Published online Feb 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i3.600

Peer-review started: November 25, 2019

First decision: December 11, 2019

Revised: December 24, 2019

Accepted: January 8, 2020

Article in press: January 8, 2020

Published online: February 6, 2020

Processing time: 65 Days and 23.3 Hours

Cutaneous epithelioid angiomatous nodules (CEAN) are rare, benign, vascular lesions characterized by benign proliferation of endothelial cells with prominent epithelioid features, which can be easily confused with benign and malignant vascular tumors. However, the etiology of CEAN remains unclear, and no association with infection, trauma, or immunosuppression has been described. This case study indicated that CEAN is closely related to the patient’s impaired immune status and may be induced by cyclosporine.

A 19-year-old boy with nephrotic syndrome (NS) developed large CEAN on the left foot during treatment for NS. He had repeated relapses of edema in the past 6 years and different types of immunosuppressants were administered including methylprednisolone, mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus and cyclosporine; the dosages of these drugs were frequently adjusted. The patient had been receiving cyclosporine and methylprednisolone for 7 mo before he developed CEAN. Cyclosporine was discontinued due to its side effects on skin. After cessation of cyclosporine and 16 mo follow-up, the nodules gradually disappeared without any other treatment for the CEAN.

Impaired immune status is proposed to be a risk factor for CEAN, which may be induced by cyclosporine.

Core tip: As reported in this article, impaired immune status is proposed to be a risk factor for cutaneous epithelioid angiomatous, which may be induced by cyclosporine.

- Citation: Cheng DJ, Zheng XY, Tang SF. Large cutaneous epithelioid angiomatous nodules in a patient with nephrotic syndrome: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(3): 600-605

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i3/600.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i3.600

Cutaneous epithelioid angiomatous nodules (CEAN) are rare, benign, vascular lesions with a well-defined morphologic and immunohistochemical pattern first described by Brenn et al[1] in 2004. Surgical excision and cryotherapy are the treatments of choice for CEAN[1-4]. However, the etiology and pathogenesis of CEAN remain unclear. A recent case report indicated that the patient’s impaired immune status may be a risk factor for CEAN[4]. In all the cases reported to date, few patients with nephrotic syndrome (NS) developed CEAN during immunosuppressive therapy. Here, we report a patient with NS who developed extensive CEAN during treatment with cyclosporine.

A 19-year-old boy had intermittent relapses of NS and leg edema over the past 6 years, and developed rapidly growing large black nodules (Figure 1A) on the left foot with pain and limited activity for 7 d. He also had a cough with a large quantity of dilute white phlegm and shortness of breath after strenuous activity, but no chest pain, fever, diarrhea, headache or abdominal pain. His urine output was approximately 1500 mL in 24 h.

Physical examination showed pain and limited activity of the left leg and edema of both lower extremities.

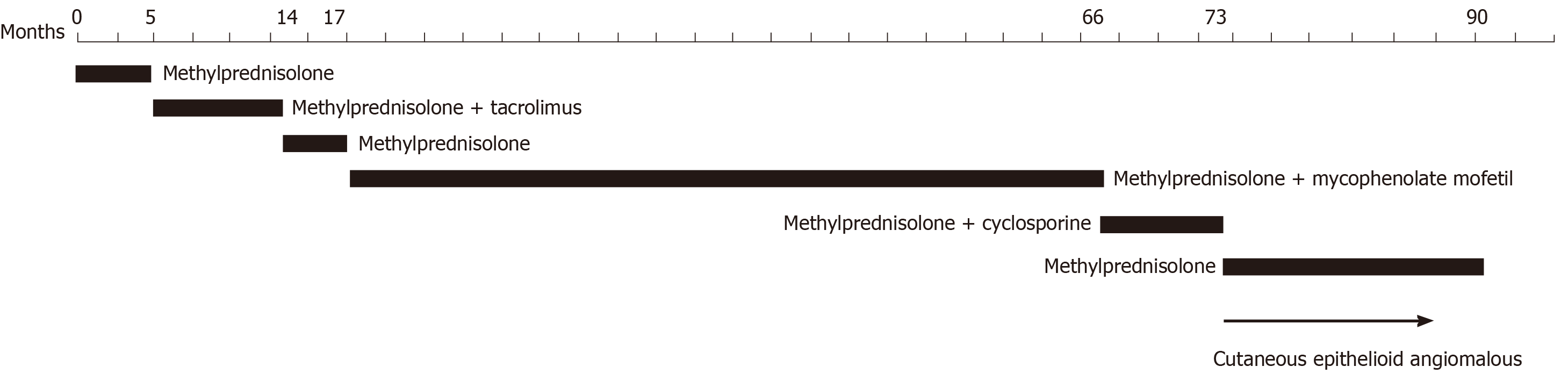

He had a history of secondary hypertension treated with valsartan and NS with long-term administration of immunosuppressants due to repeated recurrences during the past 6 years. Kidney biopsy demonstrated diffuse mild mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis with a small amount of IgA deposition in October 2012. During the recurrences of NS, methylprednisolone, mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus, and cyclosporine (Figure 2) were administered. Before hospitalization, the patient had been receiving methylprednisolone tablets and cyclosporine capsules for 7 mo and valsartan for 6 years. Cyclosporine was discontinued during hospitalization due to its side effects on skin and valsartan was also discontinued.

None.

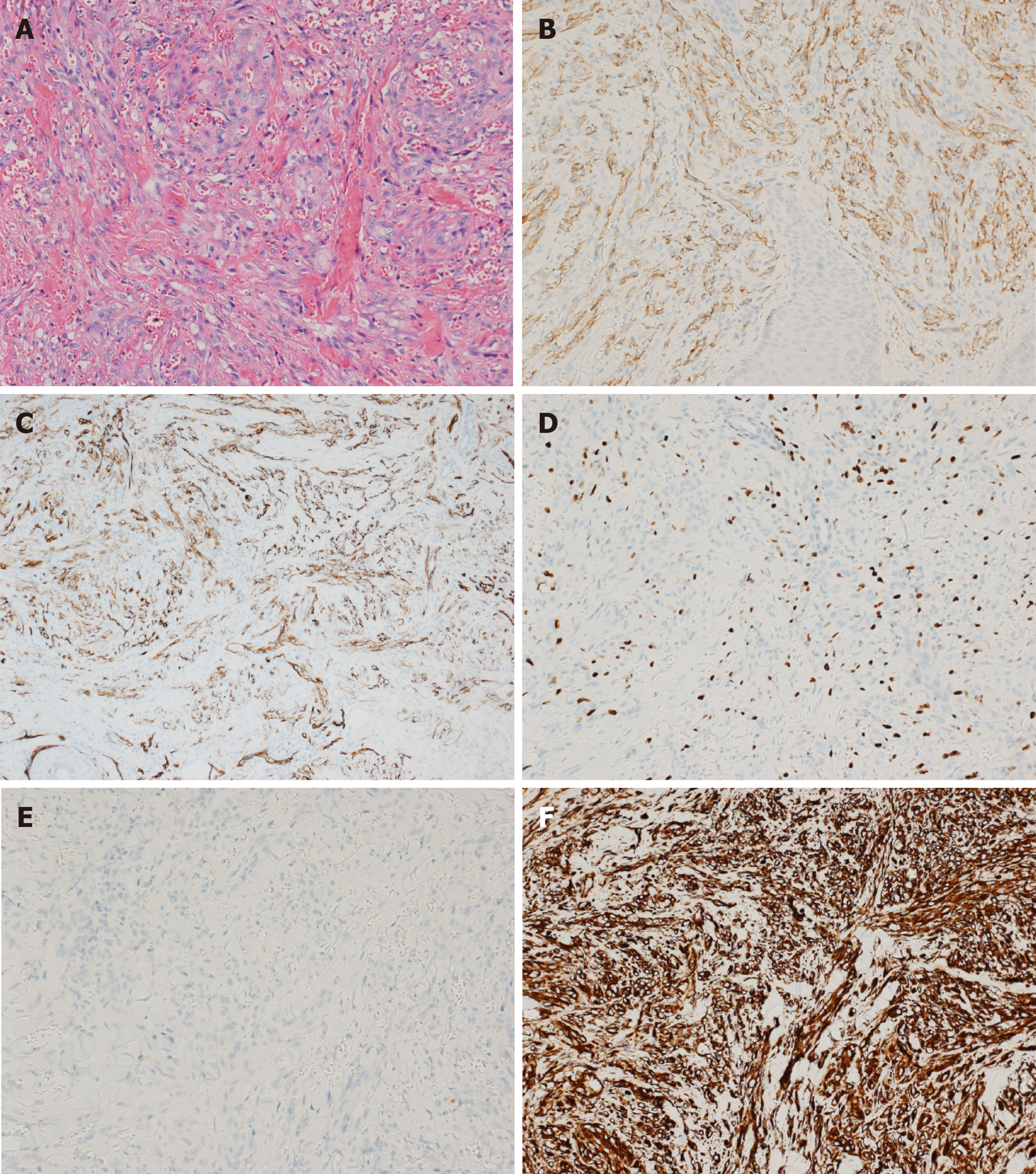

The results of Doppler ultrasonography of the lower extremity and echocardiography were normal. Histopathology of the skin biopsy (Figure 3A) showed numerous nodules in the superficial dermis of the skin composed of epithelioid vascular endothelial cells with mitotic activity and without nuclear atypia. Small vascular channels had formed within the nodules surrounded by collagen. Immunohistochemistry showed that the vascular markers cluster of differentiation 31 (Figure 3B), cluster of differentiation 34 (Figure 3C), and Ki-67 (Figure 3D) were positive, but cytokeratin (Figure 3E) and vimentin (Figure 3F) were negative.

CEAN was diagnosed by clinical features and pathology.

Cyclosporine was discontinued and no other treatments for CEAN were given as family members refused surgical excision.

During 18 d in the hospital, the lesions became slightly smaller after cessation of cyclosporine. The patient’s family opted for conservative therapy and no further treatments for CEAN during the 16 mo follow-up period were administered, although the doctor did recommend further treatments. Fortunately, the lesions gradually disappeared after approximately 16 mo follow-up without any treatment (Figure 1B, C). The patient is currently receiving methylprednisolone and atorvastatin at a dose of 8 mg and 10 mg, respectively, and the results of urinary protein have been negative for several months.

CEAN is a novel clinicopathological entity characterized by benign proliferation of endothelial cells with prominent epithelioid features, which should be distinguished from bacillary angiomatosis, epithelioid hemangioma, epithelioid heman-gioendothelioma, and epithelioid angiosarcoma. The lesions are predominantly located on the trunk, but can also involve the extremities, face and nasal mucosa[1]. Surgical excision and cryotherapy are the treatments of choice for CEAN[1-4], but some patients develop recurrent lesions after complete excision[4]. In the present case, the lesions slowly disappeared after the cessation of cyclosporine, which indicated that CEAN may have been induced by cyclosporine.

Considering the development of this condition, it is likely that CEAN was caused by cyclosporine. A number of studies have reported the side effects of cyclosporine, which can induce hyperlipidemia, hyperuricemia, gingival hyperplasia, hirsutism, convulsions, peptic ulcers, pancreatitis, potassium retention, arterial hypertension, kidney and liver dysfunction[5,6]. Cyclosporine is listed as an International Agency for Research on Cancer Group One carcinogen, and causes squamous cell carcinoma, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and cancer at multiple other sites[7]. One case report described eruptive basal cell carcinoma and keratoacanthoma within 3 mo of initiation of cyclosporine[8], and disease development was similar to that in our case. Immunosuppression- or transplantation-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma occurs in organ-transplant recipients and patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy and tends to disappear with reduction of immunosuppression[9], which indicate that CEAN might also be induced by compromised immunity. However, CEAN induced by cyclosporine has not been previously reported; thus, attention should be paid to the development of skin side effects during treatment with cyclosporine. Only one case report[4] indicated that CEAN was associated with immunosuppression and the patient’s impaired immune status, but no specific medication was mentioned. Taken together, these findings suggest that the patient’s impaired immune status in this report could be a risk factor for CEAN and cyclosporine may induce CEAN.

Impaired immune status may be a risk factor for CEAN, which might be induced by cyclosporine. The immune status of patients should be monitored during long-term immunosuppressive therapy.

We would like to thank the pathologist Rui-De Hu from the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University who provided advice on pathological diagnosis.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gonzalez FM S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Brenn T, Fletcher CD. Cutaneous epithelioid angiomatous nodule: a distinct lesion in the morphologic spectrum of epithelioid vascular tumors. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:14-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Dastgheib L, Aslani FS, Sepaskhah M, Saki N, Motevalli D. A young woman with multiple cutaneous epithelioid angiomatous nodules (CEAN) on her forearm: a case report and follow-up of therapeutic intervention. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:1. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Wong WK, Lim DH, Ong CW. Epithelioid angiomatous nodule of the nasal cavity: Report of 2 cases. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2015;42:341-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chetty R, Kamil ZS, Wang A, Al Habeeb A, Ghazarian D. Cutaneous epithelioid angiomatous nodule: a report of a series including a case with moderate cytologic atypia and immunosuppression. Diagn Pathol. 2018;13:50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Naesens M, Kuypers DR, Sarwal M. Calcineurin inhibitor nephrotoxicity. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:481-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 950] [Cited by in RCA: 1076] [Article Influence: 67.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hošková L, Málek I, Kopkan L, Kautzner J. Pathophysiological mechanisms of calcineurin inhibitor-induced nephrotoxicity and arterial hypertension. Physiol Res. 2017;66:167-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, No. 100A. Pharmaceuticals. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risk to Humans. Lyon (FR): International Agency for Research on cancer; 2012. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK304334/. |

| 8. | Lain EL, Markus RF. Early and explosive development of nodular basal cell carcinoma and multiple keratoacanthomas in psoriasis patients treated with cyclosporine. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:680-682. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Rubinger D, Friedlaender MM, Backenroth R, Eid A, Tochner Z. Kaposi's sarcoma after renal transplantation--withdrawal of immunosuppression or local irradiation? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14:1343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |