Published online Feb 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i4.757

Peer-review started: October 18, 2019

First decision: November 11, 2019

Revised: November 15, 2019

Accepted: January 15, 2020

Article in press: January 15, 2020

Published online: February 26, 2020

Processing time: 131 Days and 11.9 Hours

Previous studies found several factors associated with suicide in schizophrenic patients, such as age, sex, education level, history of suicide attempts, psychotic symptoms, social factors, and substance abuse. However, there might be some additional factors that were not considered in previous studies but may be correlated with a greater likelihood of suicide attempts, such as medication and treatment.

To investigate the prevalence of suicide attempts and identify the risk of suicidality in hospitalized schizophrenia patients.

This is a cross-sectional study of schizophrenic patients admitted to a psychiatric hospital who were 18 years of age or more. The outcomes and possible suicide risk factors in these patients were collated. The current suicide risk was evaluated using the mini-international neuropsychiatric interview module for suicidality and categorized as none (0 points), mild (1-8 points), moderate (9-16 points), or severe (17 or more points). This study used ordinal logistic regression to assess the association of potential risk factors with the current suicide risk in schizophrenic patients.

Of 228 hospitalized schizophrenia patients, 214 (93.9%) were included in this study. The majority (79.0%) of patients were males. Females appeared to have a slightly higher suicidality risk than males, with borderline significance. With regard to the current suicide risk assessed with the mini-international neuropsychiatric interview, 172 (80.4%) schizophrenic patients scored zero, 20 (9.4%) had a mild risk, 8 (3.7%) had a moderate risk, and 14 (6.5%) had a severe risk. The total prevalence of current suicide risk in these schizophrenic patients was 19.6%. Based on multivariable ordinal logistic regression analysis with backward elimination, it was found that younger age, a current major depressive episode, receiving fluoxetine or lithium carbonate in the previous month, or a relatively higher Charlson comorbidity index score were all significantly and independently associated with a higher level of suicide risk.

The prevalence rate of suicide attempts in schizophrenia is high. Considering risk factors in routine clinical assessments, environmental manipulations and adequate treatment might prevent or decrease suicide in these patients.

Core tip: The results of the present study suggest that the prevalence of suicidality in schizophrenic patients is high (19.6%). Females appear to have a slightly higher suicide risk than males, with borderline significance. Additionally, the factors related to higher levels of suicide risk were younger age, a current major depressive episode, receiving fluoxetine or lithium carbonate in the previous month, and a relatively higher score on the Charlson comorbidity index. Based on such findings, routine identification of suicidality, including suicidal ideation, suicide plans, suicide attempts, and monitoring and reducing the related factors should be beneficial in the management of inpatient schizophrenic patients.

- Citation: Woottiluk P, Maneeton B, Jaiyen N, Khemawichanurat W, Kawilapat S, Maneeton N. Prevalence and associated factors of suicide among hospitalized schizophrenic patients. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(4): 757-770

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i4/757.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i4.757

Suicide is common in schizophrenic patients. Previous studies have shown that the life-time risk of suicide in these patients is approximately 5%[1]. One survey found that 51.2% of hospitalized schizophrenia patients reported clear suicidal ideation[2], and this may predict later suicide attempts in females[3]. Additionally, a prior study illustrated that 23% (43/187) of hospitalized patients had a history of attempted suicide, and 15% of hospitalized patients (28/187) and 65% of attempters (28/43) attempted suicide during hospitalization[4]. Suicide in schizophrenic patients is associated with several factors. A previous systematic review summarized the risk factors for suicide in schizophrenic patients as young age, male sex, a high level of education, previous suicide attempts, depressive symptoms, active hallucinations and delusions, presence of insight, family history of suicide and substance abuse[1]. In the early phase of schizophrenia, the risk factors for suicide include previous suicide attempts, adverse social factors, psychotic symptoms, and substance abuse[5]. Comorbid medical illness[6] is also a substantial issue in schizophrenic patients. It has been estimated that three-quarters of patients with schizophrenia have another medical diagnosis. The number of medical problems is correlated not only with perceived physical health, but also with the severity of psychotic and depressive symptoms and a greater likelihood of a history of suicide attempt[7].

The study of risk factors for suicide in hospitalized schizophrenia has been especially limited in Asian populations. Worldwide, studies have tended to include small samples or multisite samples with fewer than 50 suicidal patients per site. Consequently, we aimed to investigate the prevalence of and risk factors for suicide in hospitalized schizophrenic patients.

A cross-sectional study was conducted from January to November 2014 at Suan Prung Psychiatric Hospital, Thailand. The research setting is a 700-bed hospital under the supervision of the Department of Mental Health, Ministry of Public Health. It is the largest psychiatric hospital in the northern part of Thailand, which serves the community with nearly 60000 outpatient visits annually and 700 psychiatric inpatients daily. The region includes thirteen provinces with a population of nearly ten million people. This pilot study included all stable hospitalized patients with all types of schizophrenia who were aged 18-60 years; fulfilled the inclusion criteria for their diagnosis based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision; received any treatment (oral or injected antipsychotic drugs, electroconvulsive therapy, and psychosocial intervention, etc.); and could verbally communicate. In the case of uneducated patients, we collected the data by interviewing them and gathered additional details from their relatives. The exclusion criteria included unstable medical conditions, impaired consciousness, significant hearing impairment, any degree of visual impairment, or the lack of the communication skills necessary to ensure the reliability of the test scores. Patients who did not give informed consent, had other psychotic disorders (schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, delusional disorder, dementia, etc.), or who were discharged before being evaluated for the risk of suicide were also excluded from the study. The researcher provided details about the assessment procedure to eligible patients. The diagnosis for those patients was also confirmed using the mini-international neuropsychiatric interview (MINI), Thai Version 5.0.0[8].

Demographic data: The baseline demographic data included sex, age, educational level, marital status, occupation, personal and household income, and debt. Mental illness was screened using the MINI, Thai version 5.0.0, which is administered in a short structured diagnostic interview[8]. We collected the type and duration of illness, medical treatment, use of electroconvulsive therapy, use of psychotherapy, use of family therapy, and other treatments from the medical records.

Treatment satisfaction: Likert scales have become the most popular scale for measuring public opinion on any issue[9,10]. While they offer the advantage of measuring the degree or strength of an opinion, items scored on a Likert scale are still subject to important and pervasive measurement liability due to the “agreement response set,” which is the tendency for survey respondents to agree with any statement to appear positive or agreeable. The study adopted a 10-item Likert-type scale, similar to other studies[9,10].

Comorbid physical illness: To determine the severity of physical illness, the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was evaluated in all patients who were enrolled in the study[11]. Medical conditions included in the Charlson Index were considered as a measure of comorbidity. This assessment tool predicts the one-year mortality for a patient who has a certain number of comorbid conditions. Each condition is assigned a score of 1, 2, 3, or 6, depending on the associated risk of dying. We summed the scores to provide a total score to predict mortality. The clinical conditions and associated scores are as follows: 1 point was assigned for cerebrovascular disease, chronic pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, connective tissue disease, dementia, myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, peptic ulcer, uncomplicated diabetes mellitus and chronic liver disease; 2 points were assigned for hemiplegia, leukemia, lymphoma, diabetes with end-stage organ damage, moderate or severe kidney disease, and nonmetastatic malignant solid tumor; and 3 points were assigned for moderate or severe liver disease. Patients received a score of 6 if they had a malignant solid tumor or AIDS.

Suicide risk: The suicide risk was evaluated using the suicidality module of the MINI, Thai version 5.0.0, which is administered in a short structured diagnostic interview[8]. The suicidality module consists of eight items designed to evaluate the risk of suicide via a number of questions divided into two aspects (in the past one month and in one’s lifetime). The seven items designated for the evaluation of suicide risk in the preceding month were as follows: Q1: Have you thought that you would be better off dead or wished you were dead? (yes = 1, no = 0); Q2: Have you wanted to harm yourself? (yes = 2, no = 0); Q3: Have you thought about suicide? (yes = 6, no = 0); Q4: Have you had a suicide plan? (yes = 8, no = 0); Q5: Have you had a feasible suicide plan? (yes = 9, no = 0); Q6: Did you ever self-harm? (yes = 4, no = 0); and Q7: Did you make a suicide attempt? (yes = 10, no = 0). Only one item evaluates the lifetime suicide risk; Q8: Have you ever made a suicide attempt? The suicidal ideation, planning, and attempts in the previous month and the history of lifetime suicidal attempt are evaluated based on these items. The individual scores are summed, and the total score is categorized as no risk (0 points), low risk (1-8 points), medium risk (9-16 points), and high risk (17 or more points)[12]. The prevalence of suicidality was reported.

Psychosocial scores and the accessibility of weapons and toxic chemicals scores: The psychosocial aspects were the patient’s perception of what was happening in their life. These aspects were risk factors for suicide in schizophrenia, such as the relationships between patients and others, having been reprimanded or blamed in public, being criticized by others and housing and community environment[13,14]. The researcher ranked each question from 1 to 5 (the summed total score ranged from 8-40), with a higher psychosocial score potentially increasing psychosocial stress experienced by patients. Moreover, the study also evaluated the accessibility of weapons and toxic chemicals. Each question was scored from 1 to 5, with a higher score indicating a higher risk of accessing weapons or toxic chemicals. The third quartile was considered the cut-off for the categorization of both the psychosocial scores and the accessibility of weapons and toxic chemicals scores.

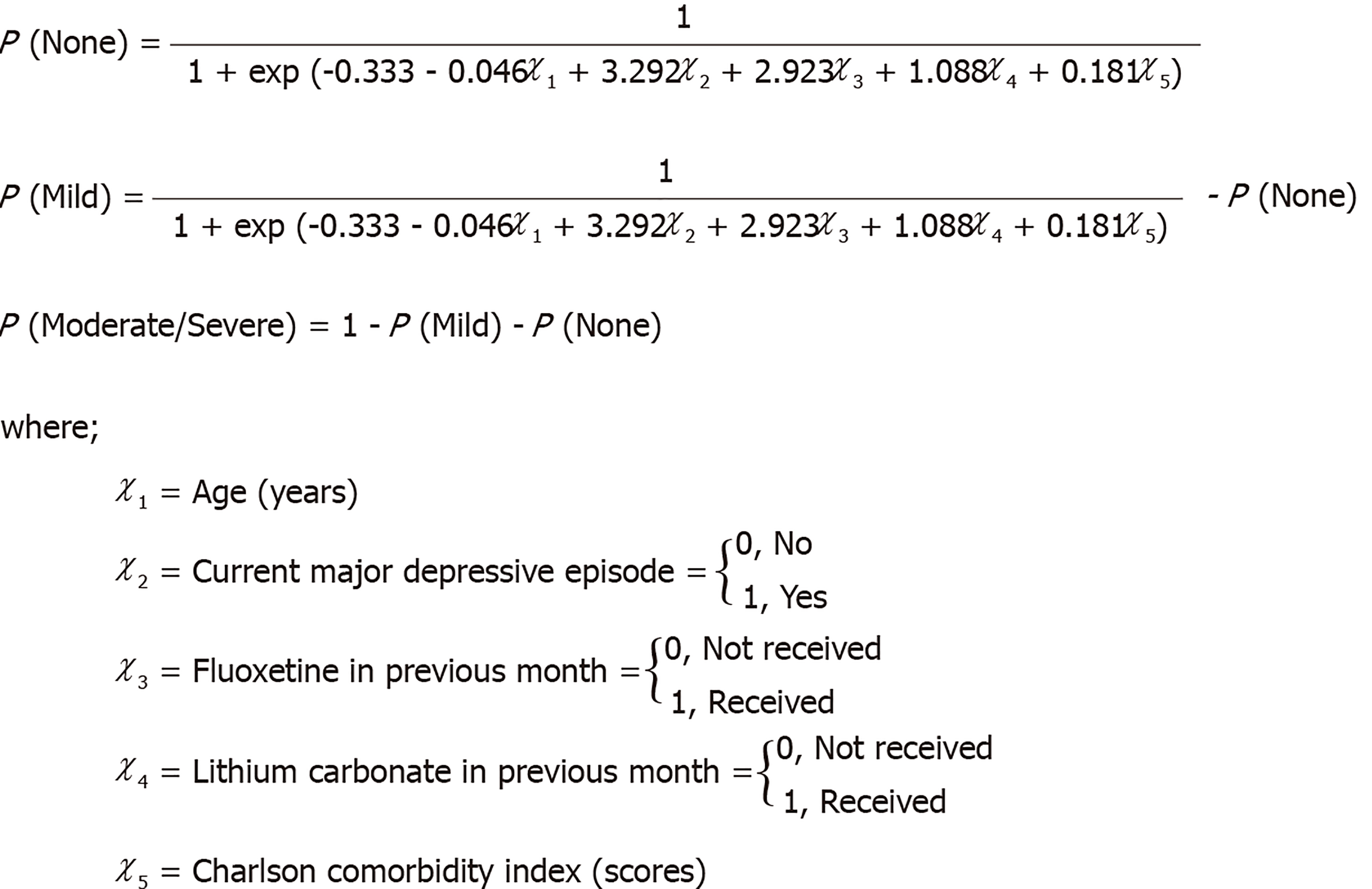

The study estimated and compared the prevalence of suicide risk between male and female patients using Fisher’s exact test. The distribution of current suicide risk was described as frequencies and percentages for each level. We described and compared the characteristics at enrollment (baseline), including sociodemographic data, medication in the previous month, history of treatment, comorbid physical illnesses, the psychosocial scores and the accessibility of weapons and toxic chemicals scores. We present the data as medians and interquartile ranges for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. We used the Kruskal-Wallis test and Fisher’s exact test to determine the difference between patients in each suicidal risk level with regard to the continuous and categorical variables, respectively. We described the data and explained the association of potential risk factors using ordinal logistic regression based on the Wald test[15,16]. The variables with P < 0.25 in univariable analysis were included in the multivariable analysis with backward elimination[17]. The proportional odds assumption and possible interactions for each factor with the suicide risk were determined in the final model. We provide the equations used to predict the probabilities of each level of suicide risk based on the coefficients of thresholds and risk factors in the final model below. All analyses were performed using Stata version 15 (StataCorp LLC, Texas, United States). The statistical methods in this study were reviewed by Assoc. Prof. Dr. Patrinee Traisathit from the Department of Statistics, Faculty of Science, Chiang Mai University.

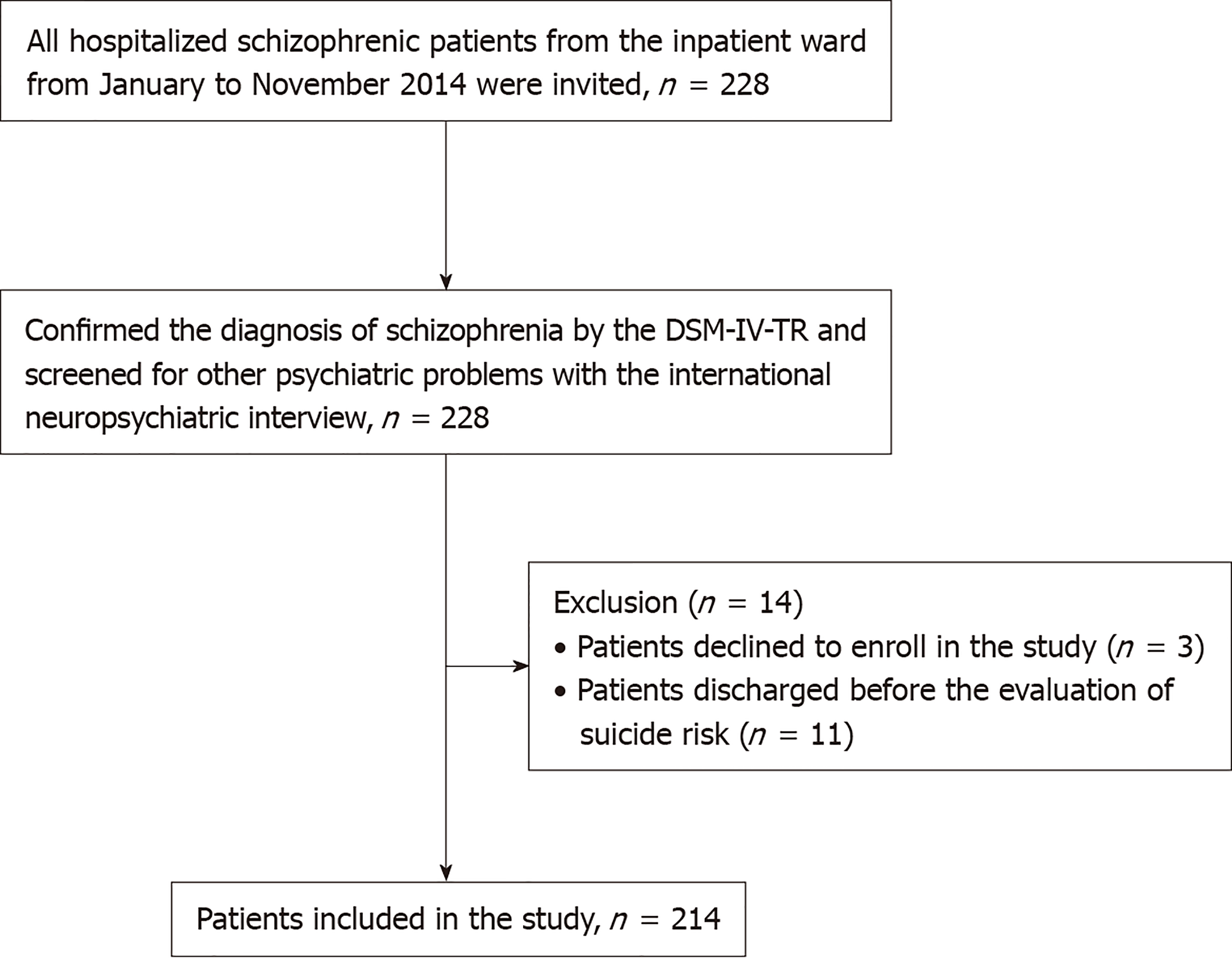

We approached two hundred twenty-eight schizophrenic patients in the inpatient ward from January to November 2014, and 214 (93.9%) patients were included and analyzed in this study. We excluded 14 patients (6.1%) due to refusal to enroll in the study, discharge before suicide risk evaluation, or incomplete or duplicate data (Figure 1).

Table 1 illustrates the descriptive and comparative baseline characteristics of the patients. The majority (79.0%) of the patients were males. Females appeared to have a slightly higher suicidality risk than males, with borderline significance. The median age (range) of these patients was 37.9 (32.2-47.3) years. Most of the participants had completed less than 13 years of education (92.1%), had no spouse (85.1%), were unemployed (37.8%), or had a low occupational status, such as agriculturist (15.0%), and laborer (37.8%). Owing to unemployment or employment in poorly paid fields, the patients had low incomes, and nearly one-third of them had debt. Work status (employed or unemployed) was not associated with different levels of suicide risk. The mean (range) duration of schizophrenia was 3.79 (0.04-10.39) years, and most of the patients were paranoid.

| Characteristics | Total (n = 214) | No risk (n = 172) | Low risk (n = 20) | Moderate/Severe risk (n = 22) | P value |

| Sociodemographic | |||||

| Sex | 0.059 | ||||

| Male | 169 (79.0) | 139 (82.2) | 17 (10.1) | 13 (7.7) | |

| Female | 45 (21.0) | 33 (73.3) | 3 (6.7) | 9 (20.0) | |

| Age (yr) (n = 213) | 37.9 (32.2-47.3) | 38.9 (33.4-47.4) | 33.5 (31.2-47.8) | 32.9 (22.7-43.7) | 0.051 |

| Educational level | 0.962 | ||||

| Uneducated | 18 (8.4) | 16 (88.8) | 1 (5.6) | 1 (5.6) | |

| 1-6 yr | 93 (43.5) | 74 (79.6) | 10 (10.7) | 9 (9.7) | |

| 7-9 yr | 53 (24.8) | 43 (81.1) | 4 (7.6) | 6 (11.3) | |

| 10-12 yr | 33 (15.4) | 24 (72.7) | 4 (12.1) | 5 (15.2) | |

| 13 yr or more | 17 (7.9) | 15 (88.2) | 1 (5.9) | 1 (5.9) | |

| Marital status | 0.433 | ||||

| Single | 145 (67.8) | 117 (80.7) | 15 (10.3) | 13 (9.0) | |

| Married | 32 (14.9) | 28 (87.5) | 1 (3.1) | 3 (9.40) | |

| Divorced/Separated | 31 (14.5) | 22 (71.0) | 3 (9.7) | 6 (19.3) | |

| Widowed | 6 (2.8) | 5 (83.3) | 1 (16.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Occupation | 0.396 | ||||

| Unemployed | 81 (37.8) | 61 (75.3) | 9 (11.1) | 11 (13.6) | |

| Laborer | 81 (37.8) | 68 (83.9) | 5 (6.2) | 8 (9.9) | |

| Agriculturist | 32 (15.0) | 27 (84.4) | 3 (9.4) | 2 (6.2) | |

| Entrepreneur | 11 (5.1) | 10 (90.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (9.1) | |

| Government officer | 1 (0.5) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| State enterprise/Private agency | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Student | 1 (0.5) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Priest | 7 (3.3) | 4 (57.1) | 3 (42.9) | 0 (0) | |

| Personal annual income (US dollars1) (n = 204) | 1125 (563-1875) | 1125 (563-1969) | 750 (300-1875) | 1875 (938-1875) | 0.235 |

| Household annual income (US dollars1) (n = 203) | 2438 (1125-3750) | 2250 (1125-3750) | 1875 (938-3750) | 3188 (1875-5625) | 0.263 |

| Debt (n = 204) | 0.132 | ||||

| No | 142 (69.6) | 113 (79.6) | 16 (11.3) | 13 (9.1) | |

| Yes | 62 (30.4) | 52 (83.9) | 2 (3.2) | 8 (12.9) | |

| Mental illness | |||||

| Major depressive episode: Current | < 0.001a | ||||

| No | 205 (95.8) | 171 (83.4) | 19 (9.3) | 15 (7.3) | |

| Yes | 9 (4.2) | 1 (11.1) | 1 (11.1) | 7 (77.8) | |

| ICD10: Schizophrenia type | 0.083 | ||||

| Paranoid | 147 (68.7) | 120 (81.6) | 13 (8.8) | 14 (9.5) | |

| Disorganized | 3 (1.4) | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Catatonic | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100.0) | |

| Undifferentiated | 62 (28.9) | 50 (80.6) | 6 (9.7) | 6 (9.68) | |

| Postschizophrenia depression | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Residual | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Simple schizophrenia | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100.0) | |

| Duration of schizophrenia (yr) (n = 209) | 3.79 (0.04-10.39) | 3.49 (0.04-10.38) | 9.86 (0.04-14.22) | 1.38 (0.02-8.95) | 0.137 |

| Medication in previous month | |||||

| Oral antipsychotic drugs | |||||

| Clozapine | 0.775 | ||||

| Not received | 140 (65.4) | 114 (81.4) | 13 (9.3) | 13 (9.3) | |

| Received | 74 (34.6) | 58 (78.4) | 7 (9.4) | 9 (12.2) | |

| Dose (mg/d) | 100 (50-100) | 100 (50-100) | 100 (50-100) | 100 (50-100) | |

| Risperidone | 0.511 | ||||

| Not received | 179 (83.6) | 145 (81.0) | 15 (8.4) | 19 (10.6) | |

| Received | 35 (16.4) | 27 (77.1) | 5 (14.3) | 3 (8.6) | |

| Dose (mg/d) | 4 (4-6) | 4 (4-6) | 6 (6-6) | 4 (2-6) | |

| Haloperidol | 0.536 | ||||

| Not received | 199 (93.0) | 159 (79.9) | 20 (10.0) | 20 (10.0) | |

| Received | 15 (7.0) | 13 (86.6) | 0 (0) | 2 (13.3) | |

| Dose (mg/d) | 10 (8-10) | 10 (8-10) | 0 (0) | 9 (8-10) | |

| Trifluoperazine | 0.097 | ||||

| Not received | 167 (78.0) | 131 (78.4) | 15 (9.0) | 21 (12.6) | |

| Received | 47 (22.0) | 41 (87.2) | 5 (10.7) | 1 (2.1) | |

| Dose (mg/d) | 20 (15-20) | 20 (15-20) | 20 (20-20) | 20 (20-20) | |

| Perphenazine | 0.518 | ||||

| Not received | 139 (65.0) | 113 (81.3) | 14 (10.1) | 12 (8.6) | |

| Received | 75 (35.0) | 59 (78.7) | 6 (8.0) | 10 (13.3) | |

| Dose (mg/d) | 24 (16-24) | 24 (16-24) | 24 (24-24) | 16 (16-24) | |

| Chlorpromazine | 0.112 | ||||

| Not received | 156 (72.9) | 122 (78.2) | 14 (9.0) | 20 (12.8) | |

| Received | 58 (27.1) | 50 (86.2) | 6 (10.4) | 2 (2.4) | |

| Dose (mg/d) | 50 (50-50) | 50 (50-50) | 50 (50-50) | 50 (50-50) | |

| Long-acting antipsychotic drugs | |||||

| Fluphenazine decanoate | 0.008a | ||||

| Not received | 160 (74.8) | 128 (80.0) | 11 (6.9) | 21 (13.1) | |

| Received | 54 (25.2) | 44 (81.5) | 9 (16.7) | 1 (1.8) | |

| Dose (mg/mo) | 25 (25-25) | 25 (25-25) | 25 (25-25) | 25 (25-25) | |

| Haloperidol decanoate | 0.337 | ||||

| Not received | 198 (92.5) | 160 (80.8) | 17 (8.6) | 21 (10.6) | |

| Received | 16 (7.5) | 12 (75.0) | 3 (18.8) | 1 (6.2) | |

| Dose (mg/mo) | 50 (50-50) | 50 (50-50) | 50 (50-50) | 50 (50-50) | |

| Anxiolytic and hypnotic drugs | |||||

| AMA2 | 0.605 | ||||

| Not received | 199 (93.0) | 158 (79.4) | 20 (10.1) | 21 (10.5) | |

| Received | 15 (7.0) | 14 (93.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (6.7) | |

| Clonazepam | 1.000 | ||||

| Not received | 203 (94.9) | 163 (80.3) | 19 (9.4) | 21 (10.3) | |

| Received | 11 (5.1) | 9 (81.8) | 1 (9.1) | 1 (9.1) | |

| Dose (mg/d) | 2 (2-2) | 2 (2-2) | 2 (2-2) | 2 (2-2) | |

| Lorazepam | 0.161 | ||||

| Not received | 202 (94.4) | 163 (80.7) | 20 (9.9) | 19 (9.4) | |

| Received | 12 (5.6) | 9 (75.0) | 0 (0) | 3 (25.0) | |

| Dose (mg/d) | 2 (1-2) | 2 (1-2) | 0 (0) | 2 (1-2) | |

| Diazepam | 0.931 | ||||

| Not received | 186 (86.9) | 148 (79.6) | 18 (9.7) | 20 (10.7) | |

| Received | 28 (13.1) | 24 (85.7) | 2 (7.1) | 2 (7.1) | |

| Dose (mg/d) | 10 (5-10) | 7.5 (5-10) | 10 (10-10) | 10 (10-10) | |

| Antidepressants | |||||

| Fluoxetine | < 0.001a | ||||

| Not received | 201 (93.9) | 169 (84.1) | 19 (9.4) | 13 (6.5) | |

| Received | 13 (6.1) | 3 (23.1) | 1 (7.7) | 9 (69.2) | |

| Dose (mg/d) | 20 (20-20) | 20 (20-20) | 20 (20-20) | 20 (20-20) | |

| Sertraline | 0.483 | ||||

| Not received | 211 (98.6) | 170 (80.6) | 20 (9.5) | 21 (9.9) | |

| Received | 3 (1.4) | 2 (66.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (33.3) | |

| Dose (mg/d) | 50 (50-50) | 50 (50-50) | 0 (0) | 50 (50-50) | |

| Mianserin | 0.196 | ||||

| Not received | 213 (99.5) | 172 (80.7) | 20 (9.4) | 21 (9.9) | |

| Received | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100.0) | |

| Dose (mg/d) | 30 (30-30) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 30 (30-30) | |

| Other drugs | |||||

| Lithium carbonate | 0.018a | ||||

| Not received | 189 (88.3) | 157 (83.1) | 15 (7.9) | 17 (9.0) | |

| Received | 25 (11.7) | 15 (60.0) | 5 (20.0) | 5 (20.0) | |

| Dose (mg/d) | 600 (600-600) | 600 (600-600) | 600 (600-600) | 600 (600-600) | |

| Valproate | 0.161 | ||||

| Not received | 201 (93.9) | 163 (81.1) | 17 (8.5) | 21 (10.4) | |

| Received | 13 (6.1) | 9 (69.2) | 3 (23.1) | 1 (7.7) | |

| Dose (mg/d) | 600 (400-600) | 600 (400-600) | 600 (600-800) | 600 (600-600) | |

| Trihexyphenidyl HCl | 0.637 | ||||

| Not received | 18 (8.4) | 14 (77.7) | 1 (5.6) | 3 (16.7) | |

| Received | 196 (91.6) | 158 (80.6) | 19 (9.7) | 19 (9.7) | |

| Dose (mg/d) | 4 (4-6) | 4 (4-6) | 4 (4-6) | 4 (4-6) | |

| Level of medication compliance | 0.413 | ||||

| Score less than 5 | 133 (62.2) | 110 (82.7) | 12 (9.0) | 11 (8.3) | |

| Score 5 or more | 81 (37.8) | 62 (76.5) | 8 (9.9) | 11 (13.6) | |

| History of treatment | |||||

| Electroconvulsive therapy | 0.290 | ||||

| No | 150 (70.1) | 124 (82.7) | 11 (7.3) | 15 (10.0) | |

| Yes | 64 (29.9) | 48 (75.0) | 9 (14.1) | 7 (10.9) | |

| Psychotherapy | 0.232 | ||||

| No | 200 (93.5) | 162 (81.0) | 17 (8.5) | 21 (10.5) | |

| Yes | 14 (6.5) | 10 (71.5) | 3 (21.4) | 1 (7.1) | |

| Family therapy | NA | ||||

| No | 214 (100.0) | 172 (80.4) | 20 (9.3) | 22 (10.3) | |

| Yes | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Other treatment | 1.000 | ||||

| No | 205 (95.8) | 164 (80.0) | 20 (9.8) | 21 (10.2) | |

| Yes | 9 (4.2) | 8 (88.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (11.1) | |

| Treatment satisfaction (n = 212) | 8 (7-10) | 8 (7-10) | 9 (7-10) | 8 (6-10) | 0.379 |

| Other indices | |||||

| Charlson Comorbidity index score (n = 213) | 0.086 | ||||

| None (0 score) | 207 (97.2) | 169 (81.6) | 18 (8.7) | 20 (9.7) | |

| Low (1-2 score) | 4 (1.8) | 2 (50.0) | 1 (25.0) | 1 (25.0) | |

| Moderate (3-4 score) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| High (5 score or more) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0) | |

| Psychosocial score (n = 208) | 21 (18-25) | 21 (18-25) | 19 (18-24) | 20 (18-23) | 0.214 |

| Level of psychosocial score (n = 208) | 0.128 | ||||

| Good (less than 25 score) | 156 (75.0) | 120 (76.9) | 17 (10.9) | 19 (12.2) | |

| Poor (25 score or more) | 52 (25.0) | 47 (90.3) | 2 (3.9) | 3 (5.8) | |

| Weapons and toxic chemicals accessibility score (n = 208) | 18 (9.5-29) | 18 (10-28) | 19 (11-30) | 15 (9-30) | 0.585 |

| Level of weapons and toxic chemicals accessibility score (n = 208) | 0.791 | ||||

| Low (less than 25 score) | 142 (68.3) | 114 (80.2) | 12 (8.5) | 16 (11.3) | |

| High (25 score or more) | 66 (31.7) | 53 (80.3) | 7 (10.6) | 6 (9.1) | |

Of the 214 included patients, 20 (9.3%) and 22 (10.3%) patients were classified in the low and medium to high suicide risk groups, respectively. Based on the MINI, Thai version 5.0.0, 2.3% of patients had schizophrenia with secondary depression. From the assessment, 2.3% and 4.2% reported lifetime and current major depressive episodes, respectively. The oral antipsychotic medications used in schizophrenic patients in the previous month were clozapine, risperidone, haloperidol, trifluoperazine, perphenazine, and chlorpromazine. Moreover, some patients received long-acting antipsychotic drug injections, such as fluphenazine decanoate or haloperidol decanoate, to control their psychotic symptoms. Table 1 shows the additional medications and psychosocial interventions used. Combined with other treatments, nearly one-third of patients also received electroconvulsive therapy. The overall treatment satisfaction score was 8 (7-10), indicating that patients were satisfied with their treatment. The median treatment satisfaction level was not different between suicide risk levels. The results of the CCI indicated that 2.8% of the cases had a physical disease such as cerebrovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, peripheral vascular disease, and peptic ulcer. Table 1 also shows the psychosocial scores and the accessibility of weapons and toxic chemicals scores. Surprisingly, the group of patients who had higher weapons and toxic chemicals accessibility scores did not have higher suicide risk levels than the group of patients who had low scores.

The lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts in schizophrenic patients was 15.6%, and it was not different between males and females (13.7% vs 22.7%, P = 0.162). The current prevalence of suicidality in schizophrenic patients was 19.6%, and it was classified as mild, moderate, or severe (9.4%, 3.7% and 6.5%, respectively). Because there were few observations in some categories, we condensed the patients with moderate risk and severe risk of suicide into the same category for analysis. All independent variables that had statistical significance at the bivariate level (P < 0.250) were eligible and included in the analysis.

Based on the univariable ordinal logistic regression analyses (Table 2), the selected independent variables that had statistical significance at the bivariate level (P < 0.250) were eligible and included in the multivariable analysis to determine their associations with suicide risk in schizophrenic patients. The independent variables were sex; age; current major depressive episode; use of psychotropic medications such as chlorpromazine, trifluoperazine, AMA (Amobarbital 50 mg and chlorpromazine HCl 25 mg), fluoxetine, and lithium carbonate; use of electroconvulsive therapy; level of medication compliance; CCI score; and the psychosocial score. The results of multivariable ordinal logistic regression analysis with backward elimination showed that a younger age, a current major depressive episode, the use of fluoxetine or lithium carbonate in the previous month, or a relatively higher CCI score were significantly independently associated with a higher level of suicide risk (Table 3).

| Characteristics | Univariable ordinal logistic regression | ||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | ||

| Sociodemographic | |||

| Sex | 0.116 | ||

| Male | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 1.85 (0.86-3.98) | ||

| Age (yr) | 0.96 (0.93-0.99) | 0.026a | |

| Educational level | 0.609 | ||

| Uneducated | 1.00 | ||

| 1-6 yr | 2.03 (0.43-9.56) | ||

| 7-9 yr | 1.90 (0.38-9.57) | ||

| 10-12 yr | 3.01 (0.58-15.70) | ||

| 13 yr or more | 1.07 (0.13-8.53) | ||

| Marital status | 0.316 | ||

| Single | 1.00 | ||

| Married | 0.63 (0.20-1.93) | ||

| Divorced/Separated/Widowed | 1.60 (0.70-3.66) | ||

| Occupation | 0.272 | ||

| Unemployed | 1.00 | ||

| Employed | 0.60 (0.28-1.30) | ||

| Other | 0.29 (0.04-2.42) | ||

| Personal annual income (US dollars1) | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.918 | |

| Household annual income (US dollars1) | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.881 | |

| Debt | 0.598 | ||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 0.81 (0.37-1.78) | ||

| Mental illness | |||

| Major depressive episode: Current | < 0.001a | ||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 43.62 (8.51-223.65) | ||

| ICD10: schizophrenia type | 0.638 | ||

| Paranoid | 1.00 | ||

| Other | 1.19 (0.58-2.44) | ||

| Duration of schizophrenia (years) | 1.00 (0.96-1.05) | 0.877 | |

| Medication in previous month | |||

| Clozapine | 0.565 | ||

| Not received | 1.00 | ||

| Received | 1.23 (0.61-2.45) | ||

| Risperidone | 0.683 | ||

| Not received | 1.00 | ||

| Received | 1.20 (0.51-2.84) | ||

| Fluphenazine | 0.583 | ||

| Not received | 1.00 | ||

| Received | 0.80 (0.37-1.75) | ||

| Chlorpromazine | 0.151 | ||

| Not received | 1.00 | ||

| Received | 0.54 (0.24-1.25) | ||

| Haloperidol | 0.603 | ||

| Not received | 1.00 | ||

| Received | 0.67 (0.14-3.08) | ||

| Haloperidol decanoate | 0.685 | ||

| Not received | 1.00 | ||

| Received | 1.27 (0.40-4.08) | ||

| Trifluoperazine | 0.143 | ||

| Not received | 1.00 | ||

| Received | 0.50 (0.20-1.27) | ||

| Perphenazine | 0.565 | ||

| Not received | 1.00 | ||

| Received | 1.23 (0.61-2.45) | ||

| AMA2 | 0.234 | ||

| Not received | 1.00 | ||

| Received | 0.29 (0.04-2.25) | ||

| Clonazepam | 0.897 | ||

| Not received | 1.00 | ||

| Received | 0.90 (0.19-4.30) | ||

| Lorazepam | 0.47 | ||

| Not received | 1.00 | ||

| Received | 1.65 (0.42-6.45) | ||

| Diazepam | 0.445 | ||

| Not received | 1.00 | ||

| Received | 0.65 (0.21-1.97) | ||

| Fluoxetine | < 0.001a | ||

| Not received | 1.00 | ||

| Received | 26.77 (7.53-95.20) | ||

| Sertraline | 0.443 | ||

| Not received | 1.00 | ||

| Received | 2.62 (0.22-30.46) | ||

| Lithium carbonate | 0.01a | ||

| Not received | 1.00 | ||

| Received | 3.09 (1.31-7.29) | ||

| Depakine | 0.4 | ||

| Not received | 1.00 | ||

| Received | 1.67 (0.51-5.51) | ||

| Artane | 0.685 | ||

| Not received | 1.00 | ||

| Received | 0.79 (0.25-2.52) | ||

| Score for medication compliance | 0.244 | ||

| Less than 5 | 1.00 | ||

| 5 or more | 1.50 (0.76-2.95) | ||

| History of treatment | |||

| Electroconvulsive therapy | 0.242 | ||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.52 (0.75-3.06) | ||

| Psychotherapy | 0.492 | ||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.51 (0.46-4.94) | ||

| Other treatment | 0.66 | ||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 0.62 (0.07-5.21) | ||

| Treatment satisfaction (score) | 0.99 (0.83-1.18) | 0.911 | |

| Other indices | |||

| Charlson Comorbidity index (score) | 1.10 (0.95-1.26) | 0.195 | |

| Psychosocial score (score) | 0.93 (0.86-1.00) | 0.046a | |

| Weapons and toxic chemicals accessibility score (score) | 0.98 (0.95-1.02) | 0.438 | |

| Characteristics | Multivariable ordinal logistic regression1 | ||

| aOR (95%CI) | P value | Pseudo R2 | |

| Age (per 1 yr increase) | 0.95 (0.92-0.99) | 0.031a | 0.2084 |

| Current major depressive episode | 26.88 (4.05-178.59) | 0.001a | |

| Received fluoxetine in previous month | 18.59 (4.50-76.77) | < 0.001a | |

| Received lithium carbonate in previous month | 2.97 (1.10-8.01) | 0.032a | |

| Charlson comorbidity index (per 1 point increase) | 1.20 (1.03-1.40) | 0.020a | |

The global Wald test for the final model consisted of all risk factors and indicated that the final model did not violate the proportional odds assumption (P = 0.656). There was no interaction between factors in the final model. The equations predicted the probability of each level of suicide risk (Figure 2).

In this hospital-based sample population who received a diagnosis of schizophrenia from a psychiatric hospital, the findings substantiate that the current prevalence of suicidality in schizophrenic patients is 19.6%. The factors associated with the suicide risk in such patients include younger age, a current major depressive episode, the use of fluoxetine or lithium carbonate in the previous month, or a relatively higher CCI score.

In our study, the prevalence of suicide in schizophrenic patients was not different from the findings of previous studies. Previous evidence showed that suicide is common in schizophrenic patients[1,18]. The lifetime prevalence of suicide in these patients is approximately 5%[1,18]. A previous study of rates of suicide in first-admission schizophrenic patients illustrated that 23% of these patients had already attempted suicide, and 15% had attempted suicide necessitating hospitalization[4,5]. According to previous evidence and the results of the present study, effective screening for suicidality in hospitalized schizophrenic patients is necessary as 40%-93% of patients who commit suicide have made a previous suicide attempt[1].

Previous evidence showed that a young age in schizophrenic patients is associated with an elevated incidence of attempted suicide[1]. Another study also indicated that schizophrenic patients with younger age at onset have a high risk of suicide attempt[19], which was consistent with our findings. The higher risk of suicidality in younger schizophrenic patients may be associated with the adverse effects of schizophrenia on many aspects of their lives, including social and occupational functioning. Therefore, psychosocial interventions to improve such functioning, along with medication, may decrease the risk of attempted suicide in these patients.

The association of treatment with lithium or fluoxetine with an increased risk of suicide might be coincidental with treatment need and may not be causative. An underlying mood disorder could be the causative factor, although medication side effects can affect suicidality, especially akathisia.

Schizophrenic patients frequently have poor adherence to antipsychotic medication[20,21]. Additionally, the schizophrenic patients with poor adherence are also significantly more likely to attempt suicide[22]. This was not revealed in our data. Reasons for poor compliance vary in individual patients[23]. Hence, identifying the causes of poor adherence to antipsychotic medications in each patient and improving adherence via multiple approaches may be beneficial[23].

Higher Charlson scores can increase suicidality owing to a higher incidence of depression, greater despair associated with disability, more cognitive impairment and worse coping skills due to severe physical illness.

Because several associated factors increase suicidality in hospitalized schizophrenic patients, the following steps may be beneficial with regard to reducing suicide risk in such patients, especially soon after admission: Providing a safe environment, enhancing patient visibility, providing appropriate patient supervision, conducting a careful clinical evaluation, recognizing the suicide risk, ensuring good teamwork and communication, and administering adequate clinical treatment[24]. If the management of schizophrenic patients with medical illness is complicated, customization in the management model should be considered[25].

There is a lack of evidence supporting the efficacy of first-generation antipsychotics in reducing suicide risk in schizophrenic patients; second-generation antipsychotics, especially clozapine, may be beneficial because they decrease the risk of suicide in such patients[26].

The present study had some limitations. Initially, the sample size was relatively limited compared to multisite studies, but the sample was very large for a single site and compared to other Asian studies. A larger sample size may yield more reliable results.

In conclusion, the results of the present study suggest that the prevalence rate of suicidality in schizophrenic patients is high (19.6%). Females appear to have a slightly higher suicide risk than males, with borderline significance. Additionally, the factors related to higher levels of suicide risk were a younger age, a current major depressive episode, the use of fluoxetine or lithium carbonate in the previous month, and a relatively higher CCI score. Based on such findings, the routine identification of suicidality, including suicidal ideation, suicide plans, and suicide attempts, and monitoring and decreasing the related factors should be beneficial for the management of inpatient schizophrenic patients.

Various factors are related to suicidality in schizophrenia, including age, sex, level of education, past history of suicide attempt, psychotic symptoms, social factors, and substance use disorders.

Although some factors related to suicidality in schizophrenic patients have been identified, additional factors possibly associated with suicide attempts such as medication and treatment in these patients have not been identified. In addition, the influence of culture may modify the risk of suicidality. Hence, the present study may be beneficial for clinicians seeking to identify and monitor the factors related to suicidality in schizophrenic patients.

Our study focused on the prevalence of suicide attempts and investigated the factors associated with suicidality in hospitalized schizophrenic patients.

This cross-sectional study assessed all outcomes and possible suicide risk factors in inpatient schizophrenic patients. The current suicide risk was evaluated using the MINI module for suicidality and categorized as none, mild, moderate, or severe. Ordinal logistic regression was used to assess the associations of potential risk factors with the current suicide risk.

The overall prevalence of suicide risk in the evaluated schizophrenic patients was 19.6%. Our study found that a younger age, a current major depressive episode, the use of fluoxetine or lithium carbonate in the previous month, or a relatively higher Charlson Comorbidity Index score were all significantly and independently associated with a higher level of suicide risk.

The prevalence rate of suicide attempts in hospitalized schizophrenic patients is high. Being young, having a current major depressive episode, receiving fluoxetine or lithium carbonate in the previous month, or having more medical illnesses may increase the risk of suicidality.

Our study suggests that routine clinical assessment, environmental manipulation and adequate treatment might prevent or decrease suicide in hospitalized schizophrenic patients.

We would like to thank all the patients and their families who assisted with the study. We thank all staff members involved in screening, diagnosis, evaluation, data collection, and analyses. We thank the following for his substantial help with this project: Professor Stephen D. Martin, Consultant Psychiatrist to Her Majesty’s Courts and Tribunals Service, United Kingdom. We are grateful for the review of statistical methods in this study provided by Associate Professor Dr. Patrinee Traisathit and the manuscript editing provided by Ms. Ruth Barnard Leatherman.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: Thailand

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Khajehei M, Ugo Fedeli MD S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: Webster JR E-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Hor K, Taylor M. Suicide and schizophrenia: a systematic review of rates and risk factors. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:81-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 648] [Cited by in RCA: 555] [Article Influence: 37.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kim SW, Kim SJ, Mun JW, Bae KY, Kim JM, Kim SY, Yang SJ, Shin IS, Yoon JS. Psychosocial factors contributing to suicidal ideation in hospitalized schizophrenia patients in Korea. Psychiatry Investig. 2010;7:79-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | King CA, Jiang Q, Czyz EK, Kerr DC. Suicidal ideation of psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents has one-year predictive validity for suicide attempts in girls only. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2014;42:467-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cohen S, Lavelle J, Rich CL, Bromet E. Rates and correlates of suicide attempts in first-admission psychotic patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;90:167-171. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Ventriglio A, Gentile A, Bonfitto I, Stella E, Mari M, Steardo L, Bellomo A. Suicide in the Early Stage of Schizophrenia. Front Psychiatry. 2016;7:116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chwastiak LA, Rosenheck RA, McEvoy JP, Keefe RS, Swartz MS, Lieberman JA. Interrelationships of psychiatric symptom severity, medical comorbidity, and functioning in schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:1102-1109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mitchell AJ, Malone D. Physical health and schizophrenia. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2006;19:432-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kittirattanapaiboon P, Khamwongpin, M. The validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). J Ment Health Thailand. 2005;125. |

| 9. | Likert R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arc Psychology. 1932;55. |

| 10. | Robinson J. Likert Scale. In: Michalos AC, editor. Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands 2014; 3620-3362. |

| 11. | Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373-383. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Li H, Luo X, Ke X, Dai Q, Zheng W, Zhang C, Cassidy RM, Soares JC, Zhang X, Ning Y. Major depressive disorder and suicide risk among adult outpatients at several general hospitals in a Chinese Han population. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0186143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Depp CA, Villa J, Schembari BC, Harvey PD, Pinkham A. Social cognition and short-term prediction of suicidal ideation in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2018;270:13-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chang Q, Wu D, Rong H, Wu Z, Tao W, Liu H, Zhou P, Luo G, Xie G, Huang S, Qian C, Yuan Y, Yip PSF, Liu T. Suicide ideation, suicide attempts, their sociodemographic and clinical associates among the elderly Chinese patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. J Affect Disord. 2019;256:611-617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | McCullagh P. Regression Models for Ordinal Data. J Royal Statistical Society Series B (Methodological). 1980;109. |

| 16. | Baker RD, Weinand C, Jeng JC, Hoeksema H, Monstrey S, Pape SA, Spence R, Wilson D. Using ordinal logistic regression to evaluate the performance of laser-Doppler predictions of burn-healing time. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mickey RM, Greenland S. The impact of confounder selection criteria on effect estimation. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:125-137. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Palmer BA, Pankratz VS, Bostwick JM. The lifetime risk of suicide in schizophrenia: a reexamination. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:247-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 698] [Cited by in RCA: 653] [Article Influence: 32.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Uzun O, Tamam L, Ozcüler T, Doruk A, Unal M. Specific characteristics of suicide attempts in patients with schizophrenia in Turkey. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2009;46:189-194. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Valenstein M, Ganoczy D, McCarthy JF, Myra Kim H, Lee TA, Blow FC. Antipsychotic adherence over time among patients receiving treatment for schizophrenia: a retrospective review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1542-1550. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Lacro JP, Dunn LB, Dolder CR, Leckband SG, Jeste DV. Prevalence of and risk factors for medication nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia: a comprehensive review of recent literature. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:892-909. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Bouhlel S, M'solly M, Benhawala S, Jones Y, El-Hechmi Z. [Factors related to suicide attempts in a Tunisian sample of patients with schizophrenia]. Encephale. 2013;39:6-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Haddad PM, Brain C, Scott J. Nonadherence with antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia: challenges and management strategies. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2014;5:43-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 366] [Cited by in RCA: 375] [Article Influence: 34.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sakinofsky I. Preventing suicide among inpatients. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59:131-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ciccone MM, Aquilino A, Cortese F, Scicchitano P, Sassara M, Mola E, Rollo R, Caldarola P, Giorgino F, Pomo V, Bux F. Feasibility and effectiveness of a disease and care management model in the primary health care system for patients with heart failure and diabetes (Project Leonardo). Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2010;6:297-305. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Kasckow J, Felmet K, Zisook S. Managing suicide risk in patients with schizophrenia. CNS Drugs. 2011;25:129-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |