Published online Aug 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i22.6244

Peer-review started: January 12, 2021

First decision: April 29, 2021

Revised: May 7, 2021

Accepted: June 3, 2021

Article in press: June 3, 2021

Published online: August 6, 2021

Processing time: 196 Days and 14.9 Hours

The etiology of Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) with intussusception remains undefined.

To investigate the risk factors for intussusception in children with HSP and gastrointestinal (GI) involvement.

Sixty children with HSP and concomitant intussusception admitted to the Beijing Children’s Hospital of Capital Medical University between January 2006 and December 2018 were enrolled in this study. One hundred pediatric patients with HSP and GI involvement but without intussusception, admitted to the same hospital during the same period, were randomly selected as a control group. The baseline clinical characteristics of all patients, including sex, age of onset, duration of disease, clinical manifestations, laboratory test results, and treatments provided, were assessed. Univariate and multiple logistic regression analyses were performed to identify possible risk factors.

The 60 children in the intussusception group comprised 27 girls (45%) and 33 boys (55%) and the 100 children in the non-intussusception group comprised 62 girls (62%) and 38 boys (38%). The median age of all patients were 6 years and 5 mo. Univariate and multiple regression analyses revealed age at onset, not receiving glucocorticoid therapy within 72 h of emergence of GI symptoms, hematochezia, and D-dimer levels as independent risk factors for intussusception in children with HSP (P < 0.05).

The four independent risk factors for intussusception in pediatric HSP with GI involvement would be a reference for early prevention and treatment of this potentially fatal disease.

Core Tip: Intussusception has an incidence of about 5% in Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP), and is a common cause of acute surgical abdomen in the affected children. There is limited research on risk factors for intussusception in children with HSP. Age at onset below 6 years, not receiving glucocorticoid therapy within 72 h of onset of gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, hematochezia, and increased D-dimer levels are independent risk factors for intussusception in children with HSP and GI involvement.

- Citation: Zhao Q, Yang Y, He SW, Wang XT, Liu C. Risk factors for intussusception in children with Henoch-Schönlein purpura: A case-control study. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(22): 6244-6253

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i22/6244.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i22.6244

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP), a common leukocytoclastic vasculitis involving the capillaries and arterioles, is mediated by immune complexes[1]. HSP is one of the most common childhood vasculitides, and approximately two thirds of children with HSP have gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms[2]. Children with HSP and GI involvement may exhibit concomitant acute abdominal symptoms, including GI bleeding, intussusception, intestinal obstruction, intestinal necrosis, intestinal perforation, pancreatitis, and appendicitis, all of which require surgical intervention[3]. Severe GI involvement may be fatal and associated with renal involvement[4].

Few reports have assessed HSP and concomitant intussusception in children. However, it was reported that the typical age of onset of intussusception in HSP with GI involvement is about 6 years old, which is much older than that of primary intussusception (4–12 mo)[5]. Meanwhile, it is known that intussusception has an incidence of about 5% in HSP cases, and represents the most common reason for acute surgical abdomen in these children[6]. Intussusception can be fatal if not diagnosed and treated in a timely manner[7].

However, few reports have assessed the etiology of intussusception in children with HSP due to its low clinical incidence. In particular, the risk factors for intussusception in children with HSP are largely unknown. Therefore, the aim of this study was to identify risk factors for the development of intussusception in children with HSP. We found that age at onset below 6 years, not receiving glucocorticoid therapy within 72 h of onset of GI symptoms, hematochezia, and high Ddimer levels independently predict intussusception in pediatric HSP with GI involvement. These data may serve as a reference for early prevention and treatment of this potentially fatal disease.

This retrospective study assessed patients with HSP and concomitant intussusception admitted to the Beijing Children's Hospital of Capital Medical University between January 2006 and December 2018. Meanwhile, individuals with HSP and GI involvement but without intussusception, admitted to the same hospital during the same period, were randomly selected as a control group.

The inclusion criteria were: (1) Age from 1 to 17 years old; and (2) Diagnosis of HSP and GI symptoms. The exclusion criterion were: (1) Incomplete clinical data; and (2) Patients with severe heart, brain, liver, kidney, lung, and hematopoietic system diseases.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Beijing Children's Hospital, Capital Medical University, China (approval number IEC-C-008-A08-V.05.1). The requirement for informed consent was waived because of the retrospective nature of the research and data anonymity.

The baseline clinical characteristics of all patients with HSP, including sex, age at onset, disease duration, clinical manifestations, laboratory test results, treatments, and follow-up duration, were collected.

Intussusception refers to the intussusception or retraction into the lumen of a segment of the intestine[8]. In this case, the related mesentery is pulled and compressed in the varus segment, resulting in congestion and edema, which causes a series of clinical symptoms. Intussusception is the second most common acute abdominal ailment in children after appendicitis[9]. The typical triad of intussusception includes abdominal pain, vomiting, and bloody stools, occurring in less than half of cases[7]. In case of clinical suspicion of intussusception, abdominal ultrasound should be performed for confirmation. The sensitivity and specificity of abdominal ultrasound in the diagnosis of intussusception are 100% and 80%-100%, respectively[9].

All patients with HSP met the diagnostic criteria jointly developed in 2010 by European League Against Rheumatism and Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organization[10]. Abdominal ultrasonography in a patient with concomitant intussusception revealed typical “concentric ring signs” or “sleeve” like changes suggestive of intussusception. GI involvement in HSP was defined as the presence of any of the following findings: Acute diffuse abdominal pain, intussusception, and GI bleeding.

Normally distributed continuous data are expressed as the mean ± SD, and non-normally distributed ones are expressed as median and interquartile ranges (Q1 and Q3). Categorical data are expressed as n (%). Categorical variables were compared by the Chi-square test. Variables with P < 0.05 in univariate analysis were entered into stepwise multiple logistic regression analysis. Results are expressed as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and P values, for each model. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 22.0 (IBM corporation, Armonk, NY, United States). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

There were a total 160 children with HSG and GI involvement in this study. The 60 children in the intussusception group comprised 27 girls (45%) and 33 boys (55%); the 100 children in the non-intussusception group comprised 62 girls (62%) and 38 boys (38%). The mean age of patients in this study was 6.6 ± 2.0 years old, and the age at disease onset was 6 years and 5 mo, ranging from 2.5 to 12 years old. Disease durations were 0.5-54.0 d (median of 5.0 d). One hundred and thirty-seven (85.7%) patients were experiencing a first episode of HSP. No patient in this cohort had a history of intussusception.

At baseline, there were statistically significant between-group differences in age at onset (P < 0.001), disease duration (P = 0.02), first disease episode status (P = 0.017), and whether glucocorticoid therapy was received within 72 h of emergence of GI symptoms (P < 0.001). There were no statistically significant between-group differences in sex distribution or GI tract malformation rate (P > 0.05; Table 1).

| Variable | Intussusception group (n = 60) | Non-intussusception group (n = 100) | P value |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.383 | ||

| Male | 33 (55.0) | 62 (62.0) | |

| Female | 27 (45.0) | 38 (38.0) | |

| Age at onset, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| < 6 yr | 27 (45.0) | 9 (9.0) | |

| ≥ 6 yr | 33 (55.0) | 91 (91.0) | |

| Duration of disease (d), n (%) | 0.02 | ||

| ≤ 28 | 58 (96.7) | 85 (85.0) | |

| > 28 | 2 (3.3) | 15 (15.0) | |

| First episode, n (%) | 0.017 | ||

| Yes | 57 (95.0) | 80 (80.0) | |

| No | 3 (5.0) | 20 (20.0) | |

| GI tract malformation, n (%) | 0.117 | ||

| Yes | 3 (5.0) | 1 (1.0) | |

| No | 57 (95.0) | 99 (99.0) | |

| Receiving glucocorticoid therapy within 72 h of GI symptom emergence, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 20 (33.3) | 77 (77.0) | |

| No | 40 (66.7) | 23 (23.0) | |

| Vomiting, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 39 (65.0) | 27 (27.0) | |

| No | 21 (35.0) | 73 (73.0) | |

| Hematemesis, n (%) | 0.204 | ||

| Yes | 7 (11.7) | 6 (6.0) | |

| No | 53 (88.3) | 94 (94.0) | |

| Hematochezia, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 33 (55.0) | 14 (14.0) | |

| No | 27 (45.0) | 86 (86.0) | |

| White blood cell count, n (%) | 0.014 | ||

| < 10.0 × 109/L | 21 (35.0) | 55 (55.0) | |

| ≥ 10.0 × 109/L | 39 (65.0) | 45 (45.0) | |

| Neutrophil count, n (%) | 0.085 | ||

| < 10.0 × 109/L | 32 (53.3) | 67 (67.0) | |

| ≥ 10.0 × 109/L | 28 (46.3) | 33 (33.0) | |

| Platelet count, n (%) | 0.168 | ||

| < 300.0 × 109/L | 11 (18.3) | 28 (28.0) | |

| ≥ 300.0 × 109/L | 49 (81.7) | 72 (72.0) | |

| C-reactive protein level, n (%) | 0.072 | ||

| ≤ 8 mg/L | 26 (43.3) | 58 (58.0) | |

| > 8 mg/L | 34 (56.7) | 42 (42.0) | |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, n (%) | 0.388 | ||

| ≤ 15 mm/h | 50 (83.3) | 73 (73.0) | |

| > 15 mm/h | 10 (16.7) | 27 (27.0) | |

| D-dimer level, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| < 1 mg/L | 7 (11.7) | 70 (70.0) | |

| ≥ 1 mg/L | 53 (88.3) | 30 (30.0) |

Regarding symptoms, statistically significant differences were observed in vomiting and hematochezia rates between the two groups (P < 0.001), whereas hematemesis rates were not significantly different (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

Clinical tests showed a statistically significant difference in white blood cell count (P = 0.014) and D-dimer levels (P < 0.001) between the study groups, but not in neutrophil count, platelet count, C-reactive protein levels, or erythrocyte sedimen

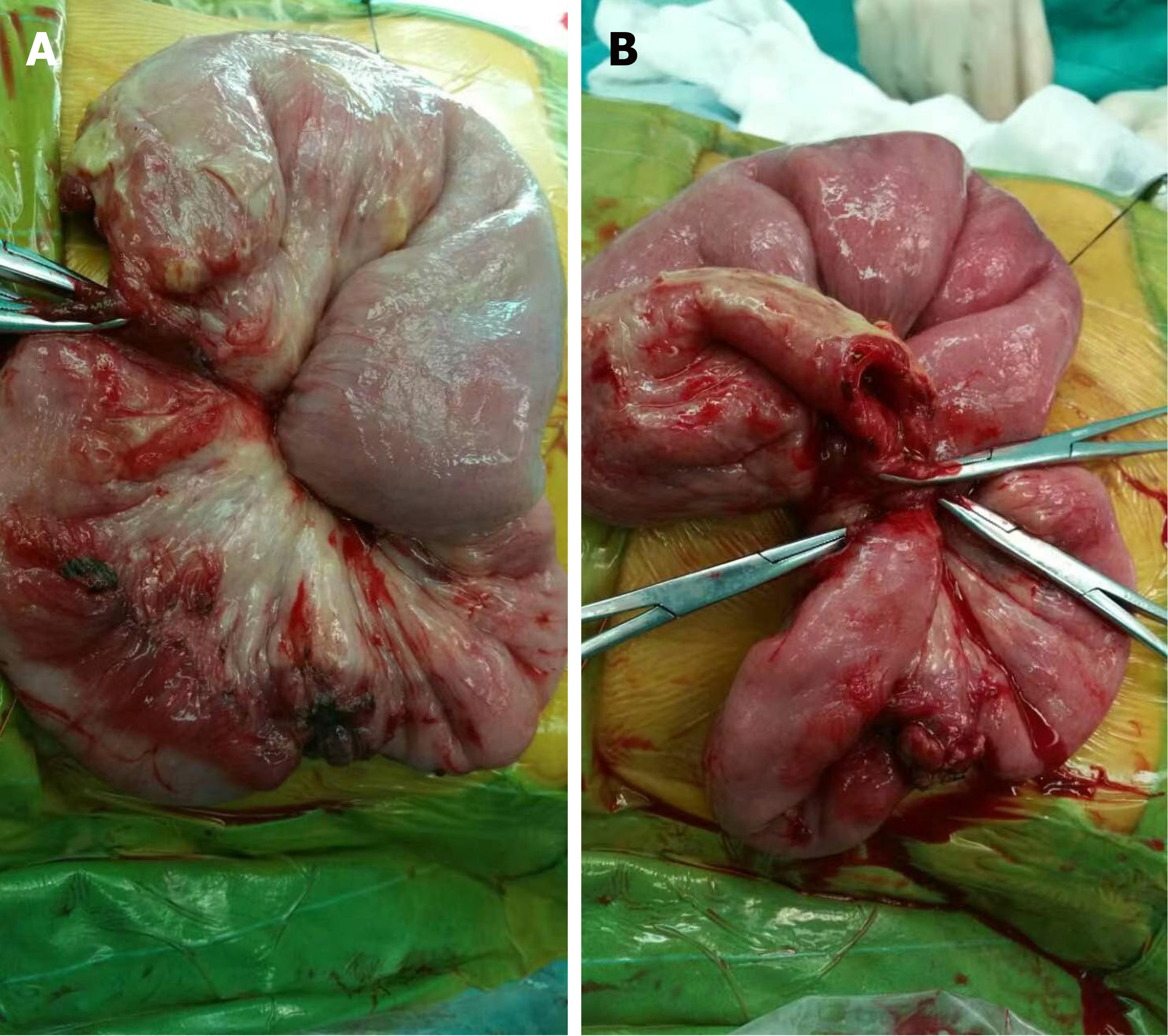

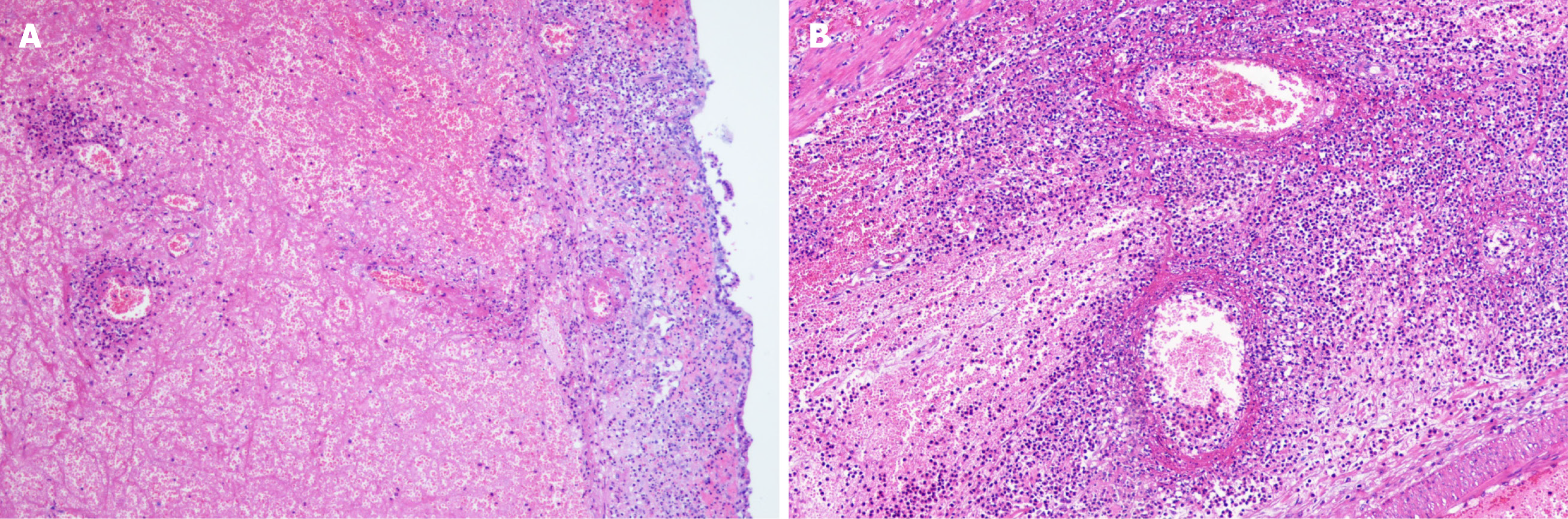

Eight (13.3%) individuals had intussusception reduction via air enema (one was small intestine intussusception, and the rest were ileum colon intussusception), and the rest of 48 (80.0%) patients underwent surgery. The surgeries performed were bowel resection (n = 18) and manual reduction (n = 30). The median of nested distance in intussusception was 11 cm (range, 4-40 cm), and the median of nested diameter in intussusception was 5.0 cm (range, 1.8-8.0 cm). Small bowel intussusception was the predominant type observed during surgery (n = 29, 60.4%) and the rest 19 (39.6%) patients had ileocolic intussusception. Among the surgically treated patients, intestinal necrosis (n = 18, 37.5%), intestinal perforation (n = 2, 4.2%), and appendicitis (n = 7, 14.6%) were identified. Among them, three patients were underwent appendectomy. All the 18 cases with enterectomy had their intestinal tissue samples sent for pathological biopsy (Figure 1). Pathological results mainly showed full-thickness congestion, hemorrhage, necrosis of the intestinal wall, fibrinoid necrosis of small vessel wall, and neutrophil infiltrate on the wall and around the small vessel. Some parts of the mucosal lamina propria and submucosa were highly edema. The lamina propria and submucosa were infiltrated by acute and chronic inflammatory cells, such as sheet neutrophils, eosinophils, and plasma cells (Figure 2).

Eight factors with P < 0.05 in univariate analysis were included in the logistic regression equation. Stepwise multiple regression analysis was performed to analyze risk factors for intussusception in children with HSP. The results showed that hematochezia (OR = 5.355, 95%CI = 1.809-15.852, P = 0.002), D-dimer levels (OR = 7.193, 95%CI = 2.507-20.640, P < 0.001), glucocorticoid therapy timing (OR = 0.342, 95%CI = 0.127-0.920, P = 0.034), and age at disease onset (OR = 0.202, 95%CI = 0.065-0.632, P = 0.006) were indepen

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

| OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Age at onset | 0.121 | 0.052-0.284 | < 0.001 | 0.202 | 0.065-0.632 | 0.006 |

| First episode | 4.750 | 1.347-16.748 | 0.015 | 6.705 | 0.840-53.537 | 0.073 |

| Duration of disease | 0.195 | 0.043-0.887 | 0.034 | 0.208 | 0.018-2.382 | 0.207 |

| Glucocorticoid therapy within 72 h | 0.149 | 0.073-0.304 | < 0.001 | 0.342 | 0.127-0. 920 | 0.034 |

| Vomiting | 5.021 | 2.518-10.012 | < 0.001 | 2.138 | 0.795-5.749 | 0.132 |

| Hematochezia | 7.508 | 3.511-16.056 | < 0.001 | 5.355 | 1.809-15.852 | 0.002 |

| White blood cell count | 2.270 | 1.172-4.395 | 0.015 | 1.217 | 0.440-3.363 | 0.705 |

| D-dimer level | 17.667 | 7.206-43.313 | < 0.001 | 7.193 | 2.507-20.640 | < 0.001 |

The etiology of HSP accompanied by intussusception remains largely unclear, although it can lead to high mortality. The present study clearly demonstrated that age at onset below 6 years, not receiving glucocorticoid therapy within 72 h of onset of GI symptoms, hematochezia, and high Ddimer levels independently predict intussusception in pediatric HSP with GI involvement.

As shown above, median age at disease onset was 6 years and 5 mo, which is consistent with previous findings[4]. In addition, logistic regression analysis suggested that age at disease onset below 6 years was an independent risk factor for intussusception in children with HSP. This finding corroborates a previous study reporting that age under 7 years was the most common onset age in HSP with concomitant intussusception[4]. HSP tends to occur at 4-6 years of age[11,12], and children with HSP at younger ages may have more serious clinical process[13], which may be related to the fact that HSP children under 6 years of age are more prone to intussusception.

The present study also showed that hematochezia was an independent risk factor for the development of intussusception in children with HSP (OR = 5.355). This may be related to disease pathogenesis. Indeed, the current prevailing view is that submucosal bleeding and intestinal wall edema are the starting points of the mechanism underlying the development of HSP with GI involvement and concomitant intussusception in children[14]. Vasculitis involving capillaries and arterioles in the GI tract causes segmental bleeding from the subserosa and mucosa. Meanwhile, extensive edema of the intestinal mucosa, enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes, GI dysfunction, irregular peristalsis, and GI tract spasm lead to intussusception[15]. It is admitted that GI bleeding is more common in pediatric cases of HSP with GI involvement and intestinal perforation[16]. Furthermore, GI bleeding is a key factor in prolonged hospital stay in children with HSP[17]. In pediatric HSP patients with GI involvement, hematochezia and abdominal pain should be assessed as possible reasons for acute surgical abdomen. However, HSP with GI involvement often lacks specific clinical manifestations. Therefore, few children in the above intussusception group exhibited differential signs requiring surgical treatment, including abdominal mass, rebound tenderness, and hypoactive bowel sounds. It is necessary to perform abdominal color Doppler ultrasound imaging to screen for surgical complications.

D-dimer is a specific degradation product resulting from the hydrolysis of fibrinogen into fibrin monomer by thrombin, followed by crosslinking with activated factor XII and plasmin hydrolysis[18]. D-dimer plays an important role in the human coagulation system[19]. HSP is primarily caused by sub-endothelial deposition of immune complexes, leading to vascular endothelial cell damage, followed by coagulation system activation and microthrombosis[18]. This induces the fibrinolytic system and increases D-dimer levels. Recent studies have shown that serum D-dimer levels are significantly higher in children with HSP compared with healthy controls[19]. It was also shown that D-dimer levels reflect the severity of HSP, especially the extent of GI damage[20]. Furthermore, D-dimer levels are more closely related to HSP symptoms in children than other general inflammatory parameters such as white blood cell count and C-reactive protein level[21]. The present study revealed high D-dimer levels as an independent risk factor for intussusception in children with HSP, which is consistent with the above reports (OR = 7.193). Whether D-dimer can be used as a prognostic marker in children with HSP requires further investigation in large-scale clinical trials.

Different from classical intussusception in the ileocecum[22], the most common type of intussusception in HSP was ileal intussusception (51%), followed by ileocolic intussusception (39%), and other types were rare[23]. In the present study, of 48 children with intussusception treated by operation, small intussusception was found in 29 (60.4%) cases, which was consistent with the reports in the literature. It was considered that the intestinal involvement of abdominal type HSP was the most common. This is because the small intestine is the main part of digestion and absorption, the contact area with chyme or related irritants is the widest, and the distribution of capillaries is abundant. The submucosa of the small intestine not only forms a capillary network between the intestinal glands, but also forms a capillary network close to the epithelium in the intestinal villi. The submucosa of the stomach and large intestine only forms a capillary network between the glands, so the small intestine is more involved than the colon.

Intussusception is the most common acute abdomen of HSP, and its surgical treatment includes air enema, water enema, and surgical treatment. Because the secondary changes such as edema and bleeding of the intestinal wall in children with HSP are serious, the success rate of air enema is relatively low. In the present study, the success rate of air enema was only 13.3% in 60 patient and 48 cases underwent surgical treatment. And there were intestinal necrosis in 18 cases, intestinal perforation in 2, and enterectomy in 16 Because HSP is a self-limited disease, it is feasible to diagnose early and avoid unnecessary surgery. However, in the process of conservative treatment, experienced surgical teams are needed to closely observe the changes of patients' conditions. There was a view[24] that for older children or adults, surgery should be carried out as soon as possible to avoid delay in treatment. For patients with intussusception, the most serious complication of conservative treatment is intestinal perforation. Once there are signs of intestinal ischemic necrosis and intestinal perforation, surgical treatment is needed. For patients with short intussusception and good intestinal condition, simple manual reduction can be performed. If intestinal viability is suspected during surgery, enterostomy is recommended to avoid iatrogenic intestinal perforation.

Many studies have shown that glucocorticoid therapy is beneficial for shortening the duration of abdominal pain, and reducing the risk of development of intussusception and the need for surgical intervention[25]. However, the value of glucocorticoids in the treatment of HSP remains controversial[26]. Studies have suggested that glucocorticoids increase the risk of GI ulcers, bleeding, and even perforation[16]. As shown above, no glucocorticoid therapy within 72 h of emergence of GI symptoms was an independent risk factor for intussusception in children with HSP and GI involvement (OR = 0.342). The regression coefficient was negative, supporting the viewpoint that early application of glucocorticoid therapy in HSP with GI involvement is beneficial to intussusception prevention. However, the clinical dosage and duration of glucocorticoids in HSP are not standardized. Further clinical studies are required to standardize this treatment and avoid the associated adverse effects. To the best of our knowledge, surgical resection is always the first choice for the treatment of adult intussusception to avoid the accident of intestinal perforation[27]. However, no unified clinical treatment standard for intussusception is currently available in children, and there is no clinical or imaging evidence to suspect that intussusception in children with perforation and peritonitis could be treated by enema reduction. However, it is reported that 58% of intussusception cases in children with HSP occurred in the small intestine[26], which may lead to a low success rate of enema reduction, and make most of them still need surgical treatment.

This study had several limitations. First, it was a retrospective study, with inherent shortcomings. In addition, the sample size was very limited, and all patients were from the same institution. Furthermore, multiple potential risk factors were not investigated in detail, including the nature of stool blood (e.g., bloody, black, and tarry, or only positive for occult blood) and the exact glucocorticoid dosage. Therefore, large multicenter studies investigating the associations of the above factors with abdominal intussusception in children with HSP in greater depth are warranted.

In summary, age at onset below 6 years, not receiving glucocorticoid therapy within 72 h of onset of GI symptoms, hematochezia, and increased D-dimer levels are independent risk factors for intussusception in children with HSP with GI involvement. Caution is needed in children suffering from HSP with GI involvement and showing at least one of the abovementioned factors, to avoid further disease aggravation and intussusception.

The incidence rate of intussusception in Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) is about 5%. It is the most common surgical acute abdomen in children with HSP. However, few reports have assessed the etiology of intussusception in children with HSP due to low clinical incidence. In particular, the risk factors for intussusception in children with HSP are largely unknown.

The aim of this study was to identify risk factors for the development of intussusception in children with HSP and gastrointestinal (GI) involvement.

The aim of this study was to identify risk factors for the development of intussusception in children with HSP and GI involvement.

Sixty children with HSP and intussusception who were hospitalized at Beijing Children's Hospital Affiliated to Capital Medical University from January 2006 to December 2018 were selected. One hundred cases of abdominal HSP without intussusception at Beijing Children's Hospital during the same period were randomly selected as a control group. The general clinical data of all HSP patients were investigated, including gender, age of onset, onset time, clinical symptoms and signs, laboratory examination, imaging manifestations, treatment measures, etc. Univariate and multiple logistic regression analyses were performed to identify possible risk factors.

The 60 children in the intussusception group included 27 girls (45%) and 33 boys (55%), while 100 children in the non-intussusception group included 62 girls (62%) and 38 boys (38%). The median age was 6 years and 5 mo. Univariate and multivariate regression analyses showed that age of onset, failure to receive glucocorticoid treatment within 72 h after GI symptoms, hematochezia, and D-dimer levels were independent risk factors for intussusception in children with HSP (P < 0.05).

Age at onset below 6 years, not receiving glucocorticoid therapy within 72 h of onset of GI symptoms, hematochezia, and increased D-dimer levels are independent risk factors for intussusception in children with HSP with GI involvement. Caution is needed in children suffering from HSP with GI involvement and showing at least one of the abovementioned factors, to avoid further disease aggravation and intussusception.

In view of the above factors, it is necessary to conduct a large sample multicenter study.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Yamamoto T S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Yang YH, Tsai IJ, Chang CJ, Chuang YH, Hsu HY, Chiang BL. The interaction between circulating complement proteins and cutaneous microvascular endothelial cells in the development of childhood Henoch-Schönlein Purpura. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0120411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mrusek S, Krüger M, Greiner P, Kleinschmidt M, Brandis M, Ehl S. Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Lancet. 2004;363:1116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ebert EC. Gastrointestinal manifestations of Henoch-Schonlein Purpura. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:2011-2019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Karadağ ŞG, Tanatar A, Sönmez HE, Çakmak F, Kıyak A, Yavuz S, Çakan M, Ayaz NA. The clinical spectrum of Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children: a single-center study. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38:1707-1714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Acar B, Arikan FI, Alioglu B, Oner N, Dallar Y. Successful treatment of gastrointestinal involvement in Henoch-Schönlein purpura with plasmapheresis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008;23:2103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jasić M, Subat-Dezulović M, Nikolić H, Jonjić N, Manestar K, Dezulović M. Henoch-Schönlein purpura complicated by appendicitis, intussusception and ureteritis. Coll Antropol. 2011;35:197-201. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Menon P, Singh S, Ahuja N, Winter TA. Gastrointestinal manifestations of Henoch-Schoenlein purpura. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:42-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bines JE, Kohl KS, Forster J, Zanardi LR, Davis RL, Hansen J, Murphy TM, Music S, Niu M, Varricchio F, Vermeer P, Wong EJ; Brighton Collaboration Intussusception Working Group. Acute intussusception in infants and children as an adverse event following immunization: case definition and guidelines of data collection, analysis, and presentation. Vaccine. 2004;22:569-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Applegate KE. Intussusception in children: evidence-based diagnosis and treatment. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39 Suppl 2:S140-S143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, Funovits J, Felson DT, Bingham CO 3rd, Birnbaum NS, Burmester GR, Bykerk VP, Cohen MD, Combe B, Costenbader KH, Dougados M, Emery P, Ferraccioli G, Hazes JM, Hobbs K, Huizinga TW, Kavanaugh A, Kay J, Kvien TK, Laing T, Mease P, Ménard HA, Moreland LW, Naden RL, Pincus T, Smolen JS, Stanislawska-Biernat E, Symmons D, Tak PP, Upchurch KS, Vencovský J, Wolfe F, Hawker G. 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:2569-2581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6830] [Cited by in RCA: 6224] [Article Influence: 414.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ekinci RMK, Balci S, Melek E, Karabay Bayazit A, Dogruel D, Altintas DU, Yilmaz M. Clinical manifestations and outcomes of 420 children with Henoch Schönlein Purpura from a single referral center from Turkey: A three-year experience. Mod Rheumatol. 2020;30:1039-1046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Okubo Y, Nochioka K, Sakakibara H, Hataya H, Terakawa T, Testa M, Sundel RP. Nationwide epidemiological survey of childhood IgA vasculitis associated hospitalization in the USA. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35:2749-2756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shim JO, Han K, Park S, Kim GH, Ko JS, Chung JY. Ten-year Nationwide Population-based Survey on the Characteristics of Children with Henoch-Schӧnlein Purpura in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2018;33:e174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lim CJ, Chen JH, Chen WL, Shen YS, Huang CC. Jejunojejunum intussusception as the single initial manifestation of Henoch-Schönlein purpura in a teenager. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30:2085.e1-2085.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cui XH, Liu H, Fu L, Zhang C, Wang XD. Henoch-Schönlein purpura with intussusception and hematochezia in an adult: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e16981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yavuz H, Arslan A. Henoch-Schönlein purpura-related intestinal perforation: a steroid complication? Pediatr Int. 2001;43:423-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Uehara E, Nagata C, Masuda H, Fujimori K, Kobayashi S, Kubota M, Ishiguro A. Risk factors of long hospital stay for immunoglobulin A vasculitis: Single-center study. Pediatr Int. 2018;60:918-922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mir S, Yavascan O, Mutlubas F, Yeniay B, Sonmez F. Clinical outcome in children with Henoch-Schönlein nephritis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007;22:64-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Purevdorj N, Mu Y, Gu Y, Zheng F, Wang R, Yu J, Sun X. Clinical significance of the serum biomarker index detection in children with Henoch-Schonlein purpura. Clin Biochem. 2018;52:167-170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Yilmaz D, Kavakli K, Ozkayin N. The elevated markers of hypercoagulability in children with Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2005;22:41-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hong J, Yang HR. Laboratory markers indicating gastrointestinal involvement of henoch-schönlein purpura in children. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2015;18:39-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wei CH, Fu YW, Wang NL, Du YC, Sheu JC. Laparoscopy vs open surgery for idiopathic intussusception in children. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:668-672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Shimoyama T, Matsuda N, Kurobe M, Hayakawa T, Nishioka M, Shimohira M, Takasawa K. Colonoscopic diagnosis and reduction of recurrent intussusception owing to Henoch-Schönlein purpura without purpura. Paediatr Int Child Health. 2019;39:219-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lai HC. Henoch-Schönlein purpura with intussusception: a case report. Pediatr Neonatol. 2010;51:65-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ronkainen J, Koskimies O, Ala-Houhala M, Antikainen M, Merenmies J, Rajantie J, Ormälä T, Turtinen J, Nuutinen M. Early prednisone therapy in Henoch-Schönlein purpura: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Pediatr. 2006;149:241-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Bluman J, Goldman RD. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children: limited benefit of corticosteroids. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:1007-1010. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Potts J, Al Samaraee A, El-Hakeem A. Small bowel intussusception in adults. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2014;96:11-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |