Published online May 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i14.3466

Peer-review started: December 15, 2020

First decision: January 17, 2021

Revised: January 27, 2021

Accepted: March 15, 2021

Article in press: March 15, 2021

Published online: May 16, 2021

Processing time: 135 Days and 5.1 Hours

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome (CCS) is a rare nonhereditary disease characterized by chronic diarrhoea, diffuse gastrointestinal polyposis and ectodermal manifestations. The lethality of CCS can be up to 50% if it is untreated or if treatment is delayed or inadequate. More than 35% of the patients do not achieve long-term clinical remission after corticosteroid administration, with relapse occurring during or after the cessation of glucocorticoid use. The optimal strategy of maintenance therapy of this disease is controversial.

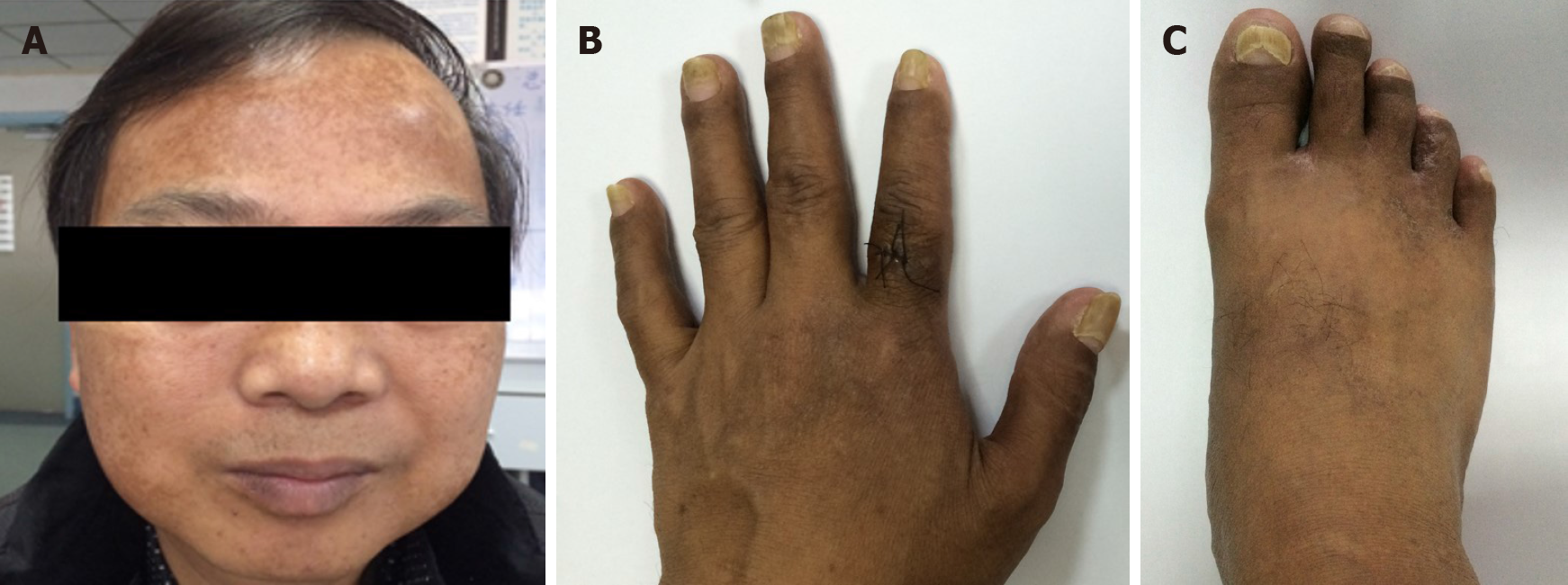

A 47-year-old man presented to the hospital with a 3-mo history of frequent watery diarrhoea, accompanied by macular skin pigmentation that included the palms and soles, and onychodystrophy of the fingernails and toenails. Gastroscopy and colonoscopy revealed numerous polyps in the stomach and colon. After other possibilities were ruled out by a series of examinations, CCS was diagnosed and treated with prednisone. The patient took prednisone for more than 1 year before achieving complete resolution of his symptoms and endoscopic findings. The patient was then given prednisone 5 mg/d for 6 mo of maintenance therapy. With clinical improvement and polyp regression, prednisone was discontinued. Eight mo after the discontinuation of prednisone, the diarrhoea and gastrointestinal polyps relapsed. Therefore, the patient was given the same dose of prednisone, and complete remission was achieved again.

It is necessary to extend the duration of prednisone maintenance therapy for CCS. Prednisone is still effective when readministered after relapse. Surveillance endoscopy at intervals of 1 year or less is recommended to assess mucosal disease activity.

Core Tip: Cronkhite-Canada syndrome (CCS) is a rare gastrointestinal polyposis syndrome. Here, we report a case of CCS that has been followed for almost 4 years. The patient was treated with prednisone. After he discontinued prednisone, his clinical and endoscopic manifestations relapsed. The patient was given prednisone again, and it was effective in bringing about a second remission. It is necessary to extend the duration of prednisone maintenance therapy for CCS. Surveillance endoscopy at intervals of 1 year or less is recommended to assess mucosal disease activity.

- Citation: Jiang D, Tang GD, Lai MY, Huang ZN, Liang ZH. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome with steroid dependency: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(14): 3466-3471

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i14/3466.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i14.3466

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome (CCS) is a rare gastrointestinal polyposis syndrome characterized by dermatologic manifestations associated with chronic diarrhoea, malnutrition, and enteric protein wasting resulting from chronic inflammatory changes in the intestinal mucosa[1-3]. Since the disease was first described in 1955, only approximately 500 patients with CCS have been reported worldwide, among which over 70% were from Japan[2,4,5]. Although disease presentation has been well described, there is no consensus on the management of CCS. Its clinical course is characterized by progressive disease with occasional spontaneous remissions and frequent relapses[6]. The lethality of CCS can be up to 50% if it is untreated or if treatment is delayed or inadequate. The 5-year mortality of CCS patients can be as high as 55% secondary to complications[7].

A 47-year-old Chinese man presented to the hospital with frequent watery diarrhoea.

The patient had no history of prior illness and no family history of any similar disease.

The patient’s symptoms had started 3 mo prior with frequent watery diarrhoea (4-5 times/d). For nearly a month, there was apparent blood in the diarrhoea and positive faecal occult blood with acid regurgitation, eructation, occasional nausea, and a weight loss of 10 kg within 2 mo. The patient was treated with symptomatic therapies, such as spasmolytics and antibiotics, which were ineffective in alleviating his symptoms.

The patient had no history of prior illness and no family history of any similar disease.

A physical examination revealed marked alopecia; brownish macular pigmentation of the facial region, palms and soles; and onychodystrophy of the fingernails and toenails (Figure 1).

The laboratory findings included a positive faecal occult blood showing 0-2 red blood cells/haptoglobin, an albumin concentration of 32.7 g/L (normal range 40-55 g/L), and cytoplasmic antinuclear antibody positivity with a titre of 1:320.

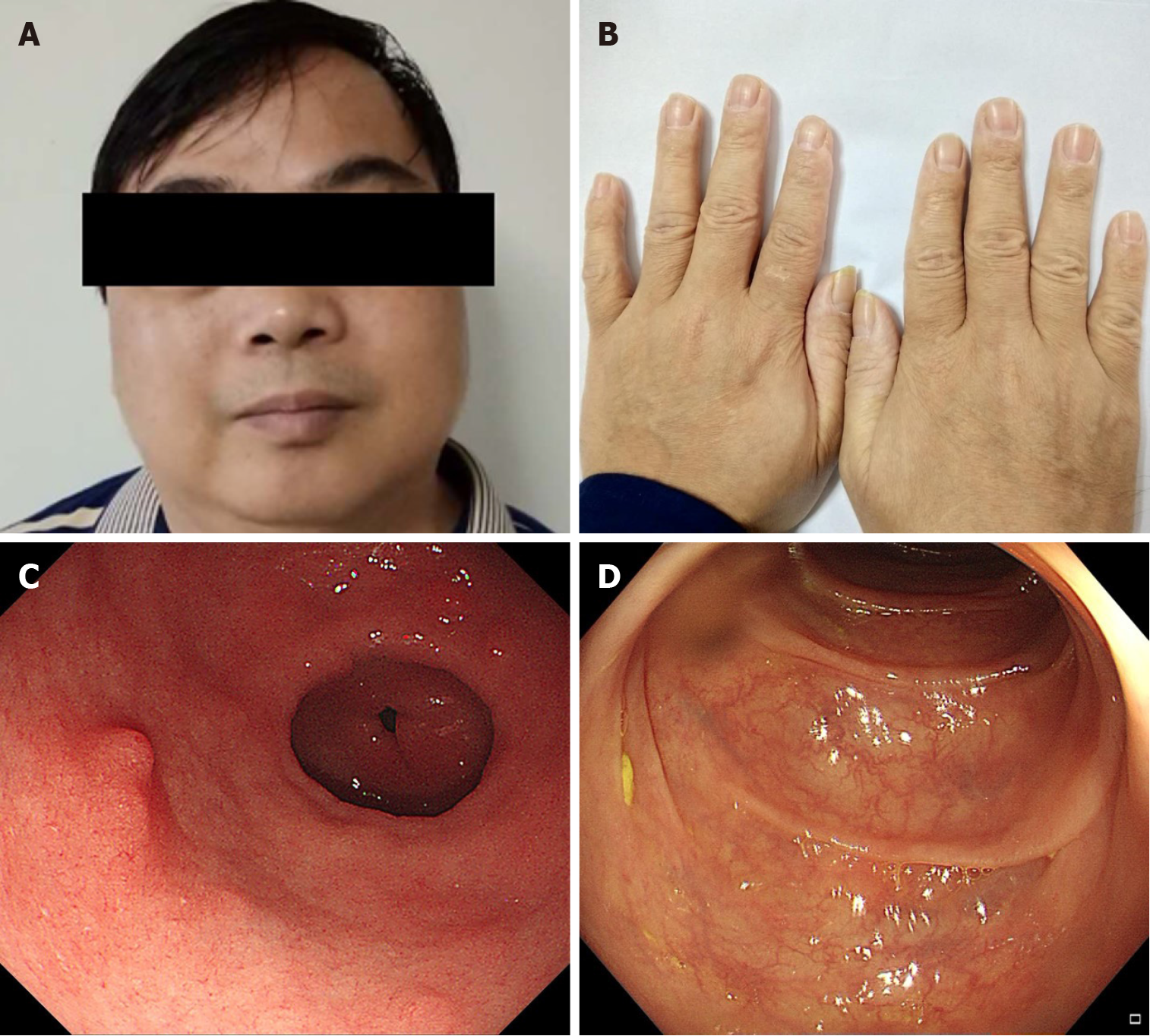

Gastroscopy revealed multiple polyps in the stomach and duodenum (Figure 2A). Endoscopic ultrasonography revealed diffuse thickening of the gastric mucosa to 8.5 mm (i.e. massive enlargement of the mucosa and submucosa), and the polyps originated from the mucosa, which was internally hyperechoic and inhomogeneous (Figure 2B). Colonoscopy revealed numerous polyps occupying the colonic and rectal mucosa (Figure 2C).

Histological examination of biopsy specimens obtained from the colon and the stomach was consistent with hyperplastic polyps, and immunoglobulin G 4 staining was negative.

The final diagnosis of the present case was CCS.

Oral administration of prednisone was initiated at 40 mg/d, and the daily steroid dose was varied in a tapered regimen, with a decrease of 5 mg every 4 wk.

After 3 mo of treatment, the gastrointestinal symptoms and ectodermal manifestations began disappearing one-by-one, and gastrointestinal endoscopy showed small, sparsely distributed polyps. After 6 mo of treatment, the patient’s skin colour was normal and his nail dystrophy was improved (Figure 3A and B). Gastroscopy and colonoscopy showed that the polyps were significantly reduced in size and number. However, the patient’s gastrointestinal manifestations relapsed, including diarrhoea; in response, we slowed the prednisone reduction, subtracting 5 mg from the daily dose only once every 3-6 mo. Until April 2018, the patient took only 5 mg of prednisone a day. After 14 mo of treatment, he was admitted to our hospital again for follow-up. The faecal occult blood test was negative; serum albumin levels had risen to normal. Additionally, the tumour markers were negative. Gastroscopy revealed several polyps with a diameter of 3-4 mm in the gastric antrum and duodenum. Some of the polyps were removed by endoscopic mucosal resection (Figure 3C). Colonos

Eight mo after the discontinuation of prednisone, the patient developed ectodermal manifestations again and was reviewed by gastroscopy, which suggested a relapse of CCS. We began to treat the patient again with the original regimen (i.e. a dose of 40 mg prednisone qd po with a decrease of 5 mg every 4 wk). Prednisone was reduced to 10 mg/d and maintained for 6 mo. In October 2020, we reviewed the patient by gastroscopy and colonoscopy, which indicated that the mucosal lesions had disappe

CCS is a rare disease, and there is no consensus on therapy at present. Treatment for CCS is largely based on anecdotal evidence and traditionally consists of nutritional support, histamine receptor antagonists, steroids, immunosuppression, or Helicobacter pylori eradication. A retrospective analysis has confirmed that steroid therapy is the mainstay of medical treatment and that 30-49 mg/d of orally administered prednisolone is optimal for active CCS, suggesting that the prednisolone dose should be slowly tapered only after endoscopic confirmation of the regression of polyposis[2]. The duration of therapy usually required is 6-12 mo. Once a sustained response is achieved, corticosteroids should be slowly tapered and eventually discontinued. Recurrences often respond to corticosteroid retreatment[8]. More than 35% of patients failed to achieve long-term clinical remission after corticosteroid administration, and relapse occurred during or after the cessation of glucocorticoid use. A proportion of patients were prescribed low-dose (5-10 mg/d) corticosteroids or immuno-suppressants to counteract the tendency to relapse[5].

As immunological dysregulation is one of the important factors hypothesized to be present in CCS, the long-term use of immunoregulatory drugs or biologics may be useful for active or refractory disease[9]. Steroid-sparing therapies such as cyclosporine A and an antitumor necrosis factor- agent, a combination that has shown promise in a few cases, can be used in steroid-resistant cases to induce or maintain clinical remission. Other case reports described the beneficial response of immunosuppressive therapies including infliximab, sirolimus, tacrolimus, methicillin, and mycophenolate mofetil[2,10-14]. Azathioprine and mesalazine used with steroid maintenance therapy were reported to be associated with sustained clinical remission[3,15-17]. In a study by Mao et al[17], the patient was given a dose of 1.25 mg/kg/d azathioprine (previous reports had specified a dose of 2 mg/kg/d). The prednisone dose was tapered after 6 wk of therapy, and azathioprine was initiated. Corticosteroid side effects resolved when the prednisone was tapered, and CCS symptoms remained controlled on azathioprine without adverse effects; the total course of treatment consisted of 6 wk of prednisone and 26 wk of azathioprine. In a study by Schulte et al[3], discontinuation of steroid therapy was not possible, and mesalazine (1000 mg tid) was added to prednisolone (10.0 mg/d). The steroid dosage was further reduced over the course of 3 years; when all polyps had disappeared and the steroid therapy was finished, the dosage of mesalazine was reduced in a stepwise fashion. Four years later, the mesalazine was stopped, and more than 14.0 years after the initial diagnosis, the patient was still in complete remission without any treatment.

In conclusion, the mainstay of medical treatment for CCS is steroid therapy. Endoscopic remission and histopathologic remission are the therapeutic goals. A standard dose-adjustment protocol for prednisolone in CCS patients has not been established. Prednisone treatment after relapse in this case is still effective. Treatment should, therefore, be individualized for each patient according to their symptoms and recorded response to previous therapy. In episodically active clinical disease, the frequent use of steroids is necessary to prevent endoscopic relapse. Azathioprine, mesalazine, and other drugs merit consideration as CCS maintenance therapy. Surveillance endoscopy at intervals of 1 year or less is recommended to assess mucosal disease activity.

Steroid therapy is the mainstay of medical treatment for CCS. Endoscopic remission and histopathologic remission are the therapeutic goals. In the current case, prednisone treatment was still effective after relapse. Treatment should, therefore, be individualized for each patient according to his or her symptoms and recorded responses to previous therapy. Surveillance endoscopy at intervals of 1 year or less is recommended to assess mucosal disease activity.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: de Nucci G S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Slavik T, Montgomery EA. Cronkhite–Canada syndrome six decades on: the many faces of an enigmatic disease. J Clin Pathol. 2014;67:891-897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Watanabe C, Komoto S, Tomita K, Hokari R, Tanaka M, Hirata I, Hibi T, Kaunitz JD, Miura S. Endoscopic and clinical evaluation of treatment and prognosis of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: a Japanese nationwide survey. J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:327-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Schulte S, Kütting F, Mertens J, Kaufmann T, Drebber U, Nierhoff D, Töx U, Steffen HM. Case report of patient with a Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: sustained remission after treatment with corticosteroids and mesalazine. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19:36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zong Y, Zhao H, Yu L, Ji M, Wu Y, Zhang S. Case report-malignant transformation in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome polyp. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e6051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Liu S, You Y, Ruan G, Zhou L, Chen D, Wu D, Yan X, Zhang S, Zhou W, Li J, Qian J. The Long-Term Clinical and Endoscopic Outcomes of Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2020;11:e00167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ward E, Wolfsen HC, Ng C. Medical management of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. South Med J. 2002;95:272-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Daniel ES, Ludwig SL, Lewin KJ, Ruprecht RM, Rajacich GM, Schwabe AD. The Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome. An analysis of clinical and pathologic features and therapy in 55 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1982;61:293-309. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Ward EM, Wolfsen HC. Pharmacological management of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2003;4:385-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bettington M, Brown IS, Kumarasinghe MP, de Boer B, Bettington A, Rosty C. The challenging diagnosis of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome in the upper gastrointestinal tract: a series of 7 cases with clinical follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:215-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ohmiya N, Nakamura M, Yamamura T, Yamada K, Nagura A, Yoshimura T, Hirooka Y, Matsumoto T, Hirata I, Goto H. Steroid-resistant Cronkhite-Canada syndrome successfully treated by cyclosporine and azathioprine. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48:463-464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yamakawa K, Yoshino T, Watanabe K, Kawano K, Kurita A, Matsuzaki N, Yuba Y, Yazumi S. Effectiveness of cyclosporine as a treatment for steroid-resistant Cronkhite-Canada syndrome; two case reports. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;16:123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Langevin C, Chapdelaine H, Picard JM, Poitras P, Leduc R. Sirolimus in Refractory Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome and Focus on Standard Treatment. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2018;6:2324709618765893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Taylor SA, Kelly J, Loomes DE. Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome: Sustained Clinical Response with Anti-TNF Therapy. Case Rep Med. 2018;2018:9409732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Liu Y, Zhang L, Yang Y, Peng T. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: report of a rare case and review of the literature. J Int Med Res. 2020;48:300060520922427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Takakura M, Adachi H, Tsuchihashi N, Miyazaki E, Yoshioka Y, Yoshida K. A case of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome markedly improved with mesalazine therapy. Dig Endosc. 2004;16:74-78. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Flannery CM, Lunn JA. Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome: an unusual finding of gastro-intestinal adenomatous polyps in a syndrome characterized by hamartomatous polyps. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2015;3:254-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mao EJ, Hyder SM, DeNucci TD, Fine S. A Successful Steroid-Sparing Approach in Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome. ACG Case Rep J. 2019;6:1-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |