Published online May 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i14.3472

Peer-review started: December 28, 2020

First decision: January 17, 2021

Revised: January 18, 2021

Accepted: March 15, 2021

Article in press: March 15, 2021

Published online: May 16, 2021

Processing time: 122 Days and 1.1 Hours

Autoimmune hepatitis can cause liver fibrosis, liver cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Its treatment option include the use of steroids and/or immune-suppressive agents such as azathioprine. However, these drugs have some side effects. Thus, close follow-up is needed during treatment. Here, we present an extremely rare case of a patient with an autoimmune hepatitis who died from necrotizing gastritis during immunosuppressive treatment.

A 52-year-old female patient was diagnosed with autoimmune hepatitis. We treated this patient with immunosuppressive agents. High-dose steroid treatment was initially started. Then azathioprine treatment was added while steroid was tapering. Five weeks after the start of treatment, she visited the emergency room due to generalized abdominal pain and vomiting. After computed tomography scan, the patient was diagnosed with necrotizing gastritis and the patient progressed to septic shock. Treatment for sepsis was continued in the intensive care unit. However, the patient died at 6 h after admission to the emergency room.

In patients with autoimmune infections undergoing immunosuppressant therapy, rare complications such as necrotizing gastritis may occur, thus requiring clinical attention.

Core Tip: Primary treatment for autoimmune hepatitis is using immunosuppressants such as steroids and azathioprine. When using immunosuppressants, various side effects may occur. Thus, close observation is necessary. This case report is the first one to describe the occurrence of necrotizing gastritis, a very rare complication of immunosuppressants, in a patient with autoimmune hepatitis.

- Citation: Moon SK, Yoo JJ, Kim SG, Kim YS. Extremely rare case of necrotizing gastritis in a patient with autoimmune hepatitis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(14): 3472-3477

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i14/3472.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i14.3472

Autoimmune hepatitis is a rare liver disorder presenting persistent inflammation of the liver parenchyma. It is characterized by interfacial hepatitis, elevated liver enzyme levels, hypergammaglobulinemia, and the appearance of autoimmune antibodies[1,2]. If autoimmune hepatitis is not well controlled, it can continuously cause liver fibrosis and progress to liver cirrhosis and/or hepatocellular carcinoma[3,4]. The 2019 American Association for the Study of the Liver practice guideline recommends prednisolone and azathioprine combination therapy as a first-line drug in patients without cirrhosis, acute severe autoimmune hepatitis, or acute liver failure[5-7]. In particular, prednisolone is recommended to be used at an amount of 1 mg or more per 1 kg of body weight at the beginning of treatment. Screening for its various side effects such as infection and bone marrow suppression are essential[5,6,8,9]. Azathioprine is used in maintenance treatment. It is also a type of immunosuppressant that can cause various side effects. Here, we report an extremely rare case of a patient who died due to a sudden onset of necrotizing gastritis as a side effect of an immunosuppressant.

A 52-year-old female visited the emergency room of our hospital (Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital) due to abdominal pain nausea and vomiting.

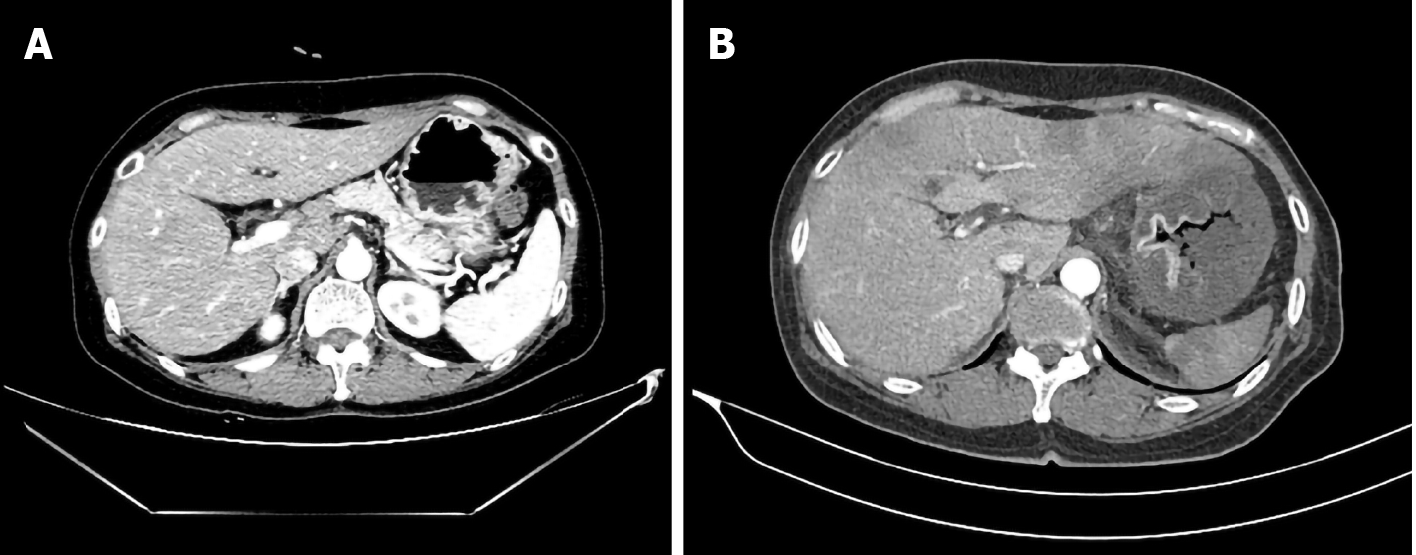

Five weeks before visiting the emergency room, she visited our outpatient clinic of gastroenterology department due to an increased level of liver enzyme alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (at 320 U/mL) that was accidentally found at a health screening test. Blood test showed positive autoimmune antibody (anti-nuclear antibody 1:1280 and anti-mitochondrial antibody positive). Her immunoglobulin G was elevated to 1577 mg/dL. Abdominal ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) showed coarse liver surface, indicating that she had chronic liver disease (Figure 1A). Therefore, a liver biopsy was performed and the patient was finally diagnosed with an overlap syndrome predominantly with features of an autoimmune hepatitis. After the biopsy, the patient started to take high dose of ursodeoxycholic acid (15 mg/kg) plus prednisolone 40 mg daily for two weeks. After two weeks from the initial treatment, the dose of ursodeoxycholic acid was maintained and prednisolone was reduced by 10 mg every week. Six days before the emergency room visit, prednisolone was reduced to 5 mg and azathioprine 50 mg was maintained.

From two days before visiting the emergency room, the patient had symptoms of mild heartburn and abdominal pain. One day before the emergency room visit, her abdominal pain worsened to the point that it interfered with her sleep. In addition, she had more symptoms of nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Thus, she finally visited the emergency room.

The patient had an unremarkable past medical history except for an overlap syndrome described above.

At the time of the emergency room visit, her blood pressure was normal with a systolic blood pressure of 130 mmHg and a diastolic blood pressure of 80 mmHg. She had a mild fever (37.6 °C) and tachycardia (heart rate of 110 beats/min). She also had tachypnea at 30 breaths per minute. She had abdominal tenderness in the epigastric to the left upper quadrant area. Her abdomen was a little hard. However, no rebound tenderness was observed.

During the outpatient treatment period, her counts of white blood cells, red blood cells, and platelets were all normal. However, at the time of the emergency room visit, her counts of white blood cells and platelets were reduced to 700/µL and 61000/µL, respectively. Since her neutrophil level was decreased to 5% and C-reactive protein level was elevated to 14.35 mg/dL, systemic infection was strongly suspected. Test results for liver enzymes were: aspartate aminotransferase, 347 U/L; ALT, 52 U/L; and gamma glutamyl transferase, 458 U/L. Her prothrombin time international normalized ratio was 1.2.

Contrast-enhanced abdominal CT revealed a huge stomach with layered wall thickening in the fundus and upper body (Figure 1B), which was not found before she received treatment (Figure 1A). Air in the stomach wall was observed in some areas. Decrease of mucosal enhancement was also detected.

We diagnosed the patient with necrotizing gastritis accompanying septic shock.

Her blood pressure was normal at the time of admission to the emergency room. However, at 30 min after the emergency room visit, her blood pressure decreased (systolic blood pressure was less than 80 mmHg). The patient was immediately transferred to the intensive care unit and intravenous hydration and antibiotic treatment were started immediately. At two hours after admission to the intensive care unit, her blood pressure was increased (systolic blood pressure at 127 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure at 95 mmHg) while receiving inotropics (norepinephrine) and fluid treatment.

Her heart rate suddenly started to slow from three hours after entering the intensive care unit. Bedside echocardiography was performed and severe stress-induced cardiomyopathy with ejection fraction of less than 10% was observed. Thus, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation was prepared. During preparation for the procedure, sudden cardiac arrest with pulseless electrical activity started. Accordingly, cardiopulmonary resuscitation was performed for more than 30 min. extracorporeal membrane oxygenation was also applied. However, the patient died of cardiac arrest.

Treatment for autoimmune hepatitis is determined based on the severity of symptoms, elevation of serum ALT and gamma globulin, histological findings, and various other side effects of treatment[10,11]. The recommended starting point of treatment varies slightly for each guideline. If levels of ALT and gamma globulin are normal or not deviating significantly from normal and if hepatitis is not severe on liver biopsy, treatment is not recommended because significant liver damage is not likely to progress in these cases.

However, if ALT level is elevated more than 5 times or gamma globulin levels are high as in our patient, immunosuppressive treatment is recommended. Since both steroids and azathioprine have side effects, regular liver function tests, blood sugar, and complete blood count test are crucial after treatment initiation[12-14]. In most cases, follow up laboratory test is recommended every week, especially for first month after treatment initiation. In our case, although physical examinations and blood tests were performed every week, we could not predict the occurrence of sudden necroti

For our case, immunosuppressants might have acted as risk factors for necrotizing gastritis. Of the two drugs (steroid and azathioprine) used for our case, azathioprine was more likely to be the cause. Common gastrointestinal side effects of azathioprine are known as nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and increased stomach irritation. In addition, both leukopenia and infection observed in this patient are side effects reported for azathioprine users[15]. Considering that steroids were taped for the patient, azathioprine was more likely to be the cause. According to Teich et al[16], azathioprine side effects are more common in patients taking oral steroids. Thus, steroid might act as a secondary exacerbation factor.

Since necrotizing gastritis is a disease with a very low incidence, we could not find any other case of necrotizing gastritis in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. Instead, we searched for reports of necrotizing gastritis in patients without autoimmune hepatitis (Table 1)[17-26]. In most cases, treatment included total gastrectomy or the use of antibiotics[27,28]. In our case, initial treatment was also the use of intravenous antibiotics. However, the patient deteriorated despite rapid antibiotic administration and fluid treatment. Thus, anaerobic bacteria were highly likely to be the cause of sepsis. This was hypothetical because no bacteria were identified in blood cultures reported after the patient’s death. Mortality rates of necrotizing gastritis in previous reports were lower than 50%. However, such finding cannot be generalized because of a small number of studies. Most of previous reported cases of necrotizing gastritis were accompanied by sepsis with elevation of white blood cell counts. However, our case showed a decrease of leukocytes. It could be interpreted as another manifestation of sepsis.

| Ref. | Diagnosis | Risk factors | Clinical course |

| Tejas et al[17], 2017 | CT | None | Exploratory laparotomy and discharge |

| Perigela et al[18], 2014 | CT | None | Exploratory laparotomy and discharge |

| Dharap et al[19], 2003 | CT | None | Exploratory laparotomy and discharge |

| Hsing et al[20], 2019 | CT | None | Intensive unit care and intravenous antibiotics then, discharge |

| Le Scanff et al[21], 2006 | CT | Acute myeloblastic leukemia with chemotherapy | Intensive unit care and discharge |

| Iwakiri et al[22], 1999 | CT | None | Intensive unit care and discharge |

| King et al[23], 2012 | CT | Acute myeloid leukemia with chemotherapy | Intravenous antibiotics, granulocyte colony stimulating factors use, then discharge |

| Nasser et al[24], 2019 | CT | Deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Intensive unit care and intravenous antibiotics then, discharge |

| Al-Jundi et al[25], 2008 | CT | Non-small cell lung cancer | Intensive unit care and discharge |

| Loi et al[26], 2007 | CT | Chronic hepatitis B, hepatocellular carcinoma | Intensive unit care and discharge |

| Kobus et al[28], 2020 | CT | Proton pump inhibitor | Total gastrectomy and death |

There are no separate guidelines for necrotizing gastritis. However, taking the previous cases and our case together so far, we think that the best diagnostic method is abdominal CT. Endoscopy may also be considered. However, it has a risk of worsening symptoms and perforation[29]. Since necrotizing gastritis is often accompanied by sepsis, gastroscopy is a contraindication if vital sign is unstable. Thus, we do not recommend gastroscopy as a first diagnostic option for necrotizing gastritis. Exploratory laparotomy could be done for diagnosis purpose. Exploratory laparotomy pus gastrectomy might also be considered when diagnosis and treatment are required at the same time.

Necrotizing gastritis has a low incidence. It is a field that has not been well studied yet. This is the first study to report a case of necrotizing gastritis in a patient with autoimmune hepatitis. Clinicians should be aware that such rare side effect can occur. Such possibility should be suspected if a patient with autoimmune hepatitis has complaint of gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain when taking immunosuppressants.

This is the first case report of a fatal necrotizing gastritis in a patient with autoimmune hepatitis receiving azathioprine and steroid. Clinicians should be aware of such rare side effect and make close observations during immunosuppressant treatment.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Rodrigues AT S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Johnson PJ, McFarlane IG. Meeting report: International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group. Hepatology. 1993;18:998-1005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 761] [Cited by in RCA: 664] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sahebjam F, Vierling JM. Autoimmune hepatitis. Front Med. 2015;9:187-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Krawitt EL. Autoimmune hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:54-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 636] [Cited by in RCA: 604] [Article Influence: 31.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Muratori P, Granito A, Quarneti C, Ferri S, Menichella R, Cassani F, Pappas G, Bianchi FB, Lenzi M, Muratori L. Autoimmune hepatitis in Italy: the Bologna experience. J Hepatol. 2009;50:1210-1218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Curtis JJ, Galla JH, Woodford SY, Saykaly RJ, Luke RG. Comparison of daily and alternate-day prednisone during chronic maintenance therapy: a controlled crossover study. Am J Kidney Dis. 1981;1:166-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Summerskill WH, Korman MG, Ammon HV, Baggenstoss AH. Prednisone for chronic active liver disease: dose titration, standard dose, and combination with azathioprine compared. Gut. 1975;16:876-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in RCA: 250] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Czaja AJ. Safety issues in the management of autoimmune hepatitis. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2008;7:319-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Vierling JM. Diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune hepatitis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2012;14:25-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gleeson D, Heneghan MA; British Society of Gastroenterology. British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) guidelines for management of autoimmune hepatitis. Gut. 2011;60:1611-1629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kogan J, Safadi R, Ashur Y, Shouval D, Ilan Y. Prognosis of symptomatic vs asymptomatic autoimmune hepatitis: a study of 68 patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35:75-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Muratori P, Lalanne C, Barbato E, Fabbri A, Cassani F, Lenzi M, Muratori L. Features and Progression of Asymptomatic Autoimmune Hepatitis in Italy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:139-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Björnsson E, Talwalkar J, Treeprasertsuk S, Kamath PS, Takahashi N, Sanderson S, Neuhauser M, Lindor K. Drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis: clinical characteristics and prognosis. Hepatology. 2010;51:2040-2048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 399] [Cited by in RCA: 343] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lewis JH, Zimmerman HJ. Drug-induced autoimmune liver disease. In: Krawitt EL WR, Nishioka K, eds. Autoimmune Liver Diseases 1998: 627-649. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312463401_Drug induced_autoimmune_liver_disease. |

| 14. | Liu ZX, Kaplowitz N. Immune-mediated drug-induced liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2002;6:755-774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Connell WR, Kamm MA, Ritchie JK, Lennard-Jones JE. Bone marrow toxicity caused by azathioprine in inflammatory bowel disease: 27 years of experience. Gut. 1993;34:1081-1085. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 363] [Cited by in RCA: 353] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Teich N, Mohl W, Bokemeyer B, Bündgens B, Büning J, Miehlke S, Hüppe D, Maaser C, Klugmann T, Kruis W, Siegmund B, Helwig U, Weismüller J, Drabik A, Stallmach A; German IBD Study Group. Azathioprine-induced Acute Pancreatitis in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases--A Prospective Study on Incidence and Severity. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:61-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tejas AP, Rajagopalan S, Rohit K. Necrotizing gastritis: a case report. Int J Surg. 2017;4:3535. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Perigela H, Vasamsetty M, Bangi V, Nagabhushigari S. Gastric gangrene due to acute necrotizing gastritis. J Dr NTR Univ Health Sci. 2014;3:38-40. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dharap SB, Ghag G, Biswas A. Acute necrotizing gastritis. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2003;22:150-151. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Hsing LC, Jung KW. Emphysematous Gastritis with Concomitant Portal Venous Air in a Healthy Woman. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2019;74:239-241. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Le Scanff J, Mohammedi I, Thiebaut A, Martin O, Argaud L, Robert D. Necrotizing gastritis due to Bacillus cereus in an immunocompromised patient. Infection. 2006;34:98-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Iwakiri Y, Kabemura T, Yasuda D, Okabe H, Soejima A, Miyagahara T, Okadome K. A case of acute phlegmonous gastritis successfully treated with antibiotics. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;28:175-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | King AJ, Eyre T, Rangarajan D, Sampson R, Grech H. Acute isolated transmural neutropenic gastritis. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:e1-e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Nasser H, Ivanics T, Leonard-Murali S, Shakaroun D, Woodward A. Emphysematous gastritis: A case series of three patients managed conservatively. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2019;64:80-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Al-Jundi W, Shebl A. Emphysematous gastritis: Case report and literature review. Int J Surg. 2008;6:e63-e66. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Loi TH, See JY, Diddapur RK, Issac JR. Emphysematous gastritis: a case report and a review of literature. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2007;36:72-73. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Ko GJ, Park KS, Park TW, Woo MY, Han KJ, Lee SC, Cho JH. [A case of emphysematous gastritis in a patient with end-stage renal disease]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2011;58:38-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kobus C, van den Broek JJ, Richir MC. Acute gastric necrosis caused by a β-hemolytic streptococcus infection: a case report and review of the literature. Acta Chir Belg. 2020;120:53-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Chirica M, Champault A, Dray X, Sulpice L, Munoz-Bongrand N, Sarfati E, Cattan P. Esophageal perforations. J Visc Surg. 2010;147:e117-e128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |