Published online Apr 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i7.1311

Peer-review started: December 1, 2019

First decision: December 23, 2019

Revised: January 13, 2020

Accepted: March 9, 2020

Article in press: March 9, 2020

Published online: April 6, 2020

Processing time: 126 Days and 15.6 Hours

The incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in pregnant women is significantly higher than that in non-pregnant women. VTE is more common after delivery than before delivery, and this condition can be hidden and develops rapidly. VTE mainly includes deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Thrombophilia is an important risk factor for VTE in pregnant women and includes acquired thrombophilia and hereditary thrombophilia.

A 24-year-old nulliparous female patient underwent cesarean section of the lower uterus due to fetal distress. Anti-inflammatory rehydration was given after the operation to prevent thrombosis. The patient had no obvious discomfort after surgery. Ten days after the operation, the patient developed a fever. The patient's mother revealed that she had a previous history of a lower extremity venous thrombosis. Color Doppler ultrasound showed deep vein thrombosis in the left lower extremity. The results of computed tomography angiography showed that the patient had a double pulmonary artery embolism. Bilateral lower extremity antegrade venography, inferior vena cava angiography and filter placement were performed. The patient continued to receive anticoagulant therapy. After 2 wk, the patient's condition improved. An anticoagulant protein test was performed 2 mo after discharge, and the results showed that both the patient and her mother had reduced protein S.

Clinicians should learn to recognize the high-risk factors for VTE, improve their understanding of VTE, and actively prevent and diagnose VTE as early as possible.

Core tip: Thrombophilia is an important risk factor for venous thromboembolism (VTE) in pregnant women. We present herein, a rare case of severe VTE caused by thrombophilia in the puerperium period. The severe VTE in this patient with a family history of lower extremity venous thrombosis developed rapidly into pulmonary embolism, but the clinical symptoms were not typical, and the diagnosis was confirmed by ultrasonography and pulmonary computed tomography angiography. This case demonstrates that clinicians should learn to recognize the high risk factors for VTE, and improve their understanding of thrombophilia during pregnancy and puerperium.

- Citation: Zhang J, Sun JL. Severe venous thromboembolism in the puerperal period caused by thrombosis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(7): 1311-1318

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i7/1311.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i7.1311

More than 80% of thromboembolic diseases in pregnant women are venous thromboembolism (VTE), and the prevalence of VTE is significantly higher in pregnant women than in non-pregnant women[1]. VTE mainly includes deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE). In total, 50% of VTE occurs in the puerperium, especially 7 d after childbirth. The disease is highly insidious, develops rapidly and seriously endangers the health and life of the mother. VTE is one of the most common critical illnesses in obstetrics[2]. Thrombophilia is an important risk factor for VTE in pregnant women. In patients with VTE during pregnancy, 20%-50% have thrombophilia, and both acquired thrombophilia and hereditary thrombophilia can increase the risk of pregnancy VTE. This article reports a case of severe VTE caused by thrombophilia in the puerperium in combination with a literature review to highlight the risk factors, diagnosis, treatment and prevention of the disease.

A 24-year-old delivery woman who had undergone a cesarean section presented to our hospital complaining of a fever.

The patient who was pregnant for the first time had no abnormalities during the pregnancy. On March 28, 2019, the patient underwent cesarean section of the lower uterus due to fetal distress. The operation was successful, and anti-inflammatory rehydration and other treatments were given after the operation to promote uterine contractions and prevent thrombosis (low-molecular-weight heparin calcium 5000 IU/d subcutaneous injection). The patient had no obvious discomfort after surgery and was discharged on April 2, 2019. On April 9, 2019, the patient developed a fever. She had no discomfort such as cough, expectoration, or frequency or urgency of urination. Her breasts were slightly swollen and tender, and her lactation and lochia were normal.

The patient had a family history of lower extremity venous thrombosis.

At 15:42 on April 9, 2019, physical examination results were as follows: Body temperature: 39.8°C, pulse rate: 133 beats/min, respiratory rate: 18 breaths/min, blood pressure: 116/81 mmHg, no anemia, no obvious abnormality on cardio-pulmonary auscultation, entire abdomen was soft, no tenderness, no obvious mass, bilateral symmetrical lower limbs, no swelling, no varicose veins, normal skin color, and normal skin temperature without tenderness. A specialist examination found no redness or swelling at the incision and no concentrated secretions. Physical examination on April 10, 2019 revealed the following: Body temperature: 37.8 °C, pulse rate: 118 beats/min, and no obvious abnormalities on cardiopulmonary auscultation. Her breasts were slightly swollen and tender, and her lactation was smooth; no nodules were detected, the whole abdomen was soft, and there was no tenderness and no obvious mass. The appearance of the lower limbs was symmetrical, with no varicose veins, and the skin color and palpation skin temperature were normal. The patient complained of soreness in the left groin at 12:30.

At 15:42 on April 9, 2019, routine blood tests showed a white blood cell count of 15.02 × 109/L and a C-reactive protein level of 139.24 mg/L. Laboratory examination on April 10, 2019 revealed the following: A white blood cell count of 12.40 × 109/L, and a C-reactive protein level of 166.89 mg/L. There were no obvious abnormalities on routine examination of the urine, liver, kidney, and vaginal discharge. Routine blood examination on April 11, 2019 revealed the following: A white blood cell count of 8.97 × 109/L, and a C-reactive protein level of 160.91 mg/L.

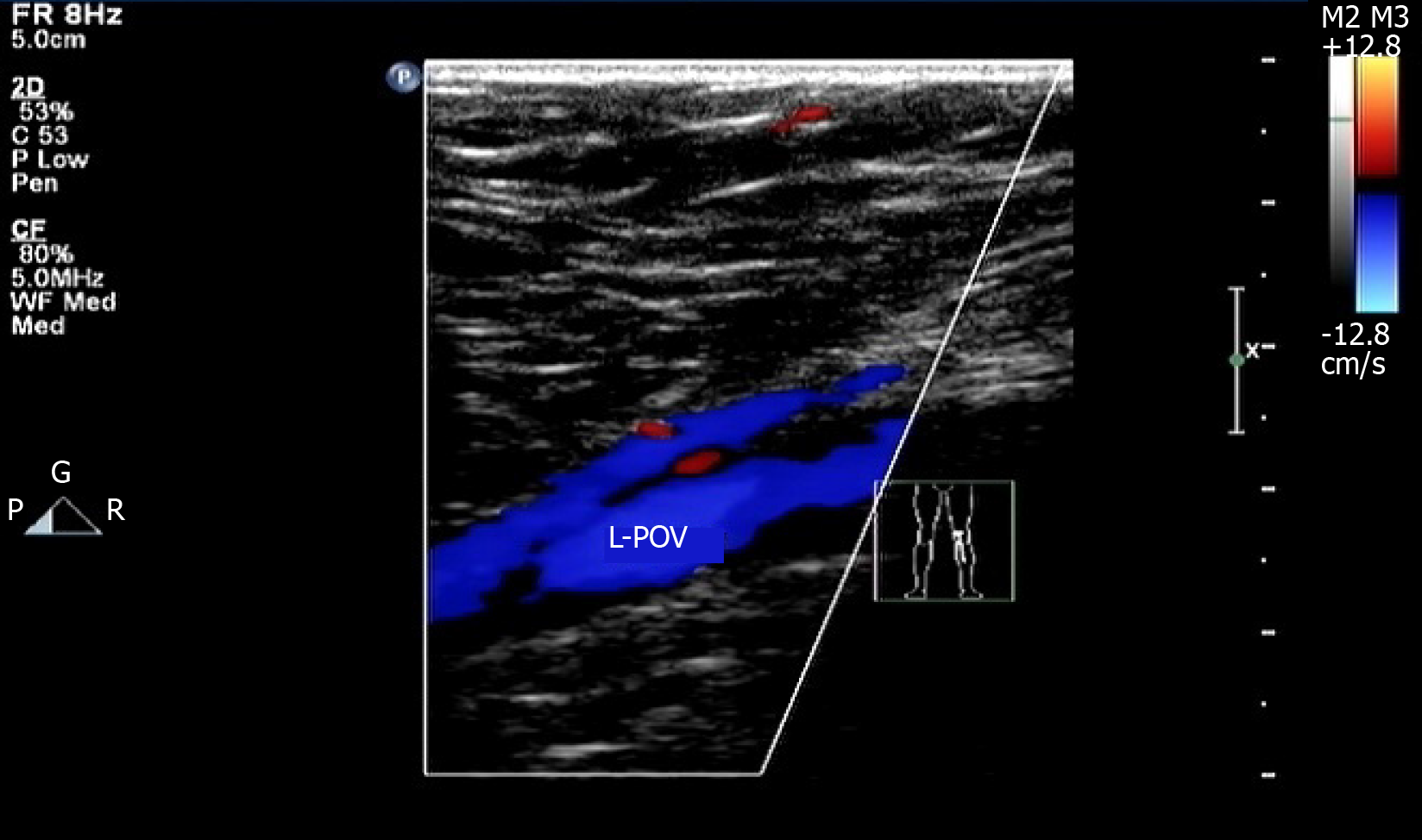

On April 11, 2019, a chest computed tomography (CT) scan showed a mild infection of the lower lungs. Color Doppler ultrasound showed a thrombosis in the left saphenous vein in the thigh segment, external iliac vein, total femoral vein, femoral deep vein, and superficial femoral vein (acute phase and central type), as shown in Figure 1.

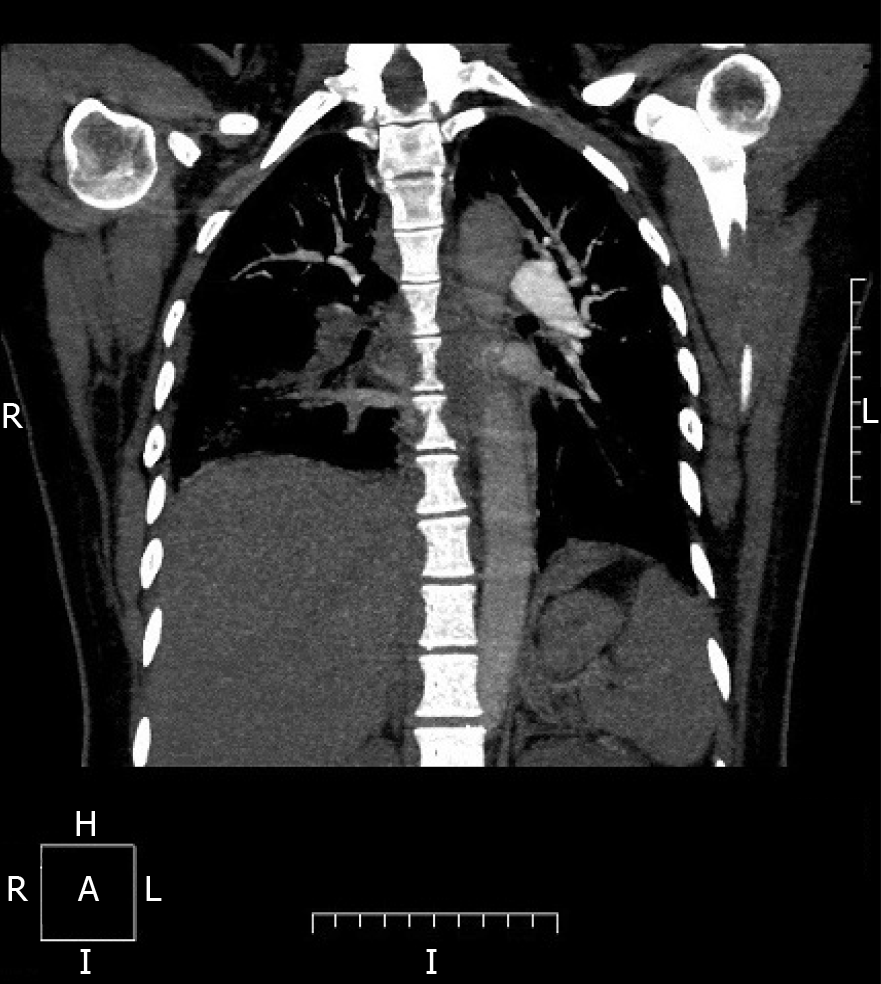

The patient was diagnosed with DVT in the left lower extremity and was given plasma D-dimer 47.24 μg/mL. Due to the possibility of PE as a result of exfoliation of the thrombus at any time, we recommended that the patient be treated with thrombolysis following the placement of an inferior vena cava filter, but the patient refused and chose to continue conservative treatment. The affected limb was immobilized and raised by 20 degrees. Diosmin tablets 0.9 g, twice daily and rivaroxaban tablets 10 mg/d were administered orally, and subcutaneous injections of low molecular weight heparin calcium 5000/day were also administered as continuous anti-inflammatory treatment. Physical examination on April 12, 2019 revealed the following: body temperature 37.6°C, pulse rate 86 beats/min, blood pressure 99/73 mmHg, measurement of the left thigh circumference at the same fixed position was 61 cm, calf circumference was 40 cm, right thigh circumference was 60 cm, and calf circumference was 40 cm. It was observed that the lower limbs were basically symmetrical, with no obvious swelling and normal skin color, and the skin temperature of the left lower limb was slightly higher than that of the right lower limb. On April 13, 2019, the patient complained of pain in the right axillary area. No difficulty in breathing, no chest tightness or chest pain, no hemoptysis, and no pain in the anterior region were observed. Physical examination revealed the following: blood oxygen saturation of 94%, and oxygen partial pressure of 60 mmHg. At 23:11, the results of CT angiography showed that the patient had a double pulmonary artery embolism, and the right lower lung was more pronounced than the left lower lung, as shown in Figure 2.

The final diagnosis was severe VTE in the puerperal period caused by thrombosis.

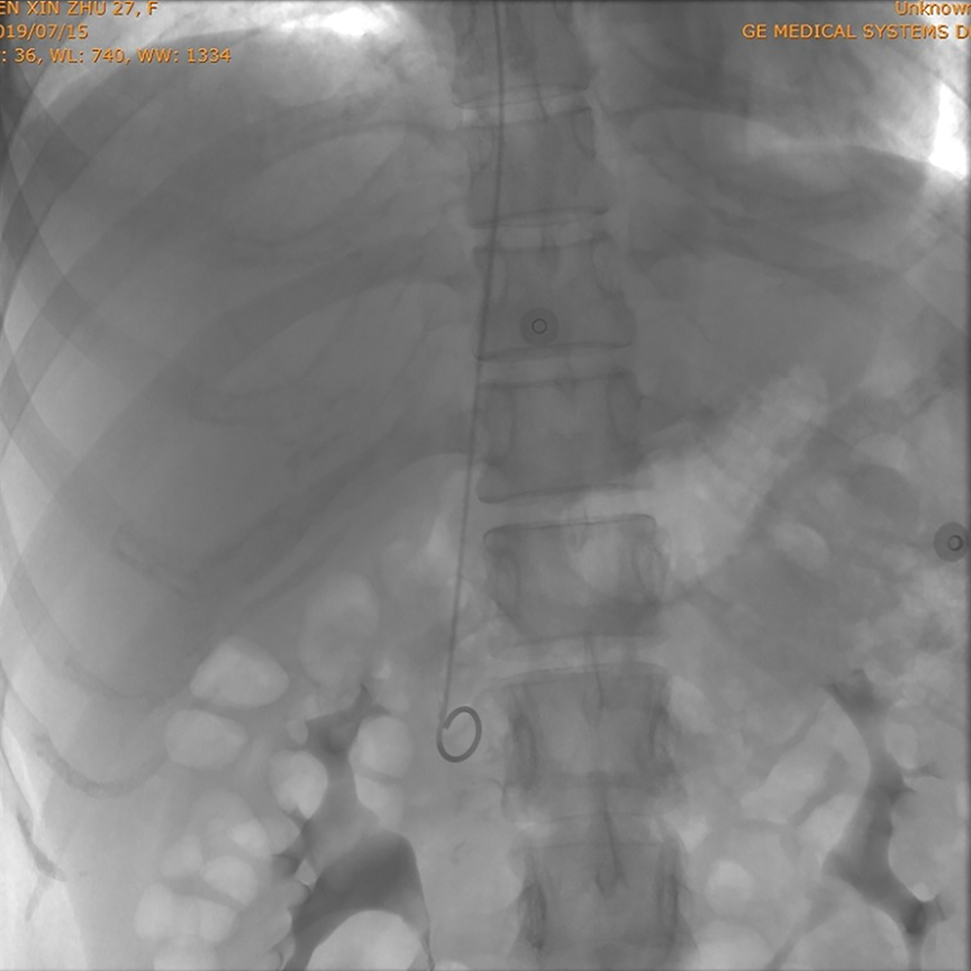

Following preoperative preparation of the patient, on April 16, 2019, bilateral lower extremity antegrade venography, inferior vena cava angiography and filter placement were performed, as shown in Figure 3. The patient continued to receive anticoagulant therapy, oral rivaroxaban tablets 10 mg/d, and subcutaneous injections of low molecular weight heparin calcium 5000/d.

After 2 wk, the patient's condition improved, and she was discharged. An anticoagulant protein test was performed 2 mo after discharge, and the results showed that both the patient and her mother had reduced protein S.

Thrombophilia, also known as a prethrombotic state, is not a single clinical disease but refers to a pathophysiological process that makes the patient prone to thromboembolism due to hereditary or acquired defects or the presence of acquired risk factors; thrombophilia can be divided into hereditary thrombophilia and acquired thrombophilia[3]. Hereditary thrombophilia refers to an increased risk of thrombosis due to persistent hypercoagulability caused by congenital reasons or genetic mutations[4].

Acquired thrombophilia is a condition where thromboembolisms are prone to occur due to acquired risk factors. These risk factors include pregnancy and the postpartum period, surgery, postoperative hemostatic drugs, advanced age, smoking, obesity, prolonged bed rest or immobilization, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, malignant tumors, chronic wasting disease, abnormal lipid metabolism, high blood pressure, etc. Thrombophilia can affect the body's arteries and veins due to imbalances in the coagulation-anticoagulant mechanisms or fibrinolytic activity, leading to thrombosis[3]. If the thrombus is mainly venous thrombosis, then the condition is known as VTE.

VTE refers to blood circulation disorders caused by the obstruction of veins due to the formation of emboli caused by the abnormal agglomeration of blood in the venous lumen. VTE includes DVT (approximately 75%), PE (approximately 20%), pelvic venous thrombosis and intracranial venous sinus thrombosis (approximately 5%). Most of the thrombi causing PE arise from DVT and are considered to be one of the signs of PE. Due to special physiological changes during pregnancy, blood clotting factors increase, and secondary physiologic hypercoagulability is one of the most important acquired risk factors for thrombophilia during pregnancy[5]. If there are other simultaneous high-risk factors, a thrombotic event is more likely. The incidence of VTE in pregnant women is relatively high, the probability of maternal VTE is approximately 5 times that for non-pregnant women, and the incidence of maternal VTE after cesarean delivery is approximately 10 times that after normal vaginal delivery[6]. VTE during pregnancy is a serious obstetric complication that is very harmful to maternal health; especially PE caused by detached emboli, the probability of maternal death is very high. Half of all maternal VTE occur during pregnancy, and half occur during the puerperium, especially during the first week after birth[7]. In recent years, the incidence of VTE during pregnancy has increased.

The sites of DVT in pregnant women is usually the left lower limb, of which 64% are iliac vein emboli, and 17% are venous emboli[8]. The clinical symptoms mainly include sudden limb swelling, pain, increased soft tissue tension, and exacerbation of bulging or fever after activity[9]. Raising the affected limb during physical examination can alleviate the symptoms, and the site of the venous thrombosis is often tender. Positive Homans and Neuhof signs are observed, and most of the symptoms are mild. When the leg circumference of the two legs differs by 2 cm or more, the possibility of DVT of the lower extremity is high[10]. When the symptoms or signs suggest DVT, the initial diagnosis can be made using compression vascular ultrasound of the proximal vein. If the results of the compression vascular ultrasound are negative or suspicious and the clinical symptoms indicate suspected iliac vein thrombosis, Doppler ultrasonography, venography, or magnetic resonance imaging of the iliac vein are recommended[11]. A negative plasma D-dimer test can exclude DVT, but this test lacks specificity. Moreover, considering the high physiological D-dimer level in females during pregnancy, this marker is of little significance for the diagnosis of DVT. Therefore, D-dimer alone is not recommended as an indicator for the evaluation of DVT during pregnancy or the puerperium[12]. The clinical manifestations of PE lack specificity, and patients can be completely asymptomatic, which is known as "asymptomatic PE". If the patient has chest pain, shortness of breath, wheezing, and bruising, the possibility of PE should be considered. The diagnosis of new maternal PE is similar to that of PE in non-pregnant patients. CT angiography is reco-mmended[13].

Following a clear diagnosis of VTE, patients should be treated immediately. Low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) has a longer half-life than unfractionated heparin, is safer, does not pass through the placental barrier and is not teratogenic[14]. There are data showing that after treatment with LMWH, patients with VTE during pregnancy have a recurrence rate of 1.15%, a mortality rate of 0%, and a major bleeding rate of 1.72%, suggesting that LMWH is safe and effective for the prevention and treatment of VTE during pregnancy[15]. Warfarin is often used for long-term anticoagulant therapy during non-pregnancy but can potentially damage the fetus[16]. In 2015, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists' Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Venous Thromboembolic Diseases in Pregnancy and Postpartum Period indicated that LMWH is recommended instead of warfarin for pregnant women who need long-term anticoagulant therapy. However, for pregnant women with mechanical heart valves, the risk of thrombosis is still higher with heparin or LMWH anticoagulant therapy than with warfarin; thus the continued use of warfarin anticoagulation should be considered[17]. The safety of oral thrombin inhibitors (dabigatran) and anti-Xa inhibitors (rivaroxaban) on fetal and neonatal development and the relationship of these drugs with fetal teratogenesis are unclear. These drugs are secreted through the breast milk and can be detected in breast milk, so these inhibitors should be avoided during pregnancy and lactation[18] (Table 1).

| Basic data | Before admission and systemic anticoagulant therapy | After systemic anticoagulant therapy and before discharge |

| Body temperature | 39.3 °C | 36.5 °C |

| Heart rate | 114 beats/min | 85 beats/min |

| Blood pressure | 118/80 mmHg | 110/76 mmHg |

| Blood oxygen saturation (no oxygen inhalation) | 94% | 100% |

| White blood cell count | 15.02 × 109/L | 7.15 × 109/L |

| C-reactive protein | 139.24 mg/L | 2.30 mg/L |

| Hemoglobin | 76 g/L | 107 g/L |

| Platelets | 525 × 109/L | 436 × 109/L |

| D-dimer | 47.24 µg/mL | 8.66 µg/mL |

| Fibrinogen | 7.83 | 3.96 g/L |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time | 46.8 s | 30.5 s |

| Prothrombin time | 17.7 s | 19.5 s |

Hereditary thrombophilia increases the risk of thromboembolic disease during pregnancy. Although there is no consistent evidence of the benefits of screening and treatment during pregnancy, due to these adverse outcomes, clinically, there is still a tendency to screen for hereditary thrombophilia in high-risk groups. Screening is recommended in the following situations: (1) History of thrombosis associated with nonrecurring risk factors (such as fractures, surgery, and long-term immobilization); and (2) First-degree relatives (parents or siblings) who are at high risk of thrombophilia. Laboratory screening should be performed 6 wk after the thrombotic event and should be performed during non-pregnancy without anticoagulation or hormonal therapy[19].

This patient had severe VTE during the puerperium, and fever was the main symptom of DVT of the lower extremity. There were no other clinical manifestations when the DVT was diagnosed by ultrasound 48 h after admission. Despite active anticoagulant therapy and immobilization, the patient rapidly developed a PE. At this time, there were no typical symptoms, such as difficulty breathing or hemoptysis. She only showed mild pain in the infraorbital area and had normal vital signs, especially blood oxygen saturation. The patient was diagnosed by CT angiography, which was consistent with the description of “asymptomatic PE”.

(1) The doctor's inquiry about her medical history was not rigorous or meticulous, thus missing the previous history of a lower extremity venous thrombosis that occurred after delivery in the patient’s mother; (2) The doctor was relatively unfamiliar with atypical VTE and lacked clinical experience; clinical symptoms in this patient only consisted of a fever; and (3) The patient's condition was concealed; however, the disease developed extremely rapidly. Initially, only DVT of the lower extremity was diagnosed, but then the condition rapidly developed into a PE. After analyzing the case, we found that these three main reasons affected diagnosis of the disease. In recent years, the incidence of VTE in young people has been reported to have gradually increased. Therefore, in a young patient with high-risk factors, VTE should also be considered. Our patient had a clear genetic predisposition. Both the patient and her mother had reduced protein S levels, which is considered to be indicative of hereditary thrombophilia. Combined with pregnancy, her cesarean section and other reasons, her blood was in a hypercoagulable state, resulting in multiple venous thrombi in the body; the diagnosis of acquired thrombophilia was clear. The risk of venous thrombosis induced by each acquired thrombotic factor is not the same. Normally, only one thrombotic risk factor does not cause venous thrombosis, but if multiple thrombotic risk factors coexist, the risk of venous thrombosis is greatly increased. Acquired thrombophilia is often a predisposing factor for thrombotic events in patients with hereditary thrombophilia. When several acquired thrombophilia risk factors coexist, a thrombosis is more likely to occur. In summary, the etiology of thrombophilia is complex and diverse, there are different forms of the disease, and the condition is serious. Clinicians should learn to identify high-risk factors for VTE and improve their understanding of thrombosis during pregnancy and the puerperium. Active prevention, early diagnosis, and timely treatment can reduce the morbidity and mortality of patients with VTE.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cobucci RN, Kantsevoy S S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: A Webster JR E-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Creanga AA, Syverson C, Seed K, Callaghan WM. Pregnancy-Related Mortality in the United States, 2011-2013. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:366-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 543] [Cited by in RCA: 748] [Article Influence: 93.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Pomp ER, Lenselink AM, Rosendaal FR, Doggen CJ. Pregnancy, the postpartum period and prothrombotic defects: risk of venous thrombosis in the MEGA study. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:632-637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 424] [Cited by in RCA: 399] [Article Influence: 23.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 197: Inherited Thrombophilias in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e18-e34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Heit JA, Cunningham JM, Petterson TM, Armasu SM, Rider DN, DE Andrade M. Genetic variation within the anticoagulant, procoagulant, fibrinolytic and innate immunity pathways as risk factors for venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:1133-1142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Whitty JE, Dombrowski MP. Respiratory disease in pregnancy. In: Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL, Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, Driscoll DA, Berghella V, Grobman WA. Obstetrics: Normal and problem pregnancies. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier 2017; 828-849. |

| 6. | Pabinger I, Grafenhofer H, Kyrle PA, Quehenberger P, Mannhalter C, Lechner K, Kaider A. Temporary increase in the risk for recurrence during pregnancy in women with a history of venous thromboembolism. Blood. 2002;100:1060-1062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Croles FN, Nasserinejad K, Duvekot JJ, Kruip MJ, Meijer K, Leebeek FW. Pregnancy, thrombophilia, and the risk of a first venous thrombosis: systematic review and bayesian meta-analysis. BMJ. 2017;359:j4452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chan WS, Spencer FA, Ginsberg JS. Anatomic distribution of deep vein thrombosis in pregnancy. CMAJ. 2010;182:657-660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | James AH, Tapson VF, Goldhaber SZ. Thrombosis during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:216-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chan WS, Lee A, Spencer FA, Crowther M, Rodger M, Ramsay T, Ginsberg JS. Predicting deep venous thrombosis in pregnancy: out in "LEFt" field? Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:85-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bates SM, Jaeschke R, Stevens SM, Goodacre S, Wells PS, Stevenson MD, Kearon C, Schunemann HJ, Crowther M, Pauker SG, Makdissi R, Guyatt GH. Diagnosis of DVT: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e351S-e418S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 487] [Cited by in RCA: 434] [Article Influence: 33.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Van der Pol LM, Mairuhu AT, Tromeur C, Couturaud F, Huisman MV, Klok FA. Use of clinical prediction rules and D-dimer tests in the diagnostic management of pregnant patients with suspected acute pulmonary embolism. Blood Rev. 2017;31:31-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chunilal SD, Bates SM. Venous thromboembolism in pregnancy: diagnosis, management and prevention. Thromb Haemost. 2009;101:428-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Harenberg J, Schneider D, Heilmann L, Wolf H. Lack of anti-factor Xa activity in umbilical cord vein samples after subcutaneous administration of heparin or low molecular mass heparin in pregnant women. Haemostasis. 1993;23:314-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jacobson B, Rambiritch V, Paek D, Sayre T, Naidoo P, Shan J, Leisegang R. Safety and Efficacy of Enoxaparin in Pregnancy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv Ther. 2020;37:27-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Regenstein A. Risk of warfarin during pregnancy with mechanical valve prostheses. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:1040-1041. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Reducing the risk of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy and the puerperium (Green Top Guideline No.37a). London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2015. Available from: https://www.Rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/gtg-37a.pdf. |

| 18. | van Hagen IM, Roos-Hesselink JW, Ruys TP, Merz WM, Goland S, Gabriel H, Lelonek M, Trojnarska O, Al Mahmeed WA, Balint HO, Ashour Z, Baumgartner H, Boersma E, Johnson MR, Hall R; ROPAC Investigators and the EURObservational Research Programme (EORP) Team*. Pregnancy in Women With a Mechanical Heart Valve: Data of the European Society of Cardiology Registry of Pregnancy and Cardiac Disease (ROPAC). Circulation. 2015;132:132-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tooher R, Gates S, Dowswell T, Davis LJ. Prophylaxis for venous thromboembolic disease in pregnancy and the early postnatal period. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;CD001689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |