Published online Dec 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i24.6330

Peer-review started: June 26, 2020

First decision: September 24, 2020

Revised: October 1, 2020

Accepted: November 4, 2020

Article in press: November 4, 2020

Published online: December 26, 2020

Processing time: 173 Days and 4.5 Hours

The renal system has a specific pleural effusion associated with it in the form of “urothorax”, a condition where obstructive uropathy or occlusion of the lymphatic ducts leads to extravasated fluids (urine or lymph) crossing the diaphragm via innate perforations or lymphatic channels. As a rare disorder that may cause pleural effusion, renal lymphangiectasia is a congenital or acquired abnormality of the lymphatic system of the kidneys. As vaguely mentioned in a report from the American Journal of Kidney Diseases, this disorder can be caused by extrinsic compression of the kidney secondary to hemorrhage.

A 54-year-old man with biopsy-proven acute tubulointerstitial nephropathy experienced bleeding 3 d post hoc, which, upon clinical detection, manifested as a massive perirenal hematoma on computed tomography (CT) scan without concurrent pleural effusion. His situation was eventually stabilized by expeditious management, including selective renal arterial embolization. Despite good hemodialysis adequacy and stringent volume control, a CT scan 1 mo later found further enlargement of the perirenal hematoma with heterogeneous hypodense fluid, left side pleural effusion and a small amount of ascites. These fluid collections showed a CT density of 3 Hounsfield units, and drained fluid of the pleural effusion revealed a dubiously light-colored transudate with lymphocytic predominance (> 80%). Similar results were found 3 mo later, during which time the patient was free of pulmonary infection, cardiac dysfunction and overt hypoalbuminemia. After careful consideration and exclusion of other possible causative etiologies, we believed that the pleural effusion was due to the occlusion of renal lymphatic ducts by the compression of kidney parenchyma and, in the absence of typical dilation of the related ducts, considered our case as extrarenal lymphangiectasia in a broad sense.

As such, our case highlighted a morbific passage between the kidney and thorax under an extraordinarily rare condition. Given the paucity of pertinent knowledge, it may further broaden our understanding of this rare disorder.

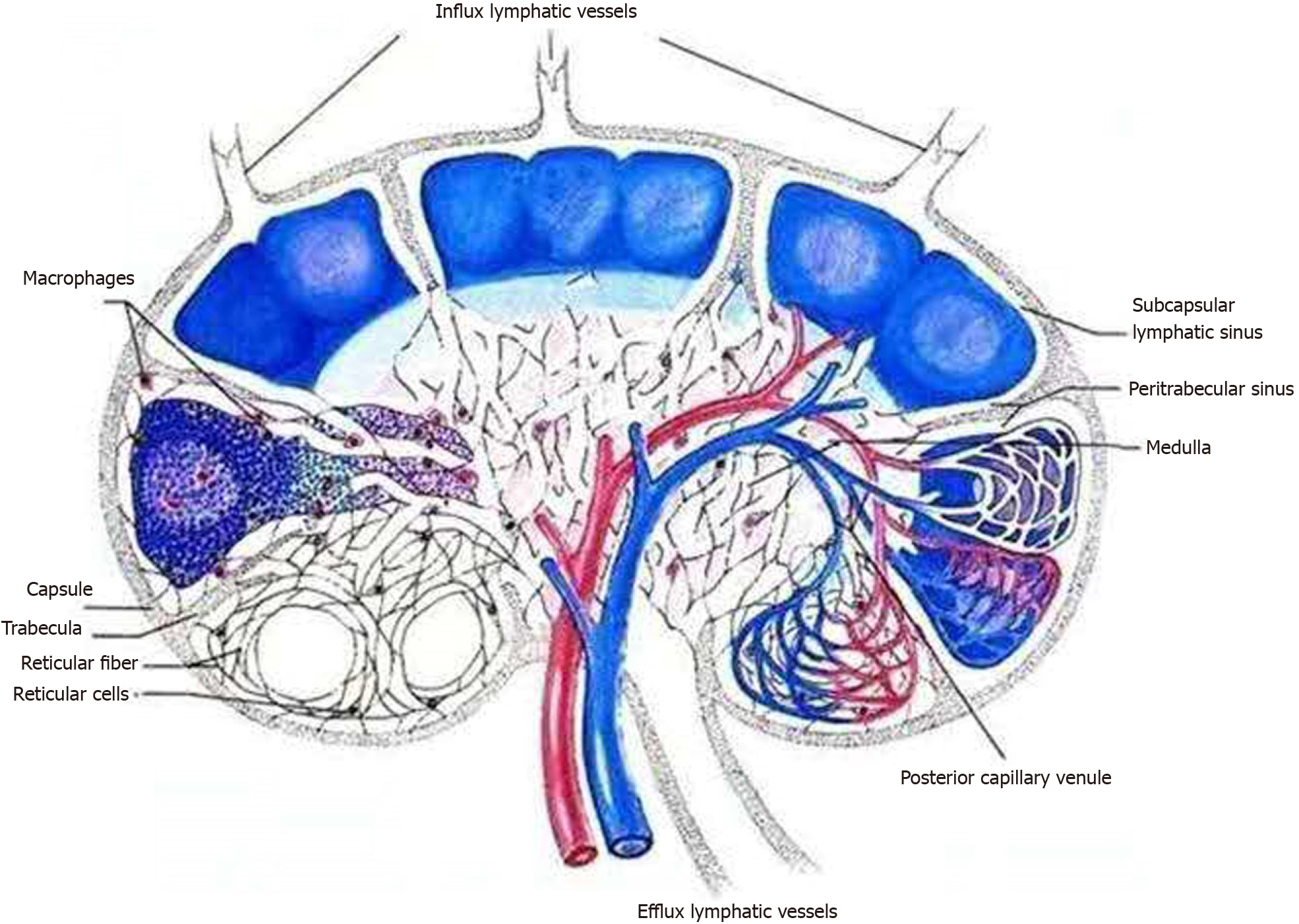

Core Tip: It is known that obstructive uropathy or occlusion of the lymphatic ducts may lead to extravasated fluids (urine or lymph) crossing the diaphragm via innate perforations or lymphatic channels. Therein, this clinical phenomenon is addressed as the “urothorax”. Among the diverse etiologies, renal lymphangiectasia is a congenital or acquired abnormality of the lymphatic system of the kidneys. Under this instance, pleural effusion of lymphoid origin may develop when the renal parenchyma is tightly compressed by a perirenal hematoma. Arguably, tight compression of the renal parenchyma may keep the draining lymphatic vessels shut but not prevent the inflow from the capsular lymph plexus. Thus, our report has for the first time described this extremely rare scenario and raises clinical awareness of the underlying passage, through which upward spread of perirenal infection could result in lung abscess.

- Citation: Lin QZ, Wang HE, Wei D, Bao YF, Li H, Wang T. Pleural effusion and ascites in extrarenal lymphangiectasia caused by post-biopsy hematoma: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(24): 6330-6336

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i24/6330.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i24.6330

The renal system has a specific pleural effusion associated with it in the form of “urothorax”, a condition where obstructive uropathy or occlusion of the lymphatic ducts leads to extravasated fluids (urine or lymph) crossing the diaphragm via innate perforations or lymphatic channels[1]. In rare cases, this pleural effusion may be caused by renal lymphangiectasia, which is a congenital or acquired disorder of the lymphatic system of the kidneys[2]. The exact etiology of this disorder remains unknown, whereas the most common hypothesis is the occlusion of draining lymphatic ducts secondary to trauma, scarring, infection, inflammation or malignant cells of the kidneys[3]. There is only one report from the American Journal of Kidney Diseases[4] describing extrinsic compression of the kidney by hemorrhage leading to extrarenal lymphangiectasia, and we hereby described such an extremely rare case with resultant pleural effusion. The study was approved by our institutional review board (No. 2020-22), and written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

A 54-year-old man was admitted for serum creatinine (Scr) elevation for 1 mo.

He initially visited a local clinic due to loss of appetite and was found to have an elevated Scr without dysuresia. Fluid infusion had indiscernible effect on the abnormal Scr and no evidence of secondary kidney disease was found. He was then referred to us, pending renal biopsy.

The patient was a capable farm hand ex ante without a known medical history.

He denied any family history of hypertension, diabetes or kidney disease.

On arrival, his blood pressure was 150/90 mmHg, and he had a slightly anemic complexion. Otherwise, physical examination yielded no remarkable findings.

Laboratory tests revealed a hemoglobin concentration of 108 g/L (reference: 130-150 g/L), platelet count of 202 × 109/L (100-300 × 109/L), plasma albumin of 41.3 g/L, Scr of 679.1 µmol/L (44.2-132.6 μmol/L), normal coagulation function including D-dimer and negative results for anti-nuclear antibody, anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibody and immunofixation electrophoresis. Screening for hepatitis B and malignancy was negative. After the routine workup, renal biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of acute tubulointerstitial nephropathy.

Plain chest X-ray was clear. Furthermore, the kidneys appeared normal on sonography without aberrant echogenicity.

Acute tubulointerstitial nephropathy.

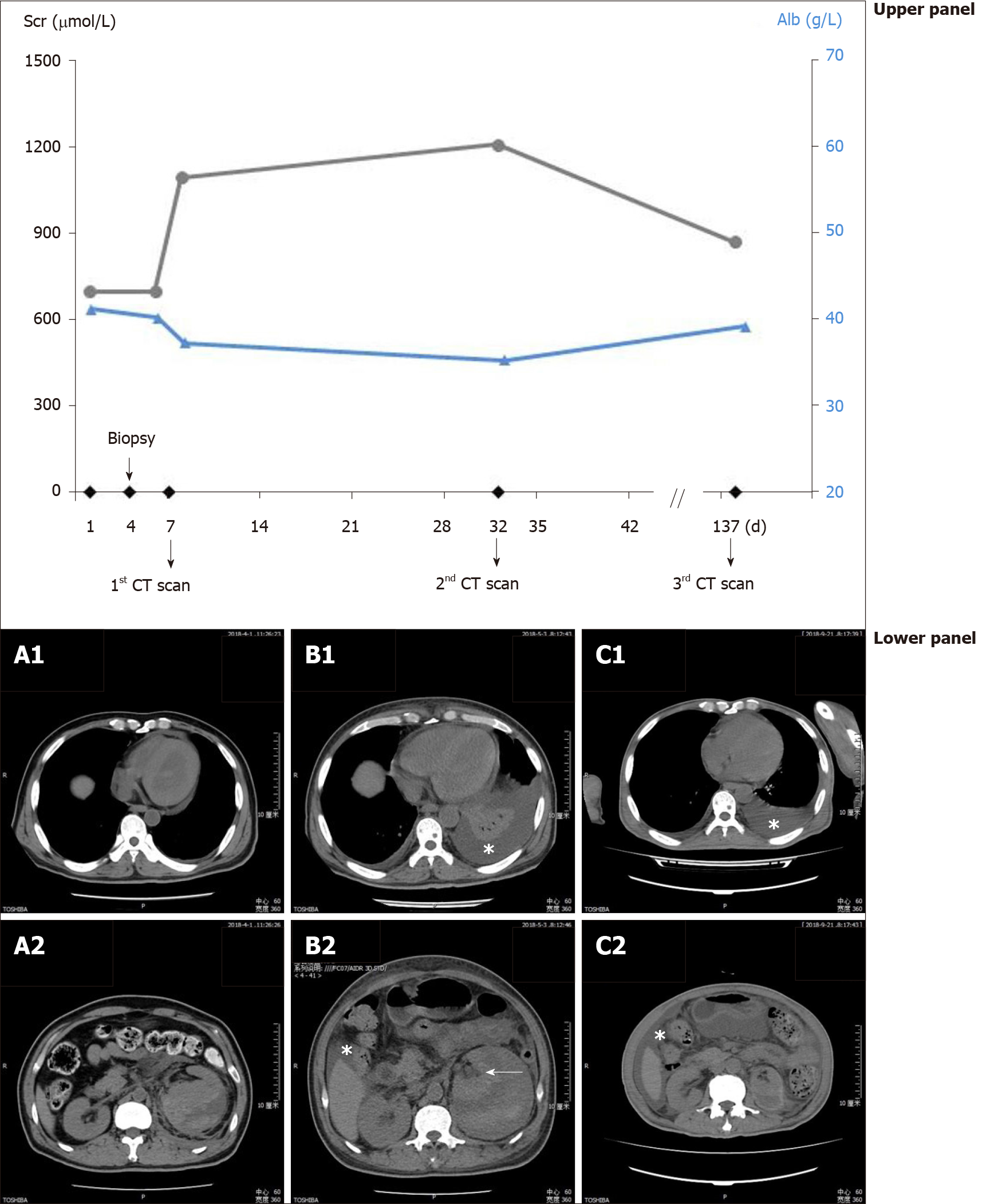

Three days after the biopsy, however, the patient experienced bleeding, which, upon clinical detection, manifested as a large perirenal hematoma without concurrent pleural effusion (Figure 1A). Laboratory tests post hoc showed a surge in the Scr level to 1094.3 µmol/L (Figure 1, upper panel), whereas the hemoglobin concentration, platelet count and plasma albumin were 56 g/L, 166 × 109/L and 36.7 g/L, respectively. Continuous renal replacement therapy was employed due to transient oliguria, and the patient’s situation was eventually stabilized by expeditious management, including selective renal arterial embolization.

While with good hemodialysis adequacy and under stringent volume control for Page kidney, computed tomography (CT) scan 1 mo later found further enlargement of the perirenal hematoma with heterogeneous hypodense fluid, massive left-sided pleural effusion and a small amount of ascites (Figure 1B). These fluid collections had a CT density of 3 Hounsfield units (HU), and drained fluid of the pleural effusion yielded a light-colored transudate with lymphocytic predominance (> 80%). Additionally, Scr remained elevated, and plasma albumin was generally stable, with a hemoglobin concentration of 97 g/L and platelet count of 240 × 109/L. Furthermore, the pleural effusion and ascites consistently showed the same HU and lymphatic nature 4 mo later (Figure 1C), accompanied by lowering of the Scr and rise in the albumin. Of note, the patient was free of pulmonary infection and cardiac dysfunction during the whole episode.

As schematically outlined in Figure 2, tight compression of the renal parenchyma may keep the draining lymphatic vessels shut but not prevent the inflow from the capsular lymph plexus. On the basis of clinical features, imaging findings and laboratory tests, the diagnosis of extrarenal lymphangiectasia was made, as classified previously[4]. The patient was then kept on hemodialysis, with a special focus on dry weight and urinary volume.

He was eventually detached from hemodialysis 10 mo after the hemorrhage and treated for chronic kidney disease stage 5, according to the “Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes” Guideline[5]. His Scr fluctuated between 300-400 µmol/L and had a daily urinary volume of approximately 1000 mL.

Renal lymphangiectasia is a rare benign disorder characterized by abnormal and ectatic lymphatic vessels within and around the kidneys. The abnormal dilatation of these lymphatic ducts arises from their failure to communicate with larger retroperitoneal lymph vessels. Although it is bilateral in nature in more than 90% of cases[2], this disorder may also be unilateral or focal[6]. The diagnosis is based mainly on imaging results, although perinephric/pleural fluid analysis and kidney biopsy are definitely helpful[2,4]. As such, imaging findings of renal lymphangiectasia may include peripelvic cysts (intrarenal lymphangiectasia) and perinephric fluid collections (extrarenal lymphangiectasia)[4,7]. However, locular cystic lesions within the renal sinuses may be absent in cases of perirenal compression of the kidney parenchyma or bilateral renal vein thrombosis[8,9]. In addition to the perinephric and/or retroperitoneal fluid collection, it may also manifest ascites and, rarely, pleural effusion.

Renal lymphangiectasia may confer pleural effusion through the passage of “urothorax”. Under such circumstances, pleural drainage usually reveals chylous fluid with lymphocytic predominance (≥ 90%)[4], while occasionally, cell staining may prove colorless at gross examination[2]. In another chance encounter supporting this finding, we recently admitted another patient on maintenance peritoneal dialysis for dyspnea on exertion. His discomfort was exacerbated after the infusion of peritoneal dialysate, and a CT scan found a large amount of right-sided pleural effusion (Supplementary Figure 1). After the addition of methylene blue to the dialysate, colored pleural drainage was observed. Indeed, urinary tract infection may spread upward and lead to lung abscess[10]. Taken together, our case highlighted a de novo morbific passage between the kidney and thorax under extraordinary conditions.

Clinically, renal lymphangiectasia is usually asymptomatic and incidentally diagnosed. When symptomatic, the most common presentations are abdominal pain (42%) and abdominal distension (21%), followed by fever, hematuria, fatigue, weight loss, hypertension and occasional deterioration in renal function[11]. A unique entity, namely, the Page kidney, was considered in this case with the associated hypertension after subcapsular hematoma, and the management required sufficient fluid control[12]. In this respect, our patients on maintenance hemodialysis generally manifested good Kt/V in both a cross-sectional study[13] and 10-year follow-up[14], and the critically ill patients receiving continuous renal replacement therapy had fine volume control[15]. Therefore, it is highly unlikely that the observed pleural effusion was derived from fluid overload. Of essential importance, caution regarding polycythemia and the associated deep venous thrombosis has been recommended in renal lymphangiectasia[2]. In this regard, a detailed description of the differential diagnosis[2] and therapeutic approach[4] is available elsewhere.

In conclusion, we reported an extremely unusual case of pleural effusion caused by extrarenal lymphangiectasia, which resulted from occlusion of the lymphatic ducts due to compression of the renal parenchyma by a hematoma. Given the paucity of pertinent knowledge, these findings may further improve our understanding of this rare disorder.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Desai DJ S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Jones GH, Kalaher HR, Misra N, Curtis J, Parker RJ. Empyema and respiratory failure secondary to nephropleural fistula caused by chronic urinary tract infection: a case report. Case Rep Pulmonol. 2012;2012:595402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bazari H, Attar EC, Dahl DM, Uppot RN, Colvin RB. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 23-2010. A 49-year-old man with erythrocytosis, perinephric fluid collections, and renal failure. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:463-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rastogi R, Rastogi UC, Sarikwal A, Rastogi V. Renal lymphangiectasia associated with chronic myeloid leukemia. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2010;21:724-727. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Wani NA, Kosar T, Gojwari T, Qureshi UA. Perinephric fluid collections due to renal lymphangiectasia. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57:347-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Floege J, Barbour SJ, Cattran DC, Hogan JJ, Nachman PH, Tang SCW, Wetzels JFM, Cheung M, Wheeler DC, Winkelmayer WC, Rovin BH; Conference Participants. Management and treatment of glomerular diseases (part 1): conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. 2019;95:268-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 35.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Surabhi VR, Menias C, Prasad SR, Patel AH, Nagar A, Dalrymple NC. Neoplastic and non-neoplastic proliferative disorders of the perirenal space: cross-sectional imaging findings. Radiographics. 2008;28:1005-1017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Varela JR, Bargiela A, Requejo I, Fernandez R, Darriba M, Pombo F. Bilateral renal lymphangiomatosis: US and CT findings. Eur Radiol. 1998;8:230-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Al-Dofri SA. Renal lymphangiectasia presented by pleural effusion and ascites. J Radiol Case Rep. 2009;3:5-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Riehl J, Schmitt H, Schäfer L, Schneider B, Sieberth HG. Retroperitoneal lymphangiectasia associated with bilateral renal vein thrombosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:1701-1703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | O'Brien JD, Ettinger NA. Nephrobronchial fistula and lung abscess resulting from nephrolithiasis and pyelonephritis. Chest. 1995;108:1166-1168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Schwarz A, Lenz T, Klaen R, Offermann G, Fiedler U, Nussberger J. Hygroma renale: pararenal lymphatic cysts associated with renin-dependent hypertension (Page kidney). Case report on bilateral cysts and successful therapy by marsupialization. J Urol. 1993;150:953-957. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sterns RH, Rabinowitz R, Segal AJ, Spitzer RM. 'Page kidney'. Hypertension caused by chronic subcapsular hematoma. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:169-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wang T, Zhang Y, Niu K, Wang L, Shi Y, Liu B. Association of the -449GC and -1151AC polymorphisms in the DDAH2 gene with asymmetric dimethylarginine and erythropoietin resistance in Chinese patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2017;44:961-964. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wang T, Li Y, Wu H, Chen H, Zhang Y, Zhou H, Li H. Optimal blood pressure for the minimum all-cause mortality in Chinese ESRD patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Biosci Rep. 2020;40:BSR20200858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wang T, Zhang Y, Li Q, Jia S, Shi C, Niu K, Liu B. Acute kidney injury in cancer patients and impedance cardiography-assisted renal replacement therapy: Experience from the onconephrology unit of a Chinese tertiary hospital. Exp Ther Med. 2017;14:5671-5677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |