Published online Nov 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i21.5474

Peer-review started: June 24, 2020

First decision: August 21, 2020

Revised: September 4, 2020

Accepted: September 29, 2020

Article in press: September 29, 2020

Published online: November 6, 2020

Processing time: 134 Days and 23.6 Hours

Benign symmetric lipomatosis (BSL) was first described by Brodie in 1846 and defined as Madelung’s disease by Madelung in 1888. At present, about 400 cases have been reported worldwide. Across these cases, surgical resection remains the recommended treatment. Here we report a case of neck BSL with concomitant thick fatty deposit in the inguinal region, which concealed the signs of a right incarcerated femoral hernia.

A 69-year-old male patient was admitted to our hospital with “abdominal pain, abdominal distension, nausea-vomiting and difficult defecation for half a month”. Moreover, he had a mass in the right inguinal region for more than 10 years. An egg-sized neck mass also developed 15 years ago and had developed into a full neck enlargement 1 year later. In addition, the patient had a history of heavy alcohol consumption for more than 40 years. With the aid of computerized tomography scan, the patient was diagnosed with BSL and a low intestinal mechanical obstruction caused by a right inguinal incarcerated hernia. Under general anesthesia, right inguinal incarcerated femoral hernia loosening and tension-free hernia repair was performed. However, this patient did not receive BSL resection. After a 1-year follow-up, no recurrence of the right inguinal femoral hernia was found. Moreover, no increase in fat accumulation was found in the neck or other areas.

Secretive intraperitoneal fat increase may be difficult to detect, but a conservative treatment strategy can be adopted as long as it does not significantly affect the quality-of-life.

Core Tip: Secretive increase of intraperitoneal fat may be difficult to detect until the appearance of abdominal symptoms is observed. A conservative treatment strategy can be selectively adopted as long as the patient’s self-perceived quality-of-life is not affected.

- Citation: Li B, Rang ZX, Weng JC, Xiong GZ, Dai XP. Benign symmetric lipomatosis (Madelung’s disease) with concomitant incarcerated femoral hernia: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(21): 5474-5479

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i21/5474.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i21.5474

Benign symmetric lipomatosis (BSL), also called Madelung’s disease, multiple symmetric lipomatosis or Launosi-Bensaude syndrome, manifests with abnormal fat distribution[1]. BSL was first described by Brodie in 1846 and defined by Madelung in 1888[2]. Alcohol withdrawal is the most effective prevention and treatment, although the pathogenesis of BSL is still unclear[3]. The disease is more common in middle-aged to elderly men and often develops in white people in the Mediterranean region or eastern Europe[4]. Nevertheless, the incidence rate of BSL is low, and at present about 400 cases have been reported worldwide with the number of cases reported in China being similar to that of other countries.

The diagnosis of BSL is primarily based on clinical characteristics and imaging examinations, particularly that of magnetic resonance imaging, to determine fat deposition. Surgical resection remains the recommended treatment. However, other treatment options are also available. The most frequently affected body part for BSL is the neck and can result in serious neck deformity, social anxiety and breathing difficulties. Here, we report a rare case of neck BSL (conservative strategy adopted) with a concomitant thick fatty deposit in the inguinal region (surgical treatment performed), which concealed the signs of an incarcerated femoral hernia.

A 69-year-old male patient was admitted to The Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanhua University with abdominal pain, abdominal distension, nausea-vomiting and difficult defecation.

The patient admitted to The Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanhua University presented with abdominal pain, abdominal distension, nausea-vomiting and difficult defecation for half a month.

The patient had a mass in the right inguinal region for more than 10 years. Moreover, an egg-sized neck mass occurred 15 years ago and gradually developed into full-neck enlargement within the following year. In addition, the patient had a history of heavy alcohol consumption for more than 40 years.

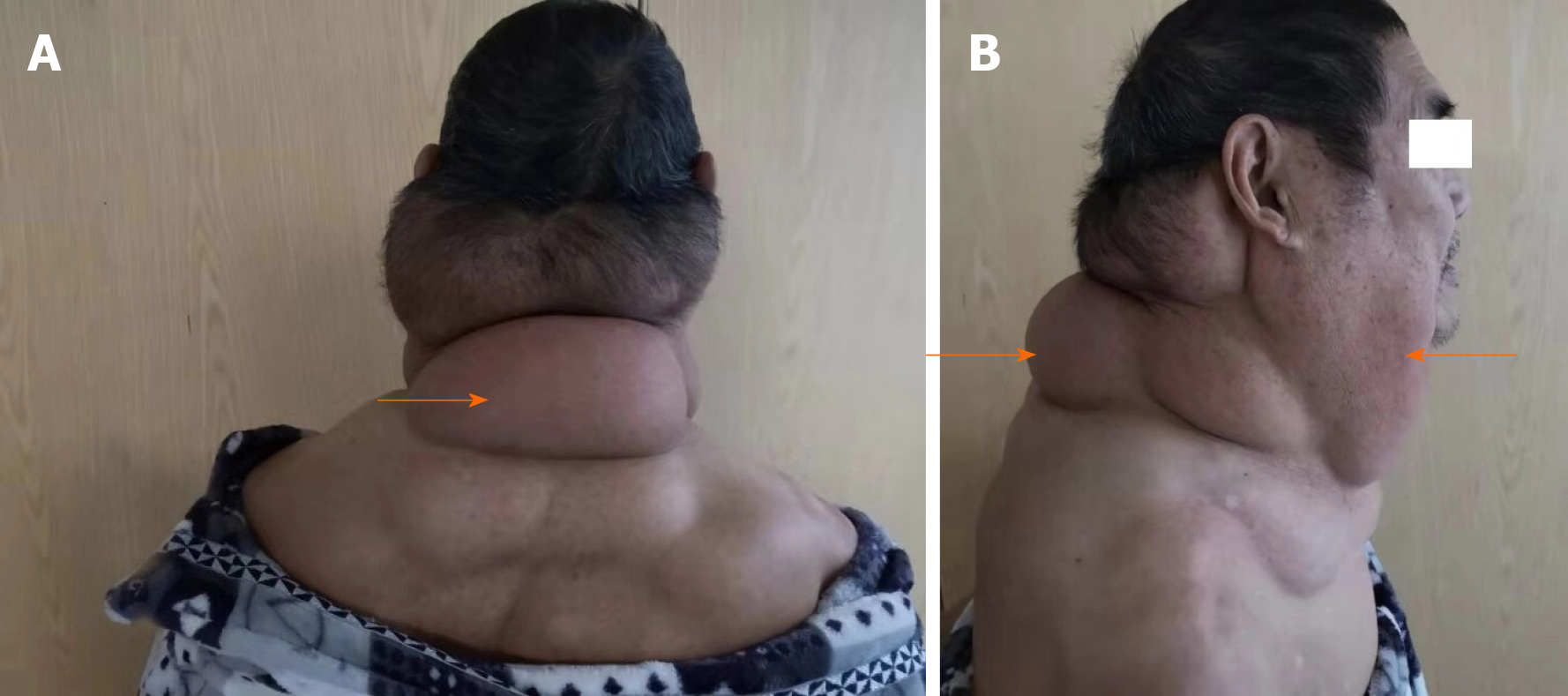

During the physical examination, a mild abdominal distension and right lower abdominal tenderness were found. Moreover, a mass was palpated in the right inguinal region, and obvious symmetrical fat accumulated in the neck and shoulder on both sides of the body.

During the laboratory examination, no special laboratory signs were found.

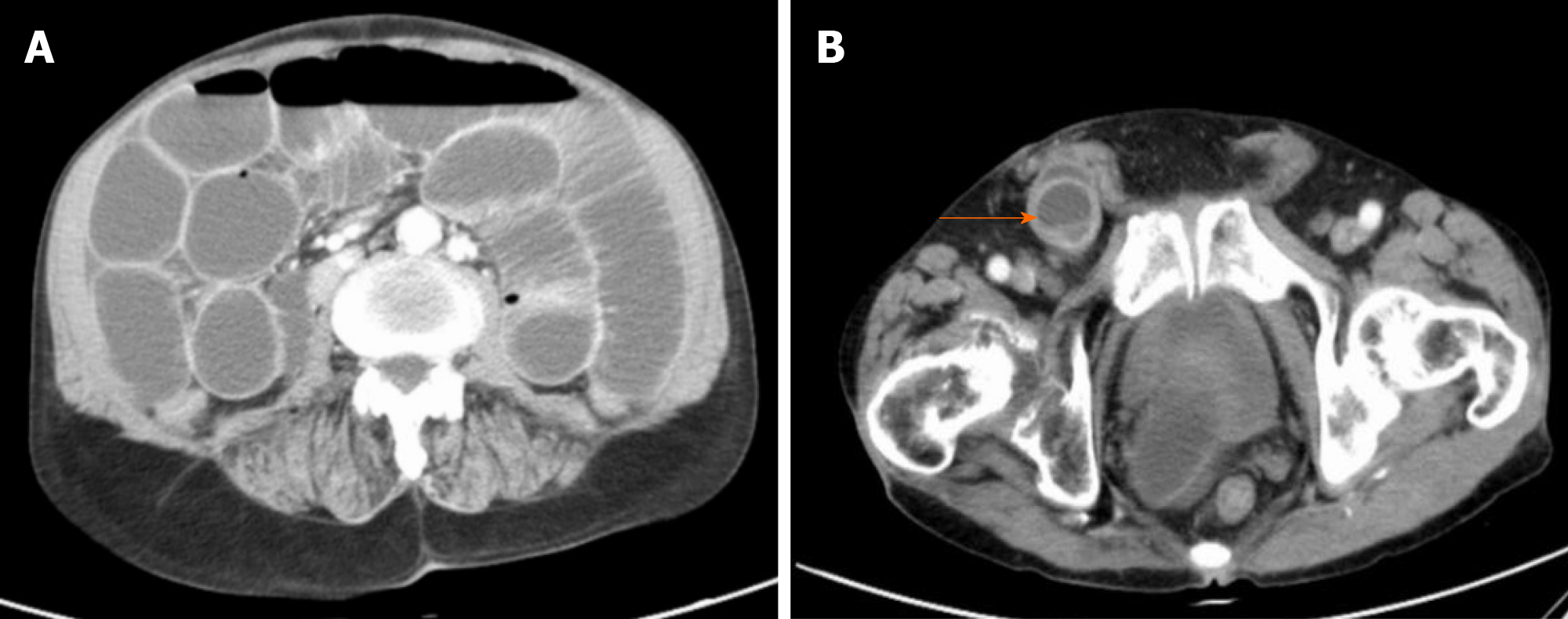

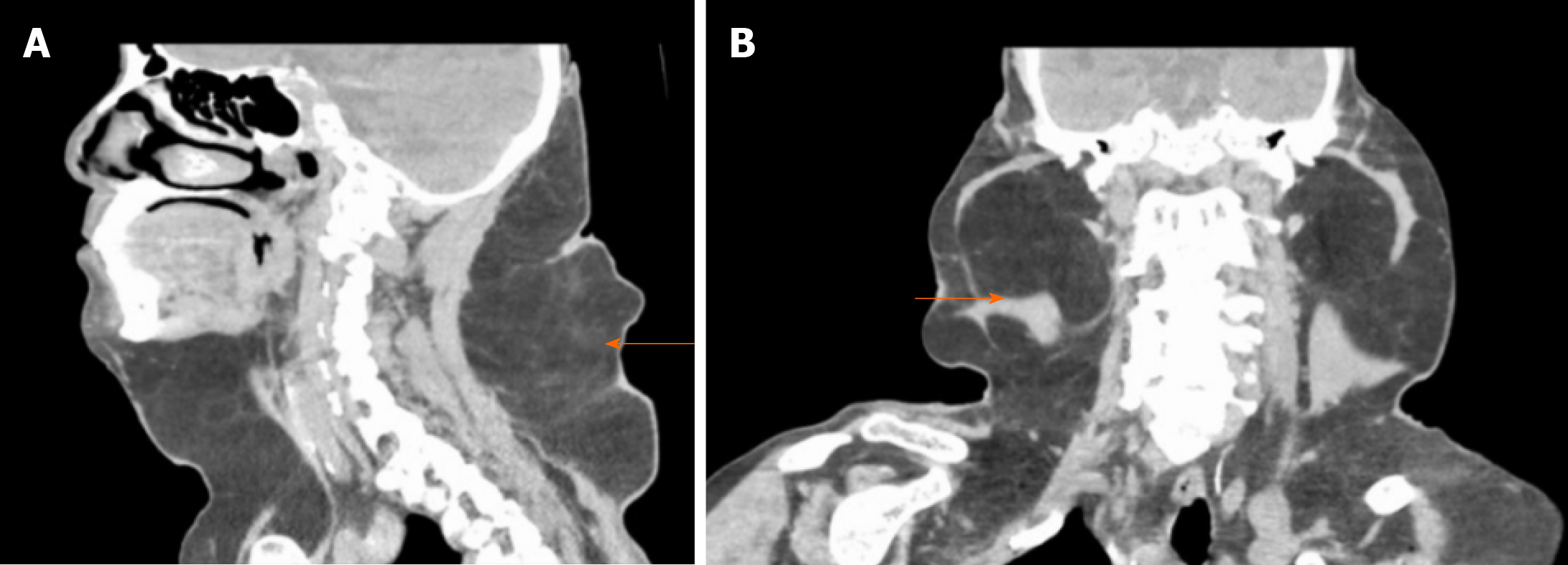

Computerized tomography (CT) showed intestinal obstruction (Figure 1A) and a mass in the right inguinal region (Figure 1B). Moreover, there was a full-neck enlargement (which gradually developed from an egg-sized neck mass that occurred 15 years ago) (Figure 2A and 2B). The CT scan of the neck showed symmetrical fat accumulation in the neck and shoulder on both sides of the body (Figure 3A and 3B).

BSL with concomitant right inguinal incarcerated hernia causing low intestinal mechanical obstruction.

Under general anesthesia, an emergency right inguinal incarcerated femoral hernia loosening and tension-free hernia repair was performed on the night of hospital admission. The hernia content proved to be that of the small intestine with congestion and edema, and no intestinal necrosis was observed. Medical repair patches (UHSL1 patches, Johnson & Johnson) were intraoperatively implanted with a connecting column connecting the upper and lower patches to reduce their movement. One patch was a rectangular piece of size 12 cm × 6 cm covering the posterior wall of the inguinal canal the other was a circular piece of size 10 cm × 6 cm covering the pectineus foramen. However, he did not receive surgery for BSL. As a standard of clinical practice, the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit for postoperative monitoring and care. He began anal exhaust when transferred to the general ward 1 d after surgery and defecated 2 d later. No complications, such as incision infection and liquefaction, occurred during hospitalization.

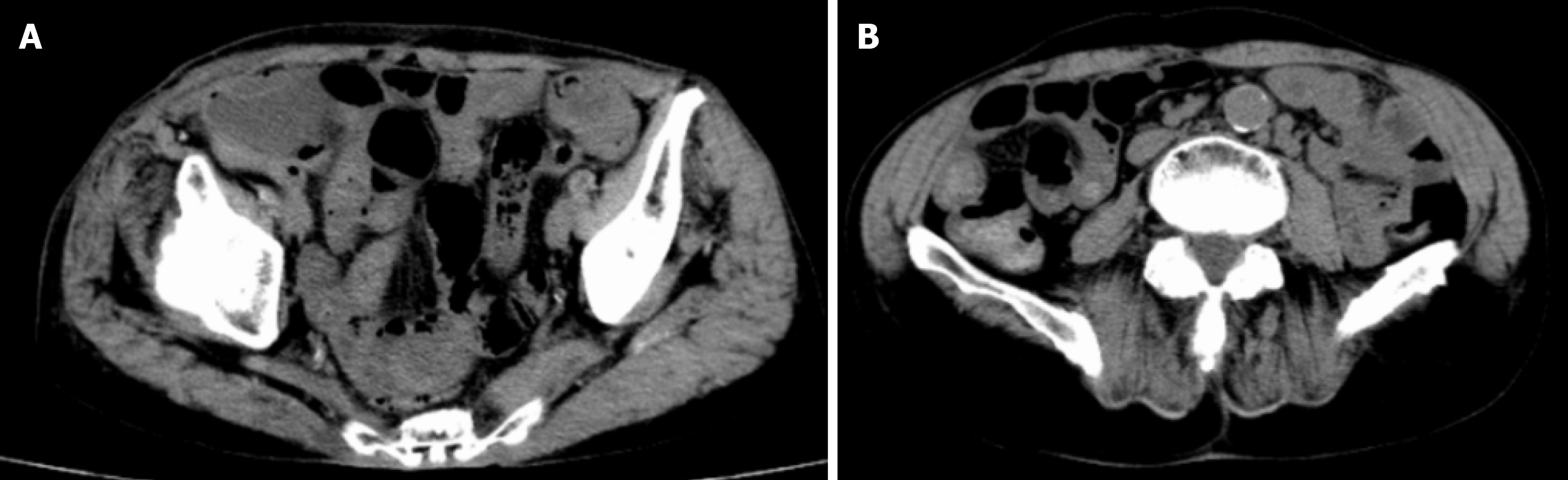

After a 1-year follow-up, no recurrence of the right inguinal femoral hernia (i.e. no intestinal protrusion in the right inguinal area and no obvious gas accumulation in the intestinal canal) was found on the CT scan (Figure 4A and 4B). Although the patient did not receive surgery or any other BSL treatment and was still mildly alcoholic, no increase in fat accumulation was observed in the neck or other areas during the follow-up period. Therefore, the secretive increase of intraperitoneal fat may be difficult to detect until the appearance of abdominal symptoms. A conservative strategy can be selectively adopted as long as the quality-of-life of the BSL patients is not affected.

BSL is mainly presented as the accumulation of a large amount of nonenveloped fatty tissue in the neck and abdomen, but most deposits are benign lesions[1]. BSL can also manifest as symmetrical fat deposition in the tongue[5], scrotum and other rare body parts[6]. Clinically, BSL is divided into three types[7]. Type I mainly develops in males where adipose tissue lesions are mainly concentrated in the neck, upper back, shoulder and upper arm, etc. Type II has no gender tendency, and the incidence rate in males and females is similar. The main lesion sites are the upper back, deltoid muscle area, upper arm, buttocks and upper thighs, and some patients have fat accumulation in the upper abdomen. Type III is a congenital accumulation of fat around the trunk. We classify the current case as Type I BSL based on the clinical manifestation of a large amount of symmetrical and painless fat tissue that accumulated in parts of the jaw, neck, occipital, shoulder, back, sternum and supraclavicular fossa. The skin color of the lesion was normal with a painless and unclear boundary, poor movement and a nodular soft mass. However, physical symptoms may occur if the trachea and local nerves are compressed by a large amount of fat accumulation.

In the present case, CT images indicated that the patient also had thick fat deposits in the inguinal region, and thus the signs of commitment incarcerated hernia were easily missed. Therefore, for such cases, the diagnosis should be confirmed based on the patient’s previous medical history, physical examination and CT imaging. What we want to emphasize is that the patient only received an emergency operation that “cured” his incarcerated hernia but did not receive any treatment for BSL, which seemed to remain stable without worsening signs. Therefore, a conservative strategy can be selectively recommended as long as the patient’s self-perceived quality-of-life is not seriously affected.

The pathogenesis of BSL is still unclear at the present time. The disease may be caused by mitochondrial dysfunction in adipose tissue, decreased activity of cytochrome C oxidase, catecholamine-induced fat deposition or a decreased number and activity of beta adrenergic receptors[3]. Moreover, about 95% of patients with BSL have a history of heavy and long-term alcohol consumption[8]. The patient in the current case indeed had a long and continuous history of heavy alcohol drinking. Currently, there is no effective treatment for BSL, although alcohol abstinence, weight control, surgical treatment (lipotomy, liposuction) and drug therapy (fenofibrate, phosphatidyl glycerin) may be beneficial[9]. As the disease progression of BSL is slow, the early consultation rate is very low and patients often seek medical treatment due to changes in their physical appearance. In some cases, surgical procedures such as liposuction and resection[10] need to be performed in order to quickly relieve symptoms, restore appearance and/or to relieve the psychological burden.

The present case exhibits the following characteristics: (1) The patient was an elderly male and not among the femoral hernia-prone population; (2) A large amount of fat accumulation in the inguinal region led to the nonobvious signs of inguinal incarcerated femoral hernia, which had been previously missed; and (3) Fat accumulation around the surgical incision potentially increased the risk of fat liquefaction. In view of the above characteristics, we recommend that a thorough clinical history and careful physical examination be necessary for the diagnosis and surgical indication of patients who present with abdominal pain or distension, nausea-vomiting and difficult defecation with obvious signs of BSL such as a neck mass or secretive symptoms such as abnormally accumulated intraperitoneal fat. Moreover, the swollen intestine trapped in the neck of the hernia sac must be intraoperatively examined for necrosis before being returned to the abdominal cavity if there is a long interval between the appearance of abdominal pain and the visit to the hospital. In addition, it is necessary for these patients to increase the frequency of dressing changes to prevent potential infection and fat liquefaction.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Coskun A, Vikey AK S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Tizian C, Berger A, Vykoupil KF. Malignant degeneration in Madelung's disease (benign lipomatosis of the neck): case report. Br J Plast Surg. 1983;36:187-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lee MS, Lee MH, Hur KB. Multiple symmetric lipomatosis. J Korean Med Sci. 1988;3:163-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kobayashi J, Nagao M, Miyamoto K, Matsubara S. MERRF syndrome presenting with multiple symmetric lipomatosis in a Japanese patient. Intern Med. 2010;49:479-482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Brea-García B, Cameselle-Teijeiro J, Couto-González I, Taboada-Suárez A, González-Álvarez E. Madelung's disease: comorbidities, fatty mass distribution, and response to treatment of 22 patients. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2013;37:409-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kang JW, Kim JH. Images in clinical medicine. Symmetric lipomatosis of the tongue. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Poggi G, Moro G, Teragni C, Delmonte A, Saini G, Bernardo G. Scrotal involvement in Madelung disease: clinical, ultrasound and MR findings. Abdom Imaging. 2006;31:503-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Enzi G. Multiple symmetric lipomatosis: an updated clinical report. Medicine. 63:56-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | González-García R, Rodríguez-Campo FJ, Sastre-Pérez J, Muñoz-Guerra MF. Benign symmetric lipomatosis (Madelung's disease): case reports and current management. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2004;28:108-112; discussion 113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Enzi G, Busetto L, Sergi G, Coin A, Inelmen EM, Vindigni V, Bassetto F, Cinti S. Multiple symmetric lipomatosis: a rare disease and its possible links to brown adipose tissue. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;25:347-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sharma N, Hunter-Smith DJ, Rizzitelli A, Rozen WM. A surgical view on the treatment of Madelung's disease. Clin Obes. 2015;5:288-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |