Published online Jun 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i17.4294

Peer-review started: January 14, 2021

First decision: March 8, 2021

Revised: March 16, 2021

Accepted: April 20, 2021

Article in press: April 20, 2021

Published online: June 16, 2021

Processing time: 132 Days and 5.1 Hours

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) during pregnancy is rare, especially in twin pregnancy, and it can endanger the lives of the mother and children. Except for conventional cardiovascular risk factors, pregnancy and assisted reproduction can increase the risk of AMI during pregnancy. AMI develops secondary to different etiologies, such as coronary spasm and spontaneous coronary artery dissection.

A 33-year-old woman, with twin pregnancy in the 31st week of gestation, presented to the hospital with intermittent chest tightness for 12 wk, aggravation for 1 wk, and chest pain for 4 h. Combined with the electrocardiogram and hypersensitive troponin results, she was diagnosed with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Although the patient had no related medical history, she presented several risk factors, such as age greater than 30 years, assisted reproduction, and hyperlipidemia. After diagnosis, the patient received antiplatelet and anticoagulant treatment. Cesarean section and coronary angiography performed 7 d later showed stenosis and thrombus shadow of the right coronary artery. After receiving medication, the patient was in good condition.

This case suggests that, with the widespread use of assisted reproductive technology, more attention should be paid to perinatal healthcare, especially when chest pain occurs, to facilitate early diagnosis and intervention of AMI, and the etiology of AMI in pregnancy needs to be differentiated, especially between coronary spasm and spontaneous coronary artery dissection.

Core Tip: Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) during pregnancy is rare, especially in twin pregnancy. Pregnancy and assisted reproduction can increase the risk of AMI. AMI develops secondary to different etiologies, such as spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Herein, we present a case of AMI in a 33-year-old woman with twin pregnancy in the 31st week of gestation. She presented several risk factors, such as advanced age, assisted reproduction, and hyperlipidemia. The case suggests that more attention should be paid to perinatal healthcare, especially when chest pain occurs, and the etiology of AMI in pregnancy needs to be differentiated.

- Citation: Dai NN, Zhou R, Zhuo YL, Sun L, Xiao MY, Wu SJ, Yu HX, Li QY. Acute myocardial infarction in twin pregnancy after assisted reproduction: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(17): 4294-4302

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i17/4294.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i17.4294

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is a type of myocardial ischemic necrosis caused by acute occlusion of a coronary artery. AMI in pregnancy is a relatively rare occurrence that affects approximately 6.6 per 100000 women[1], and it is even rarer in twin pregnancy. Gestational AMI can occur at all stages of pregnancy[2], and it is more common in the third trimester. AMI in pregnancy can endanger the lives of the pregnant woman and the fetus. The disease develops secondary to different etiologies, such as spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD), atherosclerosis, coronary spasm, and thrombosis. Pregnancy itself is an independent risk factor for AMI. Moreover, obstetric factors such as advanced maternal age, multiparity, preeclampsia, and postpartum infection can increase the risk of AMI during pregnancy. Assisted reproduction may also increase the risk. Herein, we present a rare case of acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in twin pregnancy after assisted reproduc

A 33-year-old primigravid woman with a twin pregnancy in the 31st week of gestation, who had conceived after in vitro fertilization (IVF), presented to the hospital with intermittent chest tightness for 12 wk, aggravation for 1 wk, and chest pain for 4 h.

Twelve weeks ago, the patient had begun to experience chest tightness after a full meal, which had lasted for approximately 30 min each time. One week prior, her chest tightness was aggravated but was not accompanied by any other discomfort; hence, the patient did not visit a clinician. However, 4 h before admission, the patient had suddenly experienced poststernal colic after having her meal, which was not relieved, accompanied by sweating and awareness of defecation. The patient reported having a fall without injuries. She also complained of nausea and non-jet vomiting. The vomiting included stomach contents, and she had no syncope or loss of consciousness.

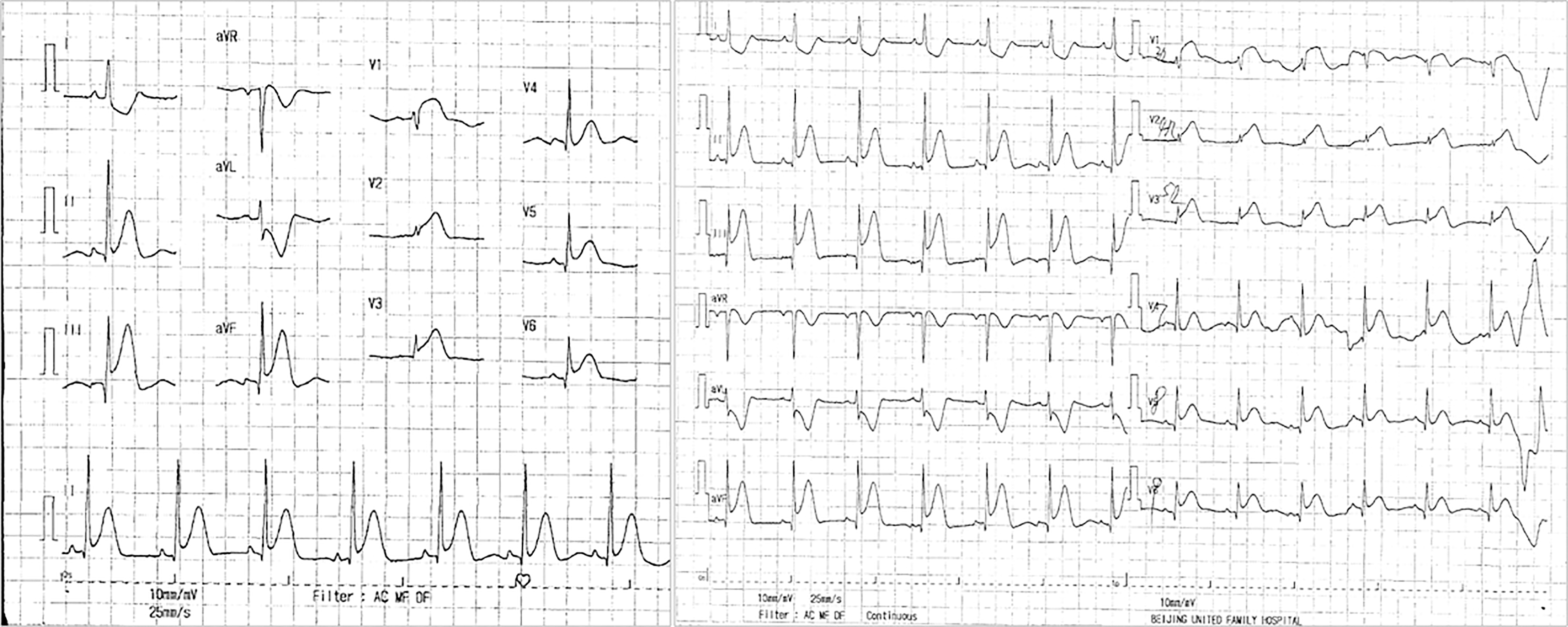

Subsequently, the patient was admitted to Beijing United Family Hospital and underwent certain examinations. Electrocardiogram (ECG) showed ST-segment elevation in leads II, III, aVF, V3R-V5R, and V7-V9 (Figure 1). The hypersensitive troponin level (TNI, 0.0074 μg/L) was increased, and the white blood cell (WBC, 16.5 × 109/L) count and D-dimer levels were elevated. Echocardiogram suggested akinesis of the inferior wall of the left ventricle and hypokinesis of the basic segment of the posterior wall. Despite the administration of ondansetron and saline, the patient’s chest pain failed to be relieved, after which she was intravenously administered with morphine. The patient was subsequently transferred to Beijing Anzhen Hospital.

The patient had no history of cardiovascular disease, conventional cardiovascular risk factors (such as hypertension, diabetes, and smoking), or relevant family history. Nonetheless, the patient was advised to rest in bed in the 24th week of gestation. She was also administered with nifedipine, dexamethasone, and progestin during the pregnancy and was subcutaneously administered with enoxaparin for her hypercoagulable state 1 wk prior to admission. In addition, the patient had been diagnosed with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo 2 wk prior to admission and was treated with Merislon. She was allergic to penicillin and egg yolk.

The patient had no relevant family history.

The patient was conscious on admission; her body temperature was 36.0 °C, pulse was 95 bpm, blood pressure was 119/73 mmHg, and respiratory rate was 20 breaths per minute. On physical examination, the patient appeared acutely ill, was in the left lying position, exhibited no special cardiopulmonary signs, and had a pregnant abdomen and irregular abdominal contractions.

Laboratory examination showed obviously elevated levels of the following: Creatine kinase 2924 U/L, lactate dehydrogenase 558 U/L, creatine kinase isoenzyme MB 21.5 ng/mL, TNI 47.72 ng/mL, and myoglobin 1442.7 ng/mL.

ECG showed that the ST segment in leads II, III, and aVF had dropped back to baseline levels, and the V3R-V5R leads were of the QS type.

Laboratory tests on admission showed increased levels of triglycerides, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP); the level of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol was normal. Measurement of thrombolytic activity showed decreased protein S activity and elevated plasminogen levels. The rapid CRP test revealed an elevated CRP level; in addition, the patient had an increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and her total protein and albumin levels were decreased. Serum antibody tests showed normal immunoglobulin (Ig) A, decreased IgG and IgM, and negative results for rheumatoid factor. The antinuclear antibody spectrum showed a weakly positive result for antihistone antibodies and negative results for other antibodies. Tests for antineutrophil plasma antibodies showed negative results. Tumor markers alpha-fetoprotein and β-human chorionic gonadotropin were also elevated. Routine urine tests showed strongly positive results for urine glucose and urine ketone bodies and an elevated urine WBC count, with a small amount of bacteria and a medium amount of mucus filaments. The 24-h total urinary protein was 464.07 mg/24 h. Other laboratory tests, such as thyroid function and glycosylated hemoglobin, showed normal results. Ultrasound examination of both lower limbs showed no obvious obstruction of deep and shallow veins or obvious stenosis of the double femoral artery. B-mode ultrasound showed two live fetuses.

The patient was diagnosed with coronary heart disease and acute inferior and posterior and right ventricular myocardial infarction. Her cardiac function was categorized as Killip class I.

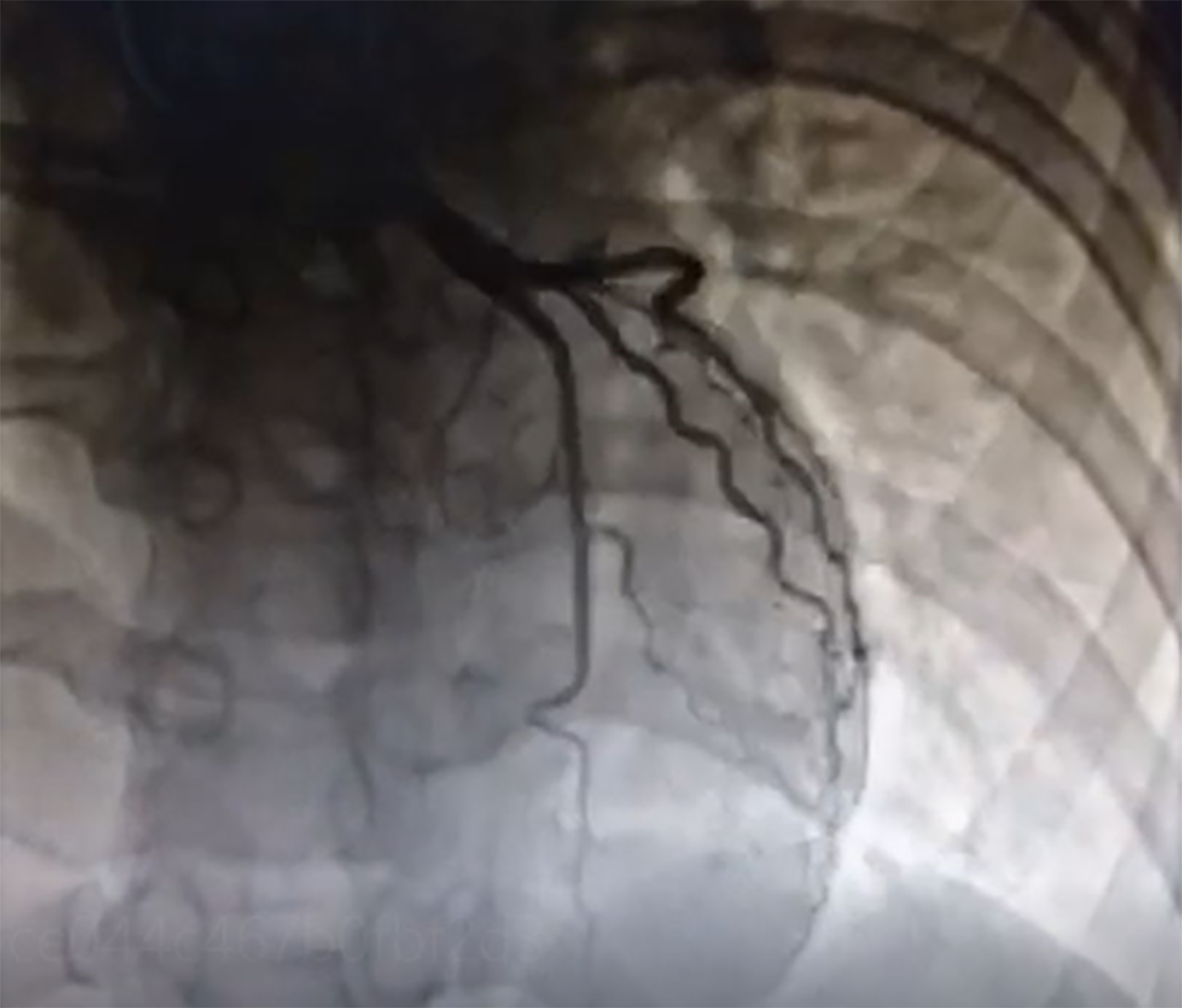

At the time of admission, owing to the possibility of preterm labor, the patient was administered with magnesium sulfate to inhibit contractions. Owing to the specific condition of the patient and the fact that the ST segment in leads II, III, and aVF of her ECG had dropped back to baseline levels, coronary intervention treatment was not performed immediately; antiplatelet aspirin 100 mg qd, anticoagulant enoxaparin 60 mg q12h, and antianginal isosorbide nitrate were considered. While continuously monitoring the patient’s condition during hospitalization, the patient’s vital signs were stable and she did not present chest pain, then a cesarean section was performed on the 7th day after admission, and two live babies were delivered. Simultaneous coronary angiography demonstrated severe narrowing of the right coronary and thrombus shadow, with a thrombolysis in myocardial infarction flow grade 3 (Figure 2); no obvious abnormality was observed on left coronary angiography (Figure 3). Owing to the extensive hemorrhage during cesarean section and placental implantation (adhesion type), continuation of coronary intervention treatment would require the use of heparin as an anticoagulant, which could increase the risk of hemorrhage; hence, simultaneous coronary intervention was not recommended. The patient was admitted to Beijing United Family Hospital and continued to receive aspirin and clopidogrel in combination, heparin anticoagulation, and statin lipid-regulating therapy for 1 mo.

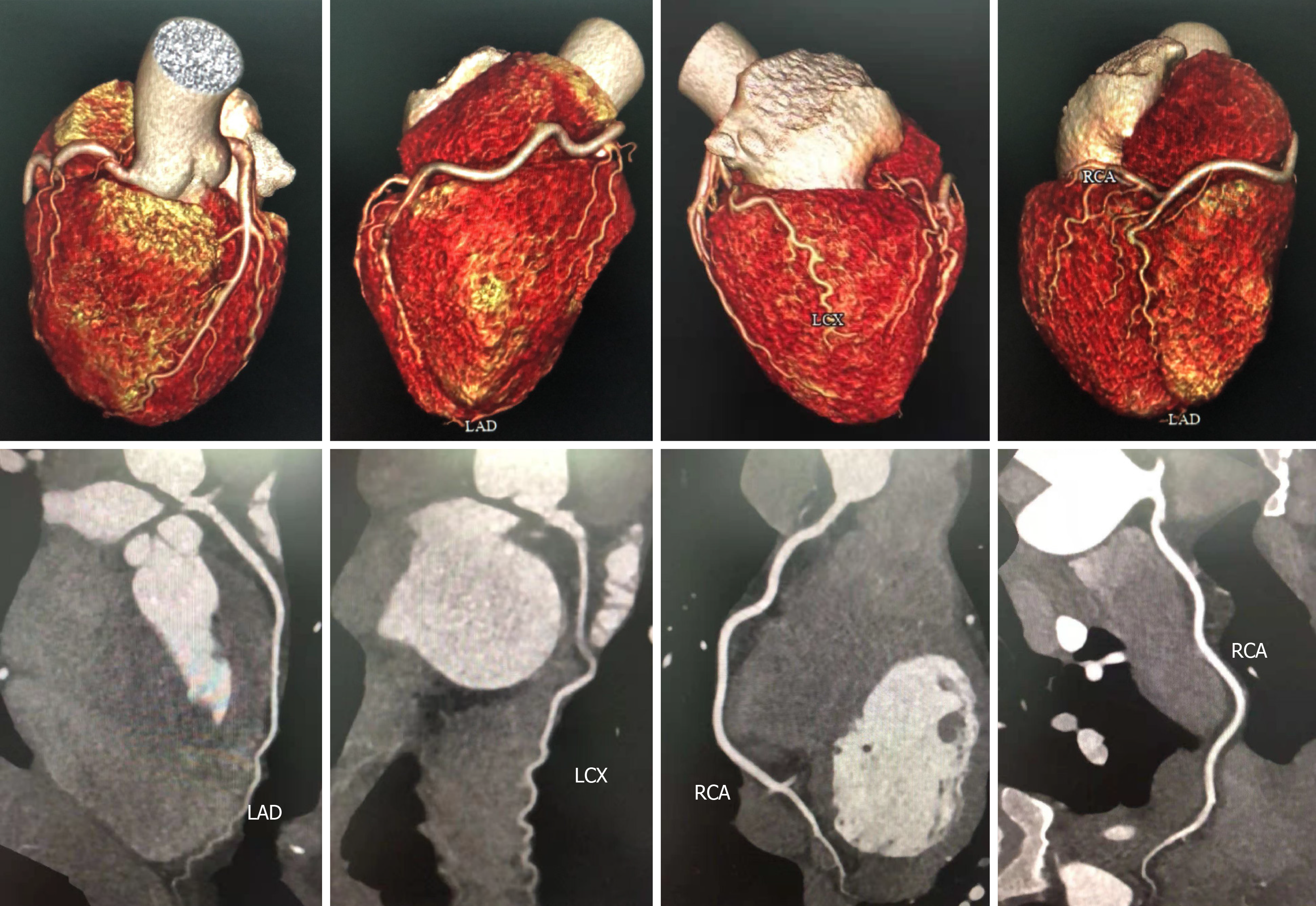

The patient continued to perform cardiac rehabilitation exercises and was in good condition without chest pain; her ECG, echocardiogram, and cardiac markers returned to normal. Moreover, her coronary computed tomography angioplasty (CTA) suggested that there was no obvious abnormality on her right coronary artery (Figure 4).

Gestational AMI is rare, but it is a well-described complication. The criteria for the diagnosis of AMI in pregnant women are the same as those in nonpregnant patients and consist primarily of symptoms, electrocardiographic changes, and cardiac markers[3]. Based on the patient’s symptoms and examinations results, she was definitively diagnosed with AMI.

It is interesting to note that the patient had no relevant history of cardiovascular disease or conventional cardiovascular risk factors, and coronary angiography showed severe stenosis and thrombus shadow of the right coronary artery. In addition to conventional cardiovascular risk factors (e.g., smoking, hypertension, and diabetes), pregnancy itself is an important risk factor of AMI. The risk factors for AMI in pregnancy also include advanced maternal age (> 30 years), multiparity, preeclampsia, postpartum infection, threatened preterm labor, thrombophilia, blood product transfusion, and other obstetric factors[4,5]. These factors are important in the development of AMI in pregnancy and can be observed in some cases (Table 1).

| Ref. | Type | Core tip |

| Guven et al[6], 2004 | Case report | A 38-yr-old gravida 8 para 5 woman at 26 wk of gestation presenting with myocardial infarction had experienced two myocardial infarction attacks previously, along with a history of hypertension for 5 yr. Hypertension was the risk factor and pregnancy in a woman with pre-existing ischaemic heart disease must be considered a high-risk situation. |

| Iadanza et al[7], 2007 | Case report | A 40-yr-old woman at her 38th wk of the gestational period was diagnosed with acute myocardial infarction with anterior ST elevation due to left coronary spasm. She was free from cardiovascular disease risk factors. |

| Fayomi and Nazar[8], 2007 | Case report | A 33-yr-old gravida 7 para 6 woman at 32 wk of gestation was diagnosed with anteroapical myocardial infarction, more likely due to atherosclerosis. She had a 15 cigarettes per day smoking habit. |

| Chen et al[9], 2009 | Case report | A 27-yr-old gravida 1 woman at 34 wk of gestation presented with acute myocardial infarction. Although having unremarkable medical history and no risk factors for cardiac disease, she was under the impression of antepartum hemorrhage, preterm labor, the use of ritodrine, and pregnancy-related elevations in cholesterol and triglyceride. |

| Baskurt et al[10], 2010 | Case report | A 24-yr-old woman in her 18th wk of pregnancy was diagnosed with myocardial infarction. She had two abortions during the last years and had received hydroxyprogesterone caproate treatment. Also, she presented with high lipid levels. |

| von Steinburg et al[11], 2011 | Case report | A 46-yr-old woman was diagnosed as having acute myocardial infarction in the 20th wk of twin pregnancy after in vitro fertilization. She had several cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension, obesity, hypercholesterolemia, smoking, and family history. And she presented preeclampsia. |

| Akçay et al[12], 2018 | Case report | A 34-yr-old female patient in her 36th wk of pregnancy presented with acute anterior myocardial infarction. She had no known risk factor for coronary artery disease, no history of substance abuse, and no any problems related to the pregnancy. But it was noted that this was her second pregnancy. |

| Diakite et al[13], 2019 | Case report | A 34-yr-old woman in her 35th wk of pregnancy was diagnosed with myocardial infarction. Her past medical history revealed no previous hospitalizations and no cardiovascular risk factors. But her laboratory tests revealed transient protein S deficiency. Deficits in protein S could result in thrombosis. |

Additionally, assisted reproduction may increase the risk of AMI in pregnancy. In recent years, with the extensive application of assisted reproductive technology (ART), mainly IVF and embryo transfer (IVF-ET), there have been many published reports of thromboembolism[14], including venous thromboembolism (VTE) and arterial thrombotic (AT) events. The incidence of AT was low as compared to that of VTEs. Most scholars think that it is related to superovulation during IVF-ET. Superovulation is prothrombotic and can be complicated by ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS). OHSS is characterized by third space fluid accumulation and hemoconcentration, which are considered the main cause of activation of the coagulation cascade[15], and can easily lead to thrombosis. But different studies had different results: A Danish national cohort study suggested that there was no evidence that assisted reproduction increases the risk of thrombosis[16]; a Southern India case series reported that among 12 cases of AMI during pregnancy, eight patients had undergone IVF[17]. Therefore, the risk of AMI during pregnancy related to ART has not been determined yet. And assisted reproduction more often leads to multiple-gestation pregnancies, which could increase cardiac load and myocardial oxygen consumption.

Based on the clinical characteristics of this patient, the causes of AMI can be analyzed from the following aspects: (1) Advanced age; (2) Assisted reproduction: This patient had conceived after IVF, which can be complicated by OHSS, with fluid shifts and an even greater risk of thrombosis; (3) Twin pregnancy: Twin pregnancy may increases cardiac load and myocardial oxygen consumption, and induce AMI; (4) Hyperlipidemia: The blood lipid levels of the patient were elevated, leading to increased blood formation and blood viscosity, which facilitated the development of embolism; (5) Hypercoagulable state of blood during pregnancy: Factors II, V, VII, VIII, IX, and X all increased during pregnancy, and the hypercoagulable and high-viscosity state of the blood during pregnancy was the main pathophysiological basis of thrombosis in this case; and (6) Hemodynamic changes: The patient had been bedridden for a long time during pregnancy and had a history of using tocolytic drugs; her blood flow was slow and stagnant, which created conditions for thrombus formation.

In terms of etiology, SCAD is often considered the main cause of AMI in pregnancy[4,18]. SCAD is an acute coronary event that is related to the development of a hematoma within the tunica media, and it can cause MI, which is most common in middle-aged women with few traditional cardiovascular risk factors[19]. The main precipitating factors for SCAD include pregnancy, excessive strenuous exercise, and emotional stress[19]. Its occurrence during pregnancy is related to changes in hormone levels and hemodynamics. And multiparity, advanced maternal age, and infertility therapies are considered as high risk factors for pregnancy-related SCAD[20]. Additionally, coronary spasm is also considered as another important cause, and it is associated with coronary endothelial dysfunction and increased responsiveness to vasoactive drugs. Continuous coronary spasm can cause continuous myocardial ischemia. AMI in pregnancy caused by coronary atherosclerosis has also been reported[8,21].

Considering that the patient was a young woman[22] and had no relevant family history of coronary heart disease, the possibility of coronary atherosclerotic plaque formation was small. And the coronary CTA during follow-up showed no significant abnormality on her right coronary. Therefore, the most likely etiology of AMI in this patient was coronary spasm or SCAD, which needs to be differentiated. The differential diagnosis of coronary spasm and SCAD depends on the response to intracoronary vasodilator injection and intracoronary images [such as intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) or optical coherence tomography (OCT)][19]. Unfortunately, IVUS and OCT were not performed at that time. However, SCAD was more likely to be the etiology of the patient’s AMI: The absence of chest pain during coronary angiography and the presence of right coronary stenosis and thrombus shadow on her coronary angiography were more suggestive of SCAD. Furthermore, her absence of chest pain episodes and follow-up CTA were more suggestive of SCAD.

The management of AMI in pregnancy is similar to that in the general population, including revascularization techniques[23], which include thrombolytic therapy and therapeutic percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). PCI has shown good safety in terms of maternal and fetal survival, and the 2018 ESC Guidelines state that the effects of ionizing radiation should not preclude primary PCI in pregnant patients with standard indications for revascularization in AMI[23]. However, considering the peculiarity of the condition of this patient and the fact that the ST segment in her ECG had dropped back to baseline levels, we did not perform PCI immediately. During follow-up, she did not undergo coronary intervention because the etiology of her AMI was considered to be SCAD. Most of the hematomas of SCAD can be absorbed within 30 d after conservative treatment, and the blood vessels will repair themselves[19]. Moreover, the therapeutic effect of PCI for SCAD patients is uncertain. Therefore, the patient was treated conservatively.

In medication, the safety of standard medical treatment in infarction remains uncertain for pregnant patients. Low-dose aspirin seems safe, as are nitrates, heparin, nifedipine, and certain beta blockers (e.g., metoprolol and atenolol). There are no case reports linked to the use of aspirin at a low dose of 80-150 mg per day, and in most opinions the potential benefits of aspirin usage far outweigh the risks[24]. Clopidogrel is also recommended and is still the most widely used thienopyridine, although case reports have demonstrated an association between the use of clopidogrel and maternal thrombocytopenia, maternal hemorrhage, and fetal demise[24]. However, we should note that statins are contraindicated during pregnancy, so this patient was given statins after delivery.

Owing to the extensive application of ART, the specific conditions in pregnancy, and the danger of AMI, more attention should be paid to perinatal healthcare of pregnant women, especially those who experience chest pain, to ensure early diagnosis and intervention of AMI. In addition, the etiology of AMI in pregnancy needs to be differentiated, especially between coronary spasm and SCAD. The safety of the medication for the pregnant woman and the fetus needs to be considered.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Satoh H S-Editor: Liu M L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Kennedy BB, Baird SM. Acute Myocardial Infarction in Pregnancy: An Update. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2016;30:13-24; quiz E1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Roth A, Elkayam U. Acute myocardial infarction associated with pregnancy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:171-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 260] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Elkayam U, ed. Cardiac Problems in Pregnancy.4th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2019: 201-219. |

| 4. | Elkayam U, Jalnapurkar S, Barakkat MN, Khatri N, Kealey AJ, Mehra A, Roth A. Pregnancy-associated acute myocardial infarction: a review of contemporary experience in 150 cases between 2006 and 2011. Circulation. 2014;129:1695-1702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 289] [Article Influence: 26.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | James AH, Jamison MG, Biswas MS, Brancazio LR, Swamy GK, Myers ER. Acute myocardial infarction in pregnancy: a United States population-based study. Circulation. 2006;113:1564-1571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 353] [Cited by in RCA: 337] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Guven S, Guvendag Guven ES, Durukan T, Kes S. Successful twin pregnancy after myocardial infarction. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;44:168-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Iadanza A, Del Pasqua A, Barbati R, Carrera A, Gentilini R, Favilli R, Pierli C. Acute ST elevation myocardial infarction in pregnancy due to coronary vasospasm: a case report and review of literature. Int J Cardiol. 2007;115:81-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Fayomi O, Nazar R. Acute myocardial infarction in pregnancy: a case report and subject review. Emerg Med J. 2007;24:800-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chen YC, Chang YM, Yeh GP, Tsai HD, Hsieh CT. Acute myocardial infarction during pregnancy. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;48:181-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Başkurt M, Ozkan T, Arat Ozkan A, Gürmen T. Acute myocardial infarction in a young pregnant woman. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg. 2010;10:285-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | von Steinburg SP, Klein E, Langwieser N, Kastrati A, Schneider KT, Zohlnhöfer D. Coronary stenting after myocardial infarction during twin pregnancy--a case report. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2011;30:485-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Akçay M, Meriç M, Gedikli Ö, Yüksel S, Şahin M. Acute anterior myocardial infarction in the 36th week of pregnancy: A successful stepwise treatment approach. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2018;46:702-705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Diakite S, Radi FZ, Zarzur J, Cherti M. Myocardial infarction in a pregnant woman revealing a transitional deficit in protein S: a rare case report. Pan Afr Med J. 2019;34:27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Henriksson P. Cardiovascular problems associated with IVF therapy. J Intern Med. 2021;289:2-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Delvigne A, Rozenberg S. Review of clinical course and treatment of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS). Hum Reprod Update. 2003;9:77-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hansen AT, Kesmodel US, Juul S, Hvas AM. No evidence that assisted reproduction increases the risk of thrombosis: a Danish national cohort study. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:1499-1503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Smilowitz NR, Reynolds HR. In Reply-Acute Myocardial Infarction During Pregnancy and the Puerperium: Experiences and Challenges From Southern India. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94:919-920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hayes SN, Kim ESH, Saw J, Adlam D, Arslanian-Engoren C, Economy KE, Ganesh SK, Gulati R, Lindsay ME, Mieres JH, Naderi S, Shah S, Thaler DE, Tweet MS, Wood MJ; American Heart Association Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Genomic and Precision Medicine; and Stroke Council. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection: Current State of the Science: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137:e523-e557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 647] [Cited by in RCA: 819] [Article Influence: 117.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hayes SN, Tweet MS, Adlam D, Kim ESH, Gulati R, Price JE, Rose CH. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:961-984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 294] [Article Influence: 73.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Tweet MS, Hayes SN, Codsi E, Gulati R, Rose CH, Best PJM. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection Associated With Pregnancy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:426-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 29.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Jaiswal A, Rashid M, Balek M, Park C. Acute myocardial infarction during pregnancy: a clinical checkmate. Indian Heart J. 2013;65:464-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gulati R, Behfar A, Narula J, Kanwar A, Lerman A, Cooper L, Singh M. Acute Myocardial Infarction in Young Individuals. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95:136-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 35.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Regitz-Zagrosek V, Roos-Hesselink JW, Bauersachs J, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Cífková R, De Bonis M, Iung B, Johnson MR, Kintscher U, Kranke P, Lang IM, Morais J, Pieper PG, Presbitero P, Price S, Rosano GMC, Seeland U, Simoncini T, Swan L, Warnes CA; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2018 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3165-3241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 811] [Cited by in RCA: 1325] [Article Influence: 189.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Edupuganti MM, Ganga V. Acute myocardial infarction in pregnancy: Current diagnosis and management approaches. Indian Heart J. 2019;71:367-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |