Published online Jul 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i20.5526

Peer-review started: November 4, 2020

First decision: December 21, 2020

Revised: December 23, 2020

Accepted: March 11, 2021

Article in press: March 11, 2021

Published online: July 16, 2021

Processing time: 240 Days and 20.2 Hours

Comitant esotropia is the most common form of strabismus. It is caused by heterogeneous environmental and genetic risk factors. The pure duplication of the long arm of chromosome 19 is a rare abnormality. Only 8 patients with partial trisomy of the long arm of chromosome 19q have been reported to date. Here, we describe a girl with pure duplication of 19q, who was diagnosed with congenital esotropia, microcephaly, and gallbladder agenesis.

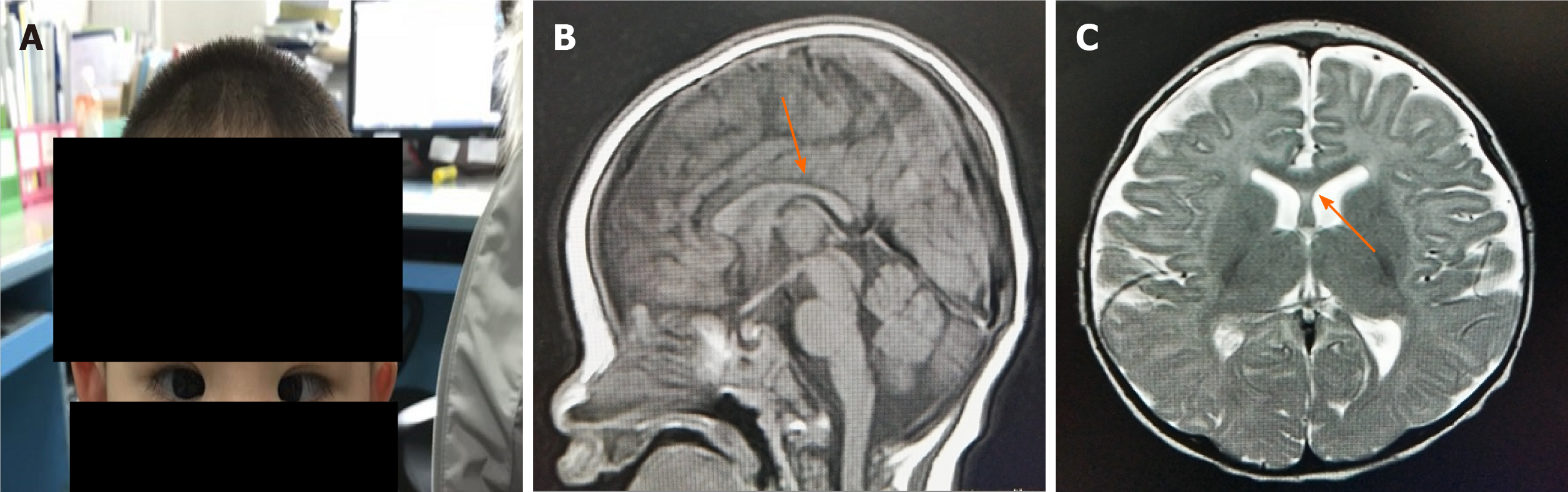

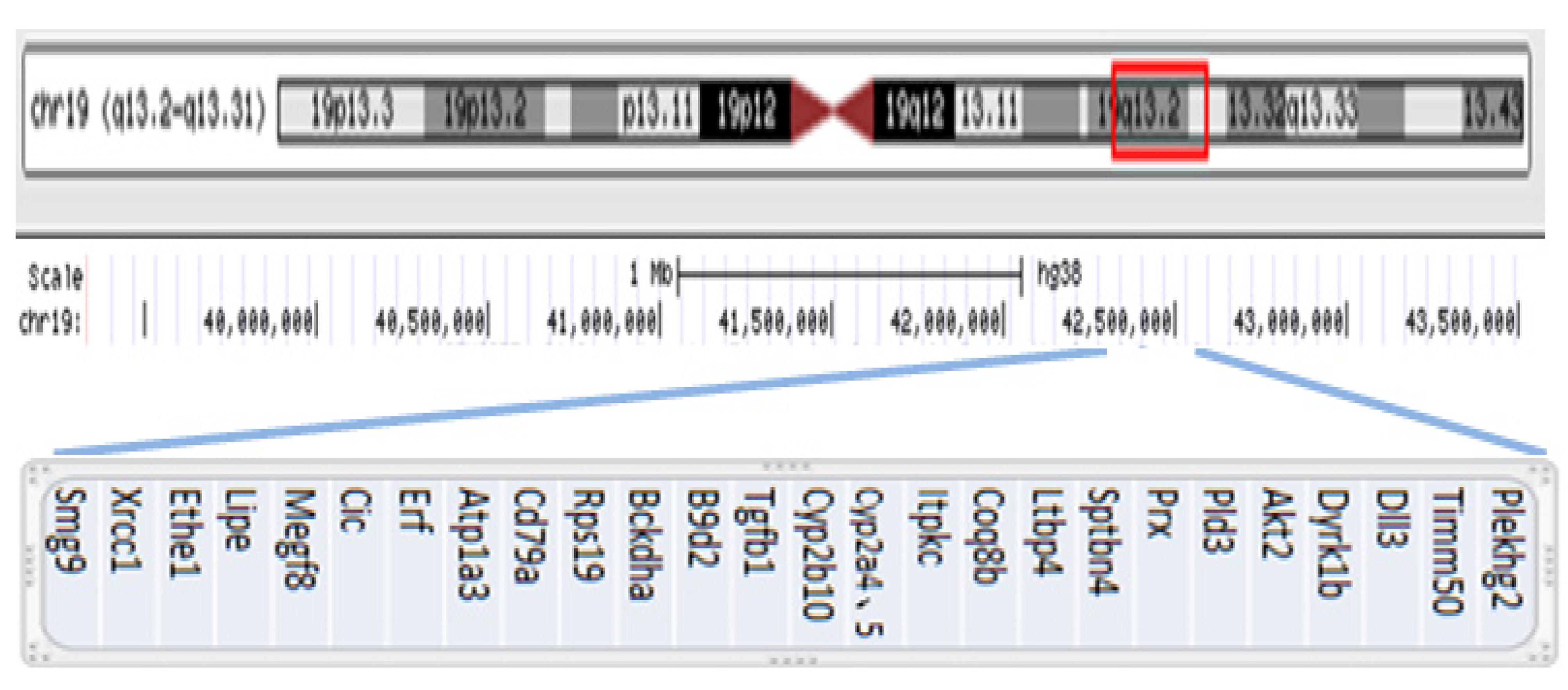

The patient was diagnosed with esotropia when she was 1-year-old. The Krimsky method showed +50 prism diopters in the primary gaze position. No additional abnormal findings were observed following slit lamp and fundus examination, but the features of the full-field electroretinogram showed a decreased amplitude and increased implicit times. Magnetic resonance imaging showed ventriculomegaly with thinning of the corpus callosum and splenium in her brain. A 4.42 Mb mosaic duplication within 19q13.2-q13.31 region (chr19:39,343,725 to 43,762,586) was detected by microarray comparative genomic hybridization.

Strabismus is reported in many live borns with pure duplication of 19q. This important clinical characteristic indicates that the candidate genes fundamental for this phenotype may be narrowed to genes within the 19q13.3-q13.31 region. There were two candidate genes observed that may contribute to the comitant esotropia phenotype, namely XRCC1 (19:43,543,311) and SMG9 (19:43,727,991).

Core Tip: The pure duplication of 19q is a rare chromosome abnormality that may affect a number of genes. Patients with 19q abnormality show a complicated syndrome such as developmental delay, dysmorphic features, and clinical nurse specialist malformations. To date, only 8 patients with partial trisomy of 19q have been reported. Here, we describe a girl with pure duplication of 19q, who was diagnosed with congenital esotropia, microcephaly, and gallbladder agenesis.

- Citation: Feng YL, Li ND. Duplication of 19q (13.2-13.31) associated with comitant esotropia: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(20): 5526-5534

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i20/5526.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i20.5526

Comitant esotropia is a very common form of childhood strabismus with a prevalence of approximately 2.5% among White populations of European ancestry and 0.5% among Africans and Asians[1]. It is frequently noted in infancy or early childhood as the angle of esotropia misalignment between the two eyes remains relatively constant with changes in gaze direction. Comitant esotropia is often accompanied by amblyopia (uniocular visual neglect), a leading cause of visual impairment in children and young adults.

The pathogenesis of comitant esotropia remains largely unknown. Although many studies based on family trio and twins have demonstrated a genetic contribution to strabismus[2-5], there are limited data supporting Mendelian segregation. Parikh et al[6] reported the results of linkage analysis in a large family with non-syndromic strabismus with presumed autosomal recessive inheritance, which has been identified as the first susceptibility locus on chromosome 7p22.1[6]. Another study on 55 Japanese families including at least two members with comitant strabismus revealed that the loci at chromosomes 4q28.3 and 7q31.2 showed a significant evidence of linkage[7], which focuses on the chromosomal loci down to WNT2 and MGST2[8]. Beyond this, the genetic contributions to comitant strabismus remain undefined.

Duplication of 19q is a rare chromosome abnormality that may affect a number of genes. To date, only 8 patients with partial trisomy of 19q have been reported[9-16] (Table 1). We found that strabismus was present in some of these cases, indicating that the pathogenic genes fundamental for the strabismus phenotype might be associated with chromosome 19q duplications.

| Present case | Hall et al[9] | Bhat et al[10] | Qorri et al[11] | Palomares et al[12] | Quack et al[13] | Zung et al[14] | Lugli et al[15] | Rim et al[16] | |

| Sex | F | M | M | F | F | M | M | M | M |

| Age | 18 mo | 5 yr | 18 mo | 27 mo | 15 mo | 3 yr | 14 yr | 36 mo | 5 yr |

| Dup (19) | Mos q13.2q13.32 | Mos q13.11q13.2 | q13.3q13.4 | q13.1q13.3 | q12q13.2 | q11.05q13.2 | q12q13.2 | q12q13.2 | 19q13.32 |

| Developmental delay | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Growth retardation | + | - | + | - | - | - | - | - | + |

| Craniofacial findings | Microcephaly, esotropia | Macrocephaly | Microcephaly, strabismus | Slightly higher palate | Microcephaly, strabismus | Macrocephaly | Macrocephaly | - | Microcephaly |

| Heart | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | + | - |

| Genitourinary and gastrointestinal findings | Gallbladder agenesis | Bilateral urinary reflux | Bilateral inguinal hernia | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Brain | Thinning of the corpus callosum, Bilateral ventricle dilation | Corpus callosumagenesis | - | - | Thinning of the corpus callosum and splenium | - | Cortical atrophy agenesis of the corpus callosum | + | - |

| Seizures | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | + | - |

| Skeletal | Hypotonia | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Visual/auditive findings | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Other | - | - | - | Crease between the 1st and 2nd toe | Hypotonia | Obese | Obese | - | - |

| Method | aCGH, FISH | aCGH | FISH | FISH | CGH | FISH | CGH | FISH, CGH | aCGH |

We present a girl with 19q duplication (13.2-13.31), who was diagnosed with microcephaly, comitant esotropia, developmental delay, and gallbladder agenesis. We used conventional G-band karyotyping and array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) to explore the potential correlation between the phenotype and the genetic disorder.

An 18-mo girl accompanied by her father and mother, presented to the Ophthalmology Department in August 2018. Her parents complained about her strabismus for more than 6 mo (Figure 1A).

The parents complained about her strabismus.

The patient was born at 39 wk as the first fetus of her healthy, non-consanguineous parents and was delivered via Cesarean section. When she was born, the Apgar score was 6 at 1 min and 8 at 5 min. She was diagnosed with microcephaly and developmental delay because her body weight, length, and head circumference were 2140 g (3rd percentile), 43 cm (3rd percentile), and 30 cm (25th percentile), respectively. She was also found to have gallbladder agenesis upon B-scanning ultrasonic examination.

The absence of this duplication in her parents involved in the chromosomal and aCGH analyses indicated that the 4.42 Mb duplication was a de novo rearrangement in this affected patient.

The Krimsky method showed +50 prism diopters in the primary gaze position. Cycloplegic refraction showed +3.50 D sph in the right eye and +3.25 D sph in the left eye. No additional abnormal findings were observed following slit lamp and fundus examination, but the features of the full-field electroretinogram (FF-ERG) showed a decreased amplitude and increased implicit times.

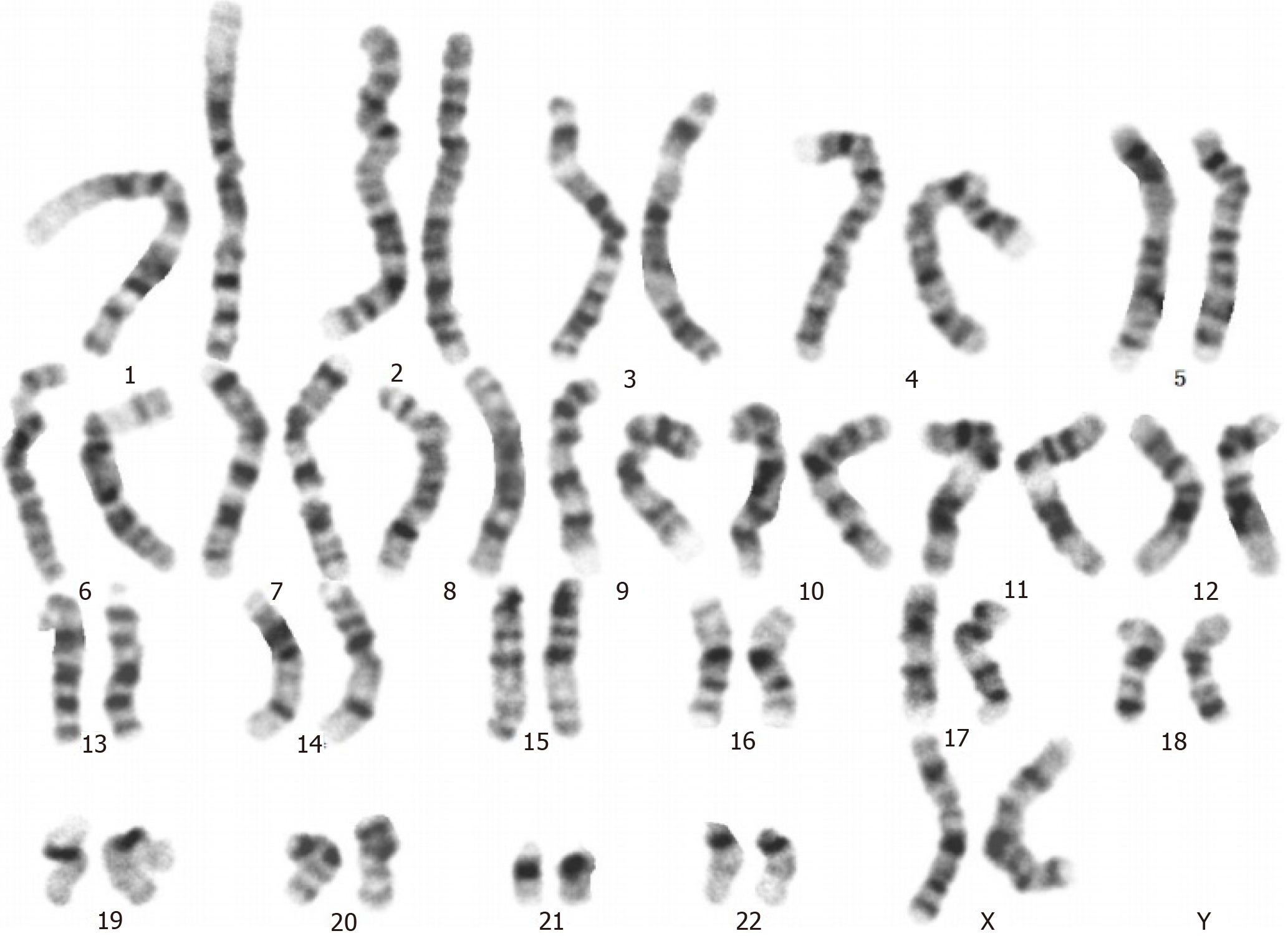

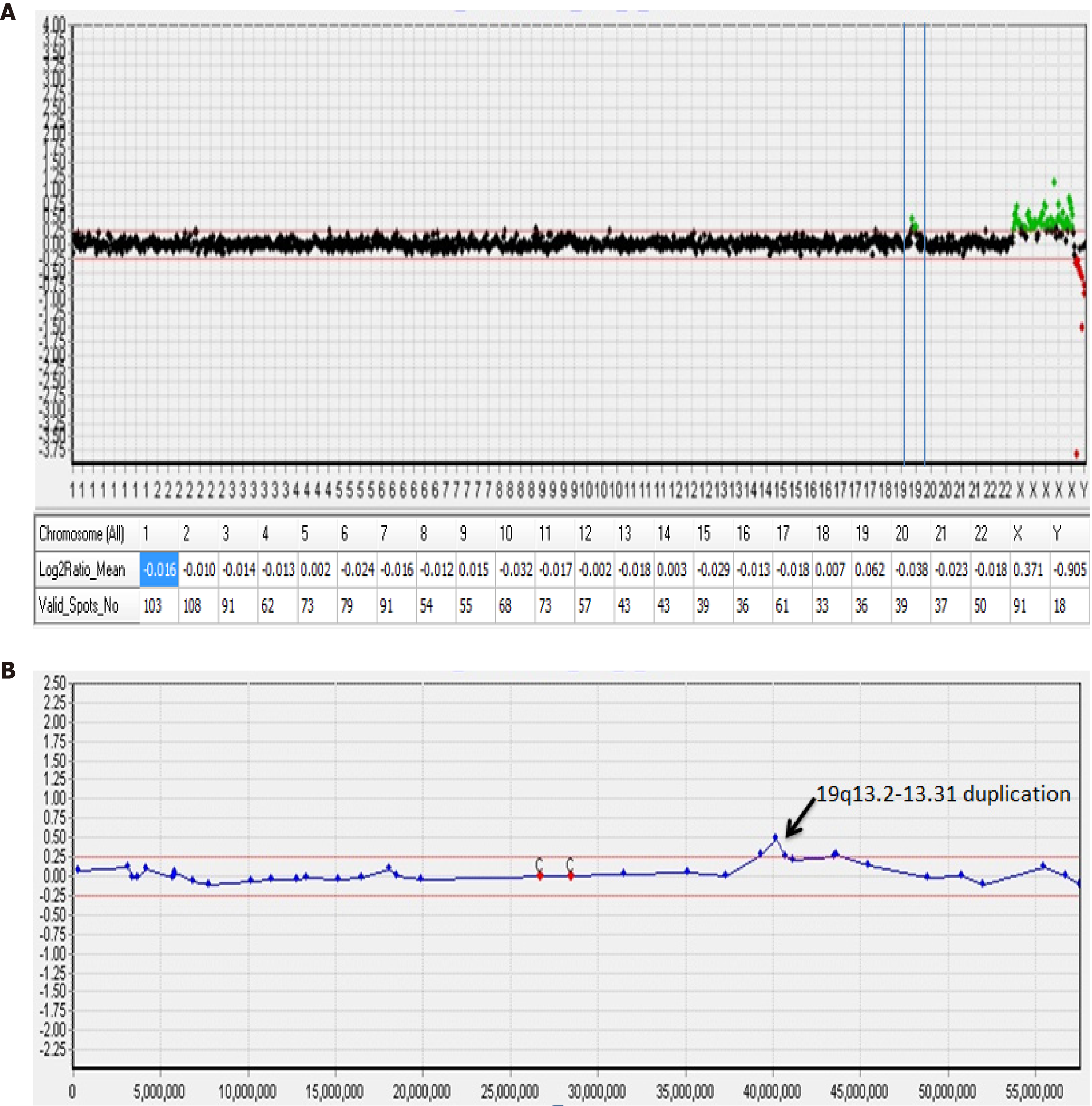

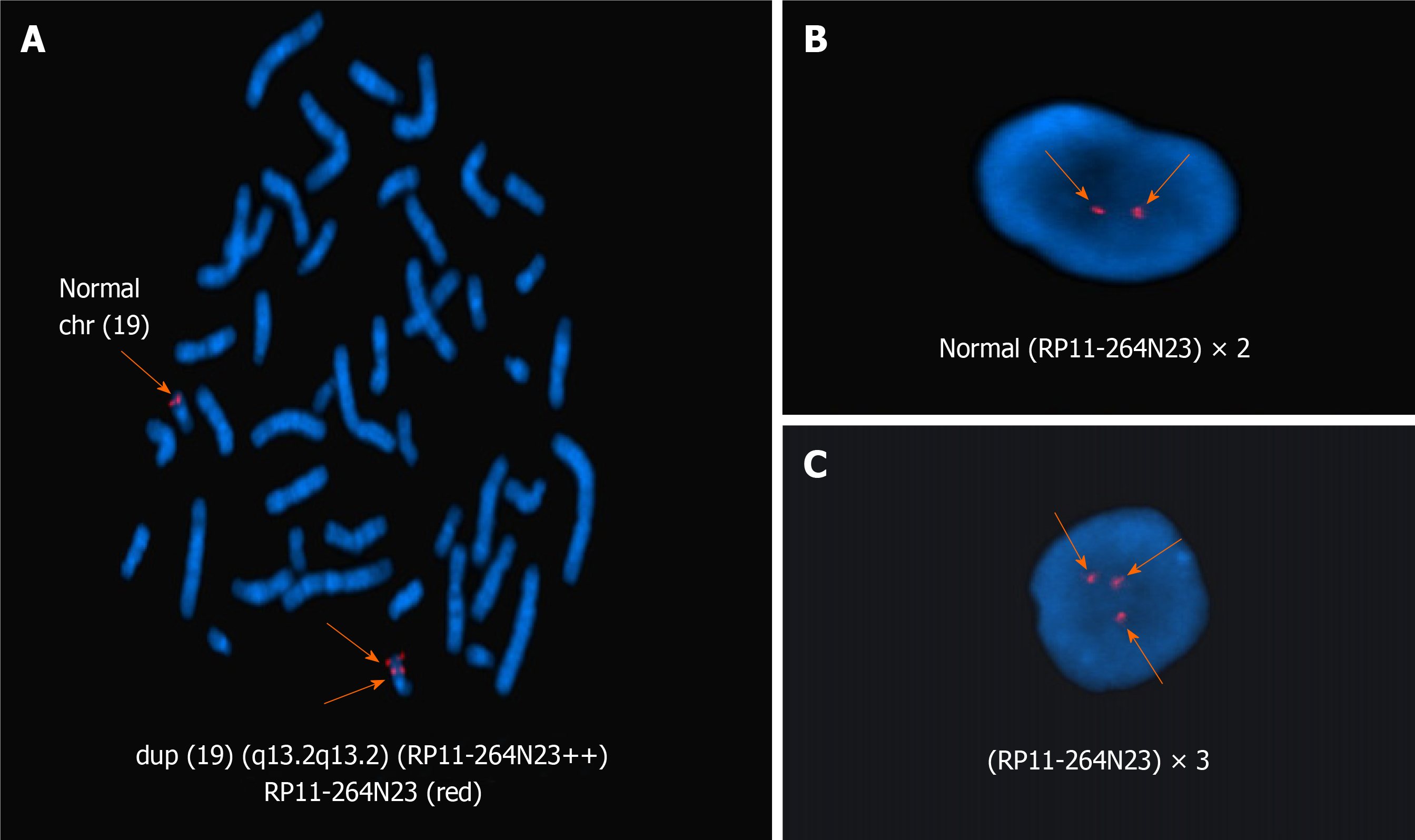

A normal karyotype (46, XX) was revealed at the 550-band resolution using the conventional G-band karyotyping with her peripheral blood (Figure 2). However, a 4.42-Mb mosaic duplication within the 19q13.2–q13.31 region (chr19:39,343,725 to 43,762,586 ) was detected by aCGH (MACArray Karyo 1440 BAC-chip; Macrogen, Seoul, Korea) (Figure 3), which was further confirmed by fluorescence in situ hybridization using the RP11-264N23 (19q13.2) probes (Empire Genomics LLC, Buffalo, NY, United States) on both interphase and metaphase spreads presenting a mosaic ratio of 92% (46 cells) in 50 examined cells and only 8% (4 cells) with a normal karyotype (Figure 4). The absence of this duplication in her parents involved in the chromosomal and aCGH analyses indicated that the 4.42 Mb duplication was a de novo rearrangement in this affected patient.

The final diagnosis of the presented case was congenital esotropia, microcephaly, and gallbladder agenesis.

She underwent bilateral medial rectus recession of 6.0 mm at the age of 18 mo. Forced duction tests were performed intraoperatively and showed no mechanical force or restriction of the extraocular muscles.

Her postoperative measurement was 10Δ esotropia (Krimsky) after 1 mo. Extraocular muscles movement were normal.

Pure duplications of 19q are rare, and as previously reported in the literature, only 8 cases were live born. To our knowledge, the patient described in this study is the second confirmed case of mosaicism involving duplication of the 19q region. In 2010, Hall et al[9] reported the first case of mosaic trisomy in 19q13.11q13.2 with obesity, macrocephaly, and global developmental delay. Psychomotor or mental retardation is a common feature in these live borns. In addition, microcephaly was described in 3 of 8 cases[9,13,16]. Three patients had alterations in the corpus callosum[9,12,14], consistent with our case. The duplication region 19q13.2–13.31 in this case contained 27 OMIM Morbid genes (Figure 5), but only Plekhg2 is currently known to have a phenotype associated with leukodystrophy and acquired microcephaly. Edvardson et al[17] reported 5 children from two unrelated consanguineous Palestinian families with a severe neurodevelopmental disorder. The children presented in infancy with delayed psychomotor development, hypotonia, and postnatal progressive microcephaly. Brain imaging of all patients showed a similar pattern of abnormal white matter, consistent with leukodystrophy. Finally, it was inferred that abnormality of pleckstrin homology domain containing, family G member 2 expression might cause microcephaly, abnormal white matter, and developmental delay. Thus, it is not surprising that our patient presented with those clinical features, and our findings evidently further confirm the genotypic and phenotypic links of this gene abnormality[18,19].

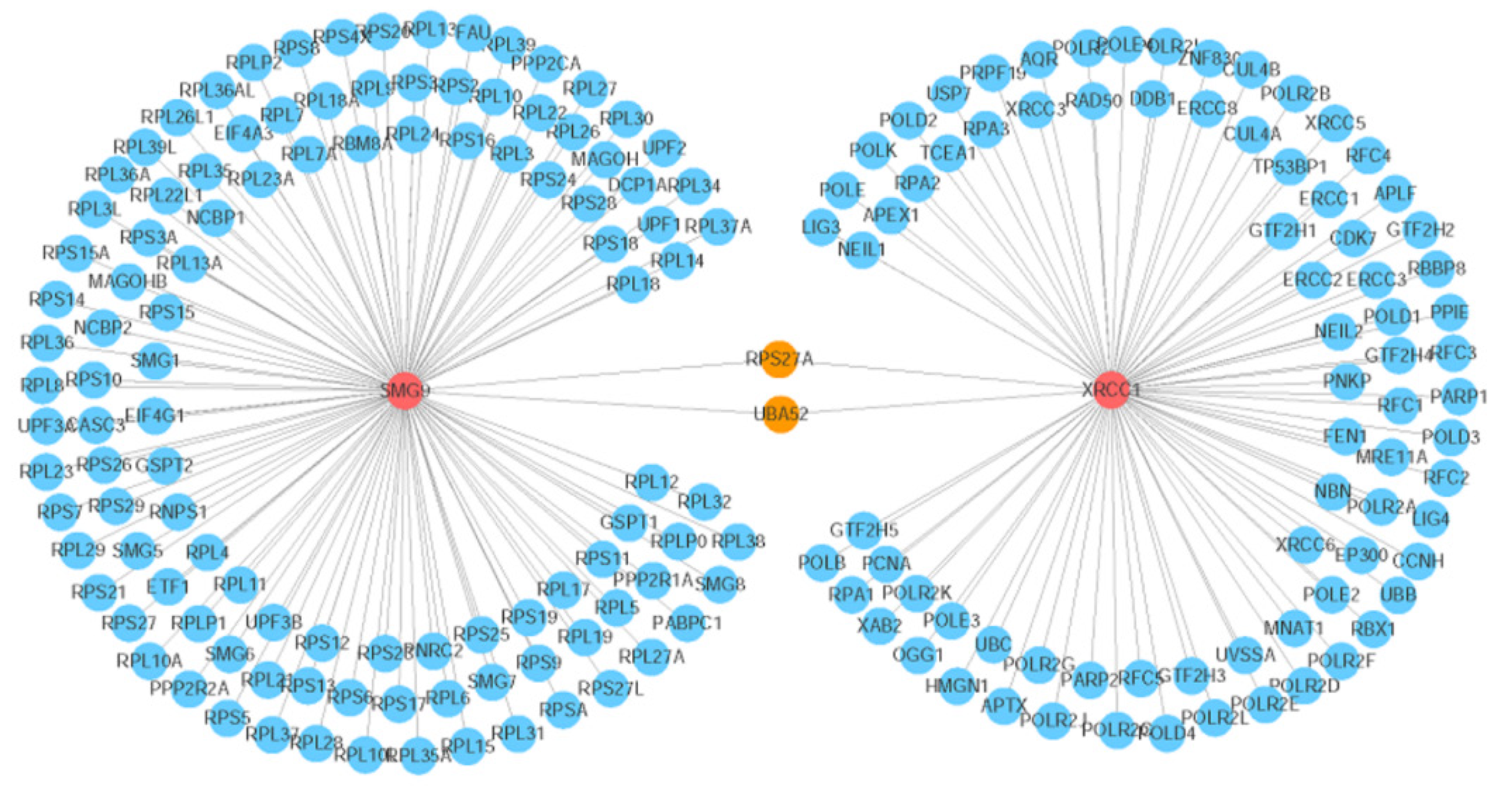

Comitant esotropia is another special feature that was described in 3 of these live born. Bhat et al[10] reported the first case of small de novo duplication of 19q (13.3-13.4) with comitant esotropia, and our patient was also found to have esotropia in 19q (13.2-13.31). These important clinical characteristics may indicate that the candidate genes fundamental for these phenotypes could be narrowed to the genes within the 19q13.3-q13.31 region. There were two candidate genes observed that may contribute to the comitant esotropia phenotype, XRCC1 (19:43,543,311) and SMG9 (19:43,727,991). XRCC1 is a molecular scaffold protein that assembles multiprotein complexes involved in DNA single-strand break repair[10]. The XRCC1 protein complexes are important for normal neurological function. Hoch et al[20] showed that biallelic mutations in human XRCC1 were associated with ocular motor apraxia, axonal neuropathy, and progressive cerebellar ataxia. The SMG9 gene encodes an essential component of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Shaheen et al[21] reported two unrelated consanguineous families of Arab origin in which 5 patients had a heart and brain malformation syndrome, including hypertelorism, small eyes, and poor vision. Further analyses of the gene network showed that two genes (ubiquitin A-52 and ribosomal protein S27A) can either interact with XRCC1 or SMG9, which are important candidates associated with comitant esotropia, suggesting the potential roles of their interactions during eye development (Figure 6).

Although it is still unclear how the copy number change affects the actions of XRCC1 and SMG9 or their interactions, the genetic evidence shows that these two genes are associated with eye development, and the possible duplication may determine an overexpression of some or all of these genes, leading to an imbalanced eye development.

To conclude, the present patient provides further support for a distinct 19q duplication phenotype comprising developmental delay, microcephaly, thinning of the corpus callosum, and esotropia. The other phenotypic features are more variable, such as gallbladder agenesis and the moderately subnormal results of the FF-ERG stimulus threshold testing, which were not observed in previous case reports. There is a possibility that mosaicism may, in itself, cause the phenotype rather than the sole effect of 19q anomalies. Clinical evaluation of additional patients will be required to further delineate this phenotype.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Noviello C, Sugimura H S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Lin S, Li FJ, Wang LH. [Comparative measurements of exodeviations in intermittent exotropia]. Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi. 2013;49:609-614. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Chia A, Lin X, Dirani M, Gazzard G, Ramamurthy D, Quah BL, Chang B, Ling Y, Leo SW, Wong TY, Saw SM. Risk factors for strabismus and amblyopia in young Singapore Chinese children. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2013;20:138-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Paul TO, Hardage LK. The heritability of strabismus. Ophthalmic Genet. 1994;15:1-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wilmer JB, Backus BT. Genetic and environmental contributions to strabismus and phoria: evidence from twins. Vision Res. 2009;49:2485-2493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Matsuo T, Hayashi M, Fujiwara H, Yamane T, Ohtsuki H. Concordance of strabismic phenotypes in monozygotic vs multizygotic twins and other multiple births. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2002;46:59-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Parikh V, Shugart YY, Doheny KF, Zhang J, Li L, Williams J, Hayden D, Craig B, Capo H, Chamblee D, Chen C, Collins M, Dankner S, Fiergang D, Guyton D, Hunter D, Hutcheon M, Keys M, Morrison N, Munoz M, Parks M, Plotsky D, Protzko E, Repka MX, Sarubbi M, Schnall B, Siatkowski RM, Traboulsi E, Waeltermann J, Nathans J. A strabismus susceptibility locus on chromosome 7p. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:12283-12288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shaaban S, Matsuo T, Fujiwara H, Itoshima E, Furuse T, Hasebe S, Zhang Q, Ott J, Ohtsuki H. Chromosomes 4q28.3 and 7q31.2 as new susceptibility loci for comitant strabismus. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:654-661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhang J, Matsuo T. MGST2 and WNT2 are candidate genes for comitant strabismus susceptibility in Japanese patients. PeerJ. 2017;5:e3935. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hall CE, Cunningham JJ, Hislop RG, Berg JN. A boy with supernumerary mosaic trisomy 19q, involving 19q13.11-19q13.2, with macrocephaly, obesity and mild facial dysmorphism. Clin Dysmorphol. 2010;19:218-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bhat M, Morrison PJ, Getty A, McManus D, Tubman R, Nevin NC. First clinical case of small de novo duplication of 19q (13.3-13.4) confirmed by FISH. Am J Med Genet. 2000;91:201-203. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Qorri M, Oei P, Dockery H, McGaughran J. A rare case of a de novo dup(19q) associated with a mild phenotype. J Med Genet. 2002;39:E61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Palomares Bralo M, Delicado A, Lapunzina P, Velázquez Fragua R, Villa O, Angeles Mori M, Luisa de Torres M, Fernández L, Pérez Jurado LA, López Pajares I. Direct tandem duplication in chromosome 19q characterized by array CGH. Eur J Med Genet. 2008;51:257-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Quack B, Van Roy N, Verschraegen-Spae MR, Klein F. Interstitial deletion and ring chromosome derived from 19q. Proximal 19q trisomy phenotype. Ann Genet. 1992;35:241-244. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Zung A, Rienstein S, Rosensaft J, Aviram-Goldring A, Zadik Z. Proximal 19q trisomy: a new syndrome of morbid obesity and mental retardation. Horm Res. 2007;67:105-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lugli L, Malacarne M, Cavani S, Pierluigi M, Ferrari F, Percesepe A. A 12.4 Mb direct duplication in 19q12-q13 in a boy with cardiac and CNS malformations and developmental delay. J Appl Genet. 2011;52:335-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rim JH, Kim JA, Yoo J. A Novel 1.13 Mb Interstitial Duplication at 19q13.32 Causing Developmental Delay and Microcephaly in a Pediatric Patient: the First Asian Case Reports. Yonsei Med J. 2017;58:1241-1244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Edvardson S, Wang H, Dor T, Atawneh O, Yaacov B, Gartner J, Cinnamon Y, Chen S, Elpeleg O. Microcephaly-dystonia due to mutated PLEKHG2 with impaired actin polymerization. Neurogenetics. 2016;17:25-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Caldecott KW. Single-strand break repair and genetic disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:619-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 802] [Cited by in RCA: 731] [Article Influence: 43.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Caldecott KW. XRCC1 and DNA strand break repair. DNA Repair (Amst). 2003;2:955-969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 446] [Cited by in RCA: 466] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hoch NC, Hanzlikova H, Rulten SL, Tétreault M, Komulainen E, Ju L, Hornyak P, Zeng Z, Gittens W, Rey SA, Staras K, Mancini GM, McKinnon PJ, Wang ZQ, Wagner JD; Care4Rare Canada Consortium; Yoon G, Caldecott KW. XRCC1 mutation is associated with PARP1 hyperactivation and cerebellar ataxia. Nature. 2017;541:87-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 25.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Shaheen R, Anazi S, Ben-Omran T, Seidahmed MZ, Caddle LB, Palmer K, Ali R, Alshidi T, Hagos S, Goodwin L, Hashem M, Wakil SM, Abouelhoda M, Colak D, Murray SA, Alkuraya FS. Mutations in SMG9, Encoding an Essential Component of Nonsense-Mediated Decay Machinery, Cause a Multiple Congenital Anomaly Syndrome in Humans and Mice. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98:643-652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |