Published online Sep 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i18.4022

Peer-review started: May 27, 2020

First decision: June 13, 2020

Revised: June 18, 2020

Accepted: August 22, 2020

Article in press: August 22, 2020

Published online: September 26, 2020

Processing time: 117 Days and 3.3 Hours

Combination chemotherapy (gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel and FOLFIRINOX) is widely used as the standard first-line treatment for pancreatic cancer. Considering the severe toxicities of combination chemotherapy, gemcitabine monotherapy (G mono) could be used as a first-line treatment in very elderly patients or those with a low Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group status. However, reports on the efficacy of G mono in patients older than 75 years are limited.

To evaluate the efficacy of G mono and combination chemotherapy by comparing their clinical outcomes in very elderly patients with pancreatic cancer.

We retrospectively analyzed 104 older patients with pancreatic cancer who underwent chemotherapy with G mono (n = 45) or combination therapy (n = 59) as a first-line treatment between 2011 and 2019. All patients were histologically diagnosed with ductal adenocarcinoma. Primary outcomes were progression-free survival and overall survival. We also analyzed subgroups according to age [65-74 years (elderly) and ≥ 75 years (very elderly)]. Propensity score matching was performed to compare the outcomes between the two chemotherapy groups.

The baseline characteristics were significantly different between the two chemotherapy groups, especially regarding age, ratio of multiple metastases, tumor burden, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status. After propensity score matching, the baseline characteristics were not significantly different between the chemotherapy groups in elderly and very elderly patients. In the elderly patients, the median progression-free survival (62 d vs 206 d, P = 0.000) and overall survival (102 d vs 302 d, P = 0.000) were longer in the combination chemotherapy group. However, in the very elderly patients, the median progression-free survival (147 d and 174 d, respectively, P = 0.796) and overall survival (227 d and 211 d, respectively, P = 0.739) were comparable between the G mono and combination chemotherapy groups. Adverse events occurred more frequently in the combination chemotherapy group than in the G mono group, especially thromboembolism (G mono vs nab-paclitaxel vs FOLFIRINOX; 8.9% vs 5.9% vs 28%, P = 0.041), neutropenia (40.0% vs 76.5% vs 84.0%, P = 0.000), and neuropathy (0% vs 61.8% vs 28.0%, P = 0.006).

In elderly patients, combination therapy is more effective than G mono. However, G mono is superior for the management of metastatic pancreatic cancer in very elderly patients.

Core Tip: Combination therapy (gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel and FOLFIRINOX) is known to be more effective than gemcitabine monotherapy in pancreatic cancer patients over 65 years of age. However, the effect in the very elderly (age 75 and over) is not well known. Our retrospective study aims to compare the efficacies of gemcitabine monotherapy vs combination therapy in very elderly pancreatic cancer patients. Our data showed that in elderly patients, combination therapy was more efficient compared to gemcitabine monotherapy. However, gemcitabine monotherapy may be a better option for managing metastatic pancreatic cancer in very elderly patients compared to combination therapy.

- Citation: Han SY, Kim DU, Seol YM, Kim S, Lee NK, Hong SB, Seo HI. First-line chemotherapy in very elderly patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer: Gemcitabine monotherapy vs combination chemotherapy. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(18): 4022-4033

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i18/4022.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i18.4022

Pancreatic cancer is known to have one of the lowest five year survival rates of all malignancies; specifically, the five year survival rate of metastatic cancer is less than 3%[1]. The median age at diagnosis of pancreatic cancer is approximately 70 years, and 30%-40% of patients are diagnosed after the age of 75 years[2-4]. Systemic palliative chemotherapy still plays an important role in metastatic pancreatic cancer to increase survival. Therefore, it is important to select an appropriate chemotherapy regimen for older patients.

Gemcitabine monotherapy (G mono) has been an important treatment for a long time. Recently, as the efficacy of new combination chemotherapies (such as gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel [GA] and modified FOLFIRINOX [FFX]) have been revealed, G mono has been used as a primary treatment[5-7]. Currently, G mono is used in older patients or those with low Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status. Older patients usually receive G mono because their performance status may be poor. A meta-analysis of chemotherapy in older patients with pancreatic cancer showed that combination therapy is more effective than G mono[8]. However, most of the studies in the meta-analysis focused on patients older than 65 years, not on very elderly patients, such as those older than 75 years. Moreover, a pivotal trial also did not focus on very elderly patients. The modified FFX trial[5] excluded patients 76 years or older, and the GA trial[6] enrolled patients with a median age of 63 years, which is below the mean age at which pancreatic cancer is diagnosed. In the Joint Committee of the Japan Gerontological Society and the Japan Geriatrics Society, 75 years was defined as old age and 65-74 years as the pre-old age range[9]. As the proportion of patients over the age of 75 years diagnosed with pancreatic cancer is high, more studies are needed to evaluate the efficacy of chemotherapy in very elderly patients.

In the present study, we retrospectively evaluated the outcomes of G mono vs combination chemotherapy in elderly (65-74 years old) and very elderly (≥ 75 years old) patients with pancreatic cancer.

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer and included those who received either G mono or combination chemotherapy (GA or FFX) as first-line chemotherapy between January 2011 and December 2019 at the Pusan National University Hospital, Busan, Korea. All patients were histologically diagnosed with ductal adenocarcinoma. Patients younger than 65 years and those who had previously undergone surgical resection were excluded. This study was performed in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration (revised in 2013), and the study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Pusan National University (IRB No. H-2005-019-091).

G mono consisted of an intravenous infusion of gemcitabine at a dose of 1000 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15, every 4 wk[10]. GA therapy consisted of a 30 min intravenous infusion of GA at a dose of 125 mg/m2, followed by gemcitabine at a dose of 1000 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 administered every 4 wk, as described in the Metastatic Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma Clinical Trial trial[6]. Modified FFX therapy consisted of a sequence of a 2 h intravenous infusion of oxaliplatin at 85 mg/m2, a 90 min intravenous infusion of irinotecan at 180 mg/m2, a 2 h infusion of leucovorin at 400 mg/m2, an intravenous bolus of 5-fluorouracil at 400 mg/m2, and a 46 h continuous infusion of 5-fluorouracil at 2400 mg/m2 administered every 2 wk[5]. Tumor response was assessed every 2-3 mo using computed tomography and graded according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, version 1.1. Moreover, tumor burden before and after chemotherapy was evaluated according to the criteria of the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors. Up to five lesions were measured from the largest lesions, and up to two lesions were measured per organ. All available patients were followed-up for at least 6 mo (excluding those lost during the follow-up). Patients who were lost during the follow-up period were analyzed with the assumption that there was disease progression on the last visit date or death.

The primary outcomes of the study were progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in patients who were treated with G mono and combination chemotherapy. Secondary outcomes were the safety and feasibility of each regimen. Subgroup analysis was performed according to age in elderly (65-74 years) and very elderly (≥ 75 years) patients.

The baseline characteristics of the G mono and combination chemotherapy groups were heterogeneous. Moreover, in each age group, the baseline characteristics were different. In the elderly group (65-74 years), age, the proportion of sex, body weight, height, ratio of multiple metastases, tumor burden, ECOG performance status, and albumin were significantly different. In the very elderly group, ECOG performance status, platelet level, and albumin level were significantly different. To eliminate this disparity, we performed propensity scoring matching. Age, sex, ratio of multiple metastases, tumor burden, ECOG performance status, and albumin were used for propensity score matching in the elderly group. ECOG performance status, tumor burden, and albumin were used for propensity score matching in the very elderly group. Supplementary Table 1 shows that Ca19-9 and the neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio were the most important prognostic factors. Hence, we especially tried to adjust for these variables similarly.

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS statistical software, version 22.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, United States). Categorical data are summarized by frequency and percentage, and differences were analyzed using the χ² test or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous data are presented as means ± SD, and the two groups were compared using the t-test. When the number of patients was small, medians with 95% confidence intervals (CI) are presented, and the two groups were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. PFS and OS were assessed using medians with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and the log-rank test. Statistical significance was considered for P values < 0.05.

Before propensity score matching: The baseline characteristics of the 104 patients are summarized in Table 1. Unless otherwise indicated, the following data are presented with the G mono group listed first, followed by the combination chemotherapy group. In the elderly and very elderly groups, baseline characteristics were significantly different between both chemotherapy groups. In the elderly group, 25 patients were treated with G mono, and 49 were treated with combination chemotherapy. The mean patient age (70.9 ± 3.2 years vs 69.2 ± 2.7 years, P = 0.020), the proportion of men (40.0% vs 81.6%, P = 0.000), the number of metastases >2 (72.0% vs 46.9%, P = 0.041), tumor burden (81.8 ± 43.3 vs 61.4 ± 32.5 mm, P = 0.025), ECOG performance status (ECOG 0/1/2, 20%/56%/24% vs 44.9%/49.0%/6.1%, P = 0.007), and albumin (3.6 ± 0.7 mg/dL vs 4.0 ± 0.5 mg/dL, P = 0.005) were significantly different between the two chemotherapy groups. In the very elderly group, 20 patients were treated with G mono, and 10 were treated with combination chemotherapy. ECOG performance status (ECOG 0/1/2, 10%/50%/40% vs 40%/50%/10%, P = 0.027), platelet count [191.5 (168.5–217.5) × 103/µL vs 243.5 (205.1–291.3) × 103/µL, P = 0.028], and albumin [3.5 (3.2–3.8) mg/dL vs 4.3 (3.9–4.5) mg/dL, P = 0.001] were significantly different between the two chemotherapy groups.

| Variable | Elderly group: 65-74 yr | Very elderly group: 75+ yr | ||||

| Gemcitabine mono, | GA and FOLFIRINOX, | P value | Gemcitabine mono, | GA and FOLFIRINOX, | P value | |

| Age in year | 70.9 ± 3.2 | 69.2 ± 2.7 | 0.020a | 77.5 (76.8-78.9) | 76.5 (75.6-78.8) | 0.397 |

| Male | 10 (40.0) | 40 (81.6) | 0.000a | 14 (70.0) | 7 (70.0) | 0.999 |

| Body weight in kg | 54.8 ± 9.0 | 59.8 ± 8.8 | 0.026a | 56.0 (43.1-62.7) | 54.3 (49.1-68.3) | 0.856 |

| Height in m | 1.58 ± 0.09 | 1.65 ± 0.08 | 0.001a | 1.63 (1.57-1.67) | 1.62 (1.56-1.69) | 0.979 |

| Body mass index in kg/m2 | 22.0 ± 2.7 | 22.1 ± 3.0 | 0.977 | 22.1 (20.7-23.5) | 21.6 (19.9-24.2) | 0.775 |

| Metastasis no > 2 | 18 (72.0) | 23 (46.9) | 0.041a | 13 (65.0) | 4 (40.0) | 0.206 |

| Site of metastasis | ||||||

| Liver | 18 (72.0) | 30 (61.2) | 0.256 | 12 (60.0) | 3 (30.0) | 0.130 |

| Peritoneal carcinomatosis | 10 (40.0) | 20 (40.8) | 0.574 | 6 (30.0) | 4 (40.0) | 0.599 |

| Lung | 5 (20.0) | 9 (18.4) | 0.548 | 4 (20.0) | 2 (20.0) | 0.999 |

| Primary tumor site | 0.671 | 0.467 | ||||

| Head | 10 (40.0) | 26 (53.1) | 9 (45.0) | 3 (30.0) | ||

| Body | 10 (40.0) | 11 (22.4) | 5 (25.0) | 3 (30.0) | ||

| Tail | 5 (20.0) | 12 (24.5) | 6 (30.0) | 4 (40.0) | ||

| Biliary stenting due to obstruction | 11 (44.0) | 20 (40.8) | 0.796 | 6 (30.0) | 3 (30.0) | 0.999 |

| Tumor burden | 81.8 ± 43.3 | 61.4 ± 32.5 | 0.025a | 81.5 (21.0-159.0) | 50.0 (15.0-225.0) | 0.109 |

| ECOG performance status | 0.007a | 0.027a | ||||

| 0 | 5 (20.0) | 22 (44.9) | 2 (10.0) | 4 (40.0) | ||

| 1 | 14 (56.0) | 24 (49.0) | 10 (50.0) | 5 (50.0) | ||

| 2 | 6 (24.0) | 3 (6.1) | 8 (40.0) | 1 (10.0) | ||

| Diabetes | 13 (52.0) | 24 (49.0) | 0.809 | 7 (35.0) | 2 (20.0) | 0.416 |

| Hypertension | 10 (40.0) | 18 (36.7) | 0.788 | 9 (45.0) | 2 (20.0) | 0.193 |

| Laboratory findings | ||||||

| White blood cell as /μL | 6648.0 ± 2411.7 | 6793.5 ± 2606.2 | 0.817 | 8175.0 (6432.4-10546.6) | 7985.0 (5824.6-9631.4) | 0.880 |

| Platelet as 103/μL | 197.1 ± 68.0 | 244.6 ± 124.7 | 0.081 | 191.5 (168.5-217.5) | 243.5 (205.1-291.3) | 0.028a |

| N/L ratio | 3.9 ± 3.0 | 3.4 ± 2.8 | 0.532 | 3.91 (3.23-6.49) | 2.19 (1.22-4.09) | 0.055 |

| Platelet/lymphocyte ratio | 159.2 ± 74.5 | 166.6 ± 90.9 | 0.724 | 125.6 (120.5-198.4) | 136.1 (94.3-176.3) | 0.559 |

| C-related protein in mg/dL | 1.9 ± 3.0 | 1.1 ± 1.9 | 0.175 | 1.22 (0.96-4.72) | 0.75 (0.12-3.04) | 0.448 |

| Albumin in g/dL | 3.6 ± 0.7 | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 0.005a | 3.5 (3.2-3.8) | 4.3 (3.9-4.5) | 0.001a |

| Total bilirubin in mg/dL | 0.98 ± 1.10 | 1.31 ± 2.10 | 0.464 | 0.49 (0.42-0.78) | 0.41 (-0.03-2.14) | 0.948 |

| CA 19-9 in U/mL | 3448.1 ± 8082.3 | 11073.9 ± 55832.2 | 0.501 | 666.4 (-2198.6-21079.9) | 341.7 (-11731.7-33174.5) | 0.328 |

Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics after propensity score matching. In the elderly group, 50 patients were analyzed; 25 patients each received G mono and combination chemotherapy. There was no significant difference between the two groups regarding mean patient age (70.9 ± 3.2 years and 70.5 ± 2.6 years, respectively, P = 0.626), number of metastases > 2 (72% and 64%, respectively, P = 0.554), tumor burden (81.8 ± 43.3 mm and 68.0 ± 34.4 mm, respectively, P = 0.217), and ECOG performance status (ECOG 0/1/2, 10%/50%/40% and 40%/48%/12%, respectively, P = 0.101). In the very elderly group, 20 patients were analyzed; 10 patients each underwent G mono and combination chemotherapy. There was no significant difference between the two groups regarding mean patient age [77.0 (75.9-78.5) years and 76.5 (75.6-78.8) years, respectively, P = 0.853], number of metastases >2 (40% and 40%, respectively, P = 0.999), tumor burden (67.5 [44.1–98.7] and 50.0 [23.5–109.9] mm, respectively, P = 0.436), and ECOG performance status (ECOG 0/1/2, 20%/40%/40% and 40%/50%/10%, respectively, P = 0.145).

| Variable | Elderly group: 65-74 yr | Very elderly group: 75+ yr | ||||

| Gemcitabine mono, n = 25 | GA and FOLFIRINOX, n = 25 | P value | Gemcitabine mono, n = 10 | GA and FOLFIRINOX, n = 10 | P value | |

| Age in year | 70.9 ± 3.2 | 70.5 ± 2.6 | 0.626 | 77.0 (75.9-78.5) | 76.5 (75.6-78.8) | 0.853 |

| Male | 10 (40.0) | 16 (64.0) | 0.093 | 7 (70.0) | 7 (70.0) | 0.999 |

| Body weight in kg | 54.8 ± 9.0 | 59.7 ± 8.8 | 0.062 | 54.8 (49.4-65.5) | 54.3 (49.1-68.3) | 0.762 |

| Height in m | 1.58 ± 0.09 | 1.62 ± 0.09 | 0.060 | 1.64 (1.51-1.68) | 1.62 (1.56-1.69) | 0.696 |

| Body mass index in kg/m2 | 22.0 ± 2.7 | 22.6 ± 2.7 | 0.438 | 22.6 (20.7-24.4) | 21.6 (19.9-24.2) | 0.633 |

| Metastasis no > 2 | 18 (72.0) | 16 (64.0) | 0.554 | 4 (40.0) | 4 (40.0) | 0.999 |

| Site of metastasis | ||||||

| Liver | 18 (72.0) | 16 (64.0) | 0.554 | 5 (50.0) | 3 (30.0) | 0.388 |

| Peritoneal carcinomatosis | 10 (40.0) | 7 (28.0) | 0.381 | 3 (30.0) | 4 (40.0) | 0.660 |

| Lung | 5 (20.0) | 7 (28.0) | 0.518 | 0 (0) | 2 (20.0) | 0.151 |

| Primary tumor site | 0.603 | 0.464 | ||||

| Head | 10 (40.0) | 14 (56.0) | 5 (50.0) | 3 (30.0) | ||

| Body | 10 (40.0) | 5 (20.0) | 2 (20.0) | 3 (30.0) | ||

| Tail | 5 (20.0) | 6 (24.0) | 3 (30.0) | 4 (40.0) | ||

| Biliary stenting due to obstruction | 11 (44.0) | 12 (48.0) | 0.782 | 4 (40.0) | 3 (30.0) | 0.660 |

| Tumor burden | 81.8 ± 43.3 | 68.0 ± 34.4 | 0.217 | 67.5 (44.1-98.7) | 50.0 (23.5-109.9) | 0.436 |

| ECOG Performance status | 0.101 | 0.145 | ||||

| 0 | 5 (20.0) | 10 (40.0) | 2 (20.0) | 4 (40.0) | ||

| 1 | 14 (56.0) | 12 (48.0) | 4 (40.0) | 5 (50.0) | ||

| 2 | 6 (24.0) | 3 (12.0) | 4 (40.0) | 1 (10.0) | ||

| Diabetes | 13 (52.0) | 15 (60.0) | 0.578 | 5 (50.0) | 2 (20.0) | 0.177 |

| Hypertension | 10 (40.0) | 10 (40.0) | 0.999 | 6 (60.0) | 2 (20.0) | 0.074 |

| Laboratory findings | ||||||

| White blood cell as /μL | 6648.0 ± 2411.7 | 7122.4 ± 2777.8 | 0.522 | 6195.0 (4330.2-11393.8) | 7985.0 (5824.6-9631.4) | 0.912 |

| Platelet as 103/μL | 197.1 ± 68.0 | 248.7 ± 125.8 | 0.078 | 171.5 (140.7-236.5) | 243.5 (205.1-291.3) | 0.089 |

| N/L ratio | 3.9 ± 3.0 | 3.8 ± 2.9 | 0.937 | 2.32 (1.60-5.36) | 2.20 (1.22-4.09) | 0.684 |

| Platelet/lymphocyte ratio | 159.2 ± 74.5 | 172.8 ± 102.3 | 0.594 | 121.6 (93.2-165.9) | 136.1 (94.3-176.3) | 0.853 |

| C-related protein in mg/dL | 1.9 ± 3.0 | 1.7 ± 2.4 | 0.800 | 0.45 (0.18-2.00) | 0.75 (0.12-3.04) | 0.796 |

| Albumin in g/dL | 3.6 ± 0.7 | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 0.182 | 4.0 (3.7-4.1) | 4.3 (3.9-4.5) | 0.123 |

| Total bilirubin in mg/dL | 0.98 ± 1.10 | 1.7 ± 2.4 | 0.246 | 0.44 (0.30-0.63) | 0.41 (-0.03-2.14) | 0.684 |

| CA 19-9 in U/mL | 3448.1 ± 8082.3 | 5260.9 ± 20304.3 | 0.681 | 482.9 (78.7-3297.4) | 341.7 (-11731.7-33174.5) | 0.393 |

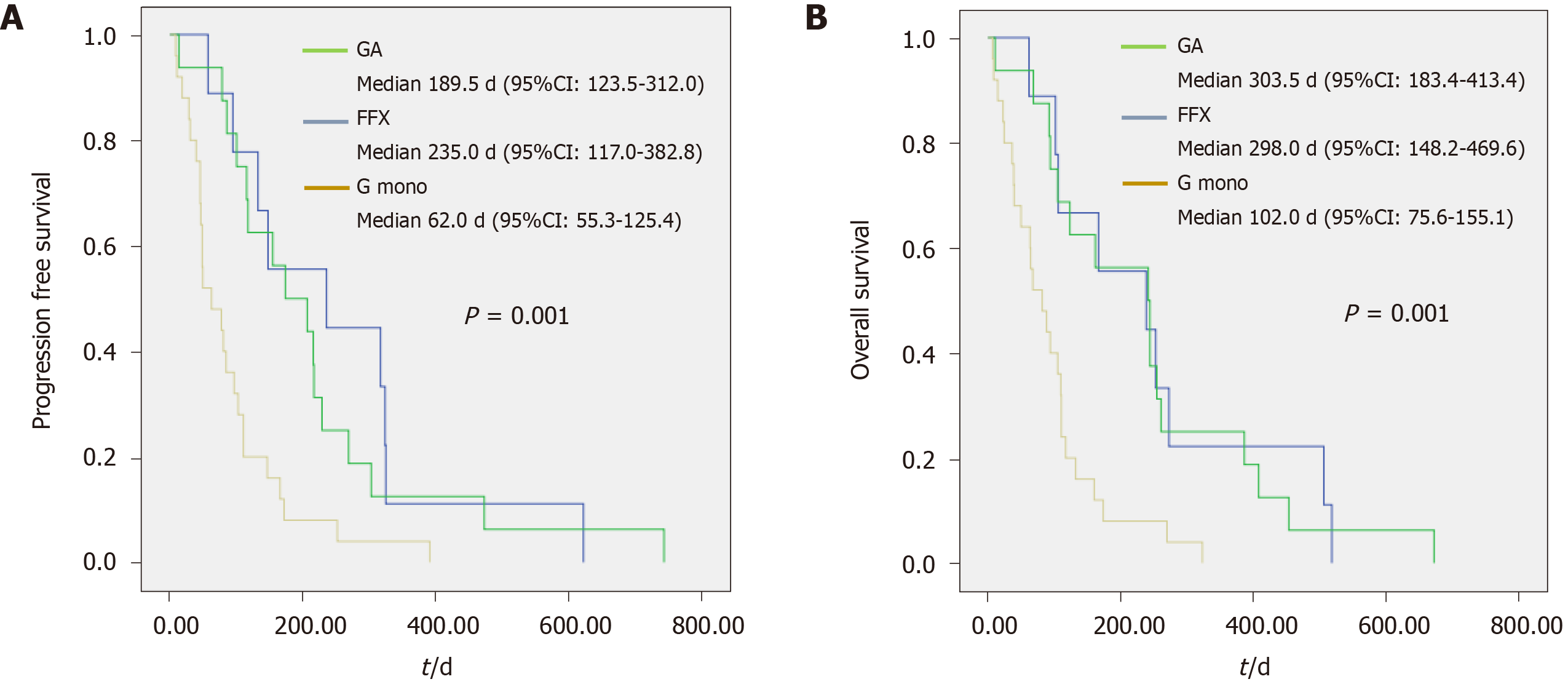

Table 3 shows the efficacy of each regimen according to age. In the elderly group, when comparing the best responses for each regimen, the disease control rate was slightly higher in the combination chemotherapy group than in the G mono group; however, the difference was not significant (58.8% and 79.2%, respectively, P = 0.166). Regarding the proportion of tumor burden change before and after chemotherapy, combination chemotherapy was more effective than G mono (11.4 ± 22.8% vs -4.1 ± 23.1%, P = 0.049). PFS [62.0 (55.3–125.4) d vs 206.0 (158.1–300.5) d, P = .000] and OS [102.0 (75.6–155.1) d vs 302.0 (215.9–388.4) d, P = 0.000] also showed that combination therapy was significantly more effective than G mono. The mean number of chemotherapy days was also longer in the combination chemotherapy group (56 vs 112 d, P = 0.001). The proportions of patients with a reduced dose of the regimen (40% vs 72%, P = 0.022) and who underwent second-line chemotherapy (12% vs 48%, P = 0.005) were higher in the combination chemotherapy group. TS-1 (tegafur/ gimeracil/oteracil; 24%) and G mono (16%) were commonly used as second-line chemotherapy in patients in the combination chemotherapy group. Figure 1 shows the median PFS (G mono vs GA vs FFX; 62 d vs 189.5 d vs 235 d, P = 0.001) and median OS (102 vs 303.5 vs 298 d, P = 0.001) for each regimen in the elderly group.

| Elderly group: 65-74 yr | Very elderly group: 75+ yr | |||||

| Gemcitabine mono, n = 25 | GA and FOLFIRINOX, n = 25 | P value | Gemcitabine mono, n = 10 | GA and FOLFIRINOX, | P value | |

| Chemo response1 | 0.069 | 0.355 | ||||

| PR | 0 (0.0) | 3 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| SD | 10 (67.7) | 16 (66.7) | 6 (60.0) | 8 (80.0) | ||

| PD | 7 (41.2) | 5 (20.8) | 4 (40.0) | 2 (20.0) | ||

| DCR, PR + SD | 10 (58.8) | 19 (79.2) | 0.166 | 6 (60.0) | 8 (80.0) | 0.355 |

| Tumor burden change, % | 11.4 ± 22.8 | -4.1 ± 23.1 | 0.049a | 7.0 (-9.1-39.7) | 3.5 (-5.9-13.4) | 0.633 |

| Tumor burden change, % in patients with PR or SD | 1.1 ± 7.1 | -10.7 ± 19.5 | 0.091 | -7.0 (-23.9-8.6) | 0.0 (-7.7-10.0) | 0.366 |

| Dose reduction | 10 (40.0) | 18 (72.0) | 0.022a | 7 (70.0) | 9 (90.0) | 0.288 |

| Delivery dose | 89.6 ± 12.4 | 84.4 ± 15.3 | 0.196 | 81.9 (73.1-93.4) | 67.7 (64.6-84.6) | 0.218 |

| Total over 80% dose | 17 (68.0) | 15 (60.0) | 0.565 | 6 (60.0) | 4 (40.0) | 0.398 |

| Chemotherapy days | 56.0 (29.7-82.3) | 112.0 (43.5-180.5) | 0.001a | 98.0 (0.0-206.5) | 112.0 (27.0-197.0) | 0.790 |

| Progression-free survival | 62.0 (55.3-125.4) | 206.0 (158.1-300.5) | 0.000a | 147.0 (86.4-263.0) | 174.0 (94.6-270.4) | 0.796 |

| Overall survival | 102.0 (75.6-155.1) | 302.0 (215.9-388.4) | 0.000a | 227.0 (108.9-342.1) | 211.0 (125.3-314.3) | 0.739 |

| 2nd chemotherapy | 3 (12.0) | 12 (48.0) | 0.005a | 1 (10.0) | 3 (30.0) | 0.288 |

| TS-1 | 1 (4.0) | 6 (24.0) | 1 (10.0) | 2 (20.0) | ||

| Gemcitabine mono | 0 (0.0) | 4 (16.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (10.0) | ||

| GA | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| FOLFIRINOX | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Onivyde | 1 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| 5-FU base | 1 (4.0) | 1 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| 2nd chemotherapy PFS in d | 86.0 (23.7-125.6) | 83.0 (45.5-123.4) | 0.572 | 75 (N/A) | 74 (-17.5-136.9) | 0.999 |

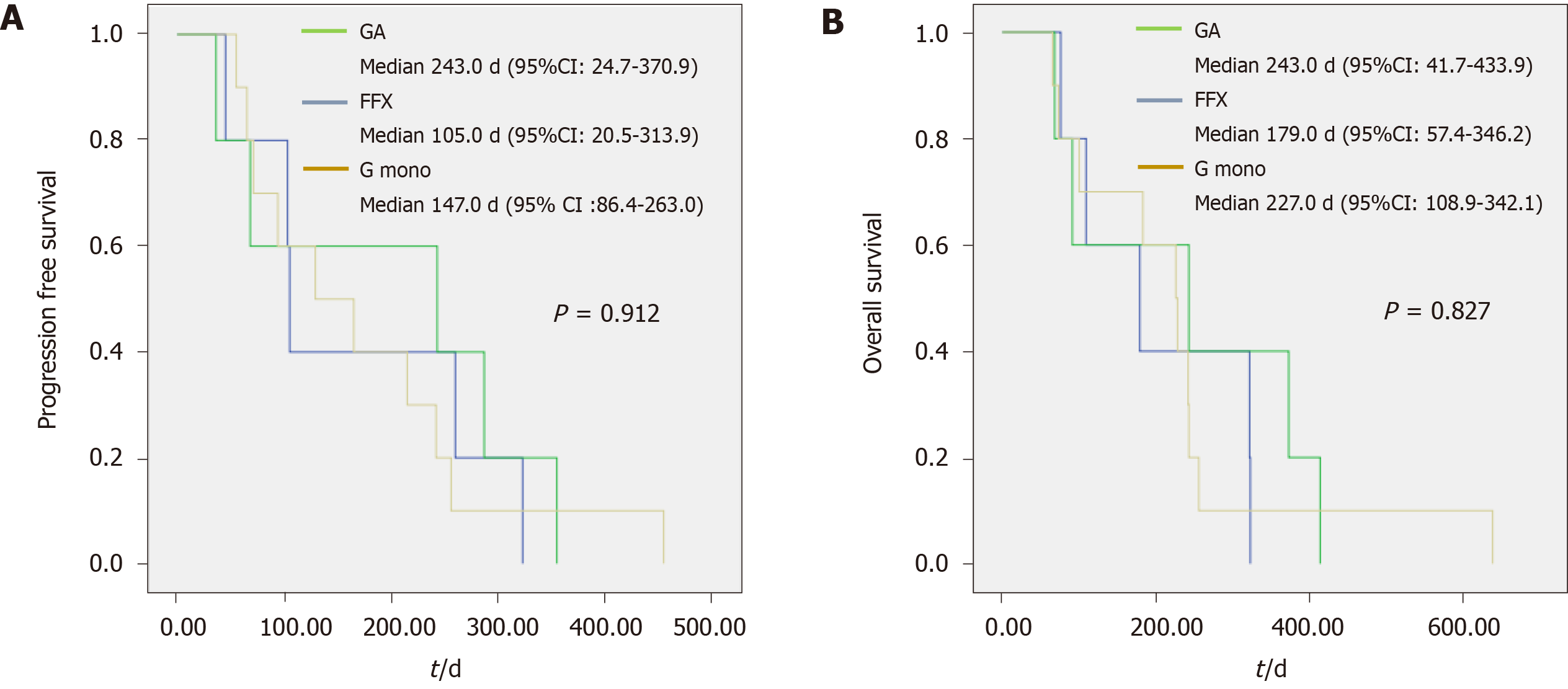

In the very elderly group, there was no significant difference between the G mono and combination chemotherapy groups in the disease control rate (60% and 80%, respectively, P = 0.355), PFS [147.0 (86.4–263.0) and 174.0 (94.6–270.4) d, respectively, P = 0.796], and OS [227.0 (108.9–342.1) and 211.0 (125.3–314.3) d, respectively, P = 0.739]. Regarding the proportion of tumor burden change before and after chemotherapy, the difference between the two chemotherapy groups was smaller than that in the elderly group [7.0% (-9.1–39.7) and 3.5% (-5.9–13.4), respectively, P = 0.633]. The actual delivery dose compared to the expected dose [81.9% (73.1–93.4) and 67.7% (64.6–84.6), respectively, P = 0.218] was lower in the combination chemotherapy group; however, the difference was not statistically significant. Figure 2 shows the median PFS (G mono, GA, and FFX; 147, 243, and 105 d, respectively, P = 0.912) and median OS (227, 243, and 179 d, respectively, P = 0.827) for each regimen in the very elderly group.

Adverse events associated with each chemotherapy regimen are listed in Table 4. Thromboembolism (G mono vs GA vs FFX; 8.9% vs 5.9% vs 28.0%, P = 0.041), neuropathy (0.0% vs 61.8% vs 28.0%, P = 0.006), and neutropenia (40.0% vs 76.5% vs 84.0%, P = 0.000) were significantly different between the two chemotherapy groups. Although there was no statistical difference, the rates of adverse events of admission (G mono, GA, and FFX; 28.9%, 32.4%, and 40.0%, respectively, P = 0.359), fatigue (48.9%, 64.7%, and 64.0%, respectively, P = 0.245), and diarrhea (17.8%, 20.6%, and 32.0%, respectively, P = 0.065) were lower in the G mono group than in the combination chemotherapy group. Adverse events associated with each age group are listed in Table 5. Neutropenia (36.0% vs 77.6% in the elderly, P = 0.000) (45.0% vs 90.0% in the very elderly, P = 0.038) and neuropathy (0.0% vs 46.9% in the elderly, P = 0.000) (0.0% vs 50.0% in the very elderly, P = 0.001) were significantly different between the two chemotherapy group in the elderly and very elderly groups.

| Adverse events | Gemcitabine mono, n = 45 | GA, n = 34 | FOLFIRINOX, n = 25 | P value |

| Admission | 13 (28.9) | 11 (32.4) | 10 (40.0) | 0.359 |

| Thromboembolism | 4 (8.9) | 2 (5.9) | 7 (28.0) | 0.041a |

| Neuropathy (Grade 1,2/3,4) | 0 (0.0) (0/0) | 21 (61.8) (7/14) | 7 (28.0) (6/1) | 0.006a |

| Neutropenia (Grade 1,2/3,4) | 18 (40.0) (9/9) | 26 (76.5) (9/17) | 21 (84.0) (7/14) | 0.000a |

| Thrombocytopenia (Grade 1,2/3,4) | 24 (53.3) (14/10) | 16 (47.0) (10/6) | 7 (28.0) (1/6) | 0.241 |

| Nausea (Grade 1,2/3,4) | 12 (26.6) (11/1) | 7 (21.6) (5/2) | 9 (36.0) (7/2) | 0.344 |

| Fatigue (Grade 1,2/3,4) | 22 (48.9) (12/10) | 24 (64.7) (12/10) | 16 (64.0) (9/7) | 0.245 |

| Diarrhea (Grade 1,2/3,4) | 8 (17.8) (7/1) | 7 (20.6) (5/2) | 8 (32.0) (4/4) | 0.065 |

| Colitis/pneumonia | 9 (20.0) (2/7) | 7 (20.5) (1/6) | 6 (24.0) (3/3) | 0.959 |

| Adverse events | Gemcitabine mono, n = 45 | GA & FOLFIRINOX, n = 59 | P value | |||

| Elderly, n = 25 | Very elderly, n = 20 | Elderly, n = 49 | Very elderly, n = 10 | Elderly | Very elderly | |

| Admission | 13 (28.9) | 21 (35.6) | 0.475 | |||

| 6 (24.0) | 7 (35.0) | 18 (36.7) | 3 (30.0) | 0.275 | 0.793 | |

| Thromboembolism | 4 (8.9) | 9 (15.3) | 0.336 | |||

| 2 (8.0) | 2 (10.0) | 7 (14.3) | 2 (20.0) | 0.441 | 0.465 | |

| Neuropathy (Grade 1,2/3,4) | 0 (0.0) | 28 (47.5) | 0.000* | |||

| (0/0) | (13/15) | |||||

| 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 23 (46.9) | 5 (50.0) | 0.000* | 0.001a | |

| (0/0) | (0/0) | (9/14) | (4/1) | |||

| Neutropenia (Grade 1,2/3,4) | 18 (40.0) | 47 (79.7) | 0.000* | |||

| (9/9) | (16/31) | |||||

| 9 (36.0) | 9 (45.0) | 38 (77.6) | 9 (90.0) | 0.000* | 0.038a | |

| (4/5) | (5/4) | (11/27) | (5/4) | |||

| Thrombocytopenia (Grade 1,2/3,4) | 24 (53.3) | 23 (39.0) | 0.312 | |||

| (14/10) | (11/12) | |||||

| 12 (48.0) (8/4) | 12 (60.0) (6/6) | 19 (38.8) (9/10) | 4 (40.0) (2/2) | 0.806 | 0.370 | |

| Nausea (Grade 1,2/3,4) | 12 (26.6) | 16 (27.1) | 0.655 | |||

| (11/1) | (12/4) | |||||

| 5 (20.0) | 7 (35.0) | 14 (28.6) | 2 (20.0) | 0.236 | 0.354 | |

| (5/0) | (6/1) | (10/4) | (2/0) | |||

| Fatigue (Grade 1,2/3,4) | 22 (48.9) | 38 (64.4) | 0.171 | |||

| (12/10) | (21/17) | |||||

| 11 (44.0) | 11 (55.0) | 32 (65.3) | 6 (60.0) | 0.101 | 0.669 | |

| (7/4) | (5/6) | (19/13) | (2/4) | |||

| Diarrhea (Grade 1,2/3,4) | 8 (17.8) | 15 (25.4) | 0.180 | |||

| (7/1) | (9/6) | |||||

| 5 (20.0) | 3 (15.0) | 12 (24.5) | 3 (30.0) | 0.635 | 0.074 | |

| (4/1) | (3/0) | (9/3) | (0/3) | |||

| Colitis/pneumonia | 9 (20.0) | 13 (22.0) | 0.906 | |||

| (2/7) | (4/9) | |||||

| 3 (12.0) | 6 (30.0) | 12 (24.5) | 1 (10.0) | 0.205 | 0.134 | |

| (1/2) | (1/5) | (3/9) | (1/0) | |||

In this study, we evaluated the efficacy of G mono and combination chemotherapy in elderly and very elderly groups. In the elderly group, the median PFS and OS were significantly longer for combination chemotherapy than for G mono. In the G mono group in elderly patients, more people died within 2 mo compared to the combination group (32% vs 4%, P = 0.009), and most of them died from cancer progression. Due to this phenomenon, chemotherapy days, PFS, and OS are considered to be shorter in this group than in the combination group. Moreover, combination chemotherapy had a significantly more pronounced effect on tumor burden before and after chemotherapy. However, G mono had similar efficacy to that of combination chemotherapy in the very elderly group. Furthermore, the rate of severe adverse events was significantly lower in the G mono group than in the combination chemotherapy group.

Some studies, including meta-analyses, have been conducted on chemotherapy for patients aged 65 years and older[8,11]. These studies showed that combination chemotherapy was more effective than G mono. In addition, the importance of improving tolerability through appropriate dose reduction of combination therapy in older patients is suggested. Appropriate dose reduction can improve tolerability while maintaining efficacy; however, excessive dose reduction would negatively affect the efficacy. Furthermore, most of the previous studies focused on patients older than 65 years and not on very elderly patients older than 75 years. One Japanese study[12] demonstrated the efficacy of the GA regimen in patients older than 75 years; they suggested that the GA regimen is feasible with appropriate dose reductions provided treatment-related decisions are managed appropriately. However, in the study, only 48% of patients completed two cycles of the GA regimen. The remaining patients did not tolerate two cycles of chemotherapy, despite appropriate dose adjustments. In our study, the median delivery dose in the very elderly group was 67.7% in the combination chemotherapy group and 81.9% in the G mono group. Active dose reduction was required in the combination chemotherapy group, and the effect of chemotherapy was attenuated in the very elderly patients. Moreover, the effect on tumor burden was decreased with dose reductions in very elderly patients. We consider that this difference in dose delivery contributed to the similar efficacies of combination chemotherapy and G mono in the very elderly patients in our study, especially regarding PFS and OS.

When comparing the clinical outcomes of elderly and very elderly patients, there are big differences in prognostic factors from baseline characteristic differences. Several factors are known to be associated with prognosis in pancreatic cancer such as the neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio, CA19-9 level, ECOG performance status, and tumor burden[13-16]. ECOG performance status cannot be used as a prognostic factor in patients undergoing G mono because G mono is mainly used for patients with poor performance status. When comparing the efficacy of chemotherapy, there should be no differences in these prognostic factors; thus, we performed a propensity score matching to eliminate any differences. Differences between each chemotherapy group in patients in the same age group could be corrected; however, due to a lack of sufficient patient numbers, differences between the elderly and very elderly patients in each chemotherapy group could not be corrected. After propensity score matching, differences between the elderly and very elderly patients in the G mono group were bigger regarding CA19-9, tumor burden, and neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio. We consider that these differences resulted in the disparate prognoses of the elderly and very elderly patients.

There were no significant differences in the rates of adverse events between the G mono and combination chemotherapy groups in both the elderly and very elderly patients. Because G mono resulted in few adverse events even in the very elderly patients, it was possible to maintain treatment with only appropriate dose reductions. Thromboembolism, neuropathy, and neutropenia occurred at significantly lower rates in the G mono group compared to the combination chemotherapy group. Specifically, the incidence of neutropenia, the most common adverse event in the G mono group, was half that in the GA and FFX regimens. A prospective study[17] showed that older patients with poor performance status had more severe adverse events. If patients with a similar performance status received each regimen, G mono could result in a lower rate of adverse events than the combination regimens indicating that it would be a superior option in very elderly patients.

Our study has several limitations. First, this was a single center study with a retrospective design that enrolled a relatively limited number of patients, especially very elderly patients. Second, as the number of enrolled patients was relatively small, propensity score matching resulted in patients with large delta values. Therefore, the baseline characteristics were somewhat different, although the difference was not statistically significant. Further, disease progression could not be accurately identified in about 10%–20% of patients because of loss to follow-up, death before disease progression, or maintenance of the efficacy of chemotherapy until evaluation day.

In conclusion, in elderly patients, combination therapy was more effective compared to G mono. However, G mono may be superior for managing metastatic pancreatic cancer in very elderly patients compared to combination therapy in terms of adverse events. Further studies are needed to determine which regimen works better in very elderly patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer.

In very elderly (age 75 and over) pancreatic cancer patients, it is not well known which chemotherapy regimens are more effective.

It is hypothesized that a chemotherapy regimen that has low adverse event rates may be more effective in very elderly patients.

In this study, the authors aimed to determine which chemotherapy regimen is more efficacious in very elderly pancreatic cancer patients.

The authors performed analysis after propensity-score matching to compare the patients who received combination or gemcitabine monotherapy chemotherapy.

In very elderly patients, there was no significant difference in progression-free survival and overall survival between the gemcitabine monotherapy and combination chemotherapy groups.

Gemcitabine monotherapy may be a better option to manage metastatic pancreatic cancer in very elderly patients.

In very elderly patients, chemotherapy regimens have similar efficacy, so it seems reasonable to use gemcitabine treatment in terms of adverse effects.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D, D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kimura Y, Kozarek R, Matsuo Y, Sahu RP S-Editor: Wang DM L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12667] [Cited by in RCA: 15314] [Article Influence: 3062.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Gawron AJ, Gapstur SM, Fought AJ, Talamonti MS, Skinner HG. Sociodemographic and tumor characteristics associated with pancreatic cancer surgery in the United States. J Surg Oncol. 2008;97:578-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Baxter NN, Whitson BA, Tuttle TM. Trends in the treatment and outcome of pancreatic cancer in the United States. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:1320-1326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sohal DP, Mangu PB, Khorana AA, Shah MA, Philip PA, O'Reilly EM, Uronis HE, Ramanathan RK, Crane CH, Engebretson A, Ruggiero JT, Copur MS, Lau M, Urba S, Laheru D. Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2784-2796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 248] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouché O, Guimbaud R, Bécouarn Y, Adenis A, Raoul JL, Gourgou-Bourgade S, de la Fouchardière C, Bennouna J, Bachet JB, Khemissa-Akouz F, Péré-Vergé D, Delbaldo C, Assenat E, Chauffert B, Michel P, Montoto-Grillot C, Ducreux M; Groupe Tumeurs Digestives of Unicancer; PRODIGE Intergroup. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1817-1825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4838] [Cited by in RCA: 5640] [Article Influence: 402.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, Chiorean EG, Infante J, Moore M, Seay T, Tjulandin SA, Ma WW, Saleh MN, Harris M, Reni M, Dowden S, Laheru D, Bahary N, Ramanathan RK, Tabernero J, Hidalgo M, Goldstein D, Van Cutsem E, Wei X, Iglesias J, Renschler MF. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1691-1703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4035] [Cited by in RCA: 4889] [Article Influence: 407.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Burris HA, Moore MJ, Andersen J, Green MR, Rothenberg ML, Modiano MR, Cripps MC, Portenoy RK, Storniolo AM, Tarassoff P, Nelson R, Dorr FA, Stephens CD, Von Hoff DD. Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2403-2413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4351] [Cited by in RCA: 4179] [Article Influence: 149.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jin J, Teng C, Li T. Combination therapy versus gemcitabine monotherapy in the treatment of elderly pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2018;12:475-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ouchi Y, Rakugi H, Arai H, Akishita M, Ito H, Toba K, Kai I; Joint Committee of Japan Gerontological Society (JGLS) and Japan Geriatrics Society (JGS) on the definition and classification of the elderly. Redefining the elderly as aged 75 years and older: Proposal from the Joint Committee of Japan Gerontological Society and the Japan Geriatrics Society. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17:1045-1047. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 349] [Article Influence: 43.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Karasek P, Skacel T, Kocakova I, Bednarik O, Petruzelka L, Melichar B, Bustova I, Spurny V, Trason T. Gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: a prospective observational study. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2003;4:581-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Garcia G, Odaimi M. Systemic Combination Chemotherapy in Elderly Pancreatic Cancer: a Review. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2017;48:121-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hasegawa R, Okuwaki K, Kida M, Yamauchi H, Kawaguchi Y, Matsumoto T, Kaneko T, Miyata E, Uehara K, Iwai T, Watanabe M, Kurosu T, Imaizumi H, Ohno T, Koizumi W. A clinical trial to assess the feasibility and efficacy of nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine for elderly patients with unresectable advanced pancreatic cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2019;24:1574-1581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kim HJ, Lee SY, Kim DS, Kang EJ, Kim JS, Choi YJ, Oh SC, Seo JH, Kim JS. Inflammatory markers as prognostic indicators in pancreatic cancer patients who underwent gemcitabine-based palliative chemotherapy. Korean J Intern Med. 2020;35:171-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ballehaninna UK, Chamberlain RS. Serum CA 19-9 as a Biomarker for Pancreatic Cancer-A Comprehensive Review. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2011;2:88-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sørensen JB, Klee M, Palshof T, Hansen HH. Performance status assessment in cancer patients. An inter-observer variability study. Br J Cancer. 1993;67:773-775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 298] [Cited by in RCA: 339] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kunzmann V, Ramanathan RK, Goldstein D, Liu H, Ferrara S, Lu B, Renschler MF, Von Hoff DD. Tumor Reduction in Primary and Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer Lesions With nab-Paclitaxel and Gemcitabine: An Exploratory Analysis From a Phase 3 Study. Pancreas. 2017;46:203-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Phaibulvatanapong E, Srinonprasert V, Ithimakin S. Risk Factors for Chemotherapy-Related Toxicity and Adverse Events in Elderly Thai Cancer Patients: A Prospective Study. Oncology. 2018;94:149-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |