Published online Nov 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i21.5116

Peer-review started: June 28, 2020

First decision: August 8, 2020

Revised: August 16, 2020

Accepted: October 1, 2020

Article in press: October 1, 2020

Published online: November 6, 2020

Processing time: 130 Days and 23.6 Hours

Normal size ovarian cancer syndrome (NOCS) is a challenge for clinicians regarding timely diagnosis and management due to atypical clinical and imaging features. It is extremely rare with only a few cases reported in the literature. More data are needed to clarify its biological behavior and compare the differences with abnormal size ovarian cancer.

To assess the clinical and pathological features of NOCS patients treated in our institution in the last 10 years and to explore risk factors for relapse and survival.

Patients who were pathologically diagnosed with NOCS between 2008 and 2018 were included. Papillary serous ovarian carcinoma (PSOC) patients were initially randomly recruited as the control group. Demographics, tumor characteristics, treatment procedures, and clinical follow-up were retrospectively collected. Risk factors for progression-free survival and overall survival were assessed.

A total of 110 NOCS patients were included; 80 (72.7%) had primary adnexal carcinoma, two (1.8%) had mesotheliomas, 18 (16.4%) had extraovarian peritoneal serous papillary carcinoma, and eight (7.3%) had metastatic tumors. Carbohydrate antigen (CA)125 and ascites quantity were lower in the NOCS cohort than in the PSOC group. The only statistically significant risk factors for worse overall survival (P < 0.05) were the levels of CA199 and having fewer than six chemotherapy cycles. The 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival rates were 75.5%, 27.7%, and 13.8%, respectively.

The clinical symptoms of the NOCS group are atypical, and the misdiagnosis rate is high. Ascites cytology and laparoscopic exploration are valuable in the early diagnosis to avoid a misdiagnosis. The level of CA199 is the most important predictor of overall survival, and more than six cycles of chemotherapy contributes to the increased survival rates of NOCS patients.

Core Tip: Normal size ovarian cancer syndrome is a rare and aggressive disease with poor prognosis. Carbohydrate antigen 199 may be an effective marker to monitor disease progression, and adequate adjuvant chemotherapy should be recommended for all patients following surgery, as patients with more than six cycles of chemotherapy have increased survival rates.

- Citation: Yu N, Li X, Yang B, Chen J, Wu MF, Wei JC, Li KZ. Clinical characteristics and survival of patients with normal-sized ovarian carcinoma syndrome: Retrospective analysis of a single institution 10-year experiment. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(21): 5116-5127

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i21/5116.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i21.5116

Epithelial ovarian carcinomas, which originate from the surface epithelium of the ovary, are usually found as a large ovarian mass at diagnosis[1]. However, ovaries of normal size with disseminated peritoneal spread are clinically rare. Feuer et al[2] in 1989 first proposed the original diagnostic criteria of “normal-sized ovary carcinoma syndrome (NOCS)” as a diffuse metastatic malignant disease of the abdominal cavity of the female, with normal-sized ovaries and no site of origin assigned definitively by preoperative or intraoperative evaluation.

The early clinical manifestations of NOCS are not obvious and easy to be ignored, and the late clinical manifestations are not representative and usually include signs and symptoms like bloating and abdominal pain, which reflect a diffuse progressive abdominal condition caused by ascites[3]. Threshold for surgical exploration of an ovarian mass is currently set as a mass diameter greater than 5 cm; however, the pelvic masses of NOCS patients are less than 5 cm. Because NOCS patients have small masses and mild accompanying symptoms, which often are easily overlooked by clinicians, most patients have elevated tumor markers and massive ascites at the time of diagnosis, with the disease having reached advanced stages when treatment is initiated. Therefore, the definite diagnosis of benign ovarian lesions and tumor-like lesions and timely surgical exploration are extremely important[4]. However, it is difficult to find primary lesions by imaging examination due to its mass size (less than 5 cm × 5 cm)[5]. It was reported that computer tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging showed normal-appearing ovaries, ascites, peritoneal thickening, and mesenteric or omental involvement, which was atypical[6-9]. A recent study has demonstrated that positron emission tomography/CT (PET/CT) has a relatively high detectability of ovarian cancer and other abdominal primary cancers. PET/CT may be able to discern the site of origin, but it is expensive and not widely used[6,7]. NOCS is difficult to diagnose clinically because of its atypical clinical manifestations and imaging examination, and the misdiagnosis rate is very high. It was previously reported to be 38.2%-100%[5], which makes clinical diagnosis and selection of effective treatment very difficult[10]. Therefore, early diagnosis and timely treatment are of utmost importance to guarantee the life safety of NOCS patients, which is an urgent problem to be solved.

Primary ovarian carcinoma usually exhibits biological behavior; its growth is local at the primary lesion at first, then metastasizing to distant sites. The histology of NOCS was reported to be the same as common epithelial ovarian cancer with variable degrees of differentiation, but it has a great tendency to spread externally with no local increase[3,11]. What is the difference between the development, occurrence, and prognosis of NOCS and the abnormal size ovarian carcinoma? As NOCS is rare, studies are scarce and have relatively small sample sizes and/or short follow-up periods. Furthermore, because of its low incidence, treatment is temporarily referred to ordinary ovarian cancer, but its clinical characteristics and prognosis and the differences with abnormal size ovarian cancer are not clear. Therefore, although NOCS has been named for nearly 30 years, its biological behavior still needs evidence-based medical data for confirmation.

Therefore, we presented a retrospective review of all cases of NOCS in our medical center. Our aim was to describe the presentation and management of this rare disease and to identify important prognostic features in this cohort, in order for clinicians to achieve early accurate diagnosis and treatment for such patients in the clinic.

Between 2008 and 2018, 110 patients were diagnosed with NOCS at our institution. The Institutional Review Board of Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology approved this study protocol. In accordance with the rules of the ethics committee, this study applied for exemption from informed consent. The histological criteria of NOCS, which was modified from the criteria of Hata[5], are as follows: First, there are extensive abdominal tumors and bilateral ovaries of normal size, the surface with or without vegetation by laparotomy or transventral operation; Second, postoperative pathological examination of the ovaries or salpinx as primary carcinoma or metastasis of other organs; Third, no other primary lesions were found by preoperative imaging and surgical exploration; Fourth, no ovarian disease patient received chemotherapy or radiotherapy before surgery nor had ovarian surgery performed recently.

As a control for comparison, a total of 152 papillary serous ovarian carcinoma (PSOC) patients were recruited between 2008 and 2018 according to the following criteria: (1) There are abdominal tumors or unilateral or bilateral ovarian masses more than 5 cm before surgery; (2) Postoperative pathological examination of the ovaries as primary papillary serous ovarian carcinoma; (3) Postoperative clinic stage II to IV; and (4) No ovarian disease received chemotherapy or radiotherapy before surgery nor had ovarian surgery performed recently.

The collected clinical data included: Age, parity, symptoms, amount of ascites, preoperative carbohydrate antigen 125 (CA125) and CA199 (U/mL), surgical stage, surgery method, type of chemotherapy, and date of tumor recurrence or progression. Progression-free survival was defined as the number of months in which there was no evidence of disease upon pelvic examination and imaging examination and during which the CA125 levels had also become normal. The overall survival time was measured in months from the time of diagnosis to the date of the last follow-up or death.

All the surgical pathology slides were reviewed by two gynecologic pathologists. Tumors were reclassified according to the World Health Organization classification, and grading was conducted using the Universal Grading System by Silverberg[12,13]. The same grading system was applied to both ovarian and extraovarian peritoneal tumors.

Descriptive summary statistics were used to evaluate the demographics. Statistical analyses of the frequency data and continuous variables were performed using Fisher's exact test, Kaplan–Meier method, and Cox regression method. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. SPSS 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY, United States) was used for the statistical analyses.

The clinical characteristics of patients with NOCS are summarized in Table 1. There was no significant difference in mean age at diagnosis, median menopause times, preoperative CA199 values, and positive rate of ascites cytology between the NOCS and PSOC groups. The presenting symptoms were most commonly abdominal distension (63.6%) or abdominal pain (18.2%) in the NOCS group. However, only five women (4.5%) experienced abdominal masses in the NOCS group (mass size was less than 5 cm). Of all patients in the NOCS group, 15 patients (15.6%) were asymptomatic and diagnosed during routine gynecological examination, imaging procedures, or from high levels of CA125. In the PSOC group, the proportion of abdominal masses of patients was higher (35.5% vs 4.5%, P < 0.05), whereas those with abdominal distension and abdominal pain were fewer (58.6% vs 81.8%, P < 0.05). The preoperative CA125 values and the volume of ascites in the NOCS group were significantly lower than that in PSOC patients (1318.04 U/mL vs 1863.38 U/mL; 1658.63 mL vs 2302.24 mL, P < 0.05). In the NOCS group, 82 (74.5%) had stage III, and 28 (25.5%) had stage IV diseases.

| Characteristic, patients with data available | NOCS | PSOC | P value |

| Age in yr | 53.76 (110) | 52.61(152) | 0.400 |

| Menopausal status | 0.579 | ||

| Premenopausal | 39 (35.4) | 59 (38.8) | |

| Postmenopausal | 71 (64.6) | 93 (61.2) | |

| Initial symptoms | 0.003 | ||

| Abdominal distension | 70 (63.6) | 63 (41.4) | |

| Abdominal pain | 20 (18.2) | 26 (17.1) | |

| Mass | 5 (4.5) | 54 (35.5) | |

| Other | 15 (15.6) | 9 (5.9) | |

| CA125 in U/mL | 1318.04 | 1863.38 | 0.039 |

| CA199 in U/mL | 51.41 | 28.52 | 0.202 |

| Ascites cytology | 0.057 | ||

| Positive | 47 (88.6) | 34 (73.9) | |

| Negative | 6 (11.3) | 12 (26.1) | |

| Ascites in mL | 1658.63 | 2302.24 | 0.025 |

| Misdiagnosis rate | 23.6% | 1.32% | 0.000 |

| Survival rates | 0.179 | ||

| 1-year | 75.5% | 64.5% | |

| 3-year | 27.7% | 23.0% | |

| 5-year | 13.8% | 9.9% |

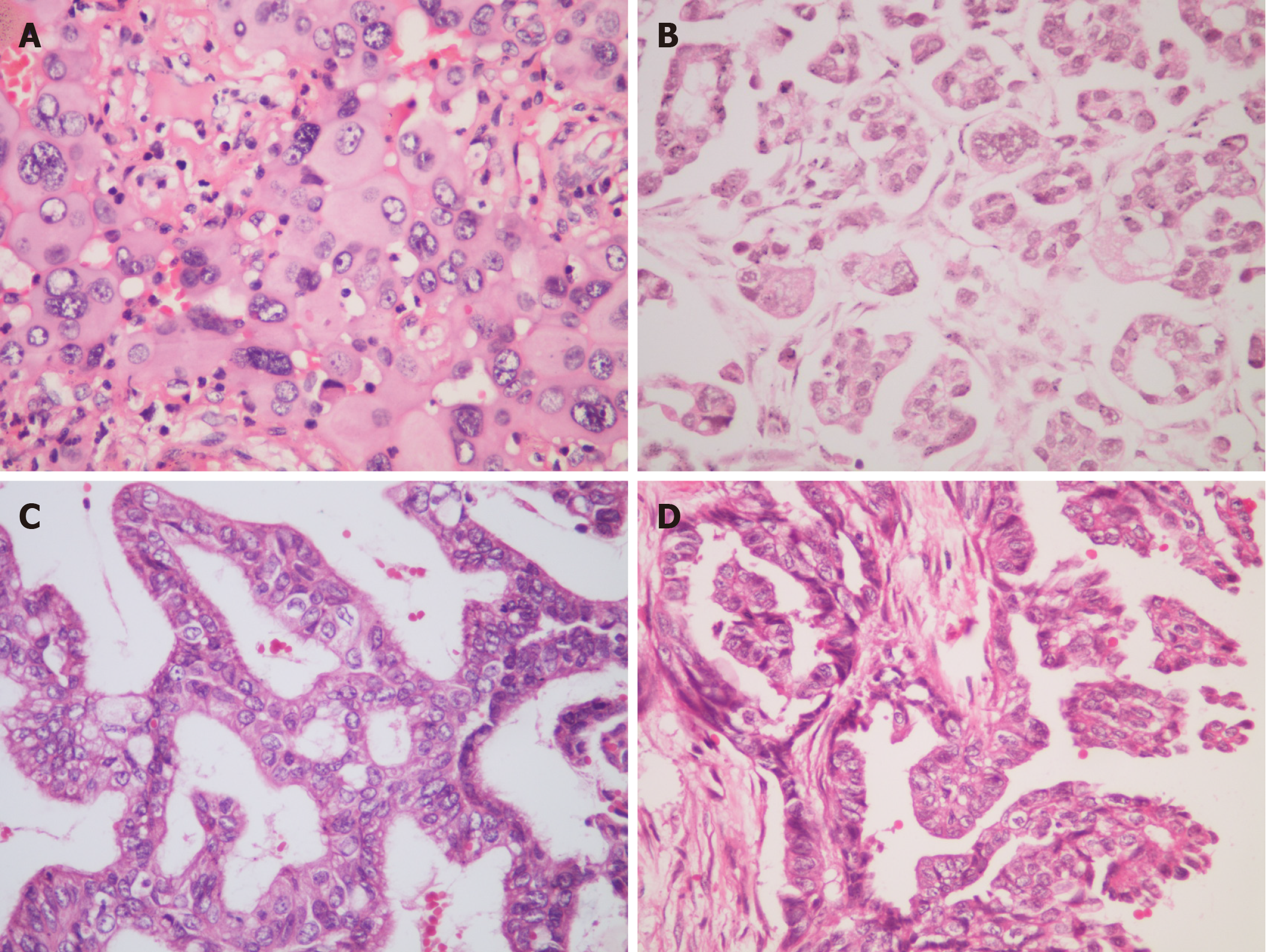

Tumor pathological characteristics are reported in Table 2, and pathological hematoxylin-eosin staining images are shown in Figure 1. NOCS was surgically and histologically reconfirmed in 110 patients. A total of 80 patients (72.7%) had primary adnexal carcinoma (65 cases of ovarian carcinoma, nine cases of salpinx carcinoma, and six cases of adnexal carcinoma), two patients (1.8%) had malignant peritoneal mesothelioma (MPM), 18 patients (16.4%) had extraovarian peritoneal serous papillary carcinoma (EPSPC), and eight patients (7.3%) had metastasis. We found that there was no significant difference in the mean age at diagnosis, menopausal status, initial symptoms, positive rate of ascites cytology preoperative, the volume of ascites, and stage in four histological subtypes. However, the preoperative CA125 values were not elevated significantly in MPM patients (36.81 U/mL) and metastatic patients (205.40 U/mL) compared to primary adnexal patients (1465.40 U/mL) and EPSPC patients (1308.14 U/mL). The preoperative CA199 values were elevated in EPSPC patients (83.87 U/mL) and metastatic patients (244.63 U/mL).

| Characteristic | Primary adnexal | MPM | EPSPC | Metastatic |

| n (%) | 80 (72.7) | 2 (1.8) | 19 (17.3) | 9 (8.2) |

| Age in yr | 53.28 (24-67) | 51.50 (45-58) | 56.42 (44-72) | 53.00 (35-66) |

| Menopausal status | ||||

| Premenopausal | 13 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Postmenopausal | 67 | 2 | 18 | 7 |

| Initial symptoms | ||||

| Abdominal distension | 52 | 2 | 12 | 4 |

| Abdominal pain | 14 | 0 | 5 | 1 |

| Mass | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Other | 11 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| CA125 in U/mL | 1465.40 | 36.81 | 1308.14 | 205.40 |

| CA199 in U/mL | 22.61 | 13.2 | 83.87 | 244.63 |

| Ascites cytology | 62 | 1 | 14 | 6 |

| Positive, n (%) | 37 (59.7) | 1 (100) | 8 (57.1) | 4 (66.7) |

| Negative, n (%) | 25 (40.3) | 0 (0) | 6 (42.9) | 2 (33.3) |

| Ascites in mL | 1717.87 | 1000 | 1500 | 1480 |

| Stage, n (%) | ||||

| III | 58 (72.5) | 2 (100) | 12 (63.2) | 6 (66.7) |

| IV | 22 (27.5) | 0 (0) | 7 (36.8) | 3 (33.3) |

| Survival rates | ||||

| 1-year | 79.5% | 100% | 64.7% | 66.7% |

| 3-year | 32.1% | 100% | 23.5% | 33.3% |

| 5-year | 20.5% | 50% | 5.9% | 22.2% |

All patients in the NOCS group underwent surgical treatment (Table 3). The majority of the patients underwent complete surgery (55.5%) with residual tumors (60.9%) in the NOCS group, and there was no significant difference between NOCS and PSOC. Sixty-one patients underwent laparoscopy surgery in the NOCS group, which was more than that in the PSOC group. In the NOCS group, adjuvant chemotherapy treatment was given to 89 patients, platinum-based chemotherapy was given to 86 patients (96.6%), nonplatinum-based chemotherapy was given to three patients, including FolFox, and so on. The majority of patients (65.9%) had more than six rounds of chemotherapy.

| Characteristic, patients with data available | NOCS | PSOC | P value |

| Initial surgery | 0.892 | ||

| Complete | 79 (71.8) | 108 (71.1) | |

| Incomplete | 31 (28.2) | 44 (28.9) | |

| Operation method | 0.000 | ||

| Laparotomy | 49 (44.5) | 112 (73.7) | |

| Laparoscopy | 61 (55.5) | 40 (26.3) | |

| Residual tumor | 0.136 | ||

| Yes | 67 (60.9) | 106 (69.7) | |

| No | 43 (39.1) | 46 (30.3) | |

| Chemotherapy | 0.000 | ||

| Platinum-based | 86 (77.3) | 142 (93.4) | |

| Nonplatinum-based | 3 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Without | 22 (20) | 10 (6.6) | |

| Chemotherapy numbers | 0.051 | ||

| ≥ 6 | 58 (65.2) | 74 (52.1) | |

| < 6 | 31 (34.8) | 68 (47.9) |

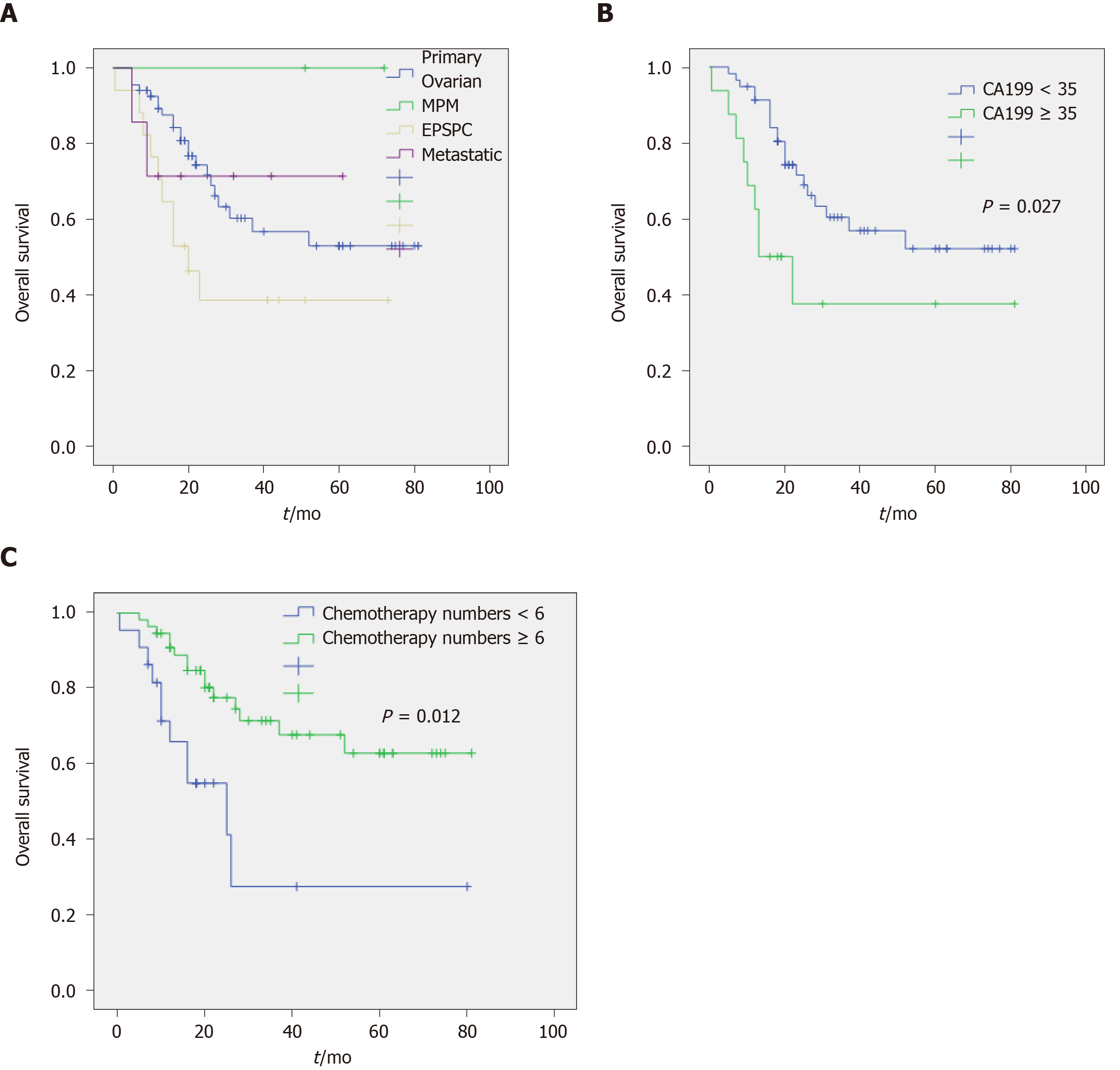

The mean survival period was 29.02 mo (median, 20.00 mo; range, 5-81 mo) in the NOCS group. As of the date of the follow-up, 60 patients (54.5%) were alive, 34 (30.9%) had died of NOCS, and 16 patients were lost to follow-up. In the whole series, the overall 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates were 75.5%, 27.7%, and 13.8%, respectively (Table 1). There was no statistically significant difference in survival rate among the primary ovarian group, EPSPC group, and metastatic group. With the exception of the MPM group, the number of patients was too small (Table 2 and Figure 2).

In the univariate Cox regression analysis (Table 4), decreased overall survival was associated with preoperative CA199 values more than 35 and having fewer than six chemotherapy cycles, whereas lower preoperative CA125 value, the volume of ascites, operation method, platinum-based chemotherapy, and residual tumors were associated with a more favorable outcome (but not significantly different). In the multivariate analysis, preoperative CA199 values more than 35 and having had fewer than six chemotherapy cycles were significant risk factors (Table 5). In addition, Kaplan–Meier curves illustrate survival outcomes (Figure 2).

| Factors | Overall survival | Progression-free survival | ||||

| Hazard ratio | 95%CI | P value | Hazard ratio | 95%CI | P value | |

| Age ≥ 50 yr | 1.314 | 0.594-2.906 | 0.500 | 0.736 | 0.290-1.871 | 0.520 |

| CA125 ≥ 100 in U/mL | 3.751 | 0.898-15.664 | 0.070 | 1.163 | 0.333-4.058 | 0.813 |

| CA199 ≥ 35 in U/mL | 2.546 | 1.156-5.608 | 0.020 | 1.778 | 0.483-6.543 | 0.387 |

| Ascites ≥ 1000 in mL | 1.954 | 0.987-3.870 | 0.055 | 1.248 | 0.567-2.747 | 0.582 |

| Stage III vs IV | 1.517 | 0.688-3.347 | 0.302 | 0.617 | 0.238-1.603 | 0.322 |

| Residual tumor | 2.348 | 0.969-5.691 | 0.059 | 1.059 | 0.431-2.599 | 0.901 |

| Complete surgery | 1.632 | 0.948-3. 061 | 0.512 | 0.842 | 0.267-2.134 | 0.534 |

| Differentiation | 0.047 | 0.000-42.817 | 0.512 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Histological subtype | 1.023 | 0.818-2.342 | 0.342 | 0.736 | 0.278-1.899 | 0.365 |

| Operation method | 0.541 | 0.268-1.091 | 0.086 | 1.114 | 0.512-2.424 | 0.785 |

| Platinum-based CT | 0.355 | 0.083-1.522 | 0.163 | 0.682 | 0.085-5.474 | 0.719 |

| Chemotherapy numbers ≥ 6 | 0.307 | 0.138-0.684 | 0.004 | 0.384 | 0.117-1.261 | 0.115 |

| Factors | Overall survival | ||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| CA125 ≥ 100 in U/mL | 0.785 | 0.093-6.589 | 0.823 |

| CA199 ≥ 35 in U/mL | 3.004 | 1.133-7.960 | 0.027 |

| Ascites ≥ 1000 in mL | 1.935 | 0.814-4.599 | 0.135 |

| Residual tumor | 1.417 | 0.492-4.078 | 0.518 |

| Chemotherapy numbers ≥ 6 | 0.313 | 0.127-0.770 | 0.012 |

| Histological subtype | 1.124 | 0.744-3.451 | 0.235 |

| Stage | 0.769 | 0.642-3.477 | 0.176 |

| Operation method | 1.213 | 0.984-3.461 | 0.115 |

We represent a fairly large cohort of patients with the rare NOCS. This group mirrors the characteristics and behavior of a typical NOCS population. Feuer et al[2] subdivided NOCS in to four categories: MPM, EPSPC, metastatic tumors, and primary ovarian carcinoma. Our study is the first large sample study examining the clinical characteristics and prognosis of NOCS.

The clinical characteristics and prognosis of the 110 patients with NOCS and 152 patients with PSOC in our study reflect the complexity of studying these diseases. As our study demonstrates, the patient characteristics of the two groups were very similar, such as age, menopausal status, preoperative CA199 values, and ascites quantity. The exception between the two groups was preoperative CA125 value. CA125 levels were elevated in most NOCS patients (89.72%) and all PSOC patients in this study, and the level in patients with NOCS was significantly lower than that in PSOC patients (median level of 1318.04 U/mL and 1863.38 U/mL, respectively). The possible explanation is that tissue sources and pathological types in the NOCS group were different; not all of them were derived from epithelial cells. Moreover, CA-125 is not tumor specific and is not typically best used to monitor disease recurrence or progression in those with a confirmed diagnosis, which is different from previous studies about PSOC[14,15]. The main initial symptoms of the NOCS group were abdominal distension (63.6%), with only 4.5% with abdominal masses (< 5 cm). In addition, the ascites quantity in the NOCS group was significantly lower than that in the PSOC group; therefore, the clinical symptoms of the NOCS group were atypical. The preoperative CA199 values were increased in some NOCS patients, but it was lower than that in the gastrointestinal tumors (51.41 U/mL vs 132.34 U/mL).

In this study, from 110 patients according to Feuer’s criteria, 80 patients (72.7%) had primary adnexal carcinoma, two patients (1.8%) had MPM, 18 patients (16.4%) had EPSPC, and eight patients (7.3%) had metastasis. There was no significant difference in age, menopausal status, clinic symptoms, and ascites quantity among the four groups, which suggested that the characteristics of the four groups were very similar. Moreover, as in previous literature, our study showed that the prognosis of the four groups was similar[3,11,16,17]. The difference of the four groups was preoperative CA125 and CA199 values and histological patterns. Preoperative CA125 was notably elevated in the primary adnexal carcinoma group and EPSPC group but not elevated in the other two groups. In addition, preoperative CA199 was elevated in the metastatic and EPSPC groups, which was not significantly elevated in the other two groups. The reason may be that the source of each group was different. However, the specificity of preoperative CA125 and CA199 was not high, and it is very limited in helping the clinical diagnosis.

We found that ascites cytology is very meaningful with high accuracy (88.6%) and easy operation. We also found that all NOCS patients were at advanced stages (III/IV) at the time of diagnosis, likely because the main clinical signs and symptoms of NOCS patients are not representative, and the primary lesions were very difficult to find by imaging examination. Therefore, it is difficult to diagnose at early stages, and the misdiagnosis rate is very high. In this study, the misdiagnosis rate was 23.6%, and the preoperative hospitalization time was 15.76 d (2-60 d), which was lower than that in previous studies[5]. This may be associated with advanced detection methods such as PET/CT, growing number of laparoscopic procedures, and physicians' increased emphasis on this disease. In NOCS, surgery remains critical as a first approach in both diagnosis and treatment, as it could reduce preoperative hospitalization time and inspection costs. It is recommended that patients with these symptoms, including bloating and abdominal pain caused by ascites as well as elevated tumor markers, should undergo laparoscopic exploration as soon as possible in order to determine a definite diagnosis to provide early treatment.

Our study is the first report of a large population-based study that showed 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates of 75.5%, 27.7%, and 13.8%, respectively, further confirming the overall poor prognosis of NOCS. In addition, these tumor patients quickly relapsed; the average recurrence time was 17.83 mo. The most important prognostic indicator was the preoperative CA199 values at presentation (hazard ratio 2.546, P < 0.05). This finding is in accordance with prior studies, which have shown a significant positive association between the levels of CA199 and mortality. A possible explanation is that patients with NOCS had advanced tumors, and the gastrointestinal tract was invaded in most of the cases or had metastatic tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. Hence, the level of CA199 is typically best used to monitor disease progression or used for prognosis.

The number of chemotherapy cycles was another important prognostic factor in this study; having more than six chemotherapy cycles was associated with a hazard ratio for mortality of 0.307 compared to having fewer than six cycles. This finding suggested that systemic chemotherapy is highly effective in NOCS patients achieving excellent survival outcomes, even during metastasis.

However, this study has several limitations. First, some statistical analyses were limited due to low numbers. Second, prospective cohorts could be performed to collect relevant data and standardize the management of these rare diseases to conceal evaluation biases related to retrospective studies performed in rare diseases[18]. Third, although our study included a large sample, some of the sub- categories had limited numbers of samples. Despite these limitations, this study is among the largest population-based studies of this rare form of cancer to date.

NOCS is a rare and aggressive disease with poor prognosis. The clinical symptoms of the NOCS group is atypical, and the misdiagnosis rate is high. Ascites cytology and laparoscopic exploration are valuable in early diagnosis to avoid a misdiagnosis. The level of CA199 is the most important predictor of overall survival, and more than six cycles of chemotherapy contributes to the increased survival rates of NOCS patients.

Epithelial ovarian cancer is known as one of the most serious gynecologic cancers and shows a higher incidence in developed countries. The general presentation of late stage epithelial ovarian cancer includes increased ovarian tumor size, however, clinicians sometimes encounter cases of advanced stage ovarian cancer without definite ovarian enlargement, known as “normal-sized ovarian carcinoma syndrome (NOCS)”.

NOCS is difficult to diagnose clinically due to its atypical clinical manifestations and imaging examination, and the misdiagnosis rate is very high. Therefore, early diagnosis and timely treatment are of utmost significance to guarantee the life safety of NOCS patients.

We describe clinical characteristics, management, and prognosis of NOCS and compare it with abnormal size ovarian cancer.

We included the NOCS patients who were pathologically diagnosed between 2008 and 2018. Papillary serous ovarian carcinoma patients were initially randomly recruited as the control group. Demographics, tumor characteristics, treatment procedures, and clinical follow-up were retrospectively collected. Risk factors for progression-free survival and overall survival were assessed.

A total of 110 NOCS patients were included, and we found that carbohydrate antigen (CA)125 and ascites quantity were lower in the NOCS cohort than in the papillary serous ovarian carcinoma group. The only statistically significant risk factors for worse overall survival (P < 0.05) were the levels of CA199 and having fewer than six chemotherapy cycles. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates were 75.5%, 27.7%, and 13.8%, respectively.

The clinical symptoms of the NOCS group are atypical, and the misdiagnosis rate is high. Ascites cytology and laparoscopic exploration are valuable in early diagnosis to avoid a misdiagnosis. The level of CA199 is the most important predictor of overall survival, and more than six cycles of chemotherapy contributes to the increased survival rates of NOCS patients.

Our study is the first large sample study on the clinical characteristics and prognosis of NOCs in the literature, providing evidence for clinical diagnosis and treatment and clinical guidance for subsequent basic research.

The authors thank everyone in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology in the Tongji Hospital of Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology for their scientific advice and encouragement.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Obstetrics and gynecology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Vetvicka V S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Ramalingam P. Morphologic, Immunophenotypic, and Molecular Features of Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Oncology (Williston Park). 2016;30:166-176. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Feuer GA, Shevchuk M, Calanog A. Normal-sized ovary carcinoma syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73:786-792. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Choi CH, Kim TJ, Kim WY, Ahn GH, Lee JW, Kim BG, Lee JH, Bae DS. Papillary serous carcinoma in ovaries of normal size: a clinicopathologic study of 20 cases and comparison with extraovarian peritoneal papillary serous carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;105:762-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Paik ES, Kim JH, Kim TJ, Lee JW, Kim BG, Bae DS, Choi CH. Prognostic significance of normal-sized ovary in advanced serous epithelial ovarian cancer. J Gynecol Oncol. 2018;29:e13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hata K, Hata T, Makihara K, Aoki S, Kitao M. Preoperative diagnostic imaging of normal-sized ovary carcinoma syndrome. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1991;35:259-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lerman H, Metser U, Grisaru D, Fishman A, Lievshitz G, Even-Sapir E. Normal and abnormal 18F-FDG endometrial and ovarian uptake in pre- and postmenopausal patients: assessment by PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:266-271. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Fletcher JW, Djulbegovic B, Soares HP, Siegel BA, Lowe VJ, Lyman GH, Coleman RE, Wahl R, Paschold JC, Avril N, Einhorn LH, Suh WW, Samson D, Delbeke D, Gorman M, Shields AF. Recommendations on the use of 18F-FDG PET in oncology. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:480-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 767] [Cited by in RCA: 753] [Article Influence: 44.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Turlakow A, Yeung HW, Salmon AS, Macapinlac HA, Larson SM. Peritoneal carcinomatosis: role of (18)F-FDG PET. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:1407-1412. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Shim SW, Shin SH, Kwon WJ, Jeong YK, Lee JH. CT Differentiation of Female Peritoneal Tuberculosis and Peritoneal Carcinomatosis From Normal-Sized Ovarian Cancer. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2017;41:32-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yong SL, Dahian S, Ramlan AH, Kang M. The diagnostic challenge of ovarian carcinoma in normal-sized ovaries: a report of two cases. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig. 2018;35:20180043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bloss JD, Brady MF, Liao SY, Rocereto T, Partridge EE, Clarke-Pearson DL; Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Extraovarian peritoneal serous papillary carcinoma: a phase II trial of cisplatin and cyclophosphamide with comparison to a cohort with papillary serous ovarian carcinoma-a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;89:148-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Shimizu Y, Kamoi S, Amada S, Hasumi K, Akiyama F, Silverberg SG. Toward the development of a universal grading system for ovarian epithelial carcinoma. I. Prognostic significance of histopathologic features--problems involved in the architectural grading system. Gynecol Oncol. 1998;70:2-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Silverberg SG. Histopathologic grading of ovarian carcinoma: a review and proposal. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2000;19:7-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zeng J, Yin J, Song X, Jin Y, Li Y, Pan L. Reduction of CA125 Levels During Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Can Predict Cytoreduction to No Visible Residual Disease in Patients with Advanced Epithelial Ovarian Cancer, Primary Carcinoma of Fallopian tube and Peritoneal Carcinoma. J Cancer. 2016;7:2327-2332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gadducci A, Menichetti A, Guiggi I, Notarnicola M, Cosio S. Correlation between CA125 levels after sixth cycle of chemotherapy and clinical outcome in advanced ovarian carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:1099-1104. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Chao KC, Chen YJ, Juang CM, Lau HY, Wen KC, Sung PL, Fang FY, Twu NF, Yen MS. Prognosis for advanced-stage primary peritoneal serous papillary carcinoma and serous ovarian cancer in Taiwan. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;52:81-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Alexander HR, Burke AP. Diagnosis and management of patients with malignant peritoneal mesothelioma. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;7:79-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ray-Coquard I, Weber B, Lotz JP, Tournigand C, Provencal J, Mayeur D, Treilleux I, Paraiso D, Duvillard P, Pujade-Lauraine E; GINECO group. Management of rare ovarian cancers: the experience of the French website "Observatory for rare malignant tumours of the ovaries" by the GINECO group: interim analysis of the first 100 patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;119:53-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |