Published online Jun 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i16.4040

Peer-review started: January 15, 2021

First decision: January 24, 2021

Revised: January 29, 2021

Accepted: March 23, 2021

Article in press: March 23, 2021

Published online: June 6, 2021

Processing time: 118 Days and 12.6 Hours

Atherosclerosis represents the main cause of myocardial infarction (MI); other causes such as coronary embolism, vasospasm, coronary-dissection or drug use are much rarely encountered, but should be considered in less common clinical scenarios. In young individuals without cardiovascular risk factors, the identification of the cause of MI can sometimes be found in the medical history and previous treatments undertaken.

We present the case of a 34-year-old man presenting acute inferior ST-elevation MI without classic cardiac risk factors. Seven years ago, he suffered from orchidopexy for bilateral cryptorchidism, and was recently diagnosed with right testicular seminoma for which he had to undergo surgical resection and chemotherapy with bleomycin, etoposide and cisplatin. Shortly after the first chemotherapy treatment, namely on day five, he suffered an acute MI. Angiography revealed a mild stenotic lesion at the level of the right coronary artery with suprajacent thrombus and vasospasm, with no other significant lesions on the other coronary arteries. A conservative treatment was decided upon by the cardiac team, including dual antiplatelets therapy and anticoagulants with good further evolution. The patient continued the chemotherapy treatment according to the initial plan without other cardiovascular events.

In young individuals with no cardiovascular risk factors undergoing aggressive chemotherapy, an acute MI can be caused by vascular toxicity of several anti-cancer drugs.

Core Tip: Atherosclerosis represents the main cause of acute myocardial infarction (MI), but less frequent causes should be evaluated in young individuals not at risk of such cardiac events. Aggressive chemotherapy for testicular seminoma increases vascular toxicity that may induce acute MI, complicating the clinical course of the subject. Under conservative treatment with antiplatelets and anticoagulants, the clinical evolution of subjects is favorable, but with the extant risk of repeating cardiac events on further chemotherapy courses.

- Citation: Scafa-Udriste A, Popa-Fotea NM, Bataila V, Calmac L, Dorobantu M. Acute inferior myocardial infarction in a young man with testicular seminoma: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(16): 4040-4045

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i16/4040.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i16.4040

Testicular cancer is a prototypic type of tumor in young men, being at the same time the most frequent solid tumor in the age range of 15 to 40[1]. Despite the negative clinical features and psychological impact[2], the curability rate of testicular cancer with modern therapy is high, with a low mortality at 5- and 10-years[1]. Side effects among testicular cancer survivors are significant, and result from underlying neoplasia and treatment[3].

By all histological subtypes of testicular tumors, seminomas are most frequently encountered in patients with a history of cryptorchidism. In subjects presenting stage I or II seminoma, chemotherapy with cisplatin-based cures assures roughly a 90% rate of curability[4]. Although efficient, the combination of bleomycin, etoposide and cisplatin (BEP) is associated with many side effects that include nephrotoxicity, neuropathy, infertility, vascular toxicity or secondary leukemia[5].

Vascular toxicity can take various forms including the Raynaud phenomenon, myocardial infarction (MI) or cerebrovascular events. Even if a study showed no supplementary risk of acute vascular events in patients receiving cisplatin-based chemotherapy for testicular cancer[6], we present the case of a 34-year-old man who developed inferior MI during the first course of chemotherapy for testicular seminoma. The patient gave informed consent for the presentation of the clinical case.

A 34-year-old man was admitted to the cardiology department for intense chest pain, malaise and diaphoresis. This is the first chest pain episode, the patient describing it as constrictive and not responding to anti-inflammatory medication taken at home.

The chest pain developed 2 h previously, approximately 12 h after he ended his first course of chemotherapy for right testicular seminoma.

Seven years prior, the patient suffered from orchidopexy for bilateral cryptorchidism and had been diagnosed with right testicular seminoma two months prior to the incident under review; surgical resection was performed shortly after the diagnosis and was followed by chemotherapy. The latter was a combination of three anticancer drugs (BEP): Bleomycin 30 mg on days 1-5, 8 and 15, and etoposide 100 mg/mp and cisplatin 20 mg/mp in the first five days. The chemotherapy course would have been repeated on day 21.

On day 5, shortly after the first chemotherapy session, the patient developed severe acute chest pain, 10 out of 10 on the visual analogue scale.

He had neither cardiovascular risk factors, nor a family history of cardiovascular events.

The clinical examination on admission pinpointed, blood pressure of 120/80 mmHg, a heart rate of 85 beats/min, with cardiac and pulmonary examination showing no significant pathological findings.

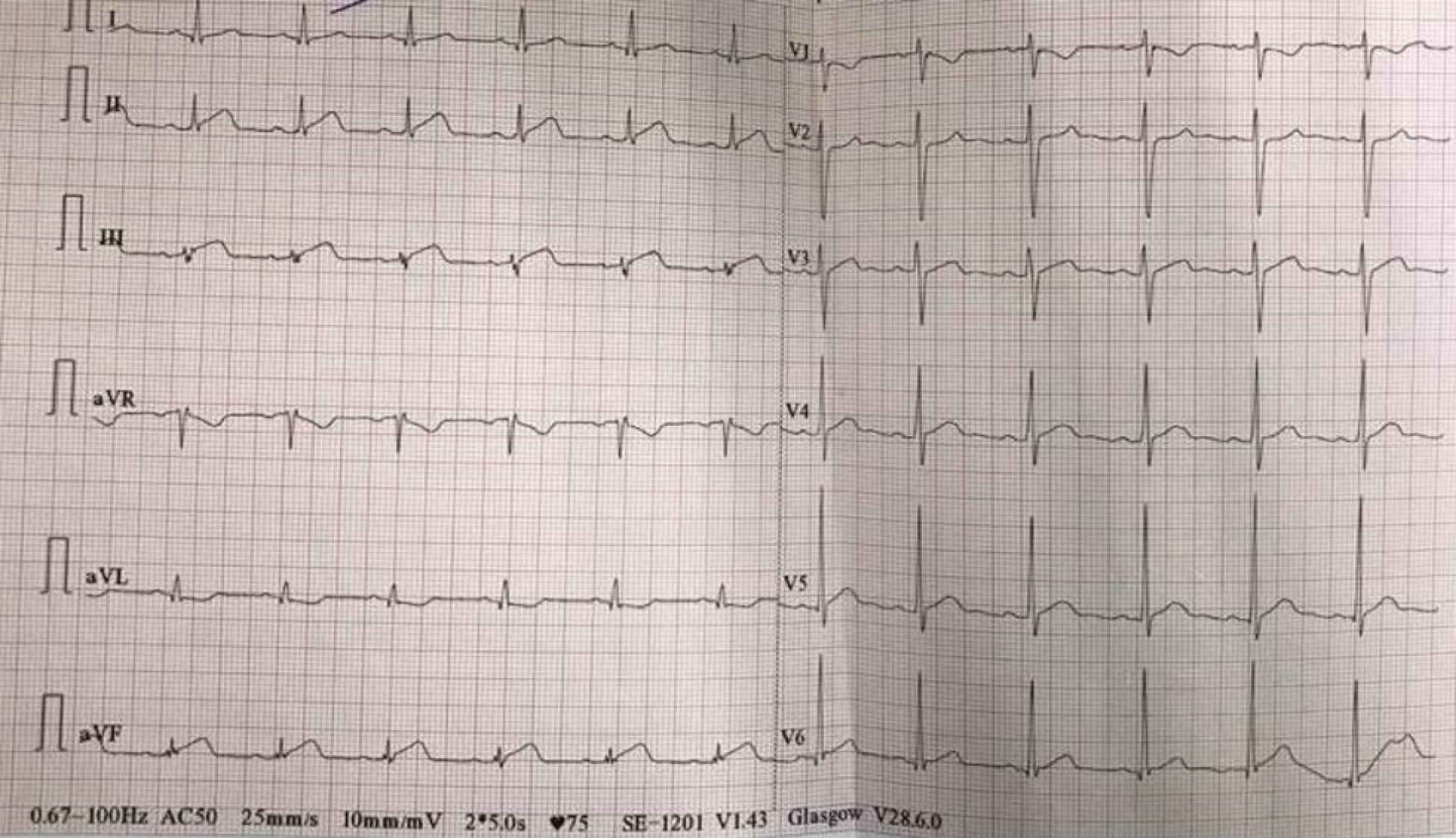

The electrocardiogram revealed sinus rhythm, ST-segment elevation in the inferior leads (Figure 1) and elevated markers of necrosis (troponin I 8.37 ng/mL, CK-MB 18.23 ng/mL). Total white blood cell count and neutrophil count were within normal ranges.

Total, low-density and high-density lipoproteins cholesterol, as well as glycated haemoglobin were within the normal cut-off values.

The subject’s echocardiography showed hypokinesia in the basal segments of the inferior and infero-lateral walls of the left ventricle, with a global ejection fraction 55%. Furthermore, no significant valvular abnormalities were detected.

The patient was given loading dosages of aspirin and clopidogrel and was directly taken to the catheter laboratory for an angiography, with the final diagnosis of acute inferior ST-elevation MI.

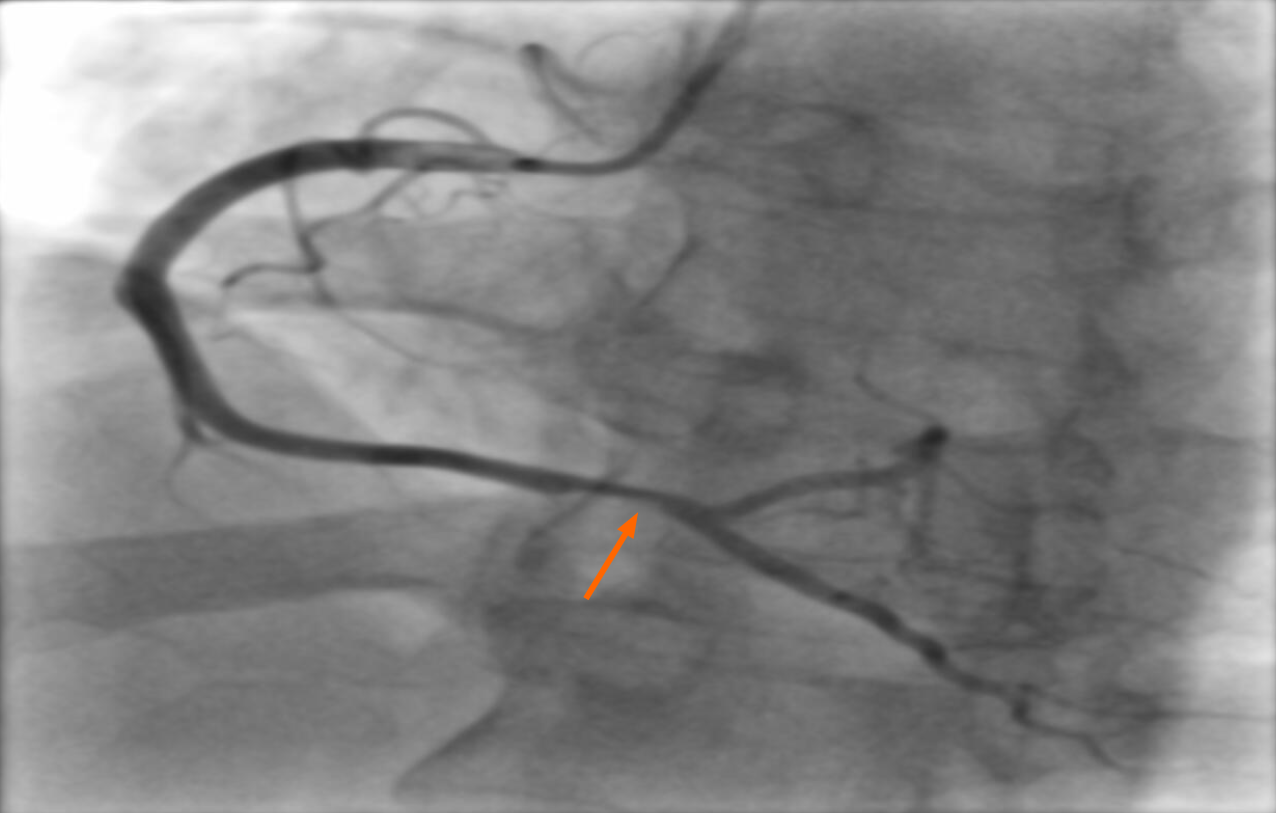

The left main, anterior interventricular and circumflex artery were normal, while the right coronary artery showed a mild stenotic lesion (30%-40%) with slightly suprajacent thrombus and vasospasm (Figure 2).

Medical treatment and follow-up were decided in the catheter laboratory. The patient was admitted to the coronary care unit for 3 d, where he was treated with aspirin, clopidogrel, a calcium blocker (namely verapamil), atorvastatin, isosorbide dinitrate, un-fractioned heparin and perindopril. He remained asymptomatic and was discharged with the same treatment except anticoagulants, in order to continue the chemotherapy according to the initial protocol.

The patient proceeded with chemotherapy without other acute cardiovascular events. At six months later he was asymptomatic from a cardiovascular point of view, with no evidence of active disease found during an abdominopelvic computer tomography. He remained under long-term surveillance for both distant and nodal relapse.

In a patient without cardiovascular risk factors, the emergence of an acute MI shortly after the first course of BEP makes chemotherapy a very likely cause of the acute ischemic event, although the exact pathophysiological mechanisms are difficult to prove conclusively. The patient was in sinus rhythm, and echocardiography ruled out intra-cardiac sources of thrombo-embolism such as intra-cardiac thrombus or tumor, mitral stenosis or other risk factors for embolism, excluding a thromboembolism-related MI. Furthermore, emboli frequently stop at the level of stenosis, bifurcation or tortuosity, this not being the case of the thrombus identified in our patient that, with a high probability, was formed in situ; moreover, an atherosclerotic cause of this acute MI is less likely, as the other coronary segments showed no signs of atherosclerosis. Although rare and unpredictable, Takotsubo syndrome is associated with several chemotherapy regimens (mainly with 5-fluorouracil), reason for which we had considered this diagnosis. However, the patient did not meet the Mayo clinic criteria[7], since he did not have dyskinesia of left mid-ventricular segment with or without apical involvement as the Mayo clinic criteria requires for such a diagnosis (Video 1, Video 2, and Video 3). Furthermore, the chemotherapy undertaken by our patient is not associated with Takotsubo syndrome, but given the unpredictability of the disease this possibility should be considered even if not reported previously. Consequently, we speculate the patient suffered an endothelial lesion with in situ thrombus formation promoted by the anticancer drugs with suprajacent coronary vasospam, but in the absence of optical coherence tomography or intravascular echocardiography the exact mechanism cannot be established. For the evaluation of coronary vasospasm, the right coronary artery was injected with 200 μg nitroglycerine with the slight improvement of the acute myocardial infarction culprit lesion, but without its total disappearance. The most likely explanation for the reduced response to nitroglycerine is that the lesion encountered on angiography is the result of a complex mechanism that also includes endothelial erosion apart from coronary vasoconstriction. The erosion of the endothelial taken as one main mechanism of cisplatin vascular toxicity is supported by both experimental and clinical data regarding endothelial damage, apoptosis as well as platelet adherence, activation and aggregation[8,9]. Moreover, an increasing body of evidence points to the fact that cisplatin also induces endothelial dysfunction, affecting both the relaxation and contractile function through severe damage to blood vessel walls[10]. The mechanisms underlying the latter are mainly the reduction of endothelial nitric oxide synthetase and an increase in plasminogen activator inhibitor 1[11], but also include other mechanisms such as hydrogen sulphide availability[12]. Thrombus formation is the result of one or more of the following factors that build Virchow’s triad: endothelial dysfunction, hypercoagulation and blood stagnation. All anticancer drugs our patient took can induce either one or more of the factors within Virchow’s triad. Bleomycin increases interleukin-1 secretion at the pulmonary level, and further on the latter acts on the vascular endothelial promoting procoagulant activity and leukocyte adhesion[13]. Other studies have shown that cisplatin induces coronary spasms[14] and even direct damage to vascular endothelium[8]. Moreover, etoposide is associated with the increased risk of MI[15] especially if used in conjunction with other cardiotoxic agents. Another mechanism of thrombosis which could have explained the broader angiographic picture is a prolonged vasospasm with coronary occlusion and secondary thrombus formation[16].

For the case presented above we hypothesize that the particular chemotherapy regimen employed induced not only an endothelial dysfunction with vasospasm, but also a direct endothelial lesion that promoted thrombus formation in a subject predisposed to thrombosis given the neoplasia and anticancer treatment. Procoagulant activity increases mainly when multiple drugs work synergistically in combination, as in the case of our patient[6]. Furthermore, many factors contribute to the systemic overall cardiotoxicity, some related to the drugs themselves but also to the individual. Moreover, given that young individuals without any cardiovascular risk factors are predisposed to ischemic cardiovascular events, preventive measures during chemotherapy should actively be implemented; for example, one such measure could be the addition of anticoagulants or aspirin[17] to the adjuvant therapy, along with the reduction in dosages, the increase of time-intervals between treatment administration and the avoidance of certain combinations of anti-cancer drugs.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: European Society of Cardiology, No. 778669.

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Romania

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Horowitz JD S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Bevilacqua MP, Pober JS, Wheeler ME, Cotran RS, Gimbrone MA Jr. Interleukin-1 activation of vascular endothelium. Effects on procoagulant activity and leukocyte adhesion. Am J Pathol. 1985;121:394-403. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Dieckmann KP, Struss WJ, Budde U. Evidence for acute vascular toxicity of cisplatin-based chemotherapy in patients with germ cell tumour. Anticancer Res. 2011;31:4501-4505. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Dong W, Gang W, Liu M, Zhang H. Analysis of the prognosis of patients with testicular seminoma. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:1361-1366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Della Coletta Francescato H, Cunha FQ, Costa RS, Barbosa Júnior F, Boim MA, Arnoni CP, da Silva CG, Coimbra TM. Inhibition of hydrogen sulphide formation reduces cisplatin-induced renal damage. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:479-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fung C, Dinh P Jr, Ardeshir-Rouhani-Fard S, Schaffer K, Fossa SD, Travis LB. Toxicities Associated with Cisplatin-Based Chemotherapy and Radiotherapy in Long-Term Testicular Cancer Survivors. Adv Urol. 2018;2018:8671832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gil T, Sideris S, Aoun F, van Velthoven R, Sirtaine N, Paesmans M, Ameye L, Awada A, Devriendt D, Peltier A. Testicular germ cell tumor: Short and long-term side effects of treatment among survivors. Mol Clin Oncol. 2016;5:258-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Herradón E, González C, Uranga JA, Abalo R, Martín MI, López-Miranda V. Characterization of Cardiovascular Alterations Induced by Different Chronic Cisplatin Treatments. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Huddart RA, Norman A, Shahidi M, Horwich A, Coward D, Nicholls J, Dearnaley DP. Cardiovascular disease as a long-term complication of treatment for testicular cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1513-1523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 415] [Cited by in RCA: 381] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ito D, Shiraishi J, Nakamura T, Maruyama N, Iwamura Y, Hashimoto S, Kimura M, Matsui A, Yokoi H, Arihara M, Irie H, Hyogo M, Shima T, Kohno Y, Matsumuro A, Sawada T, Matsubara H. Primary percutaneous coronary intervention and intravascular ultrasound imaging for coronary thrombosis after cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Heart Vessels. 2012;27:634-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jiang Y, Shan S, Gan T, Zhang X, Lu X, Hu H, Wu Y, Sheng J, Yang J. Effects of cisplatin on the contractile function of thoracic aorta of Sprague-Dawley rats. Biomed Rep. 2014;2:893-897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Joharatnam-Hogan N, Cafferty F, Hubner R, Swinson D, Sothi S, Gupta K, Falk S, Patel K, Warner N, Kunene V, Rowley S, Khabra K, Underwood T, Jankowski J, Bridgewater J, Crossley A, Henson V, Berkman L, Gilbert D, Kynaston H, Ring A, Cameron D, Din F, Graham J, Iveson T, Adams R, Thomas A, Wilson R, Pramesh CS, Langley R; Add-Aspirin Trial Management Group. Aspirin as an adjuvant treatment for cancer: feasibility results from the Add-Aspirin randomised trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4:854-862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kobayashi Y, Ueda Y, Matsuo K, Nishio M, Hirata A, Asai M, Nemoto T, Murakami A, Kashiwase K, Kodama K. Vasospasm-induced acute myocardial infarction-Thrombus formation without thrombogenic lesion at the culprit. J Cardiol Cases. 2013;8:138-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Malec JF, Romsaas EP, Messing EM, Cummings KC, Trump DL. Psychological and mood disturbance associated with the diagnosis and treatment of testis cancer and other malignancies. J Clin Psychol. 1990;46:551-557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Nuver J, Smit AJ, van der Meer J, van den Berg MP, van der Graaf WT, Meinardi MT, Sleijfer DT, Hoekstra HJ, van Gessel AI, van Roon AM, Gietema JA. Acute chemotherapy-induced cardiovascular changes in patients with testicular cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9130-9137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Park JS, Kim J, Elghiaty A, Ham WS. Recent global trends in testicular cancer incidence and mortality. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e12390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 24.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Scantlebury DC, Prasad A. Diagnosis of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Circ J. 2014;78:2129-2139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Schecter JP, Jones SE, Jackson RA. Myocardial infarction in a 27-year-old woman: possible complication of treatemtn with VP-16-213 (NSC-141540), mediastinal irradiation, or both. Cancer Chemother Rep. 1975;59:887-888. [PubMed] |