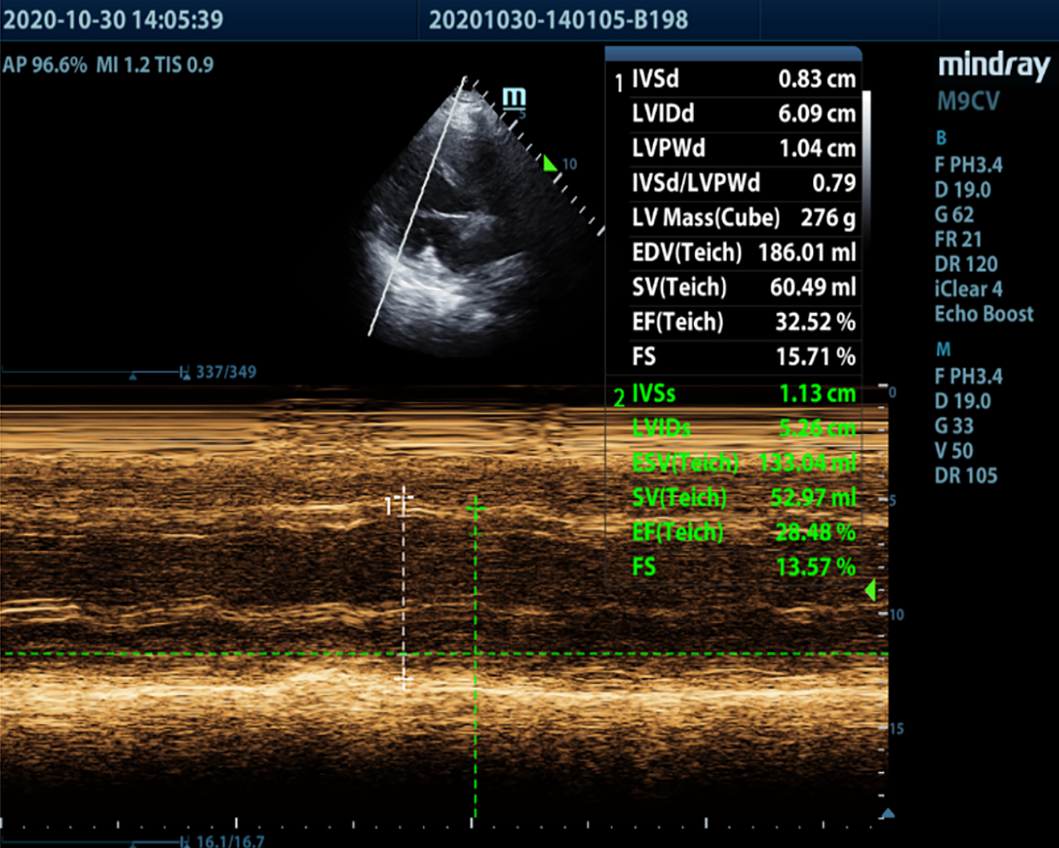

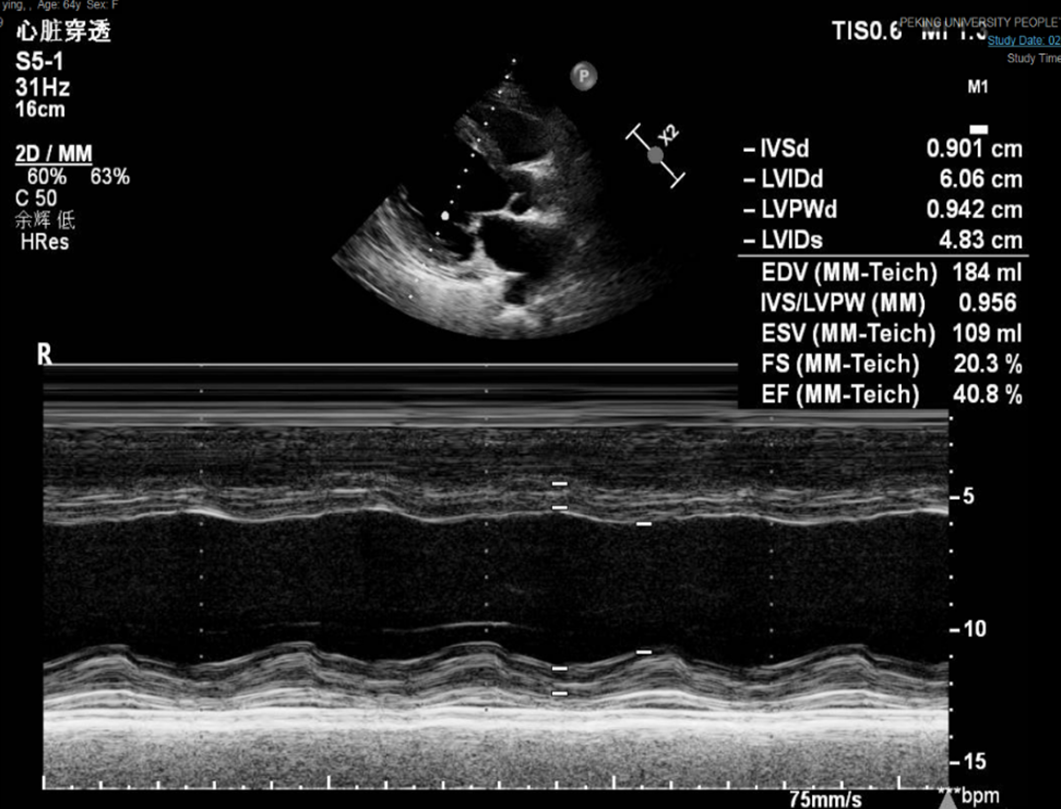

Electrocardiography on admission showed a prolonged corrected QT interval (0.560 s) (Figure 1). Chest computed tomography showed bilateral lung infection, mild enlargement of the left atrium and ventricle, and bilateral pleural and pericardial effusions (Figure 2). Head computed tomography showed bilateral symmetric calcification in the basal ganglia (Figure 3). Echocardiography revealed that the left heart was enlarged with reduced movement of the left ventricle and a small amount of pericardial effusion with an ejection fraction (EF) of 28.48% on admission (Figure 4).

The final diagnosis of the presented case was CHF associated with hypocalcemia and hypoparathyroidism. Myocardial infarction and pulmonary heart disease were excluded based on the history, electrocardiography, echocardiography and chest computed tomography.

The patient was administered a 10% calcium gluconate 100 mL (930 mg of elemental calcium) infusion in 1000 mL of 5% dextrose at a rate of 50 mL/h. Within 2 d, the serum calcium level increased from 1.33 mmol/L to 2.14 mmol/L, ionized calcium level increased from 0.69 mmol/L to 1.11 mmol/L, and echocardiography showed an EF of 40.80% (Figure 5).

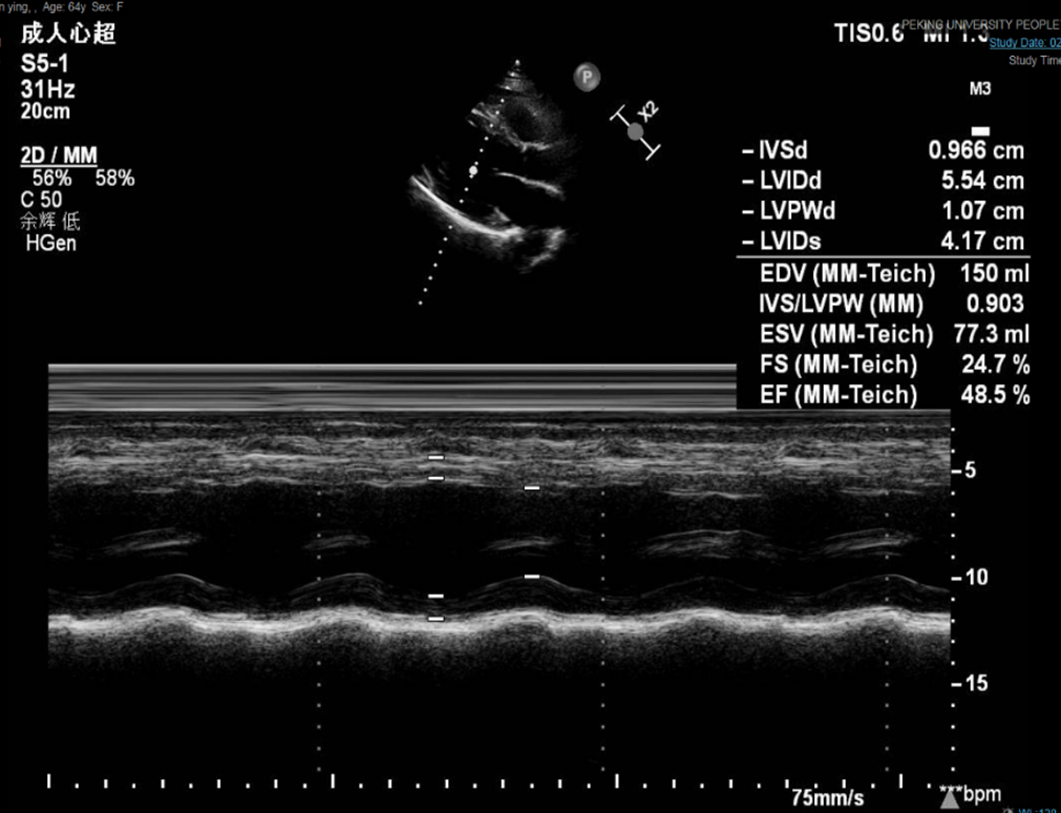

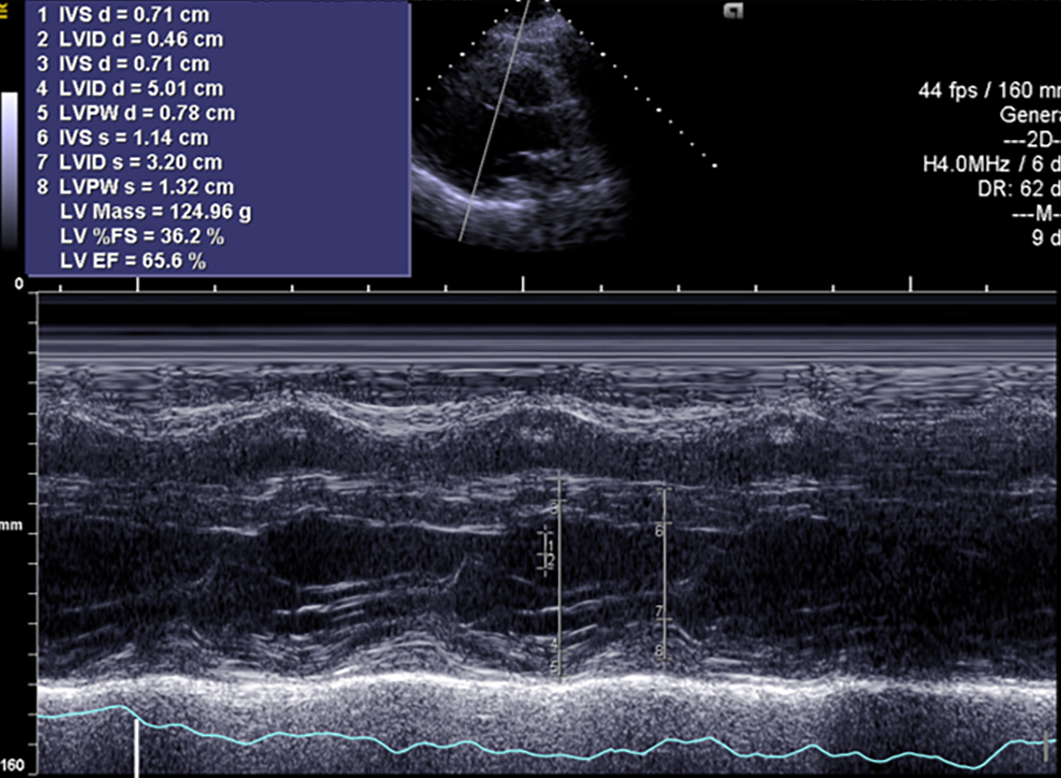

The symptoms of CHF were quickly alleviated. The patient was then discharged with oral calcium carbonate (0.75 g qid) and calcitriol (0.25 μg bid). At the 1-mo follow-up, the patient had no symptoms of CHF, and echocardiography showed an EF of 48.50% (Figure 6). At the 4-mo follow-up, the patient had no symptoms of CHF, and echocardiography showed left heart size and left ventricular systolic function returned to normal with no pericardial effusion. EF was 65.60% (Figure 7).

Hypoparathyroidism is a relatively uncommon disease. The estimated incidence in the United States is 24–37/100000 person-years[3]. It is characterized by hypocalcemia due to absent or low parathyroid hormone levels. The major function of parathyroid hormone is to maintain the level of serum calcium by binding to cell surface receptors in the bone and kidneys, thereby modulating the calcium concentration in the blood. Approximately 75% of cases are due to neck surgery[3]. Other etiologies include autoimmune diseases or hereditary hypoparathyroidism, such as DiGeorge syndrome, autosomally inherited hypoparathyroidism and autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type I.

Our patient had undergone extensive thyroid surgery 2 years prior and had developed symptoms of hypoparathyroidism for 1 year, even though she was taking calcium carbonate. With prolonged duration of hypocalcemia, dilated cardiomyopathy, a severe complication, developed, which was rapidly and easily reversed by calcium supplementation. Severe complications of hypocalcemia include confusion, muscle spasms, numbness in the hands, feet and face, depression, hallucinations, muscle cramps, brittle nails, and an increased risk of bone fractures. Dilated cardiomyopathy caused by hypocalcemia is very rare but reversible[4,5]. Unfortunately, the reversibility might not be complete[4]. Fortunately, cardiac function was fully restored after supplementation of calcium. Normal levels of calcium are critical for cardiac function and for the reduction in mortality[6].

The patient underwent surgery in both eyes for cataracts, which might also have been a manifestation of her prolonged hypocalcemia. The proposed mechanism of cataract formation from hypocalcemia is membrane damage due to low calcium levels in the aqueous humor and increased sodium levels in the lens[7]. Sharp vigilance about the possibility of cataracts induced by hypocalcemia should be maintained, although diabetes mellitus may also contribute to cataract formation[8].

In conclusion, prolonged hypocalcemia should be avoided, especially in patients after thyroid surgery. For patients with hypoparathyroidism, serum calcium be monitored along with regular ophthalmic checks. CHF may develop following hypoparathyroidism and cataracts.

For patients with potential hypocalcemia, we need to supplement calcium and closely monitor serum calcium levels to manage hypocalcemia in time to avoid serious complications, such as cardiac complications or cataracts.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kharlamov AN S-Editor: Liu M L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu M

| 1. | Bilezikian JP. Hypoparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105:1722-1736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hakami Y, Khan A. Hypoparathyroidism. Front Horm Res. 2019;51:109-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Abate EG, Clarke BL. Review of Hypoparathyroidism. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2016;7:172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Newman DB, Fidahussein SS, Kashiwagi DT, Kennel KA, Kashani KB, Wang Z, Altayar O, Murad MH. Reversible cardiac dysfunction associated with hypocalcemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. Heart Fail Rev. 2014;19:199-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Saini N, Mishra S, Banerjee S, Rajput R. Hypocalcemic cardiomyopathy: a rare presenting manifestation of hypoparathyroidism. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12:e229822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Miura S, Yoshihisa A, Takiguchi M, Shimizu T, Nakamura Y, Yamauchi H, Iwaya S, Owada T, Miyata M, Abe S, Sato T, Suzuki S, Oikawa M, Yamaki T, Sugimoto K, Kunii H, Nakazato K, Suzuki H, Saitoh S, Takeishi Y. Association of Hypocalcemia With Mortality in Hospitalized Patients With Heart Failure and Chronic Kidney Disease. J Card Fail. 2015;21:621-627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Daba KT, Weldemichael DK, Mulugeta GA. Bilateral hypocalcemic cataract after total thyroidectomy in a young woman: case report. BMC Ophthalmol. 2019;19:233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ang MJ, Afshari NA. Cataract and systemic disease: A review. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2021;49:118-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |