Published online Aug 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i22.6403

Peer-review started: January 24, 2021

First decision: March 8, 2021

Revised: March 12, 2021

Accepted: May 8, 2021

Article in press: May 8, 2021

Published online: August 6, 2021

Processing time: 184 Days and 12 Hours

Malaria-associated secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is rare. Moreover, the literature on malaria-associated HLH is sparse, and there are no similar cases reported in China.

We report the case of a 29-year-old woman with unexplained intermittent fever who was admitted to our hospital due to an unclear diagnosis. The patient concealed her history of travel to Nigeria before onset. We made a diagnosis of malaria-associated secondary HLH. The treatment strategy for this patient included treatment of the inciting factor (artemether for 9 d followed by artemisinin for 5 d), the use of immunosuppressants (steroids, intravenous immunoglobulin) and supportive care. The patient was discharged in normal physical condition after 25 d of intensive care. No relapses were documented on follow-up at six months and 1 year.

Early diagnosis of the primary disease along with timely intervention and a multidisciplinary approach can help patients achieve a satisfactory outcome.

Core Tip: We found an unexpected association between malaria and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) in this case. Literature on malaria-associated HLH is sparse. There are no similar cases reported in China. In this case, we made the diagnosis based on HLH-2004 criteria and adopted new biomarkers to make the diagnosis of HLH. Through multidisciplinary treatment, the patient was discharged in normal physical condition. This case highlights the importance of early diagnosis and timely therapy of the primary disease to secondary HLH.

- Citation: Zhou X, Duan ML. Malaria-associated secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(22): 6403-6409

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i22/6403.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i22.6403

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a systemic disorder caused by immune dysregulation that occurs in primary and secondary forms. Secondary HLH refers to cases caused by infections, malignancy and autoimmune diseases. HLH secondary to infections can occur with viral, bacterial, fungal or parasitic infections[1]. Malaria is rarely reported to cause HLH. We report the case of a 29-year-old woman with fever, hepatosplenomegaly, pancytopenia, high serum ferritin, hypertriglyceridemia, hypofibrinogenemia and bone marrow hemophagocytosis, consistent with hemophagocytic syndrome. Plasmodium falciparum (P. falciparum) was identified on a peripheral blood smear. Rapid recovery was observed after treatment with antimalarial medications, immunomodulatory therapy and supportive care.

A 29-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital due to intermittent fever for 12 d.

The patient had an unexplained fever (Tmax 41℃), chills and anorexia after a 14 d trip to Sokoto State, Nigeria in September 2018. However, the patient concealed her travel history while visiting the local hospital. She was diagnosed with pneumonia and received antibiotic treatment. With poor response to antibacterial treatment, the patient developed nausea, vomiting, upper abdominal pain, respiratory distress and oliguria. Further investigations showed negativity for Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) DNA but positivity for EBV-IgM. Bone marrow biopsy revealed hemophagocytosis. The patient was suspected to have EBV-related HLH, and was transferred to our hospital for emergency treatment.

The patient had no previous medical history.

No notable personal or family history.

Physical examination revealed blood pressure of 105/64 mmHg, wet rales in the lower lung and upper abdominal tenderness.

Blood tests showed cytopenia, increased liver transaminases, increased bilirubin, hypertriglyceridemia, increased serum ferritin, soluble CD25 (sCD25) level of 21574 pg/mL and negative results for natural killer cell (NK cell) activity. Tests for EBV and cytomegalovirus DNA were negative. There was no evidence of a tumor.

Abdominal ultrasonography and computed tomography (CT) showed splenomegaly (Figure 1).

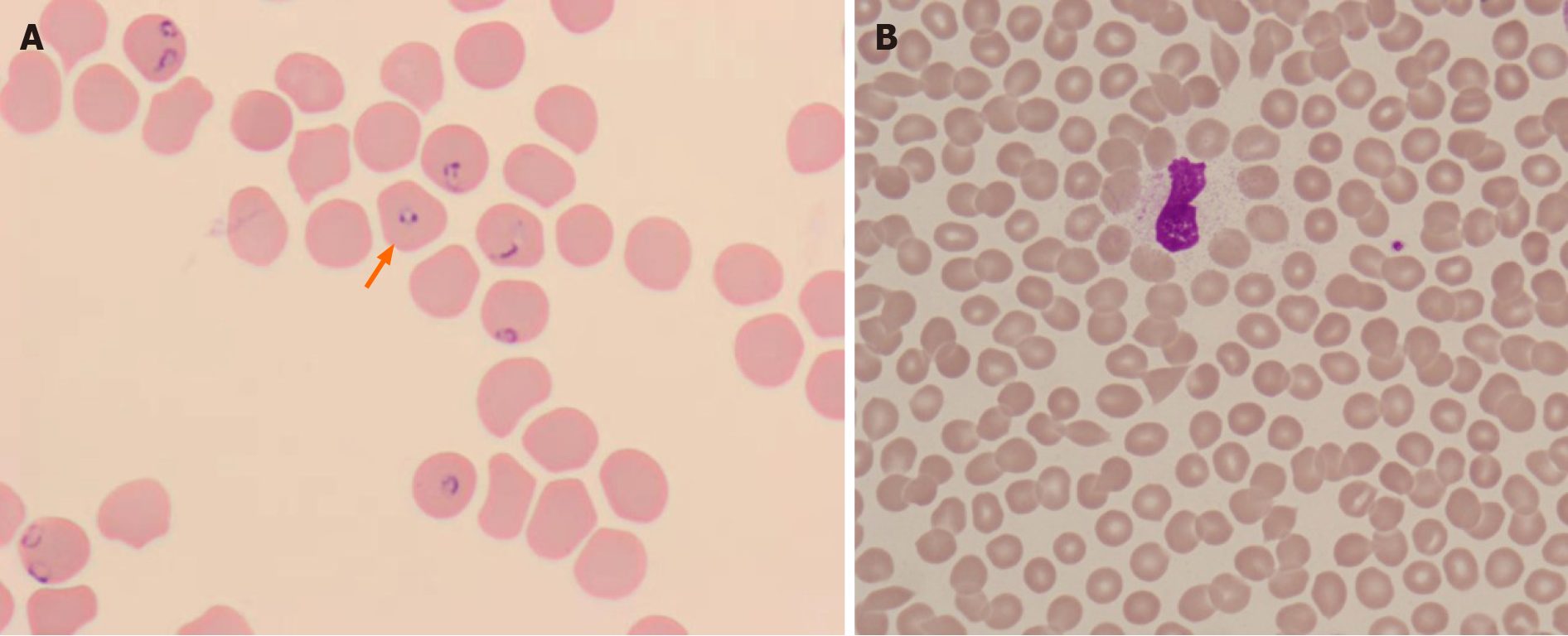

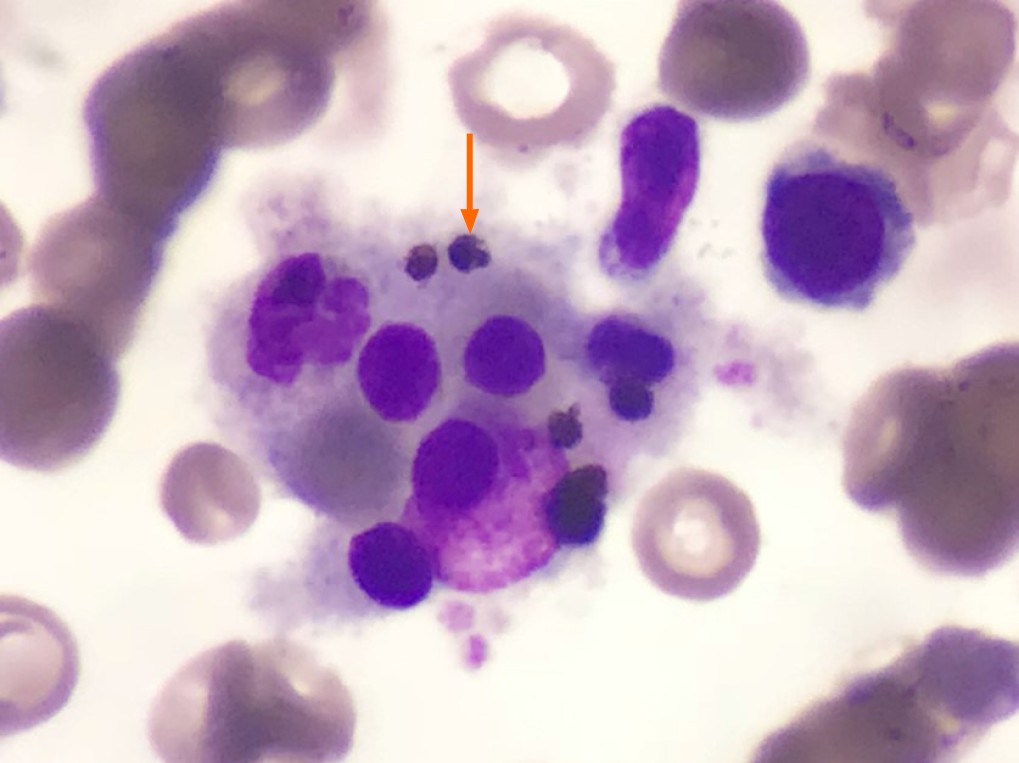

A peripheral blood smear showed P. falciparum (Figure 2A), which was determined to have a 3D7 genotype. Bone marrow aspiration showed the presence of hemophagocytosis (Figure 3)

This patient has a clear diagnosis of malaria and should be treated.

Considering HLH secondary to the malaria, the primary disease should be treated first, and immune-related treatment should be given at the same time.

This patient suffered from multiple organ dysfunction and should be monitored and treated in the Department of Critical Care Medicine.

The final diagnosis in this patient was malaria-associated secondary HLH.

The treatment regimen for malaria included artemether at 80 mg q12 h for 4 d and then 80 mg qd for 5 d, which was changed to dihydroartemisinin and piperaquine phosphate 2 tablets qd for 5 d. At the same time, the patient received methylprednisolone 80 mg qd for 4 d. As we considered the HLH to be secondary to malaria, we treated the primary disease and administered intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) for 5 d (total dose of 2 g/kg).

Subsequently, the patient developed multiorgan dysfunction in critical care medicine. She exhibited acute kidney injury (creatine 569 µmol/L with oliguria), acute liver injury, acute respiratory distress syndrome (PaO2/FiO2 100 mmHg) and coagulopathy and was treated with continuous renal replacement therapy, high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy (HFNC), blood transfusion and nutritional support in the critical care unit. After 7 d of organ support treatment, the patient’s respiratory and renal function recovered to normal, and her liver-enzyme and bilirubin levels decreased.

After 7 d of treatment, no P. falciparum was found in the peripheral blood smear (Figure 2B), and tests for malarial antigens were negative. The patient’s condition improved gradually, and her clinical and laboratory manifestations were normalized (Table 1). She was discharged in normal physical condition after 25 d. No relapses were documented at the six-month and 1-year follow-up.

| Reference range | Before treatment | 7 d after treatment | 14 d after treatment | |

| Temperature (℃) | 36-37 | Tmax 39.8 | No fever | No fever |

| White blood cells (× 109/L) | 3.50-9.50 | 2.88 | 3.78 | 4.33 |

| Neutrophils (× 109/L) | 1.8-6.3 | 1.31 | 2.15 | 2.00 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 115-150 | 49 | 108 | 93 |

| Platelet count (× 109/L) | 125-350 | 50 | 112 | 151 |

| Reticulocytes (× 1012/L) | 0.0140-0.0900 | 0.1443 | 0.2269 | 0.0902 |

| Indirect bilirubin (μmol/L) | 0.00-12.00 | 15.44 | 16.09 | 8.59 |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L) | 0.57-1.70 | 2.45 | 2.42 | 2.23 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 11.00-306.00 | 1989.00 | 1730 | 1516 |

| Fibrinogen (ng/mL) | 1.70-4.00 | 1.41 | 1.31 | 1.63 |

| NK-cell activity | Negative | - | ||

| sCD25 (pg/mL) | 21574 | 4775 | ||

| Spleen ultrasonography | Length 8.5 ± 1.0 cm | 14.2 | - | |

| Thickness 2.8 ± 0.5 cm | 3.8 | 3.4 |

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that is caused by a parasitic protozoan of the genus Plasmodium and has diverse clinical manifestations[2]. The epidemiological history is important for diagnosis. Therefore, we should obtain a thorough and detailed medical history. The diagnosis of malaria was based on a peripheral blood smear and/or rapid diagnostic tests for malarial antigens. Artemisinin is mainly used in the treatment of malaria. Our patient was treated with artemether and dihydroartemisinin because the effect of dihydroartemisinin is 5 times more potent against malaria than artemisinin[3]. She subsequently took oral dihydroartemisinin and piperaquine phosphate. There are also reports of oral doxycycline treatment in the literature.

HLH, a life-threatening disease associated with excessive stimulation of tissue macrophages[4], occurs in primary and secondary forms. Primary HLH is mostly recognized in childhood, whereas the secondary form can occur at any age. Secondary HLH refers to cases caused by infections, malignancy and autoimmune diseases. HLH secondary to infections can occur with viral, bacterial, fungal or parasitic infections; viral infections, especially those caused by EBV, are the most common. The clinical and laboratory manifestations of HLH include fever, splenomegaly, neurologic dysfunction, coagulopathy, liver dysfunction, cytopenia, hypertriglyceridemia, hyperferritinemia, hemophagocytosis, and diminished NK-cell activity. In fact, the clinical manifestations of HLH lack specificity. The severity is related to the levels of immune cell activation and cytokines. Currently, we make the diagnosis based on HLH-2004 criteria[5] (Table 2). Hemophagocytosis cannot be used as a necessary condition to exclude or diagnose HLH. The sensitivity of hemophagocytosis in the diagnosis of HLH is approximately 60%. HLH cannot be excluded in the absence of hemophagocytosis. The sensitivity of ferritin > 500 µg/L in the diagnosis of HLH is 84%. Serum ferritin < 500 µg/L has a negative evaluative significance for the diagnosis of HLH. NK-cell activity is a landmark diagnostic indicator that is irreversible in primary HLH but can be recovered in secondary HLH. The reference range varies depending on the detection method. sCD25 is the most useful marker of inflammation, which reflects the excessive immune activation status of patients. The literature shows that elevated sCD25 in children has a sensitivity of 76.2% and a specificity of 98.2% for the diagnosis of HLH[6]. The treatment strategy for secondary HLH includes supportive care, treatment of inciting factors and the use of immunosuppressants (steroids, IVIG and other immunosuppressive drugs).

| The diagnosis of HLH can be established if either condition 1 or condition 2 below is fulfilled |

| (1) A molecular diagnosis consistent with HLH |

| (2) Diagnostic criteria for HLH fulfilled (five out of the eight criteria below) |

| (A) Initial diagnostic criteria (to be evaluated in all patients with HLH) |

| Fever |

| Splenomegaly |

| Cytopenia (affecting ≥ 2 of 3 lineages in the peripheral blood): |

| Hemoglobin < 90 g/L (in infants < 4 wk: hemoglobin < 100 g/L) |

| Platelets < 100 × 109/L |

| Neutrophils < 1.0 × 109/L |

| Hypertriglyceridemia and/or hypofibrinogenemia: |

| Fasting triglycerides ≥ 3.0 mmol/L (i.e., ≥ 265 mg/dL) |

| Fibrinogen ≤ 1.5 g/L |

| Hemophagocytosis in bone marrow or spleen or lymph nodes |

| No evidence of malignancy |

| (B) New diagnostic criteria |

| Low or absent NK-cell activity (according to local laboratory reference) |

| Ferritin ≥ 500 µg/L |

| Soluble CD25 (i.e., soluble IL-2 receptor) ≥ 2400 U/mL |

Malaria as a cause of secondary HLH is rare. We reviewed the related literature, and fewer than 20 cases have been reported[7-14]. There are no similar cases reported in China. The reason for this is that on the one hand, China is not a malaria-endemic area, and on the other hand, some cases have not been recognized and diagnosed. The types of malarial parasites that cause secondary HLH are P. falciparum and P. vivax[7,13], with P. falciparum accounting for most of these cases. The pathogenesis is not yet clear but may be related to immune dysfunction caused by falciparum malaria. Whether the pathogenic mechanisms of the different types of Plasmodium are different still needs further study.

In this case, the patient had fever and gastrointestinal symptoms, such as fatigue, anorexia, nausea, and vomiting, but no enlarged lymph nodes, rash, bleeding or neurologic dysfunction. Although NK-cell activity was negative, the diagnosis of HLH clearly met seven out of the eight HLH-2004 criteria. However, in most cases reported in the literature, NK-cell activity and sCD25 antigen levels were not available. Thanks to the new diagnostic markers, the patient was timely diagnosed. In addition, intensive care unit intervention played a valuable role in the patient’s recovery. No deaths due to malaria-associated HLH have been reported. Our patient also had a good prognosis.

In conclusion, malaria-associated secondary HLH is rare. If the patient has fever, splenomegaly and an elevated ferritin level, HLH should be highly suspected, and relevant examinations should be conducted. Early diagnosis of the primary disease along with timely intervention and a multidisciplinary approach can help patients achieve a satisfactory outcome.

The authors express special thanks to Dr. Wang Lei and Dr. Jia-Ning Chen, who guided this work.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Critical care medicine

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Vyshka G S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, López-Guillermo A, Khamashta MA, Bosch X. Adult haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet. 2014;383:1503-1516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 788] [Cited by in RCA: 962] [Article Influence: 87.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Weeratunga P, Rathnayake G, Sivashangar A, Karunanayake P, Gnanathasan A, Chang T. Plasmodium falciparum and Mycoplasma pneumoniae co-infection presenting with cerebral malaria manifesting orofacial dyskinesia and haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Malar J. 2016;15:461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zhang H, Zhou F, Wang Y, Xie H, Luo S, Meng L, Su B, Ye Y, Wu K, Xu Y, Gong X. Eliminating Radiation Resistance of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer by Dihydroartemisinin Through Abrogating Immunity Escaping and Promoting Radiation Sensitivity by Inhibiting PD-L1 Expression. Front Oncol. 2020;10:595466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Klein E, Ronez E. Peripheral hemophagocytosis in malaria infection. Blood. 2012;119:910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, Imashuku S, Ladisch S, McClain K, Webb D, Winiarski J, Janka G. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:124-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3075] [Cited by in RCA: 3602] [Article Influence: 200.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Wang Y, Liu D, Zhu G, Yin C, Sheng G, Zhao X. [Significance of soluble CD163 and soluble CD25 in diagnosis and treatment of children with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis]. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2015;53:824-829. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Bhagat M, Kanhere S, Kadakia Affiliation When The Manuscript Was Written Department Of Paediatrics K J Somaiya Medical College And Hospital Mumbai India P, Phadke V, George R, Chaudhari K. Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: a cause of unresponsive malaria in a 5-year-old girl. Paediatr Int Child Health. 2014;2046905514Y0000000163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Amireh S, Shaaban H, Guron G. Severe Plasmodium vivax cerebral malaria complicated by hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis treated with artesunate and doxycycline. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2018;11:34-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bae E, Jang S, Park CJ, Chi HS. Plasmodium vivax malaria-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in a young man with pancytopenia and fever. Ann Hematol. 2011;90:491-492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Santos JA, Neves JF, Venâncio P, Gouveia C, Varandas L. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis secondary to Falciparum malaria in a 5 year-old boy. Ann Hematol. 2015;94:161-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Selvarajan D, Sundaravel S, Alagusundaramoorthy SS, Jacob A. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with concurrent malarial infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Harioly Nirina MOM, Raheritiana TM, Harioly Nirina MOJ, Rasolonjatovo AS, Rakoto Alson AO, Rasamindrakotroka A. [Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis associated with Plasmodium falciparum]. Med Mal Infect. 2017;47:569-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Niang A, Niang SE, Ka el HF, Ka MM, Diouf B. Collapsing glomerulopathy and haemophagocytic syndrome related to malaria: a case report. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:3359-3361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Vinoth PN, Thomas KA, Selvan SM, Suman DF, Scott JX. Hemophagocytic syndrome associated with Plasmodium falciparum infection. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2011;54:594-596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |