Published online Nov 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i32.9741

Peer-review started: June 3, 2021

First decision: July 5, 2021

Revised: May 26, 2021

Accepted: September 7, 2021

Article in press: September 7, 2021

Published online: November 16, 2021

Processing time: 159 Days and 18.1 Hours

Hands are one of the most common burn sites in children. Hypertrophic scar contractures in hands after wound healing result in further reductions in their range of motion (ROM), motility, and fine motor activities. Rehabilitation can improve the function of hands. But the optimal time of rehabilitation intervention is still unclear. Therefore, this study was designed to investigate the effects of early rehabilitation management of paediatric burnt hands and to compare the efficacy between early and later rehabilitation intervention.

To investigate the effects of early rehabilitation management of paediatric burnt hands.

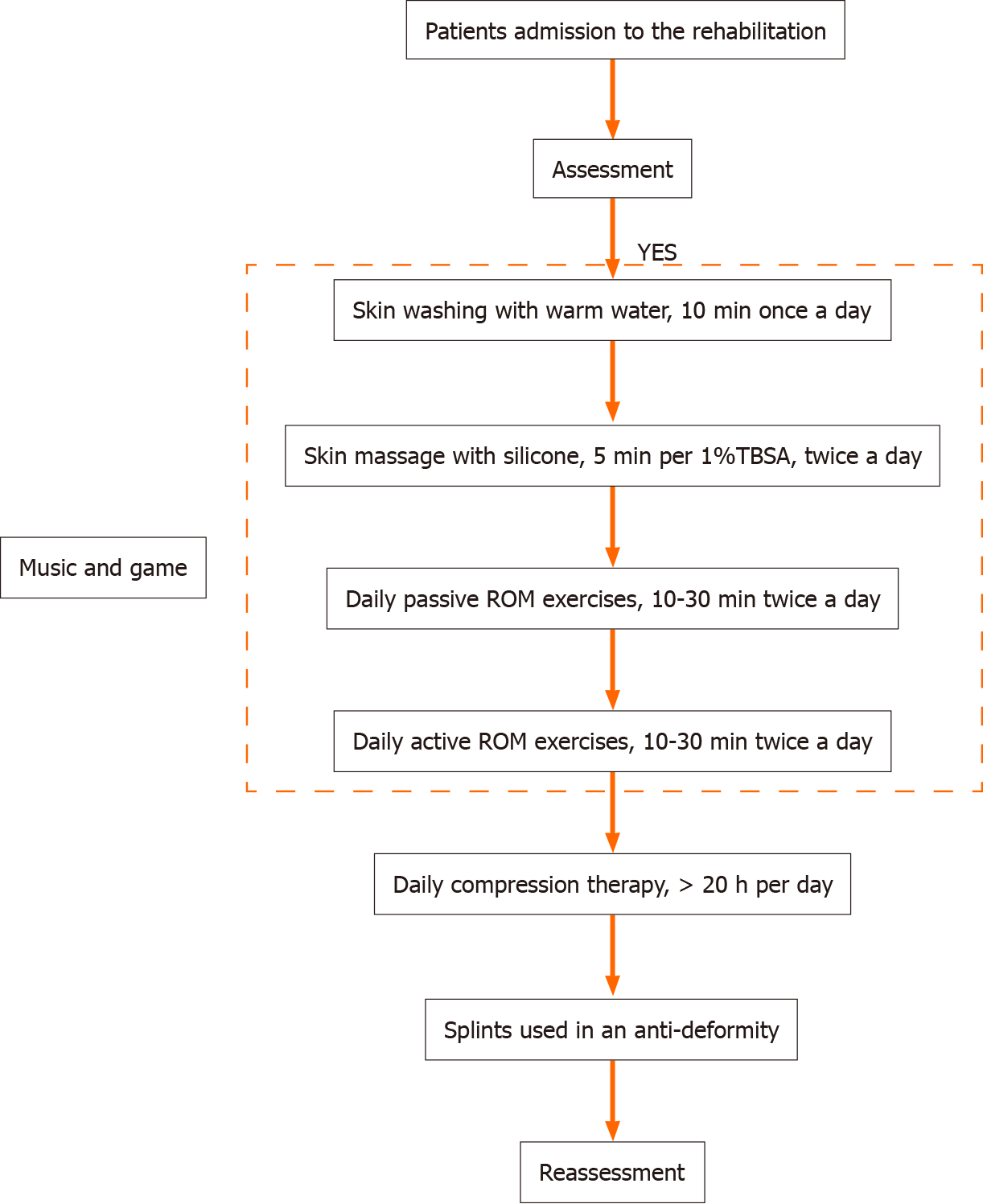

A total of 52 children with burnt hands were allocated into the early intervention group (≤ 1 mo from onset) and a late intervention group (> 1 mo from onset) between January 2016 and December 2017. The children received the same rehabilitation programme including skin care, scar massage, passive ROM exercises, active ROM exercises, compression therapy, orthotic devices wearing and game or music therapy. Rehabilitation assessments were performed before and after the rehabilitation treatment.

In the early intervention group, the ROM of the hands was significantly improved after rehabilitation (P = 0.001). But in the late group the effect was not significant statistically (P = 0.142). In the early group, 38.5% of the patients showed significant improvement, while in the late group, 69.2% of the patients showed no significant improvement. The time from onset to posttraumatic rehabilitation (P = 0.0007) and length of hospital stay (P = 0.003) were negatively correlated with the hand function improvement. The length of rehabilitation stay was positively correlated with the hand function improvement (P = 0.005).

These findings suggest that early rehabilitation might show better results in terms of ROM.

Core Tip: This is a retrospective study to evaluate the efficacy of early rehabilitation management of paediatric burnt hands. Hands are one of the most common burn sites in children. Hypertrophic scar contractures in hands after wound healing result in further reductions in their range of motion (ROM), motility, and fine motor activities. In order to investigate the situation of hand function in burned children with rehabilitation, we analyzed the demographic and medical information in these burned children and compared the efficacies of early rehabilitation and late rehabilitation for children with hand burns. We found that in the early intervention group, 38.5% of the patients showed significant improvement in the active ROM, while in the late group, 69.2% of the patients showed no significant improvement. Hand function improvement in burned children was negatively correlated with the time from onset to posttraumatic rehabilitation intervention, while the length of rehabilitation stay was positively correlated with the improvement of hand function.

- Citation: Zhou YQ, Zhou JY, Luo GX, Tan JL. Effects of early rehabilitation in improvement of paediatric burnt hands function. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(32): 9741-9751

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i32/9741.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i32.9741

Due to their poor cognitive ability and self-control, children are very susceptible to various accidental injuries in daily life, and burns are the most common of such injuries[1]. With the advancement of medical treatment, the survival rate was much increased and their lives are often saved. However, during the healing of burn wounds, children’s activities are limited due to continuous bandage fixation, edema, and pain in the wounds, and hypertrophic scar contractures after wound healing result in further reductions in their range of motion (ROM), dexterity, and fine motor activities. These limitations will affect their performance in daily activities and school work. Other than range of motion, the scar on the hand would also affect the cosmesis. Thus some children are susceptible to discrimination from other children during their growth and development, particularly when the hands are often exposed in day to day contact[2]. They might experience psychological stress, depression and anxiety[3].

Hands are one of the most common burn sites[4], and hand burns account for approximately 33.2% of all location of burns[5]. An analysis of children with burns admitted to our department in the past 5 years showed that around 38.1% of them had burns on the hands[6]. As children are still growing and continue their development, their scars might be more severe when compared to adults. Therefore, they might have more scar contractures and deformities as they grow up[7]. Palmar burns would cause finger flexion deformity, leading to impairment of finger extension. Dorsal burns could cause extension deformities, leading to impaired flexion of the interphalangeal (IP) joint and the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint. Burns involving the whole hand would result in restricted joint flexion and extension, thus causing joint stiffness[8]. It was even more challenging to manage the small hands of children both from surgical intervention and rehabilitation. Currently, there is no standard rehabilitation program for management of burnt hands for children. It is believed that early rehabilitation would enhance better results, particularly when managing the small joints of fingers and thumb. This is a retrospective study comparing those children who received therapy within one month after injury and those who received treatment after one month of injury.

This study included pediatric outpatients and inpatients with hand burns who underwent systematic rehabilitation at the burn center of a large regional hospital between January 2016 and December 2017. This retrospective study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the hospital. General information (age, gender), cause of injury, severity of injuries, date of admission, date started therapy, length of rehabilitation programme, education levels of parents and family background were collected. The passive range of motion (PROM) of the joints of the hands was measured using goniometers and inclinometers. According to the time from onset to the start of rehabilitation, the patients were divided into the early intervention group (≤ 1 mo from onset) and a late intervention group (> 1 mo from onset).

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients aged 0-14 years old; (2) Patients with deep second- or third-degree burns and the involvement of the interphalangeal joint or/and MCP joint; and (3) Patients who received systematic rehabilitation.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients with first-degree or superficial second-degree burns; (2) Patients with hand burns that did not involve the interphalangeal joint or MCP joint; and (3) Patients who did not receive systematic rehabilitation.

Skin care: Skin care was performed by the parents of the children, and the injured parts were cleaned with warm water every day. During cleansing, dry skin and scabs were gradually removed as much as possible, and the residual wounds were redressed with ointments and gauze once a day.

Scar massage: The healed wound was massaged by the rehabilitation therapist. During the massage, silicone ointments were used as the massage medium. The scar tissue was massaged using the thumb pads or the palms. It took approximately 5 minutes to massage 1% of the total body surface area (TBSA), and each patient was massaged twice daily.

PROM exercises: The rehabilitation therapists conducted PROM exercises, which were mainly performed along the direction and range of the physiological joint movement of the injured joint. Each time the hand obtained the desired posture, the posture was maintained for 15-20 s. Exercises along each direction of physiological movement were performed 10 times, twice each day.

Active range of motion (AROM) exercises: The patients completed AROM exercises on their parents or under the guidance of the rehabilitation therapists. After each PROM exercise, the patient was allowed to actively move the injured joint along the range and direction of its physiological movement. Each time the hand reached the desired posture, the posture was maintained for 10 s. Exercises along each direction of physiological movement were performed 10 times, twice each day.

Compression therapy: The rehabilitation therapists introduced compression gloves or self-adhesive bandages for compression therapy on the affected hands of the children. The pressure was increased gradually, and the maximum pressure that did not affect the blood flow at the fingertips of the children was used. Compression therapy was applied for more than 20 h daily.

Orthotic devices: Static and dynamic orthoses of the anti-contracture position were designed for each according to the injured site(s).

Games or music therapy: During the rehabilitation process, the children could play games according to their interests. A music therapist also provided music therapy intervention to distract the children and reduce their sense of fear, making them more compliant with the treatment. (Figures 1 and 2).

Rehabilitation therapists performed rehabilitation assessments of the patients before and after they received rehabilitation treatment. Goniometers and inclinometers were used to measure the AROM of various joints of the hands of the burned children. The ROM was evaluated using total active movement (TAM), where TAM = flexion position [MCP + proximal interphalangeal (PIP) + distal interphalangeal (DIP)] – extension position (MCP + PIP + DIP). The normal AROM of one hand was 1250°, and the degree of decrease in the AROM of the children before rehabilitation was divided into mild restriction, moderate restriction, severe restriction, and significant restriction, which corresponded to [(1250° – pretreatment TAM)/1250°] values of ≤ 25%, 25%-≤ 50%, 50%-≤ 75% and > 75%, respectively. AROM before and after rehabilitation were compared, and the degree of improvement in the joints of the hands was classified as no improvement, mild improvement, moderate improvement, and significant improvement, which corresponded to [(posttreatment TAM – pretreatment TAM)/ pretreatment TAM] values of ≤ 25%, 25%-≤ 50%, 50%-≤ 75% and > 75%, respectively.

Data are expressed as mean and standard deviation and number and percentages and were analyzed using SPSS 23.0 statistical software. The general data of the two groups used the chi-square test and the t-test. Correlation analysis was performed using ordered logistic regression. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 71 children with hand burns in 2016 to 2017 were considered for inclusion. Among them, 52 children met the inclusion criteria, and 19 patients lacked posttreatment data due to termination of treatment. Among the enrolled patients, 36 were male (69.2%), and 16 were female (30.8%). Their ages ranged from 1 to 14 years. The causes of injury included hot liquid, flames, electricity, and reconstructive surgery of the hand. There were 15 (28.8%) urban children and 37 (71.2%) rural children. There were 12 (23.1%) patients whose parents had an education level of elementary school or below, 32 (61.5%) patients whose parents had an education level of middle school or high school, and 8 (15.4%) patients whose parents had an education level of college or above. According to the time from onset to rehabilitation, the patients were divided into an early intervention group (≤ 1 mo from onset) and a late intervention group (> 1 mo from onset). The early intervention group received rehabilitation time was 17.96 + 25.24 (d). The length of rehabilitation stay in late intervention groups was 22.19 + 18.65 (d). There was no significant difference in the general data (P > 0.05, Table 1) or the degree of the decrease in PROM (P > 0.05, Table 2) between the two groups.

| Groups | Within 1 mo | More than 1 mo | P value |

| Number of patients | 26 | 26 | |

| Sex | 0.548 | ||

| Male (n) | 19 | 17 | |

| Female (n) | 7 | 9 | |

| Age at injury, mean ± SD (yr) | 5.35 ± 4.32 | 5.46 ± 4.33 | 0.924 |

| Hand injury | 0.105 | ||

| Palm of hand | 7 | 3 | |

| Dorsum of hand | 2 | 0 | |

| Palm and dorsum of hand | 17 | 23 | |

| Etiology (n) | 0.188 | ||

| Scald | 9 | 8 | |

| Fire/flame | 5 | 10 | |

| Electricity | 3 | 0 | |

| Plastic surgery | 9 | 8 | |

| Length of stay, mean ± SD (d) | 47.65 ± 44.95 | 27.50 ± 24.75 | 0.051 |

| Rehabilitation length of stay, mean ± SD (d) | 17.96 ± 25.24 | 22.19 ± 18.65 | 0.495 |

| time post injury of Rehabilitation, mean ± SD (d) | 17.62 ± 5.09 | 107.58 ± 62.18 | 0.000 |

| Education level of parents | 0.659 | ||

| Primary school | 5 | 7 | |

| Middle school | 16 | 16 | |

| college | 5 | 3 | |

| Live | 0.358 | ||

| Urban | 6 | 9 | |

| Suburban | 20 | 17 |

| Groups | ≤ 25% | 25%-50% | 50%-75% | > 75% | Total |

| Patients within 1 mo after injury | 4 | 9 | 5 | 8 | 26 |

| Patients with more than 1 month after injury | 12 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 26 |

| Total | 16 | 13 | 10 | 13 | 52 |

There was no significant difference in pretreatment ROM between the two groups (P = 0.057). The pretreatment ROM and posttreatment ROM of the hand joints of the burned children in the early intervention group (≤ 1 mo from onset) were 554.04 ± 358.37 and 888.85 ± 345.56, respectively, and the ROM was significantly improved after rehabilitation (P = 0.001). The pretreatment ROM and posttreatment ROM of the hand joints of the burned children in the late intervention group (> 1 mo from onset) were 752.12 ± 375.55 and 901.73 ± 346.38, respectively; although the pretreatment ROM was better than the posttreatment ROM, the difference was not significant (P = 0.142, Table 3).

| Groups | Within 1 mo | More than 1 mo | P value |

| Pre-rehabilitation therapy | 554.04 ± 358.37 | 752.12 ± 375.55 | 0.057 |

| Post-rehabilitation therapy | 888.85 ± 345.56 | 901.73 ± 346.38 | 0.089 |

| P value | 0.001 | 0.142 |

In the early intervention group, 10 (38.5%) patients had significant improvement (> 75%), 7 patients (26.9%) had no improvement (≤ 25%), 5 patients (19.2%) had mild improvement (25%-≤ 50%), and 4 patients (15.4%) had moderate improvement. In the late intervention group, 18 patients (69.2%) had no improvement (≤ 25%), 3 patients (11.5%) had mild improvement (25%-≤ 50%), 1 patient (3.8%) had moderate improvement (50%-≤ 75%), and 4 patients (15.4%) had significant improvement (> 75%). The early intervention group showed significantly greater improvement than the late intervention group. In the moderate improvement group and the significant improvement group, the proportion of children who received early rehabilitation intervention was significantly higher than the proportion of children who received late rehabilitation intervention. (P = 0.021, Table 4).

| Groups | ≤ 25% | 25%-50% | 50%-75% | > 75% | Total |

| Patients within 1 mo after injury | 7 (26.9) | 5 (19.2%) | 4 (15.4%) | 10 (38.5%) | 26 |

| Patients with more than 1 mo after injury | 18 (69.2%) | 3 (11.5%) | 1 (3.8%) | 4 (15.4%) | 26 |

| Total | 25 | 8 | 5 | 14 | 52 |

The time from onset to posttraumatic rehabilitation intervention (P = 0.0007) and the length of hospital stay (P = 0.003) were negatively correlated with the improvement of hand function. The length of rehabilitation stay (days) (P = 0.005) was positively correlated with the improvement of hand function. In addition, the improvement of hand function in pediatric inpatients was better than that in pediatric outpatients (P = 0.027). Compared with children with burns caused by hot liquid and children who had undergone reconstructive surgery of the hand, children with flame burns (P = 0.011) and electric burns (P = 0.012) showed greater improvement in hand function after rehabilitation (Table 5).

| Variable | B | Exp (B) | SE | P value | 95%CI |

| Male | -0.566 | 0.568 | 0.883 | 0.522 | -2.296-1.165 |

| Age | -0.210 | 0.811 | 0.147 | 0.065 | -0.056-0.017 |

| Inpatient | 3.909 | 49.849 | 1.771 | 0.027 | 0.439-7.379 |

| Hospital length of stay (d) | -0.091 | 0.913 | 0.031 | 0.003 | -0.151-(-0.031) |

| Time post injury of rehabilitation intervention | -0.038 | 0.963 | 0.014 | 0.007 | -0.065-(-0.011) |

| Rehabilitation (d) | 0.130 | 1.139 | 0.047 | 0.005 | 0.039-0.221 |

| Fire/flame | 3.851 | 47.040 | 1.519 | 0.011 | 0.874-6.829 |

| Electricity | 4.591 | 98.593 | 1.817 | 0.012 | 1.029-8.153 |

The hand is essential to daily activities and is one of the most vulnerable parts of the human body. Although both hands only account for 5% of TBSA, more than 80% of patients with severe burns have hand burns. The American Burn Association categorizes hand burns as a serious injury[9]. The loss of hand function results in the loss of 54% of the total function of the body. In addition to causing dysfunctions, hand burns also have physiological, social, and psychological consequences that directly affect the quality of life of children. Systematic rehabilitation training combined with focused therapy and surgical intervention help to improve hand function[10]. In this study, a model of collaboration between the rehabilitation therapist, the music therapist, and the parents of the burned child was adopted for systematic rehabilitation of hand function.

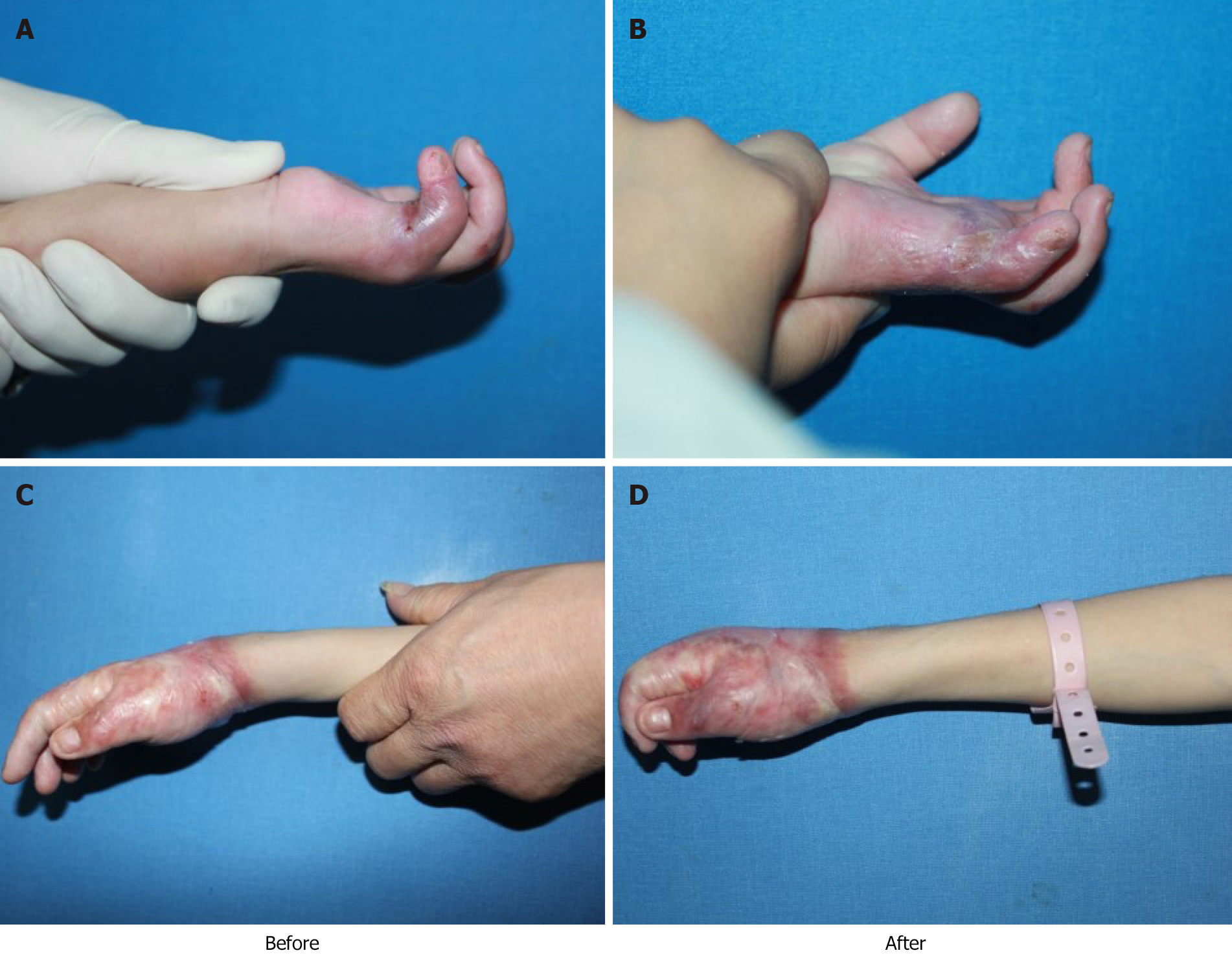

Burn rehabilitation therapists are an important part of burn rehabilitation. They guide or train patients to perform rehabilitation exercises or use various braces and equipment to maintain the elasticity of the burned skin, the muscle strength, and the ROM to promote functional recovery[11]. Postburn edema management, brace fixation, active and passive exercises, scar management, and training in activities of daily life are the key therapeutic elements for achieving the best recovery after burn injury. A study reported that the disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand score of patients decreased from 60.9 to 33.9 points through systematic hand function training conducted by a therapist[12]. The role of rehabilitation therapists is more important in the rehabilitation of burned children, especially children in the growth period and toddlers, than it is in the rehabilitation of burned adults[13]. Additionally, education for the parents of the burned children is also key to successful treatment[14]. In our study, a child rehabilitation therapist conducted systematic rehabilitation training for children aged 0-14 years that included cleaning, care and massage of the healed skin, AROM and PROM exercises of the joints of the hands, compression therapy, the use of orthotic devices, and games and music therapies involving music therapists and the parents of the children. After this treatment, the TAM and ROM of the burned hands were improved (Figure 3). During the treatment process, children typically have a low level of compliance due to pain, swelling, itching and other factors. To promote children’s acceptance of rehabilitation treatment, trust between the therapists and the children was established, and the parents of the children participated in the entire treatment process to rebuild their confidence by helping them to take the initiative to cooperate and carrying out evaluations. In our study, 76.9% of the parents of the children had an education level of middle school or above, and they could communicate well and cooperate with the therapists in the treatment of the children. Our country is a developing country; young and middle-aged people in suburban need to go out to work to make a living, leaving behind children who are mainly cared for by their grandparents. The grandparents are old and do not have sufficient ability to supervise and take care of the children; therefore, the rate of accidents among rural children is higher than that among urban children[15]. Our study also found that 71.2% of the children with hand burns were from suburban.

Rehabilitation for hand burns needs to start during the acute stage of the burn and should focus on the reduction of wound edema, the maintenance of anti-contracture positioning, and AROM and PROM exercises. Rehabilitation training during wound healing mainly includes scar prevention, edema control, new skin protection, and exercises to prevent joint contracture[16]. Rehabilitation training after wound healing includes the prevention and treatment of scars and the alleviation of joint contracture[17]. Studies have shown that the timing of intervention for burn rehabilitation is closely related to the prognosis of burn patients. Early rehabilitation intervention can reduce scars, avoid deformities, increase muscle strength, improve ROM, and promote the recovery of hand function in patients[18-20]. Our study results also suggested that the rehabilitation of hand function was negatively correlated with the time from the onset of injury to the initiation of posttraumatic rehabilitation intervention time in children. The sooner that rehabilitation was initiated and the longer the duration of rehabilitation was, the greater the improvement of hand function. The hand function of the early intervention group was significantly better than that of the late intervention group. Therefore, it is suggested that the rehabilitation of hand function in children with burns should start in the acute stage. Even if the wounds are not healed, systematic rehabilitation can be performed.

Since children are in the growth and development stage, if the growth of the burned limbs exceeds the speed of scar expansion, scar contractures will continue to develop. Therefore, after burns, the incidence of hand contractures is higher in children than in adults[21]. Children with hand burns are prone to swan-neck deformity, boutonniere deformity and syndactyly[22]. Therefore, in our study, we created targeted anti-contracture orthotic devices, including static orthoses (mainly used for night wear) (Figure 2G) and dynamic orthoses (worn by the child during the day) (Figure 2H) based on the hand injury of each child. According to the principle of creep in human soft tissue, the elastic limit of the ends of the tissue was maintained continuously to passively elongate the tendons, ligaments and joint capsules around the joint, thereby improving the mobility of the joints of the hand. At the same time, web-space pressure inserts were created to prevent syndactyly caused by adhesion (Figure 2E). Because the fifth finger is shorter than the other fingers and is located on the ulnar side, it is prone to contracture deformity after burns. Therefore, the orthosis designed for the correction of deformity of the fifth finger included an elastic wire that provided persistent radial and dorsal traction to assist or restrict of the movement of the fifth finger so that its joints could be exercised actively and passively within the desired range to achieve the therapeutic target (Figure 2H).

In conclusion, the children should undergo systematic functional training for hand rehabilitation as early as possible after experiencing hand burns to actively prevent the occurrence of complications such as stiffness of joints of the hand and tendon adhesions, thereby maximizing the improvement of hand function, reducing the risk of secondary surgery, and improving the quality of life.

This study is the first to analyze and compare the effects of early and late systematic rehabilitation in children with hand burns. However there were limitations in our study because we only analyzed rehabilitation assessment data before and after they received rehabilitation treatment. It was not represent the entire process of contracture progression in burnt hands. Therefore it is better to add the long term effects (such as 6 mo and 1 year from rehabilitation).

In addition, the burnt children might experience psychological problems such as fear, aloneness, depression and anxiety. Our study has already indicated that the early and systemic hand rehabilitation could improve the function of burnt hands. But we don’t know the effects of early rehabilitation on the psychological consequences of burnt children. Future study may pay attention to psychological consequences of these children.

Hypertrophic scar contractures in hand after burn decrease hand function. Rehabilitation in hand can improve the hand activities. But the optimal time of rehabilitation is unclear.

This study was designed to compare the efficacy between early and later rehabilitation in paediatric burnt hands.

This study aimed to investigate the optimal time of rehabilitation in paediatric burnt hands and investigate the relevant factors for the improvement of hand function.

The burnt children were allocated into early (≤ 1 mo from onset) and late (> 1 mo from onset) groups. They received the same rehabilitation treatment. The assessment were performed before and after the treatment.

The children in early group showed more significant improvement than that in late group. The length of rehabilitation time was positively correlated with the hand function improvement.

Early rehabilitation showed better improvement in terms of hand function.

It is suggestion that early rehabilitation intervention can improve the function of burnt hand.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed

Specialty type: Rehabilitation

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Oley MH, Pop TL S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Yin S. Chemical and Common Burns in Children. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2017;56:8S-12S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | McBride JM, Romanowski KS, Sen S, Palmieri TL, Greenhalgh DG. Contact Hand Burns in Children: Still a Major Prevention Need. J Burn Care Res. 2020;41:1000-1003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Barani C, Brosset S, Person H, Guillot M, Braye F, Voulliaume D. [How to treat palmar burn sequelae in children, about 49 cases]. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2021;66:291-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yelvington M, Godleski M, Lee AF, Goverman J, Parry I, Herndon DN, Suman OE, Kowalske K, Holavanahalli R, Gibran NS, Esselman PC, Ryan CM, Schneider JC. Contracture Severity at Hospital Discharge in Children: A Burn Model System Database Study. J Burn Care Res. 2021;42:425-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tan J, Chen J, Zhou J, Song H, Deng H, Ao M, Luo G, Wu J. Joint contractures in severe burn patients with early rehabilitation intervention in one of the largest burn intensive care unit in China: a descriptive analysis. Burns Trauma. 2019;7:17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Li H, Wang S, Tan J, Zhou J, Wu J, Luo G. Epidemiology of pediatric burns in southwest China from 2011 to 2015. Burns. 2017;43:1306-1317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Goverman J, Mathews K, Goldstein R, Holavanahalli R, Kowalske K, Esselman P, Gibran N, Suman O, Herndon D, Ryan CM, Schneider JC. Pediatric Contractures in Burn Injury: A Burn Model System National Database Study. J Burn Care Res. 2017;38:e192-e199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sorkin M, Cholok D, Levi B. Scar Management of the Burned Hand. Hand Clin. 2017;33:305-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Germann G. Hand Reconstruction After Burn Injury: Functional Results. Clin Plast Surg. 2017;44:833-844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Salehi SH, Fatemi MJ, Sedghi M, Niazi M. Effects of early versus delayed excision and grafting on the return of the burned hand function. J Res Med Sci. 2016;21:109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Omar MT, Hegazy FA, Mokashi SP. Influences of purposeful activity versus rote exercise on improving pain and hand function in pediatric burn. Burns. 2012;38:261-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Aghajanzade M, Momeni M, Niazi M, Ghorbani H, Saberi M, Kheirkhah R, Rahbar H, Karimi H. Effectiveness of incorporating occupational therapy in rehabilitation of hand burn patients. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2019;32:147-152. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Plancq MC, Goffinet L, Duquennoy-Martinot V. [Burn child specificity]. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2016;61:568-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Williams T, Berenz T. Postburn Upper Extremity Occupational Therapy. Hand Clin. 2017;33:293-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Meng F, Zuo KJ, Amar-Zifkin A, Baird R, Cugno S, Poenaru D. Pediatric burn contractures in low- and lower middle-income countries: A systematic review of causes and factors affecting outcome. Burns. 2020;46:993-1004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kamolz LP, Kitzinger HB, Karle B, Frey M. The treatment of hand burns. Burns. 2009;35:327-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cowan AC, Stegink-Jansen CW. Rehabilitation of hand burn injuries: current updates. Injury. 2013;44:391-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Richard R, Santos-Lozada AR. Burn Patient Acuity Demographics, Scar Contractures, and Rehabilitation Treatment Time Related to Patient Outcomes: The ACT Study. J Burn Care Res. 2017;38:230-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Fufa DT, Chuang SS, Yang JY. Postburn contractures of the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39:1869-1876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhou R, Qiu L, Xiao J, Mao X, Yuan X. Early wound repair versus later scar repair in children with treadmill hand friction burns. J Burn Care Res. 2021;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Greenhalgh DG. Management of acute burn injuries of the upper extremity in the pediatric population. Hand Clin. 2000;16:175-186, vii. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Feldmann ME, Evans J, O SJ. Early management of the burned pediatric hand. J Craniofac Surg. 2008;19:942-950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |